WHERE I FINALLY SAY IT

Pavel returned at last to Ukraine, and to my astonishment Dad was contemplating the man’s advice. He finally admitted that he might’ve gotten himself involved in things better left alone.

It was 1993, my senior year. Finals hovered. My father’s question nagged at me. It was one thing to rebel against my family’s ideals, but when it came down to it, what exactly did I plan on doing instead?

Strangely enough, it was Brandon who helped me answer that question.

Annie, Cruz, Alison, and I were shooting pool one evening on the back patio of Annie’s house.

Brandon showed up wearing a long black dress with lacy trim at the sleeves and the hem. He carried a thick packet under one arm. “So, I’ve decided,” he said, flopping noisily into a lawn chair, then sat up and patted its neighbor, waiting for me to sit next to him.

“To join a convent?” Annie said.

“Bitch.” Brandon blew her a kiss and turned back to me. “You, missy, are going to college.” He handed me the packet as I sat down.

Dad once told me that when he tried to get into some big-name Moscow university, an admissions counselor told him that Gypsies were better off sticking to what they did best: making the music that Soviets loved so much. Although the man didn’t mean to be insulting, my father never forgot it.

“I don’t know,” I said. “Don’t you have to pay like a gazillion dollars for college?”

“Not if you qualify for a Pell Grant,” Brandon singsonged.

Alison huffed. “Nice. The foreigners get free school. I was born here and I had to write a fucking essay to get a fucking scholarship.” She’d been sitting on the edge of the pool table, uncrossing her legs every time Cruz walked by.

Annie took a shot at a green ball, then straightened. “Don’t listen to her. She’s bitter because her parents are sending her to Oklahoma State instead of to her grandmother’s in France.” The ball bounced off one side and came to a stop inches in front of the intended pocket. She stuck out her tongue at Cruz after he nudged the ball in.

“Do you have a major in mind?” Annie asked me.

“You.” Brandon snapped his fingers at Annie, shifting his legs under a sea of lacy hem. “Don’t pressure her. We still have time.”

“Did you guys take that career assessment yet? I got arts,” Annie said.

“Me, too,” Brandon said. “Way to go, girl. I see a Vegas burlesque in our future.”

Alison began preening as Cruz came around the table corner to take another shot. “I got modeling,” she said.

“You liar. There’s no modeling category in those tests.”

“Yes, there is, Brandon. I’ll show it to you.”

“What about you, Cruz?” I asked.

“Oh, no. You guys leave me out of this.”

Once he said that, everyone wanted to know.

“Fine, but don’t laugh. Biotechnology.”

Brandon pealed with laughter until his eyeliner ran and he started coughing. “Sorry, I’m sorry,” he said when Cruz gave him the finger. “It’s just … I can’t even pronounce that … without imagining you in one of those cute lab coats and goggles. Okay, okay, I’m stopping.” He cleared his throat and took a long drag from the joint Annie passed him. Exhaling slowly, he said, “Right now,” and then giggled again.

“Guys, I remembered something funny.” Alison jumped down from the table. “When I lived at Grandma’s in Paris, we’d go to the local café in the mornings, and every time, a gang of street Gypsies would start begging us for money. Mostly kids. And they’d grope me with their grimy fingers. I’d wonder why their parents didn’t make them bathe. But then Grandma told me they stayed dirty on purpose; that way an outsider couldn’t identify them if they stole something.”

“Alison,” Cruz barked. He’d stopped playing, and his cheeks had splotches of red. Something akin to that, red and angry, was spreading inside of me, too.

She continued. “Grandma told me the Gypsies would put a curse on us if we didn’t give them something. She also taught me a trick to ward off their curses.”

The roof of my mouth grew as ashy as a chimney.

“Every time you walk by a Gyp, you take two fingers and place them here.” She started to rub her fingers inside her inner thigh. “Like this.”

I jumped her, my breath snagging on flames. My fingers ripped at her silky hair, and when I wrapped my legs around her middle, we toppled over. Everything around me blurred. Only her face remained in focus, like a clear bright chip inside a kaleidoscope. I slapped at her, clumps of her hair tangling in my sweaty hands. I was screaming things in Russian, oblivious to everything else. Alison punched me in the mouth. Pain pricked against my skin. The others were shouting for us to stop. But the loudest noise was my own heartbeat, my own blood.

When Cruz tore me away from Alison, it was only a few moments into the fight, but I felt like we’d been at it for hours. His arms steadied me and my rage retreated.

Alison sobbed on the floor, her face angry pink and bloody where my nails scored tracks. “Get that fucking bitch away from me,” she screamed.

Cruz dragged me toward the front door, but all I wanted to do was rip out Alison’s tongue by its root. I hoped she knew now that she’d been taunting the wrong Gypsy.

Once on the sidewalk, Cruz firmly led me away from Annie’s house.

“My backpack,” I said, wiping my eyes with my shirtsleeves.

“I’ll bring it by tomorrow. Come on, I’ll take you home.”

I shrugged away. “You’re always taking me home. Is that your answer to everything? In case you haven’t noticed, I’ve been known to find my own way. Isn’t that amazing, someone so primitive with the ability to follow a sidewalk?”

“Your lip is bleeding.”

“I’m gonna go now.” I started down the street. The energy that had propelled my fury earlier had drained. My legs turned cottony. The left side of my face began to throb and I tasted blood.

“You want to talk?” He was following a few feet behind.

“Can’t you leave me alone?”

“That’s the question of the day, isn’t it?”

When we got to my house, lights behind the curtains suggested that people were up. I felt like shit and probably looked worse; no way was I going through the front door.

“My window should be open,” I said.

The screen came off easily, and I slipped inside. I turned on the closet light, which glowed softly but wasn’t bright enough to be seen from under the door. “Come on,” I mouthed, and motioned for Cruz to follow me.

He stood just outside, hands in the back pockets of his jeans. “I should go.”

I stuck my head out, elbows on the windowsill. If my father heard voices outside my bedroom he’d definitely investigate, so I whispered, “I didn’t mean to go off on you like that.”

“Don’t worry about it.” He crossed his arms. It was the first indication that I might’ve truly hurt his feelings this time. When I said those petty things I hadn’t given a thought to how callous they must’ve sounded, that here was a guy who’d been listening to my bullshit for three years now and yet was still standing outside my window.

I reached out and wrapped a hand around his forearm. “Please stay.”

He didn’t say anything, but climbed in. The sill was higher on the inside than it looked and he tumbled to the floor. I grabbed him and we both went down, me shushing, him laughing.

A few minutes later we were sitting on the floor face-to-face while Cruz cleaned the blood off my lip. The closet light drew shadows around us. My face throbbed even more than before, and I winced every time he touched it.

“Hold still. Here’s something to distract you.”

I felt him press a piece of paper into my hand. “What is it?”

“A surprise,” he said.

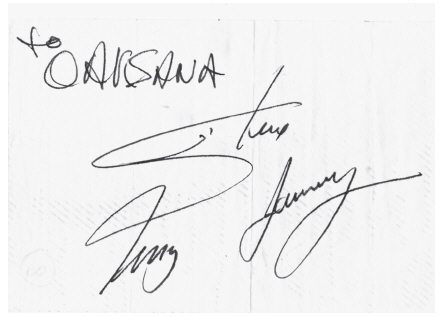

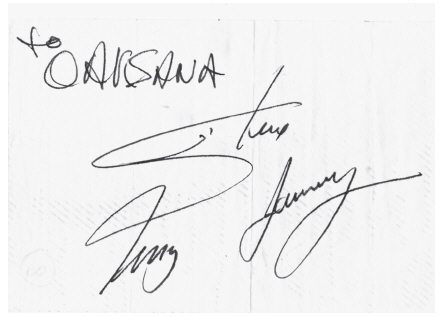

I scanned the contents of the wallet-size note, barely making out the scribbles. It read:

To Oaksana

Steve Perry

Journey

“I can’t make out the name.”

“It’s from Steve Perry. You know, the singer for Journey.”

“Oh my God. How did you get it?”

“Believe it or not, we were having lunch at the same restaurant, and I harassed him until he gave in. But he did misspell your name. Sorry about that. I was going to ask him to rewrite it, but he threatened to call security.”

“Wow, I have Steve Perry’s autograph. Did you touch him? Kidding. This is amazing.”

Very gently he felt the puffiness around my lower lip. “I can’t believe you jumped Alison like that—not that she didn’t deserve it. You’re a fierce Gypsy warrior woman.”

He dipped a clean tissue in the glass of water sitting on the floor by the bed.

I followed the motion of his hand. It kept me distracted from the way he sucked in his cheeks in concentration. Our knees touched. It felt like I was being pulled to him by a rubber band stretched tight around us. Did he feel it, too? His fingertips brushed my face as he continued his ministrations, leaving strokes of tingle on my skin.

“Sometimes I wonder why you’re still here,” I said.

“You know why.”

“I haven’t told my father about us.” I had thought earlier that I had the strength, but then the right time never appeared.

Cruz let his hands fall. “There’s nothing to tell, is there?”

If I could’ve come up with a perfect excuse for my silence, I would have. Anything to erase the hurt from his face. But I didn’t think that would be fair. “Before, you asked me to be honest,” I said. “That’s what I’m trying to do here.”

“Yeah, I just didn’t expect you to be this honest. I thought you’d eventually fall for my animal magnetism.” He grinned for a second, then went back to cleaning. “So what now?”

“I don’t know. The logical thing would be to stop seeing each other.”

“Why?” When I shook my head, he took my face in his hands. “What was the first thing you thought when I asked you that? Don’t think about it. Just say it.”

“My mother ran away with my father,” I blurted out without thinking at all. It came as naturally as if the words had always hovered above my head, waiting to be acknowledged. “She claims it ruined her life. By listening to her impulses, she left herself behind.”

Cruz let go. The look on his face startled me, as if I were a fortune-teller who’d revealed a secret of his that no one could’ve possibly known. It compelled me to load the silence with chatter.

“I’ve been thinking of moving to Vegas after graduation. Maybe take Brandon’s advice. College sounds like something I could do.” I didn’t tell him that most likely I’d have no choice. My mother would never let me forget our agreement, and besides, someone needed to be there to intercept the liquor bottles.

“Isn’t that kind of like running away?” he said, tossing the crumpled, bloody tissue on the floor.

“Don’t say that—”

“Come on. Stay here.”

“And do what?”

His shoulders tightened and he pulled away from me as if I’d slapped him. “You can be so fucking cold sometimes.” Rising from the floor, he pulled the window curtain aside. “I’ll see you later.”

As always, I’d managed to make a mess of things.

I grabbed him by his shirt. “No, I’m sorry. I didn’t mean it that way.”

But he wasn’t listening, already halfway out.

“Wait. I love you,” I blurted out so fast that even I wasn’t sure how it happened.

“Say that again.”

After climbing back in, he leaned on the windowsill and in a somber tone said, “One more time. I don’t think I heard that right.”

And so I stopped searching for fault lines in Cruz’s belief in our future together. If nothing else, I thought, I could learn a thing or two from him about trust. And when I said, “I love you,” I meant it. I loved him the way we do before we learn to classify emotions according to our expectations.

One evening while taking a walk down Hollywood Boulevard, we came across a homeless man propped up against the wall of some posh restaurant. He was missing one sneaker, but his clothes, a denim shirt and jeans, were surprisingly clean of the encrusted grime you’d expect on someone roaming the streets. He peered sightlessly into the distance. People passed, some dropping coins on the sidewalk beside him, but Cruz slowed down and then crouched in front of him.

“Hey. You okay, man?” Cruz touched the man’s shoulder. “You need help? Some food?”

The stranger’s eyes focused and he sat up slightly. “I’m … What day is it?”

Out of the blue, he began to sob, the smell of liquor on his breath like a blow from a shovel. Cruz took him by the elbow and helped him up.

“Come on. It’s way too cold out here. My house is just around the corner.”

“Are you sure?” I whispered after Cruz had left the man in his kitchen to grab a towel from the linen closet. “What if he’s a serial killer or something?”

“Did you see the ring on his finger?” he said. “He’s not homeless.”

Cruz sat across the table from the man, I leaned on the kitchen counter, hands gripping it at my back, and we listened to the man’s story, because there wasn’t much we could say to make anything better. He’d been drunk for days over the loss of his wife, murdered a year before.

“I don’t know what to do next.” Ted rubbed his eyes with the heels of his hands.

“When I was eight,” Cruz said, and cleared his throat, “my mom one day left for her sister’s house and … she was gone.”

Tears bloomed in my eyes. Cruz’s gaze was fixed on the table’s smooth surface. “She didn’t just leave. The Manaus police aren’t interested in what I think.”

I imagined Cruz as a kid, thinking he’d been abandoned until he was told a truth even more terrible.

“I stopped going to school, so Papai sent me here. Before I left, he said, ‘Nothing in this life remains unchanged, o meu menino. Not even mountains.’”

We didn’t see Ted after that night.

But after the revelation of Cruz’s secret—his missing mother—many things about him made sense. The snapshot pinned to his bedroom wall was more proof of his state of mind than anything he could’ve said. I’d never imagined that his sympathetic nature was born out of something more than a carefree upbringing. Instead, it concealed heartbreak. I called Zhanna that very night.

“How do you always manage to fall for these unfinished boys?” she’d said. “Ruslan and now this … this Brazilets.”

“They’re not unfinished. What does that mean, anyway?”

“Men without mothers. Their souls are split, unlucky. That’s why Ruslan is haunting you still. You’re the only woman who loved him.”

I rolled my eyes at the phone. “Come on.”

“Bez materinskoy lubvy malchiki stanovyatsa slomannimi muzhchinami (Without a mother’s love, boys grow into broken men).”

“We’re in control of our reality no matter what our families are like, and Ruslan is in Russia, all the way across the ocean.”

“I told you to get that scarf back,” she said.

The conversation was taking a familiar turn, but this time I didn’t try to change the subject or make jokes the way I had done in the past.

“I want you to do something for me,” I said.

“I’m not digging up graves.”

“Can you burn my journal?”

There was a pause, and I waited for her to start cursing in Rromanes the way she did when particularly annoyed.

“Forget the scarf. Burn the book, okay?”

I love my cousin for not seeking an explanation, for not gloating because her crazy ideas might’ve gotten to me. The burning held meaning in ceremony alone. There was no magic attached to it, but when she called me back some days later to tell me it was done, my room seemed brighter and the colors more solid. My own reflection in the dresser mirror was that of a young woman with fewer shadows in her heart.

* * *

With Cruz, for the first time I felt free to remember that trust was as necessary as air. It’d do me good, I finally decided, to try on a bit of happiness. Maybe I was stitching up the tear in my coat, and who knew, maybe I could help Cruz heal, too.

We spent most of the rest of the school year together.

I began to sneak him into my room while my family slept. We broke rules. We were reckless. Cruz brought tapes and books, and bottles of the Yoo-hoo I loved. And I called him a dork for it. We lay on the floor, chilly-hot where our bodies touched. We shared headphones, listened to music, and got drunk on kisses and chocolate.

Cruz kept trying to convince me to tell my family, chastising me for losing my courage.

Turned out I didn’t have to, because my father found out for himself.

One February afternoon he woke up early, around five, and walked in on Cruz and me smooching on my bed. He swung the bedroom door against the wall so hard it nearly came off its hinges. Olga peered from around his shoulder, and at the sight of another man’s naked chest cried out, “Nu ty dayosh’ (Well, how about that)!” Cruz had little time to collect himself before my father had him by his hair and me by mine. Olga forcefully nudged him away from us, but nothing could get through to him now.

Roxy, who’d come to visit for a week, ran into the room in the princess pajamas she had on all day, her ponytail skewed to one side.

“Stop, Papa. Stop!” She pulled on Dad’s pants, but he didn’t even acknowledge her presence.

“Nu pezdets tebe ublyudok ti yobanniy (You’re fucked, you fucking mongrel)!” He hurled Cruz into the hallway. Before I could run out, he pushed me back into the bedroom and slammed the door in my face.

I scrambled for the window, but before I could climb out, Olga pulled me inside by my hair.

“Let go, Olga.”

Roxy, who was still in the room, forgotten by all, squeezed in between us and yelled, “Leave her alone!”

Like Dad, Olga ignored my little sister, yanking at my hair once again. “What do you think you’re doing?”

I twisted around, gripping her hands with mine, but no matter how I pleaded with her, she wouldn’t get out of my way. When my eleven-year-old sister called our stepmother a bitch, Olga finally threw her out of the room.

Eventually the noise outside the door subsided. I crumpled up on the bed. After a while I stopped wiping away the tears and let them soak into my pillow.

When I woke up, the house was quiet. I was alone. Fear had settled inside my rib cage. Olga came in with a tray of food and set it on the desk.

“Where is he?” I asked.

She clucked her tongue with her hands on her hips. “Ay-ay-ay, Oksana.”

“What did he do to him?”

“Don’t even think about going out that window,” she said when I moved. “We know where he lives. Trust me. You don’t want your father anywhere near that boy right now. His mood is black enough for murder.” My father bellowed for her from the other end of the house. Olga answered and turned to leave. “It’s obvious you’re ready to marry. But now that you’ve lain with some gadjo, who hasn’t as much as a decent family to his name, who’ll have you?”

I smashed the tray against the door as she closed it.

For two days I was a prisoner. Dad refused to talk, wouldn’t look at me. I was forbidden to go out, even to school—especially not to school. Olga created a long list of chores for me to do as punishment, and that kept me busy: scrub the floors, wash the windows, and serve as much tea as was required. On several occasions I started to explain to them that Cruz and I weren’t doing anything wrong.

My only companion was Roxy. We weren’t supposed to be talking, so she sneaked into my room when everyone else slept. My little sister did her best to cheer me up with stories of Vegas and her many friends. She told me about our mother building a cardboard prototype of an automated slot machine she called a “talking slut.” (I’d tried to correct her pronunciation, but I eventually gave up.) I found the idea brilliant: a customer could play with it as if it were a living person. Quite sure her invention would change Vegas forever, Mom took the talking slut to a casino manager. “He laughed at her,” Roxy whispered to me. “Told her that people don’t come to Las Vegas to hear machines talk.” Several years later talking sluts popped up all over the valley, and Mom was furious enough to boycott casinos for a whole month.

“Let’s play video charades,” Roxy said.

It was a game we’d made up years ago in Moscow when one of Dad’s friends brought a pirated VHS tape with six hours of music videos. They’d been recorded straight from MTV, commercials and all. Roxy and I wore that tape out until we could act out every video. She loved to sit on the floor and guess which singer or group I was. I’d bound up and down as if on coiled springs and shake my imaginary skirt, singing, “Girlz jus vanna hav fu-un.” Roxy’d jab a finger at me. “Crazy lady with a partially shaved head!” Or I’d spin around with “Youspinmerountrount bround round round—” “Girlyguy!” she’d scream. “I knew that one right away!”

Our all-time favorite, now that I think back, was my rendition of Def Leppard’s “Pour Some Sugar on Me.” Wearing a mop head for metal hair and one of Dad’s leather vests, I’d squeeze my fists in front of my face and shout, “Put that shuba on me.” Which literally translated into “Put that fur coat on me.”

I wished I could seize those carefree moments and play with Roxy like I used to, but I couldn’t get the image of my father beating Cruz out of my mind.

“I don’t even remember how to play it anymore,” I said.

Roxy frowned and then jumped off the bed to strike a pose that I immediately recognized as a move from Michael Jackson’s “Thriller.”

“Chamon,” she said. “I’ll go first.”

* * *

Three days later my sister went back to Vegas and Dad spoke his first words to me. “You’ve shamed this family.”

I was cutting onions for beef stew on top of the wooden counter extension. The onions intended to squeeze every last tear from my eyes, and a flood of emotion pushed dangerously against the back of my throat. “What family?” I blurted out.

His chair creaked as he leaned back. “What does that mean?”

“The family you walked out on, or the one you and Olga are doing such a great job destroying?”

“Our affairs don’t concern you.”

“But they do.” I left the knife on the board and turned around to face him. “You think because we’re kids, we don’t understand things. We watch you people rip everything apart without a thought for what it does to us, and we can’t do anything about it.”

A shadow of sadness flitted across my father’s face before it hardened. “Don’t try to manipulate this conversation. It won’t work. I’m an adult and I know more about such things. Young guys like that have only one thing on their minds.”

The floodgate inside of me had been opened and I couldn’t contain the stuff spilling out. “All this time you’re too busy to talk about anything. You let Olga plan out my life, and now suddenly you have wisdom to share?” I couldn’t believe I was talking like this to my own father. He looked as surprised. “I didn’t do anything wrong,” I said.

“If you think sleeping with some nameless gadjo is right, then I should’ve listened to Olga a long time ago and married you off.”

“He’s not nameless,” I said. My ears burned with humiliation. “You taught him, remember? You, who never let me touch that guitar unless I’m polishing it! I didn’t sleep with him. And he’s not a gadjo, he’s Brazilian, and I love him!”

“He’s a bastard asshole motherfucker. If I see him again I’ll snap his neck like a pretzel.”

“Why, Dad?” I sat down across from him. “Why can’t you see all the good things I’ve done? Why is it so hard for you to trust me, to believe I’m smart enough to make the right choices?”

“You’re a girl.”

“I’m your daughter.”

“And your mother’s daughter.”

“And your daughter,” I repeated.

“A daughter who disobeys at every turn.” He sighed. “Would it be asking too much to have had just one boy?”

“I can do as well as any boy. Look. I found a job, on my own—”

“A job I forbade you to keep.”

“—and I got into magnet school without any help—”

“Yet another thing you did behind my back.”

“—only because I wanted you to be proud of me,” I said.

“Where does the lying end, Oksana? You ask me to trust you. How can I trust a child who cares nothing for my opinion? What else don’t I know?”

“You don’t know how much it hurt when you didn’t come to last year’s talent show. I got a personal note from the principal herself, you know. You were supposed to be there.”

“Is this what it’s all about?” He slapped his knee. “A high-school talent show? That was months ago. What’s the use bringing it up now?”

I reached out and covered his hand with mine. His skin was rough, sprinkled with coarse hairs, his fingers square-ended. A tattoo of a lute, hand-poked many years ago, had faded into gray.

“Trust me, Dad. I’ve got a good head on my shoulders. Even when I argue with you, I still understand that you want the best for me. Everything you say counts. But I’m not going to live your life, or Mom’s life. You guys had your chance.”

“But you must accept our guidance. You’re a girl, and there’s an army of assholes out there.”

“I will make mistakes. Please, let me. I do love Cruz but I won’t act stupid just because of it. And I’m playing this year’s show, and I want you to know that if you don’t come it’s okay. I might even end up working at some Vegas casino for the rest of my life. But that would be my choice. Isn’t that what you always wanted from Grandpa?”

With an overcast face, my father stood up and walked away.

Cruz kept calling, but I could never get to the phone before Olga snatched at it. When Annie called I was allowed a five-minute supervised exchange.

“Are you all right?” she said.

“Fine. You guys?”

“Cruz is going fucking berserk here. I haven’t heard so much dirty Portuguese since Cousin Roberto’s jail stint two years ago.”

The phone clicked and bumped.

“Do you want me to come get you?” Cruz’s voice. “It’s my fault. So fucking stupid.”

But I knew if fault were a name tag, it belonged on my chest. No amount of running could separate me from having kept a secret I knew would crush my father.

Dad and I didn’t speak to each other for days, and I didn’t dare see Cruz. But then one evening Dad called me into his studio. The sun crested the horizon, and the gold-threaded curtains sparkled in its rays. Dad sat at his desk, flyers spread over its surface like a lettered tablecloth.

“I’ve decided to stop the exorcisms,” he said. “You think I should call the newspapers first and change the ad, or reprint the flyers?”

“There’s a copier I can use at school on lunch breaks,” I said cautiously, and he handed me the master file.