Video Killed the Radio Star

When I recall how I spent that August, it is no surprise to me that I took refuge in the most surprising place of all, one I had never bothered to make my own over the past four summers but now went so far as to decorate: my dressing room. It was nearly as big as the bedroom Oren and I shared. It too had a bunk bed, the top and bottom with oval-shaped entrances that gave them a cozy, alcove feel. Parallel to this, and like our apartment’s dining room, there ran a wall-length set of mirrors, but with vanity bulbs. Beneath these, like my closet study, and also stretching its length, was a floating desk. Beneath this, a minifridge, stocked for guests (I had only two that month), with a whole assortment of sodas, snacks, and skim milk for my cereals, the boxes arrayed on the desk above. I had my own bathroom with a shower. A TV, suspended in the corner, above the fridge, with access to the major networks, and a live feed from The Nuclear Family’s taping sessions that I sometimes liked to watch, sound off. The best part: no windows. Along with my bunk bed, it gave the room a submarine feel, which I relished.

It also had air-conditioning, which was a relief from August’s unrelenting, kiln-hot temperatures, an all-out assault comprising sunlight that reflected off car windows so brightly I had to squint and heat that radiated from the tarred cracks so softened in places it stuck to the soles of my sneakers. This swelter was coupled with humidity so high it made any breeze feel more like a blast from a hand dryer and, rather than eradicate the city’s smells, only intensified them. Traffic and the uncurbed dog shit and the refuse in the wire trash bins through which this fruited air passed. The stink rising from the subway’s grates after mixing with the tea-brown puddles that never seemed to evaporate along the tracks—a steeped, rusty mixture of rail soot and grime that the cars’ blue flash ionized into a gas and, taken together, only existed at summer’s end in New York, when the season seemed endless; and relief, which fall promised, also meant the beginning of school.

“If I had a place like this,” Oren said, “I’d never leave.”

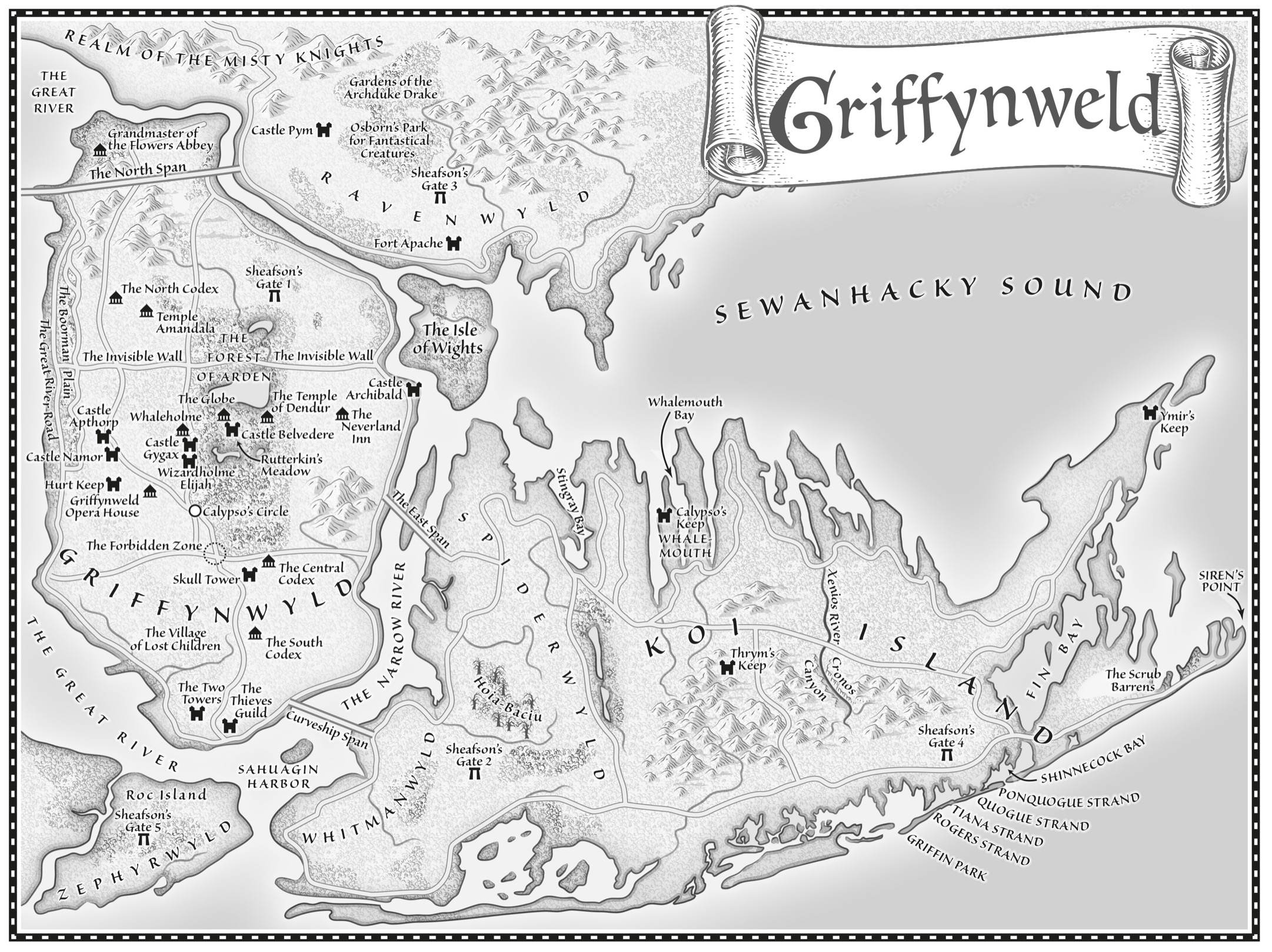

He was one of my dressing room visitors. He did not come by often—maybe three times that month. Things had not been the same between us since he told me how I’d deserted him the night of the fire. If my recollections, which were so vivid, could be so suddenly altered, who was I? What had happened? I apologized to Oren on his first visit. I confessed that no matter how hard I tried I couldn’t remember doing what he’d accused me of, and in response he said, with some exhaustion, something so wise it was on par with one of Elliott’s aphorisms: “Let’s chalk it up to childhood.” It was for him I’d stocked the room with food; when he’d showed up that first time, he mentioned he was hungry, but when I offered to take him to the commissary, he declined, he had to get back to work—which I incorrectly assumed was still at Popeyes. After that, I was sure to have his favorites: Streit’s matzo, which he liked to eat with margarine, as well as Flower brand Moroccan sardines, the ones in tomato sauce, plus Oscar Mayer bologna—my most famous commercial—with Kraft singles, which Oren rolled into tubes. He’d been living with Matt, he told me when I asked, at Matt’s father’s place in the Beresford. It was great, he explained. He was a record producer and spent his weekdays in Los Angeles and Nashville, so they had the run of the apartment. “Speaking of,” Oren said, sounding like Dad, “I love what you’ve done with the place.” He meant the maps of dungeons and castles for Griffynweld I’d taped to my walls, the monsters I’d drawn (a mind flayer, a manticore, a harpy, a golem, a griffin), my manuals and dice stacked next to my unread pile of summer reading books. I urged him not to look too closely. It would spoil the surprise. We’d be playing together in September, when Dad finally got home.

“You mean ‘if,’ ” Oren said.

I didn’t want to think about it.

“You speak to him?” he asked.

“He calls me here sometimes, before curtain.”

“Where is he now?”

“D.C.”

“What about Mom?”

The Monday morning after my weekend at Amanda’s, before I’d headed to work, Mom had called me into her room. A mostly packed suitcase lay on her bed. “I’m taking the train this afternoon to Virginia, to spend some time with my parents,” she explained as she folded some remaining clothes. “Most of my ladies are on holiday anyway,” she said, referring to her clients. Dad’s show had just begun previews at the Kennedy Center, so I asked Mom if she was going there to be nearer to him. She shook her head. “I’m going there to be nearer to myself,” she said, clicking the suitcase’s clasps. I understood what she meant and I didn’t. She beat me to my next question.

“The Shahs have agreed to let you stay with them while I’m away.”

I blinked at this several times; it was all the reaction I could muster. “But they live in Great Neck.”

“They commute,” Mom said.

“What about Oren?”

“He’s staying at Matt’s.”

“How long will you be gone?”

“A week,” Mom said. “Maybe longer.”

“Are you and Dad getting a divorce?”

“We haven’t talked about it.”

“Does he know you’re leaving?”

“We haven’t talked about that either.”

“I don’t understand.”

“You will when you get older.”

“Why do adults always say that?” I asked. “It makes me never want to grow up.”

“That’s fair,” Mom said.

“It’s not.”

“No,” Mom said, “none of this is fair.”

She reached her arms out to me and we hugged. I had grown much taller than her, though she only seemed smaller when we weren’t touching. Her temple rested on my chest. She was the most physical with me when she was in pain.

“Naomi is very fond of you,” Mom said. “You’ll be in good hands.”

Naomi’s hands. I slept in the Shahs’ guest room, the only bedroom on their house’s first floor. Over those next several weeks, after everyone had gone to sleep, after Naomi slipped through my door and padded across the carpet, she would grope my blanket in the pitch-dark, patting down my outline like a child feeling for a parent after a bad dream. Her slip’s sheer fabric, once she’d tented the sheets above us, sometimes generated static electricity, and her body, so blued by dark as to be invisible, seemed briefly strung with heat lightning, which crackled. Her laughter, now that she lay atop me, was throaty, wicked, pleased. She liked to clasp my chin between her thumb and index finger when she began to kiss me, as if to assert that I was hers now, that there was no getting away, and in those initial weeks, I did not want to. I wanted to exercise my new powers, spread my wings. I thought about the first thing Kepplemen had taught us about wrestling: Where the head goes, the body will follow. So I moved Naomi around, I reversed our positions. I flipped her over to claw the back of her neck. She loved when I did this, she was encouraging as we proceeded. She gave me directions, she spoke as if she were teaching me to drive: go slow, speed up, go easy, go fast. It felt wicked, before and during—this velocity—though afterward it made me terribly sad.

The Shahs lived in the Saddle Rock neighborhood of Great Neck, just a few blocks from Little Neck Bay. Their home—two stories tall and designed like a giant H—was on Melville Lane, between Byron and Shelley, a cosmic joke I wouldn’t understand for years. Their foyer, its floor laid with great slabs of black-and-white marble, was dominated by a wide set of twin stairs whose strands, after ascending, met again at a long hallway—the letter’s crossbar. If you made a left, you arrived at the family wing. On the top of this stem, the west-facing side, was the Shahs’ master bedroom, which I visited only once during my stay.

Danny and Jackie, on the first afternoon after I arrived, gave me the tour. The master, which I’d been in that past winter but had not seen in the light (I’d walked through it in a daze, after my wrestling tournament, on the night I was concussed, before Naomi led me to the shower), was made bright by three large windows, which the Shahs’ California king waterbed faced, this second-floor height affording a view, over their yard’s high hedges, of Little Neck Bay. Above the headboard was a recessed section of wall, top-lit, its lower edge serving as a shelf. There were several books here: a pair of leather-bound copies of the Quran as well as a multivolume set of the Hadith, whose gilded spines, taken together, formed embossed letters in Arabic. Above these volumes hung a calligraphic painting, the symbol of Allah—I recognized all these from my days at Al and Neal’s apartment—beneath which there rested an ancient saber in an ornamented scabbard, balanced on the alabaster cast of a woman’s long-fingered hand. “We’re not allowed to touch the sword,” Danny said, as if she’d read my mind.

She led us to her room at the stem’s middle. It was decorated, paint to linens, in various shades of pink, every item exhibiting the same sheer femininity as a dancer’s tutu. A framed Degas, one of his soft-focus, seen-from-the-wings dancers, stood above the dresser. Her large window’s sill was arrayed with a menagerie of Baby Alive dolls. A collage of Fashion Plates designs, all of which were of women in variously patterned leg warmers, covered the bulletin board above her desk. Her bedroom was connected to her sister’s bedroom by what she called “our Jackie and Jill bathroom,” a phrase she’d clearly heard from her father, since her tone had the same cutesy inflection he liked to use with them.

Jackie’s room (“Follow me, please,” she said, taking over the tour) was for the most part the twin of her sister’s—the same color scheme, the same puffy pink polka-dotted bedspread. Above her dresser were three sets of women’s pointe shoes, one toe of each autographed: Darci Kistler, Kyra Nichols, and—in a fine hand that I’d seen in the margins of The Age of Innocence and The House of Mirth as I searched for Dad’s stash of cash—Lily Hurt, my mother. A pair of framed posters hung above Jackie’s headboard, both of Baryshnikov. In the first, that famous shot by Max Waldman, Misha is shirtless, his torso chiseled, his foot extended well above his ear—développé en l’air, as Mom would say—the picture snapped mid-leap, his right hand touching his pointed toe, the other arm outstretched while his head is flung back. In the second, by Richard Avedon, he is naked and so stirringly virile that when Jackie caught my eye after staring at it, I realized for the first time how closely she resembled her mother.

My room, downstairs on the H’s opposite stem, was somewhere between a maid’s room and a study. It had its own bathroom and a window that faced the driveway. Two full beds were arranged against this same wall, and between them was a small desk. Above it, a quartet of individually framed photographs of trucks decorated with rainbow-bright designs and friezes—Pakistani folk art, I would later learn, that adorns its country’s buses. There was a more formal guest room upstairs, above the garage, but I quickly came to understand my room had been picked by Naomi because it was the diagonally farthest from the master. You had to first pass through the dining room, whose collection of china sat on a pair of decorative shelves and tinkled loudly when you walked through it. From the dining room, a swinging door opened onto the kitchen—this in the middle of the stem—which, if you made a right once you’d passed through it, led to what Jackie called the Blue Room, because its walls were painted a deep, lacquered navy: a sitting room of sorts, formal and clearly never used, with the door to my room opening onto it. If you turned around and continued through the kitchen, again headed toward the house’s bay side, you stepped down into a glass-enclosed sunroom with a tulip table at its center surrounded by four chairs. The slate floors were outfitted with radiant heating—an unimaginable technological luxury back then—which the Shahs kept turned to high during the summer because they cranked their air-conditioner morning to night.

The sunroom looked out on the well-manicured backyard and a water feature, a large koi pond, whose filter made a pleasant burble. My only chore for those three weeks that I lived with them was to feed these fish in the evening. They ate pellets that smelled like dried cat food, and when I so much as passed my palm above their pool, the fish coalesced into a single being, a mythological creature, many-mouthed, and their lips, when I lowered my cupped hand amid their massed bodies, were mobile and delicate, sucking and kissing away their meal. Their tenderness always brought a smile to my face, as it did to Naomi’s, whom I often spied watching me from the living room’s floor-to-ceiling windows—this room behind the staircase, where the TV lived, and where the family spent most of its time together. She’d check over her shoulder to see if Sam was nearby, and if he wasn’t paying attention—he, in profile, was usually glued to the news—she gave me a secret wave.

On the mornings when I was shooting and had to be in the city early, it was Sam who drove me. “Pick,” he’d say, gesturing toward the Bentley and the Ferrari as the garage door clattered open. I always chose the Ferrari—the 365 GT, that gorgeous bullet of a vehicle and one I became very familiar with during those several weeks. Sam relished this crack-of-dawn opportunity to “peel,” as he liked to say (it was also the word on his custom license plate). It offered him the excuse to leave for work even earlier than he would normally and thereby enjoy what he called his “freshest hours,” when he was the only person in the office and could, as he liked to brag, “get more done before nine a.m. than anyone else before lunch.” He said this often, clearly pleased with what he considered such a felicitously phrased witticism. He always laughed, whether I did or not. I, a decent mimic, would practice my impression of it if I wanted Naomi to give me some distance, to cool her desire, its sound being so anti-libidinous to her because of its familiarity. It had a lower, more masculine register; it was a dash of spit mixed with a scoop of gravel, and its four notes revved louder with each detonation, injected, as it was, with self-satisfaction: Hew, went Sam, hew hew hew.

The hour’s lighter traffic gave him license to speed, and we touched some Autobahn numbers on those morning commutes, which made me laugh as one does on roller coasters or during near-death experiences. And yet my response was equal parts giddiness, because Sam was so clearly expert at the wheel. He saw seams in the Long Island Expressway’s ever-shifting lanes that conferred the sense that we were on an invisible, zigzagging lane, newly paved just for us. During these drives, as I chuckled instead of screamed, I saw—as I had during my weekend with Amanda, and now, during my night visits with Naomi—that part of the nature of my character was to blur into background, to camouflage myself, to cuttlefish in order to hide. And in my newfound state, I found it repulsive, I wished to molt it from my person. I arrived at 30 Rock with my pulse thready and heart pounding from the ride; I slipped toward sleep, after Naomi left my bed late that night, in the exact same state; in both instances, I suffered self-loathing. I was riding two waves, abdicating agency because of circumstance, and I decided I needed to change this about myself as soon as possible. Or at least talk to Elliott about it upon his return from vacation. Assuming, of course, I didn’t get myself murdered by Sam in the meantime.

During these high-octane performances of Sam’s—which was exactly what they were—he enjoyed talking about the Ferrari’s handling. Its hood was disproportionately lengthy to accommodate its massive V12; its fender was wedge-shaped, with hideaway headlights that, when collapsed, maintained its sharp lines. The Ferrari’s appearance was more sedan than a sportscar, but there was something unmistakably ferocious about its makeup, something mako-like in its slipstreaming capacity to torpedo down the road. The interior was James Bond classy, its walnut dash full of unmarked black switches, one of which, on my most paranoid days, I feared Sam might flip and eject me through the roof. “Listen,” Sam said as he drove, and cupped a hand to his ear, “to the induction noise. You feel that steady rev? That is the V12’s effortlessness. Here we are in third gear, and you wouldn’t know we were about to touch ninety miles an hour. Because that is where the car wants to cruise. It makes you forget speed limits. It makes you want to break the law.”

I knew Sam was showing off. I also knew he was thrilled to have another man around. Given that he lived in a house full of women, I was important to him. My audience, given that he was his company’s owner and boss, also made me, in his estimation, less of a yes man than a test case. I also knew I possessed qualities that he did not and was envious of, jacked up as I was from my summer workouts, my body pheromone-flooded, my dalliances with his wife signaling, precognitively, my alpha status. It was to my great surprise, during these drives, that I discovered how insecure he was about what he perceived to be his deficits. That in spite of his money, clothes, and cars, he suspected he was…uncool. What he wanted, then, was my approval.

So he overcompensated. That first week, during what must have been only our second drive together, a terrible accident near Flushing Meadows forced us to detour onto Grand Central Parkway and to then swing north to the Triborough Bridge. When we crossed the Harlem River, we found traffic snarled on the FDR—a ripple effect of all the rerouted volume. “Shortcut,” Sam said, and yanked us onto the 116th Street exit in East Harlem, seemingly deserted at this early hour. At the very first red light, we were beset on both sides by squeegee men. “No, no!” Sam shouted, and knuckled his window several times. “No, thank you!” But they’d already soaped down the windshield and raised the wipers. Through the suds, the now-green light dripped like wet paint until it was S’d back into its solid state by the squeegees’ rubber. “Motherfucker,” Sam said, reaching over my knees to open the glove box, revealing the silver bulk of a .44 Magnum, a weapon I knew from the Dirty Harry movies. He threw open the car door and stepped out into the lane. He brandished the pistol and then shouted, “I said, ‘No, thank you!’ ” as the two men, sprinting, shrank into the distance. Sam watched them for a moment, then pincered the abandoned sponge from the hood and dropped it onto the pavement. He kicked the tipped-over bucket out of the Ferrari’s path and got back in the car.

“These people,” Sam said, replacing the pistol in the glove box, “are ruining this country.” He dropped the car into first and gunned the engine. “Nixon at least was willing to say it. Reagan, not so much.”

Our current president loomed large during my first week with the Shahs. When Naomi and I arrived home that Thursday evening with Danny and Jackie in tow, Sam greeted us at the front door holding a sweating magnum of Dom Pérignon. “Hurry,” he said, “or else you’ll miss it.” He led us to the living room and, while he fiddled with the bottle’s cage, indicated we should watch the television. There was Reagan, seated at table outside his home in Rancho del Cielo. Beneath a denim jacket, he wore a white shirt with a western collar, jeans, of course, and cowboy boots. It was so misty you could barely make out the press corps gathered around him. Whether it’s the fog itself or the fidelity of the camera, everything looks like a dream, the vapors are so thick there is a soft-focus quality to every image. President Reagan, said the anchor, offered remarks before signing the Kemp-Roth legislation into law.

“I can’t speak too highly of the leadership, the Republican leadership in the Congress, and those Democrats who so courageously joined in and made both of these truly bipartisan programs. But I think in reality the real credit goes to the people of the United States, who finally made it plain that they wanted a change and made it clear in Congress and spoke with a more authoritative voice than some of the special interest groups that they wanted these changes in government. This represents a hundred and thirty billion dollars in savings over the next three years. This represents seven hundred and fifty billion dollars in tax cuts over the next five years. And this is only the beginning.”

With great fanfare, Sam produced the sword that usually rested above his bed, ran its blade up and down the bottle’s neck three times, and then, with a quick stroke, sabered it open. A great pop followed. The girls leaped and clapped. Naomi shook her head at me. Sam filled the flutes and handed them out. After raising his glass, he shouted, “To getting rich!”

Jackie said, “I thought we were already rich, Daddy.”

“Well,” Sam said, “now we’re richer.”

And then he laughed that rich man’s laugh of his. A sound that affirmed what Elliott would say to me later that year: judge people not by how they lose, but how they win.

In the evenings, it was Naomi who almost always drove us, but only on rare occasions immediately. She would pick me up in front of Radio City Music Hall and then make straight for the Dead Street. Though once, in the back seat, after she had buttoned her blouse, she startled me by saying, with a pain in her voice that was close to anger, “It really bothers me that you never ask me to come see you at work!” I was stunned by this. The thought hadn’t even occurred to me. And when she began to cry, I found I was frightened by this display of emotion.

“I’m sorry,” I said.

“I’m sorry,” she said, and wiped her eyes, “I just want us to be more than just”—and she swept her hand in front of her—“this.”

I didn’t know what I wanted, but I knew exactly what was being asked of me. So I kissed her gently, then firmly, repeatedly, pecking at her till she started smiling; I tickled her until she stopped crying, till she began to giggle; and after she told me, “Stop,” and blew her nose, I promised to make it up to her, sweetly. “Come to the studio tomorrow,” I said, “after lunch.”

I met her in the lobby. I was in my Peter Proton costume—suspenders, pocket protector, capri pants, Einstein wig, gigantic glasses—which Naomi thought was hilarious. I even greeted her in his nerdy voice. “Look at you,” she said, “all in character and everything.” I walked her past Sert’s American Progress mural and his smaller frescoes, pointing out the figure I liked best—the titan carrying the gigantic branch, straddling the ceiling columns, with the bomber squadrons in the background, sailing through the clouds—as if I owned the paintings, as if this were my living room. When we approached the security guard’s podium, before the elevator bank, I showed him my NBC identification card, which Naomi asked to see as well, examining it over my shoulder while we waited for the next car, clasping her hands in front of her because, I could tell, she was so nervous and excited. “Look at you,” she said again, and knocked her shoulder to mine, “all official and professional.” I gave her the entire tour of 8H, starting with a view of the soundstage from the audience’s balcony seats so she could appreciate the space’s vastness. We had to speak very quietly because they were taping—a scene in which our archvillainess, Lady Lava, has trapped my parents beneath her volcano, binding them back-to-back and suspending them above a pool of magma, using them as bait to lure me into her trap. Fog machines pumped white smoke from the pit. “Look at all the wires and stuff hanging from the ceiling,” Naomi whispered. “How do they know which plug is to which, you wonder?” I explained to her that the red light flashing atop each video camera meant that it was the feed the director had cut to, that the trickiest part of the boom operator’s job was to get the microphone close enough to the actors to pick up their voices while not dipping it into the shot. When Tom called “cut” over the speaker, I led Naomi down the hallway to hair and makeup, where Nicole and Freddie were sitting in their respective high chairs, smoking and reading the newspapers.

“Wow,” Naomi said to Freddie, “salon care for this kid every day. If I had you around, maybe I could get mine under control.”

“Probably not,” Freddie said, and smiled, which made Naomi laugh, because she didn’t know him.

I took her to costume, showed her the Coneheads suits, the Killer Bees outfits, Belushi’s Samurai hotel kimono, the turquoise tuxedo jacket Bill Murray wore as Nick the Lounge Singer. Naomi fingered the outfits, pulled at an unraveling thread in Father Guido Sarducci’s habit, and tsk-tsked. “That show’s a little too irreverent and racy, if you want my opinion,” she said.

We proceeded to the control room. “Look at this place,” Naomi gasped, surveying all the buttons atop the panels lit up like Christmas lights and the array of screens. “Tom’s the director,” I said, and pointed him out to Naomi, “the bearded guy in the Hawaiian shirt.” He was seated before the monitor wall. Jeff, the video-switcher tech, was to his right. When Tom snapped his fingers and called out, “Camera three, and one, and three, and two,” I explained how they were cutting between units, that on the three left-hand monitors you could see the cameras’ individual feeds and on the fourth screen the scene in continuity.

“And who are they?” Naomi asked, indicating the pair at the adjacent console.

“That’s Julie and Jim,” I said, “the lighting technician and lighting board operator.”

“And what about the girl,” Naomi asked, “sitting next to the director?”

“Oh,” I said. “That’s the script assistant.” And as if I were possessed by my father, my eye twitched. “That’s Liz.”

“Huh,” said Naomi, and crossed her arms.

Liz looked over her shoulder at me. She smiled her toothy smile and waved. I told Naomi she could watch us shoot my scene from here or the soundstage.

“Doesn’t matter to me,” she replied, a little coolly.

I decided to take her to my dressing room. Once there, I turned up the TV’s volume and had her sit in my chair.

“Maybe I should get back to the office,” she said.

I took a deep breath. “I’d like it if you stayed,” I said.

“I don’t know what I’m gonna do, we’ll see,” she said, miffed.

I marched to the set. The scene took maybe a half hour to shoot. The entire time, it was as if I could see Naomi’s face in each camera’s lens. To my relief, she hadn’t left; to my annoyance, she was still there, because it was as if she were my girlfriend.

“Do I get to meet your costars?” she asked, and so I took her to the soundstage and introduced her to Natalie Forrest, who played Lava Girl, and of course Andy Axelrod, who, after exchanging niceties with Naomi, after singing my praises to the catwalks, caught my eye, nodded toward my guest, and, to my horror, gave me the thumbs-up.

Walking Naomi out, she stopped me. “Ugh, I forgot my purse in your dressing room.” It was sitting atop my desk, among a scattering of maps and hand-copied tables, next to several pewter figurines that stood in for my friends and for the monsters that surrounded them. The ceiling monitor beamed the empty set of Lava Girl’s lair. Naomi said, “Close the door,” and took a seat on my bed, bouncing a couple of times on the mattress to test its firmness. Then she called me over to her.

“I loved watching you perform,” she said, and pulled me close, locking her hands behind my legs. “You’ve got great comic timing.”

The compliment made me ashamed. None of this, I thought, required any talent. Even if it did, that wasn’t why she was complimenting me.

“So,” she said, “was this where you and you-know-who had your little love nest?”

“Who?” I asked.

“Don’t who me. Liz.”

“Oh,” I said. Oh, I thought, dumbfounded suddenly by Fate’s operations. She’d believed me back then.

In response, I kissed Naomi, because I didn’t want to lie anymore.

“All right, Peter Proton, let’s see those superpowers in action.”

My superpowers. One of these, I was starting to realize, was detachment. When Naomi and I were together, it was as if my mind rode a thermal above our bodies, my wingbeats as quiet as my other exertions. I was tireless because of this levitation and distance, and terrifically lonely, sometimes strangely angry. And this anger I occasionally took out on her with an endurance whose limit I’d yet to touch and which made her delirious with pleasure. But more than anything, when we were together, I was baffled—the feeling bordered on defeat—not only because I could not recapture the intensity of our first time but also because the further removed I was in mind and body from her, the more delight Naomi expressed, the closer I brought her to me. I thought it was supposed to be the opposite. Was that what had happened with Amanda? Something must be wrong with me, I thought, with my heart, I was certain of it, attracting, as I had, the opposite of what I’d wanted. “I love how you touch me,” Naomi whispered afterward. “I love how you just…throw me around.”

On the mornings when I wasn’t shooting, I still came into Manhattan. On these days, it was Naomi who drove me into the city—this after we dropped off Danny and Jackie at their day camp’s bus stop and then returned to the house for what Naomi had begun to call “the pushy” in a girlish voice that sounded disturbingly like Danny’s. It was an act we always prosecuted in my room, since my side window faced the house’s driveway, with a clear view of Melville Lane. Afterward, we showered separately. The marble floors in my bathroom were always so cold and slick with steam, which also fogged the mirror over the sink. No matter how often I wiped its glass to see myself, I disappeared again. I’d dress for my day. I’d wait at the foot of their entryway’s stairs. Naomi would appear at the landing, freshly made up, and as she descended, gently dinged the railing with her ring.

Naomi and I didn’t speak much during the drive into Manhattan. What was there to say anymore? Our destination was Sam’s office, a five-story building on Thirty-Fifth Street between Eighth and Ninth. The company’s name, the only one on the buzzer, was Shah Shirtwaists. You entered through a short, dimly lit hallway. On the left was an antique, manually operated birdcage elevator. Straight ahead was the main office, whose walls were fashioned of exposed brick and divided by black wrought-iron beams. It was high-ceilinged and had an open floor plan, with the exception of Sam’s glass-enclosed workspace at the very back. When you entered, there was, to the immediate right, a receptionist’s desk, unmanned, and, to the left, running the length of the entire area, a row of seven desks, each occupied by an older, nattily dressed gentleman—suit, tie, Jew—except for the one at the end and nearest Sam’s office, which was reserved for Naomi, a part-time salesperson at the company. So far as I could tell, these men spent their entire day on the phone, departing for lunch en masse at twelve on the number, departing at five on same, schlepping past me, at the front desk, in Seven Dwarfs fashion and, before leaving, saying their schlumpy, schmaltzy, kvetchy, kvelly, menschy, schlimazely, alta-kaker-y goodbyes.

Answering the main line and greeting the rare visitor—my desk was perpendicular to the office’s front door—was my job, for which Sam handsomely paid me on a per diem basis, and one I enjoyed more than any acting job in my entire life. It was Naomi who trained me; it was here she’d first been employed by her husband. “You want to learn any business,” she said, “you start as the company’s receptionist.” In later life, I’d find this to be true, but I cannot say I learned anything about Sam’s business during my short stint manning the phones, although I did love operating the switchboard, a gray metal contraption with a rotary dial on its left and, on faded, cream-colored tabs, the names and extensions of every employee, these still stamped clearly on my memory. I cannot say why answering the phone and directing a call or taking a message pleased me so; it was, perhaps, the sheer mindlessness of it, the uncomplicatedness of it, the comparative lack of responsibility. Or the fact that the office’s volume was never too heavy, my supervision cursory, which allowed me to generate my Griffynweld campaign’s entire spreadsheet of random monster encounters.

Naomi took me to lunch on my first day. She waited until Sam and the salesforce had left and then approached my desk and said, “You hungry?” When I nodded, she said, “I want to show you something first.” Instead of leaving, she stepped onto the antique elevator, where I joined her in the car. She closed the accordion cage, which made a great bash, and cranked the deadman’s lever to U. “Next stop,” Naomi said as we climbed, “fifth floor: towel terry, French terry, terry storage.” The pulleys groaned, the pistons pffed, the heat rose as we did. Each floor that sank past was dark but for the ceiling-high, street-facing windows, these covered by papyrus-colored shades whose edges were radiant with sunlight. Naomi pulled the lever and we stopped with a sound that resembled train couplings colliding. Naomi opened the gate, and I stepped off the car. It was dim as a cavemouth and absolutely stifling up here. My steps on the thick hardwood planks were muffled as they were on the concrete soundstage. The air was so oppressive, there was so little circulation, it made me want to gasp. On rows of pallets were stacked enormous rolls of terry cloth, many in disarray, come loose and unspooled. Some were in mounds piled waist- and shoulder-high; others even taller, so that in the low light they resembled sand dunes. One spark, I thought, and the building would explode into a fireball. Naomi took off her suit jacket, removed her shoes, and climbed onto the nearest hillock on her hands and knees. Then she stood and began to walk atop this rolling landscape, pausing to turn to look at me and then continuing with her arms out to the sides for balance. She ascended one of the largest piles and then she faced in my direction. She smiled as she let herself fall, disappearing from sight. I found her lying in a great impression, arms outstretched and legs spread, laughing to herself. I too leaped from this precipice to land on my back with a dusty thump, and then she embraced me. The air was desiccated as a desert, and later, I watched motes through the window’s glowing frames, my shirt soaked through by then, my hair heavy with fibers, my hand in Naomi’s as we stared at the black ceiling.

“Let’s get you fed,” she offered, pulling me up from this nest’s depression.

Twice we were nearly caught.

One afternoon, while parked again at the Dead Street, Naomi pushed me away from her in the back seat and refastened her bra.

“This is teenage stuff,” she said. “We should be doing this in a bed.”

My solution was so obvious I couldn’t believe I hadn’t suggested it sooner: “My apartment’s only a block from here.”

At this, she knocked her palm to her forehead and, in imitation of me, said, “I could’ve had a V8.”

She took her time, when we arrived, to consider the place, Dad’s black-and-white photographs, his signed scores from The Fisher King and Jacques Brel. I took her out onto the terrace, told her how Oren and I liked to throw eggs at people at night. “Boys will be boys,” Naomi said. A pigeon landed on the railing, considered us for a moment, and then flew off. I asked her if she wanted to see the roof and she replied, “It sounds romantic. Maybe later, sure.” She opened a cabinet in the kitchen, surveyed its supplies of dry and canned goods, in case, I figured, we might have to ride out a nuclear winter here. She considered her appearance in the dining room mirrors and, when I stood next to her, smiled.

“Look how cute we are together,” she said.

“Want to see where I study?” I asked.

When I opened the door to my closet, she leaned into the space with her arms crossed, as if it were a clifftop’s overlook and I might push her over its edge. I clicked off the light and led her to the room I shared with Oren. She considered my Farrah Fawcett and Dallas Cowboys cheerleaders poster. “I have the top bunk,” I explained, but when I indicated she should climb the ladder she said, “Uh-uh.” So I continued to my parents’ room.

Taking a seat on their bed, Naomi asked, “Is this all of it?” I assumed she meant the apartment, and I nodded. She considered my mother’s bookshelves. She turned to look at the window, facing the river. “Oh,” she said, “that street there leads to where we park.”

Later, on my knees, glancing between my mother’s books and the underside of Naomi’s chin, spying our single body, now and again, in the blackened reflection of the TV’s screen, feeling her feel my tongue’s tiniest touch, its tip’s tensile adherence to her skin, like a starfish’s feet, send shudders through her stomach, I heard the front door bang shut. Naomi rolled away from me, scooped up her clothes, and disappeared into my parents’ bathroom.

It was Oren.

“Hello?” he said.

I dove under the covers and pretended to be asleep. I could hear him open and close several drawers in our room, and then he peeked into Mom and Dad’s door.

“What are you doing here?” he asked, and entered.

I did my best groggy-disoriented groan and, after a big stretch, moaned, “I could ask you the same thing.”

Oren wasn’t buying it. He held up a plastic bag from Zabar’s. “I came to get some underwear,” he said.

I sucked my teeth. “I must’ve fallen asleep.”

“Naked?” he said. Then he glanced at the closed bathroom door before looking back at me.

I shook my head as if to say, Don’t even think about it. While I was certain he wouldn’t disobey me, I was so scared I could barely keep my voice from cracking.

Oren snorted, and with a delivery that was a little too loud, that cruelly increased my discomfort, said, “Some summer, huh?”

“You’re telling me.”

“How’s living with the Shahs? You get to ride around in Sam’s Ferrari?”

“Every day,” I said. “I’m working at his company too.”

Oren’s expression darkened. “What do you mean?”

“I’m answering the phones. It’s the best way to learn the business.”

Oren was enraged. “You already have a job.”

“It’s just part-time.”

“That should’ve been my job,” Oren said.

“What are you talking about?”

He swung the bag at my head and I blocked it.

“Why are you always so mad at me?” I shouted.

“Because you hog everything,” he said.

Then he stormed out.

Traffic was terrible on the drive to Great Neck. From the FDR Drive, I could see the endless queue we were in, forking in both directions, east across the Triborough Bridge and moving at a snail’s pace across the river, above Randall’s Island. How much life was wasted like this? How much time, when it was added up, was idled away in this idiocy? How was I supposed to know that Oren wanted to work for Sam? And why didn’t I figure that out beforehand? Why was I so selfish?

“Why so quiet?” Naomi asked, turning off the radio.

“I don’t want to talk about it,” I said.

Why was I here?

“Someone’s in a bad mood,” Naomi said, and turned the radio’s volume back up.

The second time was at the office. It was day’s end, and I had decided I needed to see Griffynweld in its entirety. The staff had already left, along with Sam. Naomi was working at her desk. I’d spent the slow afternoon photocopying all of my world’s various regions, taping these together on the floor behind my desk to form a complete map. When these puzzle pieces were all connected, the result was as big as a queen-sized bed. I sat cross-legged before this, feeling a tremendous sense of accomplishment, reveling in the detail contained in each landmark, the various keeps and castles and dungeons that had once filled individual notebooks now marked on visible coordinates. I sensed Naomi behind me.

“Wow,” she said, and kneeled to join me on the floor, “what’s this you made?”

“It’s the world I’ve been building all summer,” I said.

“What’s all this for?” she said.

“My friends. My brother. It’s a game we play.”

“How does it work?”

“The Dungeon Master—me—creates a universe that has an overarching story, a beginning, a middle, and an end,” I said. “But there are smaller stories, adventures, that take place in between. Like here.” I leaned over the map and tapped the two towers icon at the southeastern tip.

“It kinda looks like New York,” she said. Then she touched the map.

“This place, everything about it, is in this notebook.” And I flipped through the spiral notebook containing the notes and maps, every room charted with treasure and traps. “And a group of players, who create characters of their choosing—they pick their race, class, and attributes—tell those stories with me. So the trick is to listen to their stories, to partly adapt the game to them, to let them help determine the game’s flow,” I continued, tracing the snaking shape of the Cronos Canyon’s river, “and to sort of guide them, while also putting obstacles in their way. Using these dice. To account for probabilities, for chance. It’s also my job to nudge them toward the places they need be, to gain experience and weapons and magic in order to acquire everything necessary to complete the campaign. Which is the way it becomes our story. Together.” I felt a little embarrassed having talked for so long but was also pleased with my summary.

“So what’s the big picture, then?” Naomi asked, and sat down next to me, to my right, but with her back to the map. “What’s the story?” She lay on her right hip, propped on her right hand, so that her shoulder nearly touched mine. I began to tell her, to outline for her the scourge that was the powerful and evil wizard, the Magus Moraga, and describe the band of teenagers who had witnessed their families and friends murdered by him and vowed revenge. I explained that, to defeat him, they would need to go on a quest for the pieces of the legendary Shield Sheafson’s armor, a set of relics more powerful than any weapon in all of Griffynweld, because it was invulnerable to all evil-aligned magic and could therefore destroy the tyrannical hold the magus had on his followers, freeing them, once again, to live peacefully among one another. While I was outlining all this, she said, “Well, I probably wouldn’t be much good at it. But I sure wish I could play with you.” And at this moment, I missed everybody in my life so terribly: my father, to whom I hadn’t spoken in weeks; my mother, who was so sad; my brother, who was so angry; Cliffnotes, only a few miles uptown but as far as Castle Pym was from Griffynweld’s eastern ocean; Tanner, probably sitting by the ocean now and on the same beach as Amanda. Even Amanda, who had treated me so poorly. So that when I came back to myself, seated here, on the floor, with Naomi, whose attention was complete, my loneliness was more acute than at any point in my life. When Naomi noticed my expression, she placed her palm to my cheek and kissed me, and I kissed her back, her cheek and her ear, to hide my face; and as during those first times together in her car, she raised her chin ever so slightly and closed her eyes, allowing herself to be kissed. “Never,” she whispered, “never in my life ever has anyone kissed me like you do. If I could only explain,” she said, “what it means to me.”

And then Sam walked in the office.

Because I faced the door, because over Naomi’s shoulder I could see it slowly swing in my direction, I was the first to react. Its glass was frosted, though I had an intimation it was Sam, I don’t know why, and because he did not expect to see us here, he’d proceeded hesitantly, surprised, I could tell, that the lights were still on, the office unlocked, Naomi—usually visible at her desk from that sight line—gone. And when to his right he sensed a presence, beneath him, and glanced in my direction, his view of his wife was slightly obstructed by my desk; her back was to him, his view of me obstructed by her, though she did not move from her position, did not jump up from where she was reclined, her eyes slowly opening as she registered his footfalls, at which point she remained still. There was time only for her to give me a fierce stare—it had just a hint of bravado in it, which I will never forget—for me to barely lean away, and while we were not, in fact, kissing at that moment, our faces were so close to each other’s, it was all so utterly compromising, that I was sure we’d been discovered. And what I will also never forget was how the sight of us registered with Sam—how he paused, so unprepared for this sight, that I was reminded of a deer twitching into visibility as you walk along a wooded road, the same initial perplexity obtaining between Sam and me as our eyes locked. Of what the next move was. And whose.

Sam, flummoxed, said only, “I forgot something,” and with a barely perceptible shake of his head—it was like watching someone convince himself he hadn’t seen a ghost—strode toward his office, assembled the papers for which he’d returned, and, as if for our benefit—we had not moved an inch—said to the both of us, “I’ll see you at home.” Then he walked out the door backward, pulling it closed behind him, as if to undo the entire episode.

I witnessed Naomi and Sam’s fight that evening. I was scraping the leftovers into the koi pond, enjoying the splash of the fish breaching for the food, when I heard them. It came as if from a distance at first, what they said was muffled, but because I was in the backyard and because it was nighttime, I could see them on the second floor, through their bedroom windows. Sam, miming an explosion in his head; Naomi, in response, jabbed her finger into his chest and then pointed behind her, as if he’d left something in the hallway that she demanded he retrieve. They fought differently from my parents; the distinction was sonic. Dad denied and bemoaned; Mom accused and wailed; pain and heartsickness were its tenor. Sam, meanwhile, mocked and dismissed; Naomi raged and demeaned; their tone was hateful—Naomi’s voice as guttural as Sam’s was high-pitched—and it scared me more than my parents’ fighting but did not stifle my curiosity. Naomi about-faced and marched out of their room, and I moved toward the very back of the yard, to stand invisible before the hedges and follow her progress, since the home’s bay-facing side was mostly glass. Naomi next appeared in the second-story hallway and made her way down the stairs. She entered the living room, where Danny was watching TV, and ordered her to turn it off. Above, I spotted Sam, framed in his bedroom’s middle window, both hands clapped to his cheeks as he contemplated the water; Jackie appeared to my left in the sunroom, oblivious to this conflict, a pint of Häagen-Dazs in one hand, a spoon in the other, until Naomi appeared, striding past her, toward the garage—she waved off her daughter’s question—to go for a drive, I guessed (I heard the door to the garage slam), because I didn’t see her for the rest of the evening, and she didn’t find me in my room that night.

In the days that followed this row, and without fail, it was Sam who took me to lunch. I feared an accusation was forthcoming. In the meantime, he seemed glad for my company, energized at the prospect of introducing me to new cuisine. “The world is our oyster,” he said, laughing, and he took me for these at Grand Central Station, insisting I drench the two dozen we split in mignonette, in horseradish, in cocktail sauce. Next we had the fried scallops with black garlic-ancho aioli. “The spice,” Sam said, “puts hair on your chest.” He chewed with his mouth open; he laughed at the food’s heady flavors; his good mood was both infectious and a relief. He took me for Korean the next day, introduced me to kimchi, challenged me to go toe-to-toe with him and see who could eat the hottest dish.

“If I tap before you,” he said, “I’ll give you five dollars per course.”

“What if I tap?” I asked.

“You tap,” Sam replied, “and you still get a free meal, how’s that for a bargain?”

“Bet,” I said, and we hooked pinkies.

It was a relief to be away from Naomi. It was a comfort to have Sam close. I did feel guilt deceiving him. Playing the part of his surrogate son, I could throw off the role of Lancelot, bedding the queen and destroying the kingdom. There was a lightness, a glee, in being the mentee. I won the fire noodles course, as well as the stir-fried octopus, but conceded at the pork cutlet—the “dreaded ‘drop-dead donkatsu,’ ” Sam intoned as the waiter placed the smoking plate between us. “Don’t worry,” Sam said, as I fanned my tongue and drank glass after glass of ice water, “we’ll get milkshakes afterward to cool the heat.”

The next day we brought beef souvlaki back to the office and ate at our desks, letting the paper catch the glistening green and yellow peppers that squished from the bread. Sam loved to lick the orange grease from his fingers afterward—I had never seen someone actually do this—sealing his lips to his digit’s lowest pad and then pulling to the tip, making a pop at the top and then moving on to the next, ending at the thumb. It was an act I spied Naomi watching from her desk, over her glasses’ bridge, and which, upon its conclusion, caused her to raise her own hands as if she were drying a manicure, the expression on her face one of shocked disgust. We had gyros on Friday, and that afternoon, while Sam was out of the office at a meeting, I called Naomi’s extension and told her to meet me on the elevator. And as soon as we were rising in the car together, I pushed her against the wall and kissed her, at which point she pushed me away and groaned.

“What?” I asked, my heart pounding, because she’d made the same growl with Sam.

“Nothing,” she said, and yanked the deadman’s lever to D. “Just please go brush your teeth.”

It was now Sam who drove me home in the evenings. I admit this too was a relief: to be under his surveillance, to lose the window of opportunity with Naomi, since within his sight I could do little wrong. But the silence brought on by this change in routine was for me almost unbearable. Here, I sometimes grew most paranoid, I expected an accusation at any moment, and on that first drive home together the actor in my soul made his appearance almost immediately.

“Can I get your advice about something?” I asked, and, after a beat, added: “It’s a girl problem.”

Sam downshifted, kept his eyes on the road. “I’ll be happy to help if I can,” he replied.

I told him the story of Amanda, from our meeting at Nightingale through the school year, from babysitting to the dinner with her dad, the kiss on the night of her birthday, culminating, of course, with that dreadful weekend in Westhampton—“Ah,” Sam said, “now I get why you were so upset that day”—and concluding with my question: “What do you think I should do?”

We’d arrived in Great Neck; we were on Saddle Rock’s residential roads. Sam pulled over. “For starters,” he said, proving he had been listening to at least part of my story, “you need to learn to drive a stick.”

This was how we spent those final evenings together. With me, driving the Ferrari all over Great Neck, wending our way down to University Gardens, then up to Kings Point, along East Shore Road, the nighttime vistas of Manhasset Bay ripping alongside us. Other nights, we crossed over to Port Washington and Sands Point, and then pushed east to Hempstead Bay, driving with the windows down, the salt in the air so heavy at times it was like eating an oyster again, the automobile exhaust carried on the eastbound breezes from Manhattan, whose glow on the horizon blotted the stars. I got the hang of finding each gear’s sweet spot, a conversation in resistance and inertia, between the road and the V12, always seeking that balanced feel, that zone where the car was never redlining but holding power in abeyance. “Accelerate into the turn,” Sam said as we leaned to the right. “Trust the suspension to claw the road.” We headed south again, to Greenvale, bearing east on 25A to East Norwich—Perfect names, I thought, for Griffynweld—continuing on to Oyster Bay, Sam and me driving for hours, all the way east to Stony Brook, where we parked and could spot, to the west, the Eatons Neck Lighthouse, its beam’s flash and revolution fingering the sound while Connecticut’s shore twinkled across the water. We got pulled over twice during these lessons, Sam producing his Police Benevolent Association card and badge for the officer, who considered it and, after disappearing briefly to call in the plates, said only, “Thanks, Mr. Shah, just make sure that next time your son has his permit with him.”

“My son?” Sam chuckled when we were back on the road. “Makes you wonder who’s your mother.”

And oh, the houses I saw on these long drives. Mansions with columns and verandas, their crow’s nests looking out over the waterfront. Their foyers lit by gargantuan chandeliers. Their old-world masonry and landscaping, their limestone and copper flashing mottled with the sea spray’s patina, their ivy-covered chimneys and two-boat slips. Their lawns for lawn’s sake, as if grass were a staple crop. The millions of ways there were in America to make millions. The beguiling edifices of the rich that proclaimed more, more, more. What to do with such plenty? What to make of such wealth? How to live your life? Why did Sam bring me here? Is it possible that he simply wanted the company? Was he planning to shoot me and dump my body in the Sound? Or did he want to justify?

“The middle class grows,” Sam said, “the middle class needs cheap clothes. When I was your age, when it was time for me to go into the family business, this fact was as bright as that lighthouse’s lantern back there. But of this, I was sure: open up the borders, get rid of the tariffs, manufacture overseas to reduce your labor costs and increase your margins. Deregulate all of it, and then it’s just an equation. You, the government, you cut my taxes to swell the middle, even if the middle isn’t what it used to be, and guess what? The middle’s less will become my more, and the only solution when the economy tanks will be to tax me even less, while I laugh all the way to the bank. These next few decades—it’s going to be like having a bucket when it rains. Because if you’re rich in this great country, you’re in like Flynn. You’re rich, first. You’re not Jewish or Muslim or yellow or brown. You’re rich, and you’re safe. Safe from the very place you call home.”

I touched 110 on the straightway.

“The truth of it is I knew there was no risk in this business when I started. When the game’s gamed it’s game over. I knew that if I just put in my time, there was mostly only reward. But risk,” Sam said. “Balls. Nerve. No safety net. That, my boy, is the provenance of your father. Maybe it’s your provenance too.”

I’d lost count of the days since Naomi had last found her way to my bed. Something had happened. She seemed chastened, wary in Sam’s presence, cool and formal toward me. She avoided eye contact. She mumbled nonsensically. On the nights Sam and I did not drive together, she excused herself after dinner and retired to her bed, leaving Danny, Jackie, and me to do the dishes and then spend the rest of the evening watching MTV. It had premiered at the beginning of August and it was all the girls did, it seemed. Naomi sometimes joined us, though she sat as far apart from me in the room as she could manage.

But on the last night we spent together, when Sam and I arrived from Manhattan, Naomi seemed back to being her old self. She greeted me warmly, kissed her husband with an exaggerated pucker on the lips, and, after the big smack, said, “Have I got a surprise for you.” She led us to the kitchen. “From Marvin Himmelfarb at Ralph Lauren.” She held up a bottle of Nolet’s Reserve and then, with a flourish, a bottle of Petrus Pomerol.

Sam brightened, considering the label. “Nineteen sixty-one!” he said. “What did you do to deserve this?”

“Let me fix you a martini, and I’ll tell you all about it.” She gave Sam another big flirty smooch. “I brought home some steaks. They had a great price on the filet at the butcher.”

“Fantastic,” Sam said. “I’ll decant the bottle.”

Later, after Danny, Jackie, and I had scraped the fat into the koi pond, we came back inside to find Sam asleep at the dinner table.

“You two,” Naomi said to her daughters, “go start your bath. I’m going to give your father another antihistamine.” Then to me: “So he doesn’t snore from the sulfites.”

Did Naomi know it was her last chance to show me that this was what we shared? As I watched her above me, it seemed, at times, as if I were only incidental, a bystander to her performance. She wanted to be unforgettable. She wanted us, I am certain now, to be something she might never forget, that she might tend henceforth, like embers. She slapped me occasionally; she stiff-armed my face, leaning with all her weight, palm to my cheek, and held me there. She pulled her own hair, gathering fists of it by her temples, and shook her head. And for a long time, at the very end, she just kissed me, and I kissed her back, and this kissing felt like a free fall in pitch-darkness, felt like something endless.

It was sometime in the middle of the night, but, waking, I knew I was not the only one awake. Like a dog’s ear for high pitch, I heard a sound, one I could barely discern or distinguish, and I got out of bed to find the source.

Naomi was seated in the middle of the front hall’s staircase, in her slip, crying.

She looked up and wiped her eyes and waved for me to join her, then took my hand and turned me around, so that I was seated with my back to her, between her legs, which formed chair arms as if she were my young king’s throne. She pressed her face to my neck and nuzzled me there and cried, silently, her body shaking. Her forehead was hot. She calmed down, finally, and for a long time just sat with her arms weaved around my neck.

“I don’t want to go upstairs,” she said. Then: “I don’t want you to ever leave.” Then: “I don’t want to lose my family.” Then: “I don’t want to be with Sam anymore.” Then: “I want to wake up in your bed one morning.” Then: “I don’t want my daughters to ever be this unhappy.” Then: “I don’t want to be scared anymore.” Then: “I don’t want to keep hating myself.” Then: “I’m so sorry for what I’ve done to you.”

She kissed the back of my neck, at the very base, and rose to her feet and left me there.

Adults, I think now, were the ocean in which I swam.

There comes a point, even in the summer, when you want the season to end.

That evening, Danny, Jackie, and I were in the living room, watching MTV. If you watched the channel for long enough, the programming cycled through the same set of videos, but that did not (as yet) blunt our fascination with any of them, our determination to memorize every close-up of the climactic drum fills and guitar solos, these teaching a whole generation how to play air guitar and how to vogue. Nor did it diminish every tiny pleasure we took in certain moments we’d memorized. Of Stevie Nicks, for instance, blatantly blowing her lyrics as she lip-synced with Tom Petty in “Stop Draggin’ My Heart Around,” the duo dressed in black, and Nicks, with her witchy frizzy blond hair, reminding me of Naomi. Like Sam, the lead singer of the Buggles (“Video Killed the Radio Star”) wore Elton John glasses, and his keyboard player made it appear that the height of virtuosity was to play two synthesizers at once—“We can’t rewind,” I sang, to Danny and Jackie’s delight, “we’ve gone too far!” During the guitar solo on “You Better Run,” Pat Benatar would shake her head and rake fingers through her hair, and it was part and parcel of my transformation that nearly every rock song was so obviously about sex that I wanted to cover Danny’s and Jackie’s still-innocent ears. As for “In the Air Tonight,” what did the lyrics mean? Where was Mom? Dad? Oren? “The hurt doesn’t show,” sang Jackie, a thumb to her mouth in place of a mic, “But the pain still grows,” Danny sang, picking up the line. “It’s no stranger to you and me,” I roared. And while they played the air drums and danced like little go-go girls, I went outside to feed the fish.

It was dark in the yard, and after feeding the koi I walked to the lawn’s center and faced toward Manhattan, which I missed, which like my heartsickness glowed above the hedges and killed the sight of the stars. And then I heard Sam and Naomi fighting. The back of the Shahs’ home, as I have mentioned, was more glass than brick, and at night it was a tableau vivant. I turned around to see the girls dancing to The Who’s “You Better You Bet,” and then looked up to the Shahs’ bedroom on the second floor.

They’d gone straight to verbal haymakers and weren’t even trying to keep it down for our sakes. They followed the argument, or it followed them, from their bathroom and back to the bedroom, where it was Naomi who went for the sword first. Sam wrestled for control of the saber back, their two sets of hands upraised and firmly gripping the handle, as if they were trying to touch their twelve-foot ceiling with the blade’s tip. Sam, who managed to wrench the weapon from his wife’s clutches, now raised it above his head; Naomi, reaching out in protest, backed toward the door, screaming at him, and then ran. Downstairs, Danny and Jackie were still dancing, the TV’s volume blasting the Pretenders’ “Tattooed Love Boys,” the pair of them headbanging in front of Chrissie Hynde’s face, before freezing at the sound of Naomi’s scream. As if practiced—as if they knew this was not a drill—the girls dashed behind the curtains, their backs visible to me in the windows. And into this room the husband and wife appeared: Sam still with sword in hand, marching patiently around the coffee table, which Naomi, also marching around, kept between them. She bolted, finally, out of the family wing, with Sam right behind her, shouting as he followed her through the dining room. Here she turned to fling some of their china in his direction, the plates gouging the wallpaper as they broke against the wall, and then made her way into the kitchen, where I next spotted her walking backward again, now brandishing a chef’s knife, which she clumsily threw at her husband, its blade dinging on the tile, before she raced into the sunroom and, using the same strategy as earlier, placed the tulip table between them. With one hand, Sam tossed this aside. Naomi, surrendering, fell to her knees. But Sam let the weapon fall at his side and covered his face. At this, Naomi stood. Over Sam’s shoulder she spotted me and, sensing rescue, made for the door to the yard. He too turned and, spotting me, yanked her collar and threw her to the floor and, picking up the saber, marched in my direction. He pushed the door open. Naomi screamed, “No!” When she tried to follow, he turned and shouldered the door closed on her pinkie, which got caught in the jamb. The top half of her finger separated at the knuckle and bounced into the koi pond, where it floated for a second before one of those soft mouths rose to the surface, and ate it.

I ran.

Around to the front of the house, I fled, pursued by Naomi’s howl. I stopped on the street, looking at the other houses. I didn’t know any of the Shahs’ neighbors. I didn’t even know if the Shahs knew their neighbors.

The door of the garage was still up. I opened the door of the Ferrari, pulled the visor, and caught the keys before they landed in my lap. I dropped the car into gear and burned so much rubber I couldn’t see their house in my rearview mirror for the smoke.

I’d made the drive into the city so many times with both Sam and Naomi I knew it like a commuter.

And I knew the peace and quiet that attends the solo commuter’s trip—the time it gave me to collect my thoughts, which were, in my manner of coping back then, entirely unrelated to what had just happened. Passing Flushing Meadows, I spied the Unisphere, that giant globe, and considered how few places I’d been to in my life besides New York. The Observation Towers, topped with their flying saucers, these World’s Fair structures, run-down and rusting and in need of restoration. Manhattan came into view from the Queens side. When he was my age, did Dad marvel at its skyline as I did now? Is the city ever more wondrous than when seen from afar, at night? When the sky is black, when its buildings’ outlines are rendered invisible? There are more windows in New York than people, I thought. How to begin to calculate such a number? I turned on the radio. Dad’s commercial for Bell telephone played. Reach out, he said, and touch someone far away. Coming over the Fifty-Ninth Street Bridge, the Roosevelt Island tram rose into view on my right, but the car was empty.

Was this how adults fought with each other?

At our building, I pulled into our empty parking space and cut the engine. The needles slammed shut against their pegs.

I said hi to Carlos, the night doorman, in the lobby. “Long time no see,” he said.

Standing before our apartment’s door, I reached between my shirt’s collar and, from where it hung on its ball chain, produced the key.

I had never been so happy to be back in my own bed, I thought later, lying in my top bunk. I had never been so happy to be home.

Dad shook me awake the next morning—I’d slept in, I could tell, by the angle of the sunlight on the building across the street. “What are you doing here?” he asked.

I hugged his neck, which seemed gargantuan and smelled of Skin Bracer. I let him carry all my weight, and when he tried to ease my grip, I clutched him harder.

“Craziest thing,” he said, as I held him. “I got in just now from D.C., and guess what? There’s a goddamn Ferrari in my spot.”