It is not easy to design cheatproof playing cards, if possible at all. Most card manufacturers do not even try. Cheaters, however, are aware of the back design as a security device. With certain back designs, it is more difficult to bottom-or second-deal undetected than with other designs. Some backs are easier to mark than others.

For bottom-or second-dealing, the ideal deck would be onewith a solid-color back. With such a deck it would be hard for the other players to tell whether the top card is sliding forward and off the deck (as it should in a legal deal) or staying on top (as in a bottom-or second-deal).

None of the readily available brands of cards has a solid-color back. In practice, bottom-dealers favor brands with small, regular patterns—patterns that are just a blur of color in a brisk deal. Diamond-pattern Bee (back no. 67) and Club Reno are examples.

A white margin ruins a deck for bottom-dealing. As the bottom (or second) card is drawn out, the other players see its white margin, then part of its back pattern, then the top card’s white margin, and then the top card’s back pattern. This is different from what they see when the top card is drawn off fairly. So decks such as Aviator and Bicycle are relatively cheatproof as far as bottomdealing is concerned.

Likewise, any conspicuous, localized design works against bottom-dealing. A prominent design acts as a landmark to help players judge whether the top card is removed. It’s best if the design is a different color, such as the logos on some airline and promotional decks. Many Las Vegas casinos use custom Bee decks overprinted with the hotel logos.

Gambling lore favors a United Airlines giveaway deck as the most cheatproof. Flight attendants offer the deck (in first class) or supply it if you know enough to ask for it (in coach). Although manufactured by the U.S. Playing Card Company, the deck is in some ways more secure than that company’s popular retail decks. The back design is a solid color except for two United Airlines logos. The white logos make it relatively easy to spot bottom-dealing. The simplicity of the back design makes it nearly impossible to mark the deck. Many other airline decks are equally good.

Any complex back design may be marked. One of only two ink colors—navy blue or medium red—will suffice for the well-known U.S. Playing Card brands. The trouble with marking cards at home, however, is that the deck’s seal must be broken.

Premarked cards, favored by serious players, come from Louis Tannen, Inc., a New York magic supply house. Tannen’s marked decks are genuine U.S. Playing Card decks that have beenopened, marked by hand, and resealed with a duplicate U.S. Playing Card stamp, cellophane wrap, and a white tear-band bearing the brand name. Each deck comes with separate instructions for decoding the markings. Big Secrets ordered Tannen’s Aviator, Bee, and Bicycle decks to see how the markings are concealed.

Aviator

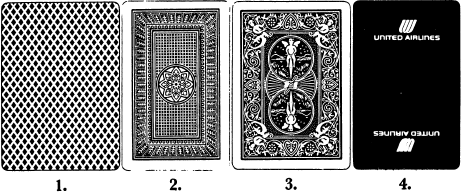

The markings are along the top margin of the back pattern. Ten “sprout” designs run across the top. The two center sprouts encode the rank. Each sprout has six leaves. One of the leaves is disconnected from the sprout—with a dab of ink—to signify ranks 3 through ace. The leaves on the left side of the left center sprout signify ace, king, and queen, from top to bottom. Leaves on the right side of the left sprout are jack, 10, and 9. Similarly, the right center sprout encodes 8, 7, and 6 and 5, 4, and 3. If no leaf is disconnected, the card is a deuce.

The three sprouts to the left of the center sprouts give the suit. The “bud” at the top of the sprouts is half blocked out to signify (left to right) diamonds, clubs, and hearts. If all the buds are entire, the card is a spade. All the markings are repeated at the bottom, of course, so the cards may be read from either end.

Bee

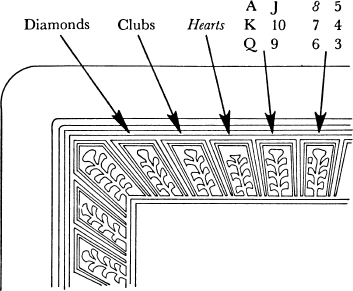

On all Bee cards, a column of diamond designs runs just inside the right margin. The top three complete diamonds encode the rank. Look at the uppermost of the three diamonds. A triangular extension of dark ink on the right side of the top point of the diamond means ace. A marking on the top left side means king. Similar markings on the bottom point mean queen (bottom left) and jack (bottom right). The diamond below this one encodes 10, 9, 8, and 7; the diamond below that is for 6, 5, 4, and 3. Deuces are not marked.

Above and to the left of the upper diamond is another complete diamond. It is for the suits: Top right is diamonds, top left is clubs, and bottom left is hearts. Spades are not marked.

Bicycle

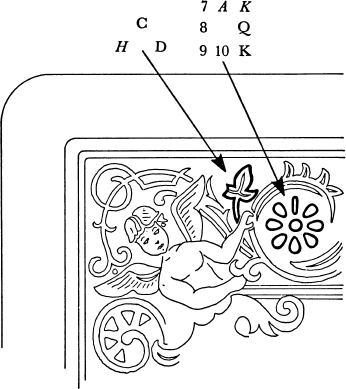

Find the angel in the upper left corner. His left hand rests on a vine that encircles an eight-petal flower design. The flower gives the rank. When the upper (twelve o’clock) petal is narrowed, the card is an ace. Going clockwise, the position of the narrowed petal signifies king (one-thirty), queen (three o’clock), jack (four-thirty), ten (six o’clock), nine (seven-thirty), eight (nine o’clock), and seven (ten-thirty). For lower ranks, the inner tip of the petal is inked out. A truncated petal at twelve o’clock is six; three o’clock is five; six o’clock is four; nine o’clock is three. All the petals are left entire for a deuce.

Above the angel’s arm is a three-part leaf. When the outer, left tip of the leaf is marked out, the card is a heart. The central, upper tip is for clubs; the inner, right tip is for diamonds; no marking signifies spades.

With sharp eyes the Bicycle and Aviator markings can be read passably well at arm’s length. The Bee markings are slightly more difficult to read. Persons aware of the markings but not of their precise location may take several minutes to find the marks.

Chapter 54 of Tom Robbins’ 1980 novel, Still Life with Woodpecker, describes a fantastic “hearts and diamonds bomb”:

Take a deck of ordinary playing cards, the old-fashioned paper kind, cut out the red spots and soak them overnight like beans. Alcohol is the best soaking solution, but tap water will suffice. Plug one end of a short length of pipe. Pack the soggy hearts and diamonds into the pipe. On pre-plastic playing cards, the red spots were printed with a diazo dye, a chemical that has an unstable, high-energy bond with nitrogen. So you’ve got nitro, of sorts, now you’ll be needing glycerin. Hand lotion will work nicely. Glug a little lotion into the pipe. To activate the quasi-nitroglycerin, you’ll require potassium permanganate. That you can find in the snakebite section of any good first-aid chest. Add a dash of the potassium permanganate and plug the other end of the pipe. Heat the pipe. A direct flame is best, but simply laying the pipe atop a hot radiator will turn the trick. Take cover!

In the context, most readers dismiss this as whimsy. But the hearts and diamonds bomb and the other bombs Robbins describes are real. Similar bomb recipes appear in William Powell’s The Anarchist Cookbook, an underground weapons manual.

What Robbins calls the “jug band bomb” is a working homemade bomb. It is a glass jug containing a few drops of gasoline. The jug is capped and turned around so the gasoline coats the inner surface and evaporates. A few added drops of potassium permanganate solution make the gasoline vapor/air mixture all the more explosive. The bomb is detonated by throwing or forcibly rolling against a wall.

Whether the hearts and diamonds bomb would work is debatable. Robbins makes certain substitutions in the usual recipe: hand lotion rather than pure glycerin, a snakebite nostrum rather than a potassium permanganate solution of known strength.

Assume then that pure glycerin and potasssium permanganate are used. You might get a bomb by mixing diazo compounds with glycerin and potassium permanganate. The question is how much diazo dye could be extracted from red card spots.

The staff historian for the U.S. Playing Card Company admitted hearing of the bomb stories but was not aware of any working bomb having been constructed. In any case, the main problem with the recipe is that there is nothing “ordinary” about old-fashioned paper playing cards. Effectively all cards are now plastic-coated.