7

Pull for the Shore, Sailor

The castaways shivered in the blackness of the thankfully calm Atlantic, waiting for . . . well, they hoped they were waiting for rescue. The Titanic had gone down at 2:20 A.M., and there were the unforgettable screams, and finally the quiet and hideous contemplation of what had just happened—and what might happen to them.

Conditions were not good, given the lack of light, food, water, rescue. The one thing they had in their favor was a calm sea. The Atlantic, Albert noted, was always rough, but not this one night. It was calmer than a lake. Young Ruth Becker thought it was like taking a boat ride on a mill pond.

Several of the refugees in Lifeboat 13 tried to prop up sagging spirits by assuring everyone that they had been told four or five steamers had been summoned and were on the way. Beesley recalled that people put great hope on the thought that the Olympic would be there by 2 P.M., based on crewmen’s calculations. As Beesley saw it, everyone was confident they would be rescued. One of the stokers predicted, “The sea will be covered with ships tomorrow afternoon: they will race up from all over the sea to find us.”

And yet there was that disheartening memory of the ship whose lights they could all see from the Titanic while she still floated, and it never came. There was also the light they had tried to row to, but it had disappeared. Nothing could really be sure, and this nagging doubt loomed behind any optimism about rescue. As Dodge noted, “Every pair of eyes were strained to the utmost, to discover the first sign of approaching help.” Mary Hewlett fished out letters to her daughters from her handbag, and someone set them afire one by one to provide a light. A few of the lifeboats had lanterns, and others burned paper, too, and “these facts led several in our boat to assert many times, that they saw a new light, which certainly must be a steamer’s light,” Dodge said. So many times their hopes were swallowed as cruelly as the Titanic had been. “With each disappointment, added gloom seemed to settle upon our little company, as they began to realize the seriousness of our situation,” Dodge recalled. Percy Thomas Oxenham reckoned that the five and a half hours adrift in doubt and darkness “were the most awful [hours] I ever put in.”

Around an hour after the Titanic had disappeared, someone on 13 said he could see a light glowing up from the horizon—it seemed low and man-made. The other survivors did not dare believe it at first. “No one . . . placed any credence in his statement,” Dodge noted; the glow looked at that moment like some of the other discouraging lights they had chased already. At first Albert thought it was an optical illusion, or he was afraid it would be, anyway, and he strained to see it again. However, shortly the sharp-eyed passenger could see two lights, and then even Dodge could discern one. Albert could tell it wasn’t a star or a planet, and it certainly wasn’t the dawn. Then suddenly he was sure: it was a light—a wavering light, a faint beam of hope! Everyone’s skepticism dwindled as the light grew brighter, until even the most pessimistic were rejoicing. Someone had known where they were! Someone was coming to their rescue! Suddenly there was something else to think about besides the cries of gruesome death they had just heard. There was sincere optimism that they might live through this terrible night. Their eyes fixed on the wavering beam. It got brighter and brighter, little by little, clearly coming toward them. After some time, as dawn approached, they could just make out the mast of a steamer. The refugees on 13 were thrilled but worried about being run down by their heroic rescuer. Their little boat was so dark. They managed to twist more letters into a torch and set fire to it, a stoker waving it aloft. “We were quite prepared to burn our coats if necessary,” Beesley said.

As the ship came into plain view, the men on 13 chorused into a ragged version of “Pull for the Shore, Sailor.” The words were well suited to their surging relief:

Light in the darkness, sailor, day is at hand! . . .

Drear was the voyage, sailor, now almost o’er,

Safe within the life boat, sailor, pull for the shore.

Pull for the shore, sailor, pull for the shore!

Heed not the rolling waves, but bend to the oar;

Safe in the life boat, sailor, cling to self no more!

Leave the poor old stranded wreck, and pull for the shore.

As Beesley noted, the quaveringly grateful singers on Lifeboat 13 were too overwhelmed to sing properly, so they tried a cheer, shouting out praise for Guglielmo Marconi for inventing the wireless, which had summoned their rescuer. No doubt the wobbly song and stronger cheer helped rouse them for the final difficult push, as the rescue ship had stopped some distance away. It was a tall order for the half-frozen men to row—they even had to row around a berg. Nor was the rowing easy; Oxenham, a strong stone cutter at age twenty-two, admitted, “When the Carpathia hove into sight nearly everyone in our boat was exhausted.”

But no one was focusing on the freezing weather or fatigue any longer. Men and women alike were crying “tears of joy mingled with tears of sorrow,” Sylvia reported. Dawn bloomed full and fresh into a rosy sky, revealing the rescue ship carefully stopped among the dreadful ice. “Never was dawn more welcome,” Sylvia said gratefully. Albert was startled to see all the ice around—and to see that it was beautiful. The ice was so harmless-looking. And the ice had in fact changed its cruel face to benevolence; after crushing the Titanic, the ice had surrounded the desperate flotilla of lifeboats and had protected them in the calm sea between bergs. Without that ironic protection, the nearly swamped lifeboats might have been overturned into the normally choppy Atlantic, which was actually colder than ice. In fact, that swath of ocean would have been frozen that night save for its salt content; its temperature was well below 32 degrees.

Lifeboat 13 was among the first to reach the rescue ship. As the light mustered itself into a true morning, Albert was startled to recognize the ship. It was the Carpathia, which they had spotted in Naples! She was on her return voyage to the Mediterranean, in fact. It was a remarkable turnaround in perspective—the Caldwells had flirted with the idea of taking the Carpathia in March, but had turned her down because she was a little ship. Now she looked so huge against the tiny lifeboat. The day Albert and Sylvia had looked at the Carpathia in Naples seemed long, long ago now, not just a few short weeks. Whole lifetimes had passed last night, after all.

Now, Sylvia and Albert, like everyone else, were deeply thankful to be unexpectedly added to the Carpathia’s passenger list. Her crew threw down a rope ladder, but things were getting tricky. As the sun came up, so did the wind, and the ocean was getting rough. “Our boat seemed longing to leave the side of the ship,” Sylvia noted. The danger, so close to safety, clutched everyone. Perhaps the motion was also enough to induce queasiness in Sylvia. She couldn’t climb the rope ladder due to the sheer cold, the rough seas, or her ongoing illness, so she sat on a rope swing and was pulled up. Some of the other women got the same treatment. The Carpathia’s crew lowered a sack for baby Alden, now in his daddy’s arms again. Albert stuffed Alden into the sack and watched his precious baby hoisted up the steep side of the Carpathia. The men, including Albert, scrambled up rope ladders.

Sylvia stumbled onto the Carpathia with her teeth chattering, numbed through. It was obvious that the crew had been up all night, waiting for them; the crew was nearing exhaustion. Sylvia tried to stammer out her appreciation to the Carpathia sailors who had pulled her up onto the ship. “Oh, thank you!” she managed.

“Don’t stop for that, we are only too happy to be here to do it,” one replied. Sylvia couldn’t walk—perhaps because her mysterious symptoms affected her feet or legs. Then again, maybe she was just too frozen. She had to be carried to the dining room, where she was given hot coffee and brandy, which was more a medication at that moment than a liquor. As the crewman placed her in a chair, Sylvia noted sadly the “sorry sight.” There were women all around the table, “wild eyed and haggard silently weeping.” Most were wearing nightgowns; they had not even managed to escape the Titanic with modest or warm clothing. Their hair was not put up as fashion demanded; it streamed down their backs. A foreign woman was calling out frantically for her baby. That was the only noise, other than sobbing, and Sylvia recognized the sobs as a release for so many of the women.

After warming up in the Carpathia’s dining room, the Caldwells moved to the deck to watch as the other lifeboats rowed toward the Carpathia. They sat together in stunned silence, a rare Titanic family. At first during the darkness they had thought that perhaps forty or fifty heroic crewmen who had remained aboard the sinking ship had been crying for help from the icy waters. Now they could see that they had grossly underestimated. The Caldwells didn’t know how many of their fellow passengers had been lost, but it quickly became obvious that they were one of the few families who had started out together on the Titanic’s short voyage and had completed it together. Counting parents traveling with children, couples traveling without children, and siblings traveling without parents, only one family in four who got onto the Titanic together got off together. More than seventy families vanished entirely.

The survival of all three of the Caldwells was their own miracle amidst so much heartbreaking tragedy, a miracle they could not celebrate except with subdued reverence. Sylvia told a reporter some time afterward, “As I look back over the perils of that fearful night, it seems miraculous that all three of us are yet together. The margin between life and death was so narrow.” So many people had lost a loved one or multiple loved ones. She noticed with dismay the scene repeated over and over among the Titanic’s surviving women: “A life boat would come up and the eager, half frozen wives and mothers stood and scanned the faces of those entering; another boat and those poor, wild eyes, never tireing, searched in vain.” Albert, too, was deeply saddened to watch the Titanic’s women who lined the rails of the Carpathia, scanning each incoming lifeboat “in the vain hope of seeing a husband, a father, a brother or perhaps a sweetheart who never came.” A rumor went around that some survivors had been picked up by another ship. Women who had yet to locate their husbands were on a roller coaster ride between utter despair and desperate hope.

And yet it always turned out to be hope toying with them in the most merciless way. One of the women searching in vain was the Caldwells’ Titanic dinner companion, Lottie Collyer. “We could only rush frantically from group to group, searching the haggard faces, crying out names, and endless questions,” Mrs. Collyer recalled later. “No survivor knows better than I the bitter cruelty of disappointment and despair. I had a husband to search for, a husband whom in the greatness of my faith, I had believed would be found in one of the boats. He was not there.”

Captain Arthur Henry Rostron of the Carpathia had his wireless radio operator contact all ships in the vicinity, but the gravely final word came back, “We have no survivors.” Someone on the Carpathia began the bleak task of counting the Titanic’s passengers on board. “We knew then, after being counted, that 1,500 had been lost,” Albert said. And yet here they were, the intact Caldwell family, a gift of God—and of their guardian angel, that persistent stoker who had insisted they get off the Titanic. Gratefully, Albert asked to see the crewmen who had manned 13. He thanked them, particularly the stoker who had told them the raw truth about the damage to the Titanic.

It looked to Albert as though the Carpathia was full up, and conditions were crowded. There was plenty of food, “although it was a task [for the Carpathia’s kitchen staff] to cook quickly for such a large number” Albert commented. The Carpathia had been heading back to the Mediterranean, but Captain Rostron canceled that schedule and return to New York. The rescue ship turned around mid-day, and Albert “looked back at the great ice field with the great icebergs glistening in the noon day sun. They looked so beautiful and harmless.” But he sighed. Looks were cruelly deceiving. The proud Titanic lay at the bottom of the ocean, having taken with her “millions of dollars worth of property and hundreds of precious lives, having been crushed by one of those harmless looking objects.”

After a few hours Sylvia was sitting to one side with Alden on her lap. One of the Titanic stewards came by. He picked up Alden and hugged him tightly, tears welling up in his eyes. He didn’t say a word at first. Then, as Sylvia told it, “He put my babe in his arms, sat down by my side and said, ‘I have a son at home, just the age of this little fellow and I never saw two babies more alike.’” Both babies were lucky to still have fathers.

Albert’s own good fortune was brutally clear: he watched the Carpathia’s crew bury some of the Titanic’s men at sea. They had managed to swim to a lifeboat, but the Carpathia was too late to keep the soaked men from freezing to death. He spoke with one survivor who had made it through after swimming.

As the Caldwells quickly realized, most of the new widows aboard were immigrating to America, having never been there before. Sylvia eavesdropped on their conversations as they talked at the dining room tables or in corners where they were huddled. She overheard one say, “I have nothing in the world and I have no place to go since my husband is lost. But I am not afraid. I have always heard that the Americans were the kindest people in the world.” Sylvia sat up a little straighter at the compliment to her country that she herself had been gone from for such a significant time in her life that it seemed like another world. When she was last a resident of America in 1909, she was the daughter of her parents, a Harbaugh. Now she was a married former missionary with a husband and a child, a Caldwell with a son of her own. Another woman turned to Sylvia and said, “Now I am not saying this because you are an American; but some how I feel as if I were going to friends. I have never been to America but I would rather it was America I was going to, in this condition than any other country in the world.” Another snatch of conversation Sylvia overheard featured a woman worrying what would become of her family. A friend tried to comfort her. “Never mind, I never saw an American who didn’t have a big heart,” her companion said. “I am sure they will take good care of us.” As Sylvia said, “I think I was never so proud that I was American as then.”

For their part, the people on the Carpathia were certainly good to the shocked and bereaved survivors. A lady tore up her flannel nightgown to make diapers for babies; no doubt Alden was the recipient of this desperately needed generosity. Fellow Titanic survivor Margaret “Molly” Brown, the well-known Denver millionaire, took charge of the women aboard the Carpathia, including the Titanic’s own women, and organized them into a team to replace the clothes of children who by now had soiled, spit up on, spilled on, or in other ways dirtied their clothing. Molly Brown and the ladies appropriated the Carpathia’s steamer rugs and made them into poncho-like dresses or coats for the little ones. Alden really needed a coat; some stranger had made a souvenir of at least one of the Titanic’s steamer rugs that he had been swaddled in when the Carpathia crew hoisted him from the lifeboat. Molly Brown brought a homemade coat to little Alden personally. Sylvia’s parents lived in Colorado, so perhaps Sylvia was bold enough to speak of home with Mrs. Brown.

Alden looked like an urchin in his strange garment, and technically, he was. The Caldwells had lost every material thing they had owned, although material things seemed paltry at the moment compared to the profound losses suffered by the widows and bereaved mothers and orphaned daughters who were all around them in shock, tears, or both. The Caldwells didn’t complain about the strange garment and gratefully let Alden wear it. It was no doubt heady to have rubbed elbows with Molly Brown as well. Sylvia was well aware of social status, and meeting the famous Mrs. Brown was something the Caldwells would never forget.

Thinking of the gold and jewelry she and Albert had left in their trunk, Sylvia noted that few of the Titanic’s women now aboard the Carpathia had any money on them, and those who did had only a little. “Nevertheless,” she said, “I saw women who had but five dollars [$110 today] themselves, all they owned in the world, going around and buying for those who had not a cent.” Toothbrushes sold out right away, noted Mary Hewlett.

The Titanic’s survivors had to be organized on the Carpathia to fit everyone in. That night women with babies, Sylvia and little Alden included, were given blankets so they could sleep on the floor of the dining room. That arrangement continued for the next three nights, although it was none too restful. They had to get up at 5:30 A.M. so that the Carpathia’s crew could ready the dining area for breakfast. Sylvia didn’t complain, however, and neither did the other mothers on the dining room floor. “Always I saw the tired, heavy hearted rise, most of them with a smile,” Sylvia marveled.

The women on the Carpathia “gave away all the clothing they could spare and more too,” Sylvia noticed. One gave soap, hair pins “and [found] the mother with the suckling child and to her she would give fruit and milk.” Perhaps this was Sylvia herself, as Alden was one of the youngest survivors. “The hearts of humanity were opened,” Sylvia noticed. Then, casting her missionary’s eye on the situation, she added, “God was working in a mysterious way.”

Albert “camp[ed] in a chair and got what sleep I could,” he recalled, which was not too much. To while away time, he picked up a pen and wrote a letter to someone who was on his mind: Dr. C. C. Walker back in Bangkok. It was Walker who had ordered Sylvia home against the opinion of the chairman of the mission, R. C. Jones, and four others. Walker had been a true friend to the Caldwells, despite the predicament they now faced. Albert wrote:

Royal Mail Steamship Carpathia

Dear Folks,

Here we are safe. We were one of few families who kept together when the Titanic went down. Hundreds of lives were lost, mostly men. Nearly all the women and children were saved. The trouble was, no one realized the danger, and thought this “largest boat in the world” would not sink, and if she did it would take many hours.

She struck the iceberg at midnight and in a little over two hours she was at the bottom.

We were picked up by this boat at daylight. The ocean was as calm as a lake, while we were in the life boats.

As the people did not realize how quick she would go down, there was no hurry and the life boats were not full enough. Some of the boats went down with the ship and there were not enough boats in the first place. The Titanic was considered a “non-sinkable” boat.

We were 1500 miles from New York. This boat was bound for Gibraltar when she picked us up, but she turned around and is taking us to New York.

I understand that about 700 were saved. There are many, many wives who have lost their husbands.

We are very very thankful to God for his “Goodness” to us and know that it was the prayers of our loved ones and friends that saved us.

It was a sad sight to see that beautiful ship go down and awful to hear the shrieks of the hundreds who were dying.

It was a terrible night and one that I will never forget.

The names of the survivors were sent to N.Y. so we hope that our folks have heard of our safety, as they knew we were on the Titanic.

Address us

c/o Rev. W. E. Caldwell

Biggsville,

Ill.

Sylvia and Alden are well and we are so happy & thankful.

Yours Sincerely,

A. F. Caldwell

The letter was powerful in its simplicity, the stark first retelling by Albert of a story he would repeat over and over again for the next sixty-five years. Interestingly, he identified Sylvia as being well, no doubt a reference to the fact that she had escaped the wreck, but also unconsciously pointing out why R. C. Jones had insisted on a medical examination for Sylvia behind the Caldwells’ backs. One wonders today if the “Folks” to whom the letter was addressed meant all of the missionaries (Jones included) or only Dr. Walker and his wife.

Back in the States, the Caldwells’ family had not heard they were saved. Albert’s cousin, Dr. Charles Swan Caldwell, told the Pittsburgh Post that he feared his cousin and wife had not survived. William and Fannie Caldwell, frantically scanning their local newspaper on April 16, were horrified to see their son’s name was not on the “saved” list, nor was Sylvia’s name nor baby Alden’s. But it was only a partial list. They got back down on their knees, not knowing if they were praying for the living or the dead. The next day, thank God, Albert, Sylvia, and Alden appeared in the list of those saved. Meanwhile, Sylvia’s mother had no idea they were on the Titanic until she saw an “A. Caldwell” on a list of people saved. It “awakened the anxiety of Mrs. Harbaugh for a short time, [but] she soon dismissed the idea of her daughter or son-in-law being on the ship,” a Colorado newspaper reported. Mrs. Harbaugh found out the startling news that “A. Caldwell” really did refer to her family when she got a cablegram from Sylvia saying they had been picked up by the Carpathia and had arrived safely in New York.

The relatives weren’t the only ones who were anxiously reading the lists of survivors. Numerous Park College graduates lived in New York, and more were attending a Conservation Congress meeting in town. Word spread amongst them like a Missouri prairie fire—the Caldwells were among the saved and were headed back to New York via the Carpathia. They probably found out the Caldwells had been on the Titanic through H. B. McAfee, the treasurer of Park College himself, who was in town. McAfee’s brother Cleland was on the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions, and Cleland probably knew what ship the Caldwells were on, since the Board was supposed to pay for their transportation. It would have been easy for Cleland to tell H. B. about the Park grads’ rescue. H. B. McAfee promptly began finding out how to meet the Carpathia when it arrived. Two more Park grads and old schoolmates of the Caldwells’, Jack Carlisle and Luther Bicknell, came over from Princeton, New Jersey, where they were in McCormick Theological Seminary, also eager to meet their old friends.

But first the Carpathia had to retrace her route across the Atlantic and get back to New York. It was not a pleasant trip; in fact, it was “a slow, hazardous trip—it was stormy all the way to New York . . . but we were safe,” Albert commented. Maybe Sylvia was seasick again during the storms on the cramped Carpathia, which probably rolled and pitched just as she had feared back in Naples. As fellow survivor Marie G. Young said, “The last few days of the voyage were taxing because rain kept the passengers crowded in the library, the wail of the foghorn sounding continually.” The ship finally entered New York late at night on April 18. Albert was astonished by the reporters who lined the Hudson River, shouting questions in the pouring rain and the dark. As the Carpathia slid toward its dock, people lining the bank of the river kept calling, “How many were saved? How many were saved?” Albert reckoned he heard that question shouted fifty times from the bank. All throughout the Carpathia’s sad return voyage, people ashore telegraphed survivors, and the crew doled out the messages as the ship entered the harbor in New York. “And,” Sylvia noted sadly, “as the names of some were called, they rushed eagerly forward, hoping, yes sure, that it was a message from their lost. I can see a woman now, as her name was called, press her hands together and raise her hands to heaven and say, ‘My God’ in a tone as tho she was giving thanks that her husband had been saved.” However, no other husbands had been saved. “It was but another disappointment,” Sylvia grieved.

As they prepared to get off the Carpathia, “An amusing but pitiful incident,” as Sylvia described it, served to illustrate how bedraggled the formerly prosperous middle-class Caldwells looked. “We all had tried to fix up as best we could. I had the little coat, made of the steamer rug on my baby and a dirty blanket over his head. Poor darling, he looked like a little Italian immigrant,” Sylvia said. She had been given a few necessities, which she had tied up in a donated colorful shawl, “and with this in my hand, I looked as tho I might well be the mother of an Italian baby.”

Sylvia recounted, “Two steamship inspectors came into the second cabin dining room [aboard the Carpathia], looked around, scowled and said, ‘Is this steerage?’” Sylvia laughed halfheartedly. “I don’t blame you for asking that,” she said, realizing indeed how far she had fallen in terms of prosperity. This was a bad-tasting experience for Sylvia; in the eyes of most Americans of the era, Italians were undesirable immigrants. Having been middle-class tourists a few days before, the Caldwells truly had come down in the world.

No matter how bad they looked, they were grateful—so grateful—to be setting foot on American soil again.

But a possible menace was also waiting there on that blessed American soil. According to one estimate, 25,000 people were milling about the pier where the Carpathia was expected, hoping to catch a glimpse of the survivors. Three hundred policemen cordoned off the pier from the crowd. The oglers weren’t the problem for the Caldwells, however; their would-be menace was, in fact, cleverly disguised as a mission of mercy. Thirty-five ambulances were waiting for the Titanic’s passengers as they disembarked. The ambulances had to force their way through the crowds by ringing gongs, and then the vehicles got to drive onto the cavernous dockhouse, a covered affair that had been cleared out to receive the Titanic’s passengers. The door was shut behind the ambulances. Because the mayor had ordered police to keep newsmen from communicating with passengers, an enterprising writer trolling for famous people to write about turned to the ambulances instead. He asked a pastor waiting with a private ambulance whom the ambulance was for. The pastor was the Presbyterian Reverend Dr. William Carter of the Madison Avenue Reformed Church, who told the writer that the ambulance was reserved for Miss Sylvia Caldwell. “Who is she?” the writer must have asked. Carter replied that Sylvia “is known in church circles as a mission worker in foreign fields.”

In reality, of course, Sylvia was hardly known by anyone as a “worker.” Officials in the Foreign Missions Board office in New York mainly knew her as someone who had not worked in a year. Missionaries in Siam suspected her of skipping out on her duties and illicitly squirreling away money to come home before her contract was up. Carter’s answer, therefore, seems a tad disingenuous. Could he have been sent with the ambulance to take Sylvia for the diagnosis R. C. Jones had advised?

Carter may have been doing just that. The New York Herald also ran a write-up of Carter’s attempt to pick up Sylvia, revealing a no-nonsense purpose. The Herald reported, “The Rev. William D. Carter, pastor of the Madison Avenue Reformed Church, was at the pier with a private ambulance awaiting Miss Sylvia Caldwell, one of the survivors. She is one of the Church’s foreign mission workers. Miss Caldwell will be taken directly to the Presbyterian Hospital.”

To a casual reader of the Herald, this looked like an act of compassion, the church racing to the aid of one of its own. The casual reader would have nodded in sympathy. However, the casual reader had not seen R. C. Jones’ recommendation that Sylvia be examined by church-appointed doctors before settling the Caldwells’ account. The fact that in neither interview the pastor mentioned taking Albert and Alden along hinted that Sylvia was destined to go without the pleading young husband or the appealing young baby to intervene in a diagnosis, even though Albert and especially Alden might have needed medical attention after the dire circumstances on the open sea. For that reason it seems the ambulance may have been scheduled before the Caldwells had ever been caught in an open lifeboat mid-Atlantic. Likewise, Carter’s identification of Sylvia as “Miss Sylvia Caldwell” made it sound as though she were not married; she would normally have gone by “Mrs. A. F. Caldwell.” It does seem Albert was deliberately being excluded from Sylvia’s medical exam.

Perhaps, then, it was fortunate for the Caldwells that there was someone else waiting for them inside the pier enclosure besides Carter and his ambulance. H. B. McAfee had been allowed into the Cunard Line’s dockhouse to meet them as a “relative.” He wasn’t really related, but Park College had meant so much to them both that he might as well have been. He arrived at the dockhouse an hour before Carpathia reached her destination. “A crowd of more than three thousand persons were gathered at the dockhouse, whiling away time by inventing various rumors as reason for the ship’s delay,” he said. For one thing, the Carpathia stopped at the White Star Line pier to return the Titanic’s lifeboats—the only sad remainder of the ship. As McAfee told it, the rumor went around “that Titanic’s dead were being carried ashore in that manner.” And then another rumor circulated, saying that a deadly strain of measles had broken out among the Titanic survivors on the Carpathia, “and the dead from this malady were being sent ashore. This was believed until the Carpathia moved to dock.”

The gossip ceased as the Carpathia came into view. “The crowd held its breath in an agony of suspense,” McAfee said. Some of the survivors had to be carried down. “Cries of recognition”—and surely relief—“heralded the appearance of each Titanic survivor on the gangway.” McAfee was impressed with the “true chivalry and unselfishness of an American crowd” as the simultaneously joyful and sad disembarking began. “Each individual of the throng was desperately eager to meet his or her own relatives or friends,” he said. “Yet when someone in a far away corner saw a friend in the gangway, the members of the crowd fell back and made wide lanes for the friends to meet each other as swiftly and with as little hindrance as possible. There was no hurry, no rush, no selfish surging toward the gangplank. Everyone seemed overjoyed that any other person should have found his beloved.”

The survivors were assigned to gangways based on class, so McAfee was stationed near the second class gangplank. There were some horrible moments there. McAfee described one of them:

A lone woman left the ship and as she appeared on the [gangplank] her husband called, “Thank God, my wife is saved.” As she approached within, he anxiously inquired about the two little ones with her. “They were lost,” she told him. And that great strong man, with a cry that seared every heart in the dockhouse, crumpled to the ground in a dead faint . . . The men of that crowd wept as bitterly as did the women.

After awhile the Caldwells emerged—a family intact. The three clung together, grateful to see McAfee—perhaps more grateful than McAfee knew, as he provided cover from that waiting ambulance. McAfee took them to a hotel, the Chelsea. By that kindness, Sylvia avoided Carter and an examination that had possibly been ordered with a view to reclaiming the family’s expensive, expensive journey from Siam to America. Even if the Caldwells had still had the $100 ($2,183 today) in gold, the money would not have covered even the Titanic ticket ($2,919 today), much less the voyage to Singapore, the passage through the Indian Ocean and the Suez up to Naples, the train tickets and housing and food bills through Europe to London. And Carter had no way of knowing that they had not taken their savings with them off the Titanic. The now penniless Caldwells would have needed years to pay off the bill for the trip.

But perhaps Carter was not there to expose Sylvia as a fraud or a hypochondriac. Perhaps the ambulance was sent on a true mercy trip to help a sick missionary recover; indeed, Carter was known as a crusader against pastor burnout, and tending to Sylvia could have been part of his crusade. In fact, as Albert recalled it when he was well into his eighties, “Of course the missionary society met us there and took us to a hotel.” Perhaps H. B. McAfee had been sent by the Board of Foreign Missions to collect the Caldwells and get them to a hotel, and no one bothered to tell Carter of the duplicate effort. Or perhaps Carter was deliberately standing by to aid McAfee, should Sylvia be very ill. The Carpathia did make land at night; perhaps Sylvia did not deliberately avoid Carter but simply missed him in the dark. As McAfee reported, there were 3,000 people waiting in the enclosed area; it would have been easy for any two of them to miss each other.

Any of those scenarios could well be true. However, the circumstances at least made it appear that the Board of Foreign Missions had indeed heeded Jones’s suggestion, as chairman of the Siam mission’s Executive Committee, that Sylvia be scrutinized. Having followed the Conybeare saga, having been condemned for saving their travel money, having seen Sylvia’s diagnosis voted down by five fellow missionaries (including the chairman), the Caldwells might well have known or guessed that they were under surveillance, and they gratefully fell into McAfee’s unsuspecting arms. Or perhaps McAfee, a loyal Park College friend tipped off by his brother Cleland, was protecting Sylvia from an examination designed to ensnare them.

It was probably a good thing that Sylvia was not whisked off to be examined the minute she returned, because she was so relieved that she appeared momentarily to be OK. Joseph E. McAfee, brother to H. B. and Cleland, lived in Brooklyn. He wrote to their brother Lowell, who had long ago recommended Albert for the job in Siam, “I have never known this city to lie under such a pall as that caused by what one of the papers called ‘The Titanic Tragedy’. The Carpathia docked last night, and the adjacent streets were a sight to behold. The Caldwells were able to go directly to a hotel. All seemed in good health and remarkable spirits considering their terrible experience.” But shortly the trauma of the voyage or the lingering tropical malady overwhelmed Sylvia. Joseph E. told Lowell,

Mrs. Caldwell is reported ill today, has been under a physician’s care and has seen very few persons. The baby is apparently in very good health . . . We think and speak of little else than the tragedy between items of routine business. Politics and baseball are apparently forgotten by the whole population, and the newspapers have scarcely anything to say of them or anything else except the disaster.

Thus, Sylvia finally did go under a doctor’s care in New York, and even if the physician was charged with second-guessing Walker’s diagnosis back in Siam, the trauma of the Titanic had wiped out much of the logic behind a second diagnosis such as Jones had advocated. Sylvia by now could have been suffering from neurasthenia or nerves or shock or the effects of the dire cold or the effects of prolonged seasickness. The ordeal of the escape around the world had taken its toll, and it would have been a surprise if she weren’t exhibiting symptoms of some sort.

And indeed, the church would have made deep trouble for itself by pursuing Titanic victims and money that had gone down with the ship. Such a story, had it gotten out, would have made the church look thoughtless at best, demonic at worst. The only answer was to let the matter drop. The Caldwells’ debt, such as it was, had been wiped clean. The sinking of the Titanic had effectively nullified any claims of the Foreign Missions Board against the Caldwells.

It all came out even. The Caldwells’ savings, which had cast so much suspicion on them, had gone to the bottom of the Atlantic. If their debt was cancelled, so were their tainted gains.

When they arrived in New York, Albert, Sylvia, and Alden had nothing but the rumpled clothes on their backs. After two and a half years of ministering to the poor and spiritually lost, the Caldwells were poor and perhaps feeling spiritually lost themselves. However, friends and strangers pitched in to furnish them with material things. Mrs. Wallace Radcliffe, a church worker in Washington, D.C., pleaded to Presbyterian women in her area to donate to the Caldwells, and she would see that the money got to the family in New York. A Washington newspaper joined in the appeal by noting, “When the Titanic sank Mrs. Caldwell lost all of her baggage and money, and when the Carpathia docked the couple were penniless.”

That appeal and other efforts on the Caldwells’ behalf relieved their situation momentarily. “The best of every thing was provided for us,” Sylvia said. “We were all clad in new and pretty clothing. My baby who only had a nightie and a coat made out of steamer rug, was given a complete out-fit.” A women’s missionary magazine commented, “Loving hands provided for their every need when they reached New York.” Albert had hastened to telegraph to his parents that they were home and alive, and no doubt their families were gratefully gearing up to do all they could to help.

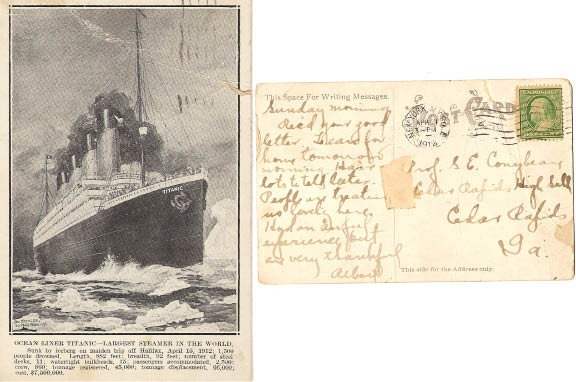

Another person Albert contacted was Sam Conybeare, who had written a letter to the Caldwells, perhaps addressed to them in New York after the Conybeares heard about the shipwreck. In replying, Albert found out that entrepreneurs worked fast in New York; someone had already printed up a postcard depicting an artist’s rendering of the Titanic cutting through the waters of the Atlantic, perilously close to an iceberg. “Ocean Liner Titanic—Largest Steamer in the World,” the front of the postcard read. “Sunk by iceberg on maiden trip off Halifax, April 15, 1912; 1,500 people drowned. Length, 882 feet; breadth, 92 feet; number of steel decks, 11; watertight bulkeads, 15; passengers accommodated, 2,500; crew, 860; tonnage registered, 45,000; tonnage displacement, 66,000; cost, $7,500,000.”

Albert got one of the souvenir cards, flipped it over, and wrote on the back to Conybeare, “Rec’d your good letter. Leave for home tomorrow morning. Have lots to tell later. People are treating us lovely here. Had an awful experience but we are very thankful. Albert.” He dropped it in the mail on April 21, less than a week after the Titanic sank. Indeed, the postcard artist had worked fast to cash in on the wreck.

The postcard, which made the disaster into a souvenir, indicated a darkly commercial side of American fascination with the shipwreck. However, mostly the Titanic’s survivors found that Americans were sympathetic and generous. A rich New York doctor stepped in to take care of the Caldwells’ shipboard dining companions, Lottie Collyer and little Madge. Unlike Sylvia, Lottie was conflicted about being saved. “Oh mother,” she wrote Harvey’s mother, “how can I live without him. I wish I’d gone with him if they had not wrenched Madge from me I should have stayed and gone with him. But they threw her into the boat and pulled me in too but she was so calm and I know he would rather I lived for her sake otherwise she would have been an orphan.” She reported to her in-laws that their host doctor had collected a good deal of money for them and “loaded us with clothes,” and a man was soon going to take her to pick up money from the funds being donated by the public.

Indeed, much was donated. The Chelsea did not charge the Caldwells for their room. Eventually, the railroad out to Illinois would give them a ticket for free. “I am sure no survivor now, is penniless,” Sylvia said gratefully a few weeks later.

Even the missioned-to back in Siam—or, rather, in Siam’s northern province of Laos—were forced to sacrifice for the well-being of the Titanic survivors. On April 19, Dr. Arthur Judson Brown, secretary of the Board of Foreign Missions, wrote to the Laos mission that the Board would not be able to provide funds to relieve malaria that was plaguing Laos. He said, “All our relief funds are now exhausted and the public appeals that are being made for the relief of the survivors and dependent relatives in connection with the steamship Titanic now sweeps all public interest in that direction.” To increase the sympathy factor, he went on, “The Rev. and Mrs. A. F. Caldwell and their baby, returning from Siam, were among the passengers on that ill-fated steamer but we are rejoiced to know that they were among the saved.”

The Reverend and Mrs. Caldwell—although “Reverend” was not actually his title—were as eager as everyone else was to learn all the details of the Titanic. Very soon after the wreck, they bought a copy of the Memorial Edition of Story of the Wreck of the Titanic. Not only did it provide a wide array of firsthand accounts, but it also featured a special introduction by the Reverend Henry Van Dyke, a well-known Presbyterian minister. The book was edited by Marshall Everett, who was billed as “The Great Descriptive Writer.” The volume, published almost immediately after the Titanic sank, was produced so hastily that the text was bound upside down in relation to the cover in the Caldwells’ copy. It gave an account of the Collyers, a fact which very much appealed to Sylvia. What was truly exciting, however, was that it mentioned Alden, if somewhat obliquely. The Caldwells’ copy was no doubt meant to be a treasure for him someday. It quoted Lawrence Beesley, who had shared the Caldwells’ lifeboat: “As the boat began to descend two ladies were pushed hurriedly through the crowd on B deck and heaved over into the boat, and a baby of 10 months passed down after them.” In his own book shortly thereafter, Beesley described two ladies, followed by the three Caldwells, including 10-month-old Alden. If Albert minded the mistake as to his gender in the Story of the Wreck of the Titanic, he didn’t say. It is likely that Everett, in his haste to produce the book, simply misquoted Beesley’s story. However, if Beesley really did at first recall Albert as female, it might have been a natural mistake in all the confusion and hubbub, as Albert was carrying the baby. Everyone seemed to remember that.

Entrepreneurs leaped into action to sell items related to the Titanic disaster. Albert acquired this card in New York and mailed it less than a week after the disaster. By the time Albert sent this postcard to Sam Conybeare, the Caldwells were looking forward to going home the next day.

The volume also featured a speech by William Jennings Bryan, whom Albert had met in 1908 when Bryan, then running for president, had arrived at Park College unexpectedly between campaign stops and had spoken extemporaneously. He had missed a train connection in Kansas City, and rather than waste time at the station, he decided to visit the college. He telegraphed ahead, and the whole town, it seemed, turned out to hear him. The Park College Democratic Club, of which Albert was a member, had their picture taken with the great man. Now Bryan and the Caldwells shared the aftermath of the Titanic tragedy as well. Bryan spoke about the Titanic at an event billed as a “memorial meeting” on Sunday, April 21, at the Broadway Theater in New York City, and perhaps Albert attended while Sylvia recovered. The theater was reportedly “jammed . . . from orchestra to topmost balcony.” Bryan called for reform in the transAtlantic passenger service, and his speech was preserved in the Caldwells’ copy of the book:

I venture the prediction that the wireless system will be made more immediately effective and efficient over a wider area and that the chance of danger will be diminished. I venture the assertion . . . that better preparations will be made with the lifeboats for the safety of passengers. I venture the assertion that less attention will be paid to comforts and luxuries that can be dispensed with and more thought given to the lives of those entrusted to the care of those shipbuilders and shipowners. I venture to assert also that the mania for speed will receive a check and that people will not be so anxious to get across the ocean in the shortest time as they will be to get across.” [Emphasis added.]

Bryan offered some good suggestions, and surely Sylvia and Albert seconded them.

Although the Caldwells were given all they could use and had lots of friends in New York who were caring for them, Sylvia reportedly lapsed into nervous shock soon after the Carpathia arrived. She had been under a doctor’s care, but the true cure was obvious: she needed to go home. She needed that rest cure that her doctors in Siam had prescribed so long ago.