EXOTIC

On the first day of my magnet classes, I came to school one hour early, excited to finally experience school the American way. I had plaited my hair into a neat French braid and put on a plain black sweater with a pair of jeans; there would be no fashion faux pas for me this time.

I took a seat in the very back, my stomach a tight ball, watching students come in laughing and joking with each other. No one paid attention to me, and I was grateful.

Cruz sauntered in, scanning the room until his eyes settled on me. He found a seat next to mine, dropped his backpack on the floor, and put an arm around my shoulders as if his presence there were a blessing from the Almighty.

“What are you doing here?” I said.

I was smiling, dammit.

Lately he had been spending several days a week at Dad’s house. That first time, he walked into our living room and his eyes immediately flew to the mantel. Above it hung a poster-size image of Grandpa’s entire troupe posing center stage for a publicity photo. Dad had framed it in cherrywood, which made it even more impressive.

The Andrei Kopylenko Gypsy ensemble, 1980. Grandma Ksenia is in the middle; Dad is to her right, holding the guitar; and Mom is on the floor, to the right

“Who’s that?” Cruz asked.

“My family.” I stared right back at him as he raised his eyebrows and crossed the room for a closer look.

“That looks like you, a few years older.”

“That’s my mom.” Patiently I waited for him to ask about the origin of the costumes.

My father walked in with a pipe in one hand and a rolled-up newspaper in the other, meaning he was on his way either into or out of the bathroom.

“Eh,” he exclaimed. “Beelo vremya kogda mi bili ochen znamenitimi Tziganyami (There was a time when we were very famous Gypsies).”

Cruz turned, eyebrows so high I thought they might fly right off his face any minute. “Ciganos? Gypsies?” he said, and when my father nodded, he turned back to the picture. “Awesome!”

My expectations of Cruz running at the first mention of anything Gypsy were kind of deflated. But that also got me thinking. Perhaps it was time to stop hiding and follow through on the message I chanted in front of my mirror.

The way Cruz reacted to the picture made my father even more affable, but I still expected him to wake up and realize he had opened the doors of his studio to a gadjo. While waiting for that moment to arrive, though, I utterly enjoyed listening to Cruz pretend to be a good student. He’d been playing guitar for more than ten years when Dad started teaching him the names of all the guitar parts.

During the first lesson, my father whipped out the flash cards he’d made himself.

“This note G,” he said, holding up the one with the appropriate sketch.

Cruz’s fingers hovered over the strings, lips moving silently, eyes determined to find that G string, as if he’d never seen one before. He bullshitted through that hour and kept coming back for more.

For his instructor’s sake, Cruz missed just the right number of chords and hand positions to appear in need of constant supervision. In essence, Cruz was making the lessons all about my father and his pride. Naturally he proved to be a quick learner, and Dad attributed this remarkable progress to his own brilliant teaching methods. I thought surely Dad would figure it out eventually, even if he missed the gadjo part. Or maybe Cruz would realize that he didn’t actually have to take lessons, that he said what he had said on that lawn only to prevent a massacre. But they got along so splendidly that neither seemed in a hurry to change things.

Olga was surprised at Dad’s behavior, but she had a ready explanation. “He treats that gadjo like an offspring,” she once said. “It’s just sad. Maybe I’ll do him a favor and give him a real son or two.”

In the ESL program, too afraid to reveal my Romani side, I had remained an Armenian, a face in a crowd of similar faces. But like Cruz, the American kids were different. The majority of them were uninformed of life outside their own country, and yet they seemed more accepting than any other group of kids I’d ever met. They didn’t know enough to judge me, and their ignorance provided me with a road map to individuality; I could take any direction I wished. I was grateful to retire from my school-fighting career.

A classmate once asked me what part of South America I came from. “You don’t look Mexican,” she noted, studying my face with interest. We sat a desk apart, waiting for our Shakespeare teacher, Mrs. Peacock, to make a uniformly late appearance. I was the only foreigner in the class and must’ve been completely mad for assuming I could handle Shakespeare. Nevertheless, I mulishly trudged through his works that semester just to prove to myself that I could. All the while, the students stayed at a respectful distance from me, guarded yet curious. But once we began to write our own plays and work together to direct and perform, it was clear that we had many things in common, like a knack for over-the-top Shakespearean parody. When Donna asked me that question, I found I wanted to give her a real answer. It came like a well-lathered ring off a swollen finger. I told her about my home, about the Romani who coiled their skirts onstage while I sat eating my dinner—kielbasa and cucumber sandwiches—behind the curtains. Exotic, she said. That’s what she called me. I had added that word to my list of favorites, and it had an entry of its own in my journal: exotic—strikingly, excitingly, or mysteriously unusual. Me.

* * *

Growing up, I had never felt striking, exciting, or mysterious—just weird.

In primary grades, before Nastya began to plot my annihilation, my classmates had nicknamed me “Rice,” a term used for Asians. It didn’t bother me. My own grandmother looked at me sideways, so how could I expect anything less from strangers?

Years passed and my growing resemblance to Grandma Ksenia finally put all paternity questions to rest. We had the same pronounced cheekbones, full lips, almond-shaped eyes. She accepted me into the fold, something Grandpa Andrei had done much earlier. Much later I found out that my father was one tenth Mongolian. It still did not make me exotic.

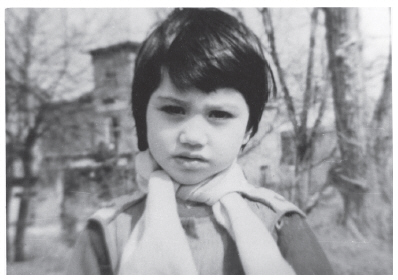

Back when I went by “Rice”

Dozens of nationalities lived in Russia, but unless you were actually from Russia, you were often treated like a lower life-form—a relic of an attitude we had inherited from that first generation of Soviets and the time when Lenin and his comrades lassoed fourteen countries to create a union governed by Russia. The USSR was like the modern European Union, only with one ruling nation, Russia. The new country prospered with thousands of jobs, new roads, and markets full of foods from every season, with schools for kids who’d never seen a book before. Not since the Roman Empire had the world witnessed such an undertaking. There remained two problems: (1) although the union comprised fifteen republics, fourteen were treated as slightly substandard; and (2) even as the most reluctant of Soviets had never had it better, there was the small matter of freedom. No republic had the choice to secede if things didn’t work out.

Even if you pretended to be Russian, once someone checked your ID the truth came out. Soviet IDs segregated people according to their nationality. A Chukchi remained a Chukchi, uneducated and dim-witted, even if they spoke flawless Russian. An Ossetian was just the man to hire if you wished to have someone rubbed out. A Ukrainian was never quite as pure-blooded as a Russian, and so on. Even if you lived in Russia all your life, your nationality shaped people’s perception of you.

No Romani in their right mind would put “Gypsy” in their documents, unless they particularly enjoyed the breeze from doors slamming in their faces. Like Romani, many Jews masqueraded as Russians, and if they could not be that, then Ukrainian, or at the very least Moldavian. We were all branded by our identities. Luckily for my family, our mix of nationalities made it easier to choose the most advantageous one. Grandma Ksenia and Dad were both Greek according to their IDs because Grandma Ksenia’s father was a full-blooded Greek. And being a Greek in Russia was better than being a Roma.

The union created an amazing blend of backgrounds and some of the most beautiful people in the world. I once met a gorgeous blond-haired, blue-eyed Mongolian, and yet an American horse breeder my father once drank a toast with was considered more exotic in my country than this girl.

Who knew that people in America would think so differently? I wondered for a long time. Wondered until something so simple yet powerful became clear to me. Since perceptions are ever changing, as was the case at hand, the only thing left to do was to trust your own opinions. If you think you are something, that’s what you become.