2

As Far From the Sea as a Person Could Get

Albert arrived at Park Academy in 1904, a good-looking kid with light hair and olive eyes. Slim of build, he was 5'10" and weighed 148 pounds. Stella came with him. Curiously, the Caldwell children entered the high school branch of Park, despite their rigorous high school preparation and their high school diplomas in hand. This probably disappointed both, as they had applied as college freshmen.

The school had been founded thirty years before as “Park College for Training Christian Workers” by George S. Park and Dr. John A. McAfee. The Reverend Elisha B. Sherwood, who had founded the Breckenridge church that William Caldwell now pastored, had had a hand in establishing Park College. While “I found the way clear and organized a Presbyterian church” in Breckenridge, Sherwood said, there was a severe lack of trained preachers fit or willing to lead congregations on the Missouri frontier. He recalled one preacher’s unfortunate experience: “The first Sabbath he preached in a newly organized church. Some roughs came in and undertook to run the town. The citizens objected and the roughs began shooting, which brought on a bad state for the Sabbath day . . . He packed his grip the next morning and left.”

Sherwood had to recruit pastors from New York, and they were often frustrated by the frontier nature of early Missouri. As a result, he said, “I became thoroughly convinced that our only hope of a supply of ministers and Christian workers was to start a college for training them on the field they are to occupy.” In other words, the frontier of the United States needed a lot of spiritual help. George S. Park had offered the Presbyterian church a hotel building to be turned into a school for teaching ministers and Christian workers, but the idea didn’t germinate until Sherwood met McAfee, a Missouri pastor who agreed with Sherwood on the need for a Christian college in Missouri. Sherwood introduced Park to McAfee, and Park College was born.

Mackay Hall, Park College’s signature building, was photographed here by Albert, who kept the photo all his life. The building is still the centerpiece of the Park University campus.

Not only did Park College recruit students from Presbyterian churches all over the nation, but it offered them a bargain education. Dr. McAfee developed a work program that allowed promising young Presbyterians to come to Park at a low cost; in fact, the most promising and most needy could attend without paying a penny. McAfee himself had not been wealthy as a youngster and sympathized with young people of similar background. He conceived of Park College as bringing students into a “well regulated Christian family. The name he gave it was, ‘Park College Family,’” the Reverend Sherwood recalled. You had to be sixteen to join the “Family,” but it was open to anyone who wanted a classical education and “who would honestly and faithfully manifest the disposition to use aright the opportunities afforded and would develop the capacity that promised usefulness in the church and the world.” The Family in the high school arm was to act as a feeder to the college.

The first Family had seventeen students, but by 1893, there were 335. By 1905, the college hosted Presbyterian students from around the world, including locations as exotic as Syria and Bulgaria, alongside more familiar foreign locations such as Germany and Canada. Park graduates often mirrored the international flair of the college by going into missionary work all over the globe. By 1893, the Reverend Sherwood could boast, “Our students are in demand for the home and foreign mission work.”

Albert and Stella could go to school because of the Family system. True, they did have to pay a little, but they got a real deal. Students started in “Family No. 2” or “Family No. 3,” based on financial need. By paying $75 ($1,938 today) to join Family 2, Albert and Stella got to go home at the end of the school term. Students in Family 2 could start out paying just $60 ($1,550 today), but they had to stay into the summer to work, taking a shorter vacation. Albert and Stella had to furnish their own books (which could be rented from the library) and clothing and pillow and blanket. If they did well in school and couldn’t afford to pay further, they moved up to Family No. 1, where textbooks and clothing were free. Family No. 3 was for people who were too poor to enter Family 2; they had a harder workload of half a day, rather than three hours a day for those in Family 2. No matter the work, Albert and Stella—and Sylvia—were well aware that their education was high quality but low price.

Park was pretty far from Sylvia’s home in Glenshaw, but before she finished school her parents moved a little closer, to Colorado Springs, where their house at 321 Bijou Street featured a magnificent view of the mountains. Despite being away from home, Sylvia loved her school experience, throwing herself into various clubs and activities. Stella didn’t like it; by 1906, she was apparently back at home in Breckenridge, paying taxes on her inherited jewelry and figuring out her future. She eventually moved on to Western College in Oxford, Ohio, but dropped out after a year.

Sylvia was undaunted when her dormitory, Park Hall, burned on February 25, 1901. After the flames were doused, Sylvia and the other residents of the Park Hall Family climbed on the ruins to pose for a picture. Among them was Sylvia’s sister Alice, who also lived in the ill-fated dorm. Luckily there was time to save a good deal of the students’ belongings, and Sylvia and Alice and the other girls moved to Barrett Hall. Sylvia was not discouraged by the fire, nor were the Harbaughs in general, as Beatrice and Milton followed Alice and Sylvia to Park. In fact, the presence of Beatrice and Milton caused one of her professors to describe Sylvia as “Careful—Has had the care and general oversight of a younger brother and sister.” Sylvia’s professor also described her as agreeable and energetic —something of a dynamo. Another professor described her as “very charming.”

Sylvia’s dormitory in her high school years at Park Academy, Park Hall, burned in 1901. Here she and other residents climb on the ruins. Sylvia is the girl farthest to the left in the picture, and her older sister Alice is the right-hand girl of the pair in the foreground nearest the camera, behind the bricks.

A year after the dormitory fire, Sylvia had another big scare. She came down with diphtheria in 1902, a potentially deadly disease. Her doctor commented seven years later that she was still suffering from a weak throat related to the diphtheria, but if so, Sylvia bulled her way through it to a college career that included both singing and performing. By the time she left college, in fact, she was known as an excellent “declaimer,” or speaker, and she sang alto in various groups. Clearly, it would take more than diphtheria to keep Sylvia Harbaugh down. Despite the fire and the diphtheria, Sylvia completed her Academy training and qualified to attend Park College.

Both she and Albert continued in the Family work program in college. Albert's tasks included milking the school’s cows. He also worked in a store and in the school's fundraising office, a job he would be a natural at, thanks to his extroverted personality. Albert also kept busy as a janitor in the much-used school chapel. In that job he pumped the organ for church services and various student assemblies. Students went to two Bible studies each weekday. They also read daily from the Bible (covering the entire book in a year), and following good Presbyterian practice, there was no silliness on Sunday. Students went to five Bible studies every Sunday. In fact, there were no classes on Mondays so that students would not be tempted to do homework or secular studying on the Sabbath. Presumably on those Mondays off, Albert cleaned up the chapel after all the Sunday traffic.

The Class of 1909, Park College, posing as freshmen in 1905. Albert is in the upper left corner. Sylvia is diagonally below on the next row, directly below the girl with the white pom-pom dangling from her hat.

Sylvia probably worked in a kitchen or office. If she worked in the kitchen, she may have had to flee on April 24, 1907, when a fire broke out in the one-story dining room that adjoined the Sherwood Home. And then Sherwood Home—her dormitory—itself caught fire. Luckily, no one was hurt, although once again, Sylvia’s residence lay in ashes. Once more there had been time to save most of the students’ possessions. A faulty flue was at fault, causing $7,000 ($170,392 today) in losses (alas, the building was only insured for $3,000 ($73,025 today)). A high wind was gusting that morning, which blew embers onto the college granary. That building burned, too, while students and community members leaped to save barns and outbuildings. Since Albert worked on the college farm, he was perhaps among the worried people battling the flames.

Not again! Sylvia’s second dormitory fire at Park College left her momentarily homeless in 1907. Again, she climbed on the ruins, this time of Sherwood Home. She is in the second row, third from right.

This time Sylvia had to move to the home of a local family, that of G. M. Johnston, who took her in for six months. She made a good impression. “Silvia Harbaugh is a girl we know well and think a great deal of,” Johnston wrote two years later when she graduated. “We regard her as one of the choicest girls in the present senior class of Park College.”

Firefighting aside, Sylvia and Albert each worked at their Family jobs between three and five hours a day around their class schedules. He reported studying three to four hours a night, punctuated by the occasional tennis game. He sprained his ankle once, perhaps playing tennis, and hobbled in to Dr. J. H. Winter to patch it up. Meanwhile, Sylvia put in four or five hours a day studying. Although most professors thought of Sylvia as above average in intellect, one noted that she was not a brilliant scholar. Among other courses, Sylvia and Albert took trigonometry, Greek, Latin, English, and Bible. Sylvia had six years of Greek and got very good at it, tutoring others in the ancient tongue. She had five years of Latin and one of German. Albert likewise had a year of German and a lot of Greek and Latin, although he preferred Latin.

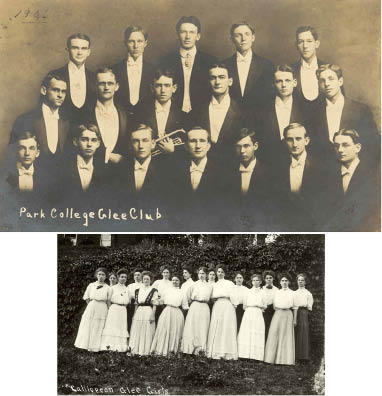

Sylvia and Albert, like all students, were expected to take part in public performances—oratory, singing, drama, concerts. That was easy. Performing was natural to both. Albert joined the College Glee Club, where he sang as the leading second tenor. He was so good that he was chosen as one of the members of the prestigious College Quartet, a gig that took him as a performer across the Midwest. Sylvia was also in two glee clubs and a choir at the college. Both she and Albert were members of the Parchevard-Calliopean literary society, Albert in the all-male Parchevard, and Sylvia in the women’s Calliopean. The clubs socialized as well as sponsored scholarly events. Albert played the double bass in the school orchestra, but not well enough to brag about. Sylvia could pick out tunes on the organ and piano, but she was really good at the mandolin. Sylvia also stood out as a campus actress. One review noted that she always showed “grace and dignity on the stage.”

Both Sylvia and Albert were members of Parkville Presbyterian Church by the time they were seniors in college. Sylvia taught a class of high school-aged boys in Sunday School and had much success turning their thoughts to God and their interest to their future in Christ. However, she was not a holier-than-thou goody-goody. She was popular among the students, according to one of her professors.

Top: The 1906 Park College Glee Club featured Albert, top row, second from right. He was a noted tenor. Bottom: Sylvia, second from right, was a good singer. She sang alto in this group, the Calliopean Glee Club.

One thing Sylvia and Albert did together was to perform in the cast of the Parchevard-Calliopean 1908 production of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale. Albert played the Clown, and in that role he got to deliver some chilling lines about a shipwreck:

I would you did but see how it chafes, how it rages,

how it takes up the shore! but that’s not the

point. O, the most piteous cry of the poor souls!

sometimes to see ’em, and not to see ’em; now the

ship boring the moon with her main-mast, and anon

swallowed with yest and froth, as you’d thrust a

cork into a hogshead. . . .

. . . But to make an

end of the ship, to see how the sea flap-dragoned

it: but, first, how the poor souls roared,

and the sea mocked them . . .

Those would have been mysterious, otherworldly lines to the young man from the Midwest. In Missouri he was about as far from the sea as a person could get. Still, the image of the sea swallowing the ship in a cruel game of “flap-dragon”—and then mocking its victims—was enough to raise shivers. Flap-dragon was a dangerous drinking game in which the player tried to swallow flaming raisins floating in brandy. The image in the lines evoked a nightmarish scene of a ship ablaze, its victims crying heartbreakingly and fruitlessly for help as they were devoured. Albert could not realize how ominously the lines foreshadowed the Titanic.

Sylvia played the role of Hermione, Queen to Leontes. Her character was portrayed as devoted to her husband—albeit falsely accused of infidelity. On stage Hermione made clear, “I do confess I loved him as in honour he required, With such a kind of love as might become a lady like me . . .” Sylvia adored the stage and was a bit of a drama queen in real life, too, according a fellow student who didn’t much like her. And unlike Albert’s lines about the shipwreck, which were just so much poetry that had no real bearing on his Midwestern life, Sylvia’s words of commitment and devotion rang close to her heart.

Although Sylvia’s Hermione was not in love with Albert’s Clown in The Winter’s Tale, Sylvia and Albert were no doubt romancing backstage. By then the two self-confident kids were starry-eyed for each other, and they were seriously discussing making a life together. Graduation loomed, and they had some careful planning to do to get their future in order. They were at the Park College for Training Christian Workers, and it seemed logical that Christian work would be their career choice. In fact, Sylvia had figured for the past five years that she would do missionary work when she finished school. Her cousins, George McCune and Miss Katherine McCune, were already in foreign missionary work. Even Sylvia’s younger sister Beatrice, who somehow had graduated before Sylvia in 1908, was in Honolulu, Hawaii, where she was a teacher at a church-sponsored school. Missionary work was one field where women could take leadership roles, and Sylvia could picture herself doing that.

In the end, their future practically fell into Albert’s lap. The plan to take missionary jobs in Siam began unfolding just after New Year’s of their senior year, a time when almost every senior starts worrying about a job. Still, Albert didn’t think he was shopping for a job overseas. As he described it, “There was a missionary, home on furlough, looking for a young fellow to go out to teach in a Presbyterian boys’ school in Bangkok. The plan was to be there for seven years, learn the language, get on with the running of the school.” The first seven years would be, essentially, an apprenticeship in the principal’s role at the missionary school. After that the apprentice would go home on furlough for a year and then go back and take over the school permanently. The missionary doing the recruiting at Park was Dr. Eugene Dunlap, who spun a good tale as he tried to recruit some of the idealistic young men and women at Park. He reported colorfully that he and his wife had traveled around Siam on steamers, elephants, buffalo carts, and canoes.

To Albert’s surprise, Park College President Lowell M. McAfee advised that he should consider the job that Dunlap was pitching. Albert was flattered. He spoke to Dr. Dunlap for an hour and a half about the position in Bangkok and then started up a correspondence with him. “I have intended to make teaching my life work, but had not thought seriously of the work in the Foreign field, before my conversation with Dr. Dunlap,” Albert confessed later to the Presbyterian Foreign Missions Board. Albert consulted with his parents, who agreed with some reluctance that he could go. He also talked to church elders and to another foreign missionary about the job. And of course he conferred with Sylvia, who had been hoping to follow her cousins into missionary work anyway, and whose parents consented to her desire to join Albert in teaching overseas. Perhaps her career goals influenced Albert; women’s career choices were somewhat limited, after all. As one newspaper put it after the Titanic wreck, “He did not believe he ought to take his bride to such a country,” but Sylvia had set him straight: “ . . . she said she could and would go if he did.” Albert decided he wanted the job. There was a lot of appeal in following in the footsteps of his father in doing God’s work, albeit in the role of a missionary teacher and not as a pastor. And Sylvia would be there alongside him.

In fact, Sylvia already had a connection to Siam. The well-known Bangkok missionary Edna Cole had come to campus with “a young lady from Siam,” as Sylvia described her, in 1904. Truthfully, the young lady, Beatrice Moller, was an English-speaking girl who helped Miss Cole at the girls’ Wang Lang School in Bangkok. However, Sylvia thought Beatrice needed help fitting into the American scene. As Sylvia put it, “I have been closely associated with her in helping her understand our American ways.” Apparently Beatrice reciprocated. Sylvia rather naively felt better prepared for mission work in Siam as a result.

Albert, who had described himself as a somewhat nervous person but who had been described by someone else as having a personality that was “commanding, rather,” was, indeed, both nervous and rather commanding as he planned for his career. He and Sylvia would graduate on June 24, 1909, and he let Presbyterian officials know he didn’t expect a single day to go by before he started a job. He and his intended could sail for Bangkok the day after graduation, he insisted, forgetting that perhaps it might be nice to get married before they left. The job, he had heard, paid $625 per year ($15,214 today) for a single man, plus residence and transportation. If he were married, his salary would be a generous $1,250 (now $30,428) plus residence and transportation. When you counted in the house and transportation, it was more than twice what the average Presbyterian pastor made in the United States. Albert hoped his salary would include transportation for Sylvia as well. He anxiously asked for confirmation that her trip to Siam and back would be included in the pay. He told a key official that it was critical that his fiancee go with him, saying, “I thought at first of going alone but the girl whom I have for a long time intended to marry, expressed her willingness to go. I am sure I can do better work by having her with me.” He added as a prophetic afterthought, “Of course we do not expect the missionary life to be an easy one.”

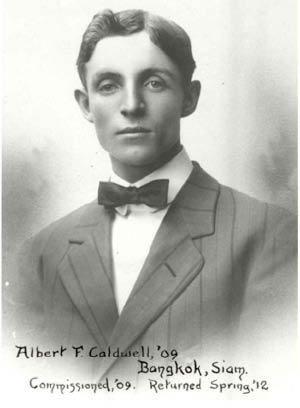

A handsome fellow: Albert’s college senior picture of 1909, with information about his missionary service added later.

Albert expected an immediate reaction to his application from the Foreign Missions Board. Instead, he played a fidgety waiting game. He groused to Stanley White of the Board, “I am turning down good positions, every few days now, so am anxious to hear, what the result of the Action of the Board will be.”

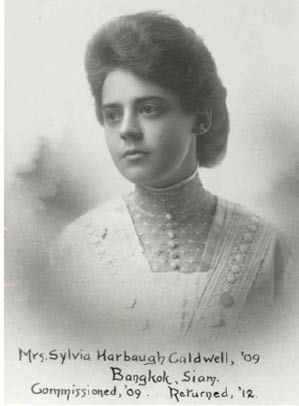

One of the prettiest girls from Colorado (as a newspaper called her after the Titanic): Sylvia’s 1909 college senior picture, with information about her missionary service added later.

White was alarmed to hear about the jobs Albert turned down. He warned, “I would also say that the position you have in mind, at the Christian Boys High School is one that needs not only head knowledge but experience in teaching and managing a school.” Albert had the former but not the latter, and White was hinting pointedly that Albert should look elsewhere.

Dr. McAfee did his best to quell any worries the Foreign Missions Board had about Albert’s lack of teaching experience. McAfee recommended Albert for the job with ringing words: “We have found him a fine student, a man of refinement, a leader among his fellows, bright and cheery in his work . . . He has not taught before but I think him possessed of those latent qualities that will develop in a satisfactory manner . . . the Board makes no mistake if he be accepted for the position.”

Albert’s anxiety over the job only increased. He noted crossly to White, “As it is now, I go to the Post Office every mail with the hopes of hearing your final decision . . . I know I am very impatient and if only myself were concerned I would not care so much.” The exasperated White replied, “I would call your attention to the fact that it is barely a month since your application . . . and that it is a very hazardous thing to be over-precipitate in determining a man’s life work.” White advised him to interview again with Dr. Dunlap, which Albert did.

White reported a positive reaction from Dunlap on May 20, 1909, and not only told Albert and Sylvia the good news, but insisted they come to New York to a conference for outgoing missionaries. The conference would take place in June, with the Presbyterian church paying their expenses to New York, including transportation and entertainment. Albert and Sylvia could take the train round trip from Kansas City for $40 ($974 today), a dazzling sum for students who couldn’t afford regular college tuition. The ticket price showed the future missionaries how key it was for the Board of Foreign Missions to pay their travel to and from assignments around the world. They would ultimately be haunted by the Board’s stranglehold on travel funding, but of course they had no inkling of that yet.

Despite the church having paid such a pretty penny for tickets, Sylvia and Albert’s train was delayed and they missed a connection. They had to send a telegram from Detroit, explaining their late arrival.

One goal of theirs in New York was to purchase an “outfit” for Siam—the household goods and specialty clothing they would need. The Presbyterians allotted $400 ($9,737 in today’s dollars) for such. Albert worried whether that amount would be sufficient, and he was assured that the church did not intend to send them into the field unprepared. A missionary to Melanesia, not all that far from Siam, suggested that missionary schoolteachers take table, chairs, bed, a deck chair, blankets, sheets (you’d only need a sheet to sleep under, he assured), a heavy covering in case of fever, a tub and soap for washing, irons, canteens, dinnerware, can opener, corkscrew, cookware, stove, lamps or candles, cool underwear (no flannel), a belt that would protect the stomach (to ward off disease), raincoat, lots of boots (they wore out quickly), straw hats, spats for ladies (to protect their ankles from mosquitoes), and the all-critical mosquito net, which meant you needed to bring needles and thread to repair the net immediately as needed. Shorts and short sleeves were okay, too. Presumably while Albert and Sylvia were in New York, they purchased and arranged for shipping their outfit to Siam, as Dr. Dunlap had suggested, because goods and freight were cheaper from New York. Sylvia perhaps dropped down to Washington, D.C., on this trip, on a specialized missionary task of her own: she would represent Washington-area Presbyterian churches in their fundraising for the Jane Hays Memorial Fund, which aimed to build a new girls’ school in Bangkok.

Even after the big trip to New York, there were still hitches. Here Albert was with a job in hand, when it was almost snatched from his grasp. Dr. McAfee happened to run into White and mentioned Albert’s name. White’s reply caused a crisis, and he got a chewing out from Albert, who wrote to him, “President McAfee gave me quite a scare . . . He said that he had been in your office and you had informed him that another man named Conybeare had applied for the same position” and that Conybeare would likely get it. McAfee apparently turned in a panic to Dunlap, who assured him that Conybeare was applying for another job, “the Y.M.C.A. work.” Well, that was a relief, but Albert wrote to White, just to be sure.

The Bangkok job was sure, and he and Sylvia were formally appointed on June 7, 1909. As the icing on the cake, the newly minted missionaries had a companion heading to Siam. A Park College classmate, Ed Spilman, was going over to Bangkok, too, to work for the American Presbyterian Press.

What Albert and Sylvia didn’t know, as they prepared for their life together in Siam, was that Professor M. C. Findlay of Park College had done his best to discourage the Board of Foreign Missions from taking Sylvia. His comments reflected an interesting mix of admiration for Sylvia and disdain for the missionary scene, which was out of control, as he saw it. A Park graduate, Victoria McArthur, had nearly worked herself to death in India, and she was now home for some badly needed rest and relaxation. Findlay did not like what he saw of poor Victoria, and he hoped fervently as a result that Sylvia would not go abroad. He wrote on Sylvia’s recommendation form:

I do not believe Miss Harbaugh is well fitted for a frontier life and some of the physical hardships required of some missionaries. I do not believe her health although good for the average young woman, will stand what Miss Victoria McArthur and others like her have gone through. I am getting more and more of the opinion that some of the work expected of the missionaries is impossible. Some of the missionaries long in the field have become so pigheaded and bossy that it is almost impossible for the new missionary . . . to work with them and maintain their self respect. Miss Harbaugh is able, agreeable and cultured and I should hate to see her sent to some fields, which might be mentioned. In the right place she will do well.

The fact that Findlay was a biology professor may have given his assessment of Sylvia’s stamina and health even more credibility.

Another reference for Sylvia hinted at a little doubt as to her readiness for the religious part of mission life. G. M. Johnston commented, “The active vital Christian Character which comes with the experience of deepest need and the abundant supply of God’s Grace—she has not yet received.” However, he heartily recommended her, expecting her to progress quickly. He added, “I think there will be no mistake in her appointment.”

Sylvia and Albert were blissfully unaware of these foreboding assessments of Sylvia. They only knew they were due to leave for Siam in September.

But first there were the matters of graduating and getting married, which almost seemed anticlimactic against the bright horizon of the future. They graduated with A.B. degrees on June 24 —Albert graduated with honors and gave an honors oration at graduation. They spent the time between their graduation and the end of August planning their wedding a little and their move to Siam a lot. The wedding was held at Chambers and Sylvia Harbaugh’s home in Colorado Springs on September 1, 1909, with the beautiful mountains looming just over the brow of the hill of Bijou Street. Albert’s father came over from Missouri to officiate; he was now the pastor at the Presbyterian church in Marceline. Thirty-five witnesses were on hand.

The newlyweds set out for Siam the very day of their wedding. Although it seemed like an idyllic start to an equal partnership, it could not have been a good way to start a marriage. No doubt the journey to their ship, leaving from San Francisco, counted as a honeymoon, but after a mere week as a married couple, they found themselves aboard the Manchuria, set to sail the Pacific. Albert celebrated his twenty-fourth birthday on the day they left America for Siam, making their farewell to the United States all the more significant. Somewhere back in the Midwest, Stella turned twenty-three and was in love herself and would shortly marry. She had come back to Missouri from Ohio and was now planning to wed J. E. Plummer, a former bookkeeper at the local bank who had recently become a “frank-spoken, genial” lawyer. A piece of childhood died that September 8 for the twinlike duo. Married life lay ahead. For Albert and Sylvia, marriage brought them to a sheer cliff of change. According to their career plans, they’d never really live in America again.

The Manchuria tried hard to be a luxury ship, bragging in its brochure that it was the steadiest boat on the Pacific. Its construction, the ad went, “assures freedom from seasickness.” Alas, the advertisement was wishful thinking. During the long, long crossing of nearly six weeks, Sylvia was seasick. Landlubbers from the Midwest, she and Albert were not used to boats or the sea, as they found out most unpleasantly.

If it hadn’t been for the uncomfortable nature of the voyage, the trip would have been a true excitement to young people from poor backgrounds who wanted to see—and save—the world. “We went out by way of the Hawaiian Islands, Japan, and China, and round past what is now Vietnam and up the Gulf of Siam, and 20 miles up the river to Bangkok,” Albert recalled more than sixty years later, the trip still as clear in his memory as though he had just taken it. On the way they saw cities they could not have imagined as they milked cows and cleaned kitchens at Park: Honolulu, Hawaii (perhaps they managed a visit with Beatrice, who told everyone the place was a paradise ); Yokohama, Kobe, and Nagasaki in a rapidly modernizing Japan; the Chinese trading city of Shanghai; and the British outpost of Hong Kong. They finally arrived in Bangkok, Siam, on October 16, many weeks and a world away from where they had begun. It had been an interesting trip, and Asia was already fascinating. But most of all, Sylvia was relieved to make solid land again.