Dungeons & Dragons

The following Monday morning, Dad escorted me to the shoot. I could tell how happy he was about my role because he flagged a cab instead of us walking up to Amsterdam to catch the northbound bus.

Dad said almost nothing while we rode. When he did break the silence, he spoke only to the driver: “Take Eighty-Sixth across, please.” When I asked him if we could go by our old apartment, even though it would be farther uptown and cost more, he said, “Actually, driver, take Ninety-Sixth.” My desire was only partly nostalgic. While we waited for the light to change on Broadway, I scanned all four corners of the intersection for Amanda. I had an overwhelming urge to tell my father about meeting her but wasn’t sure how to begin. Mostly I wanted his advice about how many days I should wait to call her. Dad had rolled down his window. His curly hair was damp and drying in the breeze.

“Are you rehearsing today?” I asked, because he was particularly well dressed.

He nodded. “There’s a run-through this Friday at the St. James,” he said. “I’m hoping you’ll all come see.”

With so little traffic, we raced down the street at highway speed. We passed Boyd Prep on our right, and I smiled at the thought of missing school, at this jailbreak freedom, and Dad, noticing where we were as well, turned to me and mirrored my expression, and it felt like it was our city, the one its nine-to-fivers rarely got to see, the one we, not caged by such hours, sped through, unimpeded, and enjoyed. I thought about Oren’s advice, and it occurred to me that, were I to become famous, I’d never have to go to school again. Was that something I wanted? The park’s smells as we entered the transverse were pungent and fresh. The birdsong was still audible when we stopped at the Fifth Avenue light.

“I met this girl,” I said. “She gave me her number.”

But Dad had become preoccupied. We were headed down Fifth, and the moment we turned east onto Ninety-Second Street, he said to the cabbie, “It’s the movie set up there on the left.” And I forgave him this bit of showing off because I was desperate for his answer.

“But I didn’t want to call right away,” I said.

“Wait two or three days,” he said as he paid, hurriedly, and checked his watch. “That way you don’t seem overanxious.”

The gofer greeted us at the police barrier. When Dad tried to enter with me, he said, “I’m sorry, Mr. Hornbeam doesn’t allow guests on set.”

Dad’s eye twitched. “But I’m his father.”

“It’s a strict policy.”

Dad glanced at me, as if for help, then said to the gofer, “I’m an actor as well.”

“You could be President Reagan and it wouldn’t make a difference.”

Dad blinked several times. I could tell he was disappointed. He’d skipped the Y this morning and shaved at home. He was wearing a nice shirt, slacks, and his tan Paul Stuart coat. And it dawned on me that he’d dressed for Hornbeam, he’d assumed he was going to meet him, and that the introduction might be consequential. That he’d considered this an audition of sorts.

“All right, son,” he said, perhaps a bit loudly, maybe a smidge pissed, “have a good day at work.” He pulled me toward him by the shoulder, kissed my forehead, and watched me leave. But when from the top of the town house’s steps I turned to wave goodbye, he was talking to a pretty lady carrying a toy poodle. She pointed at me and he nodded—“My son,” he said—then scratched the dog’s ears.

After makeup, I positioned myself before the same living room window to watch the Nightingale entrance for a sign of Amanda. I eyed the girls strolling up the block, most with friends and a few of the younger ones holding their parents’ hands as they were dropped off at school, but did not see her. Soon the street was empty of students, the blue doors had closed, and, disappointed, I settled in to work. Which meant a lot of waiting for setup, and for Diane Lane, who played my math tutor, to get done with makeup as well. Jill Clayburgh and I chatted. She too had just come out of makeup and stood with the odd stiffness of being fully in costume. She told me she admired how relaxed I seemed, given how challenging it was to arrive on set like this, midstream, as it were, no table reads to go by, no preproduction direction from Hornbeam, and that I should feel free to ask her any questions.

Diane Lane, who’d just joined us, said the same. When Clayburgh asked me what I thought of our characters’ relationship, I, entirely unprepared to answer—I still hadn’t bothered to finish the script—told her I was going to ask her the very same thing. She said she thought I was understandably protective of my mother, a dynamic reinforced by the fact that I was more like a father to my father, since he was as impulsive as a child and his absence in my life had made me the man of the house. Which, when you thought about it, Clayburgh continued, also made me the surrogate husband to my mother. “In short,” she said, and bumped her elbow to mine, “you’re a psychoanalyst’s dream.”

The living room where we were shooting had been transformed, swapped out with new furniture. When I asked Lane why everything was different, she said, “Last week they finished all the scenes that take place on Konig’s movie set. Now we’re shooting the ones that take place in his actual town house. They even swapped out the chandelier.” She winked. “Don’t worry, I won’t tell Mr. Hornbeam you haven’t done your homework.” Then she put a finer point on it. “Not that I’ll have to.”

Several run-throughs later and we were ready to shoot. In the scene, Lane and I have just finished our tutoring session. I am walking her out, through the living room, and when she stops to briefly check in with Clayburgh, Konig, introduced to her for the first time, can’t help but make chitchat. His interest is obvious; he is gobsmacked by her beauty; he is like a father talking too long to a gorgeous babysitter he’s already paid for the night. In the midst of our third take, Hornbeam broke character and said, “Cut, please.” He pulled me aside.

“When Diane and I are talking,” he said, “I want everything here”—he aimed two fingers at his eyes—“like a tennis match: Diane, me, Diane, me. Until we’re finished. And then give a quick glance at your mother. To gauge her reaction. And then react to that.” He added, “You were with us on the last take, but then Jill read her line and your attention went kablooey. Are we clear?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Just maestro will do,” he said.

Hornbeam, amid all of this—between directing and acting and everything else going on—had noticed exactly where I was and where I wasn’t.

Lane raised an eyebrow as if to say, Told you.

That afternoon, when Nightingale dismissal paused the shoot, I looked up from my script and scanned the auditorium’s terrace for Amanda, and each time the blue doors opened, I watched hoping she would be the next one through. It had been three days since we’d met, and based on Dad’s advice, I decided to phone her that evening. And later, when I took the same bus home that we’d ridden crosstown, I gave our first encounter an imaginary do-over, mustering my courage and taking the seat next to her, where I sat now, in reality, in order that we might chat during the entire ride. And being in the mood for pretend, having not bothered to get my makeup removed, in the hope that I’d run into her again, and noticing several straphangers notice my too-vivid features on my already too-large head—an oversight, it was not lost on me, that was not only meant to call attention to myself but was straight out of Dad’s playbook—I took another imaginative mulligan and, in this version, did the even bolder thing: I hopped aboard the northbound Broadway bus with Amanda, saying something clever as we took our seats and began our journey uptown, something Hornbeam would say, or Konig, a line straight out of a movie, like “Take two.”

I made the call to Amanda that night from my closet study, since it was here that I had the most privacy. I took a break from reading through the script and, finally mustering my courage, dialed Amanda’s number. But the line was busy. I tried again a few minutes later. Same. I passed the time looking at Dad’s photographs, which he stored in boxes stacked beneath my floating desk. There were hundreds of eight-by-ten and five-by-seven prints, along with contact sheets from when he was in the navy. There was a smaller box that contained pictures from my parents’ honeymoon: of Anthony Quinn, his arms draped over my mother’s shoulders; on the deck of the SS Cristoforo Colombo, which they’d sailed to Europe. Of Mom on a chaise longue on the ship’s deck, bundled in a coat and blanket and reading. Of Mom, beaming, as she stood beneath the Eiffel Tower. It was not lost on me that their happiness of late—that is, since Dad had secured this role—most closely resembled these photographs from their earliest years. And smitten as I was, I too believed I understood the desire to sail off into the future with someone. I would tuck in Amanda’s topside blanket so that she was comfortably cocooned and later we’d dance the night away after loads of champagne. Except I would leave the movie star stateside. Unless I was the movie star. Which, it occurred to me, was entirely possible and would not, when I thought about it, be the worst thing that could happen to me.

I dialed Amanda’s number again and this time it rang, just as my father opened the door to the closet and gave me a slip of paper. While You Were Out, it read.

“This woman left a message for you,” he said, and handed me the note. For: Griffin, it read. Urgent. Mrs. Metcalf. Please call. I didn’t recognize the name or number.

I cupped the speaker. “I’m on the phone.”

“She said it was important.”

I held up the movie script, which had warding-off powers over Dad like a cross does a vampire. “I’m busy,” I said.

He winced an apology and softly pulled the door closed.

I crumpled up the note and threw it away.

Then a woman answered.

When I asked to speak to Amanda, she said, “Wer ist das?”

When I told her I didn’t understand, she said, “Qui est-ce?”

When I asked if this was the West residence, she replied, “West-san no otaku deshouka?”

When I apologized for having the wrong number, she said, “Listen, kid, Amanda’s babysitting. She’ll be home around seven.”

Then she hung up.

When I called back at the appointed time, Amanda answered. “Oh,” she said when I asked, and lowered her voice. “That was my mom.”

“She speaks a lot of languages,” I said.

“She mostly just knows phrases. But her accents are good.”

“My dad’s good at accents too,” I said. “Or I guess dialects.”

“What’s the difference?” Amanda asked.

“He says it’s how you pronounce things.”

“I think that’s accents. Dialects have to do with the region.”

Someone on my line picked up and began dialing. Long notes on the touch tone, as if they were playing an organ.

“I’m on the phone!” I said.

“I need to call Matt for my homework,” Oren said.

“I’m talking right now.”

“Well, make it snappy,” he said, and hung up with a clatter.

Amanda said, “Who was that?”

“My brother.”

“Is he younger or older?”

“Younger,” I said. This was followed by the sound of our breathing on the line. “Do you have any brothers or sisters?”

“A brother,” Amanda said. “He’s older, but he mostly lives with my father.”

Dad picked up and started dialing.

“Hello?” I said.

From his bedroom, Dad shouted, “Oren, hang up the phone!”

Oren yelled, “Griffin’s on the phone!” but I could also hear him clearly through Dad’s receiver.

Mom said, “Would you two please stop screaming at each other?”

Dad said, “Griffin, I need to call my service.” Then he hung up.

There was another long silence.

“Your father?” she said.

“Yes.”

“He has a nice voice.”

“It’s a bass baritone,” I offered.

Not unkindly, Amanda said, “Do you want to call me back and start over?”

“No,” I said, “but thanks.”

“De nada,” she said.

“Good accent,” I said.

“Good answer,” Amanda said.

“Do you take Spanish?” I asked.

“French.”

“Can you speak it?”

“Un petit peu,” she said. “You?”

“Un poco,” I said.

“Are you going to do the play?” Amanda asked.

“I can’t.”

“Why?”

“You know the movie they’re doing across the street from your school?”

“Yes.”

“I’m in it.”

“Really?” she said. “Like a part?”

“Do you want to see us film on Friday?”

“Absolutely,” she said.

“We’re shooting outside so just come by when you get out.”

Someone spoke to Amanda in the background. “My mom needs me to run an errand now, but I’ll see you at the end of the week.”

After she hung up, I replaced the receiver in its cradle. Then I pulled the chain to the bulb in the ceiling. In the dark, I slid down in my chair, resting my feet against the door. I laced my fingers behind my head and rocked onto the chair’s back legs. I could feel the entire outline of my body, toes to fingers, soles to shoulders. The exact width of my smile.

By now, everyone in my family had read the script of Take Two. On its facing pages, in her perfect cursive, Mom had taken notes that read Motif of performance, Movie within the movie, Triangles, or Motif of adult injury. Oren had put hearts on the call sheet when Diane Lane was shooting. Two years ago, after seeing A Little Romance, he had taped her cover photo from Time magazine—its headline read “Hollywood’s Whiz Kids”—to the wall by his bed. Dad, who’d been rehearsing late, so that he often missed dinner, had highlighted the lines in all my scenes.

The plot of Take Two was hard for me to follow because it was out of sequence. It cut between Konig’s past and present, between the movie that he was making as well as what was happening in his life, which was a mess because the people he’d hurt or ignored while making movies—his ex-wife, his son, his sister, and his fiancée—were all making demands on him for different reasons. His older sister, Blair (played by Cloris Leachman), who was dying of cancer, had been estranged from Konig for years because she felt that the sisters in his movies were, she said, “gross misrepresentations” of her. She wanted Konig to admit to this and apologize before she died. “I never browbeat you like Claudia in Hershkowitz,” she said from her hospital bed, “and I certainly didn’t tell your wife about your affair, like Mira in Mishegoss!” At the same time, Konig’s ex-wife and my mom wanted to clear the air between them. Not only because she was sad and angry that their marriage had ended, but because she felt his impending marriage was a distraction from all the problems between him and me, which she believed he was running out of time to repair. “Just like you’re running out of time to patch things up with your sister,” she told Konig during a fight at the Russian Tea Room. Meanwhile, Shelley Duvall, playing Konig’s fiancée and the star of his new movie, was having terrible panic attacks on set because she was certain he was disappointed in her performance. Plus, she was paranoid that he was obsessed with my math tutor—which was true—whom I had a crush on as well. All these factors were interfering with the completion of Konig’s new film, “not least of which,” he complained to his psychologist, played by Elliott Gould, “is that I keep rewriting the final act.”

On set the following day, while we were mid-scene, Hornbeam called, “Cut.” I could tell he was slightly annoyed. Once again, he pulled me aside. “Griffin,” he said, “I need you to remember what’s going on here please. Earlier that morning, you had your Saturday session with Dr. Gould. So the talk you two had about your father is very much on your mind.” I recalled the scene to which he was referring but didn’t quite have it at hand, which Hornbeam must’ve sensed, because he added, “Take the pile of manure you dumped about your father in therapy and hand it off to me first chance you get.” We did at least ten takes. When Hornbeam finally said, “Print that,” he was not emphatic.

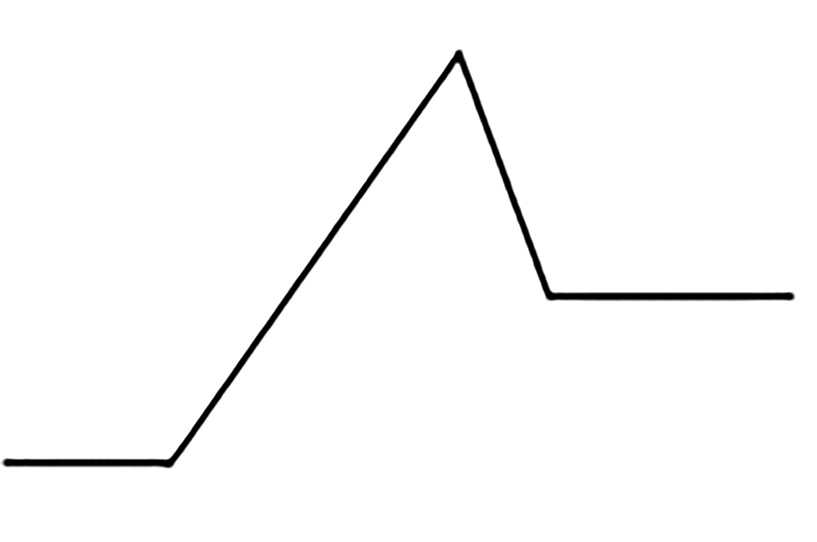

And when we wrapped for the day, Hornbeam called me over to join him by the window seat. There was a view from here of Nightingale’s blue doors, which I made every effort not to look at, girding myself, as I was, to be dressed down. To my surprise, Hornbeam held up a sheet of paper and from behind his ear produced a Sharpie. He laid the former between us. “You know what Freytag’s Pyramid is?” he asked. When I shook my head, he said, “It describes the shape of most stories. I find making one of these always helps me to know where I am when I’m acting in one of my pictures. Kind of like a map. Especially when we’re shooting scenes out of order.” On the blank page, he drew a flat line that rose to a summit, dipped, and then, halfway down, extended straight out from its midpoint:

“See this flat line here? That’s the exposition. The ‘once upon a time there was’ part. You take Latin? We begin in medias res, in the middle of a thing. Like in dreams. Next, we’ve got our inciting incident. Here. At the pyramid’s base. That’s the event that spins everything in a different direction. I like to call this the ‘interruption of quiescence’ but only because it makes me sound smart. ‘Quiescence’? It means ‘quiet.’ You see The Empire Strikes Back? Of course you did. Even the Ayatollah saw it. At a private screening with Brezhnev. According to my sources, they thought it was better than the first one. Anyway, you know when Luke escapes the snow monster and Obi-Wan Kenobi tells him he’s got to go to the Dagobah system and train under Yoda? Inciting incident. If we’re splitting hairs, it’s when they destroy the rebel base, but you get my drift. And everything intensifies from there, this rising action going up, up, up, the pyramid like a pot of water coming to a boil, there are all sorts of fights and chases, our heroes face all kinds of obstacles all way to here”—he pointed to the summit—“the climax. The point of maximum tension: the battle between Vader and Luke. No quarter asked and none given, the fight ending when Darth chops off Skywalker’s hand. ‘Luke,’ Vader says, ‘I am your father.’ After which there’s the denouement, which is French for basically phew, which is falling action, is aftermath and mop-up. Luke escapes, gets his robot hand. He’s permanently scarred, he is forever partly his father. The rebels live to fight another day.

“Now, me, before I start a picture, I make notes on this pyramid, all along these lines, about the important things that happen in the story. Here”—he made a dot on the base of the pyramid—“is where Konig reads the terrible reviews of his latest picture.” Another dot. “Here: where Blair learns she’s got three months to live.” Another dot. “Here: the scene where Elliott and Bernie have their breakthrough therapy session and afterward Bernie confronts Konig about being a shitty father. And here: where Konig figures out the end of his movie. This sheet, I label P, for ‘plot.’ ” He made a P in the upper left-hand corner, then laid another sheet of paper over it and traced the exact same lines. “This sheet, you label B, for ‘Bernie.’ So…” And he made dots along the graph. “Here’s where Bernie’s dad meets Diane. Here’s where Bernie and his father have a catch in Central Park. Here’s where Bernie finally lets his father have it for being so out to lunch his whole life.” Then Hornbeam laid the B over the P. Then the P over the B. I could see the tracery beneath each. “This way,” he said, “you can chart your character’s movement, from alpha to omega. Because that’s what every story’s about, young Skywalker, it’s about moving off a starting point or resisting change with everything you got. Protagonist versus antagonist until death do they part. Use this method”—he held the sheets and Sharpie toward me—“and you always know where you are when we’re shooting.” He retracted them when I reached out. “But it doesn’t work,” he warned, “if you don’t make your own. Comprendo?”

I spent the entirety of Tuesday night doing this, to the exclusion of my school assignments. On Wednesday, after a particularly long day of shooting, and only three takes to nail my therapy scene with Elliott—we used the third-floor study as his office—Hornbeam placed both his hands on my shoulders and said, “Would that every adult I worked with took direction so well.” And this filled me with pride.

But that night, I found myself so far behind in my homework, I was miserable. I had school the next day, plus a big scene to prepare for Friday’s shoot, and especially with Amanda coming, I wanted to be at my best. It felt like The Nuclear Family all over again, plus Dad was home early.

Before dinner, Mom knocked on my door and then opened it. “I’m making pork chops,” she said. “You and your dad’s favorite.” She surveyed the scene. “You want some tea or something?”

“I’m fine.”

She cupped her hand to her mouth and whispered, “It would mean a lot to your father if you rehearsed with him.”

My glare did not mean no, so she smiled like we’d made an agreement and went back to cooking.

If I’d had a stopwatch, I could’ve set it to the exact time it took Dad to knock.

“Mom said you wanted my help.”

I opened the door and glumly handed him the script. He visibly brightened, and I followed after him as he took a seat on the couch. I sat across from him, on the rocking chair, and rocked as if I were generating electricity.

“Maybe you want to stand,” he said.

“Why?”

“To work on appearing relaxed.”

“Can we start?”

“Suit yourself,” he said.

We ran through the scene once. A few lines through the second, Dad said, “Maybe a little more oomph on that one. With a dramatic pause first.”

“Where?”

“ ‘The girl I like,’ ” he said, “ ‘she…she doesn’t know I exist.’ ”

“There’s no ‘she’ in the line,” I said. “It’s: ‘The girl I like doesn’t know I exist.’ ”

“Ad-lib it,” Dad said. “For effect.”

“Hornbeam hates that.”

“You’ll never know till you try.”

“Jill Clayburgh tried today. Hornbeam told her to read the line as written. And I’m no Jill Clayburgh.”

“Fair enough,” Dad said, but he was crestfallen.

We proceeded.

“The girl I like doesn’t know I exist,” I said.

Dad held out his hand, which he bunched into a fist. “Exist,” he intoned.

“You sound like a depressed giant,” I said.

“Fine,” he said, and threw down the script. He stood. “What could I possibly know”—he gestured toward our third-story view of Manhattan—“about acting?” Upon which he thumped out of the room.

Dad was still grumpy when we sat down to eat. I was explaining Freytag’s Pyramid to Oren when Dad asked, offhandedly, “How does the movie end, by the way?”

Mom snapped, “I thought you said you read it.” She was pissed off at him for reasons unknown, but which had transpired sometime between our rehearsal and dinner.

“I read enough to get the gist,” Dad said to her.

“Maybe if you finished,” Mom said, “you could talk to your son about character motivation. Like satyriasis.”

“What’s that?” I said.

Mom glared at Dad as he hunched over his plate, biting the last bits of pork from the rib.

“I read it,” Oren said. “I thought it was talky. Like our family, but on amphetamines.”

“Since when do you know anything about amphetamines?” Mom said.

“Okay, then,” Oren said, “cocaine.”

“I thought it was brilliant,” Mom said to him. “I think it’s a dead-on description of the price an artist pays for his narcissism. Look up that word,” she went on, turning to me, “if you don’t know what it means. And I also thought”—here she glared at Dad—“the tragedy of Konig’s character is that he needs certain things from certain people at certain times. And when his needs change, he discards them like old toys. As for your opinion,” she said to Oren, “keep your half-baked ideas to yourself.”

There was suddenly a terrible crack.

“Fuck,” Dad said, and cupped his mouth. “Fuck!”

He hurried to the bathroom. Mom slowly shook her head as she watched him go.

“You busted a crown, didn’t you?” she called after him. Then she raised an eyebrow at us in sick glee. “Knick-knack paddywhack,” she said, “give a dog a bone.”

On Thursday, I was back in school and hurrying to the library, when I spotted Mr. Fistly walking toward me. He was strolling, deliberately, down the hallway toward his office, reading a sheet of paper, but just as we passed each other he paused without looking up and, having seen me through the eyeball in his ear, said, “Mr. Hurt, join me in private, please.” From her desk, Miss Abbasi glanced at me as I passed. She let me register her disappointment and then returned to her typewriter’s keys. I had no idea what I’d done wrong and checked off the list: I’d turned in my excuse to Mr. McQuarrie for missing school all week; miraculously, my assignments were in on time; my grades had improved since wrestling season had ended; I was wearing loafers; I even checked my zipper. Mr. Fistly took his seat, placed his elbows on his desk, pressed his fingertips together so they formed a steeple, and began to speak.

“I have just received a rather disturbing call from Mrs. Metcalf. Does that name ring a bell?”

“No, sir, it does not.”

“Exactly,” he said. “You are unaware of her identity because you have set eyes on her once. At the Nightingale-Bamford School. After not only auditioning for her play but apparently accepting a lead role in it. Upon which you did her the discourtesy of neither returning her calls nor attending rehearsal this week, inconveniencing her terrifically while embarrassing me as well, since she is a respected colleague. I would have you inform her yourself that you did not intend to participate in her production and apologize, but I think so little of your character I find that sort of object lesson would be lost on you. Not to mention that I trust your follow-through even less. So please reserve this Saturday for detention. I did not excuse you, Mr. Hurt.”

I turned around at the doorway to face him.

“Make a point of seeing Mr. Damiano before this afternoon is out. In fact”—Fistly shot a cuff and checked his watch—“he is at the moment in his downstairs office. He will inform you as to how we are going to proceed with the matter.”

The office to which Fistly referred was the basement theater. It was below Boyd’s modern wing. The flight down was like descending through an aquifer, since Boyd’s swimming pool was also located here. With each step the stairwell turned warmer and more humid, the smell of chlorine grew more powerful, and the metal handrail became slicker with condensation. The basement theater was to the left, at the end of a long hallway, past Boyd’s school store and the cavernous book storage room next to it, presided over by Mr. McQuarrie. He sat at his desk now—the space’s only light a small lamp—licking his finger to flip through a stack of pink receipts, like a monk over an illuminated manuscript. When he caught my eye, he flashed a naughty smile—“G’day, Mr. Hurt”—and I hurried past, suppressing a shiver.

The theater was a low-ceilinged room, long and rectangular, black-walled and dimly lit but for the tiny square of stage at its far end. Mr. Damiano, who presided here, taught honors English and drama. He was bearded and bearish in build, and his facial hair, grown to his cheekbones, hid what I’d once noticed were terrible acne scars. He was a teacher who did not have students so much as acolytes and was a fan, in all months of the year, of patterned scarves knotted at their ends. In short, he reminded me of the worst of my father’s students—lovers of costume but actors in name only. He stood by the entrance, leaning against the lighting booth, and briefly acknowledged me as I entered. He was smoking a cigarette contemplatively. Everything Damiano did—but especially now, aware, as he was, of me watching him watch Robert Lord and Kingsley Saladin, his two favorite seniors, rehearse a scene—was adverbial. He beheld them lovingly, devotedly, considerately, obviously. Italics his. I took a seat on a foldout chair and it squeaked. Damiano raised a finger to his lips and nodded toward the pair of students. Lord launched into a monologue, and Damiano, sensing my eyes on him, began to mouth the words in tandem, as if he were so stirred by the language he had to simultaneously perform it himself. “All the world’s a stage,” he and Lord began:

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms;

And then the whining school-boy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow…

When they finished the scene, Damiano placed the cigarette in his mouth so that he could clap slowly, emphatically, and then said to me, confidentially, “Not bad, huh?”

“Huh,” I replied. “Not bad.”

“Give me a sec,” Damiano said gruffly, having taken the bait, and went to have words with his charges.

Once the pair had left, Damiano flipped one of the chairs around and straddled the seat. He had a Styrofoam cup in one hand; he took a final pull at his cigarette and then dropped the butt in his coffee. “I hear you’re in the new Hornbeam picture.” When I nodded, he said, “I’m not crazy about his work,” as if he’d recently had to turn down a starring role with him due to other commitments. “What’s he like on set?”

I considered playing dumb, to confirm that I took such experiences for granted. But I recalled an exchange between Diane Lane and me during my first day of shooting, in which she shows me a shortcut to factoring and I steal a glance at her profile as she writes out the solution. “Look at her,” Hornbeam said after the first take, “like you’re cheating off her test but want to get caught.”

“He’s precise,” I said, my precision surprising me. “He points you exactly where to go.”

The answer drew a jealous smirk. “Lucky you,” he said.

I let that one hang.

“Speaking of luck,” Damiano continued, “I need a role filled in our spring production of As You Like It. Plan to be here from nine to five every Saturday for the next month.”

It took a second to process this horror. “What if I don’t want to?”

“You don’t have a choice,” Damiano said.

“What if I have detention this weekend?”

“Come afterward,” he said. “We’ll roll out the red carpet.”

From his back pocket, Damiano produced a paperback copy and flapped it at me, which to my disgust was warm to the touch.

“Don’t worry,” he said, “it’s a small part. A couple of scenes in the first act. Important role, though. Charles. The wrestler.” When he registered my displeasure, he smiled and added, tauntingly, “A little typecasting.”

That afternoon, I had ninth period free. I was sitting on one of the front hall pews and feeling sorry for myself about my lost Saturdays. Rob Dolinski, a senior, sat across from me. He had his arms stretched out on the pew’s back crest, over the shoulders of his usual sidekicks, or girlfriends, Andrea Oppenheimer and Sophie Evans. Sophie was freckled and broad-mouthed, and she almost always wore pants—she so rarely donned a skirt with her blazer it was practically an event. Andrea, a beauty in a black turtleneck, wore her chestnut hair parted down the middle, half veiling her large eyes, the ends cut so that they appeared sharp and nearly pinched together, like a staple remover’s teeth. Earlier, they’d come in from the sublevel carport across the street, “under the stairs” where everyone went to smoke cigarettes.

Mr. McElmore, who ran marathons, came into their line of sight. Runners in general, and their outfits in particular, were outlandish back then, especially since they were on the continuum of nearly naked. McElmore wore super-short shorts, shiny as silk, and a nylon tank top. He had on what looked like a cycling cap, with its tiny brim turned backward, beneath which he’d stuffed his curls. His skinny, shaved legs were as taut and muscular as a Thoroughbred’s, and above his ankle socks each cord in his calf caught the hallway’s light. He stopped to talk to a passing student.

Dolinski whispered something to Andrea, who bent double. She laughed so hard, but also silently, having blown all the air from her lungs. When Andrea, leaning over Rob’s lap, cupped her hand to Sophie’s ear and shared, Sophie said to Rob, flatly, “I dare you.” At which point he stood and, tiptoeing right up behind McElmore, delicately pincered his shorts at the hems and then yanked them to his ankles.

For a moment, McElmore didn’t react, just stood like the vase on a tablecloth the magician rips away. Because his shorts had built-in lining and he was now butt naked. The stubby shaft of McElmore’s penis rested atop his nuts; it was so squat and fat it pointed straight forward. It looked like a cannon from the Revolutionary War—the barrel dwarfed by its wheels. I had never seen one like it. Clearly Dolinski hadn’t either—or had expected briefs and not the head of admissions’ bare ass and strange dick—since he stepped back, covering his mouth. Andrea and Sophie had also covered their mouths. McElmore bent to pull up his shorts, and when he finally did speak, it was without anger, although his port-wine birthmark had flushed a deep purple.

“Dolinski,” he said, “you asshole. Report to Saturday detention until you graduate.”

Which meant that I’d at least have some company this weekend.

As if God were also punishing me, it rained all the next morning. The weather put the film crew in a bad mood, since it threatened to scotch the schedule and slowed setup for our exterior shots. It sank me into despair, because today was when Amanda was supposed to visit. At the town house, after makeup, and in between bouts of woe, I passed the time studying my lines—not for my upcoming scene, since I had those down, but rather from As You Like It.

Oliver: Good Monsieur Charles, what’s the new news at the new court?

Charles: There’s no news at the court, sir, but the old news; that is, the old duke is banished by his younger brother the new duke; and three or four loving lords have put themselves into voluntary exile with him, whose lands and revenues enrich the new duke; therefore he gives them good leave to wander.

This was why Damiano said I was an important character: I filled in crucial backstory. On Freytag’s Pyramid I was Mr. Exposition. In this scene, I was preparing to wrestle Oliver’s brother Orlando. My line in the next scene, right before the wrestling match, was a great one: “Come, where is this young gallant that is so desirous to lie with his mother earth!” But apparently Orlando wins (“Shout,” the stage directions read, “CHARLES is thrown”). Which meant, I learned as I read on, that I was also the Inciting Incident. It wasn’t too much to memorize, although once again the thought of a month of Saturdays spent at Boyd made me want to bash in my skull. Worse, there was no telling when I might see Amanda next. Until the sun, blued by the window gels, kissed my paperback’s page, and I looked up to see that the sky had cleared.

It was one of those April days in New York when the warmer breezes carried on them the estuarial tang of the city’s surrounding rivers. Parked cars sparkled with beads of rainwater, and the puddles, like mirror shards, reflected pieces of skyline before being splashed to bits by traffic. Outside now, waiting on my mark as the crew tweaked the reflectors and spots and held up a light meter to my face, I watched the asphalt dry and then brighten. At the end of the block, like a Seurat in progress, Central Park was dotted with greens and browns and stony grays. A crowd had already formed at the police barrier. The camera crane rose high above the street, its four outrigger floats like a plesiosaur’s flippers shuddering under its weight, and with the cinemaphotographer, Willis, and Hornbeam both in the basket, and the long lens protuberant between them, the machine looked like a three-headed monster from The 4:30 Movie.

After being deposited back on earth, Hornbeam said, “Run through, please,” and, taking his mark beside me, called out, “Action.” We began to stroll down the block, the cued extras walking past us. In the scene, Konig and I had just come back from having a catch in Central Park. I was still wearing my mitt and throwing the ball into its web, while Konig, in cords and a blazer, had his tucked under his arm. I was heartsick over Diane Lane and doing my subtle best to get some guidance from the one person least equipped to offer it:

Bernie

How’d you know you’d fallen in love with Mom?

Konig

Because after we met, she was all I thought about. Kind of like a cancer diagnosis.

Bernie

Did she feel the same way about you?

Konig

She said that as long as she was acting in my movie, she wouldn’t date me. So I fired her on the spot.

Bernie glares at Konig, shocked.

Bernie

Then what?

Konig

I took her out to dinner that night and hired her back after dessert.

Bernie

The girl I like doesn’t know I exist.

Konig shrugs at this insurmountable problem.

Bernie

How do you fix it?

Konig

The same way you treat male pattern baldness. Look, Bernie. In matters of love…

A Beautiful Woman walks past father and son. Konig, Slowing Down, turns to Watch her progress.

Konig

…maybe let the game come to you.

I looked up to see Amanda standing at the barricade and leaning her elbows on its beam. She waved at me excitedly, and because the scene had ended, I went to join her.

“This is amazing,” Amanda said. “Aren’t you nervous with all these people watching?”

I scanned the crowd. “I don’t really think about it,” I said.

“You never get stage fright?”

“Only when I talk to you.” Which was, I could not help but notice, the most forthcoming thing I’d said to her since we’d met.

“And who is this young lady,” Hornbeam said, “consorting with such a poorly mannered host?” He was standing behind me, waiting for an introduction. After I made this, Hornbeam lightly took her elbow. “Why don’t you stand over here with the crew?” he said, and touched her crown as she ducked under the barrier. “Or better still, how would you like to be in the shot?”

Amanda looked over her shoulder at me and widened her eyes in disbelief. I shrugged, as if to say, Good luck. Hornbeam, as if he’d been planning this for some time, led her to where the beautiful extra stood. I watched as Hornbeam sawed his hands, giving them direction. As Amanda listened, a shyness left her features that made her appear older. When Hornbeam returned to my side, he explained how the scene was going to change. When we rolled, Amanda and the extra walked side by side, playing mother and daughter, chatting as they passed us, and this time Hornbeam and I both turned to regard them. During one of the final takes, Amanda smiled at me as we passed each other—this being the shot Hornbeam ultimately used—alluding, I thought, to something that hadn’t happened between us yet, as well as to these unanticipated circumstances that put us where we were: on set, in this scene, and, when I thought about it during the film’s premiere, forever.

Later, we took the crosstown bus together. Amanda remained quietly elated. We were seated in the back, Amanda by the window, which she’d slid open. “Not in a million years,” she said, “would I have thought I’d be in a movie today.” We entered the transverse, and the park’s leaves flashed past like a green wind. She watched this blur for a minute and then turned to face me. “You are full of surprises,” she said. She scanned my eyes after she spoke, as if to confirm a suspicion, and I experienced the dual feeling I would so often suffer in her presence: that she was waiting for me to do something and that to do so would be a complete mistake. Which is to say that my ear’s blood beat was as loud as the bus’s gargle. “Why do you get stage fright when you talk to me?” she asked.

I shrugged.

“Am I so horrible?”

I shook my head. “I worry…” I said.

“That?”

“I’ll say something wrong.”

When I didn’t elaborate, she said, “And?”

“You won’t like me anymore.”

Amanda raised an eyebrow. “What makes you think I like you?” To my horrified expression, Amanda said, “I’m kidding,” and knocked her shoulder to mine. She turned chatty. Here was the difference between Amanda and every other girl I’d known so far. She noticed things I hadn’t realized I had until she spoke them aloud. That on the city’s East Side, for instance, the crossing islands are more beautifully manicured, but nobody sits on them. That at night its avenues are deserted, but Broadway always seems crowded. That the East River, she observed, is half as narrow as the Hudson but more menacing. “Do you know what I mean?”

I did. “I do,” I said.

“This is our stop,” she said, and pulled the bell string.

We got off and waited together again for her northbound bus, which appeared on the hill’s crest far too soon. I was gathering the courage to ask her out when she beat me to the punch.

“Want to come babysit with me next week?”

I held out my open palm, which delighted her. “Write down the address.”

That evening, Oren, Mom, and I went to see Dad rehearse his new show at the St. James Theatre.

The cast was seated onstage in folding chairs, with the four principals, including Dad, in the front row. All of them had binders in their laps. But for an upright piano downstage left, the space was bare. The rear curtains and backdrop were raised to reveal the far wall’s exposed brick, which made the stage seem bigger. A fissure, patched with pale mortar, ran diagonally across its face.

A small man wearing a jacket and tie shuffled in from the wing; he was greeted by applause and raised his hand to the audience of friends and family, and then stood next to the instrument for a moment in acknowledgment. Mom leaned toward my ear as she clapped and said, “That’s Hershy Kay, he wrote the music for A Chorus Line.” He reminded me of Elliott, as round and solid as he was, his countenance at once impish and formidable, this intensified by the occasional flash from his glasses’ lenses when they caught the light. He had a full head of white hair and full lips, and when he bowed it was more a gesture toward one: he lightly tapped his palms to his hips and bent ever so slightly before taking his seat at the piano.

José Ferrer—“He’s the director,” Mom said, “he was very famous for his role as Cyrano”—followed Kay onto the stage. He was tall. Imposing. There was a dashing regality about his bearing. He had a goatee, and his mustache was wide and dramatic as a musketeer’s. He even bowed like a swordsman, hand to chest and the other arm stuck out, toe pointed daintily toward us as he bent at the hips, which indicated a surprising agility and also got a laugh.

Abe Fountain, whom Mom knew I recognized and simply glanced at me as the applause rose in response, walked on last. I had not seen him since Christmas, and I was struck again by how noticeably he’d aged since The Fisher King. He’d already donned his white gloves, a long-standing habit to protect against biting his nails; and while he was the youngest of the triumvirate—he was only sixty-three—his mannerisms suggested the greatest fragility. He touched one hand to his heart in a gesture of gratitude. I think often about these men, on that particular night, because there was an old lion’s grandeur about all three, their great careers attending them like page boys, widening behind them like a wake, and I was touched by the fact that their confidence in this new project, their hope for it—a hope that my father wholeheartedly embraced—was fissured like the backstage wall, was belied by their self-consciousness during these introductions. By their awareness that this show might in fact be their last. So that even here, at the start, the rehearsal had about it an aura of a curtain call. But there was another layer that made these introductions so memorable. These men were so obviously one another’s people, a family, as Al Moretti liked to say, that they chose. They had gravitated to performance, here, to the stage, as a means of belonging. Here, where they put on the masks that, in some cases, others had made for them, masks that had, by now, grafted to their skin, behind which they were at once safe and allowed to be successful. Here, where they could be at home and hide in plain sight, until opening night, when the world decided, once again, whether it approved.

“Good evening,” Fountain said. “We appreciate you joining us for this musical run-through of Sam and Sara.” There was another round of applause, which Fountain tamped his hands to shorten. “Our plan tonight is to get through all the numbers with minimal interruption. Be warned, however, that we may pause here and there for all three of us to make some comments—breaks I hope you don’t find too distracting. So, without further ado…Sam and Sara.”

There was no dimming of the lights, no orchestra making the final clatter of readjustment in the pit. Only Kay’s accompaniment, the instrument sounding small and tinny in the comparatively empty space, accompanied in turn by the chorus as they stood to sing the first number, which took place, so far as I could figure, at a college campus, but it was difficult to tell without costumes. It was made more confusing the moment the show’s pair of stars took their place center stage, and the blocking was important. They stood alongside my father and the woman playing opposite him, but each slightly in front of the other. A couple coupled off. And they were noticeably older than their partners. Olivia White played Sara, the love interest. Her voice was raspy and tarred, and she sang in a register that was closer to speaking. Her gestures were at once spunky and feminine, and there was a hint to all of them of impersonation and overemphasis, like a girl playing dress-up. “She starred with your father in Oliver!” Mom whispered. “She was Nancy to his Bill Sikes.” Marc Morales, who played Sam, was chestnut-haired and towering, with a slow swing to all his movements. He had a booming singing voice—“He’s a star at the Met,” Mom said—that was operatic and in heavily accented English. His fingers, when he extended his thin forearms, visibly shook.

The number concluded, the applause’s volume described the audience’s size, Oren leaned forward to catch my eye and thumbed toward the aisle.

“Where are you going?” Mom asked us when we stood.

“Around,” Oren said.

We passed the remainder of the rehearsal as we had so many run-throughs of former shows. We climbed to the balcony’s highest seat, so that we could look down upon the cast members’ heads. We visited the empty lobby. We snuck behind the mezzanine’s bar, and Oren got us Cokes from the fountain, though there was no ice and the soda was flat. Via the wings, we climbed the catwalk’s ladders and crossed its bridge, pausing in the middle and leaning on its railing to watch another song. We snuck into the orchestra pit, which seemed cramped even without the instruments and musicians, while above us the performers sounded muffled and far away. And later, as we lounged in one of the dressing rooms, as Oren did pull-ups on the exposed pipes and blackened his palms with grime, I thought about how much I’d have liked for Amanda to see this place. I had the strange and incongruous fantasy of the pair of us living here, as if it were our own apartment, sharing the tiny bathroom, cooking small meals on the hot plate, reading the dated graffiti scratched onto the ceiling above our tiny loft bed. And I was flooded with love for her.

Dad wanted to go to Chinatown after the rehearsal was over, surprising Oren and me. “How about Hung Wa?” he suggested to Mom.

She appeared surprised as well. “That sounds great,” she said. “What do you think, boys?”

We took a cab again. It was a long ride, but Dad didn’t seem to notice the meter. He talked to the driver animatedly. In the back seat, Mom, Oren, and I were silent, lest we somehow change Dad’s mind. It had been a family tradition when Oren and I were little to eat at Hung Wa every Saturday night, but this had ended once we moved back to Lincoln Towers. The restaurant’s walls were a drab, faded green, although there was a wall-length fish tank by the entrance to the kitchen that was brightly lit and filled with albino oscars and pygmy catfish and gourami. The waiter arrived with wonton strips and ramekins of hot and sour sauce and mustard. When the waiter returned with the pot of tea, Oren and I filled our small cups with two sugar packets so that the drink was overly sweet. Dad ordered for the table, the very same things he had for Oren and me when we were little: egg drop soup followed by chicken lo mein; for Mom, Chinese broccoli and the shrimp in special sauce; and for himself the beef short rib. Oren and I took a moment to look at each other full-on, amazed that he’d remembered.

“How’s the new tooth?” Oren asked when he watched Dad eat.

“It’s a temporary,” Dad said, “but it seems to be working great.” He asked Mom, “What’d you think of the show?”

“I loved your numbers.”

“But what about the whole thing?”

“It’s early,” Mom said, and blew on a broccoli stalk. “It’s hard to tell.”

“It’s an incredible array of talent,” Dad said.

“They’ve all had great careers,” Mom said.

“Marc gets going and the hair stands up on my neck,” Dad said.

“His pronunciation when he reads his lines is terrible,” Mom noted. She finished her wine and, catching the waiter’s eye, pointed at her glass.

“Olivia’s still a gorgeous gal,” Dad said.

To me, Mom said, “Pour me some of your soup,” and handed me her teacup.

Dad said, “It’s hard not to feel good about things.”

“You should,” Mom said.

“It’s hard not to be optimistic,” Dad said.

“To Sam and Sara,” Mom said, after taking the wineglass from the waiter’s tray before he placed it on the table.

“To Sam and Sara,” we all said, and clinked teacups, which rang as dully as doubt.

The thing about the Saturday morning of Saturday detention was: getting up early for it felt earlier than getting up early for anything else. I was out the door and headed to school on my bike before anyone woke. Eagle-beaked gargoyles glared down on me from the spire of the Museum of Natural History. In the morning light, the building’s facade was as white as salt. My book bag was heavy, the spring warmth and exertion made my back sweat, my bitterness only intensified by the promise of such a summery day spent entirely inside.

Entering Boyd’s darkened lobby, it took a moment for my eyes to adjust. I wheeled the bike to the front hall’s pews and then sat, feeling oddly ashamed and utterly disgruntled. Detention began at eight, and, backlit as he entered the building, Dolinski at first appeared wraithlike. When he came into view, though, I could see he wore a suit and dress shirt, clothes that were entirely incongruous, although his hair was all over the place. He looked exhausted. He took a seat across from me and nodded.

“Am I late?” he asked.

From down the hall behind us, someone said, “You’re right on time.”

It was Mr. McQuarrie. He wore jeans and a Hawaiian shirt, plus a pair of two-tone monk strap loafers, and the sight of him in these mismatched civvies was inexplicably disturbing. On his index finger he spun a huge ring of keys. He looked positively delighted to be here.

In the book storage room, McQuarrie gave us instructions. Above, half the fixtures were switched off, so that the back of the room was shrouded in darkness. The walls, where visible, were lined with metal shelves, these containing rows of textbooks that disappeared down their length into the murk. Stacked on the floor before these were more boxes we were to open and inspect. “You see how these have been mishandled,” McQuarrie said, and squatted. He indicated where the cardboard appeared punched in. From his back pocket he produced a butterfly knife and twirled out the blade. He stroked the packing tape so that the flaps popped open with great force, like a tube of biscuits. Then he removed a book. “You see the result,” he said, and indicated where the binding’s top was bent.

“That doesn’t look so bad,” said Dolinski.

“Doesn’t look pristine either now, does it?”

From the box he removed a pink bill of lading.

“Sort the damaged books and stack the rest on the shelves. Then place the returns back in the box with the receipt and put them over there.” He indicated the far wall behind us, where more boxes were stacked.

Dolinski said, “What do we do when we’re finished?”

McQuarrie stood and reached between the shelves and flipped a switch. It lit the back of the room, which was stacked floor to ceiling with more boxes.

“You won’t,” he said. He left and then reappeared. “I’ll check up on you in a while.”

Then he departed.

Dolinski went straight to the back wall of boxes and began arranging them until they formed what was, for all intents and purposes, a chaise. He lay down on it and, after removing his blazer and rolling it into a pillow, crossed his arms and legs and closed his eyes.

“Turn off that light, please,” he said.

“Seriously,” I said.

“Is my helping going to get us out of here sooner?” Dolinski asked.

I sorted, I shelved. The work was so boring it was a form of torture. At 10:45, McQuarrie reappeared. He walked over to Dolinski, gently shook him awake, said, “Up, please”—considerateness that to me was astounding. “Who needs to use the dunny?”

We both raised our hands.

“Back in ten, please,” McQuarrie said.

We split up.

Wanting to kill time, I went to the first floor. To my left, the long hallway connecting the New School to the older wing was a solid hundred-yard dash. It was low-ceilinged and carpeted. I took a four-point stance, said, “Take your marks, set,” and then sprinted. Above me, the lights flicked past like in the Holland Tunnel. I let my form spring loose as I approached the far wall. After I tapped it, I turned and raised my hand to the cheering crowd. I took the ramp down, toward the cafeteria’s doors. Adjacent to it was the wrestling gym, and I entered. I walked to the mats’ edge and slipped off my sneakers. I shoulder-rolled to the end of the room and was so dizzy I had to wait for my equilibrium to reset. On my return lap, I shot single legs so fast my jeans squeaked. I felt the fitness I’d lost since January. I rolled onto my back and stared at the ceiling. I took several deep breaths. Listened to my racing heartbeat. The darkened room was as chilly as an empty church. I anticipated the upcoming season. That it was absent Kepplemen warmed me with a sense of possibility.

When I left, I walked the longest route possible I could imagine, hugging the chapel and then down the hallway past Miss Sullens’s room, when I heard the chatter of voices. I crept toward the one classroom whose door was propped open and from which a light shined, and then peeked into its entrance. Inside was the tech clique, mostly seniors, several of whom I didn’t know and several I did: Marc Mason, Todd Wexworth, and Hogi Hyun. A couple of middle schoolers: Chip Colson and Jason Taylor. The giant sophomore wrestler Angel Rincondon. They’d arranged the long tables into a giant rectangle. It was body-warmed in there, fragrant. A couple of pizzas had just been delivered. The top box was open. There was a roll of paper towels for napkins and a pair of two-liter Pepsis next to a stack of Styrofoam cups. In front of each person was a spiral notebook, a handful of arcane handouts, and dice of all sorts of hard-candy shapes and sizes. The blackboard behind them was covered with drawings of mazes and maps, and I noted that Wexworth at the far end of the table seemed the leader of sorts and sat behind several folded-open cardboard screens, each one elaborately decorated, ancient skeleton armies in battles beneath the crenellations of a castle, an elf kneeling on a demonic statue, prying an emerald the size of an ostrich egg from between the tip of its forked tongue.

Marc Mason, one of maybe five Black kids in the upper school, rocked back in his chair. He appeared mildly annoyed. Whatever I’d interrupted was very serious business.

“What’re you guys doing?” I asked.

He had not only folded his slice but also the paper plate on which it rested, as if he were going to eat both.

“We’re about to try to kill an ogre,” he said, indicating the rest of the group. “You’re welcome to stay and watch.”

When I told him I was on detention, he said, “Rain check, then.”

The following Monday, after I finished shooting that afternoon, I babysat with Amanda.

The building was a small four-story walkup above a grocery store, on Amsterdam Avenue and Seventy-Fourth Street. The stairwell, dimly lit, was narrow and creaky. It wound tightly on itself, each landing bookended by a pair of apartment doors, each with a peephole framed in ornamented metal. I was so nervous and excited to be alone with Amanda in a place where we were not moving, I could barely swallow. With each step, I vowed today was the day I would say no to doubt, I would trust my feelings, like Ben Kenobi urged, I’d speak up and ask her out. I knocked on the door, which Amanda opened and said, with real surprise—and did I detect the tiniest note of dread?—“You’re here!” And then she led me into the smallest apartment I’d ever seen.

Absent the half bath, it was a single room. Which in and of itself would be unremarkable were it not for the fact that three people lived here. In English the following year, when we read Crime and Punishment, I’d learn that such an apartment was called a “garret,” and I would picture Raskolnikov in this place, drinking from the tap in the kitchen’s tiny sink, all his dishes stored in its single cabinet, to then take a seat on the two-person couch adjacent the front door, his stationery placed atop the gameboard-sized coffee table. The dormer window that faced north was blocked by a dresser; the one facing south was half filled by an AC unit. Beneath this was a twin bed with drawers in its frame. Did the parents of Amanda’s charge sleep head to foot? The other bed, catty-cornered to it, was piled with stuffed animals. The little girl Amanda babysat lay belly down on the floor in front of the television, which was also on the floor. She rested her chin in her hands and had folded her raised ankles one over the other. She looked over her shoulder at me but did not say hello.

“Can you tell Griffin your name?” Amanda asked.

“Suzy,” the girl said. Then she returned to the screen, whose image began to float vertically before she adjusted the TV’s antenna and bopped its top before it reset itself.

Amanda shrugged and tapped a cushion next to her on the couch. Above her top lip, perhaps because I planned to kiss it, I noticed for the first time its thin layer of blond down. Amanda was wearing her school uniform but had taken off her shoes. She rearranged herself, tucking her feet beneath her, and then reopened her binder and math textbook on her lap, which sent a signal for which I was not prepared, since their jackets seemed to wall her off from me. In a ringing tone she said, “Welcome to my job!” and this too rang false. When I asked how often she babysat, she said usually four times a week. She explained that Suzy’s mother managed a restaurant during the day and her father bartended at night, so she covered the gap. I asked how old Suzy was, and Amanda said to her, “Suzy, tell Griffin how old you are,” and without turning around she answered, “Six.” Manners, Amanda mouthed, and gave a big thumbs-down.

The 4:30 Movie was on. Amanda said, “Suzy, tell Griffin what you’re watching.”

Suzy said, “Gamera vs. Godzilla.”

The monsters were about to do final battle. The Japanese were running for cover. Their army’s laser cannons were having no effect. We watched in silence. It was the moment to ask Amanda out, but before I could speak, she said, “How’s Take Two going?” and kept her eyes fixed to the screen as if it were an Academy Award–winning picture. I told her this was probably my last week of shooting, but it was going well. There was another pause, and I said, “I was wondering—” but Amanda interrupted me to ask what I’d done over the weekend. I told her I’d had play rehearsal. When I asked her what she did over the weekend, she said, “I went to Studio 54 on Saturday and spent Sunday recovering.” She remained plastered to the television so I, baffled, turned to watch it too.

It was the movie’s climax. The city lay in waste about the two monsters. Gamera was calling upon his ancient powers to defeat Godzilla. From the sky there descended a cone of energy that supercharged the turtle in light. It was now or never, I thought, it was time to summon my courage, and then Amanda and I said to each other, “Do you—?” at the same time.

Amanda blurted, “Jinx!”

Rules dictated I could not speak.

“Do you want to know the craziest coincidence?” she asked. When I nodded, she said, “You go to Boyd Prep…”

Gamera’s chest opened.

“…and so does my boyfriend.”

Gamera fired his super plasma beam at Godzilla.

“I think you know him…” Amanda said.

Godzilla was engulfed in the fireball.

“He’s a senior…” she said.

The smoke cleared. Tokyo was silent.

“Rob said he was in detention with you Saturday.”

Godzilla, defeated, thudded into the sea.