NO JOAN OF ARC

My parents were married for seventeen years before they split. During that time, my Armenian and Roma families tolerated each other, but barely. Though not openly hostile, each side secretly regarded itself superior to the other, more cultured and sophisticated. Ironically, love of superstition was the biggest thing they had in common.

The Armenians spit over their shoulders and knocked on wood, while the Romani crossed themselves when yawning, to prevent evil spirits from entering their bodies, and poured salt around the foundations of their houses to keep them out. Every time Mom and I got on the train from Kirovakan, her hometown, to go back to Moscow, Aunt Siranoosh splashed water from a ceramic bowl onto the platform to ensure a safe journey.

At wakes, my Romani relatives poured vodka shots for the deceased so they would not feel parched on their way to Heaven, and my Armenian relatives covered the mirrors with swaths of black cloth so the dead wouldn’t get lost by walking through them into the realm of the living and become ghosts.

In each culture, nearly everything was construed as a sign. Back in Moscow, if Dad missed a turn on the way to a party, he’d turn around and drive home. No one sat at the table corners unless they didn’t want to ever get married. If you dropped a spoon on the floor, a woman would come calling soon; a knife signified a man; and if it happened to be a fork, the powers to be were not 100 percent sure on the gender. The signs are endless and move inside me like mice in a wheat field. To this day, I catch myself skimming tea bubbles off the top of a steaming cup and dabbing them on the crown of my head in hopes of acquiring a large sum of money.

According to Russian Roma legend, the period between December 21 and January 14 is when spirits come down (or up, depending on your viewpoint) to walk the earth in celebration of the winter solstice. If you dream of discussing Macbeth’s foolish ambitions with Shakespeare himself, your chances of success increase greatly during these magical days.

The season is marked by ceremonies to divine, cleanse, and renew. The enthusiasm with which the Roma carry out these acts can be contagious, especially if there’s a chance of seeing what your future husband might look like.

At well past midnight, Dad, Olga, and I sat in a tight circle around the table. A candle burned on top of the kitchen counter, next to a sink full of dirty dishes and a bottle of Jack Daniel’s. In my opinion, it conveyed great disrespect to summon spirits amidst the pungent smell of fried carp and the slowly gyrating curls of cigarette smoke coming from my stepmother’s lips. But I did not voice these thoughts, preferring to watch Dad watch Olga with great interest.

A piece of white poster board lay on the table. In the middle, all the letters of the Russian alphabet were arranged in a wide circle. Olga placed a small white plate marked with a single arrow at one edge in the center of the circle. “Porcelain,” she said. “The purer the material, the better the reception.”

I’d seen the plate before. It was one of the few items Dad had brought with him from Russia, where he had kept it locked away. Any object used in divination was off-limits to kids. As a little girl I once made the mistake of playing with Esmeralda’s personal tarot deck. When she found me gently lowering the king of hearts onto the roof of my newly built house of cards, she moaned, “How could this have happened?” as if I’d stolen bonbons out of the special Richart chocolate box she opened only for dates with the most “marriage” potential.

I gathered the cards. “I was careful. Didn’t even bend them, see?”

With a sigh, Esmeralda kneeled on the floor next to me. “They won’t work anymore, sweetie. I’ll have to buy a new deck.”

“I broke them?”

“Cards are part good, part bad, God and Devil all in one. Kinda like grown-ups. They need both in order to work, but kids are all good, you see? So when you played with the cards, they lost their Devil.”

Esmeralda’s cards, after I’d ruined them

No one was allowed to touch Dad’s plate, kid or adult. And now Olga pawed it while discussing its quality. As I got ready to say something wicked, she closed her eyes, touched her fingertips to the plate’s rim, and began to chant along with my dad.

I knew what was coming, had seen this done numerous times before. It was kind of like using a Ouija board without having to pay $19.99 for the fancy lettering. But to my family, it wasn’t a game.

When I was eleven, I’d overheard my parents and some of their friends channeling one night in our Moscow kitchen. I didn’t see spirits, only Dad reading an incantation from a tattered book with a black leather cover. It had belonged to Baba Varya. At that age I knew her only as a vedma, so seeing my father use her book terrified me.

I used to love driving to the outskirts of Moscow with my mother to visit Agrefina or watch some other ancient Russian crone predict our future using stagnant water. Mom nursed not an ounce of skepticism for these peculiar practices, as if she were taking in a doctor’s diagnosis. Even our own priest discussed the future with a fortune-teller’s poise. I grew up with God and the Devil and every other idol in between at my doorstep. Opening that door was just a formality. Every December I participated in various divination ceremonies, and on Christmas Eve, Zhanna and I made sure to place saucers of springwater under our beds, hoping to dream about our future husbands.

At Dad and Olga’s table, my heart thrashed like a cat in a sack, with a mixture of anticipation and fear. Channeling, to me, has always been like deep-cave diving: a daredevil sport.

The air around my shoulders wavered. Chills ran up and down my arms. I scooted forward in my seat just a touch.

Dad raised his head, hair shining in the abruptly frenzied candlelight. He opened his eyes and looked up to the ceiling. “Spirit, I thank you for responding. I am Valerio, and I do not bind you by any act of artifice or vengeance. Will you choose to confer?”

The plate slid to “Yes.” Olga’s fingers barely touched it.

My pulse drummed inside my ears.

“Thank you,” Dad continued, exchanging a satisfied smile with Olga. “What is your name?”

“Avadata,” the plate spelled out.

A quarter of an hour later, we knew a lot about Avadata, although it did not make me any less scared. She had been born in 1888, but would reveal neither where nor any of the details of her death. According to her, the afterlife consisted of seven levels, number seven being Heaven and number one, Hell. A soul worked its way up by aiding the living and being generally virtuous. Presently, Avadata resided on level three, which, she informed us, was “a dastardly place.” But she wished to raise her status and so had been searching for ways to increase her chances. She adored cats, and often took possession of people fond of liquor and opium, a habit she had been trying to break herself of.

I glanced nervously at the half-empty whiskey bottle, then back at the plate, which was crawling to “No” in response to Olga’s question of whether she’d soon become a millionaire.

“Ask her something,” Dad said to me. “We don’t know how long this connection will last.”

“Like what?” I asked.

“Anything. How about your past life? You’re always asking me about it.”

I cleared my throat. “Ms. Avadata, could you tell me who I was in the past life … please?”

For a while, nothing happened. I began to think, with some relief, that perhaps Avadata had grown bored and left. But then—

“It’s moving,” Dad whispered, and leaned closer, stringing the letters into words as the plate slid around the circle. “1943. Le-nin-grad. Or-pha-nage 72. Head. Mis-tress.”

“How glamorous,” Olga said, clapping her hands.

I had hoped for Nefertiti, or at least Joan of Arc, but the headmistress of an orphanage?

“Maybe she’s making stuff up, like the way you do,” I suggested to Olga.

“No, it makes sense. That’s why you’re always bossing Roxy around. So cool, so serious, like a gendarme. I bet you wore your hair in a tight bun and everything. A whip and a ruler are in your blood, my girl.”

“How would you know? You’re not our mother.”

“Stop that,” Dad interrupted. “You’re acting like children. Concentrate or the spirit will feel the discord and leave.”

I shot Olga black looks as if she had had something to do with Avadata’s ridiculous claim.

“Ask another,” Olga said to me. “Ask who you’re going to marry. Chicken?”

My hands pulsed with the urge to hit her. Even if no real animosity marked her attitude, she had this annoying habit of always looking perky and amused at someone else’s expense. I had to keep reminding myself that she meant no harm. Or else I’d wind up giving her the opportunity to replace the rest of her teeth with gold nuggets.

“Don’t be a baby. Come on.”

“If you call me a baby one more time, Olga, I will cut off your hair and make a stuffed cat out of it.”

She roared with laughter. “So you’re not all spineless Armenian like your mother. You’ve got a temper after all. I was wondering where you were hiding it.”

“Don’t talk about my mother.”

“That, right there,” she said. “That’s your Roma fire, girl. Don’t keep it caged up.”

“I’m only half Gypsy. In case you haven’t noticed, we’re Americans now.”

“Darling, you’re no more American than pizza. Your father is Rom, and that makes you one, too, whether you like it or not. Be proud.”

Her words rang true, and I hated her for it. “It’s late,” I said, standing up, not caring about hurting even the spirit’s feelings anymore.

Olga pelted me with laughter like a skillful bully with a slingshot.

“Leave her be, woman,” Dad said.

Without waiting for a response, I stormed out of the kitchen.

That night, I lay wide-eyed and restless on the living-room pullout couch, seriously considering leaving my father’s house for good.

I wished Grandpa Andrei were there to talk sense into Dad.

Perhaps he’d remind him about all those times the band members got arrested in marketplaces because the police assumed that no Gypsy could resist the urge to read a palm when in public places.

Of course not all Soviets held these views.

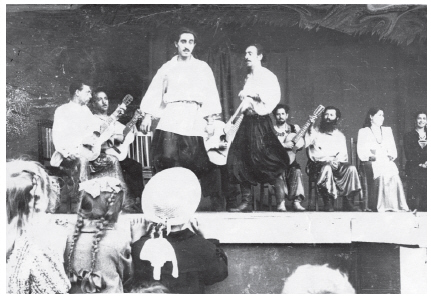

Russian kids watching one of Grandpa Andrei’s earliest shows, Kiev, 1939

During World War II, wounded soldiers often found refuge among the Gypsies. Many a time Romani aided the partisans by carrying messages between military posts across hostile territories; Roma mail became of much use. Romancy, Russian songs that were a vital element of Russian culture, were a fusion of Roma and Russian styles. Great writers like Tolstoy and Pushkin had been known to disappear with the caravans for weeks. Tolstoy mentions it in his writings more than once. Every time he feels dejected, it’s off to party with the Gypsies. Pushkin was enamored with their romanticism, their wildness, and their bond with nature, and even dedicated an entire narrative poem to them, The Gypsies.

The Gypsies in a boisterous throng,

through steppe of Bessarabia wander.

Their dingy camp is pitched along

The bank above the river yonder.

How free, how cheerful their tents lie

With tranquil dreams beneath the sky.

Between the wheels of carts half slung

With tapestries and threadbare rugs,

The meal is done, the bonfire’s blazing,

The horses in the field are grazing.

There were Soviets who proudly confessed to having “the blood” in their family tree, and there were those who clutched their purses as soon as the word “Gypsy” grazed their ears. According to my grandparents, the country had always been divided this way. But so were the Russian Roma.

Zhanna and I came across a group of Roma women once, right after Zhanna had turned fourteen. It was a beautiful spring day and we had decided to take the metro from my parents’ house to Esmeralda’s on the other side of town, which would give us a chance not only to people-watch but also to show off the new French denim vest Zhanna got on her birthday. At the Tretyakovskaya station we followed the midday crowd outside, where we were suddenly surrounded by a flock of women in colorful skirts. They were Roma, although their dialect, as they admired my gold earrings and Zhanna’s vest, sounded slightly different from the Rromanes my family spoke.

“Beautiful girl,” one of them addressed me. She wore a scarf that only partially covered a bruise on her neck. “I’m a famous Gypsy fortune-teller. Let me tell your fortune.” She accosted my hand and with one finger drew a circle in the middle of my palm. Next she pressed a pocket-size mirror into it. “You have five rubles? If we put it under the mirror you’ll see your future husband’s face.” From the corner of my eye I saw another young woman place an identical mirror in Zhanna’s palm, and I heard my fortune-teller tell Zhanna’s fortune-teller, in Rromanes, to hurry it up before the next train came.

“Do you know us?” Zhanna said with a kind smile.

“Yes, yes.” The woman extended her other hand. “I’ll only borrow the money.”

“We’re Andrei Kopylenko’s granddaughters.”

As soon as the women heard that, the mirrors returned to the pockets of their skirts and they let go of our hands.

“Devlo,” my fortune-teller exclaimed. “You Romani girls? We had no idea. Why didn’t you say so?”

We gave them money anyway, because we knew that most likely they had husbands back home who’d beat them if they didn’t return with enough earnings for alcohol and cigarettes. We’d also give the change in our pockets to the Roma kids begging near churches. We knew where the scratches and the bruises on their skinny arms came from.

I was so afraid that my father, like those women, would pigeonhole himself. I’d hoped that when we moved to America, we could avoid those kinds of assumptions about us, as long as my family behaved.

Only now, instead of moving away from the one thing that could hurtle us out to the fringes of society, he was preparing to announce it to the entire population of Los Angeles.