Chapter Five

Flattener #2 – The Energy Reserves and Resources Glut

We are not going to run out of oil any time in my lifetime or yours. The resource base is enormous and can support current and future demand.

Rex Tillerson, Exxon CEO

In the early 1990s, I had just finished my postgraduate degree and was ready to look for a job.

“There are only 40 years of reserves left. Why would you want to join the oil industry?” my best friend asked me. “Never bet against an engineer”, I replied half-jokingly. The world would need a lot of energy and a lot of oil to continue to grow, and the optimist inside of me believed we somehow would find a way forward, just like we did in the past. “If you give enough time and money to an engineer, he will eventually find a solution”. Technology has been, is, and will be king.

What energy scarcity?

Hydrocarbons are very abundant.

Coal reserves exceed 50+ years of current demand. Resources are even larger and would become available if and when prices increase.

Natural gas reserves exceed 100+ years of current demand. Resources are even larger and would become available if and when prices increase.

Even crude oil reserves exceed 50+ years of current demand. Resources are even larger and would become available if and when prices increase.

And it does not end there. The “new frontier” of methane hydrates (also known as “frozen methane” or “fire ice”) are ice crystals with natural methane gas locked inside. They are formed through a combination of low temperatures and high pressure, and are found primarily on the edge of continental shelves where the seabed drops sharply away into the deep ocean floor.

According to the British Geological Survey, “estimates suggest that there is about the same amount of carbon in methane hydrates as there is in every other organic carbon store on the planet”.1 That is, there is more energy in methane hydrates than in all the world's oil, coal, and natural gas put together!

It is worth reminding ourselves that shale gas and tight oil were known to exist, but had been dismissed as not commercially viable. And look where we are today!

The state-backed Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation (JOGMEC) has recently announced the production of methane hydrates off the coast of Japan, but any impact may not come until beyond 2020.

With or without frozen methane, what is clear is that there is no scarcity or shortage of hydrocarbon resources on planet Earth.

But, as one of my bosses once told me, “perception is reality” and consumer governments around the world, often influenced by geopolitics and other considerations, have created a perception of energy reserves scarcity.

The world is also addicted to hydrocarbons, and ever since the industrial revolution, economic growth has been closely linked to energy demand growth. Coal, natural gas, and crude oil have been at the core of the globalization, industrialization, and urbanization. Other non-hydrocarbon sources of energy such as nuclear, hydro, solar, and wind power have also contributed to energy growth, but at a much lower scale.

To better understand the reality, there is no better place to start than exploring the pricing and technological dynamics of reserves and resources.

Reserves and resources

According to the EIA, the world has produced about 1 trillion barrels of oil since the start of the industrial revolution in the nineteenth century. The extraction took place as prices and existing technology made it commercially viable. It would have stayed underground otherwise!

The world has another 1.5 trillion barrels of proven plus probable reserves that are both technically and economically recoverable at current prices.2

And there are another 5+ trillion barrels of crude oil that are known to exist, but that are not commercially viable at current prices or with current technology.3

The cut-off point between reserves and resources is a function of prices and technology. It is not static. As prices go up, resources become commercial reserves. As prices go down, reserves may become uneconomical resources. The frontier is changing all the time.

New technologies can increase reserves via “quantum leaps”. In 2003, the EIA4 revised Canadian reserves from 5 billion barrels to 180 billion (a 3600% increase) thanks to improvements in the extraction technology of oil sand. The revision catapulted Canada to the top three in the world, along with Saudi Arabia and Venezuela.

On the other hand, of course, reserves suffer a constant grind via consumption. Effectively, every barrel of oil consumed is one less barrel of oil available.

Replacing production and decline rates is one of the fundamental jobs of the oil industry. The replacement is achieved via a combination of new discoveries and additions to existing fields, both of which are challenging and require enormous investment …and time.

Crude oil concentration, but no shortage

Most people agree that the Middle East has vast resources of conventional oil and gas. I say “most people” because there are some conspiracy theories that question the real size and potential of the Middle East in general, and Saudi in particular. But I guess there are also some conspiracy theories that say Fort Knox does not hold any gold either. I suppose that would make it even, as the United States has enjoyed a great advantage of being the reserve currency of the world for decades. Yes, the value of the US dollar is an act of “faith” (that's what a fiduciary currency means), but people take great comfort in the large amount of gold held by the United States. Well, it is true that the US government is the largest gold holder in the world with over 250 million ounces, but it is worth noting that the gold is worth “just” $325 billion assuming $1300/oz.5 Very large, but certainly not enough to support a total debt of $17 trillion,6 or quantitative easing of $857 billion per month for years.

Beyond the Middle East and any controversy, most people agree that there are also vast conventional and unconventional resources in the United States, Canada, Mexico, Venezuela, Brazil, Russia, and even China.

Historically, the main problem was not the size or existence of the reserves. The main issue has been the asymmetric distribution of the conventional (“cheap”) proven reserves, with more than half of the “low hanging fruit” of cheap oil in the Middle East.

The high concentration of reserves opened the door to OPEC oligopolistic behaviour and nationalistic barriers of entry. Further constraints, such as geopolitical conflicts or embargoes, have exacerbated the impact even further. These dynamics have shaped the world of crude oil as we know it.

Already, the energy revolution is diluting the issue of “concentration of reserves”, thus reducing the world's dependence on Middle East oil and gas. Shale oil and tar sands are a reality and are already eroding the impact of geopolitical conflicts. The United States alone has over 24 billion8 barrels of recoverable shale oil, and is on track for full energy independence by 2020. Many other countries, such as Brazil, are also expanding their productive capacity and are expected to surpass many of the traditional major oil exporters by the end of the decade.

Furthermore, everyone agrees that other energy resources such as global natural gas and coal are also enormous. And that, unlike crude oil, these resources are more evenly distributed around the world. Concentration risk is not a major problem. There is natural gas pretty much everywhere. Even in Israel and Cyprus!

OPEC almighty

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) was created in 1960 as a permanent, intergovernmental organization, with the objective to “co-ordinate and unify petroleum policies among Member Countries, in order to secure fair and stable prices for petroleum producers; an efficient, economic and regular supply of petroleum to consuming nations; and a fair return on capital to those investing in the industry”.9

It is ironic that OPEC was born as a defensive mechanism from the producers against the glut of oil. The creation occurred at a time of transition in the international economic and political landscape, with extensive decolonization and the birth of many new independent states in the developing world. The international oil market was dominated by the “Seven Sisters” multinational companies, largely separate from the former Soviet Union (FSU) and other centrally planned economies (CPEs).

The large concentration of reserves is, as we say in mathematics, “a necessary, but not sufficient condition” for a successful oligopoly, but peak oil defenders often forget that OPEC is a cartel aiming to provide a “steady income to producers and a fair return on capital for those investing in the petroleum industry”.10 Peak oil defenders assume that the oil industry is an NGO that needs to “prove” growth to consumers at any price or return.

OPEC took control de facto in 1973, when the “oil weapon” was successfully unleashed for the first time, as its Member Countries took control of their domestic petroleum industries and acquired a major say in the pricing of crude oil on world markets. Since then, OPEC has operated one of the most successful oligopolistic cartels in history, effectively capturing a significant share of the economic rent away from consumers and refiners.11

But, following the oil shocks of the 1970s, crude oil was largely displaced from the industrial and power generation sectors by cheaper and more reliable sources, such as coal, natural gas, and nuclear. Since then, as discussed, crude oil has been mainly an input to transportation fuel, and with residual applications to other industries such as petrochemicals, while remaining as a “fuel of last resort” for power generation.

Since 1999, OPEC has kept an average of 25 million barrels per day production quota, with only moderate changes to adapt to price hikes.12 Despite the quota system, OPEC has consistently produced above it, and we must not forget that the quota system allows for a “cheat” buffer, preventing countries from exceeding much more than 20%13 cheat on targets.

And OPEC may be set to lose control on both ends of the spectrum.

When prices are low, because by default there is excess supply, they are forced to cut their own production and, with it, the revenues that fall from it. They have done it in the past, but there is a limit to how much and how long, as we saw in 1986 when Saudi Arabia “folded” and was moved into a volume maximization in search of market share.

When prices are too high, there is a strong incentive for demand destruction, substitution, and exploration. The 1970s saw the displacement of crude oil in the power generation sector. Once the forces come into play, the response tends to create a glut. Saudi knows the limits and threats well.

Reserve protectionism

Most of the Middle East and many other countries around the world have put in place barriers to entry to investment that have prevented them reaching their full potential.

But some of these countries are slowly opening up.

Look at Mexico, for example, where over the past 75 years Pemex has kept a monopoly in the oil and gas sector. The industry was effectively closed to foreign investment since 193814 as the government aimed to preserve reserves for domestic consumption.

In December 2013, the Mexican government presented a bill designed to change the constitution that would open the hydrocarbon and energy sectors to private and foreign investment. A revolutionary step that will in my view substantially increase foreign direct investment (FDI), strengthen Mexico's fiscal and external accounts, and lift its potential growth and employment. The reserves of Mexico are huge, and open the potential for significant infrastructure and growth over the next decade.

Marginal cost of production

During my debates with supply-side oil economists and engineers, I often hear, “Look at how expensive production is from Canadian oil sands. Prices will stay high”, along with other marginal cost arguments to justify that crude oil prices cannot go down.

Remember prices are set by both supply and demand. Not just by supply or marginal cost pressure. If a product is too expensive to produce, it may simply not sell as consumers switch to cheaper alternatives to satisfy their needs.

Look at the 1970s, when crude oil was priced out of the power generation stack. If a cheaper and reliable alternative emerges, crude oil may be priced out of the transportation sector too.

The monopoly of crude oil over the transportation fuels sector has been in place ever since the application of the combustion engine to transportation in the early 1900s. This is increasingly being challenged by electric cars, compressed natural gas vehicles, ethanol or biodiesel cars, and solar power. Yes, they are a small minority for now, but the dynamics are changing quickly.

The complacent assumption that crude oil has no competition can be a lethal miscalculation in the long run.

The “unconventional” resources

My view is very simple: “everything that goes in your tank is conventional”.

Yet, the industry tends to differentiate between “conventional” and “unconventional” resources, where “unconventional” refers to methods that are not “conventional” in our current technology and engineering statu quo.

Some people argue that unconventional oil “doesn't count”, which I find childish at best. Assuming that principle, no oil production is valid unless it's onshore surface drilling.

Furthermore, the distinction is not binary. There are many degrees of “unconventional”. Over the years, the technologies and techniques have improved steadily and are now major reliable contributors to global supply.

Yet, new technologies have often faced technical and environmental challenges during their early days. Look at offshore drilling, for example, with a plague of high profile accidents making it truly unpopular. But accidents become lessons. And the lessons have become new regulations and better practices, helping reduce the probability and severity of accidents. Altogether, time and time again, the frontier has kept moving forward.

Onshore drilling, the “conventional” method, became a reliable source of crude oil production. It was only natural that the exploration and production expanded into shallow water, initially in lakes near existing production fields such as Texas, Louisiana, and Lake Maracaibo in Venezuela. Drilling in lakes proved relatively easy.

The next frontier was offshore drilling, in the ocean, subject to the waves, tides, and adverse weather. The efforts started gradually after World War II, and by the end of the 1960s shallow waters were becoming a significant source of oil.

The next frontier was then deep-water, with exploration efforts focused on the “Golden Triangle” of Brazil, West Africa, and the Gulf of Mexico. By 2009, shallow and deep-water production from the Gulf of Mexico was 30% of US domestic oil production, contributing to the first increase in US domestic oil production in two decades.15

And then was the ultra-deep-water. In Brazil, improved seismic techniques identified a supergiant field with an estimated 5 billion to 8 billion barrels of recoverable reserves. The biggest discovery since Kashagan in Kazakhstan in 2000, it is expected to produce 6 million barrels per day, twice the current output of Venezuela, by 2025.

But the opportunities were also inland, literally “mining oil”. The large scale of the Canadian oil sands or the Orinoco Belt in Venezuela have been known for many decades. Developments in technology and techniques have helped increase production in Alberta, Canada. Conventional and unconventional output in Canada could reach almost 4 million barrels per day by 2020.

And the more recent one is tight oil, extracted from shale-like formations. Like oil sands, the vast resources were known of, and the development of shale gas via horizontal drilling and fracking has opened the potential for over 20 billion barrels in the United States alone, equivalent to adding half of Alaska, but without having to work in the Arctic north and without having to build a huge pipeline. Tight oil is already 3 million barrels per day today and expected to grow to 5 million barrels per day in the United States by 2020. The EIA estimates US technically recoverable resources of 345 billion barrels of world shale oil resources and 7,299 trillion cubic feet of world shale gas resources.16

And do not forget natural gas liquids, still the biggest source of nonconventional oil. Condensates are captured from gas when it comes out of the well. Natural gas liquids are separated out when the gas is processed for injection into a pipeline. Both are similar to high-quality light oils.

Discoveries vs. additions: “can we rely on finding new oil fields?”

Contrary to what many people think, most of the increase in supply comes from additions to existing reserves. Not from new discoveries.

When a field is first discovered, very little is known about it, and initial estimates are limited and generally conservative. The more the wells are drilled, and with better knowledge, proven reserves are very often increased.

The difference in the balance between discoveries and revisions and additions is dramatic. According to one study by the United States Geological Survey, 86% of oil reserves in the United States are the result not of what is estimated at the time of discovery but of the revisions and additions that come with further development.17

Let's look at discoveries. According to the IEA, Goldman Sachs, and Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA), an average of 3 billion bbl of oil was discovered each year between 2003 and 2005. This compares to 8 billion bbl per year from 2006 to 2009. Most of the discoveries over the last five years have been made in the deep offshore, with Brazil dominating on size, followed by the Gulf of Mexico, and Ghana. Onshore discoveries of large size have been rare and in general limited to Iraq (Kurdistan) and Uganda, although oil shales and field redevelopments in Iraq have provided very material additions to the pipeline of onshore oil projects.

Now let's look at the additions. For some reason, the analysis of resource additions tends to focus only on conventional oil “as we knew it in the late 1990s”. Why? Not clear. But by that measure, why don't we disregard any oil that is not onshore Saudi Arabia or why not disregard any oil that is not American Petroleum Institute (API) perfect? Furthermore, very much in line with most peak oil theories, the pessimistic analysis completely forgets nonconventional and liquids. By only including the addition of shale oil resources and heavy oil in Venezuela and Iran the reserve replacement is well above 120%.18 And not to mention the giant discoveries in West Africa, which have added to the base of low sulphur crude.

Ignoring nonconventional, pre-salt, and heavy oil today is equivalent to ignoring deep water in the 1970s, or oil sands in the 1980s.

The excess capacity at high complexity refineries of 8 million barrels per day provides plenty of processing capacity and at a cheap cost. Drivers and motorists do not make any distinction between conventional and unconventional. They only care about what goes in the tank!

It is also worth noting the trend of promised volumes has dramatically increased over the past five years to c.95% from historically c.75%.19 This proves that the “below to above ground” analysis of many peak oil defenders is not linear and that industry technology and delivery have greatly improved.

Sorry, no peak oil

We were wrong on peak oil. There's enough to fry us all. A boom in oil production has made a mockery of our predictions.20

George Monbiot

Peak oil is a myth

Over the years I have had many debates, including on television and in written media, with unconditional “peak oil supporters”.

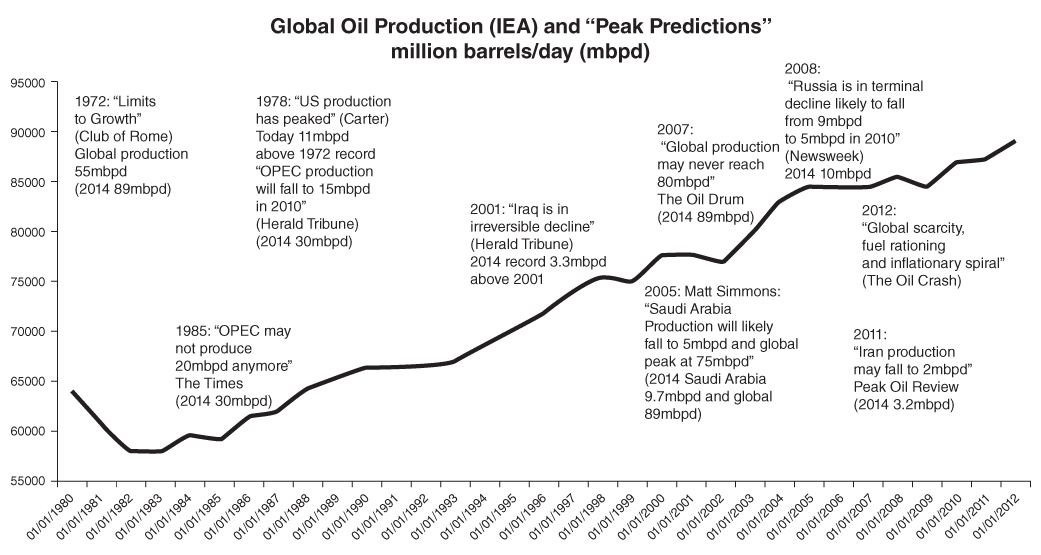

In 2012, during the Oil & Money Conference, Maria van der Hoeven, president of the EIA, alongside a panel of experts, said “This is the 33rd Oil & Money Conference. In 1979 in the first page of the Herald Tribune run the headline where President Carter said oil production had peaked, and the press said OPEC production would collapse to 15 million barrels per day in 2010. But here we are, global production is at record 87 million barrels per day, and OPEC produces 30 million barrels per day”.

Arguments like “population and demand will continue to grow”, “rising standards in emerging markets”, or “every barrel of oil that we consume is gone forever” are undeniably true, but the conclusions often implied from them such as, “we are running out of oil”, or “prices must continue to go up” are undeniably not true.

Global oil production and “peak predictions” (million barrels per day (mbpd))

And beyond our discussions, the peak oil theory is being disproved by the market itself both on the supply and demand sides of the equation. Supply is larger and more diversified than ever. Demand is growing at a slower pace with efficiency, technology, and less energy-intensive economic growth eroding peak demand. Supply has over and over responded to incremental demand. Just like demand has responded to incremental supply.

The core of the problem is an over-simplistic and static analysis, a dangerous mix of “realities and myths”, that misses the true complex dynamics of the energy markets and reaches the wrong conclusions.

Yet, despite the vast resources and dynamic defence mechanisms of the market, there seems to be an unconscious bias in our human brains that supports the notion of peak oil.

But the last barrel of oil will not be worth millions. It will be worth zero.

And by the time that decline is a real issue, substitution will be more than evident.

“The Stone Age did not end because of a shortage of stones”.21 It ended because humanity moved into the Bronze Age. And the Bronze Age did not finish because of a shortage of bronze either. It ended because we moved into the Iron Age. And so on and so forth, the world has continued to evolve thanks to new technologies.

And the “oil age” will be no different. The end of the oil age will not happen because we ran out of oil. And it will not be a sudden or terrible shock that will bring economic hardship to people. The end of the oil era will be gradual, cyclical, and will open a new and more prosperous era for humans.

And it may be closer than many people think.

The spirit of peak oil

Peak oil theory is not that exciting in itself. The theory tries to estimate the point in time when production will peak, never to rise again, and puts energy to blame for almost any crisis and economic downturn. Many smart men have predicted the peak and failed. Many more will also try.

In addition to the numerous “fatalist” and “gloomy” conclusions that peak oil supporters derive from their analyses, perhaps one of the most relevant is “oil prices will continue to rise forever”. Not true.

As I set out to “debunk” the peak oil theory and its faulty conclusions, I have chosen the format of the main “realities and myths” used by peak oil defenders, which show the dangerous mix of misinformation and shortcomings in their thought processes to reach the wrong conclusions.

No better place to start than taking a look the historical context of the theory and its evolution.

1. The historical perspective of peak oil

The combined threat of demographics and scarcity of resources is nothing new, as famously described by Thomas Malthus in the nineteenth century.

Another century later, in 1956, M. King Hubbert introduced the “theory of peak oil”, which predicted that US oil production would peak in the early 1970s and decline thereafter, never to rise again.

The analysis was based on the then prevailing “limits of exploitability, technology, and market pressures”.

But reality has turned out to be quite different from what Malthus and Hubbert predicted.

Not only has global production risen, and US oil production almost back above the 1970s record, but it is expected to continue to rise …and adjust as needed to address structural needs.22

Looking back, with the benefit of hindsight, it is easy to see why and where peak oil has gone wrong. The analysis missed the potential for new discoveries, new additions, and new technologies opening up known large unconventional resources, as well as the potential for conservation, substitution, and demand destruction, entirely missing key fundamental dynamics of the market, where “demand creates supply”, just like “supply supports demand”.

Looking ahead, the exact same forces will continue to push the boundaries of peak oil forward, just like they have done in the past.

The “known unknowns” (such as new discoveries, additions, efficiency, and demand destruction) and the “unknown unknowns” (such as new technologies, geopolitical conflicts, and natural disasters), while impossible to predict, cannot be ignored.

2. The peak oil mindset

In the summer of 2008, during an Energy Conference in London I asked my audience “Who thinks oil will be above $300/bbl in 10 years' time?” Crude oil was making fresh new highs around $140/bbl and, not surprisingly, more than half of the audience raised their hand.

“And between $200/bbl and $300/bbl?” I asked. And quite a few more people followed.

And repeated the process with lower and lower ranges until I finally asked: “Anyone below $50/bbl?”…And the audience laughed!

I did not have a firm target price in my head, but I was very aware of the strain high commodity prices were putting on the global economy. In addition to $140/bbl oil, natural gas and coal were also making historical highs around $15/MMbtu and $130/Mt (metric ton), respectively.

My colleague and good friend Francisco Blanch, head of commodities research at Merrill Lynch, was paying close attention to the percentage share of energy to the overall nominal GDP in US dollars. In simple terms, the model showed that the global economy had limits. If energy as a share of the economy became too large or too small, the global economy would collapse, and determined a “sustainable” share of energy between 3% and 10%.

In 1998, energy became just 3% of the overall economy.23 The Asian crisis had sent oil prices towards $10/bbl and coal and natural gas prices were very depressed too. Oil-producing nations such as Russia were under severe pressure and eventually “cracked”, resulting in the Russian moratorium. The energy producer industry was breaking down. Such low prices were unsustainable.

In the 1970s, energy surpassed 10% of the overall economy.24 The oil shocks had quadrupled oil prices. The “energy bill” was too large, and consuming countries around the world suffered from inflation and weak growth through the 1980s. The energy consumer industry was breaking down. Such high prices were unsustainable.

But there we were, in 2008, with a share of energy around 12% surpassing the levels of the oil shocks of the 1970s. The situation looked unsustainable, yet, at that time, many reputable analysts were calling for “$200/bbl”. They, like many others, were caught up by the momentum of the strong demand from emerging markets. It was easy to lose perspective of the impact that energy markets had on the overall economy. But the model challenged the view. If oil prices rose towards $200/bbl, and natural gas and coal also continued their trend, the situation would “make the 1970s look like a walk in the park”, as Francisco used to say. Yes, it was impossible to predict the exact top of the market, but we knew the dynamics were unsustainable.

The model had many other valuable insights. For example, it was able to identify the channel of adjustments required in order for the world's economy to sustain $200/bbl without falling apart (that is, remain at 10% of nominal GDP in US dollars).25 One path was via sharp dollar devaluation. Another path was a larger global GDP. And another path was inflation. All perfectly plausible, but any of those would take years. There and then, in the short run, something had to give. Either prices went down, or the economy would “crack”. Or both!

The dynamics described above should not be confused with the “peak oil” view that the economy collapses as demand grows. The dynamic is a simple price–response situation, as in any other cost in an input–output world. When costs rise beyond reasonable, the economy responds by slowing down. It has nothing to do with depletion. At that time inventories were at the top end of the five-year average. Supply growth exceeded demand. The distorting factor? A $581 billion stimulus plan from China and growth in money supply of 13% per annum driving currencies, and the US dollar in particular, much lower.26

So, when I raised my hand, supporting $50/bbl within 10 years, many people thought I was joking.

“That's impossible”, someone said. In November 2014, with oil falling to four-year lows, this opinion would have been very different.

I was not surprised by the audience's reaction. At that time, $50/bbl seemed extremely low. Demand growth from emerging markets seemed unstoppable. Several theories had emerged that supported the bull case for demand and prices. Just a few years earlier, in 2001, Jim O'Neill, the then head of research at Goldman Sachs, had coined the term “BRIC” (in reference to Brazil, Russia, India, and China) in a report called “Building Better Economic BRICs” and looked at the new dynamics of the world by 2050. And a few years after that, my friend Jeff Currie published “The Revenge of the Old Economy”, which identified the bottlenecks on the supply side of commodity markets. And, of course, peak oil was peaking. All these reports reinforced the view that super-cyclical demand and supply forces were converging.

But the reaction also made me realize, in puzzlement, how short term our human memory can be. Just nine years before, in 1999, oil had reached $10/bbl. Just five years before, in 2003, we were comfortably trading at $30/bbl. And in 2005, half of the world was outraged when a Goldman Sachs analyst raised the possibility of a $105/bbl “super-spike”.27 Yet, in 2008, $140/bbl seemed a “stepping stone” towards $200/bbl, and the majority of the audience saw $300/bbl as the most likely scenario for oil prices in 10 years' time.28 Amazing.

But within just few months, by September 2008, Lehman Brothers collapsed. Global excess of credit, which had been wrongly perceived as “sustainable growth”, was suddenly evident in all corners of the world. The term “total debt” (public and private) became fashionable.

That is when many analysts woke up to the fact that global GDP demand and growth had been built on an enormous bubble of debt.

And when the credit bubble burst, the “unthinkable” happened. The demand shock arrived and prices collapsed towards $30/bbl within a few months. They did not stay there for long, as OPEC cut production aggressively and tightened the market, but showed that in the markets, just like the movies, “reality always beats fiction”.

3. Will global population, economic growth, oil demand, and oil prices rise “forever”?

While most of the peak oil arguments are based on “supply-side” issues, another key pillar of the theory is based on demand.

It is an undeniable truth that the global population is growing, and there is an implicit assumption that energy demand will grow with it.

Yet, the energy intensity of growth and efficiency are also at play, and are key in debunking the peak oil myth.

The argument goes like this: “The United States consumes almost 25 barrels per capita per year. China does not reach 5 barrels per capita per year. If China develops and consumes as much as the United States, we will have a supply shock”.

But this argument fails to recognize that peak oil demand is very real. Despite the growth in population, wealth, and economic output, the global oil usage per person per year has remained boringly stable since 1985 due to the impact of efficiency and technology. While industrialization reaches its maximum level of needed capacity, oil consumption declines.

The United States, the Euro-zone, and Japan are already past peak oil demand. In absolute terms, they consume less today that they did before. The peak in oil consumption in these regions happened in 2005.

The compounded result of slower growth rates in population, changes in the demographic structure, and changes in energy consumption per capita are likely to result in continued growth in absolute levels of demand, but growing at a slower and slower pace.

However, predicting global population growth, economic activity, and energy consumption are extremely difficult challenges, and are very sensitive to key variables such as fertility and mortality.

Yet, it is precisely because of the optimistic assumptions about demand that the world tends to develop protective cushions of excess capacity, both as a combination of centralized government planning as well as reacting to the super-cyclical market forces.

Converting those into price forecasts is even harder, as demand interacts with the supply. And, as we look at the future, the range of possible prices seems much wider than ever before. Even industry experts are diverging dramatically about the path and direction of prices.

4. Depletion vs. replacement: “Are decline rates accelerating?”

Another typical argument is “every barrel of oil that is extracted and consumed means one less barrel in reserves, so we must be running out of oil, right?”

Well, to start, it is worth clarifying that “peak oil” is often confused with oil “depletion”. Peak oil is the point of maximum production, while depletion refers to a period of falling reserves and supply.

Depletion of fields is a reality, a fact. Every barrel of oil that is extracted and consumed means one less barrel available for future consumption. There is no “recycling” of fossil fuels. Once consumed, they are “gone”.

Declines in production are normal and to be expected. As of today, 60% of world oil production declines between 1.5% to 2.5% annually,29 far more stable and lower than the 5% to 6% decrease that some peak oil defenders argue, thanks to enhanced recovery and advanced technology across horizontal drilling or deep-water.

But the fact that oil fields face depletion and decline rates does not imply a fatalist view of the world.

Replacement of reserves and production levels is not easy. It requires investment, and has often been slowed down by environmental and geopolitical issues. Yet, on average, the oil industry has invested around $750 billion a year, which has led to new discoveries and +100% reserve replacement.30

5. Will oil production fall abruptly and unexpectedly?

No. The main issue of production is not geology, as the late Christophe de Margerie (ex CEO of Total, one of the greats of the industry) or Rex Tillerson (CEO of Exxon) say over and over again. The main issue is geopolitical. The world could produce 90–92 million barrels per day today, if it wanted.

Exxon, which is well known for being prudent and conservative, sees steady growth between 2010 and 2040 in global oil and gas supply: +5.3% pa (unconventional), +4.8% pa (heavy/oil sands), +3.5% pa (LNG), +2.8% pa (deep-water), and +0.3% pa (conventional). No sign of peaking in any of them.31

According to Goldman Sachs research, there are more than 125 projects in OPEC alone that will be adding between 3.8 and 6 barrels per day 32 to supply in the short term that are just waiting to go on execution pipeline after receiving final investment decision (FID). The constraint is not projects, but project execution and human resources (engineers and capex) to develop them.

The global stated recoverable oil reserves, including conventional and unconventional sources, total 1.65 trillion barrels, or 54 years of supply.33 Those 54 years improve notably when we include efficiency and technological revolutions like …shale oil!

6. EROEI: Does it take more and more energy to produce energy?

So long as oil is used as a source of energy, when the energy cost of recovering a barrel of oil becomes greater than the energy content of the oil, production will cease no matter what the monetary price may be.34

M. King Hubbert

The energy return on energy invested (EROEI) is commonly used as the ratio of the amount of usable energy acquired from a particular energy resource, to the amount of energy expended to obtain that energy resource. The EROEI ratio has no units. It represents “energy divided by energy”.

Unconventional and new technologies fall towards the bottom end of the spectrum, which is used by many peak oil defenders as a problem.

However, they miss the key consideration that EROEI needs to be attached to profitability. A ratio of energy to energy without any economics is not enough.

Furthermore, EROEI is a dynamic ratio. Not static. Shell's analysis of oil sands production shows that energy used per unit produced falls dramatically over time across virtually all industry projects. The EROEI theory takes an individual projection (and this is typical for peak oil), leaves the negative elements untouched and stable (as if technology and resource development do not improve) and then expands it to the entire base. This, obviously, leads to a massive generalization and a leap of faith that can be easily denied just by looking at 20-F filings, that is detailed analyses per project, which are available to all shareholders in strategy presentations and fact books, where the undeniable fact that the oil sector's electricity and gas consumption has been falling while productivity, particularly in nonconventionals, has soared.

Since 1978 peak oil defenders have incorrectly estimated the decline in both production and reserves almost every year. Using EROEI is a very common excuse, and turning the debate to its alleged unsustainability is an incorrect justification.

7. “Are reserves being overestimated by the producers?”

In his famous book, Twilight in the Desert: The Coming Saudi Oil Shock and the World Economy (2005), Matthew Simmons, an investment banker, wrote that Saudi Arabia was running out of oil, and that no one would be prepared to deal with the impact. A highly controversial argument that gained a lot of supporters during the bull market, and almost 10 years after, the market remains very well supplied and Saudi Arabian production well above 2005 levels.

Some analysts say that OPEC-stated reserves skyrocketed from 878 billion barrels to 1.2 trillion barrels throughout the 1980s and 1990s, without any new significant discoveries being made. Is this correct? No. Analysts forget the additions from heavy crude that become commercial as extraction techniques and costs improve. This explains the additions of Iran and Venezuela perfectly, and the fact that international companies are interested in developing reserves in these countries proves the hydrocarbons are there.

But it is true that there is little incentive for producers such as Saudi Arabia to aggressively pursue exploration at this point in time. There is plenty to support demand growth. Production is at record levels. Some producing countries, such as Russia, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia, have combined short-term spare production capacity of 3.5 barrels per day to help them mitigate the impact of potential supply disruptions.

Other producing countries that produce at full capacity, such as Brazil and the United States, are expected to grow their output by 8% pa from current levels, with a potential acceleration from US shale oil.

As Christophe de Margerie, ex-CEO of Total, said in the Oil & Money Conference in 2012, “We have all the oil and gas we need. Apologies to those who want us to be running out”.

No peak gas either

Jumpin' Jack Flash, it's a gas, gas, gas

Mick Jagger/Keith Richards

As I commented before, in 1991 when I joined the oil industry, a friend asked me “Why are you doing this? There are barely 40 years of reserves left”. He obviously was wrong. A few years later, when I joined a gas transportation company, I was not surprised to hear him say “Why are you doing this? With renewables there is no future for gas. Everything will be powered by solar and wind by 2015”.

At that time, natural gas was largely viewed as a byproduct of oil extraction. Whenever possible, it would be consumed locally or transported via pipeline, but often the associated gas was simply burnt (flared) without any environmental consideration. It was more convenient to burn it than do anything productive with it. That's how bad it was.

But the LNG revolution made it easily transportable and quickly monetizable, and although it required large capital expenditure and knowhow, it opened markets for gas that would otherwise be stranded.

Today, natural gas is at the epicentre of the energy markets, clean and abundant, well positioned to expand on power generation and break into transportation fuels, challenging the monopoly of crude oil and OPEC.

Gas formulas: “Water at Coca-Cola prices”

New pipelines and LNG infrastructure projects are very capital-intensive businesses.

Consumers and producers had a “mutual interest” to build and develop the necessary infrastructure and in most cases would join forces and shared the risks by sharing the ownership of assets and financial risks though long-term commitments of often 20 or 30 years.

Long-term “take or pay” agreements ensured the gas would change hands, but at what price?

Fixing the price for 20 or 30 years was too risky. What if prices collapsed? And what if prices exploded? The party who had bought or sold at a fixed price would have a large financial loss or gain.

The solution required a “floating pricing” mechanism to ensure that contracts would be in line with the then prevailing market conditions.

But the problem was that there was no available benchmark for spot LNG cargoes. There were reliable reference prices for deliveries into Henry Hub (HH) in North America or the National Balancing Point (NBP) in the UK, but these prices reflected domestic supply and demand conditions in the US and UK, respectively, not Japan or Germany. And the difference could be very significant.

The solution was to create a “gas formula” that would link the price of natural gas to alternative substitute fuels.

Japan adopted formulas based on the Japanese Crude Cocktail (JCC), which once upon a time, before the oil weapon was unleashed in 1973 and 1979, competed with natural gas as feedstock for power generation.35

Europe adopted formulas based on crude oil, products, coal, inflation, and any other relevant factors. To protect both buyers and sellers against extreme divergences, the gas formulas often incorporated an “S curve” mechanism, a cap and a floor, so that the realized prices would stay within a reasonable and agreed upon range.

The formulas were then “calibrated” via coefficients. For the sake of argument, a simple formula where LNG = 0.1 × JCC meant that if the Japanese crude cocktail was $30/bbl, then LNG would be $3/MMBtu. The calibration was such that the prices on “day one” would be in line with the then prevailing market conditions.

For example, using the above formula if JCC prices increased towards $100/bbl, then the price of LNG would be $10/MMBtu, irrespective of where HH or NBP were trading.

Over the years, the gas formulas have been increasingly using other gas benchmarks, such as HH or NBP, looking to reduce the basis between LNG and crude oil, refined products, and coal. But these formulas are not perfect either. The way to minimize the basis risk was to create a proper benchmark for imported gas prices.

In practical terms, the gas formulas meant that the buyers were receiving physical natural gas but paying a price linked to oil. This created a significant risk that not many consumers were aware of, that is they were effectively paying for gas at crude oil prices.

Finally an Asian benchmark

In February 2009, Platts launched the JKM (Japan Korea Marker), an index based on daily assessments of LNG cargoes into Japan and Korea, the largest LNG importers in the world.36

The JKM benchmark is an important development for the LNG market, increasing the transparency and liquidity and reducing the basis risks, as Asia already contributes 55% of the LNG world trade.37

Let's buy Africa!

Large consumers like the UK or the US have benefited from large domestic resources and production. China is also one of the largest producers of most commodities, but unfortunately is an even larger consumer, making it very dependent on imports. For Japan it is even worse, as its domestic production is virtually non-existent.

Both Japan and China have taken an interesting approach towards energy security. Both have been aggressive in the acquisition of natural resources assets. The rationale is a combination of factors.

First, economics. Buying natural resources at the right time of the cycle can be an extremely rewarding business. Producers tend to suffer from the triple whammy of lower prices, lower volumes, and expensive financing. A great combination for anyone with cash and hungry for resources.

Second, financial risk management. Buying these resources reduces the exposure towards higher commodity prices. The profit on these reserves helps offset the losses. As a country, it may become a “zero sum game” controlled by the government, which can help subsidize consumers through other indirect ways.

Third, physical risk management. By controlling those assets, it can also control the off-take of the physical flows. They help “vertically integrate” the exposure, from the production to other added value processes such as refining of oil or metals.

But these investments are subject to local laws, local taxes, and the risk of expropriation and nationalization. No wonder China and Japan have a strong preference for countries like Australia. But the value and their cash is more needed in other remote and perhaps riskier countries. Look at Myanmar for example. And neither China nor Japan are “shy” to expand to their reach to new markets across Africa or Asia.

In addition to the size, most of the reserves in sub-Saharan Africa are accessible to international investors, in contrast with some other regions of the world. While oil reserves are diversified across the continent, proved gas reserves are still largely dominated by Nigeria, although potential future gas-producing provinces are being discovered elsewhere as the emergence of export and local markets for gas in Africa should provide incentives for gas exploration and increase further proved African gas reserves in coming years.

The growth of proved oil and gas reserves in sub-Saharan Africa in the past 30 years has resulted in the growing importance of Africa as a major world hydrocarbon producer. Africa has consistently gained market share of the world hydrocarbon supply.

Currently 25% of US oil imports and 30% of Chinese oil imports are sourced from Africa, and those proportions are expected to increase in the future. More than $120 billion have been earmarked for investments in resources in the African continent in the past years.

These investments are increasing the cultural exchange, with the Chinese and Japanese becoming more integrated within the host countries. Who knows, Africa in 50 years' time may look a lot like Brazil today, a wonderful mix of races and cultures.