How Your Set-Point Rises and How to Lower It

I like to think of our set-point weight as being like our set-point body temperature. While the norm might be 98.6°F, your set-point body temperature rises and stays elevated when something is wrong with your body. Both set-point body weight and set-point temperature can be forcibly lowered temporarily via energy deprivation (starvation for body weight and ice baths for body temperature), but since neither of these approaches addresses the root cause, both do more harm than good over the long term.

But when we heal our body, instead of just attending to the symptoms, our body weight and body temperature return to and stay at healthy levels. A healthy body automatically maintains a healthy weight in just the same way that it automatically maintains a healthy temperature.

When it comes to this metabolic healing, there are two primary hormones involved with our clog: insulin and leptin. Insulin is produced by the pancreas and through its interaction with our cells and brain, determines whether we are storing or burning fat. Leptin is produced by our body fat and, through its interaction with our gut, central nervous system, and brain, regulates how much food we eat, how much energy we burn, and the amount of body fat specified by our set-point.

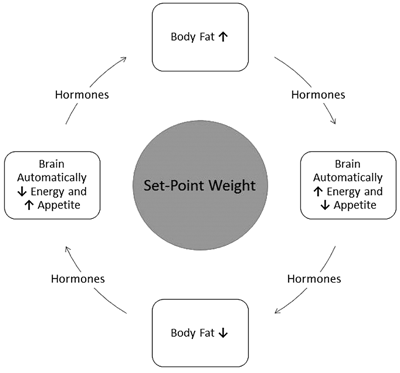

Let’s assume we are unclogged. When our weight starts rising above our set-point, hormonal signals cause our metabolic rate to go up, our appetite to go down, and our body fat to get burned. This prevents excess fat from sticking around for long. We stay at a slim set-point without trying.

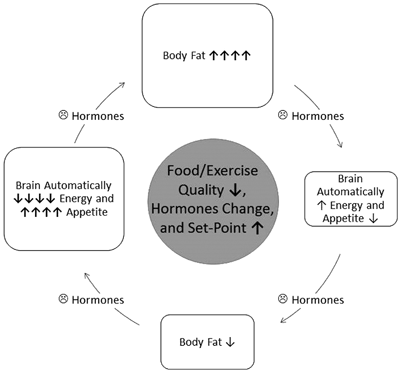

But when we feed our body low-quality foods, it becomes unable to effectively respond to these hormones. Without those hormonal “burn fat” signals, the metabolic processes that otherwise keep us slim do not happen. Once our body is not effectively responding to hormones like leptin and insulin, we become insulin and leptin resistant, and our body starts overproducing these hormones—causing a hormonal clog. For example, some very obese people have been shown to have up to twenty-five times more than a normal level of leptin circulating in their bodies. Chronically high levels of these hormones make our body think that an abnormally high level of body fat is normal. Since our body does its best to balance us at a set-point it thinks is normal, it keeps us at an abnormally high level of body fat. When we eat poorly, we raise our set-point.

A NORMAL SET-POINT

A FALLING SET-POINT

A RISING SET-POINT

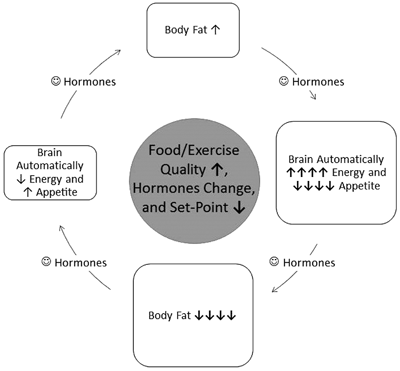

HOW TO LOWER YOUR SET-POINT WEIGHT

You may be thinking to yourself: “This set-point science is all well and good, but what about people who lose weight by eating less and exercising more?” Our set-point doesn’t mean that it’s impossible to lower our body weight by eating less and exercising more or that it’s impossible to raise our body weight by doing the opposite. We can do all sorts of unhealthy things to temporarily stray from set-points in the short term. As I noted earlier, we could sit in an ice bath for as long as we can tolerate, and it would temporarily lower our body temperature just as starving as long as we can tolerate will temporarily lower our body weight. However, the set-point wins out over the long term. It shows why we have such a hard time keeping weight off when we focus on calorie counting. We can absolutely stray from our body weight set-point temporarily via food and exercise quantity, but we cannot adjust our set-point itself unless we change the quality of our food and exercise. The higher the quality, the lower our set-point.

Consider a nutritional study performed on rats conducted at Penn State University by Barbara Rolls, PhD, chair of Nutritional Sciences.16 The rats were divided into two groups:

Low-Quality Group: Rats with access to unlimited low- and normal-quality food.

High-Quality Group: Rats with access to unlimited higher-quality food.

As expected, the Low-Quality Group gained weight and the High-Quality Group did not. But here is where the study gets interesting: After the Low-Quality Group became heavy, Rolls took the low-quality food (processed starches and sweets such as such as chips, cookies, and crackers) away from them. Now both the overweight Low-Quality Group and the regular-weight High-Quality Group had access to the same food. The Low-Quality Group, though, stayed at their heavy weight.

Wait a second. How can the same diet keep one group of rats heavy and keep another group slim? Because the Low-Quality Group had changed their set-points.*

The High-Quality Group started with a normal set-point and remained at a normal set-point, thanks to a diet of whole, nutritious foods, and therefore maintained a normal weight. The Low-Quality group started with a normal set-point, increased their set-point thanks to a low-quality diet, and thereafter stayed at their heavy weight. Rolls attributed the change in the obese rats to “a long-lasting endocrine or metabolic change.”17 In other words, hormonal clog.

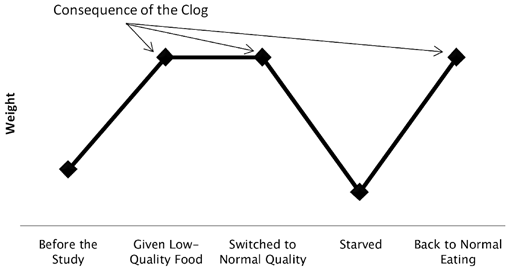

The study gets even more interesting. Rolls then took half of the heavy Low-Quality Group and fed them a diet of only higher-quality food, but much less of it. In other words, she made the heavy rats eat less. Lowering the quantity of food caused the rats to temporarily lose weight. However, as soon as Rolls stopped starving the Low-Quality Group, they returned to the heavy weight targeted by their recently raised set-point. They did not return to a standard rat weight. The low-quality food they ate at the start of the study raised their set-point and put them on a path of long-term weight gain.

THE IMPACT OF LOW-QUALITY FOOD IN ROLLS’S STUDY

Rolls’s study shows us that a steady diet of low-quality food can cause our set-point to rise—which is unsettling news for anyone who’s been eating the standard American diet for any length of time. But here’s the good news: studies from all around the world offer evidence that the metabolic and hormonal consequences of eating a low-quality diet are reversible.18 In their lead article “Neurobiology of Nutrition and Obesity” in the journal Nutrition Reviews, Pennington Biomedical Research Center researchers Christopher D. Morrison, PhD, and Hans-Rudolf Berthoud, PhD, noted that “diet-induced leptin resistance,” or the dysregulation of one of our key hormones in regulating weight control, “is fully reversible” in genetically identical mice.19 University of Washington researchers have also discovered that enjoying more whole-food fats—especially natural foods high in omega-3 fats such as salmon, flax seeds, and chia seeds—in place of refined, processed vegetable oils found in starch- and sugar-based junk food, reduces the inflammation in the brain that contributes to an elevated set-point.20 Additional studies go on to show that 80 percent of individuals with severe insulin resistance—another major factor of set-point elevation—can reverse the damage caused by an overload of sugar and make their cells more sensitive to insulin again by eating a higher-quality diet and exercising smarter.21 Finally, startling studies out of the Metabolism and Nutrition Research Group at the Université Catholique de Louvain in Belgium prove that when mice were fed a nutritious diet that restored their microbiomes, or healthy gut bacteria, the mice had “markedly improved glucose tolerance, reduced body weight and fat mass, and increased muscle mass,” without any changes in the quantity of calories they consumed.22

In each of these studies, the researchers were able reset the set-point of mice by changing the kinds of foods the mice were fed—not the quantity of what they were fed. In their own words, they were able to reverse “diet-induced metabolic disorders, including fat-mass gain, metabolic endotoxemia [inflammation], adipose tissue inflammation, and insulin resistance.”23 The data are clear: by increasing the quality of our eating and exercise, we can resensitize ourselves to fat-burning hormones, reduce inflammation, and enjoy a metabolism more like that of a naturally thin person.

We know from Dr. Rolls’s study that rats that were fed low-quality food ended up with higher set-points. But what about the impact of exercise? Wouldn’t rats that exercised more be able to lower even their elevated set-points?

The University of Utah’s Dr. Jeffrey Peck devised a test similar to Rolls’s study, dividing healthy rats into three groups.24 First, he looked at the impact of diet on set-point. Each group could eat an unlimited quantity of calories. The only difference was the quality of the calories.

High-Quality Group: Rats with access to unlimited high-quality food.

Low-Quality Group: Rats with access to unlimited low-quality food.

Quinine Group: Rats with access to unlimited food with a bitter substance called quinine added to it.

As expected, the High-Quality Group maintained a standard weight, the Low-Quality Group gained weight, and the Quinine Group lost weight. Peck then made each group of rats eat less of their type of food. All the rats temporarily lost about 10 percent of their body weight.

Peck then stopped starving the rats and they all went back to eating an unlimited amount of their chosen food. The High-Quality Group automatically returned to their standard rat weight. The Low-Quality Group automatically returned to their heavier weight. And the Quinine Group automatically returned to their reduced weight. As in Rolls’s study, after eating less, all the rats automatically regained weight, but how much they regained depended on their set-point, which was determined by the quality of their diet. In other words, food quantity temporarily moved them away from their set-point, but food quality determined the set-point itself.

Next, Peck wanted to explore the effects of exercise on these three groups, so he had his furry subjects burn calories by shivering away all day in a very cold room. All the rats automatically increased how much they ate to offset how much they exercised. Burning more calories simply made the rats eat more calories. Their set-point was un-changed.

Peck then freed the rats from the cold conditions, but continued the experiment. He kept all the groups on their respective diets while feeding them additional calories through a stomach tube. He wanted to see if a higher quantity of the same quality of calories would have an impact on the rats’ set-points. It did not. All the rats automatically adjusted the amount of high-quality, low-quality, or bitter food they ate in order to maintain the normal, higher, or lower weights targeted by their set-points.

Eating less did not cause long-term weight loss. The set-point won. Exercising more did not cause long-term weight loss. The set-point won. Having additional calories pumped directly into the stomach did not cause long-term weight gain. The set-point won. The only factor that did have an impact on rats’ long-term weight was the quality of their calories. That worked because it reduced inflammation, resensitized receptors, reregulated hormones, and therefore changed their set-point. Fortunately, recent research reveals a more enjoyable way of changing the quality of our diet and lowering our set-point. (No quinine-laced food for us.) Pablo J. Enriori, PhD, of the Division of Neuroscience at Oregon Health and Science University, has since published a study in the journal Cell Metabolism (March 2007) showing that returning mammals to the higher-quality diet they are genetically adapted to reverses the clogging and resulting raised set-point caused by a low-quality eating.

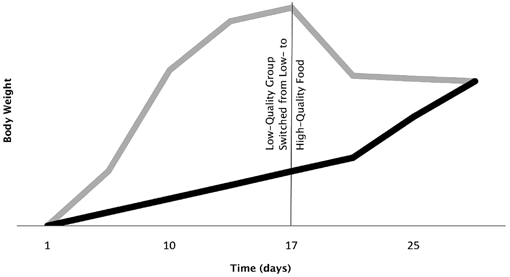

One more study proves this point. In Nancy Rothwell’s study at St. George’s Hospital Medical School in London, growing rats were divided into Low-Quality American Diet and High-Quality Natural Rat Diet groups.25 Rothwell let all the growing rats eat as much as they wanted for sixteen days. Keep in mind that both groups should gain weight, as they are young, quickly growing rats. On the seventeenth day the rats continued eating as much as they wanted, but Rothwell switched the Low-Quality American Diet rats to the High-Quality Natural Rat Diet. Here is what happened:

AUTOMATIC FAT LOSS

The young rats that were becoming obese quickly dropped all their excess weight automatically when the quality of their diet improved. The increased quality of their food readjusted their hormones; decreased neurological, digestive, and nervous inflammation; resensitized cells; and lowered their set-point. We can do the same once we stop focusing on quantity and start applying the science of quality.

Let’s look at the four major problems of the traditional quantity-focused fat-loss approach:

1. Eating less does not cause long-term fat loss.

2. Exercising more does not cause long-term fat loss.

3. Exercising less does not cause long-term fat gain.

4. Eating more does not cause long-term fat gain.

In the next few chapters we’ll look at what scientists have to say about each of these statements. They already know the answers and they can prove it. That’s good for us, because by knowing the facts, we can finally start to burn fat and protect our health permanently.