9

Navigating New Waters

When Albert arrived in Richmond in 1933, he was no longer the good-looking fellow with a shock of light hair and a twinkling smile. By now he had lost his hair. He had had a mild stroke, and his mouth twisted ever so slightly. He still sported a good sense of humor and that old missionary zest for living, however. In Richmond, ever the charmer, he met a Southern girl. He was smitten. Jennie Congleton, the cute gal with the honeyed accent who had caught Albert’s eye, was thrilled to catch his as well. Jennie was fifteen years younger than Albert, but she was well into her 30s—an old maid by local standards.

Jennie had not had an easy life, although her mother, Jennie Whitley, had aspired to better. Hailing from Pantego in eastern North Carolina, Jennie Whitley had attended Staunton Female Academy in Staunton, Virginia, graduating in 1885. Certainly her parents had means and ambition for their daughter to send her to board so far from home. Jennie Whitley loved school. She took diligent class notes in appropriate parts of her Latin book, but on the endpapers of the textbook she doodled pictures and wrote of her friend Ida, “Ida and Ned Cameron will make a lovely couple.” To this Ida responded by grabbing the book and writing that somebody—his name began with J—“and Jennie Whitley are mashed on each other.” We don’t know who that somebody was, because Jennie erased his name and crossed it out. Nevertheless, she saved a lock of hair in the book, possibly that of her crush. She also kept multiple essays that she composed. In one entitled “Education,” she wrote:

Education is the wheel upon which fortune turns. Men have started out in the world without a dollar in their pockets, and have slowly but firmly risen to eminence. How: I ask. By means of a good education. Of all the blessings which it has pleased Providence to allow us to cultivate, there is not one which breathes a purer fragrance or bears a heavenlier aspect, than education.

Well-educated Jennie was interested in well-educated men, and she met one back in North Carolina, perhaps while she was teaching at Richland Academy. He was Asa Biggs Congleton, known in more alphabetical fashion as “A. B.” During his examinations to qualify as a teacher in 1881, A. B. scored 90 or 95 for every subject except Geography (he got an 80 in that) and was given a First Grade certificate, the highest designation. He studied hard and pulled his Geography grade up to a 95 in 1883. However, A. B. was not able to make a living as a teacher. After he and Jennie Whitley married, their focus on education became a distant memory. The Congletons for generations had owned a family farm near Stokes, North Carolina, and A. B. went into farming. Jennie was frequently pregnant and frequently giving birth. First came Jim, then Edwin, then Bess, and then Will. The children were all close in age, a lot of mouths to feed and a lot of bodies to clothe.

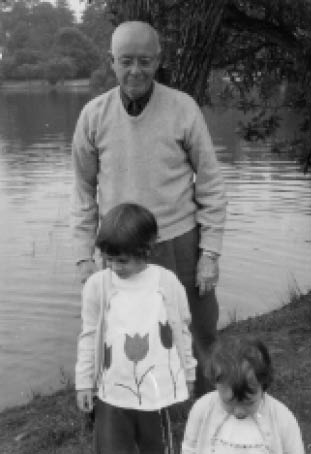

Albert after he had moved to Richmond.

In July 1897, Jennie gave birth to Miriam, who died at fourteen months. In December 1898, the family celebrated the birth of Simon, a comfort to replace the lost child—only to bury Simon at seven months. But soon Jennie was expecting again, and all the Congletons rejoiced, somewhat anxiously, in the birth of Jennie Whitley Congleton, named for her mother, on May 16, 1900. It was a hopeful way to start the new century.

The elder Jennie didn’t have much time to enjoy her little namesake, who quickly became known as “Jennie Whit” to distinguish her from her mother. Jennie became pregnant again, and this time things went tragically awry. Jennie Whit was only two when her mother and the new baby died in childbirth on March 10, 1903. Jennie Whit’s first memory was someone holding her up to a window to see her mother and the baby, stretched out on a bed in the house, awaiting burial.

A. B.’s response to the loss of his wife was to reorganize the household. Jim and Ed went to farm work. Bess, who was ten, was put in charge of the kitchen, with Will, now seven, in charge of Jennie Whit. Will wasn’t that good a babysitter. One day he decided Jennie Whit needed a walk in her carriage. He threw her into the buggy and started trotting around the outside of the house. Jennie Whit seemed to like going fast, so he went faster and faster until at last they were fairly flying around the two-story farmhouse. But then the buggy got too fast. They were coming up on a tree, and Will couldn’t turn out of the way in time. There was no choice but to save himself. He let go of Jennie Whit’s buggy and hurled himself out of the way, leaving his sister to her fate. Luckily Jennie Whit was unharmed in the ensuing crash, although Will no doubt took a licking for it. Despite the buggy crash, Jennie Whit and Will were close. Will was, along with Bess, the closest thing Jennie Whit had to a mother.

Jennie Whit is the baby in Jennie Congleton’s arms. Others are, from left, Jim, Will (wearing a skirt, as young boys did in the era), Bess, and Edwin, and father A. B.

As they grew up, in fact, Bess and Jennie (as she often called herself now) worked out an interesting arrangement: Jennie went to work and Bess kept house for her. That went well for some time, until someone challenged Bess about being an old maid stuck waiting on her little sister. “You’ll never leave this place unless you choose to leave,” a friend told her. Bess realized this was so, and she pulled up stakes and moved to San Jose, California. This brought on a radical change for Jennie, and Albert saw his chance. He began seriously courting her, having probably met her at State Farm. If Albert had been worried about entering the dating scene again now that he had lost his hair, he didn’t need to worry about Jennie’s opinion. Her beloved brother Will was bald, too.

Bess had not been in California for long before Jennie sprang the shocking news: she was thinking of marrying Albert Caldwell. He was fifty-two to Jennie’s thirty-seven, but Jennie felt sure she could count on Bess’s approval. Bess, she knew, liked Albert. Indeed, who didn’t like Albert Caldwell?

At first, her family didn’t. While they were dating, Jennie and Albert and another couple visited Jennie’s oldest brother, Jim, and his family in Stokes. The other man was young and tall and good-looking, and the family thought (or hoped) Jennie was interested in him. There wasn’t that much spare room in the house, so the family let the other man stay in a guest room and sent Albert to a boarding house in nearby Greenville. He hurried back for church the next day, too late for breakfast, and as a result ate at such an astounding rate for lunch that the slender Congletons were dumbfounded. Virginia, Jennie’s small niece, was shocked when Albert lit into her mother’s pickled peaches, a delicacy that the Congletons understood were meant to be eaten one per meal. He gobbled three.

Mainly, however, the Congletons were worried for Jennie’s sake. Albert was divorced with two nearly grown boys. He had had that stroke. And there was the fact that he was fifteen years Jennie’s senior. “You’ll spend your life taking care of him,” family members warned. When Jennie wrote home to tell everyone that she had accepted Albert’s proposal of marriage, nine-year-old Virginia wrote back that when her daddy (Jennie’s brother Jim) read that, “he got red and sweated.” Likewise, Bess wrote to Jennie from California, “I got your letter yesterday. Was quite a little surprised to know that you are contemplating matrimony. I think Mr. Caldwell is a very nice man and anyway, tho’ it is rather sudden if you should ever become dissatisfied it is quite fashionable to be divorced. Getting married is not as great a risk now as it used to be.”

There was something Jennie was worried about: Albert was so well educated, and she was not. “You speak of Mr. C. being better educated than you,” Bess reassured. “You are fairly well educated even if you don’t have any degrees. Did you see in Winchell’s column where Eddie Cantor who only got as high as the fourth grade in school was to address the Business class of Harvard University?”

Jennie and Albert were married December 22, 1936. Albert’s sister, Vera, saw to it that Jennie, who suddenly needed to figure out how to run a kitchen, got a good cookbook and a bunch of Vera’s recipes for Midwestern comfort food, ranging from Vera’s Tuna Casserole to Vera’s Apple Crisp. The happy couple wed in Richmond and as a very unusual honeymoon went to Rocky Mount, North Carolina, to admire Will’s baby daughter, Kay, now about to turn 1. Albert found a lot in common with Will’s wife, Dot, who was in-law to Jennie . . . but what was she to Albert? “I guess we’re outlaws,” he teased, and ever after, the two “outlaws” called themselves that and vowed to stick together—which they sometimes did when the formidable matriarchs took charge of pickled peaches and other matters at family gatherings.

Meanwhile, back in the Midwest, Sylvia was trying to keep a youthful Raymond on the straight and narrow. Raymond began drinking heavily. This must have been a deep disappointment to Sylvia, who had had such success guiding young men Christward in her Sunday School class back in her college days. She worried about Raymond’s drinking, as did Albert from afar. The two were proud of maintaining a friendly divorce, although no doubt even a friendly divorce was hard on their sons and contributed to Raymond’s drinking.

Perhaps to escape her troubles and to meet people after she became single again, Sylvia further developed her long interest in drama. She had started acting at Bloomington’s Community Players from the time she had moved to Bloomington with Albert, and as the marriage faltered and then fell apart, she became a regular. She played Julia Rutherford in A Little Journey, Princess Beatrice’s sister Symphorosa in The Swan, Mary Beal in If, Mrs. Pennington Brown in Lombardi, Ltd., Mrs. Platt in Up Pops the Devil, and she played a lead role in the comedy I Want a Policeman. She had quite a stage presence, resulting in excellent reviews. She was lauded for throwing herself into her part in A Little Journey, and another reviewer of A Little Journey liked her performance so well that he said, “Mrs. Caldwell’s wholesomeness in giving a sympathetic performance of her role was a beautiful piece of acting and everyone will want to see her in another community play.” Apparently everyone did want to see her in other plays. She was given a cameo publicity shot in the local newspaper when she was scheduled to appear in Up Pops the Devil, presumably because she was a good draw. Lombardi, Ltd. turned out to be one of the Community Players’ greatest successes.

Sylvia on stage in Lombardi, Ltd. with the Bloomington Community Players. She is under the “A” in “Lombardi,” playing the role of Mrs. Pennington Brown. The show was one of the greatest financial successes of the Players up until that time.

Meanwhile, Albert’s mother and sister lived in Wisconsin, and Alden and Raymond still enjoyed the family lake house in that state. Albert made treks to the Midwest to visit that branch of his family. Even when the boys were grown, though, Sylvia was the one who had to deal mostly with their concerns, while Albert tried to parent from a great distance. Alden started college at Illinois Wesleyan University in Bloomington and graduated from University of Illinois in 1933 with a Bachelor of Science degree in chemical engineering. Raymond started at the University of Illinois but graduated from Illinois Wesleyan with a B.S. in business administration in 1937. He then went into the family business for the next twenty-six years, working for State Farm. He started as a code clerk in the fire insurance division and rose through various ranks, eventually becoming an underwriting superintendent.

Sylvia was an excellent secretary, a sharp cookie in a company where most of the female staff had not been college educated nor had been around the world. She stood out among them and was highly regarded. Whereas some of the young men in the firm thought it best to act as yes-men to their boss, G. J. Mecherle could count on Sylvia to be forthright. He could run ideas by her and get a straight-up, honest opinion.

Mae Mecherle died on August 22, 1942, and Sylvia and George were married a respectable year and a half later in Hot Springs, Arkansas, on January 8, 1944. They honeymooned at the Arkansas resort, a much different wedding trip than the journey to and aboard the Manchuria for Sylvia’s first honeymoon. The fact that they married at all kept the gossips’ tongues flapping about their relationship, but never mind. The former Sylvia Harbaugh Caldwell was proud to be Mrs. G. J. Mecherle now. She loved to give out her name as the wife of the State Farm founder. She saw herself as sort of a queen of Bloomington and truly enjoyed the role. She resigned her job at State Farm when she married, but she remained a leader among her circle. Executive secretaries would take social cues from her; according to one friend, if Sylvia ordered a cocktail at lunch, they would, too, even though G. J. Mecherle himself didn’t drink (or didn’t drink in public). Sylvia was definitely independent. And she was a stylish dresser and a gracious hostess.

George Mecherle had been a happy slave to his job, so Sylvia was determined that he learn to relax. As his biographer put it, because “State Farm was George Mecherle’s one great interest in life he could hardly have chosen a more amiable or understanding companion” than Sylvia. But George was accustomed to listening to her, and she “quietly but firmly kept him from spending all his time and strength on his business affairs.” He had almost never taken a vacation, other than a fishing trip each spring with fellow businessmen. In 1948, she talked him into a real vacation, his first in many years, and their first together other than their wedding trip to Arkansas. They took a cruise to the West Indies. It was the first time George had been at sea. To avoid seasickness, Sylvia picked a very large ship, the Mauretania II. She mentioned to the captain her link to the Titanic, and he asked if she would tell the story in an on-board lecture. It was so popular that she was asked to repeat it.

Sylvia and her second husband, G. J. Mecherle, the founder of State Farm Insurance Co.

In 1949, the Mecherles went to Europe on a quest for George’s family roots. George asked a travel agent to find the village of Untermasholderbach in Germany, where George’s father, uncle, and aunt had lived before immigrating to America in the mid-1800s. Sylvia and George and two German guides researched George’s long-ago family there. Afterward they reprised part of Sylvia’s first European trip back in 1912. They went to England, although George was not so intrigued with palaces and cathedrals. He “was happiest when motoring through the farming regions,” his biographer said, and that was how he enjoyed Europe.

Stateside, he and Sylvia also spent some time at Lac Court Oreilles in Wisconsin, at the old family lake house that Albert and Sylvia had bought and their children still used.

Sylvia succeeded in getting George to enjoy life in a more leisurely way, making their all-too-brief marriage pleasant and focused differently from his first. It was different from her first marriage, too, featuring an upscale and comfortable lifestyle that she loved. George was active until the last, dying suddenly on March 10, 1951, at age seventy-three, seven years after their marriage, leaving Sylvia a well-to-do widow.

She might have lived on as the queen of Bloomington, but her life took a turn toward the national and even international spotlight in 1955, when she happened to come across an advertisement in the local newspaper. A historian named Walter Lord was seeking survivors of the Titanic to tell their story for a book he was writing, which eventually became the best-selling A Night to Remember. Sylvia answered the call. She told the story as she recalled it, traveling back mentally forty-two years or more to the mission posting in Siam, the trip through Europe, the decision to take the Titanic. She never mentioned her seasickness or the name of the illness that plagued her from Siam, nor did she discuss the symptoms that prevented her from carrying Alden off the ship. By then, neurasthenia had for many years been discredited as an illness, and it would have made her sound like a mental case to bring it up and to discuss her neurasthenia-induced inability to hold Alden, one of the critical factors in saving her first husband’s life. Nor, of course, did she open any old wounds by suggesting she had left Siam under a cloud of suspicion. Such an admission would have muddied the reputation of the queen of Bloomington. She did, however, introduce a startling quote. She described how, when the Titanic was being loaded, she asked a baggage handler if the ship was really unsinkable. “Yes, lady,” he told her, according to Sylvia’s memory. “God Himself could not sink this ship.”

Walter Lord was a careful researcher, refusing to use sensationalist details, no matter how juicy, without corroboration. Presumably he got the second witness he needed to the remarkable quote, because he used it. Maybe Albert corroborated it, or perhaps the deckhand did or someone else. In 1962, Albert recalled the quote as “Here is a boat that God Almighty cannot sink.” Some have wondered why Sylvia kept such a spicy quote quiet more than forty years, thus questioning if it had been said in quite that way or even said at all. However, there was a slim bit of evidence from 1912 that tended to confirm it. On page 5 of Sylvia’s 1912 Women of the Titanic Disaster, she referred to the Titanic as “the huge, almost defying work of man,” which indicated the Titanic was defying God. Since the Titanic in and of herself was incapable of defiance, Sylvia’s characterization of the ship as defying God indicated that she had heard someone defy God in the name of the Titanic—and perhaps “God Himself could not sink this ship” was that defiance.

No matter the exact origin of the quote, Sylvia’s recollection of it as delivered in Walter Lord’s book came to define the Titanic. The quote encapsulated and condemned man’s feeble attempts to play God in claiming invincibility and in determining who lived and died that night. It was a theme that a former missionary approved of—especially a missionary who had been buffeted hard in the storms of her own life.

Sylvia posing with her copy of Walter Lord’s famous history of the Titanic, A Night to Remember. A quote she recalled for the book, “God Himself could not sink this ship,” became world-famous.

Her place in history now recorded by Walter Lord, Sylvia reigned on as queen of Bloomington. She was active in the Bloomington-Normal Art Association. She probably continued supporting (and maybe acting in) the Community Players in Bloomington for many years. As one of the social leaders of the community, the widow of G. J. Mecherle also served on the Brokaw Hospital League and was a life member of the Bloomington Country Club. She was a member of the Order of the Eastern Star, and of course she was a member of Second Presbyterian Church.

Sylvia, still stunning, photographed in the 1950s.

Life was busy for Sylvia, revolving around her social position in Bloomington. She spoke sometimes about the Titanic and had a prepared opening and closing that she carried with her, but she gave the meat of the story from memory. Mrs. M. V. Mann, a survivor of the Titanic from Toronto, sent Sylvia a “very fine letter” once. However, Sylvia lost interest in talking about the shipwreck. The past was another husband ago, a time now captured deftly in Walter Lord’s book. She told her grandson about the Titanic only once, having gotten tired of talking about it. He didn’t pay much attention; he was just eight years old. By 1963, Sylvia confided, “My doctor has advised me not to relive my experience” on the Titanic. She refused to answer her niece’s questions about it.

Albert, on the other hand, hoped to see the old ship again and to get his gold back. The gold had long since lost its taint; he no longer felt guilty about having saved the money, if indeed he ever had. He was fascinated at a Central Richmond Association meeting in 1959 when Retired U.S. Navy Admiral Dwight H. “Rainy” Day spoke about a submarine being developed by Reynolds Metal Co. that would hopefully withstand the extreme water pressure in the deep ocean. Day commented that the submarine, the Aluminaut, might one day find the Titanic. Albert couldn’t resist the moment. “Admiral,” he said, “I’m giving you a direct order. When you find the Titanic, I want you to find the $100 worth of gold I was bringing home from Siam. It’s in the bottom of my trunk in the bottom of the Titanic at the bottom of the ocean!” As time wore on and neither the Aluminaut nor any other searcher had found the Titanic, Albert made sure the next generation would claim the gold. Jennie’s beloved brother Will had died too young, and Albert had stepped in to become a surrogate grandfather to Will’s granddaughters. The girls were enamored of the Titanic story and loved to hear Albert tell it. “When they find that boat and bring it up, you girls can have my gold pieces,” Albert often promised them. Albert used to spend long stretches of time with Lloyd Hedgepeth, who married Will’s daughter, Kay, working out the engineering of how anyone might raise the Titanic. “Do you think it’s possible they could raise it?” he’d ask. “I’d like to see it again.” Albert wondered if they could pump Styrofoam into the wrecked ship and float it. Lloyd was an engineer—not in undersea matters (he worked with the Air Force’s space program), but that didn’t stop Albert from speculating. He always knew they’d find the Titanic. He always knew they’d raise it. He hoped he lived to see the day.

Albert got to ride through Richmond with star Debbie Reynolds as an advertising gimmick for the movie The Unsinkable Molly Brown in 1964.

Albert enjoyed being a Titanic survivor. When the movie The Unsinkable Molly Brown came out in 1964, he got to ride around Richmond in a quaint Model T with star Debbie Reynolds. It was a promotional gimmick to advertise the movie, but Albert went along with it and rather enjoyed being seen riding with the famous and beautiful Miss Reynolds in her fur stole and white gloves, while a costumed chauffeur drove them through downtown. Albert saw the movie, too, and could quote every detail of it for the next dozen years. It was remarkable that he had met the real Molly Brown so long ago when she gave Alden a funny little garment to keep him warm on the Carpathia. Alden was now fifty-three.

Other than Sylvia and Alden, Albert never contacted another survivor until the early 1970s. He got in touch with a man who had been twelve at the time and who happened to be touring Virginia. And another survivor contacted him—a man from nearby Norfolk who was just a few days older than Alden. “Had an interesting visit with both,” Albert reported in a Christmas card to Titanic historian Ed Kamuda.

During his life in Richmond, Albert became an elder in Grace Covenant Presbyterian Church and a member of Dove Masonic Lodge. After he retired from State Farm in 1958, he and Jennie moved into a retirement apartment in Richmond, and he served as president of the Richmond chapter of the American Association of Retired Persons. He entertained the retirees in his complex with things they might remember from the past—the Titanic, of course, but also “O, the Mistletoe Bough.” Once an elderly lady remembered the creepy song fondly as an old favorite in her childhood. That pleased him a great deal. He also took up the ukulele, which he played enthusiastically.

He spoke about the Titanic to schools, lodges, church groups, clubs, whoever asked, and he never charged a fee—he was proud of that. Of course, he had charged to speak back in 1912 on the Chautauqua circuit, but those days were so many careers ago. Now he never charged, considering the telling of the Titanic story to be something of a public service. Near the end of his life, a church from the rougher side of the tracks with an all-black congregation asked him to speak. It seemed on the surface a scary proposition for an old man well into his eighties. “So I told them I’d do it for $25,” he confided to his great-niece. “I thought they’d turn me down.” But who wouldn’t pay $25 ($123 now) to hear a Titanic survivor? The congregation came up with the money happily. “And you know what?” Albert said. “They were the nicest people I ever spoke to. Taught me a lesson!”

Jennie sometimes tagged along with him as he gave his speech, always having to fight the battle of explaining that she herself was not on the Titanic; that was the first Mrs. Caldwell. “Has anyone ever heard a survivor of the Titanic speak?” Albert would open the speech, and Jennie would grin wryly and raise her finger slightly, just out of Albert’s range of vision. A talented artist, she once painted a picture of a ship leaving port, evocative of the Titanic, with the inscription, “Should auld acquaintance be forgot?”

Jennie Caldwell, who got pretty tired of hearing about the Titanic, painted this scene of a ship leaving port, likely meant to be evocative of the Titanic, although it was not an exact likeness.

Albert wrote to his sister, Vera, once a week in Wisconsin. He visited Wisconsin from time to time, where he helped Vera keep her house up, clipped favorite Midwestern recipes for Jennie, and kept up a chatty correspondence via mail with his wife. He was prone to write goofy love poems, too:

Here I am in Old Wis

And My dear wife I do miss.

But I’ll soon be back

In our little shack

And give her a great big Kiss.

Heaps of Love

Your Hubby

When Albert wasn’t visiting in Wisconsin, he was taking Jennie to various exotic destinations—the Holy Land, St. Augustine, Europe—and they even got to Italy, now cholera-free. These were places a small-town North Carolina orphan girl would never have dreamed of going. Her mother would have been thrilled. And Jennie need never have worried about her lack of education. She and Albert turned out to be a perfect match.

Albert and Jennie Congleton Caldwell at St. Augustine, Florida.

Back in the Midwest, Sylvia’s health began to fail. She went into the Brokaw Hospital in Bloomington in November, 1963. She lingered for fourteen months, never leaving the hospital. Around New Year’s, 1965, she had a stroke and then contracted pneumonia. She died January 14, 1965, at age eighty-one at 12:36 A.M. The Reverend Russell Shaw preached her funeral the following Saturday at the Metzler Memorial Home, and she was buried in Bloomington in East Lawn Cemetery. Albert outlived her by a dozen years.

Albert became the surrogate grandfather to Will Congleton’s grandchildren. Pictured here in Rocky Mount, N.C., circa 1965, he watches over two of them.

Contrary to all predictions in 1936, Jennie never did wind up taking up care of Albert; he wound up taking care of her. Jennie’s delicate health, exacerbated by smoking, began to fail. Albert, then ninety, took great care to make her walk in the halls of their retirement complex every day. He himself did “squats” and other exercises in the hall each day to keep limber. His “outlaw,” Dot, also in failing health, wrote him for his birthday in September 1976. He replied on the day he turned 91:

Jennie is about the same . . . I cook her a good breakfast and bring her a good meal, from the cafeteria at noon . . . I make her walk, up and down the hall, every day . . .

I am feeling fine and glad to be alive. My Mother died on her 91st birthday. She was incapacitated for the last ten years of her life and died in a Nursing home. If I can keep well for a few more years, I know I will not have to be in a Nursing home very long.

With Love,

Al

He had always joked with Dot about the “outlaws” sticking together, and in the end they did. Both of them died on the following March 10, Albert in the morning and Dot that afternoon, twenty-six years to the day after Sylvia’s G. J. had died and seventy-four years to the day from when Jennie Whitley Congleton had died in childbirth and left Jennie motherless. And now Jennie was alone again. It was a strange coda to two families divided and united by divorce and remarriage. Jennie’s family buried Albert in a place he had never lived, Greenville, North Carolina, near her childhood home, on March 14. Mourners heard a service at Grace Covenant Presbyterian Church in Richmond at 10 A.M., and the service changed states with the burial at Pinewood Memorial Park in Greenville that afternoon at 3:30.

Albert as an old man, caught in a serious moment.