Sandwiched into the gap between the AM and FM dials are hundreds of secret communications frequencies—some so secret that no one owns up to them. The usual consumer gear—AM/FM radios, TVs, CB radios—brings in only a small portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. To pick up the secret signals, you need a shortwave receiver—and you need to know the unlisted frequencies.

Allocation of radio frequencies is quirky. When you flip the TV dial from channel 6 to channel 7, you unknowingly jump over the entire FM radio band as well as such exotica as Secret Service communications and a special frequency designated for emergency use during prison riots. The U.S. government will provide information on unclassified allocations (those for the Coast Guard, Forestry Service, weather reports, etc.). But it is quiet about secret government frequencies and those of mysterious illegal broadcasters here and abroad.

Many shortwave-radio hobbyists keep track of the secret frequencies, however. Their findings appear in such publications as the Confidential Frequency List by Oliver P. Ferrell (Park Ridge, N.J.: Gilfer Associates, 1982 [periodically updated]), How to Tune the Secret Shortwave Spectrum by Harry L. Helms (Blue Ridge Summit, Pa.: TAB Books, 1981), and The “Top Secret” Registry of U.S. Government Radio Frequencies by Tom Kneitel (Commack, N.Y.: CRB Research, 1981 [periodically updated]). These and similar publications should be consulted for the most up-to-date listings. The selection below includes only the most noteworthy or inexplicable broadcasts.

Many of the in-flight phone calls from Air Force One are not scrambled and can be picked up by anyone with a shortwave radio. You just have to watch the newspapers for information on the President’s travels and listen to the right frequencies shortly before landing or after takeoff at Andrews Air Force Base (when calls are less likely to be scrambled electronically). A presidential phone call is usually prefaced by a request for “Crown,” the White House communications center.

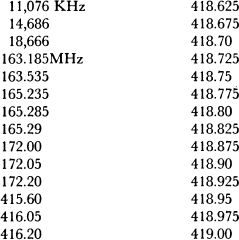

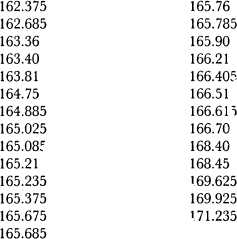

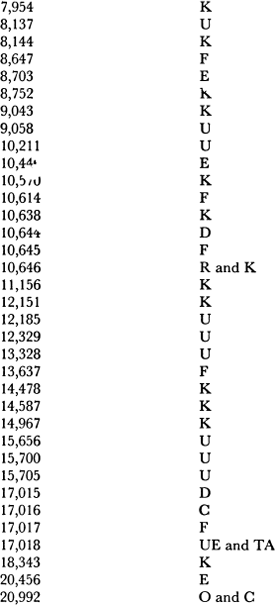

Air Force One uses several frequencies, including those assigned to Andrews Air Force Base. Transmissions are on single, usually upper, sideband. The frequencies are nominally secret, but the frequency numbers have long since leaked out or have been discovered independently. It is suspected that wire services and TV news operations monitor them for leads. The reported frequencies (in kilohertz) are:

In addition, 162.685 MHz and 171.235 MHz are Secret Service frequencies used for Air Force One communications. The White House staff uses 162.850 MHz and 167.825 MHz. Secret Service channel “Oscar,” 164.885 MHz, is used for the President’s limousine. Air Force Two uses the same frequencies as Air Force One.

Although everyone concerned must know that outsiders may be eavesdropping, conversations are often surprisingly candid. (Shortwave-radio listeners heard the White House staff urging Air Force Two back to Washington after the 1981 attempt on President Reagan’s life, complete with reports that then-Secretary of State Alexander Haig was “confusing everybody” with his claim of being “in control.”) No law seems to forbid such eavesdropping. Ironically, it is illegal (Section 605 of the Communications A.c. of 1934) to reveal intercepted conversations to anyone elsethat being regarded as the wireless equivalent of wiretapping Even so, The New York Times has run snippets of Air Force One con versations.

The CIA and other government agencies with clandestine operations are believed to have dozens of authorized frequencies, which may be rotated as needed to throw eavesdroppers off the track. Call letters are rarely used, and several government agencies may share the same frequencies. A further, rather thin veneer of security comes from the use of code words. Government surveillance operations use a common code: “Our friend” or “our boy” is the person being followed. “O” is his office; “R” is his residence. A “boat” is a car. Once apprehended, a suspect is a “package” and may be taken to the “kennel,” the agents’ headquarters. Does this fool anyone? Probably not.

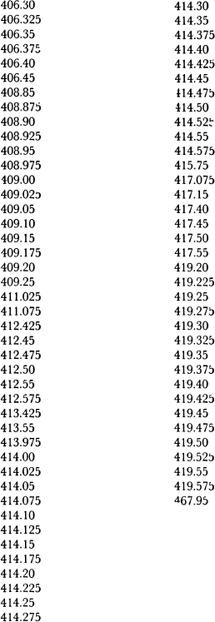

Not all U.S. government broadcasts can be identified as to agency. Conversations are cryptic; letters to the Federal Communications Commission and Commerce Department bring form replies. These frequencies (in megahertz) have been identified with the CIA:

163.81

165.01

165.11

165.385

408.60

Reported frequencies are:

Reported frequencies are:

Reported frequencies (in megahertz) are:

Room bugs are miniature radio stations. As such, anyone can tune them in. This rarely happens, though, because the range is limited and the frequency is known only to the person who placed the bug.

In practice, most bugs transmit by frequency modulation, on or near the standard FM broadcast band (88 to 108 MHz). There is a toy called Mr. Microphone that is, in effect, a bug shaped like a large hand-held microphone. The user speaks into the microphone, and others may hear his voice on their FM radios. Clandestine bugs work similarly but are more likely to transmit just off either end of the FM band—from 86 to 88 MHz (which infringes on a band allocated to television channels 5 and 6) or 108 to 110 MHz. In that way, the chance of accidental interception or of someone complaining to the Federal Communications Commission is less. The Watergate bug was to have transmitted at 110 MHz.

You can check for bugs using an FM radio. Turn the tuner to the extreme left side of the dial, as far as it will go, and turn the volume up. Although 88 MHz is the lowest frequency marked, most receivers have enough “overcoverage” to pick up 87 or 86 MHz. No FM station, are assigned below 88 MHz, so anything you may hear there is suspicious. Slowly move the dial to the right until you come to the first commercial FM station. Sweep over the FM band proper, and then check the overcoverage region above 108 MHz. Any bug you hear will be in your immediate neighborhood: Typical transmitters use a few milliwatts of power and have a range of a few hundred yards. If you suspect the bug is in a nearby room, have someone talk or play music while you scan.

A few bugs can be picked up only with special shortwave receivers. The frequencies from 48 to 50 MHz and 72 to 75 MHz are sometimes used. Several shortwave operators have reported conversations that seem to be from room bugs at 167.485 MHz—an FBI frequency.

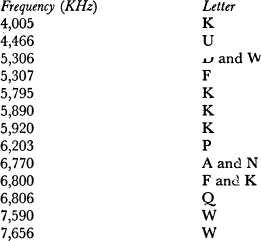

Dozens of low-power stations transmit only a letter of Morse code endlessly. No one, including government agencies and the International Telecommunications Union, admits to knowing where the signals are coming from, who is sending them, or why.

“K” (dash-dot-dash) is the most common letter. Letters are repeated every two to seven seconds, depending on the station. The stations never identify themselves. The frequency used for the broadcast shifts slowly with time, so this list is only an approximate guide:

These stations broadcast mostly during the night hours of North America. They are most often picked up in North America, Australia, and the Orient. But because of the easy propagation of shortwave signals, no one is sure where they are coming from.

An analysis in the Confidential Frequency List holds that the signals are coming from 25-to 100-watt unattended transmitters somewhere in the South Pacific. An alternate theory places the Morse code “beacons” in Cuba. It is known that there used to be a “W” station operating at 3,584 KHz, a frequency supposedly reserved for amateur use. When American amateurs protested to the Federal Communications Commission about the interference, the FCC complained to the Cuban government. The station disappeared shortly thereafter.

Actually, all of the beacons must be presumed illegal. Shortwave stations are supposed to be registered with the International Telecommunications Union; none of those listed above are. The purpose of the stations is as unclear as their location. A single letter conveys no information. There are legitimate navigational beacon stations, which broadcast their call letters. But such stations are registered and operate on fixed frequencies from known locations. Keeping location and frequency information secret would defeat their purpose.

Maybe, then, the letter beacons are navigational stations operated for the benefit of a select few. Some think they are operated by the Soviet Union, in Cuba, for some military purpose. Still, the globe is crosshatched with legitimate navigational beacons. It is hard to see what further navigational aid the Soviets could expect to derive from their own secret network of beacons.

It has also been suggested that the beacon stations are really teletype or other data-transmission stations and that the Morse code letters are just a way of keeping the channel clear between data transmissions. A few of the stations started transmitting some sort of data—audible as a characteristic high-speed typewriterlike sound—in 1980. There are other ways of keeping a data channel open, though. Most radioteletype stations transmit the signal for a “space” (as between words) or a similar device between transmissions. (The radioteletype code is different from Morse code.)

Finally, still others think the letter transmissions are themselves some sort of coded message. Granted, the letter can’t mean anything, but some wonder if the precise length of the interval between the letters means something. Or the frequency shifts may hold the message.

The number of Morse code letter stations seems to be increasing.

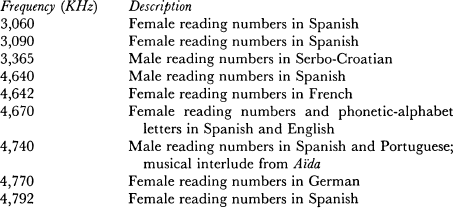

Well over a hundred “numbers” or “spy ‘ stations nave beer reported, all rather closely following a pattern. On the typical numbers station, the announcer is—or seems to be—a woman. No one knows who the woman is or where she is broadcasting from. She speaks in Spanish, German, or Korean. Save for a few words at the beginning and end of the transmission, the message consists of random numbers, announced in groups of five, four, or, rarely, three digits. As with the Morse code stations, the numbers stations are all on unauthorized frequencies. No government or organization owns up to the broadcasts; officially, at least, the FCC claims no knowledge of them.

Many of those who have listened to the broadcasts carefully are convinced that the woman is in fact a robot. The voice has a mechanical ring, sometimes with a click between each digit. It seems to be the same sort of device used by the telephone company to give the time or forwarding phone numbers.

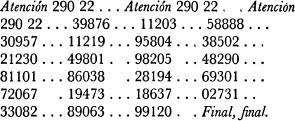

The exact format of the messages varies with the language and number of digits per group. With Spanish, five-digit groups, for instance, a typical message might be:

Broadcasts are during the night hours of North America and seem to start shortly after the hour. After the “final, final ” the transmission stops. It is claimed that a given transmission is repeated a few minutes later on a slightly different frequency.

There seems to be no escaping the conclusion that the messages are a numerical code. The second number after the “Atención”— 22 in the example—is the number of digit groups in the message. There doesn’t seem to be any demonstrable significance to the first number. Some suspect it is an identifying number for the sender or, more likely, the receiver.

The four-digit transmissions in Spanish are different. A three-digit number (perhaps that of the sender or receiver) is repeated several times, followed by the digits 1 through 0 (“uno, dos, tres, cuatro, cinco, seis, siete, ocho, nueve, cero”) and a string of Morse-code dashes. The word grupo is followed by the number of four-digit groups to come and repeated once—for example, “Grupo 22, grupo 22.” The message—groups of four Spanish-language numbers—follows. At the end the voice says, “Repito grupo 22,” and the message repeats. The station goes off the air after the repeat.

Any attempt to explain these stations is complicated by numbers broadcasts in other languages. There are also broadcasts in German (they start with ” Achtung” and terminate with “Ende”), Korean, and English. Occasional transmissions in Russian, French, Portuguese, and even Serbo-Croatian are reported. Sometimes a male (mechanical?) voice reads the numbers. The female robot voice doing English-language broadcasts is often described as having an Oriental or German accent. Typical of the uncer tainty surrounding numbers stations are the reported English-language messages prefaced with a female voice saying “Groups disinformation” and ending with “End of disinformation.” At least, it sounds like “disinformation.” Perhaps the voice machine has a bad rendering of “this information.”

Still other stations transmit messages consisting of letters from the phonetic alphabet (Alpha, Bravo, Charlie, etc.). Some spice their programs with music, which ranges from ethnic tunes to weird tones that may or may not conceal a message.

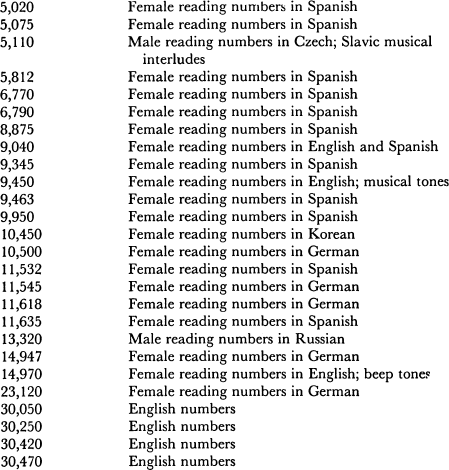

Reported frequencies for numbers and phonetic-alphabet stations include:

Whatever is going on, it’s a big operation. Harry L. Helms’ How to Tune the Secret Shortwave Spectrum has a list of sixty-two stations that includes only those with a female voice reading fivedigit numbers in Spanish. Much time and effort are going into the broadcasts. Some numbers stations transmit on upper sideband rather than amplitude modulation (upper sideband requires more elaborate and expensive equipment). Signals are usually strong. Because of ionospheric reflection, they can be picked up over most of the globe. This makes direction-finding difficult.

Two explanations are offered for the numbers stations. It is rumored that some of the stations are communications links in the drug traffic between the United States and Latin America. If so, Spanish is a logical language. The numerically coded messages could tell couriers where drops will be made, how much to expect, and other minutiae that would change from day to day. Weak support for this explanation comes from some amateur direction-finding, which seems to place many of the Spanish-language stations somewhere south of the United States.

But even those who subscribe to this explanation agree that other numbers stations, probably most of them worldwide, are engaged in espionage—governmental or organizational communication with agents in the field.

Which government? The Spanish-language stations are usually heard between 7:00 P.M. and 6:00 A.M. Eastern Standard Time. The night hours are best for clandestine broadcasting, as weak signals propagate farther. So the Spanish-language broadcasts are probably coming from a time zone not far removed from Eastern Standard Time. (The EST zone includes the central Caribbean, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru.)

On the basis of broadcast times and signal strengths, it can similarly be postulated that the German-language stations are coming from Europe or maybe Africa, and the Korean-language stations are coming from the Orient—reasonably enough.

As far as the Spanish-language stations are concerned, suspicion points to Cuba. In 1975 U.S. listeners reported muffled Radio Havana broadcasts in the background of some of the Spanish-language stations. A station at 9,920 KHz is said to have used the same theme music as Radio Havana.

But then there are American ham radio operators who swear that the Spanish-language stations must be in the United States. How to Tune the Secret Shortwave Spectrum tells of listeners in Ohio who reported four-digit-numbers stations coming in stronger than anything else on the dial except a 50-kilowatt broadcast-band station a few miles distant. Similar reports come from the Washington, D.C., area.

Probably the simplest of all the many possible explanations is that the Spanish-language stations are operated by Cuba for the benefit of Cuban agents in the United States. The Radio Havana broadcasts in the background would have been a mistake. The engineer was listening to Radio Havana and forgot the mike was on, or maybe Radio Havana and some of the numbers stations share facilities and the signals got mixed. The local-quality broadcasts heard in the United States could be Cuban agents reporting backto Havana. Each agent would have to have his own mechanical voice setup.

The actual explanation may not be the simplest, though. According to Helms, some shortwave listeners believe that the four-and five-digit Spanish-language broadcasts are entirely different operations. The four-digit transmissions, at least some of which seem to originate in the United States, may be the work of the U.S. government. Only the five-digit transmissions may come from Latin America—and may be associated with local governments or U.S. foreign agents. Harry L. Helms speculates that the United States may have faked the Radio Havana background just to divert suspicion from an American espionage operation.

Any glib explanation of the numbers stations is furthei hallenged by another incident Helms cites. An unnamed listener was receiving a five-digit-numbers broadcast in a female voice in Spanish. At the end of the transmission, the station (accidentally?) stayed on the air, and faint female voices were heard reading numbers in English and German. If the report is accurate, then the numbers stations could be the work of one worldwide operation. Choice of languages could be arbitrary. Whatever his or her native tongue, an agent need only learn ten words of, say, Korean in order to receive a numerical code in Korean.

No one willing to talk about it has broken the code or codes used for the transmissions. If the operation or operations are sophisticated enough, it may be pointless even to try. A random four-or five-digit number added to each number group before transmission will scramble the code. The numbers must be agreed upon by sender and receiver beforehand. If a different number is used for each number block and if they are not repeated, it is mathematically impossible for outsiders to crack the code.

There are still other inexplicable radio transmissions.

At 3,820 KHz there is a four-note electronic tune. The station never identifies itself; no one knows where the signal is coming from or why.

At 12,700 KHz there is a plaintive, twenty-one-note, flutelike melody.

At 15,507 KHz there are beeps.

The “Russian woodpecker” is a mysterious noise heard on frequencies ranging from 3,261 to 17,540 KHz. It is variously described as like a woodpecker or buzz saw. It was first heard in late 1976 or early 1977, seems to be coming from the Soviet Union, and is so powerful that it drowns out all other signals on its band. The usual hypothesis is that it is an experimental Soviet over-the-horizon radar system. Similarly, some think that 388.0 MHz—a frequency between VHF and UHF television carrier frequencies—is a resonant frequency of the human body being used in secret “death ray” experiments.

The most secret of transmissions are not even recognizable as transmissions. Without Cloak or Dagger, a 1974 book by former CIA agent Miles Copeland, tells of “screech” transmissions. These are tape-recorded messages speeded up or scrambled in such a way that they sound like radio interference. Only the intended recipient, with a variable-speed tape recorder or descrambler, can recover the messages.

More subtle yet is a device called the SC/16, manufactured by Transcript/International of Lincoln, Nebraska. The SC/16 is a “frequency-hopping” transmitter and receiver. Two synchronized units broadcast and receive at a frequency that changes every twelfth second. As many as twenty-four different frequencies are used, all between 145 and 166 MHz.

Any outsider tuning into this range would hear, at most, one-twelfth-second bursts of speech. The bursts are too fleeting to be recognized as speech; they sound like static