ENDINGS AND BEGINNINGS

Reprieve came from the most unexpected place. Grandpa Andrei died of kidney failure and my father became a beehive no one dared to disturb. He endured the loss in solitude, even his guitar mute. My own grief, two years after Ruslan’s murder, was like an old cut seeping blood again.

For days, Dad talked about the past. The time he drove his father nuts when he gambled away the old man’s gold cigarette case, and about having to steal it back or get kicked out of the band. Finally Olga put him on a plane to Moscow for the funeral. While he was gone, Olga and I didn’t fight, too worried over Dad’s state.

He came back with two waterfalls of silver down the outer edges of his beard: his own father’s trademark.

Several weeks later, and without telling Olga, Dad bought a plane ticket for Grandma Ksenia. With Grandpa gone, it was up to my father, as per Romani tradition, to take care of his mother. When Dad informed Olga of his mother’s arrival that very day, my stepmother hurled a nearby vase at his head (one of many airborne attacks to follow).

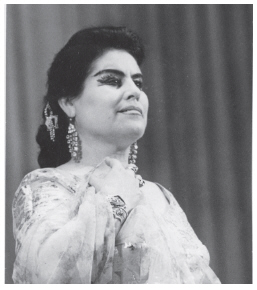

Grandpa Andrei, with Dad and Aunt Laura, 1953

Out of all my relatives, I would turn out most like Grandma Ksenia. Back in our days of rancor, of course, neither of us had expected such irony; although I was named after her, Oksana being a derivative of Ksenia, she’d been a stranger to me for all of our time in Russia, and I honestly didn’t know the proper way to act around her now that she was coming to America. My childhood memories are vibrant with the faces of my grandfather, my parents, and the many band members. Grandma Ksenia is the only shadow, perhaps because we often seemed to clash—not only over my questionable lineage but also over silly things like the whereabouts of Grandma’s favorite Pavlovoposadsky shawl or how her cold cream ended up smeared all over our cat’s face. I admit there were times I was Dennis the Menace to her Mr. Wilson, but we did have our moments of truce.

I loved visiting her at Easter. Dad’s family, like most Romani, was very religious. Even Baba Varya attended church services. Romani don’t have a common religion, often adopting that of their country. Their original beliefs were similar to those of many tribal people: the land is the mother and all depends on her mercy. But the people I grew up with were Russian Orthodox, especially Grandma Ksenia.

Every Easter our visit followed the same course: we’d walk up the steps where Grandma already waited, having phoned earlier to make certain we were coming. “Isus voskres (Jesus has risen),” she’d say, and kiss us one by one on each cheek. We took turns replying, “Vo istinnoh voskres (In truth, he has risen).”

Inside the house, the aroma of citrus and vanilla led me to the pantry. I cracked the door and found my prize under the pristine white cloth: paska, a traditional Easter bread as tall as a ten-gallon hat. From its flushed russet crust a fragrant cloud of steam escaped. I wanted to break off a piece and taste the sticky-sweet raisins waiting on the inside. Last time I did that, I was grounded for two weeks, but it was worth it. Grandma was a fine baker.

Now Grandma walked through the door with Dad at her back, and I hardly knew her. She held herself as if making a stage entrance, an action so instinctive that she hardly noticed it. Two years had passed since I last saw her. She had aged twenty. Her short hair lay sparse and coarse, with a generous band of silver at the roots. Time had creased her face, rubbed the pride from her now sunken eyes, pinched once perfectly contoured cheekbones. The only sign of the well-known songstress was the crimson-red lipstick. When I was little, I thought she kissed pomegranates.

“My dear granddaughter,” she said, and spread her arms. All my qualms forgotten, I went to her.

Olga came clinking out to greet her, dressed up in her finest. She must’ve worn all of her jewelry at once.

“Welcome to my home, Ksenia Fyodorovna.”

She led Grandma away, as if showing the house and the furniture couldn’t have waited for later. But Dad’s shoulders visibly relaxed.

Several weeks went by in startling peace. It became a habit for my grandmother and me to listen to the morning radio program in Russian. The first part was a thirty-minute exercise routine accompanied by a crisp piano. It had been created especially for seniors, but I didn’t mind that, so surprised was I at the old woman’s determination to finish each day’s routine. We’d follow the instructor’s voice. “Turn at the waist from side to side! Now stride in place! Get those knees higher! One, two, three, four! Don’t forget to breathe! Chest open! Chin lifted!” We also started taking the bus to the beach every time Dad and Olga forgot their truce and turned up the volume. “Adults have no time for the children or the old,” Grandma would say on our way out the door. Santa Monica was her favorite beach, though she swore her preference had nothing to do with the sweaty guys playing volleyball in their Speedos. We’d sit on a bench and I’d tease her about it. “Grandma, I never knew you liked sports so much.”

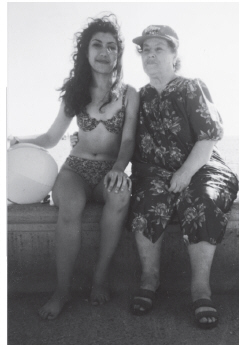

Grandma Ksenia could bring an entire theater to tears

“Child, if I were twenty years younger I’d be out chasing that ball.”

“With all those hairy guys?”

“What other kinds are there?” She chuckled at the shock on my face.

Later I found black-and-white pictures of my grandparents on the Black Sea coast where they vacationed every year. Grandma’s legs are ballerina-slender and Grandpa’s legs are not bad, either, quads and calves like rocks beneath a flowing river. She’s propped up on a huge boulder near the water, holding one of those Chinese paper umbrellas with peacocks painted on it, looking like a wartime pinup girl. Next time we went to Santa Monica, I brought a camera. The only picture of us together was taken there, by a man who claimed to have once dated Marilyn Monroe.

On Santa Monica beach

Grandma Ksenia had spent years wading through the gossip and scandal of stage life, and she was an early riser. Both turned out to be bad news for Olga, whose pawnshop trips and disappearances were becoming habitual. When Grandma told Dad that she suspected something shady, an affair perhaps, he confronted his wife.

“Why doesn’t your mother keep quiet and enjoy our hospitality?” she said.

I had just come from school. Grandma Ksenia stood in the living room between Dad and Olga.

“Is it true, Olga?” Dad demanded. “Are you sleeping with another man?”

Grandma implored him to sit. “Calm down.”

Olga’s face, her bulging eyes, spit hatred at the older woman. She stood in the kitchen doorway, her normally braided hair a thick black foam of curls down her back. She jabbed a finger at Grandma Ksenia.

“Buy her a ticket back to Moscow.”

Over Grandma’s shushing, the argument inflated until Olga stormed into the kitchen. I’d thought she went in search of her keys to get away, but she ran back with a ten-pound sack of oranges, which she heaved over her head and flung at the old woman. The sack sailed across the living room. I scrabbled to intercept it, and Dad shoved Grandma aside as it crashed into her shoulder.

“Nou suchara, podozhdi! Ia seychas boshkou tebe otorvliu! (Just wait, you bitch! I’ll rip your head off!)” Dad lunged at Olga, with me and Grandma dragging him back.

“If she’s not gone in a week, I swear, Valerio, I’ll destroy all of you,” Olga shouted.

She was gone for four days. My father found a home on the other side of town, owned by a bedridden Russian immigrant, where Grandma Ksenia was to live from now on. I couldn’t understand why he hadn’t stood up to Olga, and I am not sure I do now.

As soon as Mom had a couple days off from her nonstop overtime shifts, she and Roxy drove down to see Grandma Ksenia—the woman who’d hated her, who’d cut off all contact after the divorce.

While she and Mom talked in soft tones so as not to wake Grandma’s landlord from his nap, I studied the grout between the tiles and the dull green curtains, the kind you’d see in motel rooms. The clinical-looking tile floors throughout and the smell of a dying man in the next room made my skin break out into goose bumps. I listened to the metallic moans ensuing from Grandma’s bed every time she moved, and picked my nails with topmost dedication; anything to spare me the bedraggled sight of my once elegant grandmother.

My sister was saying things I tried to follow but failed.

“Oksana. Oksana. Oksaana!”

“What?” I turned to Roxy, oddly grateful.

“I was saying that my school looks like a flying saucer and the playground gets so hot that it burns the soles off my shoes. I hate it there.”

“Nora. Dochenka,” Grandma was saying. “Never in my life would I have imagined this. But perhaps it’s my punishment for being so cruel to you. I regret every one of those days.”

“Don’t think about the past, Mother.” Mom was leaning close, holding the old woman’s hand. “This home looks lovely. Very quiet neighborhood.”

“It is. It is.” But giant tears spilled from her eyes.

“Mother. What is wrong?”

“I don’t think I can do this.”

“Do what?”

“Oy, dochenka. He’s so heavy. It takes me an hour to get him out of the bed and to the toilet. Most of the time he doesn’t even make it that long and soils himself right there in the hallway. Good thing it’s all tile.”

A cold weight was lodged inside my throat, and I looked at Roxy, who thankfully wasn’t paying much attention, picking out an outfit for her Barbie instead.

Neither Mom nor I had known that Grandma Ksenia was the old man’s live-in caretaker, that she woke up nearly every night to clean the excrement from his behind and change his filthy bedsheets.

Mom did ask Grandma if she wanted to move in with her, but she said, “My place is here with my son.” But soon after our visit, per Olga’s demands, Grandma Ksenia went back to Russia. She would die there a few months later.

* * *

Olga had calmed down for a while. Did she feel guilty for sending the old woman away to a lousy end? I hoped so. I did, though there was nothing I could’ve done to improve the situation. The way you knew Olga’s conscience was stirring was when she spent more time doing the dishes, a task she executed rather poorly. This meant that my father was also in the kitchen constantly rewashing them. He had more time on his hands now, since he barely saw his clients and had canceled most of his gigs. “The fibers in the rope of our family,” he said once, “are splitting one by one.”

During this time a man came to see my father, walking with shoulders hunched as if preparing for an air raid. Bob’s newborn daughter was dying and he begged my father for help. He had heard about Dad from a friend who avoided knee surgery after a regimen Dad prescribed, involving a compress of dried horse sorrel and garlic. That same day the three of us, me as a translator, drove down to Huntington Hospital in Pasadena.

His wife, Kim, was crying when we came in. She clumsily wiped the wetness away with the edge of the sheet and smiled at us.

“I don’t know if I can help,” my father said, and I translated. “Something like this is in God’s hands.”

Kim sat up straighter and Bob immediately added another pillow at her back. He remained at her side, biting the nail of his index finger.

“The doctor wants me to just give up,” Kim said. “If you were me, would you give up?”

As I repeated the words in Russian, Dad considered the couple with respect.

“We’ll pay whatever you ask,” Bob pleaded.

“I do what I can do,” Dad said in English. “But I no take money.”

Did I notice how quickly and earnestly my father was willing to help these strangers? Yes. Even if I was ashamed for the misplaced envy, I let it creep into my mind anyway. This was the first time I’d seen Dad interact with a client, and his kindness seemed limitless. He was a Zen master, breathing hope and tranquillity into the lungs of the lost. I envied that little girl whose life was slipping away, begrudged her my father’s Zen. What was wrong with me? Was I really that desperate?

The doctor came in and did a double take. I would’ve laughed if the situation hadn’t been so dire. Dad had on one of his black fedoras and a long leather trench coat beneath which he wore a black dress shirt, black leather pants, and steel-toed cowboy boots. His long hair trailed down his back. The doc eyed it before seeming to remember why he’d come in.

“Any change?” Kim’s fingers twisted the sheet over her belly.

The doctor shook his head.

Dad asked the couple if he could talk to the doctor in private, and when they consented we stepped out into the hallway. Dad asked several questions about the baby.

“She has a metabolic disorder,” the doctor said.

Perplexed, I admitted that I didn’t know what that meant, but Dad wasn’t discouraged.

“You tell me not like doctor but like patient,” he suggested to the man, who clearly wasn’t used to being questioned.

“If you wish, although I don’t see the difference.”

“Please.”

“She’s like a car that’s running out of gas. Once it’s gone, she’ll stop working.”

Back in the room Dad rubbed his hands together. “I no promise anything, but will pray. You must hold baby, never let her down, and feed her more. Take turn but keep her close to your body all time. She not make life energy, so you give her yours, keep her safe with yours.”

The couple looked incredulous. I was doubtful myself, but I could tell that hope was the only thing left to them, and then I remembered Paywand and her theories on magic being all-encompassing and attainable by everyone. My father always tried to explain to his clients the logic behind every séance or healing process: All matter is energy. We are energy. God is energy. Devil is energy. It has neither form nor boundaries. It is what we make of it.

The couple followed my father’s instructions, and though the staff objected at first, eventually they let the parents be. On the tenth day the doctors announced that although the metabolic problem had inexplicably disappeared, the little girl’s kidneys were now failing. Three weeks later it was her heart. But the parents kept holding her.

Six years later Kim wrote an article about her daughter’s miraculous recovery, which was published in a Russian magazine called Panorama. She spoke of the Gypsy man who spent days and nights at her daughter’s side.

The funny thing is that my father’s own mending took place during his visits to the hospital, on his vigils, while he prayed over the sleeping baby. Without her, who knows if he’d ever have snapped out of his grief.

Life has a funny way of sweeping you back into its current.