Two of David Copperfield’s best-known illusions are levitations of inanimate objects. One uses a large, metal-finish ball, which floats about the stage on command. At one point Copperfield passes the ball through his arms to demonstrate that no wires are used. The other effect, used in a TV commercial for Eastman Kodak, involves a knotted handkerchief. The handkerchief “dances” and jumps from hand to hand. When stuffed in a stoppered glass bottle, the handkerchief thrashes as vigorously as before. It “struggles” to get out and soon pops the stopper and jumps out.

Not only do both tricks seem to rule out all conventional means of support, but also the control of the floating objects is remarkable. Copperfield balances the seemingly heavy ball on a fingertip. It follows a slow, controlled arc to the other hand. The ball retreats from Copperfield, and then it comes back on command. The handkerchief becomes a puppetlike animation.

With cruder forms of levitation, it is a simple matter to decide who is controlling the object: the magician or an unseen flunky offstage. When the magician is in control, the object can strut like a marionette, but—surprise, surprise—it never strays more than an arm’s length from the magician. As much of the audience gathers, the object is a marionette, just with extra-thin strings. When controlled offstage, the object can vary its distance from the performer and even rise above his head. But movements are slow and awkward. If moved too quickly, the object tends to develop a giveaway sway. Copperfield’s method is so much more impressive that some postulate a novel technology—focused air currents or magnetic fields, say.

Copperfield is not the only magician to perform these illusions or variations of them. Mark Wilson first performed the floatingball trick on national television. Doug Henning levitated an “enchanted silver sphere” in a 1982 TV special and a lighted candle in his Broadway musical, Merlin. Larry Wilson performs the dancing-handkerchief trick, with the handkerchief jumping in and out the doorways of a small wooden cabinet. In all cases, the method appears to be the same as Copperfield’s.

The larger magic catalogs offer two illusions purporting to levitate a metallic ball. The simpler of the two is sold under the trade name Zombie. The Zombie illusion uses a lightweight, metal-finish ball with a secret hole. A cork fits snugly into the hole, and the cork is attached to one of the performer’s fingers by a stiff wire. By moving the finger, the performer moves the ball. But the performer must always drape a cloth over or near the ball to hide the wire support. The ball may never vary its distance from the finger supporting it—and this distance is only about a foot.

With practice, the Zombie illusion is not as transparent as it may seem when described. It has the advantage of not requiring an elaborate setup. No amount of skill can conjure away the need for the cloth to conceal the wire support, however. Copperfield does not use a cloth with his floating ball.

The second illusion is described in “The Don Wayne Floating Ball,” a manuscript sold by Louis Tannen, Inc. and other magic materials suppliers. It is a far superior illusion to Zombie, and it is the method Copperfield uses—the manuscript acknowledges that Copperfield and Mark Wilson use it.

The ball is about eight inches across. It is hollow. It may be made of aluminum, acrylic, papier-mâché, or a lightweight plastic. In all cases, it weighs far less than its metal surface suggests.

Size A black silk thread suspends the ball. The average audience little appreciates how invisible a thread may be. For levitations of very small objects, magicians sometimes use a fine nylon that can be invisible at close range in full sunlight to a person of normal vision (they attach bits of adhesive wax to the ends so they will be able to work with it). Size A silk is visible from severalyards, but this is remedied by careful choice of lighting and backdrop. If both the silk and the backdrop are black, the silk is very hard to see. The mirrored ball serves a double purpose. It makes the audience think that the ball is quite heavy and thus that any supporting threads would have to be good, thick, and visible. Also, the spotlight play on the ball’s mirror surface blinds the audience to the dark threads.

(It doesn’t always work that way. On “Doug Henning’s Magic on Broadway,” an NBC special broadcast November 14, 1982, the thread was visible several times—on home TV screens, yet—as Henning performed the illusion.)

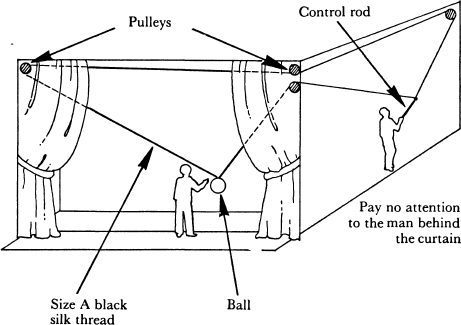

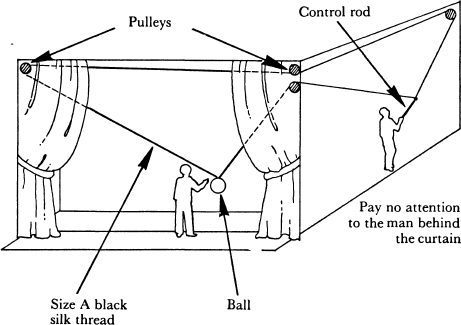

An astute observer might notice that the ball’s mobility is limited to a plane. As usually set up, the plane is parallel to the backdrop. It passes through, or just in front of the performer. The diagram shows why.

The ball is supported by two threads coming from upper stage right and upper stage left. The two threads and ball actually are part of one continuous loop. At upper stage left, the thread passes over a pulley and then backtracks high over the performer to upper stage right. There it makes a ninety-degree turn over another pulley and passes over an offstage assistant to a pulley far offstage. There it angles down to the assistant, back up to a second pulley at upper stage right, and back to the ball.

Offstage, the thread is tied to an eyelet at the end of a rod held by the assistant. The motions of the eyelet in its plane correspond to the motions of the ball in its plane, with one difference: Vertical motions are reversed. Moving the eyelet up increases the slack in the thread and causes the ball to drop. Moving the eyelet down raises the ball. The ball-bearing pulleys ensure that the ball drops evenly and not from one side only. Horizontal motion of the eyelet moves the ball in the same direction.

The assistant is situated so that he can see the performer at all times. The backdrop may be partially transparent so the assistant can see the spotlighted performer and ball but the audience can’t see the assistant in the shadows. Or ordinary curtains may block audience view of the assistant. Because the assistant is watching the performance in real time, he can control the ball almost as well as the performer himself could. Maneuvering the ball with the control rod becomes natural after a little practice. To make the ball jump from the performer’s right hand to left hand (move from nine o’clock to three o’clock, clockwise, as seen from the audience), the assistant must swing the control rod eyelet in an arc from nine o’clock to three o’clock counterclockwise, as seen from far stage right.

The beauty of the trick is that no one expects threads to be diagonal. The magician can wave his hands above the ball, below it, and to either side. As far as most of the audience is concerned, this rules out the possibility of threads.

The ball cannot, of course, be passed completely through a fair vertical hoop. The illusion manuscript advises the performer to form his arms into a circle to one side of the ball, with the thread already passing through the arms. The ball can then be directed horizontally through the linked arms. Close observation of Copperfield and other performers shows that this is indeed what they do. If the performer wants to use a metal hoop, it must have a small break for the thread to pass through.

Small objects other than a ball may be levitated as well. Henning’s burning candle seems to use the same setup as the floating ball. In principle a. handkerchief (perhaps containing a lead weight for stability; might be levitated in an identical manner. As performed by Copperfield, Larry Wilson, and others, however, the handkerchief trick has some additional features.

Occasionally the handkerchief is borrowed from an audience member. Even if the audience member is a confederate with a prethreaded handkerchief, the threads should be difficult to conceal from those sitting nearby.

Unlike the floating ball, the handkerchief frequently darts in and out of closed containers. It continues to move inside the containers.

The secret is to be found in another illusion manuscript, “Harry Blackstone’s ‘Spirit Dancing Handkerchief,’ “available from Abbott’s Magic Manufacturing Co. The illusion, including the routines with the glass bottle and the cabinet, was devised by Harry Blackstone (father of the Harry Blackstone, Jr., now performing). It requires two assistants.

At the beginning of the trick, a size “O” silk thread stretches across the stage at waist height. Each end is held by an offstage assistant.

The magician borrows an unprepared handkerchief from someone in the audience. Going back onstage, he ties a knot in the handkerchief—tying it around the thread. (The magician must turn his back to the audience as he does so, or the assistants must lower the thread briefly so that the magician can step over it and face the audience.)

The handkerchief is subsequently animated by the two assistants working in unison. The manuscript recommends red lights (to make the thread invisible) and a second thread lying on the floor in case the first one breaks.

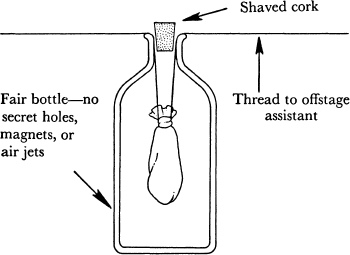

The only preparation needed for the glass bottle is to shave about one-quarter to three-eighths inch from two opposite sides of the cork. After the handkerchief is placed in the bottle, the stopper must be aligned with the flat sides pointing to the assistants. This allows free space for the thread to slide smoothly over the glass. When inside the bottle, the handkerchief can jump up and down, but it must stay directly under the cork. The cork must, of course, fit very loosely for the handkerchief to pop it off.

The cabinet works the same way. Its edges must be rounded so the thread does not catch. The magician may stuff the handkerchief in one opening and pull it out through another. When the assistants then both pull on their ends of the thread, the handkerchief enters the cabinet through the latter opening, peeks out the first opening, and then jumps out.

At the end of the performance, the magician holds the handkerchief in one hand. One assistant lets go of his end of the thread. The other pulls. The thread slides through the handkerchief knot and is reeled in by the assistant. Meanwhile, the magician places his thumb behind the handkerchief knot and reanimates the handkerchief. It seems to be struggling to free itself. The magician walks out into the audience (which he couldn’t do during the performance) and hands the handkerchief back to its owner.