Over the course of all the visits with classrooms, I heard a lot of words. Through it all, there was one that stood out. It’s a word I heard many times from more than one educator and one I’ve tried to make part of my daily vocabulary. The first time was when the teacher thoughtfully interrupted a student who was talking. The student had just told me that he couldn’t play any instruments.

“Yet,” the teacher interrupted. “You can’t play any instruments . . . yet.”

It was a small moment between teacher and student, but a big lesson I needed to hear. Three letters making up one very small little word. Yet can change how we think about ourselves and all that is possible. Who we are today does not have to be who we are tomorrow. We are not the grownups we can be . . . yet.

I learned that many schools were incorporating the idea of a growth mindset. The term comes from professor and researcher Carol Dweck, whose studies in the psychology of motivation and success revealed the massive significance found in how we frame our abilities. A person can go through life with a fixed mindset, thinking they are forever only capable of what they can do now. Many people do this, but they’re stuck. With a growth mindset, there’s no end to what someone might be able to do. It’s the idea that we can always be learning and advancing, in every area of our lives. A tough patch is not an automatic failure; it’s a challenge. We just have to be willing to grow.

While some people might dismiss it as a mere buzzword, a growth mindset goes beyond being a trend. Many educators have altered their approach to all their work because of it. Schools have always strived to be places where people grow, but Dweck’s work has prompted many to create cultures and environments where students are passionate about stretching and growing, forever. One principal described it as an attempt to create “lifelong learners beyond the classroom.” The idea definitely began to have an effect on me.

I was reminded of how terrifying school could be at times. Trying something new, and knowing there are people watching—classmates you want to impress—well, that can be mortifying. You want to look smart! I wondered if maybe all these educators remembered just how uncomfortable it is to take that risk. While so many other grownups might have forgotten what school could be like, these teachers were creating safe spaces for students to say, “I don’t know.” And as these students said this, the teachers were all gently adding, “. . . yet. You don’t know this yet.”

One teacher told me his fear of failure is actually what led him to a career working with students. Describing himself from early elementary school until junior high, he said, “I was so afraid of messing things up. I wanted everything to be perfect.” Mr. Paul, as the students call him now, worked to have perfect penmanship, perfect report cards, and even perfect attendance. However, in junior high, a science teacher changed the way he thought about school forever.

“This teacher divided us into groups. He passed around all these different experiments we had to do together. Then he stood at the front of the class and watched with glee as every single one of them failed.”

The teacher had purposely given them all instructions for experiments that would not succeed.

“I remember being on the verge of tears. I’d followed his steps word for word. I did everything exactly as it should’ve been done, and it was a disaster—a glorious disaster.”

Now, “glorious disasters” are a key part of what he does. Like his mad scientist teacher before him, Mr. Paul begins each school year by setting his students up for experiments that will fail. While that might sound sadistic, he knows what a gift failure was for him when he was a student. Failing, done correctly, is learning. The students begin questioning instructions they’re given, they gain an understanding of how experiments work, and they gain a bold new spirit of curiosity about what might happen next.

I’ve spent a lot of time in my life worried about what might happen next, especially recently. Following the viral success of the pep talk, I’d become petrified of making any further moves for fear that one of them might be the wrong one. A failed experiment in a classroom is one thing, but the stakes were higher here in grownup land. A fruitless business venture or an unsuccessful creative endeavor could have far-reaching consequences, not just for me but also for my family.

The weight of all of this, mixed with exhaustion and a deep depression I’d never known before, had pulled me down to a place that I didn’t think I’d ever find my way out of. It was a dark, scary place where, for lack of any other decision-making abilities, I ate way too many Oreos.

Now, on the other side of that, I can see all that I’ve learned and all the ways that I’ve grown. It’s just . . . growing isn’t always fun. It’s actually really painful most of the time.

Mr. Paul’s classroom, like many others I visited, was lined with posters encouraging students to be inspired by the examples of famous failures. Images of brilliant minds like Albert Einstein with words about how he wasn’t a great student, or a poster of Harry Potter author J. K. Rowling sharing that her manuscript was rejected twelve times. They’d both done okay for themselves. I’d heard those stories before, but I wondered if Albert Einstein or J. K. Rowling ever ate way too many Oreos. I was certain my unique ability to fail spectacularly and make poor decisions far outweighed their talents as famous failures.

Mari Andrew is an illustrator and a friend who shared something I think about all the time. She opened up about a family friend who had died the week before. She said so many people talked about him in big, beautiful ways. She wrote this: “People described him as the ‘most compassionate human of all time.’ I’m blown away by that legacy. This morning I’m thinking about how I want to be remembered and working backwards.”

I was pretty far into my listening project and had focused solely on kids. It’d been life-giving to hear their perspectives, and they’d brought me back to seeing the world with childlike eyes. Over and over I’d heard thoughts from them about how I could be a better grownup and, until now, I hadn’t thought to interview any people who’d actually grown up.

So I wondered if I could do a little experiment. I’d begin to interview a few older people, adding them into the Listening Tour. Specifically, of course, people who didn’t make aging look miserable. I’d seek out a few men and women who’d grown and aged gracefully, make notes on what I wanted to implement from their lives, and, if my experiment wasn’t a disaster, from there I could just . . . work backward.

As I started this new phase, I also had to come face-to-face with something: I didn’t know or spend much time with many people who were much older than myself. This was due to a slight fear, maybe. You don’t want to bother people who are older. They’re busy doing older-people things. I also didn’t know what to talk about. The biggest reason, though, had to be that I didn’t want to do or say anything wrong. I guess, even though I’m an adult now, some part of me still has a fear of getting in trouble.

Walker had never made me feel this way. I decided he’d be the perfect person to start with for a number of reasons. Number one, I know him and he knows me. My wife and I were friends with him and had worked at camp with some of his grandkids. Now we lived in the same town, and he always made a point to check in and see what I was working on or how things were going with me. It always surprised me that he even knew my name.

My friend Walker Whittle is a veteran of World War II, well into his nineties, a retired business professor, and an incredibly active member of our small community. I make silly videos on the internet. Sometimes unlikely friendships are the best kind.

A few weeks before I connected with him to be interviewed, he was trying to convince me to buy a giant ham. The ham was for a fundraiser he was organizing. Mr. Whittle was heavily involved in our local Civitans, a volunteer group dedicated to meeting and serving needs in communities around the world. This was just one of the many ways he stayed busy. He was committed to his deeply held faith and also very interested in cooking, traveling, and reading. Often our discussions were about whatever book he was reading at that time. He claimed to devour three books each week, and I believed him. His interests ranged from old baseball players to theology to history to whatever else he could get his hands on.

He’d seen many things in his ninety-five years. He had countless fascinating stories about his time in the service. One thing that always surprised me was the superb detail with which he could recall elements from his time in World War II to his time teaching, including particular students, names, and situations. He could even still tell vivid stories about his days as a child. When I arranged to meet up with him, I let him know this project was about my attempting to gain wisdom from listening to kids and, now, former kids. He came prepared with a list.

So these are the “chapters of life.” He smiled as he shared them, but there was also great caution in his voice. It was as if he’d seen many people go through this life adventure, himself among them. These few words he’d typed out were the result of lots of experience.

THE CHAPTERS OF LIFE

(according to Mr. Whittle, age 95½)

Infancy: A period of innocence

Youth: A period of discovery

13–19: A period of uncertainty, yet decision

20–30: A period of direction and wonder

30–40: A period of production and expectation

40–70: A period of regret or rejoicing

70 and beyond: A period of satisfaction and seeking

At first, I was thrilled. Here I was wanting my life to be my Space Jam, and he was outlining all the chapters for me. These chapters, however, didn’t exactly sound thrilling. Easier, calmer chapters would’ve been nice. You know, chapters where it’s me not having to do anything, people just bringing me really good food, and everything always working out for the best. The end!

Curious, I dug a bit more. “So, all the chapters are already determined? I don’t get to choose what happens? Am I stuck with these?” I asked.

“Each chapter has choices,” he said with a grin.

“But what about the things that happen that are completely out of my control?” I asked, as if I was actually going to stump a ninety-five-year-old man.

“There’s parts of the story you don’t get to choose,” he again said with that smile. “But you do get to decide how you’ll respond. Those decisions shape every chapter after that.”

Decisions. Sometimes even just deciding what my wife and I will eat for dinner can send me in a panic. To my ears, decision is a scary word like ax murderer or clown or incoming call. My decision aversion has upset my wife on plenty of occasions. In fact, I rarely call anyone on my phone—even her. It’s as if I’m constantly afraid my decision to call will create some catastrophic chain of events or, worse, bother someone.

I don’t want to be a bother. I don’t want to be bothered. I don’t want to make a decision that might bother me, someone else, or the universe at large. Decisions have consequences and I don’t want consequences.

But again and again, decisions would come up in every conversation I had with any older friends I spoke with. Starting with Walker, they’d all talk about good decisions and bad decisions. These decisions have really stuck with them, too. Some decisions, as Walker suggested, result in great rejoicing; and some, in deep, painful regret.

“But what if I make the wrong choice? Mr. Walker, what if I fail?” I asked him.

“Don’t worry,” he told me. “You will fail.”

Not exactly the encouraging words I’d been hoping to hear from my older, wiser friend. Didn’t he know I was the pep talk guy? I write pep talks. I need pep talks. This was not a pep talk. However, he knew I needed it, and he knew I could handle it. Failure is inevitable. Failure, done correctly, is learning. It’s growing. Deal with it, kid.

He told me his pro-failing stance is one of the things that’s helped him grow and one of the things he continually tries to instill in his children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

“Keep trying and learning. Failure is part of the process. It means you’re living.”

So, failing means I’m living. To a degree, that’s freeing to hear. It means I’m pretty alive at the moment. It’s okay to mess up. It’s part of the process. But these decisions have weight. There are consequences, right? Walker’s chapters-of-life breakdown even outlines it.

“So, thirty years of regret or rejoicing, huh?” I asked.

“Well, it’s obviously different for each person, but I’ve found it to be true,” he said, pausing to add an important disclaimer. “Good news, though: You can also start over at any time!”

“There are do-overs?!” I excitedly asked.

“Yes. There are do-overs.”

Discussing fears and dreams with elementary school students could sometimes remind me how much weight our choices have even at a young age. Sometimes students brought up issues and troubles I’d forgotten were part of being a child. “I used to sit alone at lunch,” shared one boy named Jarrett. He had a strength and a sadness in his eyes as he added, “but now I have some friends here and I’ve been nicer. So that’s good.” It sounds like he’s getting a do-over, but it was so tough to hear this kid open up about his trouble making and keeping friends. “I’ve been nicer,” he said. That’s the part that killed me. He’s trying, really trying. He spoke like he was making progress, but I could hear in his voice and see by his classmates’ reactions that he likely had lots of difficult days ahead of him. He still had some junk to figure out. It brought back every remembrance I ever had of feeling not up to the task of being a good-enough person even to sit by someone or deserve a friend. I’d felt like Jarrett before.

Our memories are sometimes short, and we can easily forget how difficult growing can be. We have these colorful recollections of the fun and freedom of it all but sometimes draw a blank when it comes to the frustrations found in that time of figuring life out. Unprompted in every listening session would be words from some fragile student that reminded me of the confusion and terror of being young: “I’m afraid everyone will laugh at me.” “My parents don’t let me do anything.” “I wish I were better at tests.” “Nobody understands me.” They shared bewilderment and doubt, much in the same way any human of any age would, simply at how to get around in this world as a person.

In video games when you “level up,” you become something new. You’re the same character, be it Mario or Princess Toadstool or whoever, except you’ve leveled up. This means you’re bigger now. You have more powers. Sometimes leveling up also means you get cool stuff. You’re the same person, but now . . . you can do more. This idea is not only exciting; it’s also thrilling to watch. The moment you level up in a video game is full of triumphant music and graphics. Time stops. Your character usually freezes in the air, surrounded by flashes of light. All is as it should be . . . in the game, at least.

In real life, true growth isn’t glamorous. It’s gritty. It doesn’t happen in an instant. True leveling up requires patience and effort. It’s much more than just pushing the right combination of buttons.

So often the metaphor of a caterpillar becoming a butterfly is used when talking about our growth and development. For me, though, this story has perpetuated the idea that we would enter adulthood and be done. I’ve had this false expectation that I’d become a grownup all at once. I’d arrive fully formed and ready to flutter through the sky in all my butterfly glory.

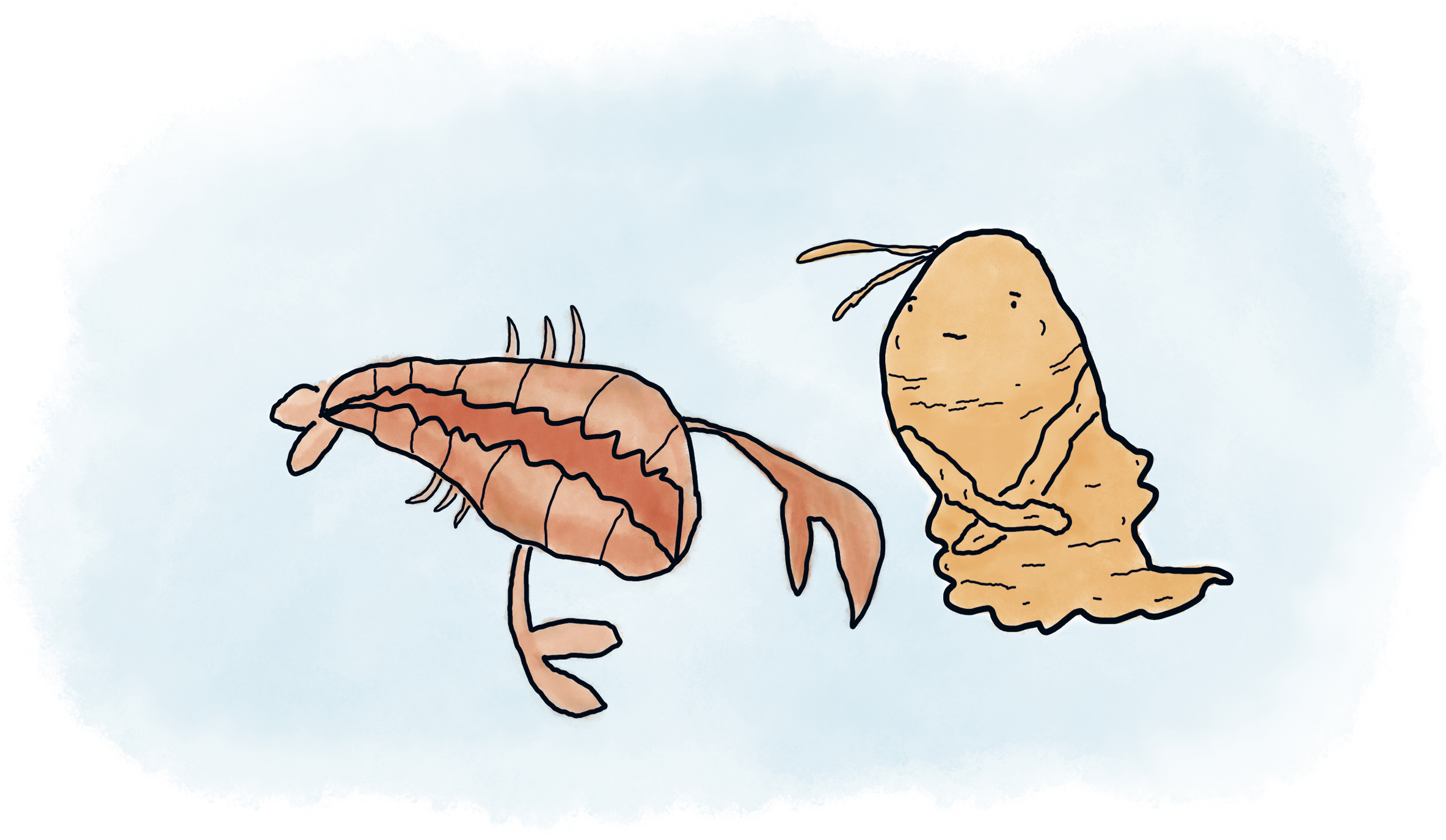

Lately, though, I’ve been thinking a lot about lobsters. I’d seen people pass around an image online claiming that lobsters could live forever. The information was presented as if it were common knowledge, but it was totally new to me. As someone with a great interest in living forever, I began to inquire further.

What I found out is this: Lobsters are not immortal. They do, however, age in a very different way from how we and most any other animal age. Unlike people, lobsters don’t really slow down as they get older. They keep growing and growing until they die. (Either from natural causes or a predator or a freak boat accident in which the lobster steals a boat and realizes it cannot drive.)

So how do lobsters do this? Well, they grow by molting, but specifically from something called ecdysis. Ecdysis—which is Greek for “putting off”—is the art of escaping their old shell. In order to grow, the lobster’s shell must be put away so it can grow a new one. Sounds simple enough, right?

Every lobster could stay as it is, but that would mean death. Imagine the pressure the lobster must feel, being bigger on the inside than their outer shell can contain. The lobster begins to break their shell and then must complete the harrowing process of crawling out of it. The process leaves the lobster exhausted and exposed. This is an extremely dangerous time for our lobster friend. It is at extreme risk of infection or being eaten. For protection, the lobster hides in a dark place as it rests and heals, waiting for its new shell to grow.

Then, one day, everything is different. Our brave lobster has a shiny new shell. It emerges back into the busy life of the ocean, bigger and stronger than before—at least until it grows out of the newer shell and must go through this entire process all over again. And again. And again. And again.

Lobsters are in a constant state of growth. On average, a lobster goes through the molting process forty-four times before its first birthday. Then it gets in a rhythm of doing this once every few years. For lobsters, life is the perpetual process of becoming new. They spend most of their time either preparing for shedding their old shell or recovering from it. Preparing for growth or healing from growth—that’s their life. Maybe, if we’re doing it right, that’s our life, too.

As if that weren’t shocking enough to discover, the lobsters aren’t precious about their old shells, either. Do you know what they do with them? They eat them. They use the old shell for nourishment as they heal and the new shell hardens. Maybe instead of being nostalgic about all our past pains and successes, or in lieu of carrying them around with us, we could let them all become fuel for our journey. We’re best served by carrying only more wisdom and more strength into each future moment of our lives. Preparing for growth and healing for growth. That’s the secret. Of course, we can only do this if we choose to have the daring determination of a lobster.

Maybe this is why some people grow older with such a fixed mindset. They’re hard. They’re stuck, hampered, and cramped in the hard shell they refuse to shake off. I get it, though. It’s understandable. Growing into the fullness of who we are meant to be requires risk. It’s gross. It is not elegant. It’s hard. It takes everything we’ve got. We want to maintain our dignity and stick with what we know. But a refusal to grow is an offense to the natural way of things.

If you still have a pulse, you have a chance to grow. We’re all amateurs, rookies, apprentices, and beginners in some area of life. I’m learning how to keep growing and embrace it with a childlike enthusiasm, even if it makes me uncomfortable—especially if it makes me uncomfortable. This means feeling like you’re putting on new shoes that are a little too big, but that’s a good place to be. You’ll grow into them. Stumble around awkwardly in those floppy shoes. Learn how to move through life in those floppy shoes. Dance clumsily until they fit just right and it comes time to burst out of them and get new ones. Even if you don’t feel like you belong in them. Life is an ongoing experiment in realizing just how qualified you are for the position of you—how perfectly cast you are in the role of yourself. You’re just growing into it.

In one classroom I visited, a boy named Jameson, age nine, told me this:

“To be a grownup means to have a good life.”

I agree. A few months after my last conversation with him, Mr. Walker Whittle died. His death came as a shock to most all who knew him, even though he was ninety-six. The man was full of life until the very end.

Walker liked to make lists. He made grocery lists, book lists, and, most important, life lists. I’d collected many of his little sayings and quips of advice over the years but had forgotten about this list. When he passed away, I found myself returning to his words of wisdom and especially treasured one he called “Walker Whittle’s Life List (regarding wisdom and encouragement).” The list reflects his desire to live a life of service and of kindness. It speaks to his profound and personal faith, and it was a work in progress until he passed.

Walking into his memorial service, I carried with me his wisdom written on a few small sheets of paper. It was a true celebration of a life well lived with a standing-room-only crowd. As I made it through the line to see his family, I found his great-grandchildren. He was proud of them and had every reason to be. I hugged them and then handed each a little sheet of paper containing their great-grandfather’s “Life List.” Like the answers to some great test, it gave us something wonderful from which we could all work backward. An experiment that wouldn’t fail but that would lead to glorious growth. Again and again and again and again.

WALKER WHITTLE’S LIFE LIST

(REGARDING WISDOM and ENCOURAGEMENT)

-

DO NOT BE AFRAID.

-

TRUST.

-

PRAY FREQUENTLY. (You don’t have to be on your knees to pray.)

-

HAVE SOME VALUES that are UNCHANGEABLE.

-

RECOGNIZE your LIMITATIONS without STRESSING YOURSELF OUT.

-

TREAT YOUR FELLOW MAN LIKE YOU WOULD LIKE TO BE TREATED.

-

COMMEND and COMPLIMENT the SUCCESS of OTHERS.

-

DO FOR OTHERS WITHOUT EXPECTING ANYTHING in RETURN.

-

BE KIND and COURTEOUS.

-

LET the LIGHT be YOUR LIFE be YOUR ONLY LIVING.

* NONE of THESE ARE WORTHWHILE unless GOD is NUMBER 1.