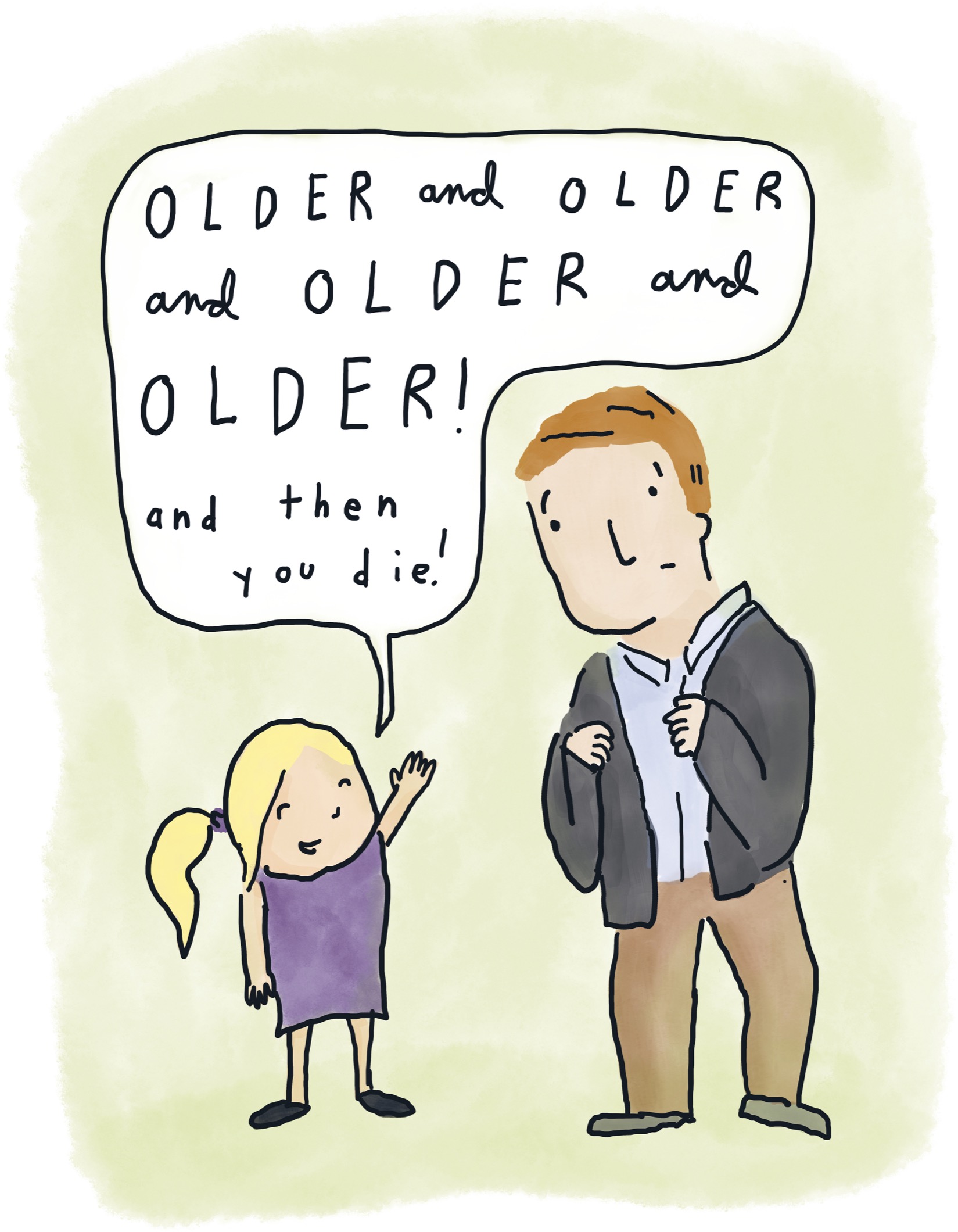

“You get older and older and older and older and then you die.” These were the words of Morgan, age eight. It seemed an especially dark perspective on life coming from a third grader. I found myself making the kind of face you make when you’ve just heard nails on a chalkboard. She had somehow captured all the agony and astonishment of the human condition in just a handful of words. All I’d done was ask, “What does it mean to grow up?” We get older and we get older and then pfffft the end. The entire classroom giggled. I winced.

It is true: Growing up is a fatal condition. Surely, though, there’s more to being alive than just getting older and older and then dying. This idea that aging is terrible, unavoidable, and leads only to death has been passed down from generation to generation. Much in the same way families pass down heirloom necklaces or prized handkerchiefs or heart disease, we pass down ideas of what it means to age. Advertisements promote products that promise they will “fight aging.” Filters for photos smooth out our skin, taking years off our complexions. We compliment older people by telling them they “look so young.” It makes sense that we want to stay stuck in adolescence. The alternative, marching unphotogenically to the grave, is not appealing.

Aside from Morgan’s morbid response, there were other insights. According to Sofia, “To be a grownup means to be eighteen and older,” the legal definition of being an adult in the United States. But the age students gave me for what it means to be a grownup varied from student to student and school to school. For some it was twenty and others eighty-five. They didn’t seem to have a clear handle on the precise number. According to one study done by the Marist Institute for Public Opinion, the students’ ideas about adulthood mirror another widespread source of confusion.* If you ask a baby boomer what old is, they’ll respond seventy-seven. If you ask someone from Generation X, they’ll respond seventy-one. If you ask a millennial, they’ll tell you sixty-two.

The same study found that when people were asked what age they hoped to live to, the average number was around ninety. We may all differ on what old is and have complicated ideas about what it looks like, but we are united by at least one thing: We’d all like to live long, happy lives. So, what is it that we’re all aging toward? Do we just live and start getting slower and more feeble until we can’t move? Do you just exist and keep existing until, as my third-grade friend and philosopher-queen Morgan, age eight, says, “you die?”

In spite of all this mystery and uncertainty, I’d found there were still lots of kids who couldn’t wait for their turn to grow older. Inspired by the Kid President concept, several students regularly shared with me what they would do if they were in charge of things. Some had a list. They had new rules they’d implement. These ranged from “Everybody should be nice to everybody” to “You should have to wear a Pokémon shirt on Mondays.” They had great things they would accomplish, like space travel, circus performing, and, one of my favorites, “taking the pictures of hamburgers that you see on menus.” Still others seemed to dread the day it’d be their turn. As a fifth grader memorably wrote to me, “I don’t want to grow up because then you have to clean up all the throw up.”

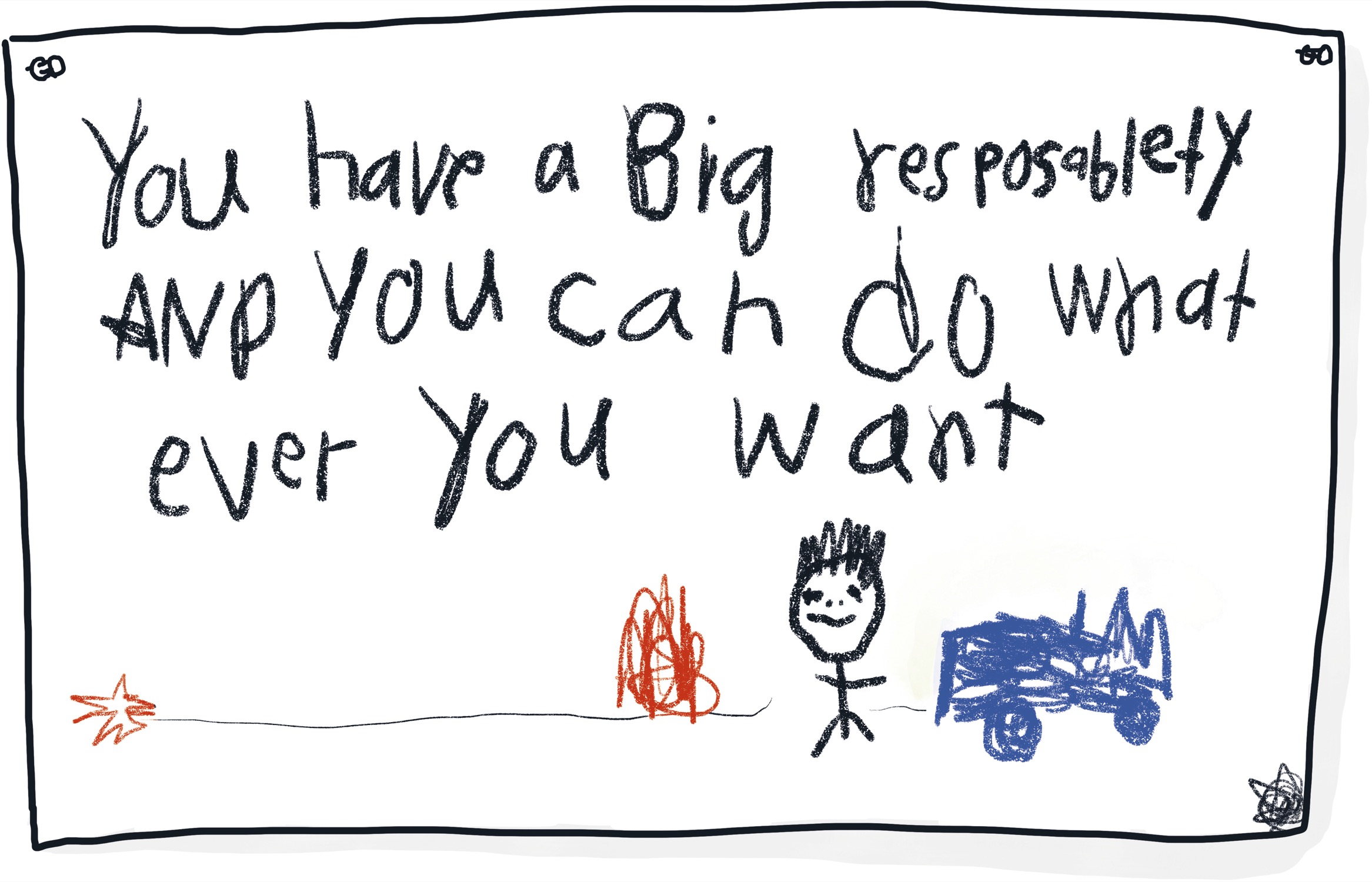

One student’s description of being a grownup earned a spot above my desk. I grabbed a thumbtack and stuck it there because something about it really spoke to me. Using colored pencils, he’d drawn a stick figure standing beside a car. Above this he’d written: “YOU HAVE A BIG RESPOSABLETY AND YOU CAN DO WHAT EVER YOU WANT.”

This was like one of those great motivational posters you’d see in an office or a classroom. Except this didn’t have a cat dangling from a limb with the words “Hang in there,” nor was it an eagle in flight with inspiring words about soaring or success. It was a scrappy little stick person standing next to a modestly drawn vehicle with a mixed message of blessing and burden. It was like this kid was giving me a reminder, but also permission. You can do whatever you want! He’d totally captured the freedom. You have a big responsibility. He’d also captured the weight. It’s burdens and blessings and it’s balancing it all. Yes, you can do whatever you want, but there’s also dishes to be done and throw up to be cleaned up.

I’d become more and more interested in seeing what older people had chosen to do with this freedom and responsibility. It came out of a budding curiosity and a deep need to see what I, myself, might be marching toward. It seemed to me more and more that aging was walking away from so many youthful things I’d held dear. As I put together my list, I worked to include men and women who’d grown up but still somehow held on to a childlike exuberance. One of these was a man I’d admired for a long time.

Michael is a storyteller and teacher who has, for decades, collected narratives from different cultures all over the world. I’d been encouraged by him for a long while and was interested in spending more time trying to understand how he thought about things. Recently, he’d been using his gifts to help young people dealing with depression, addiction, and anxiety. I knew there was a lot I could learn from his mentorship programs and classes, but I also knew deep down that being with him would be illuminating. Michael delivered immediately:

“Everybody is getting older. That’s not an accomplishment. The trick is to get elder.”

He’d seen many of his friends age. Of those, he explained, some had become better, some bitter, and some had morphed into what he described as “dangerous, angry children in grownup skin.” These were all versions of older people I’d known and seen. I’d also imagined myself growing into each of those various roles. Maybe one day I’d become a truly great old man who gave out candy and wisdom to every person he met. I could also see how dashed dreams and disappointments could, over time, fashion me into a closed-off curmudgeon. Becoming a dangerous, angry child in grownup skin was certainly not one of my goals, though. Thankfully, he pointed me toward something hopeful and truly aspirational.

There is a way to step into adulthood with awe and beauty. Michael shared with me what he’s learned about aging from his friend Malidoma Patrice Somé. Malidoma is an elder in the West African Dagara tribe. In this tradition, becoming an official elder of the tribe is not something you declare yourself. That’s not behavior befitting of an elder. Nor is it something you can campaign for. A true elder wouldn’t create promotional signs, bumper stickers, or Instagram posts. Being an elder is something you embody. You are then tapped on the shoulder when the time comes and asked to serve. There is even a song the tribe sings, which is a “call for elders.” It cries out that many of the oldest among them have died. Azi so na. Eze ma culi. Azi so na. Te semani. Ba de na. This translates roughly to “The world has gone wrong. Somebody take us home. The world has gone wrong. We’re losing our fathers.” It is an announcement that there is a great need. The time has come for those who are of age to accept responsibility not just for themselves but also for the direction of the entire tribe. Rise up, elders! Rise up!

As he described this to me, he softly sang the words of the song. I could feel every hair on my arms stand on end. The song holds a great sadness for the state of things but also a great hope for those who might accept the responsibility to lead everyone forward. This urgent plea would surely be delivered with a painful lump in each singer’s throat. It acknowledges all that is being lost around them while at the same time dreaming about what could be. This rallying cry seemed to articulate a deep-seated feeling I’d had within me but did not have the words for.

This is so vastly different from the way we handle aging in U.S. culture. I wondered how a call for elders might go over in my neighborhood. As someone who’d spent the last two years listening to children, I’d become more aware than ever of the deep need for loving grownups in every corner of the world. This was, finally, something challenging and exciting to march toward. Also, as a current grownup in progress, I, too, could use some older, wiser guides to rise up. Could I stand on my lawn and sing this song or maybe put an ad in the paper?

Our culture is pretty good at creating olders, but we don’t necessarily excel at raising up elders. I didn’t realize it when I started, but I think that was the impetus for this book. Sure, I felt unworthy of being called a grownup, but honestly, I didn’t really want to become one. I had no interest in getting older. Becoming a grownup meant I was a step closer to death. Maybe we need more people tapping us on the shoulders and inviting us into life, getting elder. That’s a journey I can be excited about.

There really aren’t any moments in our culture when we intentionally invite people to rise up. We have elections. We have graduations, birthday celebrations, and other moments when we mark a transition. Rarely, though, do we tell people in our community that we need their specific gifts and experience to be used in shaping and guiding the younger people around them.

It’s a big responsibility, and you can do whatever you want.

One of my favorite examples of seeing this kind of grownup began in a Boston, Massachusetts, classroom. The teacher, Catherine Epstein, discovered something troubling. She’d been struck by the way people online talked about those who were different from themselves, especially when it came to politics. Like many people, she’d grown tired of cable news and heated debates on social media. She originally thought these generalizations came only from more closed-minded people—you know, former kids, olders. However, she began to recognize that her young students were also already very interested in what was happening in the news. She noticed they, too, had similar ideas about current events and weren’t shy about sharing them. However, they did all seem to have similar takes and seemed to be very unaware of how anyone could ever see things differently.

Seeing the vitriol of public discourse all over the world and already noticing the seeds of it in her young students, she decided to do something. Catherine might not be able to change the whole world, but she could at least change her classroom. So that’s what she did. She started a pen pal program. The idea was to connect her city-dwelling, largely left-leaning students with a group of kids in a very different environment. She found a classroom in Ozark, Arkansas, in what was described by their teacher, Cherese, as a “very rural, ultra-conservative public school.”

It’s not often that you start a relationship based on disagreement, but this experiment would challenge a lot about what they knew relationships to be. With this project, Catherine and her new, very different friend Cherese set out to show their students what it could look like to disagree beautifully—a course many grownups in the world could use. For me, following their journey changed the way I view friendships, disagreements, and connection forever.

Between the two schools, there was already the massive difference of place. As Catherine put it, “Just what they see outside their windows is different.” Beyond their geography, the way they view themselves and their happenings in it were drastically different, too. Catherine and Cherese set out to help guide their students through the many differences. They let them know who’d they be writing to. Each group immediately had assumptions about the other as the letter writing began. Off they went.

The first few months, students got to know one another. These letters were mini-biographies mixed with questions for their new, mostly unknown friends. They shared information about their communities and their homes, hobbies, and families. Many included drawings and details beyond the scope of what was asked—in doing so, adding human flourishes to what was, essentially, just a school project. The old-fashioned act of actually writing a letter was new to the students. It was a slower way of connecting than they were used to, causing them to reflect on their thoughts and making the letters a personal exploration as much as a cultural connection.

Both classes would wait eagerly for each new batch of letters. They became a key that unlocked conversations the students didn’t know they wanted to have and caused them to find words and feelings they didn’t know were inside them. As the letters progressed, students began confronting differences with prompts from their teachers. Difficult and divisive topics like race, religion, gender, and guns were incorporated into the discussions. These were the sorts of topics you might not want to talk about around a dinner table with immediate family, much less with strangers via letter. Yet they did. With their teachers as their guides, the students explored how to share and how to listen.

It took some work to find the right words, though. The two teachers felt their role was to show the students how to use what they called “helpful” words. The work became very much about creating constructive conversations, which meant that the students were not focused on proving themselves correct, being especially clever, or trying to convert their new friends to their perspective. Even with their own differences, these two educators formed a friendship based on their trust that this pen pal project would help their students gain a better understanding of themselves and people they disagreed with.

The project started out wonderfully, but something they didn’t plan for began to happen. When conversations became slightly heavy or seemed to be moving into a space that might threaten the warm, friendly nature of their earlier letters, the students would pull back. They’d return to discussing less divisive things like music and classwork and the weather. When I heard about this, I found it charming. Even with their strongly held beliefs and opinions, these students felt a very human need to preserve their new friendships. They longed for peace, and I found that beautiful and hopeful.

The teachers, though, were wiser than me and realized this wasn’t actually helping the students grow. They were no longer stretching or challenging their ideas. They were holding back. This would not result in developing empathy for someone who might see things differently. Instead, they were just ignoring their differences.

Uncomfortable as it might be, these teachers realized they’d need to push their students beyond avoidance. For most of their young lives, the examples they’d been shown of handling conflict were aggressive. They were examples of people attacking one another. The only other example they’d been shown was avoidance, which is what they’d all started emulating.

So these teachers and guides showed them a different way.

Catherine invited a friend to her class named John, an expert in disputes. To be clear, John doesn’t cause disputes but rather helps create conversations and resolutions around them. His team, Essential Partners, works to help people navigate conflict. To do that, they help people realize that we’re all essential partners in this life. The idea is to see the humanity in other people and engage with it. The key, he revealed to the students, was being clear that this was about investigation. Calling it an investigation helped frame the conversation for students in a way that allowed them to hang on to their friendships while also engaging with their differences.

Surprisingly, John’s approach wasn’t about finding common ground or persuading or even agreeing. It was about having genuine interest in each other. Each student would have to speak about where they were coming from and each student would agree that all other students were essential teammates on this planet with them. Seeing the humanity and engaging with it was the goal.

I got to spend some time with Catherine’s students. The effect the project had on them was visible almost immediately in how they interacted with me. It’s remarkable what can happen when you treat someone as “essential,” even if they’re just a strange guy doing a listening tour. They reflected on how the letter writing changed them along the way. One student told me, “I used to think of people as ‘other people’ or as ‘people that are wrong,’ but now I can talk to them. Now I see everyone as a person worth listening to.” The stories they’d believed about those who were different from them had been dismantled. Now they encountered real humans, with all their humanity, and couldn’t see them otherwise. Even if they disagreed.

They opened up about earlier assumptions they’d had and were often embarrassed at how small their eyes had been. There’s great humility required in admitting that. The students spoke of walking out of their classroom now feeling more accepting of others. It was the kind of feeling I want for my own children. It’s the sort of thing I want the whole world to know. I began to wish every human on the planet could somehow find themselves studying at the feet of Catherine and Cherese, two people embodying the role of elders right where they are, helping those in their midst find the humanity in everyone.

Thankfully, though, there are already teachers and guides, elders—not olders—all around us. People who are quietly and boldly showing the way forward. There’s no magic age when you step into this role. I found that many elders I’ve met are not, in fact, elderly. These are just people recognizing a need where they are and doing what they can to rise up to meet it. These people are not campaigning. These people are not trying to acquire power. They are simply rising up to help others rise.

During my time with Michael, I asked him what sorts of things he, as someone working to get elder and not older, tells young people. Many of the kids he works with have either attempted to take their own lives or are at great risk of doing so. He told me, “The amount of suicide amongst young people is partially because they think they’re worthless.” This overwhelming sense of worthlessness cannot be conquered without deep, meaningful relationships. So he begins by making certain they know this:

“The first thing I always say: ‘You don’t have to become someone; you already are someone.’”

As he said this, an unexpected wave of emotion came over me. I couldn’t explain it in that very moment, and I still struggle to understand it all. Somehow he’d tapped into wounds I hadn’t realized I’d been carrying around. My eyes filled with tears. His healing words were exactly what I needed. You already are someone. An avalanche of internet comments over the past few years had made me feel otherwise. The sneaking suspicion that I needed to accomplish something spectacular to be worth anything had left me exhausted. The treadmill of trying to be more had left me feeling less than enough. For so long I’d believed that I wasn’t up to the task of becoming a good grownup, much less the better grownup I wanted to be for myself and my kids. Yet I was already someone of value.

Hearing an adult I respected say these words was the moment I finally started to believe them.

I’d walked into the party that everyone called “adulthood” and didn’t know where to set my stuff. Awkwardly, I’d entered into this stage of life still carrying a backpack, bumbling around with a bag filled with so many things I’d thought I would easily outgrow. My insecurities were in there, as were my fears. There were stories being lugged around in that backpack—heavy stories, many of them untrue. Yet I’d been carrying that bulky thing everywhere, and it’d been weighing me down. A weight lifted.

There’s a Latin phrase, sum quod eris, which means “I am what you will be.” You can imagine a mentor saying this to an apprentice, or a parent saying it to a child. In some ways, this is said as aspirational: I am what you might one day become. This could also very easily be read as a threat. DO YOU SEE ME? This is what you’re becoming. This is where you’re headed. I AM WHAT YOU WILL BE! Initiate child’s nightmare mode.

This is not how elders lead. Yes, they are great examples and role models. However, better grownups aren’t on a mission to create duplicates of themselves. As I see it, a better grownup looks younger people in the eyes and tells them they’re already a vital note in the symphony. They’re waking people up to the irreplaceable miracle they are and to the irreplaceable miracle everyone around them is.

The image of adulthood in media (and in children’s artwork) is often unflattering. Parents on children’s shows are the butts of jokes. The grownups are portrayed as bumbling, dull, or emotionless. These images aren’t far off from those big, busy, and boring portraits of adults that kids had presented me with throughout the Listening Tour. The world might be crowded with poor models of adulthood—childish people stuck where they are, begging for power or attention. It’s a big responsibility, and you can do whatever you want. There are, though, many—like Michael, Catherine, and Cherese—who are quietly, daily answering the call to rise up and lead.

If you pay attention, you can hear it. Listen closely and you’ll begin to notice the urgent call for elders that’s being sung daily. It comes in whispers and shouts. It comes from kids and former kids, some carrying backpacks they should’ve checked at the door long ago. The call can be heard in the healing words of mentors, guides, and loved ones all around. Maybe, also, if we open our eyes, we’ll begin to see it, too. We’ll see true images of what it looks like to grow elder. We’ll start to recognize our elders, celebrate them, listen to them. And year by year, wrinkle by wrinkle, step by step, we’ll cheerfully become them.