A faked accident draws gasps at the climax of this illusion. As performed in Merlin, Doug Henning rides a small horse into a cratelike structure. (On television, Henning has used a motorcycle.) Initially, the front of the wood structure is open so that the audience can see both Henning and the horse. Four heavy chains slowly raise the structure from the floor of the stage. Henning and the horse are still visible, and the crate is isolated from the floor, the sides of the stage, the backdrop, and the ceiling. There seems to be nowhere for Henning and the horse to go. Then the crate—which looked rickety all along—suddenly collapses. A horse’s muffled whinny is heard—but Henning and the horse have vanished. Only the edges of the crate remain in place; the bottom and back sides dangle below.

A second or two later, Henning and the horse (or motorcycle) are revealed safe in a distant part of the stage or in a separate, suspended frame. The audience is left wondering not only how the trick was done but also how the horse was trained to perform whatever moves may be required of it.

There are only three basic ways to make a person vanish. One is to lower the person through a trapdoor in the stage. The second is to conceal the person with a judicious placement of mirrors. The third is to conceal the person behind a panel or curtain that blends into the background. Henning uses all three methods in his repertoire of illusions.

At another point in Merlin, for instance, Henning sits in a simple chair, well away from the backdrop and sides of the stage. A blue cloth is draped over Henning and the chair. A few seconds later, the cloth is snatched away. Henning is gone. (The chair is still there.) Henning then reappears from another part of the stage.

This effect appears identical to a very old illusion using a trapdoor under the chair. A wire frame maintains the shape of the body in the chair as the performer drops through the seat of the chair (it’s on a hinge) and a trapdoor beneath. The wire frame is drawn away with the cloth.

Use of mirrors was apparent on “Doug Henning’s Magic on Broadway” TV special. Henning made a woman and a million dollars appear and disappear from a transparent cubical box. The box rested on what appeared to be a simple four-legged table. For each appearance and disappearance, the box was covered with an opaque screen.

Anyone familiar with magic would have suspected an “Owens table”—a table with vertical mirrors running between the legs. The mirrors reflect the floor or carpet so that it looks as if you are seeing the carpet under and behind the table. Actually, there is a secret space between the mirrors. The woman and the money could have been hidden in this space to effect a disappearance.

The trouble with the Owens table is that the mirrors must be aligned just right for the perspective of the audience (or TV camera). In at least one camera shot of Henning’s special, the mirrors were noticeably out of alignment. The reflection of the floor was a little higher than the floor itself. This was particularly evident if you looked at the line where the floor met the backdrop. It zigzagged as it went “behind” the legs of the table.

The third method is the simplest, but its use is limited. With suitable misdirection, a person may be hidden behind a panel matching the background. This is just the large-scale version of the false bottom in a magician’s hat. Usually, the edges of the panel must be concealed. Dark colors, dim lighting, and a distant audience are preferred.

If you give the horse-and-rider illusion some thought, you’ll realize that there have to be two horses and two riders. The fake Henning has to be the first one, the one who vanishes. Before the illusion, no one expects a substitution. Henning has opportunity to duck offstage and send in his double. The Henning who reappears, however, has to stand up to the scrutiny of a suspicious audience.

The double used in Merlin is no dead ringer for Henning. As the crate is being raised, he looks away from the audience and waves, raising his arm so that it blocks his face.

Granting the switch, we are still left with an impressive illusion. The rider, who as it happens is not Henning, and the horse, which is alive, genuine, and heavy, both suddenly disappear far above the stage floor. The illusion is again an old one. It was devised by Clayton L. Jacobsen, who called it the “Vanishing Motorcycle and Rider” and explained it in The Seven Circles, a magazine for magicians. The idea of using a horse instead of a motorcycle was likewise Jacobsen’s.

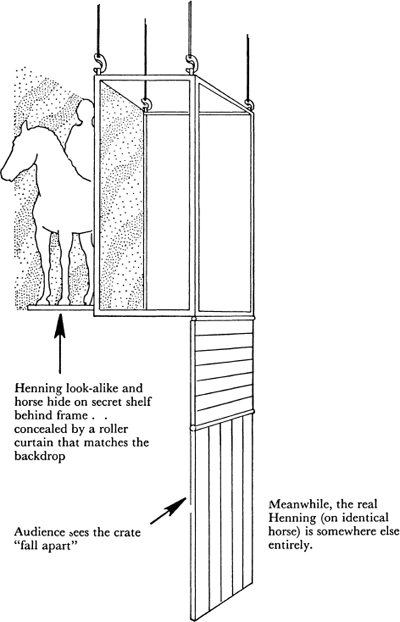

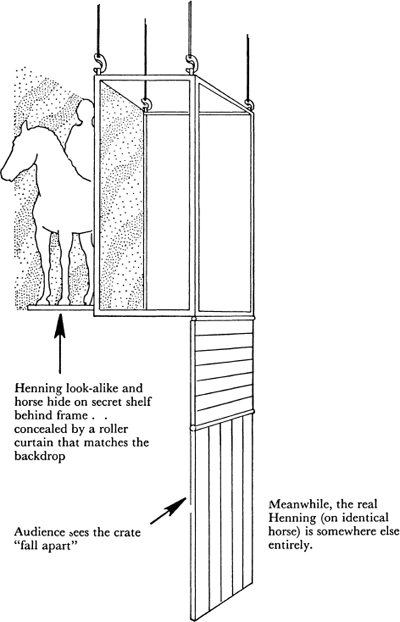

The crate must be sturdy. As the crate is being raised, the front is opened. The front is closed just before the disappearance. The bottom of the crate is equipped with a movable shelf that slides out toward the back (away from the audience). In fact, there is no back to the crate, so horse and rider both slide back the instant they are out of the audience’s sight. A roller curtain made of the same material as the backdrop is pulled down in front of the horse and rider.

Then the crate “collapses.” Actually, the crate edges, the secret shelf, and the curtain remain. The horse and rider are both still up there, behind a curtain that is indistinguishable from the backdrop. (Or, in a variation of the method, the fake backdrop is stretched between two of the supporting chains. Horse and rider are lifted up and out of sight by means of cables and a harness.) The frightened-horse sound is probably a recording. All that either horse must do is stand still and not be frightened by the commotion.

If the audience looked at the crate long enough, they might suspect the false backdrop. But they don’t. Before anyone quite realizes what has happened, the real Henning is revealed—and attention shifts to him.