Harry Blackstone, Jr., performs the most spectacular of the sawing illusions: He saws through a woman, in plain view, with a buzz saw. The saw looks and sounds real. It cuts through wood. A woman lies down on a platform close to the blade. Unlike other sawing illusions, no cabinet is used. The blade visibly slices through the woman’s torso, shredding part of her dress. Even during the sawing, the head and legs move naturally. What makes this illusion so baffling is that there seems to be no room for deception. The audience sees everything, and what it sees is impossible.

Blackstone’s buzz saw is, of course, a refinement of the basic sawing-a-woman-in-two illusion. The sawing illusion has been performed in various ways by various magicians ever since 1921. Sexism, not anatomical constraints, dictates that a woman be used. Horace Goldin, who pioneered the trick in the 1920s, originally used a male subject.

Goldin’s precise method is no matter of conjecture: He patented it in 1923. If you write the U.S. Patent Office and request patent number 1,458,575, they will send a complete description, including diagrams for construction of the cabinet.

A large, rectangular cabinet rests on a table. The cabinet may be lifted off the table and shown at various angles. The top of the cabinet unhinges. A woman gets into the cabinet, possibly assisted by audience volunteers. One end of the cabinet has three openings, for the woman’s head and hands. The opposite end has two openings, for her feet. Once the woman’s extremities are in place, the top of the cabinet is closed and padlocked. The cabinet may again be lifted to demonstrate that the woman is completely inside. The cabinet is replaced on the table, and the table is spun around to show the apparatus from all angles.

Using a large, genuine saw, the magician and an assistant cut through the cabinet at its center. The cabinet is usually presented to the audience lengthwise so that the woman’s head, feet, and hands are visible at all times. If desired, audience volunteers may secure the woman’s extremities during the sawing.

The saw is withdrawn. Two metal plates are fitted into preexisting slots just on either side of the cut. The two halves of the cabmet are pulled apart. The metal plates prevent the audience from seeing the (presumably bloody) results of the sawing. The magician points out the head, hands, and feet, which are still moving and obviously not fakes.

Then the two halves are shoved back into contact. The metal plates are removed, the padlocks are unlocked, and the top is opened. The woman steps out of the cabinet, uninjured and in one piece.

Goldin’s trick uses two women. The second woman is hidden in the thickish tabletop on which the cabinet rests. Unknown to the audience, the bottom of the foot half of the cabinet has a pair of trapdoors that open upward only. The tabletop has a matching pair of doors. The two pairs of doors must be perfectly aligned. When the cabinet is lifted and replaced on the table, wood ridges on the tabletop help the magician position the cabinet correctly. As the magician spins the table, the feet point away from the audience for a moment. The first woman quickly pulls in her legs, resting her feet on a footrest built into the head half of the cabinet. This places the first woman entirely in the head half. The second woman opens the trapdoors and sticks her feet out the two openings in the end of the cabinet.

The box can then be sawed without harm. The metal plates prevent the audience from glimpsing the illusion’s inner workings. Because of the trapdoors, only the head end can be moved.

Rejoining need take only a few seconds. The magician slides the head half back into place and removes the metal plates. One plate is casually propped against the cabinet in such a way as to block the audience’s view of the feet. The two women switch feet as the magician unlocks the top of the cabinet.

An extra touch, created by Howard Thurston, has the magician snip off part of the woman’s sock before the sawing. The magician pretends to hear a heckler protest that the feet are not real. “Spontaneously” he removes the woman’s shoes, cuts off part of one sock, and asks an audience volunteer to testify that the foot is real. The second woman, of course, must wear a sock cut in the same manner. Thurston also had volunteers hold the woman’s head and feet during the sawing. The person holding the feet was a confederate.

All modern magicians are haunted by the ghost of Goldin’s second woman. Word of the second woman leaked out. Sophisticated audiences now expect there to be two women. In consequence, the two-woman method has become operationally extinct. (Abbott’s Magic Manufacturing Co. sells a workshop plan for Thurston’s method, but none of the well-known contemporary performers dares use it.) The voluminous cabinet and thick tabletop are passé. The modern sawing illusions are designed to banish any suspicion of a second woman.

The method used by Doug Henning in Merlin comes closer to the ideal of a visible sawing. A cabinet is still used, but it is a thin cabinet (about twelve inches thick vs. more than eighteen inches for the old method). Skeptics must concede that even a contortionist cannot draw her knees up under her chin in a foot of crawl space. With the Goldin/Thurston method, the tabletop had to be thick as well. Henning’s tabletop is about two inches thick.

The basic scenario is the same, with one innovation: two small doors in the front of the two halves of the cabinet. These may be opened to show the audience the cabinet interior. The cabinet top is opened, and the woman gets in. Stocks secure the head and feet (the arms are inside the cabinet). The two side doors are opened to show that the woman is indeed in the cabinet. The door in the head half shows the woman’s arm and torso; the door in the foot half reveals her legs. The woman may stick her arm through the doorway and wave to the audience. The feet move as well. The doors are closed.

The cabinet is sawed through its center. Two metal plates go on either side of the cut. (In Henning’s performance, the plate in the head end fails to go down all the way. Henning pulls on the woman’s head, and the plate falls into place.) The two halves can then be separated. (The table is in two parts, each with three legs.) The halves may be shown from all angles.

The climax comes when the side doors of the disconnected halves are again opened. The woman’s body is seen to be in the same position. Even a spectator thoroughly familiar with the Goldin/Thurston method is likely to conclude that the cabinet affords no room for a second woman and no room for the woman to scrunch up her body in some position other than where it seems to be.

The only thing suspicious about the setup is the triangular arrangement of the table legs. After all, everyone knows about those triangular tables with mirrors between the legs. But this suspicion doesn’t pan out. When Henning or an assistant stands behind one of the table halves, their legs are visible underneath it. There are no mirrors.

In due course, the halves are reassembled, and the woman emerges whole. (In Merlin, Henning sawed two women in half and interchanged their halves.)

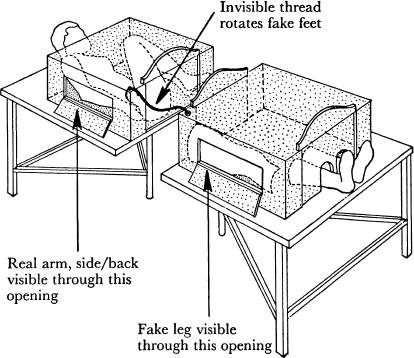

Henning’s secret is revealed in a workshop plan titled “Thin Model Sawing A Woman In Half” and available from Louis Tannen, Inc. Henning’s use of the “Thin Model” method is mentioned in the plan. Only one woman is used. In brief, the gimmicks are fake feet and a cabinet that is wide enough for the woman to pull up her knees sideways.

According to the plan, the cabinet is 24½ inches wide. This allows just enough space for a slim woman to draw her legs up to her side. The legs are drawn up on the side away from the side door, of course. The woman’s head remains facing upward.

The foot half of the cabinet is equipped with a set of mannequin feet. As soon as the woman gets in the cabinet, she draws herself up into the head half and pushes the fake feet through the opening at the foot end of the cabinet. (This action is in part concealed by the open doors on top of the cabinet.) The woman’s real feet are never seen once she gets in the cabinet. The audience sees two feet emerge from the end of the cabinet and assumes them to be the woman’s.

The feet must move to be convincing. They have two degrees of freedom. A slide mechanism with a leather grip lets the woman control the in-and-out motion (while the two halves of the cabinet are together). The feet are also on hinges that allow them to rotate inward and outward. This motion is controlled by an invisible monofilament thread operated by the woman or an offstage assistant. A spring attached to the hinges provides a restoring force to counter the string. From a distance, these two motions are sufficient—unless a heckler asks the woman to wiggle her toes.

The open side doors provide but a limited view of the interior. In the head section, you see a genuine arm. Behind it is the woman’s costume covering what you take to be her side. Actually, it’s the woman’s back. The leg in the other side doorway is a built-in fake. It conceals the rotating feet mechanism.

For Henning’s shtick with the metal plate, the woman evidently blocks the blunt plate with a hand or her feet until the right moment.

Could fake legs likewise explain Blackstone’s buzz saw illusion? The main objection is that there seems to be no opportunity to switch the real legs for the fakes. The woman lies down in full view. The legs are never out of sight. The same is true for the head.

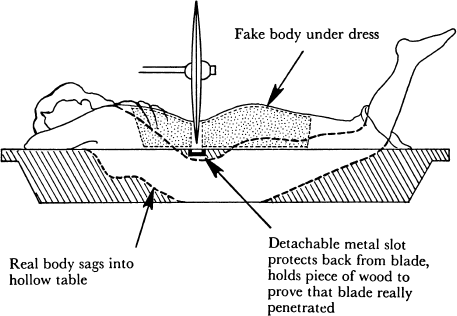

The real secret, as explained in Abbott’s “Buzz Saw Illusion” manuscript, is more ingenious yet. Both the head and legs are real. What is fake is the body. In effect, the buzz saw illusion uses a “cabinet” that is shaped like the woman’s torso.

The illusion’s wood structure incorporates a buzz saw and a mobile table. By means of a crank, the table can be moved under and past the blade of the stationary saw. The table surface hides a large rectangular depression (about 28⅞ inches long by 13½ inches wide by 7¼ inches deep). But the table is just about at audience eye level, so the depression is not noticeable.

As a preliminary demonstration, a strip of wood is secured to the table with a metal holder. The wood and holder bridges the hollowed-out part of the table. Unknown to the audience, the wood has been precut most of the way through. The uncut side is up. The buzz saw is switched on, and the table is drawn under the blade. When the wood is removed, it breaks easily in two.

Under her dress, the woman wears a strip-metal framework conforming to the back of her torso. This is secured with snaps on the abdomen side. The framework includes a strip of flesh-colored cardboard near the intended site of the cut.

As the woman lies down on the table, the billows of her dress—and a conveniently placed assistant—prevent the audience from seeing what is going on. The woman unsnaps the framework. Her midsection sags into the hollow. The framework, held in place by projections, seems to rest on a flat table.

As a safety measure, the magician and his assistant reinsert the metal holder and a new wood strip “under” the woman’s body. Ostensibly this is so the wood will be sawn in two and can be offered as evidence of penetration. Actually, the wood and metal holder go just over the woman’s back, through a slot in the torso framework. The wood and metal thus protect the woman’s back from the blade.

The swayback position is awkward but safe Because the fakebody is cloaked in the dress, it does not have to be as well crafted as the fake legs in the “Thin Model” sawing illusion. By and large, audience suspicion is directed to the head and legs, which are genuine. The pink cardboard “back” does not bear close examination, but it is covered up with a cape as soon as the blade is clear. The Abbott’s plan recommends dim lighting and a red spotlight on the woman.

If there is any danger to the illusion, it is incidental. The plan warns to take care that the woman’s hair does not get caught in the belt driving the blade. The woman must keep her legs vertical, lest they come too close to the blade. The saw is of low power (three-quarter horsepower is suggested). It cuts a dress and pink cardboard but goes through wood with difficulty.