Gaël Monfils

“I’m ready to die for that, to win a Slam.”—Gaël Monfils

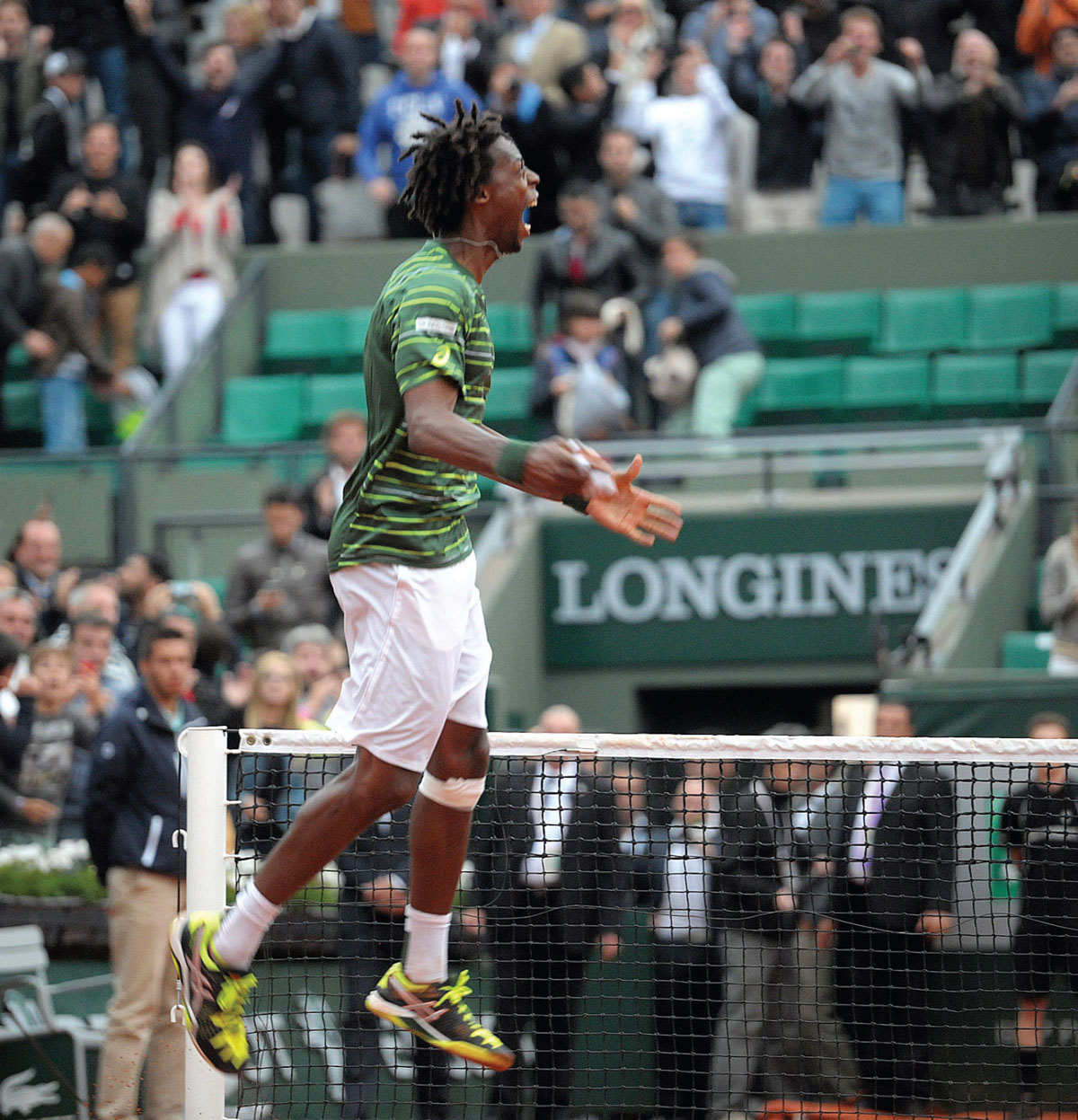

On the court, Gaël Monfils is elegant, beautiful, and supremely athletic. He slides, slips, leaps, dances, tumbles, dives, laughs, and yells. “La Monf” (a nickname—another is “Sliderman”) moves like lightning. He seems able to return any ball, no matter where it goes and no matter how it gets there. As Ben Austen wrote in the New York Times Magazine in August 2017, “He is a player who crackles with the possibility that, at any instant, he may do something beyond the limits of physical laws or human capabilities or merely the respectable conventions of tennis.”

Nodding their heads and wagging their fingers, the tennis gasbags say, “He may be a brilliant athlete, but he is lazy, tactically weak, erratic, passive, petulant, exasperating, and a show-off.” “La Monf is a punk,” says one. “He is a troubled genius,” says another. “He plays to the crowd.” “He’s more interested in entertaining than playing tennis. “Andy Roddick, onetime World No. 1 and 2003 US Open champion, has said that Monfils “Showboats when winning and rolls over when down.” When he played Djokovic in the 2016 US Open semifinal (he lost), one news account described his stance when receiving a serve as “looking like someone waiting in line to place his takeout espresso order.” Former Top 10 player Henri Leconte said in 2012 that Monfils “is completely lost.” But, added Leconte, “Beware if the beast awakes.”

His career has been erratic in the extreme. In 2011 Monfils was ranked No. 7 in the world. In early 2013, following months of being sidelined by injury, he dropped into professional tennis purgatory, ranked below a hundred. He went into 2013 Roland Garros at No. 81, and by the end of the tournament had clawed his way up to No. 67. “I never check the rankings,” he says, but no one believes him. All tennis players check the rankings. By Wimbledon 2015, his career partially revived, Monfils was ranked No. 18. At the beginning of 2017 he was back to No. 7. By April he had dropped ten places, to No. 17. At the end of November he was No. 46. He has never been in a Grand Slam final.

In a rally, Monfils typically shows total commitment.

Committing himself mentally more than his body can handle physically, Monfils often gets injured.

Monfils is one of the most expressive tennis players on the ATP Tour. This photograph was taken at Roland Garros 2015.

He is, it seems, always injured. He has injured his knees, hips, back, hamstrings, leg, ankle, shoulder, groin, abdomen, wrists, and stomach. He has retired from matches in Bucharest (2013), Madrid (2011 and 2006), Stuttgart (2010), Shanghai (2009), Australia (the 2009 Open), Cincinnati (2008), Rome (2008), Szczecin (2007), Monte Carlo (2007), London (2006), and Bastad (2005). He has failed to start a match (called a “walkover,” with victory awarded to the player who shows up) in San Jose (2011), London (2009), and Rimini (2004). He missed several months in 2012 because of a right knee injury. He dropped out of the 2015 Miami Open (hip). In 2016 he skipped Roland Garros (virus), the Paris Masters (rib), and the Davis Cup quarterfinal (knee), and pulled out of ATP World Tour Finals in London (rib). In 2017, he withdrew once more from Miami, from the Davis Cup quarterfinal (knee and Achilles tendon), and retired during his third-round match at the US Open. The French Davis Cup captain, Yannick Noah, has said of Monfils that there is a “lack of investment,” that Monfils gives priority to his “personal goals,” and that he “needs to prove he is really motivated.” He is said to suffer from periodic depression. Some of this, presumably, is the price he pays for his extreme physicality.

From time to time, the career of Monfils seems to be in tatters, yet he always claims not to be worried. He frequently describes himself as very relaxed. He has won about $13 million in prize money. His ambition, he says, is to win the French Open, to hoist the Coupe des Mousquetaires, but it now looks increasingly unlikely that Monfils, who was born in Paris in 1986, will be the French player to revive the glory days of Yannick Noah, winner of Roland Garros in 1983, the last Frenchman to win in singles at that tournament. At the 2015 French Open, Monfils was easily beaten by Roger Federer in the fourth round. In 2016, he didn’t compete (he had a virus). In 2017, Stan Wawrinka beat him, again in the fourth round.

John McEnroe, once a bad boy himself, and famous for temper tantrums on the court and berating officials, once went into a tirade on television about Monfils. It occurred during the first round of the 2013 French Open when Monfils (who, in his eighth French Open, this time needed a wild card to enter the tournament), played Tomáš Berdych, a Czech seeded fifth. According to McEnroe, the French had stopped believing in Monfils, and that was why the stadium was only half-full. He said Monfils was unable to embrace competition; had a fear of failure; could not deal with the ups and downs of the game; had a hard time emotionally; had completely slipped off the map; waited for the other player to lose the point, rather than trying to win one; had had at least eight coaches, and that his various coaches were fed up with his low commitment level. But the stadium filled up, and Monfils played brilliantly against Berdych. By the end of the match, which lasted four hours, McEnroe had changed his tune. “Marvelous first-round tennis,” he said. The New York Times tennis blog commented, “Gael Monfils summoned the magic of Court Philippe Chatrier. . . . Monfils served extraordinarily well. . . . Monfils held serve by managing his service game to near perfection.” Monfils beat Berdych in five sets, 7–6, 6–4, 6–7, 6–7, and 7–5. “It’s magic here,” he said at the press conference following the match. “This victory is beautiful.”

Monfils is known for hitting the ball from almost impossible positions. This photograph was taken at Rogers Cup 2016.

It wasn’t the only time that McEnroe had something to say about Monfils. In the second round of 2013 Roland Garros, Monfils played the Latvian Ernests Gulbis. At the beginning of the game, McEnroe said Monfils’s entertainment value is high and his predictability value low and that he expends far too much energy early on, and then has nothing left. Of a Monfils serve, McEnroe said, “That’s one of those ‘I just don’t want to double-fault’ serves.” When Monfils seemed to hobble a bit, McEnroe commented, “It’s a good time to try and get a little sympathy.” But once again, Monfils played superbly and beat Gulbis in four sets, after dropping the first. The New York Times said, “the quality of the exchanges was routinely spectacular, with the most eye-catching material coming when Gulbis flexed his muscles and Monfils stretched and stretched his elastic limbs and absorbed all of that controlled fury.” The Guardian was eloquent: “Something special illuminated the eddying gloom of Roland Garros on Wednesday. Over three and a quarter hours, Ernests Gulbis, a Latvian of volcanic temperament, and France’s elastic magician, Gaël Monfils, enthralled the patrons of Court Philippe Chatrier with tennis that encompassed all the arts, from touch to power.” In the third round, Monfils, despite having four match points, was defeated by the Spaniard Tommy Robredo, 2–6, 6–7, 6–2, 7–6, 6–2. “This is unbelievable!” said McEnroe.

Roland Garros 2017, first-round match against Dustin Brown.

How to sum up Gaël Monfils? Many words have been used to describe the energetic player who sports tattoos of the islands of Guadeloupe (father’s origins) and Martinique (mother’s origins) on his arms—brilliant, naughty, a maverick, mind-boggling, incomparable, fun, kind, gracious, erratic, and comic. At his best, he is probably as good as they get. At the end of 2017 he told a journalist, “My goal is still to win a Slam, you know. I’m working for that and I’m ready to die for that, to win a Slam.”