EIGHT

HENRY V

The Quest for Exemplarity

APRIL 23, USUALLY DESCRIBED AS “Shakespeare’s birthday,” was also recorded as the date of his death. Either this is an uncanny coincidence—and such things do happen—or we are again in the world of Shakespeare-larger-than-life, the Shakespeare who has already become a myth. Since Thomas Jefferson and John Adams both died on the same day, July 4, 1826, the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, perhaps we may rest happy here with the idea that coincidence rules. But in any case, it is another striking coincidence that April 23 is, and was in Shakespeare’s time, also known as St. George’s Day.

St. George is the patron saint of England, and from the fifteenth through the eighteenth centuries his feast day was celebrated on a par with Christmas. That Shakespeare’s birthday (and death day) is also the feast day of the patron saint of England may again suggest either uncanny coincidence at work, and/or the operations of early Bardolatry.

St. George as patron of England also plays a part—at least a rhetorical part—in Shakespeare’s play Henry V. At the close of his affecting and effective speech to rally the troops, “Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more, / Or close the wall up with our English dead” (3.1.1–2), King Henry urges all those in the battle, the noblemen and the yeomen, to move forward:

The game’s afoot.

Follow your spirit, and upon this charge

Cry, “God for Harry! England and Saint George!”

3.1.32–34

By the very next scene the rallying cry has already been made into a slogan, as Bardolph enters with his disreputable colleagues, crying, “On, on, on, on, on! To the breach, to the breach!” (3.2.1)—and trying to escape the battle. In a phenomenon familiar to anyone who follows modern political rhetoric in a time of 24/7 news cycles, words are here taken out of context, cited, recited, and converted into a catchphrase for the speaker’s own purposes. From “Nixon’s the one” to “Where’s the beef?” to “Yes, we can!” such phrases, consumer-and battle-tested, have been used to mobilize armies of voters in the era of the “selling” of presidents. But such slogans have always functioned in this floating fashion, coming to mean whatever the new context offers. King Henry’s mention of “Saint George!” (designed in this ending couplet to rhyme with “charge”) has the effect of raising the emotional war effort beyond the immediate moment (“Ask not what your country can do for you…”). At the same time, linking the three names (Harry, England, St. George) identifies and personifies them: for the moment of the battle the King becomes Saint George. Does the April 23 birthdate similarly identify and personify “Shakespeare” as “England”?

Raffaello Sanzio, St. George Fighting the Dragon

Henry V is the fourth play in a series, the so-called second tetralogy, or second group of four history plays, that Shakespeare wrote and brought to the stage. Richard III, the culminating play in the first group of four English history plays, is a play that brings “history” relatively close in time to Shakespeare’s own day: Henry VII, who defeated Richard III, was Queen Elizabeth’s grandfather. Shakespeare wrote the plays about a more recent time earlier in his career than the plays set in a more distant England: the years covered by the second tetralogy, from Richard II (who was king during the time of Chaucer) to Henry V (born in 1387, crowned in 1413, died in 1422), is squarely within the medieval period. The most salient “real world” fact about the Battle of Agincourt, for which the historical King Henry V is best remembered, is that it featured a relatively new kind of weaponry, the medieval (or “Welsh”) longbow, sometimes described as “the machine gun of the Middle Ages.” A skilled longbow archer could shoot around twenty aimed arrows a minute. Two modern films of Shakespeare’s Henry V—the one with Laurence Olivier (1944, in the middle of World War II) and the one with Kenneth Branagh (1989, responding to the British engagement in the far less popularly supported Falklands War)—show the devastation this “humble” weapon was able to produce when arrayed against serried ranks of horsemen in armor and carrying pennants, spears, and other cumbersome regalia of war.

Laurence Olivier in The Chronicle History of King Henry the Fift with His Battell Fought at Agincourt in France (1944)

Kenneth Branagh in Henry V (1989)

What does it mean for us to consider this one play on its own, without the context of the preceding three? I should note that in modern theater and cinema this is often done; the plays are almost always independently produced, staged, filmed, taught, and discussed. A classic film combining Henry IV, parts 1 and 2, and a staged “unscene” from Henry V (the death of Falstaff) was made by Orson Welles in 1965, and entitled—after a phrase from Henry IV, Part 2—Chimes at Midnight (Welles, of course, played Falstaff). Although Henry V may be read in part as a repetition and recuperation of the first play in the series, Richard II, and although there have been some marathon stagings of the four plays together—and, indeed, of the four plays of the first tetralogy together—these plays, as plays, are designed to be freestanding and to give you all the information about character, history, and plot that you need to understand and interpret what is going on. And unlike the other plays in the series, which are much admired, much performed, and much quoted, but usually in the context of “Shakespeare,” this play, Henry V, has attained a double afterlife for modern culture: both in the annals of patriotic rhetoric and warfare, and in the peculiar and lucrative world of the business school, the realm of motivational speaking, and the leadership institute. As we will see, King Henry has been presented as an example of what might be called best practices for corporate executives in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

The play begins with an actor designated as the Chorus, who speaks at the beginning of each act, and also speaks an epilogue at the end of the play. The first prologue spoken by the Chorus, at the start of Henry V, has become one of the most famous speeches in Shakespeare, because it describes the theater, the (supposed) limitations of the actors, the stage, and the playwright, and the active, imaginative nature of the theater audience. As we have already seen, the Chorus’s lines are so recognizable as Shakespeare that Barbara Garson was able to riff on them at the beginning of her political parody MacBird. This is a long passage, but it is worth quoting in its entirety, because the effect is cumulative, and the logic—both rhetorical and theatrical—something akin to magic. The movement from “O for” to “But” to “Suppose,” “Piece out,” and “Think” transfers the agency of the stage from the actor (and the playwright) to the audience.

O for a muse of fire, that would ascend

The brightest heaven of invention:

A kingdom for a stage, princes to act,

And monarchs to behold the swelling scene.

Then should the warlike Harry, like himself,

Assume the port of Mars, and at his heels,

Leashed in like hounds, should famine, sword, and fire

Crouch for employment. But pardon, gentles all,

The flat unraisèd spirits that hath dared

On this unworthy scaffold to bring forth

So great an object. Can this cock-pit hold

The vasty fields of France? Or may we cram

Within this wooden O the very casques

That did affright the air at Agincourt?

O pardon: since a crookèd figure may

Attest in little place a million,

And let us, ciphers to this great account,

On your imaginary forces work.

Suppose within the girdle of these walls

Are now confined two might monarchies,

Whose high uprearèd and abutting fronts

The perilous narrow ocean parts asunder.

Piece out our imperfections with your thoughts:

Into a thousand parts divide one man,

And make imaginary puissance.

Think, when we talk of horses, that you see them,

Printing their proud hoofs i’th’ receiving earth;

For ’tis your thoughts that now must deck our kings,

Carry them here and there, jumping o’er times,

Turning th’ accomplishments of many years

Into an hourglass—for the which supply,

Admit me Chorus to this history,

Who Prologue-like your humble patience pray

Gently to hear, kindly to judge, our play.

Prologue 1–34

The Olivier film of 1944 famously began with an eagle’s-eye view of the stage, gradually moving in closer, and providing a visual counterpart to the description of the “wooden O” that has become a proverbial description of Shakespeare’s stage. Most theaters at this time were polyhedrons. This play may first have been performed at the Curtain, but its true home was the new public theater Shakespeare’s company had built on the bankside of the Thames, the Globe, where most of his plays were then performed. (The Tempest, a play that we have seen to be full of magical devices, was performed at a smaller indoor theater, the Blackfriars, allowing for more in the way of artifice and lighting effects.) So the Chorus’s prologue is a glimpse at the theater and backstage. This was mirrored at the end, when the grand sweep of filmic “realism” returned to the stage and to actors on it.

Kenneth Branagh, always competitive with his great (and admired) predecessor, Laurence Olivier, shot his version of the Chorus’s Prologue not on a simulacrum of a stage but on a film set, with the Chorus, played by Derek Jacobi, in street wear (of a rather “theatrical” kind, overcoat and scarf), wandering through the empty studio. Again, the effect—already insisted upon in Shakespeare’s language—was to give the audience a kind of double vision: a vision into the past (underscored in the Olivier film by a constant recourse to costumes and sets drawn from a medieval book of hours) and a vision of the supposed “present.”

SO THE ISSUES ABOUT “what is real” and “what is now” are deliberately put in question. But look at the language of the speech, which is even more definitive and suggestive than the film images. The Chorus begins by wishing, or rather, pretending to wish for, a kind of hyper–stage realism—princes would act princes, monarchs would be watching, the stage would be a kingdom, the king (the warlike Harry) would appear as himself, and then take on the mythological costume of the god of war, Mars. But. But. Instead, the Chorus points out, we have actors (“flat unraisèd spirits”), a stage (“this unworthy scaffold”). No theater can hold real armies, or “the vasty fields of France.”

This is a version of what in poetry is called an “inexpressibility topos” (for example, “No one could tell how many came to the feast…”). The teller is telling by not telling. And in the Prologue to Henry V the deficit is made a plus. Since we can’t see these things, we need to use our imaginations.

O pardon: since a crookèd figure may

Attest in little place a million,

And let us, ciphers to this great account,

On your imaginary forces work.

Prologue 15–19

A zero with an ordinal number in front of it may have great value. The players, as “ciphers” (zeroes) may be enhanced by the audience, which is given a crucial role:

Piece out our imperfections with your thoughts:

Into a thousand parts divide one man,

And make imaginary puissance.

Think, when we talk of horses, that you see them.

Prologue 23–26

The “hourglass” image makes it clear that time is being compressed—“your thoughts…must deck our kings.”

Every act of the play begins with this resituating of the action in the realm of the fictive and the imaginary. This is in part done in order to cover great stretches of time and history, explaining characters, their backgrounds, a shift of scene. But it is also both an old and a “modernist” device, destabilizing the realism of the front plane. The more “human” the characters seem—the frightened soldiers, the indomitable Welsh captain Fluellen, the thinking king—the more disconcerting it is to be pulled back into a narrative frame in which the fictionality and impermanence of what we are watching are emphasized.

Thus with imagined wing our swift scene flies

In motion of no less celerity

Than that of thought.

3.0.1–3

Begins the chorus to act 3,

Suppose that you have seen

The well-appointed king at Dover pier

3.0.3–4

Play with your fancies, and in them behold

Upon the hempen tackle ship-boys climbing;

3.0.7–8

O do but think

You stand upon the rivage

3.0.13–14

Grapple your minds to sternage of this navy.

3.0.18

Similar language of supposing, imagining, and thinking dominates every one of these Chorus speeches. “Now entertain conjecture of a time,” the Chorus begins act 4, and ends, “Yet sit and see, / Minding true things by what their mock’ries be.” And this impermanence, this exchange of state between true things and mockeries, becomes thematic as well as formal at the end of the play, when, after the victory at Agincourt, the peace with the French, the dynastic courtship transformed into a love match with Kate (Catherine) of France, and the promise that “English may as French, French Englishmen, / Receive each other” (5.2.39–40), the entire play is unraveled by the sobering words of the epilogue. For no sooner has the king spoken his final words,

Then shall I swear to Kate, and you to me,

And may our oaths well kept and prosp’rous be

5.2.345–46

than his place is taken onstage by the Chorus, who speaks a sonnet that undoes everything we (think we) have seen.

Thus far with rough and all-unable pen

Our bending author hath pursued the story,

In little room confining mighty men,

Mangling by starts the full course of their glory.

Small time, but in that small most greatly lived

This star of England. Fortune made his sword,

By which the world’s best garden he achieved,

And of it left his son imperial lord.

Henry the Sixth, in infant bands crowned king

Of France and England, did this king succeed,

Whose state so many had the managing

That they lost France and made his England bleed,

Which oft our stage hath shown—and, for their sake,

In your fair minds let this acceptance take.

Epilogue 1–14

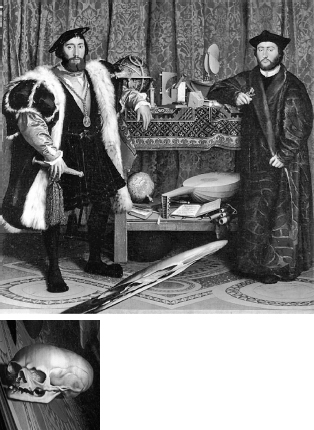

This is postmodernity before modernism—a description of historical events as “always already,” both imminent and belated—and it is highly characteristic of the English Renaissance. A fitting example from the early modern period is Hans Holbein’s famous portrait The Ambassadors (1533). Men of substance, surrounded by images of permanence and power, are depicted as standing on a patterned floor that, viewed from an oblique angle, resolves itself into a human skull. Like the much later rabbit-duck anamorphism of Gestalt psychology, the painting contains both images, but only one can be seen at a time. This device allows for the presentation of two conflicting views at once, and for discrepant awareness and dramatic irony. All is vanity. Dust thou art. The viewer or audience sees what the protagonists do not.

Hans Holbein, The Ambassadors and detail of the foreground skull, undistorted when viewed from an angle

So this play about victory and maturity is also about instability and impermanence, its formal nature deliberately at war with its heroic content. For a small and comic example of this, consider the way the English language continually deconstructs itself in the mouths of the French-speaking princess and her waiting woman in act 3, scene 4, turning apparently harmless phrases into dirty words. Words like “foot” and “cown” (for “gown”) are (mis) understood by the Princess as “mots de son mauvais, corruptible, gros, et impudique” (evil-sounding words, easily misconstrued, vulgar, and immodest) (3.4.447–48). The four-letter English cognates for foot and cown would have been readily, and comically, heard by the audience in the theater, whether or not those audience members understood French. The larger thematic point is as striking as the topical comedy: language is treacherous, meanings shift, all speech is dangerous and not always under the control of the speaker. This insistent instability of meaning is in fact characteristic of the theme of language and languages throughout the play.

COMPARISON OF THE Olivier and Branagh films makes clear the wide range of “meanings” that can be attached to scenes, characters, settings, and speeches, depending upon the context and the historical moment.

As we have already noted, the “war” surround of the two films was very different. Olivier had delivered the Crispin Crispian speech as a World War II pep talk on the national radio, and it was clearly associated with Britain’s sense of itself as a threatened smaller power in danger of being overwhelmed by the juggernaut of Nazi Germany. By the time Branagh remade the film, following, once again, in Olivier’s path, the situation was quite different. Britain was the major power, and the aggressor. War was less heroic and muddier (in all senses). (In a later battle scene, the king walks through the devastation of mud, corpses, and disorder everywhere.)

Reviewing Olivier’s film for Time magazine in 1946, James Agee observed that “the man who made this movie made it midway in England’s most terrible war, within the shadows of Dunkirk.” The soldiers with whom Henry talks on the eve of battle “might just as well be soldiers of World War II,” Agee remarked, adding that “no film of that war has yet said what they say so honestly or so well.”1 Olivier took a speech originally assigned, by Shakespeare, to “a cynical soldier” (“But if the cause be not good…” [4.1.128ff.]) and put it “in the mouth of a slow-minded country boy” with a “peasant patience” and the accents of Devon in his voice. Olivier had been given leave by the Royal Navy in 1942 to make a romantic comedy called Demi-Paradise (also known as Adventure for Two) about a Russian inventor in England “in the interest of Anglo-Russian relations,” and the navy then extended his leave so he could make Henry V, as Olivier quipped, “in the interest of Anglo-British relations.”2 (The title of Demi-Paradise is a reference to John of Gaunt’s famous “this England” speech in Shakespeare’s Richard II.)

Branagh’s Henry V, too, was underwritten by a government subsidy. A distinguished professor of French, recalling that in his childhood Agincourt was viewed as a “perfidious” act perpetrated by the English against the “gallant French knights,” wrote to The New York Times to speculate on why “the BBC and the British government” would give financial support to the film. “Could it be that Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s crumbling popularity needs Shakespeare to come to her rescue? With England in the wake of the Falklands crusade, and in a precarious position in the European community, anticipating the fateful union of Europe in 1992, is this a disguised effort to bolster British spirits?”3 Others, predictably, disagreed that the film was good press for Britain. Branagh had restored several unflattering scenes cut by Olivier from his patriotic film, like the king’s threat to the governor of Harfleur predicting rape and infanticide, the disgrace of three of Henry’s former friends from the Henry IV plays, now exposed as guilty of conspiracy and treason, and the hanging of his friend Bardolph for robbing a church.

One critic thought that Branagh had made “a young male-rite-of-passage movie” in the tradition of U.S. Vietnam films, rather than “a critique of institutional power and class injustice,” as the critic would have preferred, and thus was complicit in “whitewashing traditional autocracy and the logic of imperialism” while at the same time “giving us a Shakespeare that is genuinely popular, intelligent and enthralling, unforgettable if also unfaithful” to the details of the play.4 Branagh himself said that “all the blood-and-guts was quite deliberate. In fact, if eyewitness accounts of the Battle of Agincourt are to be believed, we were rather modest in our representation of it. It was very unpleasant, undignified, inelegant butchery.”5 The battle scenes were, nonetheless, handled with a certain cinematographic sentimentality. Shakespeare’s Henry had requested, after the battle, that the hymns Non nobis and Te Deum be sung in praise to God for the victory (4.8.117). Branagh envisages “the greatest tracking shot in the world,” while “to the accompaniment of a single voice starting the Non nobis hymn, the exhausted monarch would march the entire length of the battlefield to clear the place of the dead.”6 Filmed in slow motion, in an homage to directors like Akira Kurosawa and Sam Peckinpah, the aftermath of the battle summoned images of all wars, all casualties and survivors. I saw it in the same week as another movie about heroic soldiers outnumbered and at a disadvantage, the American Civil War film Glory (1989), and was struck by the similarity between the two scenes of battlefield devastation and loss, from the swelling music to the heartsick leader.

IN ALMOST ANY VERSION OF THIS PLAY, however, whether onstage, on film, or excerpted as a stand-alone exhortation, it is the famous Crispin Crispian speech that remains the emotional high point of Henry V. This is the speech that has been appropriated, more than any other part of the play, for various players and plots in “modern culture” from politics to business, and it may be useful—as well as pleasurable—to revisit its language here. The speaker, of course, is King Henry, and his audience begins “small” (replying to his kinsman or “cousin” Warwick), and ends “big,” addressing the audience, history, and the future.

By Jove, I am not covetous for gold,

Nor care I who doth feed upon my cost;

It ernes me not if men my garments wear;

Such outward things dwell not in my desires.

But if it be a sin to covet honour

I am the most offending soul alive.

………………………………………………

We would not die in that man’s company

That fears his fellowship to die with us.

This day is called the Feast of Crispian.

He that outlives this day and comes safe home

Will stand a-tiptoe when this day is named

And rouse him at the name of Crispian.

He that shall see this day, and live t’old age

Will yearly on the vigil feast his neighbours

And say, “Tomorrow is Saint Crispian.”

Then will he strip his sleeve and show his scars,

And say, “These wounds I had on Crispin’s day.”

Old men forget; yet all shall be forgot,

But he’ll remember, with advantages,

What feats he did that day. Then shall our names,

Familiar in his mouth as household words—

Harry the King, Bedford and Exeter,

Warwick and Talbot, Salisbury and Gloucester—

Be in their flowing cups freshly remembered.

This story shall the good man teach his son;

And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be rememberèd,

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers.

For he today that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition.

And gentlemen in England now abed,

Shall think themselves accursed they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day.

4.3.24–67

Olivier, performing the speech for a 1944 audience, cut the lines “be he ne’r so vile, / This day shall gentle his condition.” Branagh, in 1989, restored them. Why might this be? The egalitarian language of the fighting forces during the Second World War in an era when class consciousness was still vivid throughout Britain might have made even the glancing thought of a common soldier as coming from a “vile” or low social “condition” anathema to national spirit and national rhetoric. By Branagh’s time, more than forty years later, these lines seemed merely “historical” and even quaint, not likely to be taken personally by any listener or social group. And Branagh himself, with his chunky body and his bouncy manner, seemed himself deliberately ordinary and classless, whereas the slim and elegant Olivier, distinguished though he might be in the film from the effete French, was clearly aristocratic and “noble” in his bearing. Branagh, in other words, was already “us” rather than “you” or “them,” even before the battle that would, by Henry’s redemptive rhetoric, transform the band of brothers, however “vile” their origins, into English gentlemen.

WHEN I WAS INVITED TO SPEAK to the Harvard College class of 1945—the war class—on the occasion of their sixtieth reunion, I began our discussion with the Crispin Crispian speech. The alumni, together with their spouses and partners, were a surprisingly large group, something between a hundred and two hundred people, graduates of coursework, battlefields, and three-quarters of a century of living, gathered on a Sunday morning to remember the past of the classroom, the past of the war and the ensuing histories. We noted on that occasion that the word “theater” itself marked the common ground of these endeavors. Since 1914, at least, when Winston Churchill used it to describe “the hand of war…in the Western Theatre,” that word, denoting a place of action, has been in frequent use to describe a region of the world in which war is being fought.7 What especially engaged these veterans was the idea that memories embellish the parts individuals played in the heroic conflict so long ago.

Old men forget; yet all shall be forgot,

But he’ll remember, with advantages,

What feats he did that day.

……………………………………

This story shall the good man teach his son;

And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be rememberèd.

Remembering “with advantages”—that is, with additions that make the story better—is, in fact, a good description of Shakespeare’s Henry V as a play: a heroic reconstitution of a messy moment from centuries previous, reflecting positively upon both the older time and the present one, or, as we have seen in the case of all history plays, on three time periods at once: the one depicted in the fiction, the time of the play’s original writing and performance, and the (shifting) present. So it was with the Greatest Generation—and so it has been with us.

A production by Michael Bogdanov in 1986 came after the Falklands experience, but it was Nicholas Hytner’s 2003 version at the Royal National Theatre of Great Britain that took in the full panoply of the post-9/11 world. Tanks and television screens dominated the stage, and Henry’s motives as commander in chief, leading his nation into war, were cast into serious doubt. “The play is a Rorschach test that can be made to fit a lot of political situations,” said one American theater director. “You can turn it into a jingoistic production that serves in times when courage and patriotism are needed, or you can choose, as Hytner did, to use it to question military adventures. The depth and complexity of the play is such that it can work either way.”8

But many modern appropriations of the play, in order to tell a political story, go directly from the text to its application, without the intervention of a stage or film performance. Numerous commentators saw the connection between Shakespeare’s Henry V and the war in Iraq. Political journalist Arianna Huffington wrote that Henry V “contains far more truth about our present situation than anything coming out of the White House or the Pentagon.”9 George W. Bush’s hard-drinking, hard-partying youth and his “conversion” seem directly to parallel the wild youth and reformation of Prince Hal; the tension with a strong paternal predecessor and namesake marks “George II” as a version of Henry V. The play’s opening scene, in which the clergy are brought on board to support the war, rings a familiar warning bell. Indeed, the old king’s advice to his son in Henry IV to “busy giddy minds / With foreign quarrels” (2 Henry IV 4.3.341–42) seemed as apt a description of the foreign policy of George W. Bush in Iraq and Afghanistan in the early years of the twenty-first century as it was—in the mind of the American historian Charles Beard—a description of “American interventionism and adventurism” in September 1939, when Beard published an article called “Giddy Minds and Foreign Quarrels” in the pages of Harper’s magazine.10

President George W. Bush walks the deck of the U.S.S. Abraham Lincoln

King Henry the national hero, King Henry the living incarnation of England’s Saint George, King Henry the adventurer, King Henry the opportunist, King Henry the cunning manipulator, King Henry the friend of corrupt politicians: none of these portrayals is inappropriate, and none disqualifies the others. In this context, there is no simple “truth,” no one right answer. In looking at the arc of the character in the past half century it is of interest to see how the pendulum has swung, from the self-evidently “heroic” Henry of World War II who could summon an outnumbered wartime Britain to sacrifice and greatness, to the present-day suspicion of King Henry’s motives and abilities when juxtaposed with American (mis) adventures in the Middle East. Depending upon your politics, it seems, you can find something to admire or something to deplore.

But as striking as has been this change in the fortunes of King Henry V, the one place he has remained almost unquestionably admirable is among those who regularly read—or appear in—Fortune magazine.

THE MANAGEMENT AND BUSINESS book industry—a booming business right now—garners much of its managerial “wisdom” from Shakespeare’s works, as we can see from a list of recent titles, including: Shakespeare in Charge: The Bard’s Guide to Leading and Succeeding on the Business Stage (1999); Shakespeare on Management (1999); Inspirational Leadership: Henry V and the Muse of Fire—Timeless Insights from Shakespeare’s Greatest Leader (2001); and Say It Like Shakespeare: How to Give a Speech Like Hamlet, Persuade Like Henry V, and Other Secrets from the World’s Greatest Communicator (2001). On the cover of this book the phrase “world’s greatest communicator” is in capital letters, and the cover image shows a man in a modern business suit, but with an Elizabethan ruff, a high forehead, and a pageboy hairdo, earnestly addressing a table of male and female executives, one of whom is transcribing his words on a laptop.

For the authors of these books, and for those who run “leadership institutes” in Washington, D.C., and around the country, Shakespeare provides object lessons in real-life management and crises, and for them Henry V is the great exemplar of “leadership.” Whole chapters are devoted to him, and whole sessions of the institutes focus on his example.

“Henry V is Shakespeare’s great heroic leader,” says Paul Corrigan in Shakespeare on Management. “Above all the lessons for managers from Shakespeare’s Henry concern his management of people. He listens to and talks with his troops in such a way as to motivate them to ever higher deeds of daring. This is a vital part of management.”11

Corrigan cautions that one should not look to Shakespeare for simple heroics about leadership. His message is hard: “Even if you reach the top, even if you defeat your enemies against the odds, even if you get the girl as well, there are very dark moments. And they are at the core of senior management. Power is not clean.”12 A key case in point is the hanging of Bardolph (a scene that, as we’ve noted, was omitted from the highly patriotic Olivier film and restored in the more ambivalent Branagh version). For Corrigan, the choice is a good lesson for managers. King Henry, you will recall, says about Bardolph and his crime, stealing from a church, “We would have all such offenders so cut off” (3.6.98). Here is Corrigan’s analysis:

On Henry’s orders a close friend is hanged, and for the purpose of the invasion necessarily so—the politics of an invading army compel it…. No modern managers are in the position to execute a friend. But many of us have had to make a decision in such a way as to forget some past personal relationship…. Shakespeare is teaching us a greater point on a wider field…. The execution of a friend makes a number of points with great clarity:

• If I am prepared to hang him, since you know he is my friend, then the rest of you had better behave.

• If I am prepared to hang him, since you know he is my friend, this an important principle.

• If I am prepared to hang him, then the army is doing something much more important than what we all normally think of as important, that is, friendship.13

Likewise, commenting on the famous speech at Agincourt, Corrigan explains that it illustrates “a point that every major management guru stresses again and again: your staff will make or break your enterprise and your capability as a manager.”14 He inspires “pride of workmanship” in his troops, which “means more to the production worker than gymnasiums, tennis courts and recreation areas.”15 His speech “successfully motivates his troops.”16 “This is a clear example of human resource management at its highest.”17

The long chapter on Henry V (the book contains others on less successful leaders, like Macbeth, Richard III, King Lear, and Coriolanus) is intercut with quotations from state-of-the-art books on business management, in cluding those by Tom Peters and Peter Drucker, two of the architects of the field.

Shakespeare—and especially Henry V—supply the “proof texts” for the argument about making managers. In the introduction, Corrigan quotes the glorious “Once more unto the breach” speech from act 3, scene 1 (which, as we have already had occasion to notice, was immediately turned into a political slogan by the opportunistic and mercenary Pistol in the next scene of Shakespeare’s play):

Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more,

Or close the wall up with our English dead.

……………………………………

On, on, you noblest English,

Whose blood is fet from fathers of war-proof.

……………………………………

For there is none of you so mean and base

That hath not noble lustre in your eyes.

I see you stand like greyhounds in the slips,

Straining upon the start. The game’s afoot.

Follow your spirit, and upon this charge

Cry, “God for Harry! England and Saint George!”

3.1.1–34

And he follows it immediately with this observation: “Why is it that nearly all the managers I know would like to deliver a speech like this to their staff? They want to make this speech, not because they want to be in a war, but because they would love to be as certain as Henry is that their people will follow them.”18 I should note that Corrigan’s book was published in 1999, before the Iraq War (and indeed before the terrorist attacks of 9/11). There are more than the usual set of ironically discrepant time periods here: Henry V’s actual dates (medieval); Shakespeare’s (early modern); management discourse of the late 1990s; and the (shifting) present day.

Former Reagan arms control director Kenneth Adelman and his wife, Carol, run a leadership training program wittily called Movers & Shakespeares. Here are some selections from their Web site:

Drawing on their extensive experience in top positions in government, public corporations, and non-profit groups, Carol and Ken Adelman work closely with companies and universities to customize each program to address the key issues facing their particular organization at the time.

The Adelmans select the most apt Shakespeare play to fit the program’s purpose. For leadership and ethics, they draw on Henry V, for change management, Taming of the Shrew, for risk management and diversity, Merchant of Venice, and for crisis management, Hamlet.

No prior knowledge of Shakespeare is required….

Participants divide into small discussion groups to relate the lessons of these Shakespearean scenes to their own company practices. The groups report back to the whole seminar on whether and how the company handled the situation better (or worse) than King Henry V, Portia or Claudius.19

Ken and Carol Adelman of Movers & Shakespeares

Notice that the Shakespeare stuff is ancillary to the organizers’ expertise and résumés: “their extensive experience in top positions in government, public corporations, and non-profit groups,” to quote the Web site once again. Just as “no prior knowledge of Shakespeare is required” of participants (and quite reasonably so), likewise the directors of Movers & Shakespeares are, so to speak, Movers rather than Shakespeares. They have picked up their Shakespeare along the way. Carol Adelman is the president of Movers & Shakespeares, and her résumé tells us that she has “over 25 years of theatrical experience,” but her doctorate is in public health, and she has worked in government as the “top official for the first President Bush on US foreign aid to Asia, the Middle East, and…Eastern Europe.” Her husband, with “years of teaching Shakespeare” at Georgetown and George Washington universities (I am, again, quoting his résumé) has a doctorate in “Political Theory” and a master’s in “Foreign Service Studies.”20

In short, it is because of their credentials in government and business, not in English literature, that the Adelmans have clout in the world of the leadership institute. The real subject is leadership, and “Shakespeare” is the image or comparison being used to convey the point. Contented clients like Northrop Grumman Mission Systems, General Dynamics Armament and Technical Systems, Ocean Spray products, and the Wharton School of Business have written testimonials to Movers & Shakespeares, testifying to this program as a suitable authority to advise business executives. Shakespeare in Charge, the book Adelman coauthored with Norman Augustine, chairman and CEO of Lockheed Martin, was blurbed by Colin Powell and Warren Buffett.21

What does Ken Adelman have to say about Henry V? “Superb leadership, of the kind King Henry V displays, can compensate for shocking shortcomings elsewhere…. In Henry V we have a man at the apex of both the power and leadership scales. Watching Henry up-close-and-personal shows us a leader working brilliantly with his executive staff and lowly subordinates alike, a grand strategist who focuses on detail, a man whose private doubts and fears remain concealed as his public persona exudes confidence, a motivational speaker who peps up his team right before they take the field, and a warrior-commander who inspires them and drives them on to victory.”22

The hanging of Bardolph is, for Adelman and Augustine, as it was for Corrigan, a crucial executive decision for King Henry, “the need to carefully evaluate his key staff and eliminate the bad seeds. Finding them, he gives them the ultimate pink slip.”23 About the Crispin Crispian speech, they say, “Successful corporate leaders inspire people to dig deep within themselves, which makes that critical difference between victory and defeat.”24 The longbows are said to come from “the Welsh forests—the Silicon Valley of that era.”25 Much of the rest of the book’s opening chapter, “Act I: On Leadership,” is devoted to the activities of “shrewd business leaders…like Henry,” including Richard Branson of Virgin Atlantic; Todd Wagner, who pioneered putting sports events on the Internet; Jake Burton Carpenter, designer of the snowboard; and so on.26 “While Henry doesn’t have the luxury of a policy-planning staff and off-site strategizing meetings, he proves himself a great leader in identifying and then pursuing a clear vision.”27

Just about every book on Shakespeare and business singles out Henry V as a model for modern leadership. In Jay Shafritz’s Shakespeare on Management the “once more unto the breach” passage in Henry V is called “one of the greatest motivational speeches of all time,” and Henry himself “a practitioner of the path-goal leadership style.”28 “A little touch of Harry in the night” is said to illustrate Tom Peters’s theory of “management by wandering around,” and the Crispin Crispian speech shows Shakespeare as a “managerial psychological par excellence.”

What should we think about such an appropriation of Shakespeare? Certainly nothing is more symptomatic of “modern culture” than using Shakespearean characters and plots as the jumping-off points for discussions about business ethics and management decisions. Nor are these “readings” of the plays bad readings. They’re perfectly sensible, as far as they go. They are presented, of course, as if they had been generated independently of any scholarship on the topic (there are no footnotes to literary scholars, Shakespeareans, or Shakespeare editors, although there are periodic footnotes to, or citations from, business texts). Corrigan devotes a substantial chapter to a reading of Henry V and to the story of King Henry as it was set out in the two previous plays, Henry IV, parts 1 and 2, where, as the madcap Prince Hal, he goes about consolidating his support with the underclasses by drinking with them, speaking their jargon, and associating with marginal characters in taverns and brothels. This is described as good preparation for leadership, as indeed it is. Adelman and Augustine are far less systematic in their treatment of the plays, using specific lines and incidents as springboards to discussions of modern-day tycoons and business decisions.

If we look at yet another one of these books, Thomas Leech’s Say It Like Shakespeare, we find the role of each play and character even further fragmented, since the chapters are divided not by play but by business or management topic. Thus King Henry’s nighttime walk among the troops on the eve of battle is cited in a chapter that urges “First, Do Your Homework,” under a heading called “Know the Territory” that also includes “the sales guys” in The Music Man and the miscalculations of Custer and of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.29 A chapter called “Gather Your Team: Once More Unto the Breach!” begins with the “we few, we happy few, we band of brothers” quotation to introduce the idea of working in “tiger teams, task forces, and IPTs (integrated project teams)” for optimal communication in business today.30 The book ends with the Crispin Crispian speech, printed in full, followed by the suggestion that “if you read this aloud, you may feel an irresistible urge to head off for the recruiting office. This is regarded by many as one of the most powerful communications in the entire Shakespeare repertoire.”31 Again, this book’s footnotes are all to business books, newspaper articles, books of famous insults, People Skills, and so forth.

There seems no reason not to welcome any modern discussion of Shakespeare, however attenuated from the actual plays and their language—as with films and books that take off from Shakespeare plays, like A Thousand Acres or 10 Things I Hate About You (a “teen remake” of The Taming of the Shrew, in which my favorite character, the father, is called “Walter Stratford”). But this kind of work is not useful in illuminating, analyzing, or interpreting Shakespeare. It uses Shakespeare, but the use is not commutative. It does not go both ways. Taking problem sets from Shakespeare’s plays and posing them as moral or ethical or decision-making problems flattens them out rather than teasing out their ambiguities and internal contradictions. The “Henry V” of these examples is a construct, a product of a management exercise or of a motivational speaking course.

Leadership is not a literary, intellectual, or analytical category. It is a word of instrumentality, avoiding ambiguity rather than seeking it. And it assumes that Henry, whoever he is, has a plan, a design, and an objective that can be imitated with profit—and for profit. (Thus none of these motivational exercises allow for the reversal of fortune that is announced by the epilogue, or for any of the myriad hints in the play that trouble may be just outside the boundaries of its controlling myth.) Yet the richness of the play depends, precisely, upon its eluding these determinative, end-stopped boundaries. The darker Branagh interpretation is always encoded within the more optimistic Olivier interpretation. The 2003 Nicholas Hytner production at the Royal National Theatre of Great Britain was described as “hugely controversial” because of its “deglamorization of Henry’s war and its implied criticism of those who mount the ramparts under false pretenses.”32

What is the literary keyword I would suggest for Henry V? It is certainly not “leadership.” But it is a deceptively close, and deceptively distant concept—the concept of “exemplarity.” Being fit to serve as a model or pattern.

Henry V’s great speeches, both “once more unto the breach” and the Crispin Crispian speech (“we few, we happy few, we band of brothers”) are taken by these motivational professionals as the exemplar of what a good leader should and can do, in the office as on the battlefield, in the warfare of multinationals as well as in the football locker room before the big game. But the literary-critical category of “exemplarity” is more complex and more double-sided.33

How can something be an example, if it is also an exception, and a unique event? Of what is it exemplar? Literary characters are often taken to be “examples” of something that is also “universal”—thus Henry is a king, a young man with a wild past, a general, an Englishman (or a Welshman), a historical figure, and so on. And some generalists will want to claim that such categories are examples of “human nature.” Motivational books tend to present him as an exemplar of the good leader, the manager, the decisive business professional. But because he is embedded in a literary text, and is in fact constituted by that text, “Henry” is also a site of contestation and contradiction. Is he really in love with Kate, or is the marriage purely a political convenience? In the play he speaks plausibly on so many occasions, to so many publics and individuals—and in Henry IV, Part 1, the character of Prince Hal (who will become Henry V) says in soliloquy, to his offstage low companions (and to us in the audience), “I know you all, and will awhile uphold / The unyoked humour of your idleness” (1.2.173–74). That Hal was using his friends, and using us. Is this the same character? When Henry V is taken as an example, whether of the ideal military leader, or the concerned king, or the motivational speaker, what does his language really say? Making him an “example” of these categories is a back-formation, drawing his supposedly exemplary nature from our presuppositions about what the text, the play, means. The reasoning is circular; he becomes an example of that of which we posit, on the basis of our interpretation—or use—of his character, that there is a universal to be exemplified.

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Representative Men labels Shakespeare “the poet,” Plato “the philosopher,” and Napoleon “the man of the world.”34 This is a kind of exemplarity in biography, history, and citation—somewhat different from exemplarity when applied to a literary character or work. Critic Jonathan Culler writes:

The power of literary representations depends upon their special combination of singularity and exemplarity: readers encounter concrete portrayals of Prince Hamlet or Jane Eyre or Huckleberry Finn and with them the presumption that these characters’ problems are exemplary. But exemplary of what?…It is as critics and theorists that readers take up the question of exemplarity.35

In a similar spirit, the philosopher and theorist Jacques Derrida discusses the word “iterability,” that which can be repeated, which is related to the concept of exemplarity, that which is taken as an example: “iterability makes possible idealization—and thus, a certain identity in repetition that is independent of the multiplicity of factual events—while at the same time limiting the idealization it makes possible: broaching and breaching it at once.”36

Once more unto the breach. The breach in the wall is what allows for broaching the beginning of a conversation or discussion. It does not close; it opens. Henry V has been taken as an exemplar for the extraliterary world, the world of business, commerce, government, politics, and war. But he remains also a figure both broached and breached, presented and riven, divided within himself and within the play that bears his name. Infinitely repeatable, every time the same but different. Like acting, like theater—like Shakespeare.

Shakespeare’s plays almost never end where you think they are going to end, and where they seem to “promise” to end. In Much Ado About Nothing the wedding is deferred till after the play is over; in Macbeth we do not yet see Malcolm “crowned at Scone.” We tend to say that comedies “end in marriage,” but often—as, for example, in Twelfth Night—the marriage is promised but not performed. Henry V is no exception. It ends not with the marriage of the English king and the French princess, although act 5, scene 2 seems to close on that promise (“Prepare we for our marriage,” says the king, and concludes in the future tense and in the optative mood, expressing a wish: “Then shall I swear to Kate, and you to me, / And may our oaths well kept and prosp’rous be” [5.2.342; 345–46.).

But neither the royal couple nor the audience gets to enjoy this promised end. Instead the Chorus enters to tell us that this was all a moment, and that it is already over. In the space of a sonnet, a short fourteen lines (much shorter than any of the Chorus’s prologues) we learn that Henry V lived a “small time,” though “in that small most greatly lived,” and that his young son, Henry VI, though he was left “imperial lord” of France and England, was badly advised: “Whose state so many had the managing / That they lost France and made his England bleed” (Epilogue 5–14). I suppose that we could regard this as a direct lesson in leadership: take control, don’t put your business in the hands of too many managers, make sure the person in charge knows what he is doing. But if this is the “takeaway,” then perhaps we no longer need the play, but only a set of prose maxims.

Henry V ends where it begins, with the Chorus describing—brilliantly and eloquently—the inadequacies of the playwright and the stage: “Thus far with rough and all-unable pen / Our bending author hath pursued the story, / In little room confining mighty men, / Mangling by starts the full course of their glory” (Epilogue 1–4). The sonnet epilogue here is in tension with the drama, with the dramatic action we have just seen and heard. Like a news bulletin, these unwelcome words interrupt the program. We “know” that, offstage somewhere in the imagined world of act 6 of this play the marriage took place, the lands were unified, the love story continued, the heir was born. But what we see and hear is something different, a story of death and of loss, not what we thought we were watching, a story of love and of victory. The king, the hero, the motivational speaker, disappears. What remains is the image of the “bending author” and the brevity of the moment, historically and theatrically speaking. The paradox of exemplarity, the impossibility of a singular paragon who is also an example or a model, requires us to remember the frame, to take the Chorus seriously as part of the play, and to recognize that what is most “Shakespearean” about this ending is the way in which it refuses to let us think we have clinched the deal.