CHAPTER 7

Weaknesses: Embracing Them, Working with Them, Protecting Them

Let me get this out of the way first: none of becoming a Super You is about eliminating every perceived weakness you have. Not at all. Creating a Super You isn’t about eradicating all weaknesses; it’s about learning to recognize them for what they are—part of you—and finding ways to work with them. Some weaknesses deserve to be cradled and considered part of the charming package that is you, some weaknesses can be improved upon for your overall health, and some weaknesses can be reframed and made useful to you. As no one is perfect, no one is without flaws. But instead of hiding those flaws and making apologies for them, let’s treat them as superheroes do: just another thing about us. Superhero weaknesses make them more relatable to us mere humans, and show us how even the best of us have to find a way to work through our weak spots. Our human weaknesses can become a more useful, more beloved part of us if we start looking at them more objectively.

After saying all that, I want to add that I don’t even really like the term “weaknesses”; but it works within the superhero universe, and so here we are.

It is absolutely your choice whether or not you strive for improvement—and when I use the word “improvement,” in no way do I mean “optimal emotional health.” In fact, you don’t even have to be healthy all the time. What we’re looking for is an overall push toward healthy behaviors and attitudes. But within that scope, of course you’ll still have days when you dwell on negatives, when you make terrible choices, and when you hold on to your weaknesses like a kid with a blankie. It takes all of these days to make a person, and a life.

Let’s break down personal weaknesses into two distinct categories: less-than-stellar qualities we can improve with some modifications in thinking and behavior, and less-than-stellar qualities we cannot change that we therefore need to protect and understand and sometimes baby. Most of us have a pretty good idea of what our weaknesses are, but if you’re having trouble, think back to fights you’ve had with significant others or friends, think back to times that you’ve felt terrible and guilty, think back to the mistakes you make over and over, making sure that you’re focusing on yourself and not on the other party, and I bet you’ll unearth a few things. The big surprise here is realizing that most of the weaknesses you’ll discover can likely be improved upon to some degree if you choose to. Again, it’s also absolutely your option to see your weaknesses laid bare before you and think, “You know what? I’m keeping these a bit longer.” This is your Super You.

And as for the weaknesses we’ll be discussing here, obviously and unfortunately I can’t address them all, so instead I’m going to present and break down a few very common ones. If you’re feeling confused or overwhelmed by any of your weaknesses, note that they might be best addressed with a therapist one-on-one.

Weaknesses We Can Change

Let’s start with weaknesses that can be improved upon. To me, this would be a quality within yourself that has grown out of maladaptive circumstances or out of habit—it’s something you know isn’t great for you, but it feels so automatic it’s hard to know how to stop.

WEIRDEST SUPERHERO WEAKNESSES

The Human Torch’s Achilles’ heel was asbestos—long before it was discovered that asbestos is a carcinogen for human humans, too. He was ahead of the curve.

Wonder Woman was originally weak against men binding her bracelets together. A quote from that comic: “When an Amazon girl permits a man to chain her bracelets of submission together she becomes weak as other women in a man-ruled world!”

If Thor lets go of his hammer for sixty seconds, he becomes a human man and his hammer turns into a walking stick.

Weaknesses We Can Change: Sneaky Self-Destructive Behaviors

I have friends who will rail on about how drug addicts ruin their lives with their unhealthy behavior, and then not eat until dinnertime because they’re swamped at work. Not only do they not make the connection between the two unhealthy habits, but they fail to see their behavior as anything but noble, the badge of a hard worker. Of course, while hazardous substance abuse is a bit more severe than workaholism, don’t for a second think that intense overwork doesn’t jeopardize your health. Self-destructive behavior comes in many forms—but when it’s for the greater good, like burning yourself out at work, yes, it punishes you, but it also makes you look like a superstar for working so hard. Watch out for that sneaky trap.

I was self-destructive for years, first in a pretty obvious, after-school special kind of way, and later in this more sneaky way. I didn’t feel worthy of good treatment, so out of hatred of my body I put myself in dangerous situations and harmed myself in as many ways as I could. I was casual with my health and well-being. I kept people around me who were cruel to me because I was lonely. The more obvious self-destructive behaviors of people in this mindset might include:

Picking fights with people who care about you out of wanting to release anger

Picking fights with people who care about you out of wanting to release anger

Substance abuse (not just use, but abuse)

Substance abuse (not just use, but abuse)

Unsafe sexual promiscuity

Unsafe sexual promiscuity

When I grew up a bit and went to graduate school, I proudly announced myself “cured” of my self-destructive habits because I no longer did risky things that made my friends shake their heads and proclaim I was nuts. During this time I had regular sixteen-hour days—classes, internship, two jobs—for which I perfected the art of eating while driving. I chose to work constantly rather than take on loans and long-term debt, and I took on extra responsibilities because I wanted to get as much out of the experience as I could. But these choices quickly surpassed “useful” and drove deep into self-destructive territory. The truth is that graduate school itself is self-destructive—it just has a positive goal. Some of these less obvious self-destructive behaviors include:

Getting into Twitter fights with strangers

Getting into Twitter fights with strangers

Hooking up with lots of partners in a way that makes you feel small

Hooking up with lots of partners in a way that makes you feel small

Not giving yourself any downtime

Not giving yourself any downtime

Then, when I graduated and found my first real job, I still burned the candle at both ends, mostly out of feeling as if it was the only way to be an effective adult. My effectiveness had to come at the cost of my health. At some point I realized I needed to do more work on myself: I needed to address why I felt the need to harm myself physically and emotionally, regardless of the cause. For me, self-destructive behaviors boiled down to feeling like I needed to apologize for my existence, and offering myself up as a sacrifice and an apology.

So how about you? Let’s say you consistently put other people’s needs ahead of your own. Now, if confronted about such behavior, you might say: “But I have to live like this—if I don’t take care of this stuff no one will.” Or: “Yeah, but I’m not hurting anyone but myself!” Unless you’re working toward a goal with an end in sight, like a website launch or a degree, responses like these are a sign you need to make some changes. No life should consistently burn out so that the rest of the world can run smoothly.

If you’re not sure whether you’re exhibiting self-destructive behaviors, take a moment with your notebook and list the kinds of things you do regularly. Then, focus on them one at a time: are there any things there that you’d object to your best friend/lover/parent/child doing?

Once you start to see any self-destructive behaviors in yourself, it’s time for that good old two-pronged approach to change: internal observation and external change. Internally, start asking yourself a few questions about your self-destructive behaviors.

Does this behavior happen because you fear stopping it would hurt other people?

Does this behavior happen because you fear stopping it would hurt other people?

Does this behavior happen because you want to help achieve a group goal?

Does this behavior happen because you want to help achieve a group goal?

Does this behavior (handily) keep you from confronting other parts of your life that you’d rather not address?

Does this behavior (handily) keep you from confronting other parts of your life that you’d rather not address?

Does this behavior make you feel needed by others?

Does this behavior make you feel needed by others?

Does this behavior make you feel worthy?

Does this behavior make you feel worthy?

Is this behavior, and its effects, something you feel you deserve?

Is this behavior, and its effects, something you feel you deserve?

The Hidden Benefits of Self-Destructive Behaviors

Next let’s dig into the darker, more hidden benefits of self-destructive behavior. Yes, working until 11:00 every night gets stuff done and makes you look like a hero at work—but what else is it doing? Are you so swamped that you don’t have time to date or nurture intimate friendships? Or let’s say you are dating, but you date men who don’t have their shit together. Sure, making all the relationship decisions means you’re in charge of the relationship—but what else does it mean? Is it a relief to know that the child-man won’t leave you because he literally can’t exist without you? (Note: this was me for most of my twenties.)

Now, while it’s a bummer to identify self-destructive behaviors, it can also be somewhat of a comfort to realize that almost all of our behaviors, even the self-destructive ones, aid and assist us in some manner. But, in the same way that burning down a house in order to get rid of a spider in the kitchen destroys more than the spider, our self-destructive behaviors often serve their purpose while creating a host of new, possibly worse problems. The good news is that understanding in what ways these behaviors are trying to help is a good step in learning how to alter them.

Sneaky Self-Destructive Behaviors: The External Fix

While you’re considering that clumsy oaf of self-destruction and how it’s trying to help with its big dumb hands, let’s start making some external changes to help us get out of our rut. I find the key here is to start slowly, and one great way to do that is with an exchange. The exchange is a great technique for phasing out unhealthy behavior and replacing it with healthy behavior. Essentially, for every unhealthy behavior that you can’t yet give up, add one healthy behavior. Here’s what I mean.

In my first real job after grad school I worked at a residential facility, which meant that my clients lived on campus whereas I got to go home. I felt very guilty about this. I would stay until 9:00 PM some nights because someone always needed me, and I didn’t want to leave when I was needed! (Bonus: I love feeling needed.) So I made a deal with myself: for every hour I stayed late, I would have to exercise for twenty minutes. That way, staying three hours late meant that I got home at 9:00 and then had to go on a walk until 10:00. I’d be exhausted and miserable at the beginning of my walk, but then I’d be tired and calm by the end of it. So, if I chose to stay late, the exercise helped negate the effects of working too long—and if I didn’t want my day to end at 10:00, then I had greater incentive to leave work earlier. Basically, the beauty of this technique is that the only way to get out of doing the healthy behavior is to stop doing the unhealthy behavior that “necessitated” it.

So now, how can we apply this approach for you? Here are some unhealthy/healthy behavior combos that might be useful:

For every time you hang out with a friend who is not supportive, make a date with a friend who is supportive.

For every time you hang out with a friend who is not supportive, make a date with a friend who is supportive.

For every meal you eat in a rush, plan a leisurely meal in recompense.

For every meal you eat in a rush, plan a leisurely meal in recompense.

For every drink you drink to unwind, exercise for twenty minutes.

For every drink you drink to unwind, exercise for twenty minutes.

Write down in your notebook a few unhealthy/self-destructive behaviors you’re having trouble giving up. If you need help finding healthy behaviors to trade them for, refer back to Chapter 5 for suggestions. We all know Super You is a strong, tough creature, but she has enough to deal with from external forces—let’s help her not destroy herself from the inside out.

Weaknesses We Can Change: Expectations Without Communication

We all have preferences in how we want the people in our lives to treat us, whether or not we’re even aware of them. For years I expected everyone I got into a relationship with, platonic or romantic, to come into it having already memorized my owner’s manual. (Not that such a manual exists, and not that I wanted the other person to own me in any way, obviously, but you get the metaphor.) This is where I’m somewhat envious of superheroes, because everyone knows everything about them. Everyone knows not to bring up the topic of parents around Batman. Everyone knows not to bring Kryptonite around Superman. Wonder Woman doesn’t have to explain her invisible jet to anyone. But alas, we are not superheroes, and we have no manuals.

But I expected others to know all my preferences simply based on the fact that we were in a relationship together. See if this sounds familiar to you: you get together with the love of your life (or of right now) after a long, terrible day, and all you want is to be babied and snuggled. But said love of your life has also had a long and crazy day, and starts excitedly telling you about it as soon as you both sit down. As he’s talking and gesticulating wildly, a voice in your head asks, “Is he going to even ask me about my day?” You dramatically sigh while listening to him and nodding, and the voice pipes up again: “Can’t he tell I’m sitting over here miserable, while he just keeps going on and on about how Seth Rogen tweeted at him?” followed by the dreaded, “If he doesn’t at least ask me how I’m doing in the next minute I’m going to be soooo pissed.” And of course, the next step is working yourself into a lather of anger over something your one-and-only had no idea was happening. You were expecting psychic perception of a normal human being with no extrasensory powers. So you essentially set up a test that no one could ever pass: in truth, they are destined to fail. Does this sound familiar? (We’ll return to this scenario in a later chapter.)

This was one of the biggest weaknesses of my Super You. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve gotten caught in this trap—I essentially used to live in this trap. When it came to my close friends, my family, and the men I’ve dated, rather than helping them understand the blueprint of me, I’d create a dream scenario of how things should be—and then watch as no one ever came close to it. I justified this behavior by thinking, “Well, this is someone who’s supposed to know me well. I shouldn’t have to verbalize when I’m having a bad day.” And while it’s true that gradually, through trial and error, we learn the moods of the people around us, the possibilities of behavior are too infinite for us ever to know how to respond perfectly. Here’s the truth: it’s your job to know how you like to be handled under duress, and it’s your job to communicate those desires. It is not a qualification of caring about someone to be able to read his or her mind.

The Hidden Benefits of Expectations Without Communication

If we’ve learned that all behaviors, even the maladaptive ones, have some sort of benefit for us, even if they’re kinda creepy and gross, what on Earth do we get out of not communicating our wants while still expecting those wants to be met? What do we get out of deliberately setting up others to fail in our eyes?

For me it was a combination of things. As I’ve mentioned, I’m southern, and there’s a very real pull within me never to seem too demanding—never to bother anyone, really. This may be a fairly universal feeling for women; it’s certainly something I share with my mother. When I lived in New York, the first time my parents visited me I wanted to go all out and show them all the sights, but I was too poor to afford cabs everywhere. So I ran them all over Manhattan, and when I asked if they wanted to take a break, they’d say, “No, of course not, we’re fine!” Eventually I wanted a break, and suggested we rest in a park, and as soon as we did my mother said, “Good gracious, I thought we’d never stop. I just need a minute off my feet!” She hadn’t wanted to seem like she was pausing the fun—but that came at the expense of her physical comfort. She’s a fantastic mother, and of course I’d have been willing to break whenever she wanted. Experiencing this with her helped me to see the ways I do the same thing, that part of the reason I don’t communicate my needs and wants is that I want to be easygoing. To my mind, I should be happy just to be in a relationship, so making demands on how to be treated within that relationship would be too selfish.

Returning to why I didn’t ask for attention at the end of that bad day: perhaps I was worried that I’d risk seeming too vulnerable by needing emotional support from another person. Real relationships are full of squirmy, risking-your-coolness moments, and for a long time I wasn’t ready to accept that. Or maybe, instead of all that, I just didn’t have any good outlets for my anger, and relished the idea of expressing anger to someone close to me. Having a boyfriend who didn’t know how to comfort me confirmed my belief that the world was always going to be messed up and I’d always end up feeling lousy because of it. While this might sound nihilistic, this was how I felt before my Super You days. In fact, sadistically and gleefully anticipating being angry with someone for messing up yet again is another terrible new emotion we don’t have a name for. But name or no name, it absolutely exists.

Expectations Without Communication: The External Fix

If you find yourself guilty of expecting psychic behavior from those around you, regardless of your reasons for falling victim to this common Super You weakness, there are a few things you can do. But be warned: they involve showing vulnerability. Think back to the reality show technique we discussed previously. If someone in your life doesn’t have access to your talking head segments (so that means literally everyone, unless you actually have a reality show), it is incredibly important for you to communicate what you feel and what you need—for you to essentially show her your talking head segments. And if you haven’t yet figured out what you’re feeling and what you need, then it’s even more likely that the other person isn’t going to be able to figure it out either.

So, if you find yourself getting frustrated because you’re not getting what you want from the other person, stop and ask yourself what the ideal behavior would be she could do right now. Check in with yourself, as we talked about in Chapter 5. Once you’ve figured out the ideal response to how you’re feeling, take a step backward and ask yourself why that behavior is what you need. What is going on within you that would make a hug/a quick romp/dumping your woes out the thing that would help you feel better? Then your job is to communicate thus:

Hey ______, I’m feeling pretty ______ today. I would like you to ______. It would make me feel so much better.

Also, when you communicate what you want from the other person, make sure the request is both reasonable and concrete.

The unreasonable requests are unreasonable because either they’re not realistic (“Quit your job and stay at home”) or they’re so vague no one would know how to fulfill them (“Just understand me”). Plus, unreasonable requests can force the other person to translate what something like “understanding you” actually means. Be aware that making this request in no way guarantees you’ll get what you want, because—say it with me—you can only control yourself. But asking, rather than expecting, is way more likely to get you what you want.

Will this whole process be hard to do at first? Absolutely. Will you grumble that it takes out all the fun if you ask for it? Absolutely. But life is not an adorable romcom movie where two people’s souls come together with such ease and precision that they each anticipate the other’s needs. This is life, and it’s beautiful and messy and confusing.

I have two quick things to add here. One, it is absolutely okay to be a little needy sometimes in a relationship. Everyone has times—with parents, friends, lovers, coworkers—when they take turns leaning on each other. It’s a natural part of being in a relationship, and it should be a two-way street. And two, if you find that your calm requests for reasonable, concrete attention are consistently ignored outright or met with laughter or scorn, that’s a pretty good sign that the relationship is not worth your time and effort.

Weaknesses We Can Change: Negative Self-Talk

Have you heard of negative self-talk? If not, allow me to introduce you to something you might have been doing for a long time.

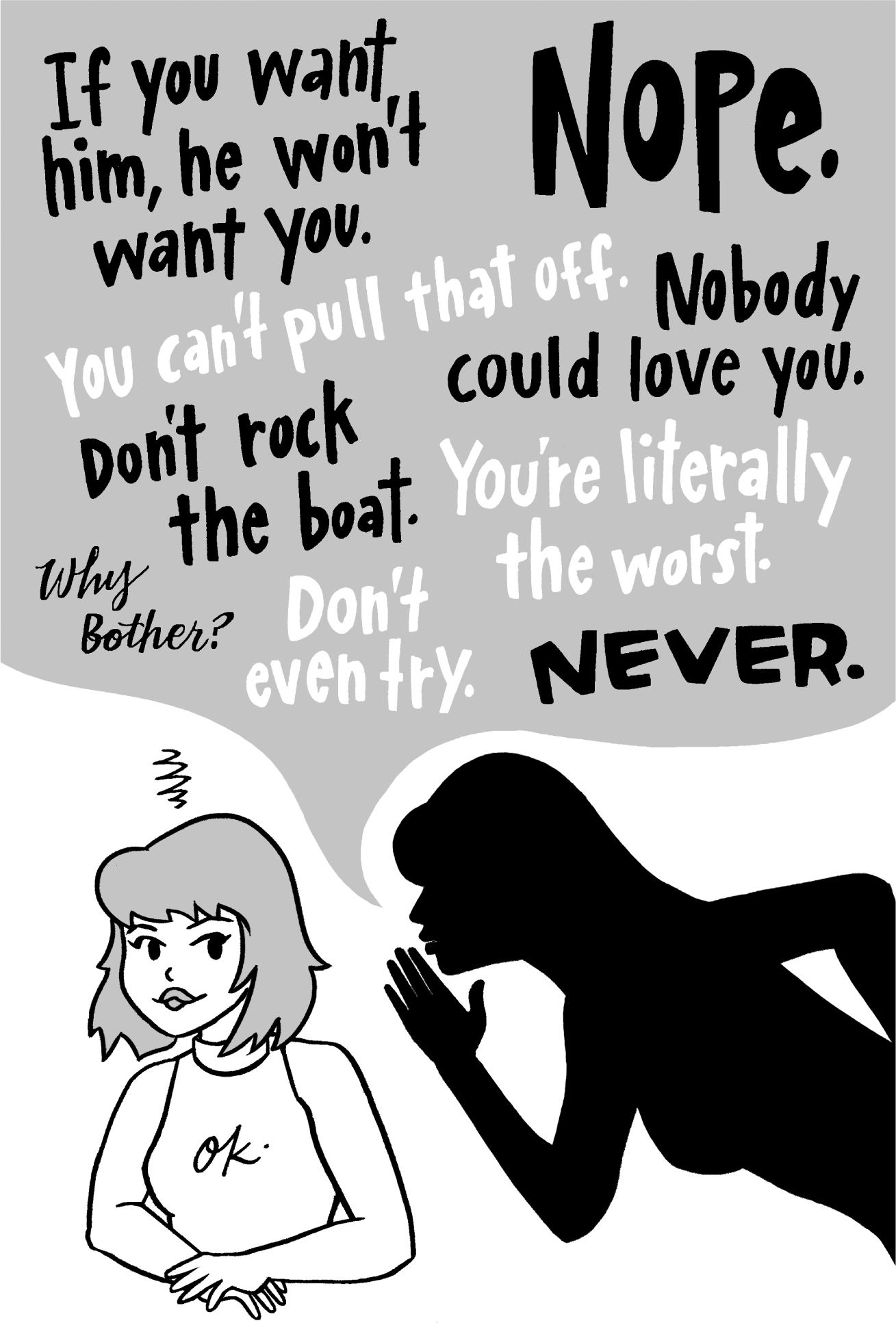

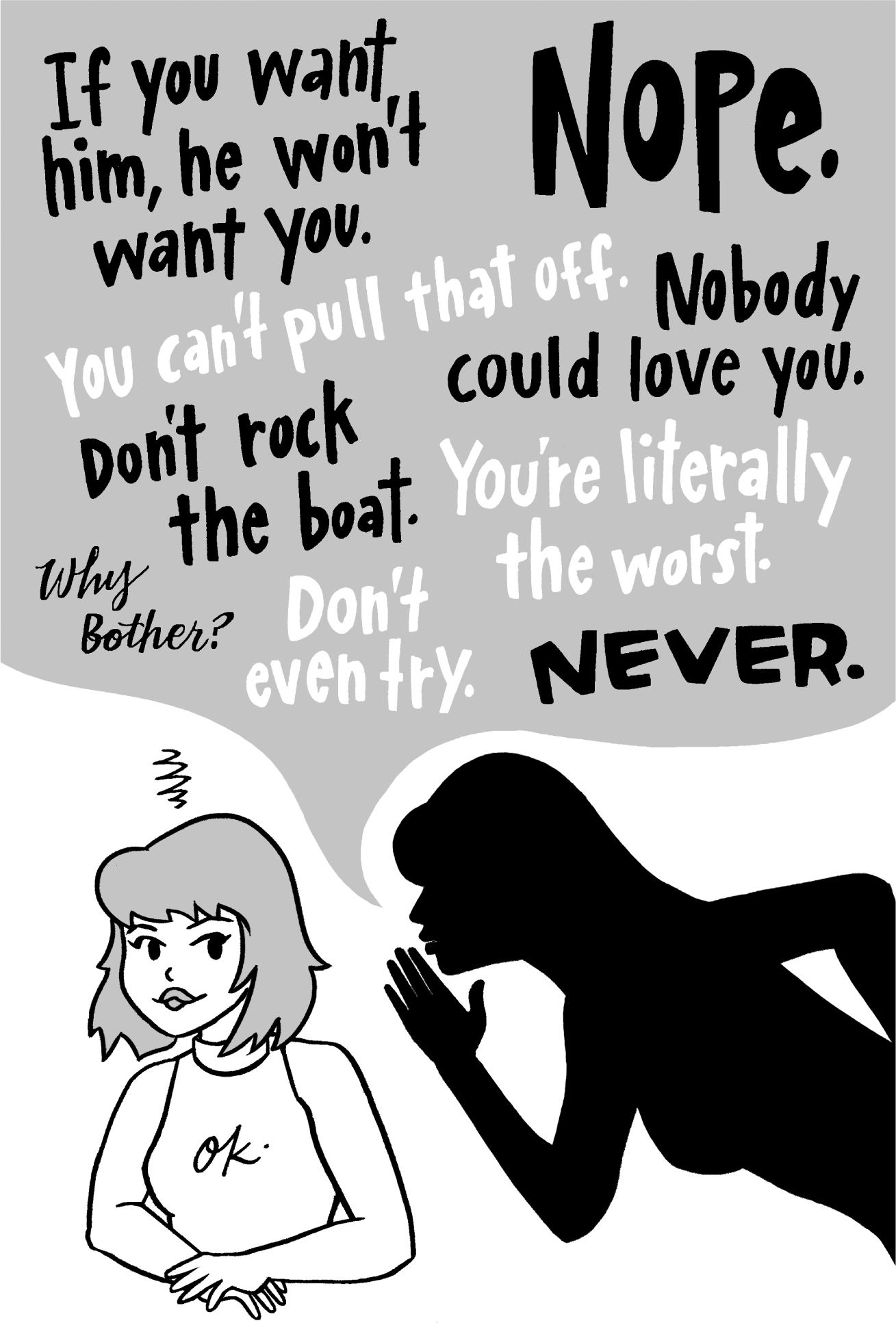

Negative self-talk is that little voice inside your head that tells you you’re not good enough, you’re not pretty enough, everyone hates you, and you’re going to look stupid. It’s the poisonous, repetitive inner voice that makes you doubt yourself in horrific ways, and the more vulnerable you feel, the louder it gets. I don’t know where negative self-talk comes from, but I also don’t know that it matters. Maybe it’s our culture or our parents. Maybe it’s mental illness, just one that everyone has. Maybe it’s Laura, the most popular girl in your middle school who used to tease you. All I know is that, at some point when I was very young, my negative self-talk started whispering in my ear and never stopped.

When I was very little, I was convinced that the cartoon mice on my bedsheets would come to life and bite me in my sleep. I tried desperately to sleep so as not to touch any of them, which literally tied me in knots. Try explaining that to your parents; I assure you, they’ll think you’re a basket case. As I got a bit older, I was plagued with constant, intrusive thoughts about the devil, and how I’d somehow created an accidental alliance with him. Eventually, rather than just scaring me, my negative self-talk started attacking me directly. So I had thoughts about being too big, and how no boy would want to be with someone bigger than him; of how I wasn’t worth anything, how I was stupid and should take up less space. This led to fantasies about my fat being a suit that I could zip off. Later, when I was dating, my self-talk would whisper to me that my boyfriend was cheating on me. Eventually, in my twenties, the voice settled on constantly yelling at me about my career and how it wasn’t going well enough. Basically, negative self-talk is a ridiculously obnoxious, passive-aggressive person who seems to exist just to torment you.

The Hidden Benefits of Negative Self-Talk

Remember how I said that all behaviors, even the maladaptive ones, have some sort of benefit for us? Well, guess what? There are no hidden benefits of negative self-talk.

So then what? How do we deal with such a toxic inner critic? Easy: we turn it into a creepy villain. As a Super You, you are destined to have a villain or two in your life; negative self-talk is simply the villain that worms its way into your head and tells you all the reasons why you’re not a Super You. But to turn your negative self-talk into a villain that you can then fight involves naming your negative self-talker, perhaps even coming up with a backstory for him/her/it . . .

Born out of the fires of hell, gas station employee for several years: miserable and obsessed with making you miserable too. She doesn’t even wash her hands after a visit to the bathroom!

Note that by doing this we’re not elevating our negative self-talk—in naming it we’re separating it from ourselves, shrinking it down, perceiving it as the nuisance it is. You know how sometimes in a public place there’ll be this one jerk on a cell phone talking way louder than necessary, so that everyone is treated to his scintillating conversation about mortgages or monster trucks? You know how eventually the sound of his voice goes from the only thing you can hear to a Charlie Brown/Peanuts teacher wah-wah that you register only as white noise? That’s what you have to do with negative self-talk, or with Mega Rhonda, which is what I named my negative self-talk.

Here to bug the shit out of you . . . it’s Mega Rhonda!

Because here’s what we forget about Mega Rhonda, or whichever negative self-talk villain we’re facing: it isn’t speaking the truth. It is, in fact, inaccurate. Believing our own negative self-talk is a totally natural inclination, because we want to believe that anything that comes out of our brains is somehow a deep, gospel truth about ourselves—but this just simply isn’t the case. Not everything your mind cooks up is genius, and just because the call is coming from inside the house doesn’t mean it has insight that you don’t have. It’s just Mega Rhonda, off work from the gas station, worming her way into your brain and trying to bring you down again. And though the negative self-talk spiel she gives may seem tailored to you, it’s actually not about you. It doesn’t need analyzing, it doesn’t need “grain of salting”—it just needs to be told to shut the fuck up, and it needs to be ignored. If this seems like a daunting task, think about how you’d respond to Mega Rhonda if she said all those horrible things to your best friend, little sister, child, partner, or parent. You’d deal with her immediately, right? You wouldn’t think, “Well, maybe you’re right, Mega Rhonda,” right? This is the same respect you owe yourself. You’re on Team Super You, after all.

Negative Self-Talk: The External Fix

So it’s time to start practicing this incredibly simple but hard-to-master technique. Today. When you hear your Mega Rhonda whispering negative stuff into your ear, realize that it’s coming from your personal villain, and tell it to shut up. Have I demurely murmured “Shut up” in an elevator on the way to a job interview? Sure. Have I addressed Mega Rhonda unkindly in a mirror in a dressing room at a store? Oh yeah. I absolutely think that an essential key to everyone’s self-esteem is based on how well you’re able to tell your villain to cram it. Eventually, you will notice the volume of your Mega Rhonda gradually diminishing. It may never stop, but your brain will adjust to the idea that the negative self-talk is just noise, that it doesn’t speak your essential truths.

Are any of you asking, “How can I tell the difference between negative self-talk and actual, helpful warnings?” Well, that’s a great question. And while, yes, some of the voices in our heads can be extremely useful to us, there is a big difference between instincts and negative self-talk. Negative self-talk is unequivocally negative and often irrational. It’ll use words like never, always, disgusting, permanent—you know, words that leave no room for hope or improvement. Instincts are the little voices accompanied by our skin crawling or by a pit of weirdness in the belly. Instincts tell us that we’re in an unsafe situation, or that our health is failing, or that our bodies need something from us. Not listening to these sorts of helpful warnings is not the same as not listening to a steady stream of insults and degradation. They are two separate voices entirely, and only one of them says things like “should,” “can’t,” and “Go ahead humiliate yourself, see if I care.” Only negative self-talk isn’t accompanied by physical sensations. So listen to your instincts, and tell Mega Rhonda to shut up. If you do it consistently enough, her voice will fade to a sad, raspy, little whisper that tickles your ear every once in a while and makes you feel just pity.

Weaknesses We Can Change: Hating

Next up: hating. I’m not talking about hating the main characters in your life; I’m talking about hating strangers, hating the minor characters in your backstory. Whom do you hate? And more importantly, who is worthy of your hatred? Because here’s the thing about hating: it takes a great deal of energy. I’m not going to use a tired analogy about the number of muscles it takes to smile and frown, but it is true that the amount of energy it takes to hate someone is often equal to the amount of energy it takes to care about someone—hate just involves more of a burning sensation. I would have said a few years ago that I have no enemies whatsoever, because I’m a grown-up, but the fun thing about the Internet is that it gives us such a wide array of people to hate, and such a wide variety of ways to hate them. You may hate someone on Twitter for her politics, you may hate someone you know personally for always posting about his awesome social life, you may hate someone for the essays she writes on the website you want to write for, you may hate someone for his success, or you may gleefully still hate someone named Laura who teased you in middle school, happy to learn about the nightmare her life has become. I once spent a lot of time and energy going through a woman’s Instagram profile and critiquing each image just because she threw a really cool birthday party and didn’t invite me.

The Hidden Benefits of Hating

Here’s a pretty basic lesson about hate: hating someone else almost always means that you have some unfinished business within yourself to attend to. Just as criticizing someone else often means that you are critiquing your own qualities that you are less than proud of. Think about it: If you hate someone for having a successful career, aren’t you actually feeling somewhat unsteady about your own trajectory? Or if you hate someone for being pretty, and say catty things about her to level the playing field, aren’t you actually addressing insecurities about your own appearance? If you hate someone’s amazing-looking social life on social media (I call it Instajealousy), isn’t that really about your lack of focus on your own social life? Or, similarly, if you hate an attractive person for being in your partner’s life, you’re probably actually addressing your insecurities with the relationship. I mean, if you feel successful and beautiful and secure in your relationship, what’s the reason to worry about where others may fall in those categories? The point is, whenever you hate someone for something, try to look beyond the person and the hate and identify the issue that’s pestering you.

This subject affects an awful lot of us, so I have a lot to say about it. And yeah, it’s easy to hate someone for being racist/sexist/homophobic—I totally get that—but isn’t it more that you’re upset with your lack of control over the world? Those others don’t deserve any of your energy, not even hate. And if you find yourself deeply hating a stranger for tiny offenses like not flushing a public toilet or parking weirdly, it’s usually a sign that you have some misdirected anger in your life. Daily events might deserve your momentary annoyance—but if you find yourself focusing on them for too long, it’s definitely not about the annoyance; it’s about a deeper unmet need inside of you.

Hating: The External Fix

Though hate can sometimes be galvanizing, hate-based motivation is more rare than you’d think. More often, hate paralyzes us, keeping us from doing anything to improve our situation.

In my case, hate kept me from looking inward, because I was too busy plotting the demise of Kim, that slutty girl at work that all the guys fawn over. Basically, I had a problem of hating attractive women—for years. First, I refused to admit they were attractive. I also convinced myself that attractive women were slutty and “unfeminist.” And I could sometimes be heard insisting they’d probably had traumatic pasts they were trying to bury with their primping. But not only did all that hate get me nowhere, I ended up much more stressed-out about my own appearance. I didn’t trust women, and I had few female friends. I was a mess.

At some point, though, I made a conscious decision to take all the energy I was using to reject women around me to start embracing them instead, even if it didn’t feel natural at first. I cannot possibly express how helpful this has been in my life. Acknowledging other women’s attractiveness, and reaching out to get to know women I would have previously scoffed at, has been a bonanza for me. I’ve become more secure in my own looks, I’ve become more secure in my marriage, I’ve made absolutely amazing friends, and I’ve learned a million makeup and clothing tips. Let’s be clear: it’s not that my immediate thoughts have changed 100 percent. Sometimes when I see a gorgeous woman at a party I still have a knee-jerk reaction: “Look how short that skirt is, come on now!” But instead of spending the party seething—“How dare she dress sexually at a party!?”—I walk up to her and introduce myself. I make small talk. Essentially, I force myself to confront myself. I’m not suggesting that pretty women at parties just exist for me to further my emotional well-being, but where’s the harm in furthering myself while making small talk, something we’re supposed to do at parties? Sometimes the woman is awesome and we click; sometimes we don’t. Either way, she’s a human being, and no longer just a representation of my failings and my sausage-like legs. She doesn’t deserve that bullshit, and I have too much to do to fill my spirit with hate.

FUN FACT ABOUT LOS ANGELES

In Los Angeles, porn actresses are just everywhere, and they are some of the most fun and interesting women to talk to, women I would have missed out on if I were still in hate mode. They are naked and sexy for a living, and they also have hilarious stories about scenes gone wrong, lovely stories about relationships, and horrifying stories about how people talk to them. Get to know a porn star if you can.

Now, with all this I’ve been talking about times when the hate is coming from you; this equanimity stuff can be harder to pull off when the hate is coming at you. When confronted with systemic hate or ignorance that makes my blood boil, as much as I may disagree with the person spouting that hate, I’ve found it helpful to do a few things. First, I try to understand what underlies that person’s beliefs. You may learn that the Joe (or Josephine) spouting racist stuff online is just someone who grew up in a fairly homogenized town and is afraid of change. That doesn’t excuse the racism, of course, but it does explain a bit where he’s coming from. Let your emotions shift from hate, which can leave you powerless, to pity and sadness, because there is power there for you. Next, I ask myself what my hatred of that racist person accomplishes. Does it change her views? Does it eradicate racism? Nope. Instead of spending your energy on hate, spend it on a charity or organization that you believe injects good into the world. Spend that energy volunteering, or marching, or spreading factual information; if you’re a writer, spend it on creating characters that push people’s perceptions of what “those kinds of people” are like. When you cancel out your hate by doing something productive, not only will your energy be better spent, but you’ll get to witness how your positive injections can counteract those toxic negatives. There will always be something terrible happening in the world, unfortunately, and your hatred will not make it go away. So when you feel hate bubbling up, first take a look within yourself to see if there’s anything you can address inside to fight the hate. If not, take a look in a more positive direction to see if that doesn’t help. (Note: I am aware that as a white woman, I don’t get to tell anyone how to react to racism. There are mere suggestions for reframing terrible things.)

Weaknesses We Cannot Change

As I said back at the beginning of this chapter, there are two types of weaknesses: those we can adjust and therefore could improve, and those we can’t adjust and therefore should protect. What’s the difference? Great question. I’m still trying to work that out myself, and there are no real set-in-stone rules about this, but for now we’re talking about maladaptive habits that you’ve learned over time (changeable) versus lifelong personality traits (unchangeable). We could also consider the weaknesses you cannot change as actually weaknesses you will not change—but it’s a moot point. More important than the difference between the two is learning how to fit the weaknesses you aren’t actively working to change into the beautiful puzzle that is you.

Step one of this puzzle-fitting concerns how you classify yourself in relation to those unchangeable weaknesses. Think about it this way: Superman’s weakness is Kryptonite, right? And yet, he doesn’t call himself Kryptonite Man. Well, you may say, how stupid would that be? You’d just be advertising your weak points to strangers. And yet, so many of us define ourselves by our weaknesses rather than by our superpowers. In fact, many of us walk around weakness first, apologizing for ourselves right out of the gate.

I’ve met people who, within the first few seconds of being introduced, will tell me they’re bipolar, or OCD, or fat, or alcoholic—and when I’ve asked them why that information comes with their introduction, they’ll say, “I just don’t like to be fake,” or “I want you to know what you’re dealing with.” But leading with what you consider to be your faults isn’t being more honest—it’s just showing your “weak” hand, or shoving your complex identity into the weakness cubbyhole. Conversely, protecting what you consider to be your faults isn’t being fake—it’s simply opting not to promote your faults to headliner status. We all contain positive and negative qualities; the negative ones don’t deserve any more attention than the positive ones. When we advertise our faults first, we usually do it in a bid to test others, to see if they’ll be willing to stick by us even though we’re problematic, or to give them an out before we get too attached. But this is not how a Super You operates. The goal here is to be accepting and accommodating and gentle to our weaknesses—and not to deem them our most defining personality traits.

Let’s discuss a few common unchangeable weaknesses and how a Super You can best protect them.

Weaknesses We Cannot Change: Being a Control Freak/Wanting to Feel Needed

I put these two qualities together because for me, personally, they are connected. They may not be connected for all of you, but I’ve yet to meet anyone who struggles with one and not the other. As I mentioned in Chapter 3, I’ve been a control freak for most of my life. I’ve run a stand-up show in Los Angeles for the past five years, and everyone knows that the show always starts on time. Even when I was a teenage social outcast, my piercings and tendency to wear shirts that said ENJOY SATAN were my attempts to control how people felt about me—maybe you didn’t like me, but you were going to not like me for the reasons I chose, not for the reasons you chose.

So what can we control freaks do? I don’t want to change my control freak nature, because it serves me incredibly well in my work. I just want to use it only when necessary, and keep it safely tucked inside me the rest of the time. Basically, I treat my control freak nature as Daenerys Targaryen’s dragons—I love them and am proud of them, but I realize that they should be unleashed only on special occasions. (That was a Game of Thrones reference.) So in situations where it wouldn’t be appropriate to unleash the dragons, like planning a social outing or dealing with plumbers in my house, I purposely bite my tongue. I’m good at planning trips for movies and dinner, but that doesn’t mean other people aren’t also. Whenever I feel like I want to step in and take over, I repeat, silently to myself, “There are a million good ways to do something.” If things go poorly, that’s because things sometimes go poorly—it isn’t proof that your way would have been better. Besides, my friends all remember much more the time we walked two miles to a restaurant that was closed than the times we had an easy, successful brunch. I wish I had a better trick to offer you, but honestly, forcing myself just to be quiet and let other people take over has been the best technique I have for this. By accepting the plan that comes together, I end up enjoying it just as much, or even more, because it isn’t my sole responsibility.

Weaknesses We Cannot Change: Needing to Feel Needed

Now let’s talk about how we handle being a control freak in a relationship when we really just want to feel needed. (We’ll talk more about relationships in chapter 10.) For now, suffice it to say that when I yearned to make myself indispensable to the men I dated, I sought out men who already seemed like they were barely making it out of the house with matching shoes on. Some of the more villainous men that my Super You faced exploited this particular weakness in me, getting me to basically run their lives, and for a time it was a gross but mutually beneficial agreement. He got a maid/mother, I got a guarantee that he would stick around. After getting myself a good therapist, I gained the strength (to be honest, I was faking the strength at first) to start dating a man who was headstrong and fairly driven. He didn’t need me to pick him up or make him dinner—he was willing to do all that—and it terrified me. I was constantly afraid that he’d leave me, so I responded by inserting myself into his day-to-day functioning as much as I could, trying to stake a claim in this territory. It was sad to behold. Slowly I realized that this quality in myself, this need to feel needed, was only hurting Super Me. It wasn’t bringing me anything helpful: the men still left me, or we just settled into the ugly grooves of an unhappy couple that doesn’t find joy in each other.

GET TO KNOW EMILY’S CONTROL FREAKNESS

My control freakness, to the best of my self-exploration, isn’t about thinking I’m always right—it’s more of a fun cocktail of some of the darker corners of my personality. Some of this has been covered in chapter 3, but there’s more ickiness to behold! First, I have some trust issues. It takes a lot for me to trust other people. If I’m working with you in a professional capacity and if I don’t know you well, I’ll probably assume you can’t be trusted with complex tasks. This has both served me well and made me incredibly overworked. Also, as previously mentioned, I like feeling needed. Especially in personal relationships. In some ways, this is not as much a weakness as a human quality: as social beings, we all want to feel needed. For some, however, there is comfort in the idea that if you do literally everything for a friend or a boss or a romantic partner, you’ll in effect be indispensable, and others won’t leave you. You’ll be necessary, like oxygen! But please hear me now, dear reader: in relationships, each person should function as vitamins for the other person, not oxygen. It took me years to realize that it’s actually much more romantic to have someone stick around because he wants to be with me, rather than because he has to or he won’t be able to pay bills. Basically, since I didn’t consider myself worthy of someone’s love, friendship, or attention, I thought if I made myself useful the relationship would last longer. Beyond my need to feel needed, I also have a lovely martyr complex going on, and it goes like this: if I do everything, then I’m the most put-upon person around, and I can throw that back in your face when you question me. Perfection can’t possibly be expected from someone who is taking care of literally everything, can it?

I made a vow that, from then on, any guy I dated would have to function completely on his own without me. I forced myself to stop doing things for the men I was interested in, even if it was extremely hard for me. I continually told myself that, if he left me for not helping him do laundry, he was doing me a favor. I also did some work within myself on what I really got out of relationships, and realized that the perfectly normal need to feel needed could be met outside of romantic relationships. So I started volunteering with organizations that did desperately need me (or anyone, really) in order to keep functioning. I started applying my need to be needed to myself. And once I got into a healthy relationship, I let it be okay that every once in a while he needed my help with something. I even allowed myself to need him too. All of these things helped to tame the dragons. I couldn’t have achieved this without working on myself, which included forcing myself to stop doing things the way I always had. There’s no magic to this. It’s just effort and exploration.

Weaknesses We Cannot Change: Shyness/Introversion/Social Awkwardness

I don’t think of shyness as a quality to fix. The only reason to alter any quality is if it’s hampering your day-to-day life and bothering you. There’s a difference between people who are just shy in large groups and people who are riddled with anxiety at the thought of social interaction. And unfortunately for those of you who feel that anxiety, unless you’re a Buddhist monk with a lifetime vow of silence, being social is a part of all our lives. Plus, I think shyness has been demonized enough in our society, so I’m not adding to that chorus whatsoever. There’s a fantastic book called Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking by Susan Cain that addresses the value of being shy; I highly recommend it if this topic speaks to you. I also recommend it because I’m not going to get too in-depth on introversion and shyness here—I’m just covering the basics.

I happen to know the secret to being outgoing at parties, and I’m going to get in trouble for revealing it: most of us are faking it. An “extrovert” is someone who derives energy from social interactions. That is definitely not the case with me—nor is it the case with several of my outgoing friends. Social interactions exhaust me; I need time to myself afterward to recharge. A really intense party can even make me physically ill the next day, but that expense of energy is often worth it to me. To the outside world I may look like a social butterfly, but it takes effort, and sometimes it takes faking that effort. I sometimes feel awkward in conversations at parties, and I’m usually terrified I’ll have nothing to say, or that I’ll say something ridiculous. In fact, I hate weird silences among new acquaintances so much that I’ll usually keep a weird story on hand just to dole out at awkward moments.

So if going to parties exhausts you, please keep in mind that many of us feel the same—we just try to pretend otherwise. This is probably why Irish Goodbyes, or Ghosting, was invented—so we can leave without saying goodbye, since we can’t handle one awkward moment more.

But what do you do if your shyness and social awkwardness are keeping you from enjoying life? What do you do if you’ve been like this your whole life but wish things were different? How do we, as Super Yous, properly support and protect this vulnerable part of our nature, one that can take us down like Kryptonite? How do we strike a balance in pushing ourselves to grow a bit while still understanding this is just how we are? I think the best compromise lies in a duo-combo: finding a comfortable place to exist socially, from which we can regularly (or occasionally) push ourselves to try new tricks.

FUN FACTOID THAT CAN BE RANDOMLY BROUGHT UP DURING WEIRD SILENCES AT MOST PARTIES

Wonder Woman was created by an American psychologist named William Moulton Marston who also invented components of the modern-day polygraph test. One of Wonder Woman’s primary weapons is the Lasso of Truth. Hmmm . . . Also, he based the character on two women: his wife, and the woman he and his wife had a romantic relationship with. Hot stuff!

Shyness Tip 1: Becoming More Comfortable in Social Spaces

Finding a comfortable place to exist socially simply means recognizing ways that you’re already social that aren’t uncomfortable for you. This could include anything as small as going to a crowded café and sitting among the people for a few hours. It could mean hanging out with people one-on-one, or planning your own event with just the people you aren’t weirded out by. It could mean movie outings, where the small talk is (hopefully) limited to just before and after the movie. It could mean researching things you’re passionate about and finding where people who share your passion gather in your town. It could also mean being incredibly social in an online setting full of like-minded people—with a caveat: I caution you about subsisting solely on interaction where you don’t share the same space with your, shall we say, interacteur. You may not think the people in your real life get you at all, and maybe they don’t, but spending too much time socializing online only makes you less capable of socializing offline.

In my early teenage years in the early nineties I did all of my dating exclusively online, on Internet bulletin boards. Bulletin boards functioned like articles on a website, basically. Someone would post a paragraph-long post about a topic, and then everyone would respond in individual notes that cascaded from the original post. There were also chat rooms where groups of people could all type at each other at the same time. That’s all we had back then, folks, but at the time it served me well. When online, I was divorced from my physical form, which I hated and was convinced everyone else hated, so I blossomed into a bit of a femme fatale on the Nine Inch Nails BBs (bulletin boards). I was witty, I was funny, I was cool, and I was bold. And, thanks to the nascent technology (modems were super slow), rather than just stumbling around and blurting out weird stuff, I had time to think through my responses, successfully projecting into cyberspace the awesome girl I wished I were. (I’ve been plotting the Super You concept for years.) The problem was that I was only projecting and not making any moves to reach that projection. My online flirting just confirmed for me that this was something I could only do online, so instead of making me wittier in person with the guys at my high school, it drove me further into a little self-doubting shell. It took a bad experience of meeting an online boyfriend in real life—after weeks of typing how we’d definitely have sex and/or get engaged, we were both sucked into the black hole awkwardness of it all and barely spoke—to firm up my decision that I’d rather take my chances with the guys that I could talk to in person.

Shyness Tip 2: Pushing Yourself Socially

Which brings us to an important part of finding a comfortable place for your social life: pushing yourself socially just an eensy bit every now and then. We do this by trying new behaviors, faking our proficiency if we have to. This might involve taking a class with strangers, where you’re forced to interact with new people, but you don’t have to worry about embarrassing yourself with anyone you know. Or you could take a chance asking a new friend to hang out one-on-one, something that’s both exhilarating and a little bit scary. Pushing yourself could involve, if you can believe it, volunteering. At the place where I currently volunteer, an animal shelter, I interact with a wonderful mix of older men and women and teenage girls. Previously I’d never have thought I could make more than two minutes of small talk with any of them, but instead we gossip about the cats for hours on end, treating them as our very own soap opera. It’s been really eye-opening for me to find a comfortable place, socially, in an environment that I didn’t think could yield such a thing.

Now, some of the new things you’ll try might feel a little like fakery at first. As I mentioned earlier, fakery is a part of many people’s social lives—not necessarily to their detriment, and often to their advantage. Consider: if Superman were protecting himself, he probably wouldn’t walk into a party going, “What’s up guys? Hope there’s no Kryptonite here. Where’s the cheese plate?” We can think about shyness or social awkwardness similarly. If you’re shy, when you arrive at a party you can enter as quietly as you like, but be sure to greet the first person you know with eye contact and a firm handshake. There’s no need to announce that you’re socially awkward—that can just ratchet up the awkwardness. If there’s a lull in conversation, don’t feel the need to jump in immediately, and don’t feel weird about it—just let it sit for a moment. And it’s okay to people watch if you’re standing alone. Treat your conversations at parties as crop dusting: get in, sprinkle some socialness, and then get out of there. And note, while I can cheerily pop off advice like that, I’m personally really bad at social crop dusting—I get way too in there. And while I don’t mind having intense conversations at parties, it would be nice to have another option. So, make a little conversation, and when it runs out, have a great, preplanned parting line—“Well, it was nice to talk to you. I’m going to go check out the snack bar/bar/bathroom/inside of the house”—and then gracefully exit. The great thing about this technique is you can keep moving, have several small conversations, hightail it out of there if you’re feeling uncomfortable, and still look like a social butterfly!

This combination of both finding comfortable spaces and pushing yourself slightly is a great way to keep true to who you are—which can be as awkward or weird as you wanna be—while not handicapping yourself in public. Because we all have to exist in public.

Weaknesses We Cannot Change: Impostor Syndrome

A close cousin to negative self-talk, Impostor Syndrome is a bit more specific and harder to battle, and, if my anecdotal research among successful friends is to be believed, it affects women more than men. It’s the belief that, no matter what you accomplish, you still expect to be uncovered as a fraud eventually and sent back down to the minor leagues where you belong. You never internalize your accomplishments as your own doing, instead attributing the success to outside factors like luck (“I just happened to be in the right place at the right time!”), people being nice to you (“They gave me this award because they felt sorry for me not having any awards”), or faking your way through it (“I can’t believe I got all that done; I don’t know what I’m doing!”). Now, as you know, I’m a big fan of faking confidence or skills until you can grow into them as your own. My argument is that performing the actions of a confident person yields the same result. The disconnect people with Impostor Syndrome have is that, though they’re indeed performing the actions of a confident person, they’re never able to realize they’re actually competent. And that’s the problem. Faking it is supposed to be a temporary phase, but a lot of us don’t know how to stop faking and start existing—or, we don’t believe we deserve that existence.

I suffer from this a bit personally. I started out my career in a very specific field, therapy; I was highly trained, and I felt pretty confident. My education was the buoy I clung to when applying for jobs, my proof that I knew what I was doing. I framed that proof and hung it on my wall. Then I stopped being a therapist and started writing and producing comedy shows, where there are no papers to frame and display to help legitimize what you do. In the first few email pitches I sent to editors asking to write for their sites, I felt apologetic for even disturbing them. “I am not a real writer,” I’d think before hitting SEND, “and I’m taking them away from the real writers emailing them.” But I sent them anyway, and when I got positive responses back I was amazed and astounded. Years later—years filled with rejections and successes—I have learned this important lesson: no one really knows what he or she is doing. The difference between the people who go for it and the people who don’t? The people who go for it just ignore the fact that they don’t know what they’re doing.

A QUICK RANT ABOUT SUCCESS

I could go into a long rant here about how women are still expected not to make too much of a fuss in their respective fields, and how research has shown that even very successful women sometimes attribute their success to ridiculous things like “luck” or “supportive coworkers” or “magic”—but I’ll try not to yell for too long. Whereas men are often raised with the idea that everything they do is golden, women are often raised with the idea that they’d better not let on that anything they do is golden, lest they be seen as pushy braggart bitches. Plus, sometimes we fear that if we don’t do our work perfectly, we’ll be letting our gender down—not to mention confirming for everyone else what we’ve known from the start: we’re not cut out for this. So we stay silent and under the radar. It’s a lose-lose that a lot of us internalize for various reasons, be they familial or cultural. Fortunately, I’m convinced that mindset isn’t going to stick around.

So pull up a chair and let me tell you a few things. It’s okay for you to take up space. It’s okay for you to put yourself out there requesting work if you feel you can do it adequately. It’s okay for you to get rejected. It’s okay for you to succeed and be happy about that success. It’s also okay for you to fail. Failing doesn’t mean you’re a failure, and it certainly doesn’t mean that women are failures. And besides, come tomorrow, you’ll probably have another success to add to your wall.

There’s no real cure for Impostor Syndrome other than recognizing it in yourself and calling it out. Once a year or so I’ll look back at what I’ve done that year, job-wise, and ask myself what skills I’ve gained from all that work. I force myself to take stock of what I’ve internalized from each job I’ve done, and I write it down in my notebook so I can refer to it when I’m feeling unsure.

We can also just keep at it. I was in a room with a bunch of writers/performers recently, male and female, all of us pitching ideas for a project. The goal of such a gathering is essentially to make the other people laugh. I was somewhat intimidated and didn’t speak much, which you probably know by now is hard for me. But a male friend of mine spoke up quite a bit, with ideas that sometimes worked and sometimes didn’t. Afterward I pulled him aside to ask how he had the confidence to pitch so easily. “That one joke got, like, nothing!” I said, half teasing him to hide my genuine interest in his confidence. “Sure,” he responded, “they didn’t like that one. But I knew they’d like something eventually.”

Oh. So that’s what that looks like.

Weaknesses We Cannot Change: Mental Illness

It feels weird to put mental illness in the category of unchangeable weaknesses that must be protected and managed, but I wasn’t sure where else to put it.

Of course, in my professional life I’ve seen mental illness in hundreds of forms, and, as is likely the case for many therapists, my personal life has had its share as well. Indeed, my impetus for becoming a therapist was in part growing up with family members who suffered mightily from various disorders. So let me speak to you now with my therapist hat on: if you believe you are suffering from mental illness and have not yet sought out treatment, this book is not the answer for you yet. Working on your self-esteem and becoming your Super You is less of a priority than getting your thoughts and moods more stabilized. Depression, severe anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, any disorder with psychotic features, and personality disorders are extremely taxing and disruptive; if you suffer from any of those, you’ll want your symptoms managed a bit before you try to work on your self-esteem. Besides, dealing with active and oppressive mental illness while trying to work on your self-esteem is like Spiderman trying to stop jaywalkers while Green Goblin is terrorizing the city. First Spiderman must prioritize dealing with Green Goblin; he can deal with the jaywalkers later.

Of course, we don’t always realize we have a Green Goblin situation going on. If you’re finding that nothing in this book is working to help you feel better, that you’re having trouble with day-to-day functions and find yourself feeling off without any real rationale, I highly encourage you to seek treatment. Find a good therapist, discuss options for medication if that feels appropriate, and involve your closest friends and family. The National Institute of Mental Health has a pretty good website with information about disorders and how to get help. Please be aware that looking up information on mental illness can sometimes lead you to believe that you have every disorder, so do research with a grain of salt, and find yourself a therapist that you feel comfortable with. It takes a group effort to treat mental illness, and that effort involves you reaching out for support, taking steps forward, falling backward—as is pretty much inevitable—and then getting up and doing it all over again.

The best part is, when you’ve reached a point where you’re feeling stable, and are no longer in day-to-day crisis, your Super You will be waiting for you.

Amazingly, there are some incredibly positive qualities that can come from mental illness, and I don’t just mean how paranoia can keep us safe from ne’er-do-wells, though it can. Depression can help us to slow down and ruminate, staying for a while in our emotions. (Obviously, for such sufferers this can become too much of a good thing.) Depressed people have been found to be more adept at analytical thinking, especially examining larger problems and breaking them down into smaller parts. Anxiety and OCD tendencies are a fantastic aid in life organization and are one of the reasons we can keep on top of many tasks at once, getting everything in place just in time for curtain call.

MENTAL ILLNESS IN COMIC BOOKS: AN APOLOGY

As you can probably guess, in most comic books mental illness has not been treated with sensitivity or even with basic understanding. Because they’re so full of secret identities, comic books often give characters “multiple personality disorder”—something we now call dissociative identity disorder, which happens to be very rare.

One example of this is Jack Ryder, a character in the Batman universe, who is a political pundit by day but by night dresses up as the Joker, calls himself the Creeper, and injects himself with drugs to make him stronger. Unfortunately the drugs also make him psychotic, and he starts believing he and the Creeper are two different people.

Erica Fortune, also known as Spellbinder, has a superpower of traveling through different dimensions. At some point the stress of experiencing other dimensions makes her lose her marbles, and when she returns to our dimension she kills her family because she’s insane.

I’ve come to see how anxious and intrusive thoughts—like how I make deals with myself that I’ll stop fretting about something if “X” happens; I told you about that, right?—are part of a continuum of behaviors.

For me, the key was learning that my anxious thoughts don’t mean that I’m somehow more observant about the world around me, or god forbid, psychic. I do my best to accept the gift of being detail-oriented while dismissing the self-beliefs that often come with anxious thoughts. In the same way, you can recast your weaknesses as superpowers for your Super You—like how Spiderman’s superpowers mean that it’s somewhat hard for him to date girls like a regular teenager. Again, I don’t mean to downplay or trivialize mental illness, and it’s not that I wouldn’t love to lose the intrusive thoughts that keep me awake at 4:00 AM about how I’m not going to enough museums—even at the cost of my attention to detail. What I do mean is, in assessing the parts of ourselves we don’t think we can change, we can work to recontextualize qualities we’ve up until now seen as weaknesses.

To help with that, here are some tips for people coping with mental illness.

Mental Illness Tip 1: Getting Treatment

To help destigmatize mental illness a bit, let’s instead think of it as asthma. If you have asthma, you might take a daily pill or inhaler and carry an acute inhaler to use as needed; you might also see a doctor every few months. And that makes sense, right? If you have an ailment that calls for some kind of attention, taking care of it makes sense. So, whatever your disorder may be, make active maintenance and treatment of it part of your routine, whether that means medication, a semi-regular therapist, or a support group. Make it like brushing your teeth.

Mental Illness Tip 2: Knowing Your Triggers

If you have asthma and you know that hot weather can set off attacks, then when it’s hot out you know to be ready. Or if running for a train makes you grab for your inhaler, then you’ll want to leave yourself plenty of time to get to the station. I’ll bet there are triggers that can similarly cause your disorder to flare up, be they certain times of year, certain situations, or certain people who can bring it on. Take stock of yourself: list your triggers so you know what you’re working with.

Mental Illness Tip 3: Having Action Plans Ready

Once you know what your triggers are, you can set about determining great plans for when they kick in. If I feel a panic attack coming on, I like to write down all fifty states to distract and calm myself—and because I’ve planned this in advance, I know what to turn to when I need it. If you feel the big bad sads creeping up on you, have DVDs at the ready that always comfort and energize you. And when you need someone, know which people you can call for support.

It’s important to remember: even though mental illness can happen to you, it isn’t you. It’s part of you, absolutely, but it isn’t all you are. It’s simply a chronic condition, which calls for regular treatment—rather than an acute condition like an infection, which requires just one dose of treatment. So, whatever your situation, know what your particular deal is, and know what to do with it when it arrives.

Your weaknesses are yours, whatever you decide to do with them. Own them, get to know them, figure out which ones you can change and which ones you’ll keep around out of necessity or affection. We’ve gone too long keeping our own darkness in the dark—it’s time to bring our weaknesses to the light, noting their importance without making them the most important thing about us.