Nearly all commercial perfume formulations are secret. A typical heavily merchandised fragrance—Chanel No. 5, Bal à Versailles, Joy—is a blend of many scents. Industry conviction is that a perfume that simulates a single, identifiable scent, such as rose or orange blossom, is difficult to market: Consumers assume a complex scent is better. Prospective customers are less likely to reject a scent if they can’t explain why they don’t like it. Instead of saying, “No, that smells like lily of the valley, and I don’t like lily of the valley,” they say, “Maybe.” Or so the industry postulates.

Blending perfumes is a complex business. Good perfumers command salaries commensurate with those of investment bankers. It often takes years to formulate a fragrance. Some perfumes are reputed to contain as many as three hundred ingredients. Insiders say the large perfume houses routinely analyze each new competing fragrance as it is introduced. The analytic powers of “noses”—skilled perfume blenders—are legendary but have limits. Increasingly, gas chromatography and kindred techniques are used for analysis. Any sufficiently popular new fragrance is soon copied by competing manufacturers and sold under a different name. Thus Estée Lauder’s Cinnabar, a cinnamonlike Oriental-type fragrance, seems to have inspired Yves Saint Laurent’s Opium.

Most controversial of the hundreds of ingredients used in perfumes are the animal products. All are expensive, all are unsavoryin the raw state, and all impari delightful notes when blended properly. Four animal products are used. None is urine (not that what they are is any more appealing).

Ambergris is a wax-or pitchlike substance found floating in topic seas. It was used for fragrance, flavor, and alleged aphrodisiac properties long before anyone knew what it is. At various times, ambergris was held to be a gum; a bitumen; sea foam mysteriously solidified; the caked excrement of seabirds; a marine fungus; or honeycombs fallen into the sea from cliffside hives. Ambergris is now known to come from the sperm whale. The whale eats squid, and squid have sharp, indigestible “beaks.” Ambergris is a secretion produced when the beaks irritate the wall of the whale’s intestine. Squid beaks are often found in lumps of ambergris. It is not certain if the ambergris normally passes through the digestive tract or remains in the whale until death (lumps as large as 336 pounds have been reported.) Whaling ships occasionally take ambergris from fresh kills. Then the ambergris is black, tarry, and evil-smelling. Aged ambergris found in the ocean or on beaches may be hard, translucent, and white, gray, yellow, reddish, or striped. At best the odor is sweet, earthy, and lingering—a quality perfumers call “velvetiness.”

Civet is a thick, yellowish secretion of anal glands of the civet cat of Asia and Africa. It figures in several confused stories about Chanel No. 5. Civet (or bobcat urine in some variations) is said to be an ingredient of Chanel No. 5. Some cat owners boycott Chanel perfume on the grounds that the animals are tortured. The civet cat is not really in the cat family, but it is a mammal capable of feeling discomfort. The secretion is produced by glands comparable to those that produce the scent in a skunk, and it is collected regularly from living animals. The animals are alleged to produce more civet when closely penned or agitated. As the animals are raised by independent operators unaffiliated with the major perfume houses, the claims of mistreatment are plausible. Civet’s odor is objectionably musky at full strength; but pleasant when diluted.

Musk is usually a hardened, granular secretion from the male musk deer of Asia. Musk comes in a pouch, which is cut off and sold. Musk costs about twelve thousand dollars a pound. Frequently the musk is emptied from the pouch, cut with cheaper substances, and replaced. Musk’s fragrance is not as lingering asthat of ambergris. But musk’s odor is so penetrating that it cannot be washed off polished steel. Despite its high price, musk is such a concentrated scent that it is probably never much of a factor in the price of a bottle of perfume. Castoreum, the fourth animal product used in perfumery, is a similar secretion, from the beaver.

How widespread is the use of animal products? One industry observer consulted thought it was decreasing—not so much because of cost as because of animal-protection lobbies. Only freefloating ambergris, of all the animal products, does not involve some form of molestation. Three prominent perfume houses were queried about use of animal products. Estée Lauder responded that it uses castoreum, civet, and musk in its perfume. According to Lauder’s spokesperson, ambergris is not used by U.S. firms because of the whale’s endangered-species status. Chanel acknowledged the use of civet in Chanel No. 5, noting that “most, if not all, other manufacturers of fine fragrances” do the same. Jean Patou denied use of any animal products in its Joy perfume.

Of course, animal products are only a small part of the picture. Despite trade secrecy, most perfumers have rough ideas of the composition of the major competing perfumes. Fragrance trade journals and books detail representative formulas, including occasional outside analyses of name perfumes. Big Secrets canvassed perfumers and fragrance ingredient suppliers for their ideas about several well-known perfumes. What follows are educated guesses. If, as seems likely, some of the actual formulas include dozens of trace ingredients, none of the sources consulted could identify them with any confidence. Nor is it always possible to distinguish a good synthetic component from its natural counterpart. Fragrances are listed in order of increasing retail price as of late 1982.

Bergamot, an obscure citrus fruit, seems to dominate Eau Sauvage. Because most men’s colognes imitate the original eau de cologne devised by Johann Maria Farina, it isn’t hard to give half a dozen ingredients that are almost certain to be in the Eau Sauvage formula. Basically, colognes blend oils of citrus peels with oils of herbs from the mint family. Oils of bergamot, lemon, neroli, lavender, rosemary, and petitgrain are probably in Eau Sauvage.

The bergamot orange is a misshapen, greenish-rust variety of the bitter orange. The bergamot orange is not eaten, but the oil flavors some candy and prepared foods. Bergamot oil is a universal ingredient in cologne and, along with lemon oil, seems to be responsible for the sharp, refreshing character of Eau Sauvage.

Neroli oil is the distilled essence of bitter orange blossoms; petitgrain is distilled from the leaves and twigs of the same tree. The pine or forest note in Eau Sauvage is probably from rosemary, not pine. Rose oil figures in some cologne formulations. If it is in Eau Sauvage, it is only a bare trace.

Cologne’s relative cheapness is due to its dilution. Typically, about 7 grams of essential oils are used per liter of finished product. The rest is alcohol, water, and in some cases orange flower water or rose water. Assuming Eau Sauvage is of typical cologne strength, the 1.9-fluid-ounce bottle contains a scarce 0.39 gram of essential oils. That’s about eight drops.

Reputedly, the best colognes are made from potato alcohol. Many modern perfumers dispute the importance of potato alcohol—alcohol should be alcohol, regardless of source. Better colognes are distilled, with the neroli oil and additional alcohol added after distillation. One to six months’ aging is often recommended in standard formulas. As one of the most expensive men’s colognes, it is likely that Eau Sauvage undergoes aging before being marketed.

Is the greenish-straw color natural? Some cologne essential oil mixtures have an amber color not too different from Eau Sauvage’s, but the color is lost upon dilution to final strength. Like the perfumes that follow, Eau Sauvage has had a dye job.

The big secret here is synthetics. Chanel No. 5 was the first successful perfume to exploit fully a group of chemicals called fatty aldehydes. Despite the unpromising name, fatty aldehydes have revolutionized perfumery. They are usually denoted by the number of carbon atoms they contain—C10, for instance, or C12. Each aldehyde has a distinctive odor that often suggests some natural fragrance. Believed to be in Chanel No. 5 are:

C9—to chemists, n-nonylaldehyde—a liquid with a pleasant rose odor. Chemical formula: CH3(CH2)7CHO.

C10, or n-decylaldehyde, with a sweet odor unlike that of any natural flower. Chemical formula: CH3(CH2)8CHO.

C11, or n-undecylaldehyde, with a strong rose odor. Chemical formula: CH3(CH2)9CHO.

C12, of which two distinct forms may be used. Lauraldehyde [CH3(CH2)10CHO] is a solid with an unpleasant, greasy odor. Diluted, the odor is agreeable. Methyl nonylacetaldehyde [CH3(CH2)8CH(CH3)CHO] suggests a mixture of orange blossoms and ambergris.

There may be a synthetic vanilla note from vanillin or from coumarin. A likely natural oil is ylang-ylang, produced from the sweet, powerfully scented blossoms of a tree of the same name grown in Madagascar and the West Indies. There seems to be a woody component to Chanel No. 5. This could come from sandalwood, a parasitic tree from the Orient, or vetivert, a grass with aromatic roots. A trace of citrus oil may be present. As mentioned, Chanel’s animal note is from civet.

The Missonis know sweaters, not perfume. Not surprisingly, the Missoni fragrance is simply a workmanlike retread of an old standard—the chypre fragrance. Chypre is the generic name for a type of perfume that originated on the island of Cyprus (Chypre to the French) by the twelfth century. Chypre perfumes are heavy, woody/spicy scents. There is less of a flowery character than with most perfumes. Missoni is not the only chypre scent on the market—though it seems to be the most expensive and, one would hope, one of the best made. Aramis and Miss Dior are also chypre scents. Chypre is popular with both sexes.

The three indispensable components of the chypre scent are oakmoss, patchouli, and sandalwood. Vetivert oil is usually present. (Missoni admits to “patchouli, vetivert, and spice” in an ad.) Oakmoss is a lichen—a gray-green encrustation that grows on the bark of oak and plum trees in the Mediterranean region. It is collected, made into an extract, and sold to perfumers and soap-makers wanting a woodsy scent. Patchouli is a shrubby Indonesian mint. Its fragrance suggests both mint and sandalwood. True sandalwood enters into perfumes as an essential oil produced largely in India.

Like other modern chypre perfumes, Missoni seems to have a slight citrus note, perhaps from bergamot. There may be traces of jasmine and rose (probably natural) and vanilla (probably synthetic). Nearly all chypre formulations contain synthetic musk—nonanimal substances such as “musk ambrette,” “musk ketone,” and “musk xylene,” which simulate the character of musk.

Once hailed as the world’s most expensive perfume, Bal à Versailles now undersells several of its competitors. There seems to be little argument as to the main components of Bal à Versailles’ floral bouquet. They are jasmine, ylang-ylang, patchouli, and vanilla. Ylang-ylang oil is sold in two grades, “Ylang No. 1” and “Ylang No. 2.” Presumably Jean Desprez springs for the better Ylang No. 1. But there is scarcely any difference between natural vanilla and synthetic vanillin, so even Bal à Versailles may contain the cheaper synthetic.

Bal à Versailles’ scent is relatively easy to simulate. Many perfume houses offer Bal à Versailles knock-offs. This is done with other perfumes, of course, but Bal à Versailles imitations are often particularly convincing. Some savvy shoppers are convinced that one of these reproductions—“Naudet No. 3,” sold by Essential Products Co. of New York—is slightly better than the original. Naudet No. 3 sells for $16 per ounce.

For a flavor of the perfume industry doubletalk on pricing, consider: For years, Patou has advertised its Joy perfume as the “costliest” fragrance in the world. Joy costs $175 per ounce. But Patou also makes 1000 perfume—and 1000 costs $245 an ounce. When challenged, Patou management is said to allow that 1000 is indeed more expensive but insist that Joy is still costlier. The distinction, at least in Patou’s dictionary, seems to mean that the ingredients of Joy cost more than those of the more expensive 1000. In other words, the markup on 1000 is a lot more. Perhaps to justify its “costlier” ingredients, Patou also offers Joy in a Baccarat crystal bottle for $400.

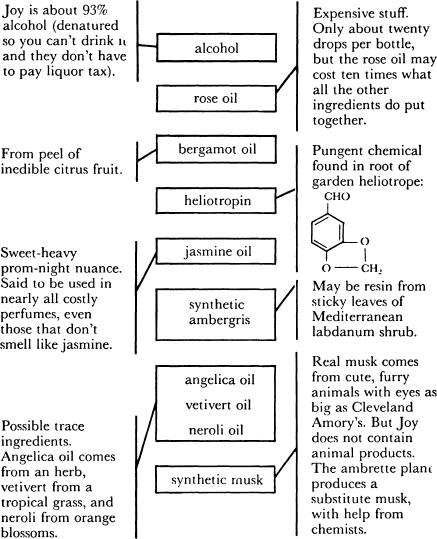

Joy is nothing more nor less than a very well-made rose perfume. High-quality natural rose oil is undoubtedly the main fragrance ingredient. The other ingredients merely gild the lily—make Joy smell more like a rose ought to smell than a rose does. These ingredients may include bergamot oil, heliotropin (a synthetic suggesting evergreens), and jasmine.

Patou says Joy contains no animal products, so evidently an ambergris substitute is used. One of the most satisfactory is a resin obtained from the Mediterranean labdanum shrub. The sticky, fragrant resin coats the leaves. It is boiled off, extracted with a solvent, or, in the case of a Cyprus variety of the shrub, combed from the wool of sheep or goats that graze among the bushes. It smells like balsam.

The ingredient list on the following page is from a recipe for an imitation of Joy perfume in A Formulary of Cosmetic Preparations by Michael Ash and Irene Ash (New York: Chemical Publishing Co., 1977). That recipe suggests ambergris and musk; synthetics have been substituted here to conform with Patou policy

Patou’s ultrastatus scent, 1000, is less sweet-and-conventional. A strong leafy note suggests a mown lawn, growing plants, or the “weedy” nuances of a Cabernet Sauvignon. Floral notes are muted.

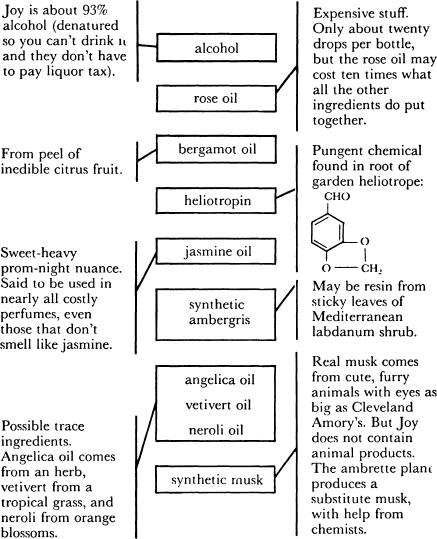

There’s no grass in 1000. Perfumers create the mown-lawn effect with two substances, coumarin and linalool. Coumarin can be extracted from the tonka bean, the seed of a South American tree. Coumarin is toxic and not permitted as a flavoring in the

United States, but it is used in perfumes. Coumarin’s chemical formula is:

Linalool is present in bergamot oil. Its formula is:

CH2:CHCOH(CH3)CH2CH2CH:C(CH3)2

The floral background of 1000 seems to include natural rose and jasmine oils. Violet and tuberose—natural or artificial—may be present.

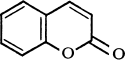

One of the reasons for all the secrecy is the cost. Once the ingredients of a perfume are known, the cost of raw materials can be estimated. In most cases, this cost is a small fraction of the retail sales price—a fact of life in the fragrance industry but one they’d prefer not to publicize.

This is not to say that perfume manufacturers are making a killing. The actual profit to manufacturer is a small part of the gaping difference between ingredient costs and sale price. Manufacturers of fragrances tied to a designer name pay a royalty to the designer (who rarely gives more than a name to the creation). There is often an under-the-table spiff paid to department store salespersons to push a perfume. Bottle and packaging are expensive (if not always to the tune of the $225 you pay for the Baccarat crystal bottle of Joy). Promotion and assorted overhead expenses make up the rest. A 1974 New York Times article drew industry ire for estimating these expenses for a then-costly $35 bottle of perfume. The Times analysis claimed the following breakdown (here converted from dollar amounts to percentages):

Many perfume ingredients are fabulously expensive. The best floral essences can cost $2,000 a pound or more; musk costs about $12,000 a pound. But in most cases a little goes a long way.

Take the Formulary of Cosmetic Preparations recipe for imitation Joy. It is hard to say how closely it matches Jean Patou’s formula for Joy. However, most perfumes are blended at roughly the same fragrance strength. Joy could hardly contain much more essential oil than specified in the imitation recipe. Moreover, the formulary recipe uses good, expensive ingredients. If the required amounts of ingredients are multiplied by the prices, the results are the ingredient costs—for the imitation Joy, at any rate.

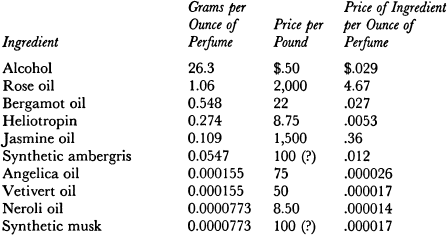

The ingredient prices below are typical. Prices vary according to quality, amount purchased, and market fluctuations. Actual amounts of synthetic ambergris and musk might have to be juggled according to the strength of the substitutes.

Only five ingredients contribute so much as a penny to the final per-ounce cost. The total per-ounce cost: about $5.15, most of it for rose oil.