1

Of Those in Peril on the Sea

Albert Francis Caldwell, twenty-six, shifted his baby son to one side and peered over the steep side of the ship into . . . nothing. He could see the vertical hull as it slithered into empty darkness, but he couldn’t even make out the water below. It was utterly black, void—and, well, puzzling. With baby Alden squirming against the cold night air, Albert wondered why they would be putting women and children off in the lifeboats?

Albert tested the ship beneath his feet, one of those things you do unconsciously every time you step on deck, but this time he thought of it. It was, as his unconscious feet always read it, solid. It wasn’t listing. Clearly the ship could not be in any danger. If it were sinking, he’d have tripped over a sloping floor. He’d have heard the rush of water or the screams of panic—all those things you imagine would be evident on a sinking ship. Not one was happening. Clearly, he thought a little crossly, this was a case of overcautious behavior that could result in raw tragedy. Put women and children off in an open boat into an ocean blacker than coal? What a stupid idea!

Albert’s thoughts flew to his wife, Sylvia Mae Harbaugh Caldwell, twenty-eight, and to the little son in his arms, Alden, who had turned ten months old just four days before—no, five days, as surely it was now after midnight. Sylvia was getting over a dire illness and was prone to nausea. If she got into an open boat in the Atlantic, she’d become seasick. And the baby? Their precious Alden was small enough to need constant attention, and at this sleepy hour of the night, they hadn’t been able to find the key to their trunk —and Alden’s warm things were locked in the trunk. Thus the baby was wrapped in a steamer rug. It was warm enough, but it was not his own little coat. Sylvia couldn’t even hold the baby properly, owing to the illness she was still battling. The thought of putting the baby on a lifeboat in this bitter cold without his coat when his seasick mother couldn’t really hang onto him—well, it was preposterous.

It was obvious to Albert what they needed to do. He had made his decision. He would not put his wife and child off on the lifeboat. They would stay on the Titanic.

In the two and a half short years of his married life and career, Albert Francis Caldwell had worn various hats—husband, missionary, teacher, father. On this unforgivingly bitter April night in the North Atlantic Ocean, he was looking at the situation entirely as a good husband and father, protecting his wife and child. What he didn’t realize, as he shivered to a decision in the darkness, was that the hat he needed to be wearing that night was his missionary one. Because at the moment of that fatal decision, what the Caldwell family needed more than a husband or a daddy was a guardian angel—a sweaty, grimy guardian angel covered in coal dust.

If any couple were equipped to recognize a guardian angel, it should have been Albert and Sylvia Caldwell. They had prepared for as long as they could remember for this moment—this critical snap of God’s fingers when they needed to recognize miraculous intervention the instant it happened.

Albert was the son of a Presbyterian minister. In fact, the Reverend William Elliott Caldwell was waiting for them at home in Biggsville, Illinois, where he was shepherding the latest in a long string of small churches he had pastored throughout the Midwest. Albert’s mother, Fannie, was also waiting, anxious to meet her grandson for the first time. She was named Frances, or “Fannie,” after her parents, Francis P. and Mary Frances Gates. William E. and Fannie had named their son Albert Francis for his grandparents and his mother. Born September 8, 1885, at Sanborn, Iowa, Albert was their first child and would be their only son. He contracted pneumonia when he was a toddler but pulled through that, God be thanked. He hadn’t really been sick since, another thing to glorify God for. Little Albert seemed on track to follow in the family business, the ministry. He joined the church when he was a small boy.

Albert Francis Caldwell as a baby in Iowa.

For Albert’s first birthday, he got, of all things, a baby girl named Stella Dennis, also born September 8. He didn’t know her just then; she was born in Kansas and had not actually met anyone in his family yet. However, by the time she was eight she had come to live with them in Allerton, Iowa, after her mother, Caroline Howard Dennis, had died young, and her father, Henry Clay Dennis, had given her up. Caroline had managed to leave her daughter some property, probably jewelry, that was valuable enough to be taxed. William and Fannie didn’t let that fact go to Stella’s head. They established important routines at home, such as getting down on the knees every night to pray for God’s grace for loved ones. By 1895, Albert and Stella had a new person to pray for, Albert’s cute baby sister Vera, who for once did not arrive on September 8.

William and Fannie Caldwell at their home in Iowa. Blurred at the bottom are (probably) Albert and Stella. Stella D. Caldwell’s exact relationship to the William E. Caldwell family remains a mystery.

But Albert’s and Stella’s and Vera’s growing-up years weren’t entirely taken up in seriousness and Bible-reading. There was fun in the household, too, including lots of music. A particular favorite was the old English folk song “O the Mistletoe Bough.” Albert loved singing the deceitfully holiday-spirited lyrics:

The mistletoe hung in the castle hall,

The holly branch shone on the old oak wall;

And the baron’s retainers were blithe and gay,

All keeping their Christmas holiday.

The baron beheld, with a father’s pride,

His beautiful child, young Lovell’s bride,

While she with her bright eyes seemed to be,

The star of the goodly company.

O . . . the Mistletoe bough!

O . . . the Mistletoe bough!

In the ballad the young bride suggested they play hide and seek, but Lovell, alas, could not find her, nor could anyone else . . . and they never did. Lovell aged to old manhood, broken and weeping for his lost bride. The song went on:

At length an old chest, that had long lain hid,

Was found in the castle. They raised the lid,

And a skeleton form lay mouldering there,

In the bridal wreath of a lady fair.

Oh, sad was her fate! in sportive jest

She hid from her lord in an old oak chest;

It closed with a spring! and her bridal bloom

Lay withering there in a living tomb.

Albert leaned into the eerie, unhappy refrain one more time, perhaps making little Vera shiver:

O . . . the Mistletoe bough!

O . . . the Mistletoe bough!

The children may have read Parlor Amusements for the Young Folks, and if so, the book gave step-by-step directions for acting out the Mistletoe Bough story. Perhaps Albert and Stella played the tragic roles for William and Fannie and little Vera. The book warned children that the girl playing the bride was to hide in a box that was held together only by hook-and-eye latches. This was ostensibly so that the “bride” could be replaced by “mouldering” flowers at the end, although the real object was to keep from repeating Mrs. Lovell’s unhappy demise.

Pastor Caldwell didn’t make all that much money, but there was enough to hire a live-in housekeeper, Elsie B. Able, just two years older than Albert. Also in the family was Fannie’s father, Francis Gates, who lived with them. The three Caldwell children learned with some pride that a Caldwell ancestor had, generations back in the family tree, married into the family of the famous Pilgrim John Alden. It was a family legend that got told around, but no one really knew for sure if it was true. Still, Albert was proud of it.

Albert and Stella shared something else besides their birthday and their household; William’s wandering career resulted in the twin-like pair enrolling in high school at the same time, despite the year’s difference in their ages. By then the family had moved to Breckenridge, Missouri, in the coincidentally named Caldwell County. Breckenridge was “a hustling little city” of 1,200 people, conveniently located on the railroad and “surrounded by as fine prairie land as the eye could wish to see,” bragged a county directory of the era. As one observer put it, the town of Breckenridge had “made a steady, though not rapid growth.... Breckenridge has, however, in the past few years awakened to the necessity of doing things.” Just about the time Albert and Stella left home, the town created a “nice park with grand stand and paved walks and a goodly lot of granitoid walks and crossings.” The town even boasted telephones, and the year after Albert and Stella went off to college, city voters approved $10,000 (the equivalent of $243,417 in today’s dollars) in bonds to build an electric light plant. Whereas Albert and Stella had studied by flame light, young Vera would have electricity.

Reverend Caldwell pastored the Presbyterian church in Breckenridge. The congregation met in a frame building and had “a fair membership,” as the county directory described it. The good pastor had a lot of competition in converting and comforting souls. The biggest church in town, the Christian church, featured an impressive brick building. The Methodist Episcopal church was smaller but still had an enviable congregation of a hundred people. There was another Methodist Episcopal church in town, plus Baptist, Congregational, and Catholic churches. The town featured seven men’s clubs and one women’s club, and if Albert hadn’t been intended for the ministry or some other sort of church work, he might have grown up to work for the town’s self-made entrepreneur, Mr. Ward, who ran a furniture factory.

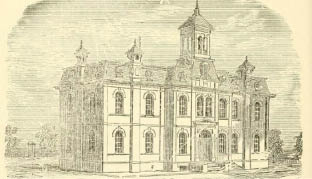

The Caldwell children were enrolled in the Breckenridge school, a two-story brick affair that flamboyantly featured four smaller bell towers and one huge one, with arched windows and a mansard roof. There were 240 students divided among six teachers, and in 1904 there were fourteen high school seniors. The school served a small town, but it had a curriculum that seemed worthy of any city. Stella reported her course work as:

Higher Algebra, Phillips and Fisher’s Plane and Solid Geometry, Collar and Daniell’s First Latin Book, 4 books of Caesar and 4 Orations of Cicero against Citaline. One year of Higher English and one of Rhetoric. Elements of Physical Geography and Geology, Meyers’ General History and English, History by Lancaster. American Lit. (Simon and Hawthorne’s) and Painter’s English Literature. Part I of Crocket’s Trigonometry. One year of Civil Government.

The school was imbued with the forward-looking spirit of the frontier that tended toward gender equality. Girls at Breckenridge High took just as much charge of class business as boys—in fact, even more than the boys. This was the twentieth century, after all. Lenora Reynolds was the class president, with Stella serving as class secretary and Ethel Cox handling the class’s money as treasurer. The only male officer was Eugene W. Robinson, the vice president.

Breckenridge School’s high school department was run under the watchful eye of Principal G. W. Sears and teacher Carrie Kelley. Vera was enrolled in the lower grades under the tutelage of Mrs. Helen Kirtley. The best part, however, was that Superintendent Nelson Kerr was an advocate of playgrounds and playtime for schoolchildren as part of the normal school day. Kerr believed that play built character in children. Play, he was convinced, kept down thievery and mean-spirited pranks, a theory he was eventually lauded for in a national education magazine. “Do you know, since we have had play as part of the work in the Pitman School [with Kerr as principal] that there have been no gangs of boys on the streets at night?” a banker in Kirkwood, Missouri, exulted eleven years later. “They used to break windows, jeer at passersby and destroy property in various petty ways.”

The Breckenridge school.

Accordingly, the school in Breckenridge offered healthy fun as well as work. Albert and Stella studied under that strenuous curriculum but also enjoyed the more pleasant aspects of education. Albert was a singer, good enough and confident enough to perform a vocal solo during one of the graduation events their senior year. Stella read the Class Will as part of the festivities, while classmates Ethel and Minnie Cox performed a “Comedietta” entitled “Graduating Essays.” The school had an orchestra, which played in honor of the graduates on Class Day. All fourteen seniors performed the class song and took part in a pantomime.

Albert himself prepared an oration, “Night Brings Forth the Stars.” The speech doubtlessly spoke of the outpouring of star power from the class itself. The Class Prophecy, delivered by Wynne Curran, probably did not foretell tragic decisions regarding lifeboats in the mid-Atlantic, although no doubt it did anticipate success and great futures. Curran himself went on to study engineering. Classmate Joseph Howard Peck became a doctor. As the Class of 1904 set forth into the world, the future took on the sparkle of the new century as predicted by the title of Albert’s speech.

The Class of 1904 of Breckenridge School chose blue and white as their class colors—the colors of puffy clouds and the vibrant sky hovering above the green hills of Caldwell County—and the violet as the class flower. Albert, however, did not intend to stay amongst those green hills. He had spent his childhood moving about, and he was not sentimentally tied to the place. He intended to get a college education, even though his parents didn’t have enough money to pay for a typical college course. Albert already knew how he’d lick that problem. He would work his way through Park College, the Presbyterian school that took in penniless (or practically penniless) students. It was only eighty miles away by railroad, but ultimately it would take him around the world, concluding with a catastrophic trip on the Titanic.

Meanwhile, Sylvia Harbaugh was on a similar trajectory. She, too, was the daughter of a devout Presbyterian family, and according to one source, her father, Chambers C. Harbaugh, had been born in China, which indicated he was a missionary’s son (even though the U.S. Census persisted in reporting he was born in the very ordinary location of Pennsylvania). He had been a drover when he was a young man but later was an oil company salesman and now was a clerk in Glenshaw, a rural suburb of Pittsburgh. Sylvia was born in Pittsburgh on July 23, 1883 or 1885, the second of five children, four of them girls. Her older sister was Alice; then there was Sylvia, who was named for her mother; followed by younger sister Beatrice. Then came brother Milton, and finally little Eva.

Alice started school at the old Shaw Mill building in Glenshaw, but Sylvia probably started in the brand new Glenshaw School, built in 1889. It featured four rooms and was forced to add four more before the decade was out. A large, airy cupola atop held the school bell, and chimneys dotted the four corners. It was a fine building but, alas, did not offer high school in time to serve the Harbaughs. If Alice wanted a high school education, she’d have to go elsewhere. The school cobbled together a two-year high school course in 1900, and possibly Sylvia enrolled, but a year later, she had left Glenshaw for good to go to school. By the end of her public school days in her hometown, however, Sylvia had completed coursework in “physiology, geography, mental, . . . and Barnes’ History. Will complete Franklin’s Complete Arithmetic, Reid & Kellogg’s grammar, algebra and speller, and the greater part of Civil Govt,” and, she added hopefully, “My teacher has offered to help me with Latin.”

Sylvia was, by her own description, “reared in a Christian home. I have always attended Sunday School and church.” She joined the Presbyterian church in Glenshaw in 1899 when she was a teenager, and at various points in her youth joined church groups including the Missionary Society and Christian Endeavor, which she served as president. The Presbyterian church in Glenshaw was a major focus of the community. It started out in an abandoned sickle factory in 1853, and despite such humble origins, it took root. Its handsome new building, featuring a latticework bell tower, was put up in 1887 at a cost of $12,000 ($276,168 today). Sylvia was steeped in a missionary tradition even in unexotic Glenshaw. The year she joined Glenshaw Presbyterian, the Reverend William F. Plummer reported that the church had been involved in mission work for the past twenty years, and in 1899, the congregation raised $441.22 ($10,343 today) for mission projects.

Being a Presbyterian in Glenshaw, Sylvia almost couldn’t help but be bookish. The town featured the oldest public library west of the Allegheny Mountains, its first volume having been checked out in 1888. In fact, the library started at Glenshaw Presbyterian when congregants circulated books after Sunday School. In 1895, the people of Glenshaw held a book party to increase the numbers of books available. They got enough to move the library to a building everyone called “the White Elephant” around 1900. Some books that the Harbaugh children might have checked out included The Boys of ’76, published a century after the American Revolution in honor of that great conflict. They might have leafed through the book next to the model of the Mayflower that was displayed in the library to remind people of the even more distant American past. In 1886 they might have checked out Charles Lamb’s brand new Essays of Elia; and by the 1890s the Harbaughs could check out new acquisitions such as Moths and Butterflies by Julia P. Dallard; Dr. Edward Brooks’ analysis of Homer’s Iliad; and Timothy’s Quest by Kate Douglas Wiggin, who eventually became much better known for Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm. Wiggin invited readers to Timothy’s Quest with the rather lethargic salutation, “A story for anybody, young or old, who cares to read it.” The book suggested that the secret of life was to know your “Mother, Nature, and . . . Father, God” and your “brothers, and sisters, the children of the world.” Wiggin advocated being friendly and obeying the Ten Commandments. No wonder she was popular in the church-based library. However, the story mainly was about the noble, half-humorous attempts of a pre-teen boy named Timmy to find a mother for a motherless baby, knocking on doors and surprising the person who answered with, “Do you need any babies here, if you please?”

Unlike some young ladies her age, Sylvia was “Not very nervous; rather well balanced,” according to a doctor’s examination. She suffered from headaches occasionally, maybe because she was a little nearsighted, but she was very attractive, standing 5'4" and weighing 120 pounds by the time she had grown to young womanhood.

Sylvia aspired to an education, but where would the money come from to pay for it? In fact, where would anyone find a full-blown high school in Glenshaw? Since you couldn’t find any such thing in town, Sylvia turned, as Alice had already done, to Park Academy, the high school branch of Park College in Parkville, Missouri, ten miles north of Kansas City. The Presbyterian school allowed students to work off tuition through a work-study type of program. It also offered the religious bent that Sylvia sought and her family approved. She said she wanted an education “To obtain a christian training so I may be more useful in the master’s work.”

Park Academy was a good arrangement for Sylvia and for the Harbaughs in general; not only were Alice and Sylvia there together, but Beatrice followed them to Park, and Milton graduated from there in 1911. Chambers Harbaugh did not make enough money as a clerk to keep all those children in school, especially in an era when it was not an imperative for girls to go to school. In fact, on Sylvia’s application to the Academy, the form asked, “Can you pay $75 or $60 per annum” ($1,938 or $1,550 today) in tuition, and she answered frankly, “No—I cannot.” Park Academy’s work-study arrangement truly was a godsend, therefore, for a set of forward-thinking parents from Glenshaw who wanted their son—and their daughters—educated.

By the time Sylvia graduated from the high school-level Park Academy, she had wholeheartedly embraced the women’s liberation of her era that encouraged girls to have an education and a job. Of course, girls at Park Academy almost always thought of a college education as a possibility—right there was Park College, offering an appealing, Christly, coed education, and you could go even if you didn’t have a lot of money. That’s what Sylvia planned to do. As she had done in high school, Sylvia would work her way through Park College without her parents having to turn over their entire living to the school. Thus, she did not have to go far to continue seeking usefulness in the Master’s work. One day she would flee the Master’s work on the Titanic, but for now, she grew into adulthood in familiar surroundings.