Recently my wife texted me a picture of our kids. She was out with them at the grocery store, and the photo showed them standing and pointing with their eyes wide and their mouths open. You could sense the excitement. She then sent this text: “What do you think our kids are looking at?”

I responded with a question mark. She sent another photo. In it, the kids are standing in the exact same spot, but their eyes are even wider. Both our son and daughter appear to be squealing with delight.

She then asked me again: “What do you think our kids are looking at?”

This time I responded with multiple question marks and a confused-looking emoji. “What? What? I’m dying to know!”

She sent yet another photo. Even amid all the pointing and screaming, my wife had somehow been able to take multiple photos of our kids standing in the same spot. This was, in itself, a kind of parenting miracle. The kids continued to be frozen in wonder.

What were they looking at? What had captured their imaginations so fully? What had come into their lives and transfixed them to such a massive degree? A cardboard display for soda, of course. Really. It was just a large cardboard man and in his hand was a soda can. The can was mounted on little springs, making it move back and forth. That’s it.

I know you’re thinking, These people should take their kids out more. Yet if you’ve spent even just a little time around children recently, you’ll know that kids find joy in things we grownups might ignore. They play with boxes instead of the presents inside the boxes. They like the bubble wrap more than the expensive toy that the bubble wrap was protecting. They just see things differently than we do. Part of this has to do with their height, sure. How hideous we must look from their perspective! Have you ever accidentally reversed the camera of your cellphone and gotten a picture looking directly up your nose? Well, that’s about the vantage point many kids have of our faces. No wonder they have such mixed ideas about growing up.

Still, we’d do well to look at the world with childlike eyes. My children and all the kids I met along the Listening Tour possess uncanny abilities to see things in ways I’d forgotten. It’s a way of looking at the world with eyes full of radical amazement. For children, the quest for wonder isn’t so much a search but a zip code in which they already live. From there, they see everything. Clouds, crunching leaves, textures of blankets—all opportunities to sit in awe. Educator Walt Streightiff said, “There are no seven wonders in the eye of a child. There are seven million.”

This way of seeing the world was something I’d expected to find in kids. Yet as I began interviewing people who were much older, I discovered something surprising and enlightening. For some of these people it’d been many decades since they were children. Some of them were now in nursing homes or retirement facilities. Though they’d outgrown so much, these better grownups had held on to something from childhood and they weren’t letting go: eyes full of wonder.

At the age of 102, Mrs. Frances Hesselbein might very well be the youngest oldest person I’ve ever met. I share with you her age for the purpose of giving you and myself something wonderful to work backward toward. She told me that women love to ask her age. “Men never dare!” she said.

But when asked, her response is masterful: “I smile sweetly and say, ‘May I quote my grandfather?’ And they say, ‘Oh sure, please!’ And then I tell them, ‘My grandfather always said [now shouting], “Age is irrelevant! It is what you do with your life that counts!”’” This quieted them.

Mrs. Hesselbein always spoke with a mischievous gleam in her eyes. Even her saying “Hello, Brad!” made it sound like she was up to something. That’s because she’s always been up to something. She served as CEO of the Girl Scouts from 1976 to 1990. During that time, the number of young girls involved in the program went from being in decline to hitting more than two million active and passionate leaders in training. Plus, she was able to equip and empower more than seven hundred thousand adult volunteers to walk alongside these young women. She was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Bill Clinton in 1998. When introducing her, he made sure to mention her disapproval of “hierarchical words like up and down,” so he invited her to come not up, but instead to come forward to receive her recognition.

When the two of us spoke, she made no mention of receiving this honor, nor did she list qualifications off her résumé. Her love of words like forward did come up a lot, though. As someone in a leadership position, she realized early on that the language used in organizations was too often about moving up or falling down. There were superiors and inferiors. “I wanted everyone to be together in a circle,” she said. “Equal and growing together. Going forward together.”

“Circles, like around a campfire?” I asked.

“Yes! Around the warmth of a fire! What a circle! And oh, how we grow in circles.”

This woman was not the image of old that many might think of. Yes, her body movements were slow. Her speech and steps were carefully calculated. Yet these were not hindrances but just little details. Physical cues revealed that she’d had a few more birthdays than I had, but that’s it. Her vibrant enthusiasm, passion, and purpose eclipsed any physical signs of aging. It’s a spirit you might call youthful, or maybe elder. Undeniably, she was fully alive.

“Mrs. Hesselbein,” I whispered, as if we were kids in a tree fort, “what’s the secret?” I leaned in as I asked and eagerly awaited her response. Maybe she’d recommend a skin cream or prescribe me some specific diet. I wondered if there was a series of books I’d need to go through. Maybe a fountain somewhere I could visit and dip my face in every summer solstice. What was her secret to aging with such grit and grace?

She whispered back to me, playfully but earnestly: “To serve is to live.

“To serve is to live!” she repeated, louder this time. “You look to where you can serve. Where can you make a difference? It’s not a secret. I’ll say it loudly.”

This had been her battle cry. Looking back at all she’d accomplished, and at all she continued to accomplish, I realized that service really was a guiding principle throughout her life. “To be a good grownup means that we care about all people,” she told me. “It’s not just about yourself.” For more than a century now, she’d been on this planet and had used her time in service to others. Her eyes lit up as she detailed story after story.

It was the same wide-eyed spark I’d seen when I spoke with children. It was the same glimmer I’d continue to see in the eyes of all those grownups who’d held on to their childlike wonder. It was the wonder I’d seen in Walker’s eyes when he talked to me about the chapters of life. In our conversations, he’d warned me that life could contain regret or rejoicing. In my conversations with senior citizens I met, their eyes showed both.

Like Eugene. He’s ninety-two and in a retirement home. We’d initially connected over a game of checkers and continued our conversation into the afternoon. He was reserved but kind. Most of his answers were short, but one was especially so. When I asked him if he had any regrets, he responded:

“I should’ve called her back.”

That’s it. That’s literally all of the story he would share. He tried to repeat the sentence, but couldn’t complete it the second time. Too much pain. We’d only just met, and everything else in our conversation had been light and somewhat joyful. But that—that sentence came from a deep reservoir of regret. I didn’t push him for more details. His eyes told me enough.

He hugged me as we said our goodbyes, even though he didn’t seem like the type to do so. I thanked him for his time and his honesty and also assured him that he’d inspired me to love the people around me while I can. The corners of his mouth turned to a smile, and I could still spot a little light in his eyes.

The things we do have consequences. The same is also true for the things we don’t do. My new friend Mrs. Hesselbein had regrets, but she told me that they’re “few and far between.” She said the key is to “learn from the past, dream about the future, but keep focused on looking around you for who you can serve now.” It was a perspective that seemed childlike at first in its simplicity, yet was rooted in deep wisdom and experience. Almost as if she’d found a way to grow and move forward in life without losing that youthful spark.

I’ve always loved the story of Peter Pan. The idea of a boy who never grows up is fascinating. Since J. M. Barrie introduced the character and the idea, it has captured imaginations all over the world. He’s the embodiment of what it means to rebel against adulthood. To stick it to the grownups. This story has been told and retold, and often, in many ways, lived.

While the idea of never growing up might make a good story, the image of a grown man in green tights wandering through the woods or popping into bedroom windows is unsettling. There’s even a syndrome named after it. Psychologist Dan Kiley used the term Peter Pan syndrome in the 1970s to describe the behavior of an adult who does not mature socially. In real life there’s nothing adventurous about getting stalled in adolescence. The image of someone never growing into the person they’re meant to become—well, there’s a sadness to it.

But what if instead of celebrating Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up, we flipped the story and told it as Wendy, or The Girl Who Grew Up?

I think the story of Wendy is where the real adventure is. It’s about a child who, like all children, has great courage, compassion, and creativity. In this story, dear young Wendy is told by her father that it is time to leave the nursery. She will move from the comfort of the gentle place she has known her entire life and into a room of her own. Frightened and unable to sleep on the eve of knowing she must grow up, Wendy imagines a far-off world where she’ll never have to.

This Neverland is a world of her own making. There’s flying by starlight. Danger lurks at every corner. She soars with Peter Pan alongside her younger siblings. She’s brought them along, because even in the midst of such imaginative play, she can’t help remaining the caring sister. It is just who she is and who she’s becoming.

She delights in the idea of never growing up but throughout Neverland sees needs all around her: for a teacher, caregiver, storyteller, and guide. In this world, she finds rivalry and struggle, envy and violence. Innocence is threatened by the grownups who sail this world as pirates. The lost boys of Neverland are kids who’ve refused to grow up. Though she herself is scrappy and uninterested in leaving childhood behind, she looks at the rough-and-tumble Lost Boys and their leader, Peter Pan. She feels a deep sadness. Wendy determines to become neither pirate nor lost child. She decides that growing up would be the greatest adventure of all.

I think the best story would be a young girl who visited Neverland, bravely returned home, and never forgot it. We don’t need more Peter Pans. We need more Wendys. We need people who’ve flown, tasted magic, and dedicated themselves to carrying that wonder with them everywhere they go.

I get why Peter Pan stays in Neverland. But the real hero is Wendy. Though she wants to stay in the comfort of what she knows, she chooses growth. What if our culture celebrated the story of an inventive girl who is so brave and has so much moxie that she does the boldest thing of all: grows up? And what if this brilliant girl grows into a young woman who holds on to her imagination, even as the rest of the world tries to quiet it?

We can choose to remain stuck like Peter Pan. We can choose to remain suspended, stalled, scared children fearfully clinging to what we know. But wouldn’t it be more exciting to embrace an innocent openness to whatever might be next? Hanging on to the imagination you’ve had from the very beginning, yet growing in wisdom. Showing the world what can happen when a child grows into adulthood and yet somehow doesn’t forget the magic of growth. That’s the brave thing.

My 102-year-old friend Mrs. Frances Hesselbein regularly paused during our time together to grab my hand. She’d just smile and say, “Wow. We’re here!” Little interruptions to wake us both up to the wonder. Radical amazement at the simple fact that we were together. Maybe that’s something you start to realize once you’ve been alive for so many years. It’s a miracle we’re here. You start speaking like someone giving an acceptance speech at the Academy Awards, full of gratitude and realizing you don’t have much time.

Frances loves Ralph Waldo Emerson. “He said in 1847, ‘Be ye an opener of doors,’ and it is as relevant today as it was then,” she told me. “We open doors for ourselves, but we also open doors for other people. We’re all partners together on this marvelous journey.”

This marvelous journey, indeed. Better grownups open doors of possibility. They invite others into new ways of seeing. My ideas about aging were changing. For so long, I’d placed a wall between myself and older people. I’d believed I belonged forever at the kids’ table. Frances shattered that notion, or more aptly—she opened a door. She welcomed me to a circle. There I could see her humanity, and she could see mine. To me, respecting my elders meant leaving them alone. Peter Pan was whom I looked to. Now I want to be more like Wendy or maybe more like Frances, walking and flying with wisdom and wonder.

It was just an ordinary Tuesday when we spoke. Just another interview for my listening project. As we wrapped up, she told me, “Now you’re part of my story, and I’m part of your story! Isn’t that remarkable?” It is. It is remarkable. When we take time to see life with childlike wonder, we are reminded how life is relentlessly remarkable. I used to think life was relentless and occasionally remarkable, but now I know better. Each day we’re presented with an unending parade of wonders, should we not be too busy to notice. Even in the face of pain and difficulty, we can know we stand in the midst of something absolutely, completely, relentlessly remarkable. People, young and old, who live in radical amazement open us up to seeing more—souls in human bodies on a rotating rock in a universe held together by love. Or we could just call it Tuesday.

Our weird little lives are spent traveling on a ball around the sun, and somehow we act like this is normal. In all the everydayness of life, we forget the everythingness of life. Somehow the youngest and oldest among us already know this. We miss out on reasons to point and scream and laugh like my kids do. Noticing the immense beauty of each moment is something I don’t want to outgrow, though in many ways I already have. Thankfully, there are reminders all around us.

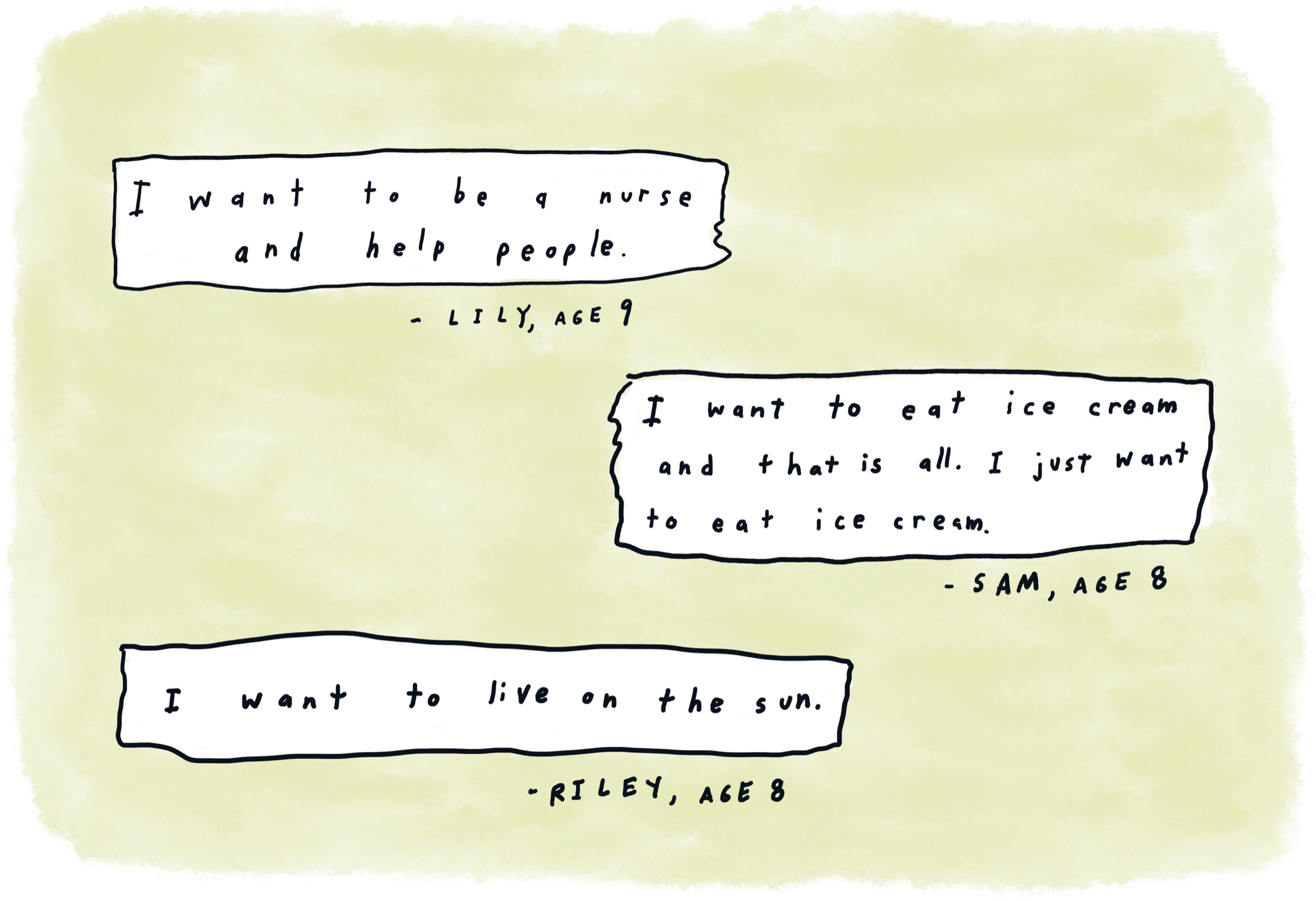

I’ve now heard so many children tell me what they want to do when they grow up. Hearing their responses, I know that only a fraction of them will actually follow through with it. I’ve seen what happens. We outgrow certain ideas and attitudes. Sometimes because they’re childish or preposterous. But too often, fears, uncertainties, or regrets cloud once wonder-filled eyes. Someone tells us we can’t do something and we believe them.

The more time I spent around children and the elderly, the more I began to recognize my own childishness. I’d dropped my backpack but hung on to so many things I should’ve outgrown, while at the same time I’d outgrown so many things I should’ve held on to. The trick is to trade in our childishness for things that are more childlike. To trade in our childish fear and in return receive childlike fascination. To exchange impatient tantrums for joyful tippy-toe dances no matter the circumstances. Selfishness for generosity. Busyness for bliss. It’s all about living with eyes full of wonder, like a child.

I used to carry a business card. I thought this was what you were supposed to do when you were a grownup. I’m not going to lie: I did feel pretty grownup when they came in the mail. Still, though, I felt like I was playing the part of a grownup. Handing them out never really led to a deeper connection. It was just a transfer of contact information. So I pitched them.

I made an entirely new card. It has very little information on it. Whenever I meet someone on a plane or at a business meeting, or anytime people are trading contact info, I carefully hand them the card. I let them know it’s their induction into the Wonder Society. I tell them to sign their name. Now they’re in my secret club.

Mrs. Hesselbein is in the Wonder Society, of course. So is every kid I met during my travels, as well as every elder. You can be a card-carrying member, too, though it doesn’t require a card. All it takes is opening your eyes. Be dedicated to wonder—see it, create it, and share it.

My son and I were going to the grocery store. He was in his car seat, and I looked in the rearview mirror to notice he had made circles with his thumb and index fingers placed over each eye like binoculars. I asked him what he was doing. He told me they were his “adventure goggles.” I guess one can never be too careful when going to the grocery store.

I decided to take his lead. With hand binoculars over our eyes, we marched through the store together like explorers. This grocery store was a place I’d been many times before, but now it was entirely new. Surely, it looked ridiculous, a grown man and a toddler playing pretend down each aisle. It was worth it, though, to hear my son’s laugh. It was worth it, too, for me to see such a normal outing through his bright, unclouded eyes.

While at the register, I could tell the cashier was curious, so I explained what we were doing. I held out my hands and pretended to give her a pair of adventure goggles. My son couldn’t believe it when he looked up and saw her hands over her eyes, too. “Wow,” she said.

I know. Wow.