AT THE DELI

Months after I last saw Uncle Arsen and my cousins, Mom came home very late one night. I was waiting for her outside by the mailboxes, but knowing I’d get in trouble for snooping, I had hunkered down in a spot shy of the security lights. This way I could sneak back inside unnoticed.

She wasn’t alone as she stumbled out of a car—my uncle’s car. I didn’t know why she’d gone to see him; perhaps to make up? Or not. Walking together toward the building, they looked as irritated with each other as the last time. Mom swayed and Uncle caught her by the elbow and shoved her through the gate. They began to argue. I was too far away to discern their words, but knowing Mom, she was probably insulting him. Then she swung at him and lost her balance, nearly falling onto the metal gate’s decorative spear points. She caught herself in time, but when she straightened I saw a dark splotch on her left cheek. I forgot all about hiding, and when Uncle saw me shuffling toward them down the concrete walkway in my slippers, he jumped into his car and took off.

Back at our place I helped Mom onto her cot, fully dressed minus her pumps, and pulled a tissue from a box nearby. Next to us my sister lay sprawled over her blankets, mouth open over a round spot of drool on her pillow. I covered Mom with a sheet. The smell of vodka and blood invaded my nostrils. I’d never be able to forget this combination.

Mom’s lids shuddered. “You’re so strong. I never worry about you.”

“That’s great, Mom.” I wanted to clean off the blood, but I was too scared to see it spread to the edges of the tissue like a living thing, to have the scent cling to me.

“Not worried about Roxy, either,” she mumbled heavily. “I wish I was her. Too young to understand anything.”

But I think she was wrong about that.

* * *

When we first got kicked out of Uncle Arsen’s house, I wrote a note on the back of the phone directory I found under the kitchen sink of our new apartment:

We are a broken bottle, jagged edges rising from what used to be whole.

I was not really sure why I didn’t write those lines in my journal. After I finished, I ripped out the scrap of paper and flushed it down the toilet. When Roxy walked in on me hovering over the toilet bowl as if I held a grudge against the L.A. sewer system, she wrapped her fingers around my wrist. “Why are you always so sad?” she asked. “Makes me wanna be sad, too.” I didn’t answer, as had become my habit. I must’ve made her feel invisible countless times, so involved was I in my own world. An older me often thinks about the inaccuracy of that note. I still had a family to preserve: my sister. Instead, we started to ever so slowly drift apart.

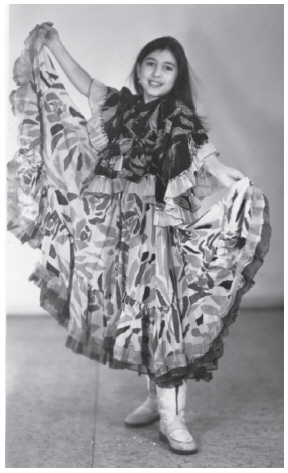

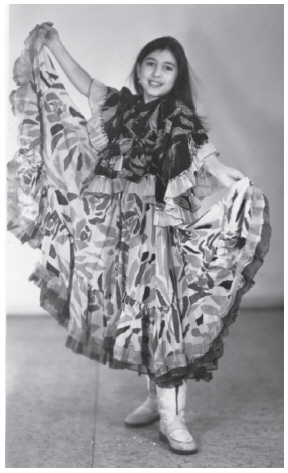

Roxy practicing for stardom in one of Mom’s altered costumes

* * *

In our apartment, life was a rotten potato lost between the fridge and the counter. No matter where you went, the stink followed. But at Dad’s, too much excitement and novelty made our troubles invisible. Olga proved a riveting distraction, a mischievous sprite out to grab your soul. I understood why Roxy shot down the stairs like an arrow every time Dad came to pick us up, but I was still avoiding his house as much as possible.

“School is out for the summer and you have plenty of free time. Don’t you want to spend it with your father?” Olga would say every time I tried to get out of visiting. A question that could be answered in only one way. It wasn’t just Olga’s presence; after that first channeling session, she’d been trying on “nice.” Mostly my reluctance had to do with the habitual way Dad and Olga used me, like my mother had, as their interpreter. The ironic part was that they didn’t really ask but embarrassed me until I volunteered.

At a doctor’s office once, my father got down on the floor and started pumping push-ups to convince the man that he had the heart of a lion.

“Quit acting like an imbecile.” Olga hunched over him, shouting.

The doctor clutched his file with both hands and retreated into the corner.

Dad jumped to his feet. “You call me names in front of the good doctor?”

“I’ll call you whatever I want. We’re married!”

“They’re always this loud,” I said, in case the poor guy wished to take notes. “Eastern Europeans always sound like they’re arguing.”

“So they’re not?” he asked quietly.

“If you want to stay married, you’ll get the hell out,” Dad was saying.

Olga yanked open the door. Some of the nurses had gathered outside, pretending not to appear curious or worried. Dad and Olga hollered things about each other’s mothers loud enough to make me want to hide in the cupboard under the sink until Olga stormed out.

Our first trip to Santa Monica, Dad drove up to a man on the corner of Highland and Sunset to ask for directions. He rolled down the window and said, “Excooze me, sir. You know vay to bitch?” At a drive-through, Roxy or I would beg to order, to stop Dad from saying things that could land him in jail. Things like “I hav six penises of change to that dollar.”

Only one thing granted me the get-out-of-jail-free card: getting my period. As long as I blamed “female problems” for not coming over, Dad left me alone; he had great fears of anything concerning childbirth, menstrual blood, and especially tampons. In Romani culture, men don’t usually participate in female matters. A woman on her period is unclean and to be avoided. Even in marriage, the wife is encouraged to keep her menstrual and childbirth issues to herself. Roxy and I would work out a story, and once there, she’d go into detail describing the cramps rendering me bed-bound.

One day Olga called and pleaded with me to come by. She wouldn’t say why over the phone, but it sounded serious.

“Oh! You’re in love,” Olga said almost as soon as I’d stepped through the front door.

“What?” I said. “Don’t be crazy.”

I began to defend myself against her silliness when I noticed another person in her kitchen, and I went silent; I had too much dignity to discuss this in front of a stranger in a pink velour jumpsuit. Olga’s guest was roundish, with short red spiky hair and a rat face.

“So what do you need?” I asked, crossing my arms and avoiding eye contact with my stepmother.

Hands on hips, Olga clucked her tongue. “Oksana. You know I’ll find out one way or another. You can fool your father but not me. All I can say is that it better not be some pimple-faced gadjo.”

“Stay out of my business.”

Narrowing her eyes, Olga sat down beside the woman and put an arm around her shoulders. “Svetlana’s husband is cheating on her, so we need to go to the deli up on Highland.”

No other explanation was offered; Olga often assumed that other people read minds, too.

As if on cue, Svetlana pressed a napkin to her forehead, mopping sweat from under a shock of red bangs. Normally Romani women wear their hair long, but Svetlana had reinvented herself after leaving her first husband, a drunk from Siberia, for a sober Russian Jewish accountant.

“Oh, my Igor, my sweet Igoriok,” she moaned. “How could you do such a thing? Cheating! Damn your black soul. May your balls dry up into raisins, you bastard.”

As Svetlana continued her lament, Olga tried to comfort her with Twinkies. I felt for Svetlana, but more so for Igor.

“Oksana, please. Can’t you see how the poor woman suffers?”

“And how is this my fault?”

All of a sudden, Svetlana was on me, squeezing my hands. “Oksanochka, sweetheart, he must return to me,” she wailed.

“And I’m supposed to make that happen how?”

“The witch works at Giuseppe’s Deli,” Olga said.

“Ashley,” Svetlana said, looking like she’d tasted a rotten egg. “American.”

Olga patted her client on the shoulder. “Oksanochka, we need you to go inside and get one of her hairs.”

I pried my hands from Svetlana’s, slowly, so as not to disturb a woman who was clearly insane. “You want me to steal a hair.”

“Yes,” they said in unison.

“From a deli. With customers and meat and stuff.”

“Yes, yes, what’s the matter with you?” Olga said. “I need one of her hairs for my spell. That’s all I ask. I’m not an evil stepmother. I don’t make you scrub floors. This one simple thing is all I need from you.”

“If it’s so simple, why don’t you do it, then?”

Svetlana grabbed me again before I could protect myself. “Sweetie, she’ll suspect something if one of us goes. She probably knows what I look like. He’s my husband,” she moaned. “Please, I beg of you. Go in, buy a pound of roast beef, and on your way out, pluck one of the bitch’s hairs.”

I couldn’t stand the idea of assisting Olga in any way, but as Svetlana bawled, her makeup running, she looked at me with so much desperation that I could almost feel it wrap around me like cellophane.

We drove to the deli. As I swung out of the car, Svetlana squeezed my hand and kissed it. I turned around and walked to the store with downcast eyes.

* * *

Delis are cheerful. You come in and you’re instantly enveloped by bright lights and the aroma of cold cuts and fresh bread. Not the atmosphere in which to reach over the counter and snatch a handful of the clerk’s hair.

“What can I get you?” my unsuspecting victim asked. She was so thin, probably four of her could’ve fit into Svetlana’s velour pants.

And of course she wore a hairnet.

My brain scrambled for a solution, and I was beginning to lose feeling in my tongue. “I am supposed to buy roast beef,” I finally managed.

“How much?”

“Can you show it to me?”

Ashley blinked a set of fake eyelashes before leaning over the glass case and pointing. “That one right there.”

“The one on the left?”

“No, over there.”

I shook my head in embarrassment, which, at that point, was genuine. “Very sorry. Can you show me from here? If I buy the wrong one, my mother will beat me.”

It was a long shot, but it worked. The woman looked at me strangely, then walked around the counter and stood next to me jabbing her finger at the glass. “The one that says ‘roast beef,’ right here,” she said.

“I see it. Yes. So sorry. My reading is not so good.”

A thin blond hair beckoned from her upper sleeve. I played my “creepy foreigner without a sense of personal space” card and gave her arm a grateful squeeze. “You a good deli person.” And came away with my prize, closing my hand around it.

Ashley eyeballed me while she cut the roast beef and wrapped it. I left the deli, memorizing the location to make certain I’d never shop there again.

I jumped into the backseat of Olga’s car. The interior was a nebula of smoke and I coughed, rolling down the window.

“How did it go?” my stepmother asked.

I handed her the hair along with the roast beef, a little disgusted and ashamed at the same time.

“Did she see you?” She dropped the hair into a sandwich bag and handed it to Svetlana, who rolled it up carefully.

“Well, yes, she saw me. I was buying roast beef,” I said.

“Did she see you take the hair?”

“No. At least I don’t think so.”

“Good girl,” she said, and started the car.

Only, I didn’t feel so good, not just about violating that poor woman’s privacy and subjecting her to a bout of witchery but also because Olga was driving.

Her approach was generally to go straight and turn only when absolutely necessary. Red lights were meaningless blinks in the distance. She rarely paid attention, flying through intersections, dismissing the traffic as I screamed for her to watch out, our car passing others seconds before impact.

In the midst of this madness, Svetlana turned to me.

“Wasn’t she the scraggliest thing you’ve ever seen?” she said, giving me her best sour-candy face.

“I’d rather not talk right now,” I said, wrapping my fingers around the door handle.

Olga tossed me an annoyed glance, and then patted the other woman on the shoulder. “Svetlana, don’t bother my stepchild. She’s left her sense of humor at home.”

I was holding on to the door with one hand and gripping the seat belt in the other. Another red light, another heart palpitation.

Svetlana shrugged. “What did I say?”

It wasn’t what she had said but my feeling of helplessness in the face of Olga’s triumph. She gloated over how she’d gotten me to help her.

“Okay. I did what you guys asked, now let me out.”

“Why?” Svetlana said. “Because your stepmother has such a big heart? Because she’ll do anything to help people in need, people like me?”

“She didn’t do this, I did. What if I got caught?”

“Doing what?” Olga said, driving with one set of tires on Melrose Drive and the other on the curb. “If we were in Russia you’d never complain like this. Such disrespect for your father.”

“Jesus, can you watch the road, please.”

“So true,” Svetlana said. “Kids here are so spoiled.”

Olga agreed. “It’s because of Nora. Armenians dote on their children. Had she grown up in a real Romani household, she’d learn obedience, quick.”

I was used to Olga blaming the Armenian side for my every flaw, but I always believed my big mouth was a result of my Romani blood. I told her as much, at which point she stopped the car and let me out.

“I’m not done with you yet,” she said, leaning over Svetlana to glare at me.

“You should drive a flying carpet,” I said. “It’d be safer for everybody.”

She sped off, cursing the land I was born on, and I mumbled a little prayer for all of L.A.’s unsuspecting motorists and one skinny deli clerk.