There Is No Try

And to this day I so rarely feel things when they happen. I remain so insulated from myself that, tucked away in my high tower or secreted in my dungeon’s ninth level (I’d play a lot of D&D that year), I barely detect the pounding on my heart’s three-foot-thick and twelve-foot-high door. And if I do manage a reaction, it’s still often the diametrical opposite of what the moment calls for. That evening, for instance, having left the garret apartment, I spied my idiot grin in storefront windows during my entire walk home, the same one, I imagined, with which I comforted Amanda after she informed me about Rob (“We can still be friends,” she said, to which I, like the actor performing an inflection exercise with my father, replied, “We can still be friends”), because she pulled herself to me immediately afterward, she hugged me with such force her textbook and binder fell to the floor, she pressed her bare knees to my thighs and gathered me into her arms with so much relief that I allowed my upraised arm to relax, finally, and fall to her shoulder, to revel in her warm forehead against my neck, and I held her too. And having what I’d so desperately wanted before I could even begin to process what I could not, my countenance must’ve set up like Quikrete (“I was so worried I’d lose you,” she said, smushed against me, to which I replied, “You’re not going to lose me”), my expression of shock froze into rictus and dried my teeth, my grimace made my paralyzed cheeks sore and must’ve given me an oxymoronic appearance—gleefully grim, dismally delighted—because upon first regarding me when I got home, Oren asked, “What happened to you?”

“Nothing,” I replied, which was true, in a way, and I retreated to my study to stare, quakingly quiet, at my corkboard’s collage and ask the simple question I still find I most often do when it comes to love, which is “Why?”

There is a second stage to this process, a special brand of sublimation, which occurred later that week and altered my fate. Like quite a few things that happened in my youth, it is also something you can watch on YouTube: a scene from Take Two that’s a famous tearjerker, like Ricky Schroder’s with a dead Jon Voight in The Champ. We shot it my last day on set. It takes place in Konig’s dining room, now his ex-wife’s town house. He has brought Shelley Duvall to dinner, with whom he has patched things up. He has figured out the ending to his movie, and he’s elated because he’s secured financing for his next picture—which, he informs the guests, he’ll shoot on location in Spain. Clayburgh, meanwhile, has struck up a relationship with Elliott; Gould holds her hand atop the table, he is so in love. Like Konig, Clayburgh is also in high spirits. She’s just landed a major role in a Bertolucci film—she is out from under Konig’s shadow, she’ll spend most of the upcoming winter in Italy. It is all at once authentically celebratory and also a game of one-upmanship—in other words, decidedly adult. The scene is shot tight: the camera tracks right, in what appears to be a circle around the table; it loops, swinging back, with each piece of happy news, to my character, Bernie, to whom no one is speaking, who is registering his progressive abandonment, and who can’t help himself finally—at the scene’s climax, he smacks the table. Everyone turns to look at him. The camera fixes on him, in close-up, and, eyes full of tears, he says, “Why did you bother? Having kids. Me. What was the point? Jesus Christ, I’m like Charlton Heston in Planet of the Apes. This whole time I’ve been thinking I’ll finally get back to Earth when this is it. This is my home.”

Nailed it on the first take. And after Hornbeam held the shot at its conclusion, I just broke down. I couldn’t get it together, even after Hornbeam yelled, “Cut,” and the entire crew erupted into applause. Even after Hornbeam, who, along with Jill and Shelley and Elliott, rubbed my back until it warmed my shirt, and even Diane appeared and put her arms around my neck—here too my sobs turned to laughter. I laugh-cried myself into comfort. I knew I’d done something excellent, but everyone’s appreciation sounded far off; and not for a second did it occur to me that the sadness I’d so torrentially tapped into came from elsewhere.

“You decide to become a great actor,” Hornbeam said to me later, “and nothing’s going to get in your way.”

Perhaps Oren was right after all.

Now, however, back at Boyd full-time, I devoted myself to a detailed investigation aimed at answering the following question: Why was Amanda in love with Rob Dolinski instead of me?

There were obvious and glaring differences between us. There was, first and foremost, the figure he cut. He was easily over six feet tall, with a classic swimmer’s frame. His dark double-breasted suits accentuated this—he even occasionally wore a vest—their tailoring, cuffs to hems, imparting to his movements lines that cohered in a geometry unknown to me. He had some of the actor in him too, evinced by his choice of tie or shirt, one of which (or both) was always light blue, and had the effect of turning on another light behind his already bright eyes, which like a husky’s were hard to look away from. But looking away was one of Dolinski’s most devastating weapons of seduction: in the mornings, say, upon entering Boyd’s bustling front hall, Dolinski, midconversation—with a teacher, perhaps, or with whomever he’d happened to walk into the building—made it a habit to shoot a glance, midsentence, at some girl his junior, who’d been trying very hard (she too midconversation and seated on the pews with several half-huddled friends) to intentionally ignore him. But having felt the flash of him and confusing, as Elliott liked to say, her hope with her evidence, she’d meet his gaze full-on. And like the proverbial deer she then froze in anticipation—of a smile, a nod, some sort of acknowledgment—but was flattened by his dismissal, by the complete and utter indifference with which he strode past.

The most impressive thing about him was not his poshness, which I considered the definition of Upper East Side (and corroborated by checking his address in the Boyd directory, the Carlyle—“a very well-appointed building,” Dad had remarked when I asked), but the fact that nearly all the teachers adored him. I often spotted him lounging in Miss Sullens’s office, chatting about books. He’d pulled down Mr. McElmore’s pants, but they could be seen yukking it up as they waited in line together at Kris’s Knish, parked just inside Central Park, on Ninety-Sixth Street, as if it had all been in good fun.

“Just have one more look,” Dolinski pleaded with Mr. Heimdall as the two departed the chemistry lab.

Heimdall, mock annoyed, briefly eyed the marked-up exam Dolinski held. “You’re determining the concentration of sulfuric acid, Robert, not interpreting a passage of Shakespeare.”

To which Dolinski replied, “Compounds can be as elegant as sonnets.”

“Be that as it may,” said Heimdall, smirking with real affection, “come by at office hours. I’ll be easier to butter up then.”

Miss Brodsky—this was mind-boggling—once took his arm. Dolinski was standing by the front-hall pews, talking to Sophie and Andrea, when our permanently unfriendly IPS teacher sidled up to him, clutched his elbow, and, in a gesture that was both girlish and motherly—was, when I thought about it, Naomi-ish—pressed her shoulder to his and tilted her head as if she were going to rest hers there.

“Well, well, well,” Brodsky said, to the ladies as much as to him, “look at you, all grown up and handsome. Do you remember what a terror you were in ninth grade?”

“Yes,” Dolinski said, with a generous, self-effacing batting of his eyes, “and I also remember you being my favorite teacher.”

“You and your sweet lies,” said Brodsky. And then she noticeably gave his arm an extra squeeze. “You almost make me want to be a different woman.”

One afternoon, I spotted Sophie, Andrea, and Dolinski leaving the building, so I followed them. They were headed “under the stairs,” to the carport that was at the bottom of a ramp between two buildings on Ninety-Seventh Street. I too descended, breathing the trio’s smoke, which wafted toward me as I tapped the iron railing on my way down the steps and, once arrived, and having no idea what I was doing, took a spot at the far end of the space across from the three upperclassmen, leaning against the wall and trying not to be too obvious about my out-of-placeness. I glanced, now and again, toward the stairs, as if my buddy were arriving any second. At first the trio paid me no mind, but it wasn’t long before I had their attention.

“Waiting for someone?” Andrea asked me.

“Dude’s a narc,” Sophie said, and then, like my grandmother, tusked smoke through her nostrils.

“It’s Griffin, right?” Dolinski said. Then to Sophie: “He and I were in detention a couple of weeks ago.”

I was shocked he remembered my name.

“McQuarrie,” he said gloomily, “was our proctor. He never did get around to tying us up in his little dungeon down there, did he?”

I shook my head, disarmed by the olive branch of his inclusion.

He said, “You wrestled my friend Vince Voelker. From Dalton.”

“I guess you could call it that,” I said.

For Dolinski, smoking was an art. Even I, who’d never taken a single puff, could appreciate his grace. He took in each lungful with gusto, as if he were testing his wind, letting it float out on his words as he spoke. “He told me you were one tough nut.”

My heart had been bruised by Amanda, it was true, but I couldn’t help finding this cheering.

“I still think he’s a narc,” Sophie said.

Mr. Damiano appeared. He was greeted by the trio warmly, familiarly. When he spoke, the unlit cigarette in his mouth jumped like a seismometer’s pen. He was offered a light by Dolinski—his Zippo tinging when he opened it and whose scent of butane also reminded me of my grandmother. He covered the flame with his hand, even though we were hidden from the wind. Damiano, acknowledging my presence, said, “Your date not show?”

I shrugged.

“Griffin’s in my spring play,” Damiano said to the trio. “And the new Alan Hornbeam picture.”

“An actor and an athlete,” Sophie said, and stamped her dropped butt. “Can he dance too?”

Dolinski shook his head at her, then flicked his cigarette to the ground and, chuckling, dragged his sole across it. “You are such a bitch,” he said.

“What he can do,” Damiano said, “is squander his talent playing a superhero.” Then he reached into his blazer’s breast pocket, produced his pack of cigarettes, and, shaking one out, extended it toward me. “But I’m trying to change his evil ways.”

“Well, you know what they say, Mr. Damiano”—I bit the filter between my teeth, cupped my hand over Dolinski’s flame, and, before inhaling, repeated an observation I’d heard my dad make a thousand times—“those who can’t do, teach.”

A ghost filled my lungs. Its steamy form draped itself against my chest’s cavity. Its barber-hot towel softly stuffed my ribs. Its billowy expanse, rising up, wanted to escape my throat; and I finally let it, in one great arrow-straight stream that hissed past my lips, this imitation of a seasoned smoker so spot-on I appeared like some street urchin who’d taken up the habit at ten.

“Be seeing you,” said Dolinski.

“Later, narc,” said Sophie.

“Nice to meet you, Ethan,” said Andrea.

“Rehearsal this weekend,” said Damiano, and pointed at me.

I flicked the butt to ash and, in a farewell gesture, winked at them as they took the stairs. As I watched them ascend, I felt the color leave my face and the blood abandon my buzzing brain. The moment they were gone, the nausea rose up while I bent double, palms to knees, and with a terrible gargle sprayed the carport with puke. There came a second gushing heave. And then with my back arched, I spewed a third time. I wiped my mouth and then flung my last cigarette ever onto the puddle, spitting several times at the mess. Spitting through my watery eyes. Spitting at the man that, to Amanda at least, I was not.

Several weeks passed. Spring was in full bloom. Central Park was the forest of Arden. As You Like It was about to premiere. I’d taken Marc Mason up on his offer to join the game in between rehearsals, and was deep into the D&D campaign. I almost ran into Naomi. One Saturday afternoon, on the way to Gray’s Papaya for a couple of hot dogs, I spotted her at the Greek diner, seated at a table in the window, with, of all people, my mom, as well as her daughters, Danny and Jackie, the four of them yukking it up like a group of ladies who lunch.

Did I long for our talks, as lovelorn as I was?

I most certainly did not. Now that Amanda had told me about Dolinski; now that, at her request, we were “just friends,” she called me almost every night, and I lived for these chances. It was like being her boyfriend’s understudy; it made me hope he’d actually break a leg. She, as if to increase my already terrible confusion, made me hope. She was so forthcoming and sweet I could, if I cauterized my heart’s ventricles, pretend to enjoy myself. “Can you hear that?” Amanda said, cupping the receiver, which made her voice breathy and, somehow, nearer to my ear. “That’s my mom on her ham radio. Listen,” she ordered. There was a pause while she held the phone in the air. I could barely make out what her mother was saying. “She likes to talk to friends from Australia late at night,” Amanda said when she came back on. “Because it’s fourteen hours ahead. Do you want to know the crazy thing?”

I wanted to know everything.

“The longer she talks to them, the more her accent changes. And she picks up their expressions too. You know what ‘hit the frog and toad’ means?”

“No.”

“Hit the road. You know what ‘crack a fat’ means?”

I didn’t.

“Then I’m not telling you,” she said, “because it’s embarrassing.”

“Okay.”

“Unless you come babysit tomorrow.”

“Sure.”

Oren, on his way back from the kitchen, a bowl of cereal in hand, paused before my closet’s open door, shook his head at me, and, between spoonfuls, said, “Sad.”

I pulled the door closed so that Amanda and I wouldn’t be interrupted.

And I made it a point, after the previous evening’s conversation, to march straight up to Mr. McQuarrie the next morning so I could impress Amanda with my knowledge that afternoon.

“Sir,” I said, “I have a question only you can answer.”

McQuarrie spot-checked me, shoes to tie. “That’s a lot of pressure, Mr. Hurt, but I’ll give it a fair go.”

“What does ‘crack a fat’ mean?”

“Well, crikey,” he said, positively amused, “it means we’ll see you on detention this Saturday.”

Amanda could not stop laughing when I told her. We were at the garret apartment, and while she laughed, she pulled me close and cupped her hand to my ear, since Suzy was within earshot, and her touch sent a shiver straight to my soles. “It means,” she whispered, “get an erection.”

I blushed, and Amanda smiled. She adjusted her position so that she could lie on her side and place her ear on my lap. “This is nice,” she said. She curled into me. Her face relaxed. “Do you ever realize how tired you are all the time?”

I did, and I let my hand come to rest on her hip. The window unit hummed. It was Anthony Quinn week on The 4:30 Movie. They were showing The Guns of Navarone. We were at the part when David Niven discovers his timers and fuses have been sabotaged and that there’s a traitor on their commando team. “This is a great scene,” I said to Amanda and Suzy, who was stretched out on the floor and looked at me, exasperated.

“You always do that at the good parts,” she said.

This was a good part, I thought, what with Amanda all to myself and my palm at rest atop her skirt. Because Suzy was near us, because I was afraid to move an inch, the actors’ voices sounded especially distinct and loud.

So what does she do? Niven says. She disappears into the bedroom, to change her clothes. And to leave a little note. And then she takes us to the wedding party, where we’re caught like rats in a trap because we can’t get to our guns. But even if we can it means slaughtering half the population of Mandrakos.

Amanda, drifting off, said, “Tell me what’s happening.”

As best I could, I tried to catch her up. The war hanging in the balance. The Axis’s plan to wipe out thousands of marooned soldiers. The elite team of commandos on a desperate mission to blow up the Germans’ top secret weapon, a pair of long-range guns housed in an impregnable mountain. And now a spy in the team’s midst.

She said, “It sounds exciting.”

“My parents went on their honeymoon with Anthony Quinn,” I said.

“So cool,” Amanda murmured.

“My dad was his voice coach.”

Did I think Dad’s adjacency to stardom might confer on me a sort of glamour in Amanda’s eyes—as if it might function as a sort of spotlight that revealed me, standing on her stage? I’d been in a Hornbeam picture, after all. Why did I need the assistance?

Softly, Amanda said, “I could fall asleep right now.”

Her eyes were closed, and I considered her profile. She was very close, very far, very still; I was very still, very happy, very sad. Oh, that tiny apartment, where we spent most of our time together. Of all the places in my memory that I’m certain would seem smaller if I revisited them, this one, I’d like to believe, would in fact seem larger, being, as it was, the site of one of my first and most tender acts. I raised my hand and stroked her hair. I slowly dragged my thumb across her temple, letting my hand rise slightly as it ran past her ear and, in an unbroken circle, settle again, to touch her once more, until her weight gradually sank, barely perceptibly, into my lap. An act that, imitating love, was the closest to it, at that moment, that I thought I could get. And one of the rare occasions I caught Amanda acting, because her fluttering eyelids were a dead giveaway: she was pretending to be asleep.

The following Saturday morning, when I showed up in the basement theater and reported to Damiano that I had detention, he slowly shook his head and said to the cast, “Take five, people.” Then he asked me, “Who’s the proctor?” When I told him I didn’t know yet, he said, “Let’s go,” and we marched upstairs to the front hallway and waited.

It turned out it was Miss Sullens. They spoke softly, and after exchanging a knowing look, first at me and then at each other, she gave me permission to skip.

“Don’t thank me all at once,” Damiano said as we walked back downstairs.

To which I replied, “I won’t.”

Since performances began next week, we were in dress rehearsal. Wearing a ruff, doublet, breeches, and hose, plus shoes like a pixie’s, I sat in the wings, feeling like a total asshole. But because we were doing two run-throughs today and my pair of scenes came early in the first act, I didn’t have to be back for the second performance until after lunch. Which meant that I could head upstairs for the next several hours and rejoin the D&D game.

Marc Mason, upon seeing me at the classroom door, considered my costume and said, “Well, at least you’re into it.”

Todd Wexworth, who was barely a pair of eyes above his Dungeon Master screen, said to him, “You hear the story about those guys that died in the sewers because they wanted to play live action?”

Jason Taylor, a British middle schooler playing a halfling thief, said, “I’m quite certain that’s a muh, muh—” He stammered on “myth.” “—apocryphal.”

Angel Rincondon, a dwarven cleric, said to him, “Actually, one of them was my cousin.”

Kazu Makabe, who was playing a ranger, said, “Can we resume, please?”

Chip Colson, a seventh-grade kid playing a ninth-level mage, said to me, “You bring money for pizza?”

I handed him a five.

“Throw in more,” said Hogi Hyun to me—he was playing a monk—“and I’ll give you a couple of my doughnuts.”

“I’m glad you’re here,” Marc said to me—he was playing a bard—“because I’m sick of two-handing your character,” which was what the group did whenever a player character was absent and a rare concession to Wexworth’s usually orthodox observation of the rules. Marc had saved me the seat next to his and, when I took it, slid me my notebook and bag of dice.

I was playing a half-elf assassin—I’d named him Sylvanus—whom Wexworth had boosted to the eighth level so that I wasn’t a drag on the party.

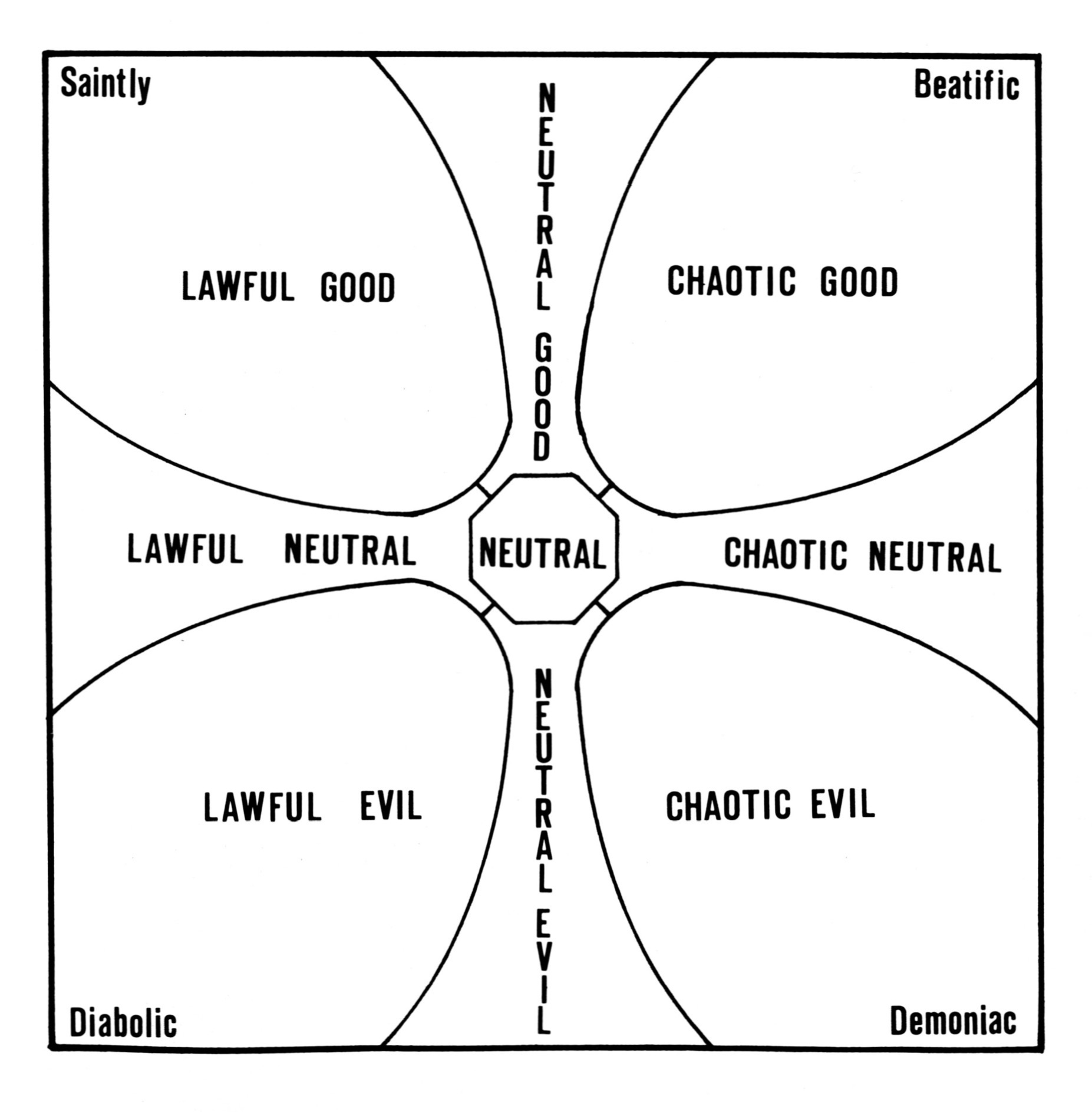

Play recommenced. We were seeking to penetrate the dreaded Tower of Marahall, and the party was forced to split up. Wexworth exiled Mason, Colson, and me to the hallway, where we took a seat. Mason, who was massive, gave his Afro several pokes with his blowout comb and then stuck it near his forehead, so that it looked like a samurai’s datemono. Fall to spring, he wore short-sleeved button-down shirts, a dress-code violation for which the faculty gave him a permanent pass. He was built like a linebacker and played power forward on the varsity basketball team. He was also a math student of some renown. This largeness he projected, the brains and the brawn, was nowhere near as impressive as his haughtiness. I figured we’d be outside for a while, so as we were leaving I asked Mason if I could borrow his Player’s Handbook to study while we waited. He said, “Fine, just don’t read my notes,” but I did anyway. There were fighting strategies and mnemonics regarding certain monsters and druidic spells. There were wicked cool diagrams, though by far my favorite was the Character Alignment Graph:

I could not help but analyze the souls of those nearest and dearest to me (Amanda: chaotic good; Fistly: lawful evil; Mom: lawful neutral, Dad: chaotic neutral, Oren: chaotic neutral).

“Why do I need to ‘be mindful of weather in outdoor combat’?” I asked, echoing one of the notes I had just read.

Mason, who was talking to Chip, held up a finger to him and said, “What do you think happens if you Call Lightning during a thunderstorm?”

Chip said to Mason, “Did you hear they’re going to add a new class of magic user this August?”

Mason scoffed. “No one’s seen the revised rulebook, you fucking nerd.”

“My cousin in Kenosha has,” Chip said. “He was at Gen Con last year and that was the rumor.”

“What’s the ‘Gen’ in Gen Con stand for?” I asked.

“Lake Geneva,” Chip said.

I didn’t know anything about anything. I didn’t even know where Lake Geneva was, or Kenosha.

“As you can tell,” Mason said to me, “Chip’s not getting a lot of action here at Boyd.”

Chip pushed up his glasses, then crossed his skinny arms. “Neither are you, blood.”

“Oh, snap,” Mason said.

Wexworth opened the door. “Gentlemen, will you join us, please?”

We stepped inside.

Everyone in the room looked upset, except for Wexworth.

When Mason took his seat, he said, “Don’t they have to leave the room?”

“No,” Wexworth said. “They’re all dead.”

I’d gotten so wrapped up in the game I’d spaced on rehearsal. Damiano appeared at our door and said, “Hey, asshole, did you forget something?” He waved for me to follow him, but as we were leaving the classroom, Mason called out, “Mr. D,” and caught up with us outside. “Can I have a word with Griffin, please?” And while Damiano stood in the hallway, fists to hips, Mason said to him, “It’s private.”

“Come to the theater the second you’re done,” Damiano said.

We watched him huff off.

Mason said, “You still don’t know what you’re doing in there.” When I started to apologize, he interrupted. “Cut the bullshit. I’ve got plans for your character but not if you don’t. So straight up. Do you want to play or not?”

I nodded.

“Then march your tyro ass to West Side Comics and buy the books. Don’t come back until you do.”

I started to walk away.

“And, Griffin,” Mason said. When I turned around, he added, “Read them.”

Which I did not. At least not at first. Late that afternoon, on the bus ride home from the store, I opened the Player’s Handbook to its table of contents and scanned its endless appendices and tables and charts and its preface, at which point I closed the book, cowed, and opened the Dungeon Master’s Guide. This was an even thicker, more intimidating volume, and as if it were a flipbook, I let its pages flap from front to back with my thumb and spied its index, its vast glossary of miscellaneous treasure and magic interrupted by pictures that were far easier to pause and dream on than the blocks of text were to peruse. And then, randomly, I stopped at “General Naval Terminology,” the first several items of which read:

Aft—the rear part of a ship.

Corvice—a bridge with a long spike in its end used by the Romans for grappling and boarding.

Devil—the longest seam on the bottom of a wooden ship.

Devil to pay—caulking the seam of the same name. When this job is assigned, it is given to the ship’s goof-off and thus comes the expression “You will have the devil to pay.”

Who knew? Not I, the ship’s goof-off. Caulking the seam until he abandons ship. Which I now considered. Or, if I were to stay, if I were to stick it out, at the very least I’d ultimately hand off that role to someone lowlier, yes? I took a moment to gaze out the window. We were passing the Museum of Natural History, the building’s footprint stretching two full city blocks, and in my mind, I was a child again. Mom had practically raised Oren and me there, we spent so much time racing through its corridors. I spotted the Seventy-Seventh Street entrance, our usual point of ingress, and a map of its levels, long ago memorized, floated before me in three dimensions, and I mentally made my way through the Hall of New York State Environment, past the log-sized earthworm and cross section of the redwood with its historical markers at each ring, through the Hall of North American Forests and the Hall of Biodiversity to my destination, the Hall of Ocean Life, where, after a loop around the mezzanine, I descended the wide stairs to the bottom level, where I’d lie on the floor, beneath the blue whale, feeling the subway rumble below, waiting until Mom and Oren finally caught up with me. And when they did, I would walk them past every diorama and, like a tour guide, supply the scientific name of every creature—Architeuthis, Physeter macrocephalus—my recall as perfect as a marine biologist’s.

I found Mom in her bedroom, seated at her desk, typing an essay she’d handwritten on a yellow pad. There were Henry James novels piled around her. Her Smith Corona hummed with current. She was a superfast typist, she didn’t need to look at the keys, and when she hit Return and the platen slid to the right, the whole table shuddered.

“Hey, Griff,” she said, and kept typing. “Did you sleep at Tanner’s last night?”

“No,” I said. “I was here.”

“Oh.”

“Where’s Oren?”

“He and Matt are at Dad’s studio.”

“Doing what?”

“Recording something, I think.”

“What does ‘q.v.’ mean?” I asked.

She paused to look at me. “I thought you took Latin,” she said.

I’d failed middle school Latin, which she just now recalled.

“Quod vide,” she said. When I repeated the phrase, still perplexed, she added, “ ‘See which.’ ”

“Like…the monster?”

“What?” she said, and squinted. Then she chuckled. “No. As in: ‘With regard to this matter, go see x.’ ”

“Ah,” I said.

She resumed her typing.

“What about ‘tyro’?” I asked.

She nodded toward the Merriam-Webster on the table. “Look it up,” she said.

Standing there, I flipped through the dictionary’s onionskin pages until I found the definition: “a beginner in learning anything; novice.”

“Can I borrow this?” I asked.

“Only if you bring it back,” Mom said.

Later, in our room, while I was studying the Monster Manual, Oren appeared.

“Yo,” he said when he entered. He was wearing sunglasses and his Walkman headphones. He was also carrying a bag from Tower Records. When I asked Oren a question, he pulled one of the earphones away from his head.

“I said,” I repeated, “why are you wearing your sunglasses inside?”

“Because I’m maxing and relaxing,” Oren said.

“Because you’re a douche bag,” I said.

“Because I’m…” He let the earphone spring back.

Melle Mel, right on time

And Taurus the bull is my zodiac sign

And I’m Mr. Ness and I’m ready to go

And I go by the sign of Scorpio

He popped and locked, did a bit of the Robot, and then slid the earphones around his neck. “Matt and I cut a single.” He held up the cassette. “Want to hear?” He slid the tape into our deck. A drum machine started up. Next, Oren and Matt alternated raps:

We’re the White Boys

We’re white as can be

Hey yo, my name O-reo

And I’m M-A-double T.

“That’s great,” I said over the song, “if you’re retarded.”

“You’re just jealous of our talent.”

“An Oreo isn’t as white as can be.”

“Fair,” Oren conceded.

“How about Matty Matt instead?”

“How about,” Oren said, “you join the group. You could be DJ McGriff.”

“Why the ‘Mc’?”

“Because you’re fast, like McDonald’s.”

The phone rang. Mom immediately picked up. Then she shouted, “Griffin, it’s for you.”

It was Amanda.

“I know this is last minute, but are you busy later?” she asked. Her voice was so bright and ringing it was close to shrill. When I told her I was free, she said, “My father’s in town and wanted to take me to dinner. He said I could bring someone.”

“Sure,” I said, and punched the sky. “What time?”

“Can you be here by six thirty? It’s probably a fancy place.” When I told her yes, she said, “Great,” and then gave me her address. “I’ll see you soon.”

When I hung up, Oren said, “You should come record with us tonight.”

“Can’t,” I said. “Got a date.”

“With who?”

“You don’t know her.”

“Maybe she lives in Canada,” Oren said. He produced the forty-five of Grandmaster Flash’s “Freedom,” touched the needle to the vinyl, and when the kazoos kicked in, he started dancing, so I joined him until the end of the track, because it was the only way to deal with my nervous excitement.

Later, I was leaving just as Mom was setting the table.

“Where are you going?” she asked.

“To dinner.”

From our bedroom, Oren shouted, “With a girl.”

“Oh,” Mom said, and smiled. “Just the two of you?”

“And I think her dad,” I said.

Mom gave me the once-over. “Then go put on some khakis and a button-down.” When I rolled my eyes she said, “Loafers too.”

“I’m gonna be late.”

“Go,” she said.

I lurched back to my room to change and shambled back for inspection right as Dad was pulling up his chair. “I hear you have a hot date,” he said.

“He’s meeting her father,” Mom said.

“He can’t wear that shirt then,” Dad said.

“Why?” I groaned.

“It’s wrinkled.”

“I have to go.”

He snapped his fingers three times quick. “Give it to me,” Dad said. He pushed back from the table and went to the kitchen. He emerged with the ironing board and folded open the legs, and its wire made its subway screech. He waved to me—c’mon, c’mon—to hand him the shirt, which I removed and then sat down on the couch, topless, burning with impatience and shame as my back stuck to the leather. He returned with the iron and plugged it in. The signal lamp was red. After another trip to the kitchen, Dad appeared with a can of spray starch and a measuring cup full of water. He carefully poured the latter into the iron’s nostril. He waited until the iron burbled and sighed. Dad did a cuff first, spreading it over the board’s nose, hitting it with some starch and a puff of steam, and then stretched out the sleeve, running the sole plate along its hemline with a couple of farty pumps of the spray button. I could see Dad’s reflection in the framed painting’s glass, the one above the living room’s console table of a bouquet that had survived the fire. His expression was focused and calm, and now, as he ran the iron’s nose between the shirt’s plackets, steam chuffed merrily from the machine. Then he flipped over the shirt to do the back. Finally, after setting the iron on its heel, he hooked the shirt by the hanging loop and held it out to me on his index finger. It appeared slightly boxy and sculptural. Buoyant, so that it twirled ever so slightly, like a mobile.

When I put it on, he said, “Better.” Then he kissed my forehead and patted my cheek. “Don’t do anything I wouldn’t do.”

I took the Broadway bus uptown. I sat in the back. Something about the starched shirt made me feel like I was in a costume. That my current determination for tonight to go well was also a put-on. That my resolve, as currently stiff as my shirt’s collar, would go soft and yellow the moment I was made to sweat. I stared out the window and took comfort in the familiar sights. The Seventy-Second Street subway station house, fashioned of granite and brick, exhaled passengers onto the crossing island where Amsterdam and Broadway intersected. The Apple Bank, the protuberant wrought-iron window guards of which were shaped like my grandmother’s suet feeders. Hanging braids of garlic swayed in the breeze above boxes of fruits and vegetables at the Fairway Market. We passed the Apthorp Building—it had an interior courtyard, visible through its entryway’s arch, before which Mom once took my shoulders to stop me in my tracks and pointed to an older gentleman wearing a bright silk scarf around his neck. (“That,” she whispered behind me, “is George Balanchine.”) We crossed Ninety-Sixth Street, and soon I was walking down Amanda’s block, the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine walling off my eastern view.

Standing in the foyer of Amanda’s building, I found West on the buzzer panel and pressed the button. Her mother said, “Who is it?” over the microphone. The moment I replied, the door buzzed and stayed buzzing for a good ten seconds after I’d entered. The lobby was dark. As I waited for the elevator, I noticed one of the bulbs in the overhead was dead. The floor was fashioned of black and white tile and smelled sharply of piss.

Miss West greeted me at their apartment door. “Come in,” she said, having already turned, and, waving, beckoned me to follow her down a narrow hallway. I noted a small kitchen to my left and, straight ahead, a bedroom whose door was closed and from which music played. I stepped through a pair of French doors to my right, into a living room, where Miss West took a seat on the sofa and an already lit cigarette from the ashtray. The wallpaper was gray, pocked and torn in places, and faded. The windows were soot-covered, and this further dimmed the light. It occurred to me, in a flash, that on the continuum of people I knew—from the Adlers and Pilchards and Dolinskis, to the Shahs and the Barrs and the Pottses, and then Cliffnotes’s family and mine—Amanda’s mother was the closest thing I knew to poor.

I extended the bouquet of roses I’d bought toward her.

“Oh, these are lovely.” Miss West ashed her cigarette and took the flowers in her free hand. She briefly smiled after considering them. “No wonder you’re not her type,” she said, and then strode to the kitchen.

I heard the plastic wrap crumpling (my heart), scissors snipping (my head), faucet running (my blood), a cabinet squeak and then bang shut (my hopes). The only illumination in the room came from Miss West’s ham radio, whose components sat on a catty-cornered desk, the faces above its several knobs backlit. Miss West had returned with a vase and placed the flowers on the coffee table. She was markedly taller than Amanda but also broad-shouldered; she had thick arms and she looked at me with something between disregard and pity. Her interest, I felt, could suddenly turn dangerous. She had blue eyes, larger than her daughter’s. She and Amanda shared the same complexion and coloring—she too was blond, though she wore her hair short—with identical noses, their tips lightly crimped down the center. But there the similarity ended. Miss West took a long pull on her cigarette, and the cherry flared brightly as it crawled down the paper. After she crushed it out, she said, “You’re the actor Amanda was telling me about. The boy who was in The Talon Effect. I loved that movie. Though I told Amanda I couldn’t for the life of me remember anything about your performance. Didn’t you play the son of Rip Torn?”

“You’re thinking of Roy Scheider. Torn played the double agent.”

“Is Rip Torn his real name? I’ve always wondered.”

“He told me it was a nickname.”

“It’s mostly the Jews who have stage names,” Miss West said. “Like Lauren Bacall. Or Tony Curtis. I have a friend I talk to in Hungary who keeps a list of them. You know Han Solo?”

“You mean Harrison Ford?”

“Jew,” she said. Then she looked over my shoulder. “Look who’s finally ready.”

I turned to face Amanda. I said hello, though I was not sure if the word came out. I realized, as I stared, that I had only ever seen her in her school uniform and without makeup. She waited between the French doors in a black dress and a pair of gold necklaces. She had pulled her hair back and tied it off. Her feet, tipped into black heels, made her as tall as I was. I thought of all the makeup chairs I had sat in, how other actors had what seemed a new face put on once they were through. But in Amanda’s case, in lipstick and eyeliner, what was revealed was the woman she would become, the thousand ships she might launch. That she seemed entirely unaware of this power’s limitlessness made it all the more impressive.

“You look nice,” I said.

“So do you.”

“Where’d you get that dress?” Miss West asked her.

“Dad bought it for me.”

“Well,” Miss West said, “there’s a first time for everything.”

The phone rang.

“I’ll get it,” Amanda said.

“Stay where you are,” her mother said, “smell the roses your friend brought me.”

Amanda froze as Miss West strode toward the kitchen. She smiled at me again but then turned her ear toward the hall.

“Oh,” Miss West said when she answered, a little grumpily, “hello.” A pause. “You too,” she said. And then: “She is, in fact, although she’s on her way to a dinner.” When Miss West reappeared, she said to Amanda, “It’s Rob.”

In a flash, Amanda was gone. The speed with which she hurried to answer hooked something deep in my gullet, dragging it with her. With Miss West, it registered with some embarrassment and, bless her, some sympathy.

“Ditching her at the last minute,” she said of Rob. “Not gentlemanly.” Then: “Not that it stops him.”

From where I stood, I turned to see Amanda lift the receiver from the counter, turn her back to us, and press it to her ear. At which point I noticed Miss West was standing close behind me.

“You’d think she’d learn,” she said, “with a father like hers, to pick the ones that don’t run. But the ones who run only teach their kids to chase. Cigarette?” she offered.

“No thanks,” I said.

“Or,” she muttered, catching fire, “maybe he has a ten-inch cock.”

Before I could even begin to react to this baffling statement, Amanda said, “Should we go?” She was awaiting me in the hall.

“Nice to meet you, Griffin,” Miss West said. Then, before she closed the door, said to her daughter, “No matter where your dad takes you. Get the steak.”

After we left the apartment, Amanda and I did not speak. We remained silent even after we turned north on Broadway. Amanda kept her arms crossed and her eyes to her shoes, as if by staring them down she might silence her heels against the pavement. When a passing stranger, seeing us so dressed and, inferring we were a couple, smiled, this only seemed to increase her inwardness. I was dim but no dummy. I knew that my presence deepened Amanda’s gloom, that my status as stand-in was a reminder she’d been stood up and burdened our stroll with a feeling of obligation. I realized my only currency was to provide comfort, and the only coins I had to play were changing the subject, so I asked where we were going. “To Columbia,” Amanda said. “My dad’s attending a reading there before we eat.” But then she turned quiet again, and her silence was intolerable.

“What does he do for a living?”

“He’s an English professor,” Amanda said. “At a boarding school in New Hampshire.”

“Which one?” I asked. As if I knew any.

“Brewster.”

I felt my lower lip cover my upper one as I nodded. “What’s the difference between a professor and a teacher?”

“A PhD and an ego,” Amanda said.

I waited. “What about your mom?”

“She’s a nurse. At Mount Sinai. Just a few blocks from here.” She brightened a bit. “That was sweet of you to get her roses,” she said. And then, she took my arm in both of hers. It was the charitableness of it that made it torture; it was the devotion that it so easily summoned in me that made it pleasant. And once I figured out how to walk normally and be held by her at the same time, I could nod at the passersby and enjoy that, for now, she was mine.

“Speaking of roses,” Amanda said, “she’s going to lash me with them if I don’t bring her home a doggie bag. Every time I go to dinner with my dad, that’s the rule.”

“My cousins get the belt. But only if they curse.”

“My mom prefers the back of a hairbrush.”

“My dad likes to lift me by the scruff. Like a kitten.” I demonstrated on myself, walking on tiptoes, but without moving the arm Amanda held, a marionetting that made her laugh.

“She used to lock my brother and me in the closet for hours, but that was only when we were little. No wonder he asked the judge if he could live with my father.”

We’d entered Columbia’s gates. The three long walkways were made of the same hexagonal paving stones as in Central Park. The paths were tree-lined. Black iron posts connected by black chains fenced off the greenspace. It seemed as if we were passing through a tunnel to a different world, or a city hidden within the city, for we now entered a great expanse whose buildings were of an entirely different architecture. To our right, a long rectangular building was fronted by columns whose facade was engraved with names from my seventh grade class in ancient history: Herodotus, Sophocles, Plato, Aristotle. To our left, flanked by a pair of wide flights of stairs, was a domed building in front of which a statue of an enthroned woman with open arms was surrounded by students who sat and talked in the spring-softened evening. I considered this sky, the view of which was unimpeded, its immense breadth somehow even more clearly and discretely framed by these low-slung rooftops.

Someone called out Amanda’s name. It seemed to come from everywhere. On the wide steps surrounding the statue, a man and woman stood and, while Amanda and I waited, walked toward us. Both appeared formally dressed—I said a silent word of thanks to Mom and Dad—Amanda’s father in a bow tie and blue blazer, the woman in a man’s blazer and jeans. But when they drew close, the woman accompanying Amanda’s father was revealed to be someone nearer our age. Amanda’s father so identically resembled her he may as well have been her twin.

After kissing Amanda, he introduced us to Tina Debrovner, “my most talented senior.” If Amanda, dressed and made up thus, seemed costumed as the woman she would one day become, Tina already embodied this. She wore cowboy boots and worn-in bell-bottom jeans, a silver belt buckle with a piece of turquoise at its center, and a brown silk blouse that matched her tweed blazer. Her makeup was light; her chestnut-colored hair and lashes were long; her green eyes flashed. Above her top lip, on its right side, was a mole that, for the first time in my life, conferred luster on the term beauty mark. Her style seemed fully realized; her comfort in her person spoke to everything aspirational in the word “adult.” Her hands were pressed into her blazer’s pockets, and she removed one and held it out to Amanda and then me with the total confidence of an elder and none of the condescension of a superior. Amanda’s father then reached out a hand to me and introduced himself as Dr. West. “You must be Rob,” he said.

“Griffin,” I said.

He glanced at Amanda, confused.

“Rob’s at Vassar,” she said, “visiting his sister.”

Dr. West winked at me. “Visiting co-eds is more like it.” Then, to Amanda, whom he’d clearly rocked, said to her, “But maybe they don’t call them that anymore.” He checked his watch. “Let’s head to Butler, shall we? I made a reservation.”

We started walking, Amanda and I behind Dr. West and Tina. To change the subject, I asked, “How was the reading?”

“Wonderful,” Dr. West said.

When I asked who the author was, Tina looked over her shoulder and said, “Shirley Hazzard. Do you know her? She read from her new novel.”

“The Transit of Venus,” Dr. West said. “Which, I’ll add, Tina did not like.”

She rolled her eyes. “I didn’t say I didn’t like it. I just found its style…dense.”

“More likely you’re too young to understand it.”

“I didn’t think it was beyond my comprehension. It was a scene,” she explained to Amanda and me, “when a man and a woman go on a first date together in the English countryside, and he tells her a secret.”

“That’s what happens,” Dr. West cut in, “but it isn’t what’s happening.”

“I’m getting to the subtext,” she said, and there was ample warmth in her exasperation. “What’s happening is that the man is in love with the woman, but the woman has already decided she can never love this man. That she’ll remain permanently out of his reach and he’ll be permanently reaching toward her, he’ll do anything just to catch a glimpse of her, just like…” She placed her index finger to her chin. “The planet Venus in transit. Does that,” she now said to Dr. West, “sound right?”

“It sounds perfect. Until you get to the end.”

“What I don’t buy,” Tina continued, “is that we have such complete conviction about such things from the word go.”

“That’s because at your age,” Dr. West said, “you still believe you can love things out of people. Or love them into your life.”

“It’s less a question of belief,” Tina said playfully. “I just know you’re wrong.”

“So based on the audience of a single chapter, you’re ready to dismiss the work outright?”

“Yes,” she said.

“That sounds to me like complete conviction. From the word go.”

Tina laughed warmly. “Touché.”

Dr. West turned to me and said, “Tina is a romantic, while I am a realist.”

“What’s wrong with being a romantic?” she said.

“It tends toward the neurotic.”

“Well, this neurotic finds most realists crotchety.”

“Don’t forget condescending,” Amanda said.

Dr. West, gratified, said, “What about you, Griffin? Realist or romantic?”

Overmatched, I parroted a line that my father loved to use in such situations. “I just work here,” I said.

Everyone laughed at this. Even Amanda, whom, I realized, her father had not asked and who, when she smiled appreciatively at my joke, was, I thought, trying to remain romantic, in spite of current evidence—Rob’s absence, my presence, and her mom’s ordinance—to the contrary. Which made me, I realized, feel for her. In spite of myself.

“Well,” Dr. West said, gesturing toward a building on our left, “here we are.”

From the hallway we walked onto an elevator. Dr. West pressed the topmost button, and next the doors opened onto the restaurant’s entrance, which read, in gold letters, Terrace in the Sky. Waiters in black tie hurried between tables with white napkins draped over their arms or cradled bottles of wine or balanced oval trays. A tiered dessert stand went rolling by. The hostess led us to our table at the deck’s corner. Dr. West pulled out Tina’s chair, and I did the same for Amanda. The sunset had draped its fading pink blanket above the city, and my seat had a view I’d never before enjoyed: the northwestern corner of Central Park, that Sherwood Forest it sometimes seemed Manhattan had been built to enclose, its walkways dimpled by its snow-white globes, just now beginning to shine.

Following Dr. West’s lead again, I snapped open my napkin and laid it on my lap. Dr. West, looking down his nose, seemed to somehow peruse the menu with his chin. When the waiter asked for our drink order, Dr. West said, “Ladies?” and Amanda said, “White wine spritzer, please,” and Tina said, “Sex on the Beach, please.” To Dr. West’s glance, once he, in a bit of acting, recomposed himself from Tina’s order, I replied, “You first, sir,” and with his menu still open, Dr. West said, “Martini up, please, very dry, olives.” And I said to the waiter, “Same,” at which Dr. West nodded approvingly.

“Griffin, do you know how to make the perfect martini?” he asked. “Into your shaker you add ice, then very good gin. Next you take a capful of vermouth”—and between his thumb and index finger he held up an invisible cap—“wave it over your tumbler”—he made several circles—“and then throw it over your shoulder.”

At this, the girls, who clearly understood him, laughed.

We all considered our menus. Dr. West, breaking the silence, asked, “Well, everyone, what looks good?” To which Amanda replied, “I think the filet,” and Tina said, “The duck à l’orange,” and I said, “What do you recommend?” and Dr. West said, “I’ve got my eye on the fish en papillote,” to which I, having no idea what it was, replied, “I was just looking at that myself.”

The waiter was placing our drinks on the table. Dr. West raised his glass and said, “To the romantics.” We all clinked, and when I sipped, what slid down my throat had the shininess and consistency of mercury and felt like a long snake made of ice.

Dr. West went on for a while about Shirley Hazzard. He mentioned that her husband was translating the letters of Flaubert. “Speaking of,” he said, and asked Amanda if she’d bothered to read the copy he’d sent her of Madame Bovary. She replied that she was saving it for break. “I’ll hold you to that when you come visit us at the beach,” Dr. West said. “And what about you, Griffin? What are your summer plans?”

“I’ll be working,” I said.

Dr. West said to Amanda, “I like him more than Rob already. And where, might I ask?”

“NBC,” I said.

“Griffin’s an actor,” Amanda said at her father’s piqued expression. “He does TV and movies.”

Tina, who had taken a bite of bread, covered her mouth and grabbed my wrist. “Wait, you weren’t Rudi Stein in The Bad News Bears, were you?”

“He’s in the new Alan Hornbeam film,” Amanda said. “They shot it across the street from my school.”

Tina, impressed, said, “I loved Memento Morris.”

“An actor,” Dr. West said. “What school?” When I told him I went to Boyd Prep, he said, “No, I mean your formal training. Like the Method?”

I had no idea what that was.

“It’s all baloney, of course,” he said, waving his hand before his face. “Pasteurized. Self-obsessed. Quintessentially American.”

Tina looked at me gravely and then at Dr. West as if to say, Here we go again.

“The British gave us Shakespeare and negative capability. America gave us autobiographical motivational narcissism,” he said.

“Griffin’s appearing in As You Like It,” Amanda offered. “At his school. I’m going to see it next weekend.”

“And who do you play?” Dr. West asked.

“Charles the wrestler,” I said.

“Wonderful,” he said. “And what do you make of it?”

I looked at Amanda, who looked at her father. “I’m not sure I understand,” I said.

“Of what Shakespeare is trying to say.”

“I don’t…We don’t really talk about it like that.”

“How about this: What do you think of your character? What do you see as his function in the drama? Certainly you’d have to have some idea of that in order to do your job.”

“Well, he sort of explains everything,” I said. “Like in Freytag’s Pyramid—”

“Yes, but what motifs does he introduce? What plot levers does he pull?”

“I’m only in the first act,” I said.

In what remains one of the most intimate gestures I have ever seen, Dr. West pointed his remaining speared olive at Tina, and she, without hesitation, plucked it from the toothpick with her teeth.

“It sounds to me,” he said, “as if you don’t even have a rudimentary grasp of the play’s rhetorical architecture, let alone its plot. Which is sad, when you think about it, at least”—he starfished his hand against his chest—“to me. I mean, here you are, memorizing important literature, the most important literature there is, really, but you have no context for it whatsoever. You’ve got your part down cold, as it were, but no idea of the whole. You come onstage and say your lines, and then off you go. Like a dolphin miming human speech.”

“Daddy,” Amanda said.

“No,” Dr. West said, “this is crucial.” And then to me: “When you perform next week, maybe keep in mind that it’s Charles who not only provides essential exposition to the audience but also supercharges the word ‘fall’ with meaning throughout the entire play. Whether it’s to suffer a fall, as in lose one’s stature—which Charles literally will do when Orlando stuns him with his wrestling victory—or fall in love, as Orlando and Rosalind do so suddenly and completely before the match transpires. And as Touchstone and Audrey will upon their arrival in the forest of Arden. And Phoebe with Ganymede. True, I’ve often thought it’s nearly a deus ex machina that Duke Frederick falls in love with God toward the play’s end, his religious conversion seems so entirely out of character. And, of course, there’s the pun fall on one’s back, which introduces the play’s anxiety about everything from cuckoldry to premarital sex. And falling out of love, which stands in for the play’s greatest anxiety—one which all the characters suffer—which is the passage of time. Time, which either ruins or changes everything—even a love well begun. And which, as Jaques notes in his ‘seven ages’ speech, none escape—its passage, I mean. But we are all always wrestling with that one.”

Dr. West raised his eyebrows and smiled. The waiter appeared with the wine bottle. He went through his elaborate ritual. As he filled the second glass and tipped the bottle toward the third, Amanda held her stem with one hand. With her other, she took mine beneath the tablecloth and squeezed my palm comfortingly. While I, thoroughly enjoying her secret attention, smoldered with determination. Because I was officially sick and tired of not being in the know.

Not that this spurred me to change. At least, not in the way one might think. Later, back at Amanda’s apartment, her mother gone for the evening, I soon forgot Dr. West’s dressing down, having, as I did, Amanda to myself. Between her bedroom’s twin beds there ran a strip of blue painter’s tape, her brother’s unoccupied bed, by her mother’s decree, remaining right where it was, and the room divided evenly, Amanda explained, should he ever drop in for a visit or decide, one day, to finally come to his senses (these her mother’s words) and move back in with them. Between the headboards there was also a small table with a record player atop it and sleeves of forty-fives and albums in the cubby below. While we talked, we listened to the Commodores’ “Three Times a Lady,” Earth, Wind, and Fire’s “September,” and John Lennon’s “Watching the Wheels.” At the far end of the bedroom was a bookcase, and on its shelves Amanda had a couple of pictures. One was of her father, standing before a body of water, somewhere coastal, a red house also in the background, holding both his children’s hands. Amanda was maybe four years old in the photograph, towheaded, wearing a white dress with cornflower trim; her brother, Eric, a couple of years older, in a jacket and bow tie; and Dr. West, in what for all intents and purposes was the same outfit as tonight, with the exception of sunglasses, which gave him a more forbidding, inscrutable appearance, perhaps also because he wasn’t smiling. Her brother, Amanda remarked, was, in temperament, exactly like her mother, blunt at his worst, honest to a fault at his best. She had no idea how father and son tolerated each other, seeing as her mother and father could barely get through a conversation without fighting. When I asked her if she was more like her father, she said no, she was more like her grandmother, of whom there was also a picture, whose frame she handed to me and then joined me on her brother’s bed to regard (in the reflection of its tiny square of glass we were briefly framed), this of a woman on a deep-sea fishing boat, harnessed in the fighting chair, rod bent but secured in its gimbal, clearly some immense creature on the line. She was wearing a long skirt and blouse and fine shoes, as if she were headed to a summer cocktail party at a country club, shouting, happily, at the sport of it all, and she looked—this was the first thought that came to my mind—like Grace Kelly might on such an expedition: drop-dead gorgeous and perfectly overdressed. More precisely speaking, there was a clear lineage, appearance-wise, from grandmother to father to Amanda. Apparently, her grandmother had been a very wealthy woman, a socialite and art lover. If I’d grown up at the Museum of Natural History with my mom, then Amanda had spent hers wandering the Whitney and Guggenheim with her grandmother. She had apparently squandered her fortune on four marriages (the photo was taken on the boat of her second husband, a Cuban hotelier), and when I asked Amanda why she was more like her, since serial monogamy and heartbreak didn’t seem like something to which one might intentionally aspire, she finally answered her father’s question: “Because I’m a romantic too.” Amanda replaced these photos on their shelves and continued to DJ (“Get Down Tonight,” “Night Fever,” “Give Me the Night”), and while we, like an old couple, lay in our separate beds, I could not help considering the photos further—they seemed traced in light to me, they branded my memory such that I was aware, in that moment, that they’d leave a mark, this a minor mutant ability I was just becoming aware of then and have since learned to trust, when an object or person seems limned in vividness, close to a camera’s flash, an afterimage I know I’ll contemplate later. It was only years hence that I came to consider those two photographs as the poles of Amanda’s personality—and that I was here, in her life, to supply her with a measure of safety: I was harness and fighting chair while she angled for the elusive and mostly absent prize to thereby heal the suppurating wound of her departed father; that she, having learned that this was how the sport of love was played, would set that hook deep, as she’d done with me, as her grandmother had in that photo, but that she was determined to land that fish this time, and I could be damn well sure she’d stay rich to boot.

Not that I thought any of this at the time. I still believed I had an angler’s chance. Which is why here is a good time to mention that Rob called just as Amanda placed “Escape (The Piña Colada Song)” on the turntable. “Hi!” she said, so ringingly it was clear all was immediately forgiven, even before he apologized for standing her up at dinner and explained he’d come home from Vassar early to make it up to her, could they get together tonight? And to my heartbreak I watched Amanda, beside herself with excitement, freshen her makeup in her bedroom’s mirror and then offer to share a cab with me downtown (Rob was paying), dropping me off on my street before continuing on to Studio 54. I didn’t bother to mention to Amanda—the both of us, by that point, having had enough of her dad for the evening—that out the cab’s window, I spotted Dr. West and Tina walking down Broadway, her arm slipped through his, something that, back then, didn’t strike me as especially odd, so well groomed was I by that time, so desensitized, up and down the food chain, to such behavior.

My own dad managed to come to opening night of As You Like It the following week, along with Oren and Mom. Amanda, who sat separately from them, was also in attendance. I spied them from the tiny theater’s single wing just before curtain: my family seated front row center, Amanda in the back, alone. Suddenly I was something I never was in front of any camera: nervous. My scene with Duke Frederick went well, although I had to make it a point not to look at Oren, who was crossing his eyes at me. Before my bout with Orlando, I strode onstage to the audience’s applause, milking the moment with a deep bow. I removed my tunic, as did scrawny Orlando. Suddenly, with Amanda and my father present, I was also something I never was before any camera: self-conscious. Orlando and I clasped (Damiano had asked me to do the fight’s choreography), I shrugged his neck and chin under my forearm and, with my other upraised, triumphantly walked him about the stage, which got a laugh and elicited from Amanda the same beaming expression as when I’d first performed for her. When Orlando wriggled free, he ducked between my legs and then cuffed the back of my head—“O excellent young man!” shouted Rosalind—in response to which I charged him. He got me in a headlock and hip-tossed me to the ground, where I landed with a great bang, right in front of my father’s seat. Orlando was victorious; I was “unconscious.” Before a pair of Duke Frederick’s men dragged me offstage by my wrists, I peeked at my father. He was frowning and, whether he was aware my eyes were on him, slowly shook his head in disapproval. Why, he seemed to be saying, are you wasting your time doing this bit part?

After curtain calls, there was a reception in the front hallway. Having never really been a member of the cast, I stood on the perimeter of the crowd. When my parents found me, Oren, with a plate of cheese and grapes, complained that if he’d known I was only in the show’s first act he wouldn’t have sat through the entire play. Dad, nodding at the passersby, spoke in his big voice, leaning into his truisms: “It’s a very, very important comedy,” he said. I was, he also noted, clearly the only pro in the troupe, though he had to grant the actors playing Rosalind and Orlando had “terrific chemistry,” the girl who played Celia was “quite lovely, in fact,” and then Amanda appeared.

She wore a sleeveless blue dress and high heels, as if this was opening night on Broadway, and she congratulated me and then handed me a present: “I made you a banana bread,” she said. It was wrapped in tinfoil and plastic and had a ribbon tied around it. I introduced her to my family, and Mom said, “You must be the young lady Griffin had dinner with last week,” and from that point forward, something remarkable happened: my father went quiet. There was some small talk, none that I made, or Dad either—even Oren gave Amanda all his attention as she and Mom chatted. I occasionally spied my father looking at Amanda with an expression that was, at the time, entirely unrecognizable to me. I might have called it approving, but there was something bittersweet about it, a wistfulness that was oddly reverential. It was so uncommon for him to be this watchful, and in that interval, I also noticed him watching me watch Amanda, since it was my chance to do so, secretly. At these moments, when we caught each other’s eye, he smiled at me, warmly—the closest I could come to naming what his face conveyed was pride. But even that wasn’t quite correct. There attended this attention a kind of generosity. It was a Thursday, a school night. Mom asked Amanda where she lived and, when Amanda told her, Mom said they’d driven the car uptown. “Shel,” she suggested, “why don’t you and Griffin take Amanda home, and Oren and I will take a cab.”

When Oren asked, “Why wouldn’t we all just drive together?” Mom replied, “Because I said so.” She told Amanda it was lovely to meet her and then led my brother out the door.

This quiet that had settled over my father persisted during the drive. Amanda and I sat in the back seat and talked about the play. I caught Dad glancing at me in the rearview mirror now and again. He nodded, pleased.

“This is my building,” Amanda said to my father.

Dad said to me, “Why don’t you walk your friend to her door?”

Amanda said to him, “That’s okay, we’re right here.”

Dad said, “I insist. Griffin, see the young lady upstairs. Amanda, it was lovely to meet you.”

Inside, we boarded the elevator. Two feelings struggled for dominance. The first being relief that Amanda and I were finally alone. The second being the conviction that I’d have done a whole semester of performances just to have a moment like this. I smiled, warmed at these thoughts. I glanced at Amanda, who was smiling at the indicator lights as they brightened and then turned to smile at me. Here, once more, I heard the clarion call to action but did not obey. And then the lights went out and the car jerked to a halt.

“Oh no,” Amanda said in the pitch-darkness, although she did not sound scared. “This happens sometimes.”

“What do you do?”

“We wait,” she said. “It’s usually only for a minute. Though I was once stuck in here for three hours.”

We stood in the blackness. Amanda’s dress crinkled, as if it were alive.

“What would we do for three hours?” I asked. When my question’s suggestiveness occurred to me, I was glad she couldn’t see me blush.

“We could talk,” she said.

“We could.”

“It doesn’t seem to me like we ever struggle for things to talk about.”

I felt the same way.

“Sometimes,” she continued, “I think that all the conversations you and I will ever have will be in places like this. Buses, elevators. The apartment where I babysit. My room. If that was for the rest of our lives, how much time would that add up to?” She took my hand; hers was damp. And the tenderness I felt toward her surpassed my lovesickness, because I could tell that she, too, was a bit scared. “Do you ever think about that? How much time you’ll spend doing dishes? Or that you’ll really have with someone, like your brother or sister, if you do the math?”

The lights came on. We blinked at the brightness. The door opened. She said, “You’re so talented,” and kissed my cheek, which was partly a command to stay, and stepped off the car. Then she turned to wave goodbye and the door closed.

The elevator sank. I thought about what Amanda’s mother had said the previous week, about picking the ones who don’t run and how Amanda had been taught that love was a chase. Shouldn’t love be a swimming with, like fish in a school, as opposed to a swimming after? And if I wasn’t chasing, what was I doing?

That these questions had no answers made me miserable.

In the car, once I’d taken my seat in the back, Dad said to me, very gently, “Why don’t you come sit up front?”

When I came around and took the seat next to him, he paused to regard me before shifting into gear. I sat slumped against the door, arms crossed, with my temple pressed to the window. He eased down the street, stopping again at the light. We stared at Saint John the Divine, its facade filling the entire windshield. It was late and the streets were empty. We could have parked here if we wished.

“Beautiful building,” Dad said, and leaned forward, over the steering wheel, to look up at the cathedral. When I remained silent, he said, “You want to tell me about her.”

I gave him a complete account of the past several weeks. They had seemed like years, and when I mentioned this, he nodded knowingly. By now he had backed into what, at an earlier hour, might not be considered a parking space, but did not kill the motor. He listened with the same respectful silence as earlier, sometimes lightly laughing with me, other times, with his elbow at rest on the door, rubbing his finger over his lips, as if he were thinking thoughts entirely private and tangential to mine. He had questions, now and again. I felt unburdened answering everything he asked, but when I concluded none of it mattered, it was all hopeless, he said, in what at the time felt like a such a complete rebuke of Dr. West I wanted to hug him, “You can’t ever predict how a person’s feelings might change over time.”

We considered the cathedral again.

“When were you first in love?” I asked.

Whatever my father recalled, whatever made him shake his head, there was no acting in it.

He shifted the car into gear.

“Let’s take a drive,” he said.