It is claimed that only two persons know the complete formula for Coca-Cola syrup. Company policy forbids them from traveling in the same plane. When one dies, the other is to choose a successor and impart the secret to that person. So secret is Coca-Cola’s formula that the identity of the two initiates is itself a secret. Coca-Cola chairman Roberto Goizueta—a likely candidate because his background is in research and quality control—refused comment when Fortune magazine asked him in 1981 if he knew the formula. The written recipe is in a safe-deposit vault at the Trust Company of Georgia. The vault, it’s claimed, can be opened only with the approval of the Coca-Cola board of directors. Clearly, the syrup recipe is perceived as the heart and soul of the Coca-Cola organization. Said the 1981 Coca-Cola annual report, commenting on the Columbia Pictures acquisition, “Programming is to the communications and entertainment businesses what syrup is to the beverage business.”

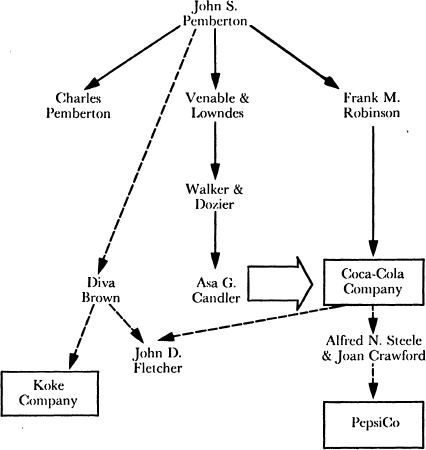

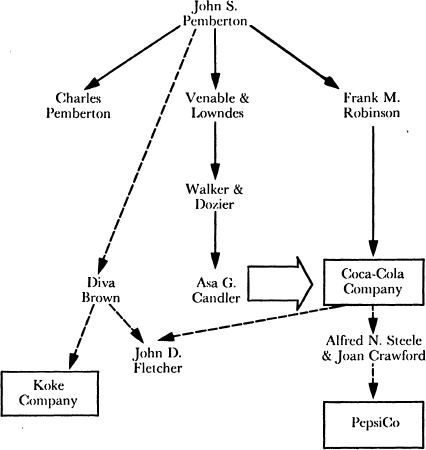

Security was not always so tight. Coke’s inventor, Atlanta pharmacist John Styth Pemberton, seems to have taken a casual attitude toward the recipe’s secrecy.

In 1885 Pemberton mixed up a pirated version of a popular drink of the time, Vin Mariani. Vin Mariani was a wine spiked with coca leaves. It was both an aperitif and a stimulant—something on the order of Dubonnet, only with cocaine in it. According to a promotional book, Ulysses S. Grant, Jules Verne, Emile

Zola, Henrik Ibsen, the Russian Czar, and Pope Leo XIII drank Vin Mariani. (Some historians think it was responsible for Thomas Edison’s insomnia.) Pemberton called his drink French Wine of Coca. Sales were disappointing.

The following year, Pemberton overhauled the formula. The wine was taken out. Still envisioning a stimulant product, he retained the coca leaf extract and added an extract of the African “hell seed” or kola nut. Kola nut contains caffeine, the same stimulant in coffee and tea.

Both coca and kola extracts are bitter. So Pemberton added sugar and flavorings to kill the unpleasant taste. The result was a syrup, not a beverage. The name “Coca-Cola” was adopted when Pemberton’s partner, Frank M. Robinson, decided that two Cs would work well in the Spencerian-script logo he was designing.

During its first years in Atlanta, Coca-Cola was sold at pharmacies as a syrup that could be taken as is or diluted with water. Nothing on the market today is a counterpart of the early Coca-Cola. Coca-Cola was promoted as a stimulant—more the 1880s equivalent of No-Doz or Vivarin than just a drink. But No-Doz and Vivarin are not seen as particularly healthful products; Coca-Cola was. Coke was stimulant, health tonic, and beverage.

Pemberton is known to have revealed the Coca-Cola formula to at least four persons. He told his partner/bookkeeper, Frank M. Robinson. Apparently Pemberton told his son, Charles. (Later, at the behest of the Coca-Cola Company founder Asa G. Candler, Charles signed a document renouncing his right to use the formula.) And Pemberton told Willis E. Venable and George S. Lowndes, the two men who purchased the formula in July 1887.

A scarce five months later, Venable and Lowndes themselves sold out. They transmitted the formula and rights to Coca-Cola to Woolfolk Walker and Mrs. M. C. Dozier. Then in two separate transactions in 1888, Walker and Dozier sold their rights and the formula to Asa G. Candler. The same year saw the death of John Pemberton and a new marketing angle: mixing the syrup with carbonated water.

Candler was the first to recognize the potential of Coke. He equally recognized the importance of keeping the formula a secret. Unfortunately, at least seven people knew the Coke formula by the time Candler got it. At least some of them no longer had any particular incentive to preserve the secret.

Candler tied up one loose end by taking on Pemberton’s old partner and one of the initiates, Frank Robinson, as his partner. Candler, evidently a more knowledgeable flavorist than Pemberton, soon revised the formula. By most accounts, Candler’s changes were improvements. They also entitled Candler to claim that the increasing circle of outsiders who knew Pemberton’s formula no longer knew the real Coca-Cola formula. In 1892, Candler, Robinson, and three others incorporated their operations as the Coca-Cola Company.

Candler instituted the shroud of secrecy that has since enveloped the formula. Candler and Robinson formed the first pair of initiates. Not until 1903 was anyone else allowed to make the syrup. The syrup was prepared in a locked laboratory, only Candler and Robinson having the combination to the door.

Shipments of ingredients were promptly deposited in the laboratory. There Candler or Robinson tore or scratched off the labels. They identified the ingredients by sight and smell. Lest a mail clerk learn the ingredients from the suppliers’ bills, Candler opened all the company’s mail himself. Likewise, Candler paid the bills himself to keep the accounting department from surmising any part of the secret. The invoices were kept in a locked file, and the only key to the file was kept on Candler’s key ring, recounts Candler’s son, Charles, in a 1950 biography, Asa Griggs Candler.

As the company got larger, Candler no longer could prepare all the syrup himself. In 1894 the first branch syrup plant was started in Dallas. Rather than relinquish the secret, Candler hit upon a scheme whereby people in other cities could prepare Coca-Cola syrup without knowing what was in it. The ingredients were numbered from 1 to 9, inclusive. Branch factory managers were told the relative proportions of the ingredients and the mixing procedure, but not the identities of the numbered ingredients. If the Dallas plant was running low on ingredient no. 6, it would order “merchandise no. 6” from Atlanta headquarters. Further to defy ready analysis, some of the merchandises were themselves mixtures of more basic ingredients.

To an extent, Candler was locking the barn after the horse had been stolen. It isn’t clear who among the early initiates talked, but it seems someone must have.

For instance, there was Diva Brown, a woman who claimed that John Pemberton had sold her the Coca-Cola formula shortly before he died. True or not, Brown had somehow gleaned enough information about Coke’s recipe to mix up passable imitations. She marketed Better Cola, Celery-Cola, Lime Cola, My-Coca, Vera-Coca, Vera Cola, and Yum-Yum in the southern states, claiming they were based on Pemberton’s formula.

The Koke Company claimed to have gotten hold of Brown’s formula upon her death in 1914 and thereby produced Koke, still another ersatz Coca-Cola. (For a long time, Coca-Cola neglected to trademark “Coke,” fearing the nickname would encourage substitution. So the Koke Company was able to call its product Koke until stopped by a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 1920.)

Meanwhile, John D. Fletcher, proprietor of a drink called “Coca and Cola,” also claimed to have learned the Coke formula from Brown. He further claimed to have seen the formula in a Coca-Cola lawyer’s briefcase during a protracted trial beginning in 1909, United States v. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca-Cola. Fletcher likewise was put out of business by a Coca-Cola lawsuit.

More problematic in the long run has been Pepsi-Cola, created by Caleb Bradham of New Bern, North Carolina, in 1898. The resemblance of the two drinks is all the more striking in view of the fact that kola nuts have little or nothing to do with the taste of either beverage (as we will see). Bradham did not have gas chromatography or other sophisticated analytic techniques. That he was able to produce such a convincing imitation of Coca-Cola suggests that he had heard something too.

In 1949 a top Coca-Cola Company executive, Alfred N. Steele, defected to PepsiCo. Steele’s actress/wife, Joan Crawford, defected as well; Crawford had done endorsements for Coca-Cola. Steele was followed by several colleagues from Coca-Cola. After joining Pepsi, Steele boasted, “Their [Coca-Cola’s] chemists know what’s in our product, and our chemists know what’s in theirs. Hell, I know both formulas.”

Steele had been in Coca-Cola’s marketing division, not in quality control. Whether Steele was one of the few formally initiated into knowledge of the full formula is questionable. But there can be little doubt about the contention that Pepsi knows Coke’s formula (or most of it) and vice versa. There are ways of analyzing soft-drink flavorings, and it is hard to believe that both Coke and Pepsi haven’t been thoroughly scrutinized by their competitors.

If Pepsi really knows Coke’s secret, why hasn’t it become a clone of the more popular drink? Most likely, Pepsi has considered the economics of duplicating Coke and decided against it. Being a larger company, Coca-Cola can produce its beverage at a lower unit cost than Pepsi could. In head-on competition with indistinguishable products, Pepsi would have to charge a higher price and eventually lose out. Instead, Pepsi produces a drink different enough from Coke that a segment of the public prefers it to Coke.

Today the Coca-Cola Company is nearly mute about Coke’s flavoring ingredients. It no longer even mentions kola nuts in promotional literature. A short brochure, You asked about soft drinks… is bold enough to deny cocoa as an ingredient. (Some people confuse cocoa with coca.) If you write to ask if there is something truly repugnant in Coca-Cola, the company will, of course, deny it. Coca-Cola denies, for instance, pig blood, a rumored ingredient that has hurt sales to African Moslems. In E. J. Kahn, Jr.’s study of Coca-Cola, The Big Drink, he mentions the equally dubious rumor of peanuts as an ingredient—from former Coke president Robert W. Woodruff’s peanut plantation.

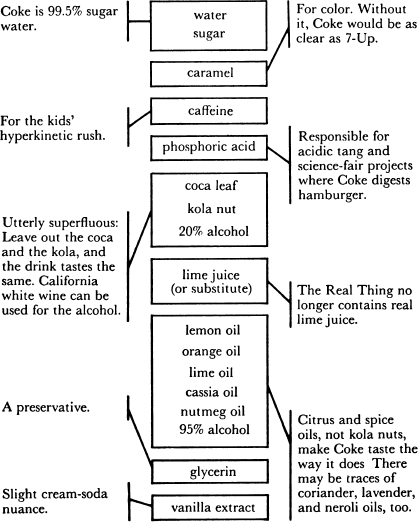

Coke’s label discloses, “Carbonated water, sugar, caramel color, phosphoric acid, natural flavorings, caffeine.” Everything that makes Coke unique is subsumed under “natural flavorings.”

The known ingredients can all be squared with Candler’s system of numbered “merchandises.” It is known that sugar is merchandise no. 1, caramel is no. 2, caffeine is no. 3, and phosphoric acid is no. 4. The water and carbonation apparently don’t rate a merchandise number.

Coke’s sugar used to be pure sucrose. Since 1980, syrup producers have been permitted to substitute high-fructose corn syrup for as much as 50 percent of the sugar. Some purists think the Coke with corn syrup doesn’t taste as good. Before the change, former Coke Chairman J. Paul Austin knocked corn syrup: “It produces a chemical reaction with the Coca-Cola that throws the flavor off,” he said in Fortune. Pepsi still uses sugar only. Not everyone notices the difference between sugar and corn syrup, but those who do apparently favor sugar. By one hypothesis, this slight tipping of the flavor scales in favor of Pepsi recently made it possible, for the first time, for Pepsi to gather “evidence” that most people favor Pepsi over Coke and use it in ads.

Coke’s caramel is intended only as coloring. Virtually all Coke’s brown color comes from the caramel. Coke’s caramel is burnt cane or corn sugar.

Caffeine is the stimulant principle. Though it was Pemberton’s idea to use natural extracts of kola nuts (containing caffeine) and coca leaves (containing cocaine) for stimulant effect, the amount of these ingredients in Coke is far too small to be significant. Nearly all the caffeine in Coke is chemically pure caffeine, a white powder.

Caffeine has a strong, bitter taste. The bitterness is largely covered up by the massive amounts of sugar used and the other fiavorings. At the time of the United States v. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca-Cola trial, the caffeine used in Coke was refined from tea dust. During World War II, caffeine was scarce, and Coke’s chemists toyed with the idea of synthesizing caffeine from bat guano. Coca-Cola executives rejected the plan on the grounds that the possible discovery of bat droppings as an “ingredient” of Coke would be too damaging. Coke may now be getting its caffeine from the guarana shrub of the Amazon basin; the seeds of these shrubs contain 5 percent caffeine.

The phosphoric acid provides a flat acidity. Other acids commonly used in soft drinks, such as citric or tartaric, suggest the acidity of specific fruits. Phosphoric acid doesn’t. Pepsi lists both phosphoric and citric acids on its label, reflecting a more lemony acidity.

So much for merchandises 1 through 4. Several clues to the other ingredients come from the writings of Charles Howard Candler, son of the Coca-Cola Company’s founder and an initiate. In his biography of his father, Candler tells of the merchandises: “The ingredients of Coca-Cola, throughout its early history, were categorized and referred to by numbers from one to nine inclusive …”

At another point, Candler tells where they bought the ingredients: “Among the suppliers of essential ingredients in the period under discussion were the E. Berghausen Chemical Company of Cincinnati; the Maywood Chemical Works, of Maywood, N. J.; the Monsanto Chemical Company of St. Louis; the Mallinckrodt Chemical Works, also of St. Louis; Harshaw, Fuller and Goodwin Company of Elyria, Ohio; and Procter & Gamble of Cincinnati.”

In 1953, the younger Candler published another cola memoir, Coca-Cola & Emory College. In it he provides some cagey hints about the changes his father made in the Coca-Cola formula:

Some of the very same people to whom he [Asa G. Candler] had paid hard-earned cash for what was then generally considered of little value, constantly plagued him by making and selling to unscrupulous dealers imitations of and for Coca-Cola, asserting that their concoctions were made from or based upon the original Coca-Cola formula. These unfair competitors may have had some knowledge of the Pemberton formula, but they knew absolutely nothing of the composition of the formula with which Asa G. Candler made Coca-Cola. The Pemberton product did not have an altogether agreeable taste, it was unstable, it contained too many things, too much of some ingredients and too little of others.

Father’s pharmaceutical knowledge convinced him that the formula had to be changed in certain particulars to improve the taste of the product, to insure its uniformity and its stability. Some of the ingredients were incompatible with others in the formula; the bouquet of several of the volatile essential oils previously used was adversely affected by some ingredients. Several needed materials, one notable for its preservative virtue, were added. The first thing he did was to discontinue the use of tin can containers for shipping. On account of the inclusion of a very desirable constituent in the formula, the use of tin cans was dangerous.

Here the “people to whom he had paid hard-earned cash” would include Walker, Dozier, and also the Pembertons, who retained an interest in Coca-Cola for several years. The second ingredient Candler hints at, the one that doesn’t go with tin cans, is easy to guess. It’s phosphoric acid. Phosphoric acid eats through tin, forming poisonous tin phosphate. (Currently, Coke uses stainless-steel containers.)

That means that the phosphoric acid was Candler’s innovation and wasn’t in the original formula. But Charles Candler says in the same book that the Pemberton formula included “an acid for zest.” Perhaps this acid was one of the ingredients Candler took out of the formula. Or it could have been lime juice.

Lime juice is one of the ingredients that has been reported in chemical analyses of Coke. Several analyses of Coke were offered as evidence in the United States v. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca-Cola trial. In 1909 the federal government seized the latter quantity of Coca-Cola syrup en route from Atlanta to a bottling plant in Chattanooga and charged Coca-Cola with violation of the Pure Food Act. Trial and appeals ran about a decade. One analysis of the syrup claimed:

Caffein (grains per fluid ounce) 0.92-1.30

Phosphoric acid (H3P04) (percent) 0.26-0.30

Sugar, total (percent) 48.86-58.00

Alcohol (percent by volume) 0.90-1.27 Caramel, glycerin, lime juice, essential oils, and plant extractives Present

Water (percent) 34.00-41.00

Another analysis from the trial ran:

Caffeine 0.20 per cent or 1.19 grains per ounce.

Phos. Acid 0.19 per cent.

Sugar 48.86 per cent.

Alcohol 1.27 per cent.

Caramel, glycerine,

Lime Juice, oil of cassia

Water about 41 per cent.

There seems little doubt that Coca-Cola contained lime juice circa 1909. To confirm its presence in Coke today, Big Secrets wrote the Coca-Cola Company asking about lime juice. Bonita Holder of Coca-Cola replied: “While we are unable to comment specifically on the various flavors utilized in Coca-Cola, I can nonetheless confirm for you that Coca-Cola contains no lime juice, or any fruit juice.”

Lime juice is perishable and somewhat cloudy; it varies with each season’s crop. Coke therefore might have wanted to replace it with a more stable substitute. A mixture of citric acid and some of the flavoring principles of lime juice (which are distinct from those found in the oil of lime peel) might have been substituted for the original lime juice without anyone noticing much of a change in the taste of Coca-Cola. Citrus juices are easy to fake. Coca-Cola produces such soft drinks as Hi-C Orange, Hi-C Lemonade, Hi-C Punch, and Hi-C Grape, which don’t contain any fruit juice either.

The analyses mention three other ingredients: alcohol, glycerin, and oil of cassia. Evidently glycerin is the preservative Candler described. It is a customary ingredient in soft-drink syrups. It is believed to prevent separation of essential oils on standing.

Coke syrup is about 2 proof. The alcohol probably only enters in as a solvent for the “plant extractives.” Oil of cassia seems to be one of the essential oils that provide Coke’s flavoring. Cassia is a form of cinnamon, sometimes called Chinese cinnamon to distinguish it from true or Ceylon cinnamon. Most of the stick cinnamon sold in supermarkets is Ceylon cinnamon. Most of the cinnamon used in commercial baked goods such as coffee cakes is cassia.

Conspicuously absent from the above analyses is any mention of coca or kola. This was one of the main issues of the United Statesv. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca-Cola trial. Coca leaves contain cocaine; ergo, it was claimed that Coca-Cola must either contain that recently outlawed drug, or the coca must have been dropped from the formula. In the latter case, the government charged, it was mislabeling to use “Coca” in the name. Further, it was charged the kola in Coca-Cola was an imposition—a trace ingredient added only so that the company could claim it was there. Thus the “Cola” part of the name was misleading, too.

Indeed, there is precious little coca or kola in Coca-Cola. None of the chemical analysts consulted at the trial were able to detect coca or kola. But there are traces of coca and kola present, in what Coca-Cola calls merchandise no. 5. At the time of the trial, merchandise no. 5 was manufactured by a contractor, the Schaeffer Alkaloid Works of Maywood, New Jersey. Its president, Dr. L. Schaeffer, described the manufacture of Coke’s fifth ingredient:

Q. Now, Doctor, do you make Merchandise No. 5 for the Coca-Cola Co.? A. Yes, sir.

Q. From what substance do you make that Merchandise No. 5?

A. Of the Coca leaf and the Cola nut, and of dilute alcohol sir.

Q. What do you use the alcohol for, what is the purpose of putting in the alcohol?

A. To extract from the bodies mentioned the extractive matter.

Q. Do you use anything else in that compound except the extracts from the coca leaves and cola nuts and dilute alcohol?

A. No, I do not use anything to speak of, or essentially. Q. Now just state the process, Dr. Schaeffer, by which you manufacture this Merchandise No. 5?

A. The process consists of two parts. The first part is to decocanize the coca leaf, the second part is to use the decocanized coca leaf and cola nut, both of which are in powdered form, to make the infusion, that is, the same extract made by percolation with dilute alcohol. … The proportions which are used in the process are as follows: 380 lbs. of coca leaf, 125 lbs. of cola nuts and 900 gallons of dilute alcohol of about twenty per cent strength …

The cocaine was removed from the coca leaves by rinsing with toluol, a solvent. Cocaine dissolves in toluol; repeated rinsing leaches away the cocaine.

According to Dr. Schaeffer’s testimony, there was wine In Coca-Cola. The alcohol used in making merchandise no. 5 was usually a mixture of California white wine and 95 percent commercial alcohol. But Dr. Schaeffer sometimes used an alcoholwater mixture “if California wine is too high in price. It is altogether a matter of price of the wine or of the alcohol.”

Merchandise no. 5, according to testimony, was a dark, winey liquid. Several of the witnesses were given samples of merchandise no. 5. One thought it tasted and smelled no different from the wine it was made from. One Coca-Cola witness claimed it had the characteristic odor of coca but proved unable to describe the odor. Another witness said it smelled like toluol, the toxic solvent that isn’t supposed to be present in the final product at all.

An experiment was performed for the benefit of the court. Coca-Cola made up a special batch of syrup containing no merchandise no. 5. Witnesses thought it tasted the same as the regular syrup.

In short, neither coca nor kola has much, if anything, to do with the taste of Coca-Cola. Both substances, in fact, have unpleasant, bitter flavors wholly unlike that of Coca-Cola.

Pemberton, remember, was concocting a medicinal syrup. Because his two active ingredients had unpleasant flavors, he masked them with other flavors—the way a codeine cough syrup might be cherry-flavored.

As it happened, Coca-Cola became successful for its flavor rather than for any medicinal value. Dozens of imitations sprang up, most with “Cola” in their name. Thus “cola” became the generic term for soft drinks similar to Coca-Cola. Most—though not all—of these imitations contained kola nuts. But as with Coke, the kola really didn’t contribute to the flavor.

Cherry cough syrup tastes like cherries. The “cola” flavor tastes like … nothing familiar. That raises two possibilities. Cola flavor may come from an exotic substance, otherwise unknown to Western taste buds. Or it may be what the soft-drink industry calls a “fantasia” flavor, a new flavor created by the artful combination of other flavors.

The basics of cola flavor are no mystery. Pepsi, Royal Crown,

and every supermarket chain know enough about the Coca-Cola formula to make good imitations. The cola flavor is a fantasia blend of three familiar flavors: citrus, cinnamon, and vanilla.

The prevailing philosophy, and certainly the philosophy behind Coca-Cola, is that these flavors should be blended so that none predominates and becomes identifiable in its own right. To the average palate, Coke does not taste like citrus, cinnamon, or vanilla.

But some of the cheaper, supermarket house-brand colas taste slightly of cinnamon or vanilla. Pepsi has a more lemony taste than Coke—and Pepsi Light advertises its lemon flavor.

Here citrus means the oils pressed from the peels. The oils are responsible for most of the smell of citrus fruits but taste nothing like the juice. All citrus oils are very bitter by themselves. Diluted in a soft-drink emulsion, they acquire a more pleasant taste.

All three familiar citrus fruits—oranges, lemons, and limes—are probably used in Coca-Cola. At any rate, Pepsi-Cola, which is more candid about its formula, admits to orange, lemon, and lime oils (as well as vanilla and kola nuts) in a brochure, Pepsi-Cola: Quality in Every Drop. The theory always has been that Coke has relatively more orange and less lemon than Pepsi. Food writer Roy Andries de Groot tells of plying a Coca-Cola Company executive with rum-and-Cokes to get an admission. According to de Groot, the executive uh-huhed the Coke:orange/Pepsi:lemon analysis.

How are these ingredients combined? The sources Big Secrets consulted pointed to a book, Food Flavorings: Composition, Manufacture, and Use, by Joseph Merory (second edition, 1968). Merory was the founder and president of Merory Food Flavors, a small flavoring supplier in Fairfield, New Jersey. To the horror of many of his colleagues, Merory published dozens of standard flavoring formulations in the book, drawing on his own experience and what was common knowledge in the flavoring industry. One of his recipes, designated MF 241, is a “cola flavor” that seems to be Merory’s version of Coca-Cola. Another recipe, “Cola Syrup” MF 234, suggests Pepsi.

The seeming Coca-Cola recipe, MF 241, is for a cola flavor, which must be mixed with sugar syrup and phosphoric acid to produce cola syrup. Cola syrup in turn must be mixed with car bonated water to produce the finished drink. Merory’s recipe specifies these ingredients:

Caramel (32 fluid ounces)

Lime juice (32 fluid ounces)

Glycerin (16 fluid ounces)

Alcohol (95 percent) (12 fluid ounces)

Cola flavor base (12 fluid ounces)

Kola nut extract (12 fluid ounces)

Caffeine solution (2 ounces of caffeine in 10 fluid ounces of water)

Vanilla extract (2 fluid ounces)

These are mixed to produce 128 ounces (1 gallon) of cola flavor. Four ounces of this cola flavor, plus.5 fluid ounce of diluted phosphoric acid (one part 85 percent phosphoric acid to seven parts water), are used to flavor a gallon of sugar syrup. The composition of the cola flavor base and the kola nut extract are given in accompanying recipes.

This recipe suggests the identities of the unknown merchandises. Merchandise no. 1, sugar, is the syrup to which the cola flavor is added. Nos. 2 and 3, caramel and caffeine, are in the recipe, caffeine in a water solution. No. 4, phosphoric acid, is added to the sugar syrup. No. 5, in Coca-Cola’s recipe, is coca and kola extract in an alcohol-water solution. This corresponds to two ingredients in the Merory recipe: the kola nut extract and the 95 percent alcohol. The kola nut extract is to be prepared according to another Merory recipe, MF 237. This requires that kola nuts be extracted with a solvent, propylene glycol, most of which is then distilled off. Water is added, so the result is a water-based extract of kola. Were alcohol added to this extract, you’d have a sort of merchandise no. 5 (without the coca, though). Of course, the alcohol and kola extract can be treated as separate ingredients—which is how Merory lists them.

There are four remaining ingredients in Merory’s list—and four remaining merchandises of the nine Candler claimed. Merory’s four are lime juice, glycerin, a cola flavor base, and vanilla extract. Of these, the first two were reported in lab analyses of Coke (though Coke now denies lime juice). The last, vanilla extract, is a generally acknowledged component of the cola flavor.

It is tempting if not compelling to identify these four with merchandises nos. 6 through 9. We can’t be sure that Coca-Cola doesn’t mix together glycerin and vanilla extract, say, and call it merchandise no. 6. But since glycerin and vanilla extract must be prepared or purchased separately, it makes sense to consider them as separate merchandises. The cola flavor base is a composite product—a mixture of citrus and spice oils in alcohol. It includes all the essential oils used in the cola. Because essential oils are powerful flavorings and must be diluted, it makes sense to mix them up in a large batch (to ensure a uniform product) and to draw from this premixed batch as needed. The oil mixture would then be regarded as a single ingredient.

The oil mixture may be the mysterious ingredient 7X of Coke lore. Merchandise 7X is the most secret of Coke’s secret ingredients. The “X” has never been explained; 7X seems to be simply merchandise no. 7. It might make sense if there was a merchandise no. 7 composed of many ingredients, all given letters: 7A, 7B, 7C … 7X. But no one associated with Coke has ever alluded to any of the other members of this hypothetical series. What’s more, we know that 7X is itself a composite ingredient. Charles Candler writes of making “a batch of merchandise 7X” while his father supervised the measuring and mixing.

Certainly the essential oil mixture is the most important component of a cola’s flavor. The “cola flavor base” referred to above is given in another Merory recipe, MF 238. It is made from the following:

Cold-pressed California lemon oil (46.80 grams)

Orange oil (24.84 grams)

Distilled lime oil (14.20 grams)

Cassia or cinnamon oil (10.65 grams)

Nutmeg oil (3.50 grams)

Neroli oil [“can be omitted,” says Merory] (0.01 gram)

If the aforementioned analysis presented at the United States v. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca-Cola trial was correct, it is cassia rather than true cinnamon oil that is used in Coca-Cola. Nutmeg is a likely minor component of the Coca-Cola flavor base, for aside from Merory’s equivocal endorsement of it here, it has been claimed detected in outside chemical analyses. Neroli is an oil distilled from the blossoms of the bitter orange tree. It forms only one part in ten thousand of Merory’s oil mixture, though. That and the difficulty of distinguishing citrus oil in chemical analysis make it hard to say if neroli oil is in Coca-Cola. According to the Merory recipe for flavor base, the above mixture of oils (100 grams) is mixed with 11 fluid ounces of 95 percent alcohol and shaken. Five ounces of water are added, and the mixture is left to stand for twenty-four hours. A cloudy layer of terpenes will develop; only the clear part of the mixture is taken off and used in recipe MF 241.

There may be other ingredients in the Coca-Cola oil mixture. In The Big Drink, E. J. Kahn, Jr., mentions the possibility of lavender as an ingredient. The alternate Merory cola recipe, which uses citric acid and less orange oil, suggesting a Pepsi-like product, includes coriander in lieu of nutmeg. (Coriander is a spice found in Danish pastries.) Perhaps there is a trace of coriander in Coca-Cola. In another of the occasional breaches of industry closemouthedness, flavorist A. W. Noling published a pamphlet on colas in 1952. The Hurty Peck Pamphlet on Cola attributed the secret of cola flavor to extracts of decocanized coca leaves and kola nuts, oils of lime, lemon, orange, cassia, nutmeg, neroli, cinnamon, and coriander, and lime juice and vanilla. Noling’s analysis seems to have been directed specifically at Coca-Cola. Among modern cola drinks, only Coca-Cola is known to use the coca leaves.

The proportions in the accompanying recipe are based on the analyses of Coke quoted above and Merory’s recipes. The amount of caffeine agrees with that stated in Coca-Cola’s So you asked about soft drinks … pamphlet; this is about a third of the caffeine found in the trial analyses.

The following recipe produces a gallon of syrup very similar to Coca-Cola’s. Mix 2,400 grams of sugar with just enough water to dissolve (high-fructose corn syrup may be substituted for half the sugar). Add 37 grams of caramel, 3.1 grams of caffeine, and 11 grams of phosphoric acid. Extract the cocaine from 1.1 grams of coca leaf (Truxillo growth of coca preferred) with toluol; discard the cocaine extract. Soak the coca leaves and kola nuts (both finely powdered; 0.37 gram of kola nuts) in 22 grams of 20 percent alcohol. California white wine fortified to 20 percent strength was used as the soaking solution circa 1909, but Coca-Cola may have switched to a simple water/alcohol mixture. After soaking, discard the coca and the kola and add the liquid to the syrup. Add 30 grams of lime juice (a former ingredient, evidently, that Coca-Cola now denies) or a substitute such as a water solution of citric acid and sodium citrate at lime-juice strength. Mix together 0.88 gram of lemon oil, 0.47 gram of orange oil, 0.27 gram of lime oil, 0.20 gram of cassia (Chinese cinnamon) oil, 0.07 gram of nutmeg oil, and if desired, traces of coriander, lavender, and neroli oils, and add to 4.9 grams of 95 percent alcohol. Shake. Add 2.7 grams of water to the alcohol/oil mixture and let stand for twenty-four hours at about 60 ° F. A cloudy layer will separate. Take off the clear part of the liquid only and add to the syrup. Add 19 grams of glycerin (from vegetable sources, not hog fat, so the drink can be sold to Orthodox Jews and Moslems) and 1.5 grams of vanilla extract. Add water (treated with chlorine) to make 1 gallon of syrup.

Yield (used to flavor carbonated water): 128 6.5-ounce bottles.

The amount of kola in this recipe—or in any cola—is tiny. Some colas are reported to contain none at all. By this recipe, a gallon of cola syrup is made from 0.37 gram of kola nut. But a gallon is 128 fluid ounces, and each ounce can flavor a bottle of finished, carbonated beverage. So the amount of kola nut used in making a bottle of cola drink is about 3 milligrams. That tiny speck is merely soaked in alcohol and then discarded, only the alcohol going into the cola syrup.

Many Coca-Cola drinkers swear that the drink tastes different in various parts of the country. Coke’s standard answer is to blame the mineral content of the water used by the bottling plants. (Now that the syrup plants have the option of using corn syrup for part of the sugar, the Coke in regions where they do use corn syrup ought to taste different from—probably not as good as—the Coke where only cane sugar is used.) Where soda fountains still make Coke from syrup, another variable is the “throw”—the amount of carbonated water added to the syrup. Southerners tend to like Coke on the syrupy side.

Coca-Cola was not always alone in its use of coca. There were coca elixirs and beverages before there were colas. Until 1903, Coca-Cola contained the full cocaine content of its coca extract. Since then, Coca-Cola has taken great pains to remove the cocaine from the coca leaves before they go into merchandise no. 5. According to one source, there were sixty-nine imitations of Coca-Cola still containing measurable cocaine in 1909.

One version of the chestnut about putting an aspirin in Coca-Cola says that the cocaine is thus precipitated. (The more usual version holds that the aspirin-Coke mixture acts as a Mickey, the opposite of what would be expected from cocaine.) Of course, the Coca-Cola Company bristles at any suggestion that there might still be cocaine in the drink.

Even before 1903, the amount of cocaine in Coca-Cola was trifling. One analysis put the cocaine content of an ounce of Coca-Cola syrup—in the pre-extraction days—at 0.04 grain (2.6 milligrams).

That’s not much. In small doses, cocaine has roughly the stimulant effect of a dose of caffeine ten times larger. A milligram ofcocaine might have the effect of 10 milligrams of caffeine, and so forth. So the cocaine in an ounce of the old syrup had the stimulant effect of about 26 milligrams of caffeine. In comparison, a cup of tea contains about 60 milligrams of caffeine.

By the same analysis, the old Coke syrup contained about 1.21 grains (78 milligrams) of caffeine. Even when Coke contained measurable amounts of cocaine, most of its stimulant effect must have been from the caffeine.

Figure that a line of uncut cocaine is about 50 milligrams. Then it would have taken nearly 20 ounces of the old Coca-Cola syrup (or 20 of the 6.5-ounce bottles of carbonated beverage) to represent an equivalent amount of cocaine. Anyone trying to consume that much would have gotten sick from the caffeine, phosphoric acid, or sugar.

From time to time, various chemists and government agencies have wondered if there is any residual cocaine in Coca-Cola even yet. In 1912, nine years after the switch to decocanized coca leaves, a Canadian government study found no cocaine in Coca-Cola syrup.

In 1972 Dr. Norman Farnsworth of the University of Illinois, Chicago, had graduate students test Coke and other colas for cocaine. A gas-chromatography “peak” near that expected for cocaine was found. To confirm the apparent finding, Farnsworth’s group added cocaine to a sample of Coca-Cola and retested. This time there were two peaks—meaning that something other than cocaine was causing the first peak. A scientific paper reporting the original finding was hastily shelved.

So jittery was the Coca-Cola Company on hearing of the results that it funded further research to find the cause of the spurious peak—lest a less careful researcher might report the “cocaine.” Farnsworth finally concluded the peak was due to a polymer formed from the ammonia used in the gas chromatography.

You can make a strong argument that there must be some cocaine in Coca-Cola nonetheless. The decocanization process used on the coca leaves that go into Coke is similar to the decaffeination of coffee. A solvent is passed through the leaves repeatedly, leaching away a little more cocaine each time. So it is with the caffeine in decaffeinated coffee. But no coffee producer claims its decaffeinated coffee is entirely free from caffeine. A brand that advertises itself as 98 percent caffeine-free contains only 2 percent of the caffeine of regular coffee. For all practical purposes, that’s good enough.

Coke’s decocanization is good enough, too, as far as the drug laws are concerned. No one suggests that there is enough cocaine in a bottle of Coke to have any physiological effect whatsoever. But it’s quite another thing to assert that there is no cocaine in Coca-Cola. A molecule of cocaine, the smallest possible amount, weighs 0.000000000000000000504 milligram. If an ounce of the old syrup contained 2.6 milligrams of cocaine, then it must have contained about 5 quintillion (5,000,000,000,000,000,000) molecules of cocaine.

Does Coke’s decocanization process catch every last one of those 5 quintillion molecules? Surely not. If it removed 99 percent of them—which would be pretty good—there would still be a whopping 50 quadrillion molecules left.

Even if the Coca-Cola Company invested in a hypothetical superdecocanizer capable of removing 99.99999999 percent of the cocaine (a pointless waste of money, given the insignificant role of coca extract in the finished beverage), there would still be millions and millions of molecules of cocaine left in every bottle of Coke. As long as Coca-Cola is made from coca leaves, it can hardly avoid containing cocaine.