Figure 3.1. Gustave Courbet, Tableau of Human Figures: A History of a Funeral at Ornans or A Burial at Ornans, 1849–1850

Painting is the most beautiful of all arts. In it, all sensations are condensed; contemplating it, everyone can create a story at the will of his imagination and—with a single glance—have his soul invaded by the most profound recollections; no effort of memory, everything is summed up in one instant.

Paul Gauguin1

The imagination of Delacroix! This has never been afraid to climb the difficult heights of religion; the sky belongs to him, so does hell, and war. . . . Here is the true painter-poet! One of the few elect whose spirit extends to comprehend religion. . . . All the pain of the Passion impassions him; all the splendor of the Church illumines him.

Charles Baudelaire2

When Rookmaaker launched his description of the steps of modern art in France, he began with the challenges posed by the Enlightenment—the challenges not only to faith in God but to how we can know the world. This starting point finds support in events surrounding the French Revolution (1789), which, as is well known, set in motion a deliberate process of dechristianization during the 1790s in France. Christian worship was to be replaced by a cult of reason.3 Moreover, the subsequent separation of church and state was based not on mutual respect (as in the United States) but on a mutual hostility. This separation and the accompanying antagonism toward Christianity certainly had its influence on the rise of modern art.

But alongside this antireligious and anticlerical process there were other currents at work that vigorously disputed the secularism of the Revolution; indeed, the romantic movement that was to deeply mark nineteenth-century French art gathered its support and energy in part by opposing the secular rationalism of the Enlightenment. By 1815, accompanying the romantic reassertion of feeling and spirituality were signs of religious awakenings in many places in Europe, including France. In ways parallel to Schleiermacher in Germany (see chapter four), François-René de Chateaubriand (1768–1848) had introduced, with the publication of his Génie du christianisme (The Genius of Christianity, 1802), a new apologetic for Christianity that was consistent with the affective impulses of romanticism. As in Germany, the French purveyors of this new apologetic were more often artists and novelists than theologians. Maurice Denis (1870–1943), an artist who did much to recover sacred art in France, begins the modern chapter of his Histoire de l’art religieux by praising three nineteenth-century artists inspired by this revival: Pierre-Paul Prud’hon (1758–1823), who painted an influential crucifixion in 1823, copies of which were widely circulated; Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875), who read from Thomas à Kempis’s The Imitation of Christ each day and approached nature with humility; and Victor Hugo (1802–1885), who was greatly influenced by Chateaubriand. Denis wondered how the nineteenth century, which began so spiritually alive, could succumb to the stagnation of academicism.4

Working in the middle of the century, Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) represents an example of this influence at one remove. When Courbet showed his large (10 × 22 ft.) painting Tableau of Human Figures: A History of a Funeral at Ornans, known popularly as A Burial at Ornans (1849–1850), in the Salon of 1851, it was clear to everyone in Paris that a blow had been struck against the traditions of painting. (See fig. 3.1.) But the exact nature of the challenge—or better the various challenges—was not at all clear. For, as T. J. Clark points out, the picture represents multiple tensions—artistic, political, social and even religious.5

The picture provides an offhand glimpse of a rural burial. In a forlorn landscape, a group of mourners gathers before an open grave. There appears to be no visual focus—distracted and grieving peasants on the right are balanced by a (tellingly off-center) group of clergy and acolytes on the left carrying their liturgical implements: holy water, prayer book and crucifix. In typical fashion the women mourners are separated from the men. A man on the right gestures toward the open grave barely visible below while a priest to the left fumbles with his prayer book as he tries to gain the attention of a distracted crowd. All of this seems to resist a grand-scale interpretation to match the grand size of the canvas; indeed, nothing draws the viewer’s attention for long. And as Clark points out, “There is no exchange of gaze or glance, no reciprocity between these figures.” Courbet “deliberately avoids emotional organization” such that there is no dramatic moment, no affectation, no revelatory moment.6

Figure 3.1. Gustave Courbet, Tableau of Human Figures: A History of a Funeral at Ornans or A Burial at Ornans, 1849–1850

Though nothing in the picture shocks the modern viewer, something about it is vaguely unsettling. Though Courbet was famously anticlerical, the picture is free of irony. In fact, Hélène Toussaint has pronounced it “full of religious feeling.”7 Though it operates on the scale of Jacques-Louis David’s massive Coronation of Napoleon (1805–1807), and though the full title seems to place it in the grand tradition as the History of a Funeral at Ornans, the anonymous funeral is clearly not intended to portray any person or event of significance. At the same time, even though it is a rural scene, Burial did not fit the peasant genre championed by Millet’s The Sower (1850), which was shown in the same Salon. Indeed, Courbet seems to have gone out of his way to make it unadorned, banal, inelegant—following the canons of popular prints more than those of the academy. What bothered contemporary viewers was precisely its quotidian immediacy: “It was precisely its lack of open, declared significance which offended most of all.”8 It lacked the uplifting charm, idealism and beauty that attended the usual academic painting. But more than this, it boldly refused any clear narrative or iconographic meaning.9 Perhaps this is why Rookmaaker argued that Courbet took the critical step in the nineteenth-century tendency to reject subject matter: he had come to suppose that all previous principles and themes were empty and meaningless, and thus Courbet resolved to paint only what he could see.10 But with respect to religious influence and content, there is more to be said. To fully understand Courbet’s role, and its subsequent influence, one needs to pay careful attention to, among other things, the religious context of his work.

The renewal of faith that we described at the beginning of this chapter was not always compatible with the institutional church, even though its religious devotion issued in a strong commitment to social and political justice. In many ways it represented an attempt to recover a pristine form of Christianity, to return to the religion of Jesus. The politician and political theorist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809–1865) urged workers to “worship God without priests, work without masters, and trade without usury.” This call, Clark thinks, was influential on Courbet, who rode on its fervor, if not its substance.11 Hélène Toussaint in fact believes that Burial at Ornans reflects the religious commitments that lay behind the 1848 revolution.12 Proudhon himself was a follower of Claude Henri de Saint-Simon (1760–1825), who published his influential book on the New Christianity in 1825. There Saint-Simon focused on the spiritual aspects of society as the most important, and called on artists (“men of imagination”) to recover the way of Jesus and lead the way to a new period of social and political harmony.13 All of this was critical to Courbet’s program. Courbet and Proudhon were close friends, and Courbet’s program of social realism grew from Proudhon’s ideas, which in turn were rooted in Saint-Simon’s notion of a new Christianity. Proudhon joined those defending Courbet’s Burial, denying that it could be sacrilegious: “Of all the most serious events in life, the one which least lends itself to mockery is death, the last event of all.”14 The realism and social concerns represented by Courbet would have been impossible apart from this larger religious context. And as we will argue, these commitments also provided an arena for new forms of religious art to appear.

These influences also created a favorable climate for artists who were drawn to religious themes. One who represented this openness, perhaps surprisingly, was Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), who deserves a brief treatment here. Recent study has underlined the influence on Delacroix of the religious renewal we have sketched.15 Theological reflection in Germany and a revived Thomism in France combined with the emerging influence of romanticism to create a socially progressive Catholicism represented by Chateaubriand and Hugues-Felicité Robert de Lamennais. This environment encouraged painters to focus more on Jesus’ humanity and his life than on Catholic doctrine or creed. The undeniable influence of the French Revolution on this period has tended to obscure the continuing presence and seasoning of what we might call the Catholic imagination. Especially in rural France, where so many artists had their roots, and—as we will see in the case of Gauguin—found their inspiration, people retained a deep-seated sense of spiritual presence behind what the eye can see.

The work of Pierre-Paul Prud’hon reflected these influences, which in turn had a large impact on Delacroix, who said of him: “[Prud’hon] always spoke to the eyes through the soul.” He was deeply moved upon seeing a copy of Prud’hon’s Christ on the Cross (1822), probably during attendance at Mass. Afterward he recorded in his journal, “The emotional part seemed to rise up from the picture and to reach me on the wings of the music.”16 Delacroix’s choice of subjects—Jacob Wrestling with an Angel (1854–1861), Agony in the Garden (c. 1850–1851) and Christ on the Sea of Galilee (c. 1853–1854)—reflects a combined fascination with the forces of nature and the power of religion.17 The space and liturgy of churches especially stimulated his creativity: “The music, the bishop, everything is done to move one.” He was fascinated by the transcendence and beauty of sacred spaces, and he believed the inner presence of God “makes us admire the beautiful . . . and creates the inspiration of men of genius.”18 Though his religious paintings make up only about 10 percent of his output, they represent some of his most important work—especially in the last decades of his life. In Christ on the Sea of Galilee (1854), for example, Christ is endowed with a veil of light, sleeping peacefully amidst the fury of the disciples’ struggles with sails and rigging. In this painting (fig. 3.2), Delacroix employs his familiar palette and tumultuous style in the service of this familiar biblical story.19 In the turmoil created by the diagonal thrusts of the picture the eye is constantly brought back to the off-center figure of the sleeping Christ, as though to assure the viewer that amidst chaos divine peace can be found.

Figure 3.2. Eugène Delacroix, Christ on the Sea of Galilee, 1854

Still, if Delacroix shows the attraction religion had for artists of his generation, it would be wrong to call him a religious artist. Even Polistena admits that “Delacroix did not record an explicit yearning for the God of Christianity,” and he was never formally received into the church.20 Rather, his significance lies in proposing new possibilities for religious art, in a style that was more congenial to romantic sensitivities. Note that the influence of religion for Delacroix emphatically lay not in the doctrines but in the practices that it encouraged and the aura this evoked. This testimony from his journal is typical: “I was greatly struck by the Mass on the Day of the Dead, by all that religion offers to the imagination, and at the same time how much it addresses itself to man’s deepest consciousness.”21 While working on his murals at the Church of Saint-Sulpice in Paris, he especially enjoyed working on Sundays: “I have profited well from the time I spend in church, not to mention the music they make there, beside which everything else sounds thin. . . . I work twice as hard on the days the masses are sung.”22 Whether or not Delacroix deeply believed that the liturgy communicated God’s presence, he sensed the significance of these practices as openings to the transcendent. His awareness of the sacramental depth of things represented a constant influence in Catholic France, and this would again become important later in the century.

The decade of the 1850s, meanwhile, marked a turning point in France. From this point on public response to traditional religious subjects weakened dramatically. Nikolaus Pevsner in his review of the period notes that Delacroix was the last painter until the 1890s who could paint religious subjects. “The mid-nineteenth century was not religious and not enthusiastic,” he notes. “It was too realistic for that.”23 Courbet’s pride in being “without ideals and without religion” reflects this new secular spirit. (The Catholic Church for its part made a radical turn against modern developments in the 1850s, and strict Roman control won over the revitalized Gallican Church.) But it would be a mistake to believe this turn to realism was incompatible with religious expression. Indeed, we have argued that Courbet’s innovations rested, in part at least, on previous religious influences. And even if his (subsequent) refusal of faith is taken at face value, the fact remains that for most modern artists Courbet’s realism was a liberation that opened the way to new possibilities of expression, even religious expression. We might take the statement of Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger as typical. In their 1912 book on cubism they paid tribute to Courbet, claiming that “to estimate the significance of Cubism we must go back to Gustave Courbet,” who “magnificently terminated a secular idealism . . . [and] did not waste himself in servile repetition: he inaugurated a realistic impulse which runs through all modern efforts.”24 Nevertheless, while they admired this realistic impulse, they believed Courbet did not go far enough: “he remained the slave of the worst visual conventions,” not understanding that in order to discover a deeper truth one must be willing “to sacrifice a thousand apparent truths.”25 For them Courbet was “like one who observes the ocean for the first time, and who, diverted by the movements of the waves, has no thought of the depths.”26 That these comments were made by Gleizes is significant: he later became a devout Catholic and was one of the most important exponents of the use of abstract forms to convey religious feeling, which was his way of sacrificing appearance for something deeper.

But what did Courbet believe painting could do? He must have felt that his 1861 statement about painting was consistent with his political commitments: “Painting is an essentially concrete art and can only consist in the representation of things that really exist. An abstract object, invisible, does not belong to the domain of painting. The imagination in art consists in finding the most complete expression of an existing thing.”27 On the one hand, this influential pronouncement reflects developments in Europe during the previous century: the growing empiricism attendant on the scientific revolution, the focus on common people in their natural contexts that Rousseau encouraged and the growing opposition to entrenched authority that resulted from the French Revolution. These had already begun to influence culture in numerous ways. Burial at Ornans surely reminded many viewers of the popular prints that had become common in newspapers of those days. On the other hand, a turn toward the observation of the surrounding world, with its social and cultural crises, could just as easily reflect deep religious convictions as occlude them, even if that is not what Courbet intended. This is clear from the portrayal of landscape in the United States during this same period, which we will describe in chapter six.

It is common for art historians to see impressionism as a natural development of Courbet’s focus on what can be seen, and this is partially true. But if Courbet (and his contemporary Édouard Manet) sought, at least in part, to pique the contemporary bourgeois conscience, clearly this was not the intention of the impressionists. These followers of Courbet and of Manet turned their attention to the ordinary by focusing strictly on what can be seen with the eyes. Beyond this it is difficult to propose any unifying theory. They were an even more disparate lot than the symbolists who followed them—held together, as John Rewald has pointed out, more by the independent nature of their salons than by any common artistic program. But they are associated in most peoples’ minds with Claude Monet, who sought to portray the immediate impressions of nature, however fugitive its effects.

The popularity of impressionist paintings, especially among American audiences drawn to their bright airy quality, could not be more at odds with the critical views of subsequent critics and artists. Indeed, the short-lived character of the movement was due in large part to the ephemeral nature of the subject matter—artists immediately felt the need to move beyond this to something more substantial, something that carried symbolic meaning. As a contemporaneous painter Camille Mauclair writes later of the impressionists’ work, “The eye and the hand! superb, and it was enough: but nothing else.”28 In 1891 critic G.-A. Aurier, the promoter of Gauguin, had complained that the impressionists only conveyed form and color, an imitation of the material surface. The truth of things lay much deeper, he insisted.29 Gleizes and Metzinger offered a similar criticism: “The art of the Impressionists involves an absurdity: by diversity of color it seeks to create life, and it promotes a feeble and ineffectual quality of drawing. The dress sparkles in a marvelous play of colors; but the figure disappears, is atrophied. Here even more than in Courbet, the retina predominates over the brain.”30

Interestingly, these complaints sound much like those made by theologians commenting on the period. Colin Gunton argues that artistic movements of this time reflected a loss of substance: “G. K. Chesterton is reported to have said of the paintings of the Impressionists that the world in them appears to have no backbone, and some analyses of late modernity appear to confirm the judgment that a loss of substantiality is at the heart of the matter.”31 Gunton goes on to quote philosopher Robert Pippin, arguing that Manet’s choice of subject matter involves “a denial of the ‘dependence’ of the intelligibility of objects or persons or moments on the universal categories or descriptions of science or philosophy or even language as originally understood.”32 Rookmaaker’s judgment of the decisive step taken by Monet is even more strongly stated. He argued that Monet’s paintings claim that “there is no reality. Only the sensations are real.”33

But even if this were the case, there is a problem with making impressionism a precursor of twentieth-century modernist (and postmodernist) troubles. Whatever the weaknesses of the impressionist program, it cannot simply be a step in the direction of later cultural evils, as Rookmaaker and Gunton imply, precisely because the following generation of artists departed from impressionism at exactly this point: they rejected the notion that reality was all surface and that particulars exist in no intrinsic relationship to each other. The moves made by Cézanne and Gauguin in the 1880s and 1890s, which were to have the most significant influence on twentieth-century art, were precisely those that diverged most dramatically from Monet—in the search for a deeper structure of things in the case of Cézanne and for the mystical depths of a spiritual reality in the case of Gauguin. Since the full extent of Cézanne’s influence became apparent only later, we postpone that discussion and turn first to Gauguin.

Gauguin’s Vision After the Sermon: Jacob Wrestling with the Angel (plate 1) was finished in Pont-Aven by late September 1888 and represents a convergence of events that would transform not only Gauguin’s work but the course of modern art. Gauguin’s own title—Vision of the Sermon (vision du sermon)—more closely reflects his intention to reflect an interior vision that abstracts from nature. A group of Breton women stand in the foreground praying immediately following a sermon (the priest at the far right is a self-portrait of the artist). An abnormally curved tree—which Gauguin specifically identified as an apple tree34—arches from the lower right corner of the composition to the upper left, creating a visual division between the foreground and the background. The pious congregants all have their heads lowered in prayer—everyone except for a single female figure just left of center: she raises her head and looks across the diagonal tree where she sees a vision of Jacob wrestling with an angel (cf. Gen 32:24-32). The earth beneath these biblical wrestlers is a blazing vermillion red, which also extends beneath the feet of the churchgoers. Through his use of high-key color and strong composition he sought to convey the feelings aroused by the events portrayed—a method that came to be called “symbolist.”35 Thus the natural world of the pious women and the supernatural world of the vision are portrayed together in a single space that appears simultaneously unified and bifurcated.

Plate 1. Paul Gaugin, Vision After the Sermon: Jacob Wrestling with the Angel, 1888

This ambiguity raises the central question of the painting: are we to regard this vision with belief or incredulity? Is this community receiving revelatory insight into the biblical text, or is this only an illusory projection of the onlookers’ piety? Gauguin described this painting as having “a superstitious simplicity in the figures,” and it is precisely this superstition that he calls into question: “For me, the landscape and the wrestling exist only in the imagination of the people at prayer after the sermon; that’s why there’s a contrast between the real people and the wrestling in its landscape, [which is] not real and out of proportion.”36 On this basis, Judy Sund argues that “the religious fervor of the artist’s Breton neighbors is the real subject of The Vision. . . . The text from Genesis is peripheral to both narrative and image, and the artist’s stance is that of a curious skeptic who is emotionally distanced from what he observes. . . . The Vision presents religious experience through the eyes of a dubious outsider.”37

What led Gauguin, the curious skeptic, to such a striking portrayal of religious feeling? When in 1886 he fled the high prices (and summer heat) of Paris for Pont-Aven in Brittany, Gauguin little expected that the simple peasants of the area would influence him as they did. Brittany, like other parts of France, was in the midst of a religious revival of an apparitional Catholicism, and the arresting subject of Vision suggests that the religious context of Pont-Aven had stirred religious feelings in Gauguin. The revival at Pont-Aven included the recovery of a variety of medieval mystical practices and a flowering of devotional cults, especially the Pont-Aven Pardon, a two-day penitential celebration during the fall equinox. Gauguin found these so moving that he began to wear traditional clothes and attend the local parish church.38

Debora Silverman has argued that these experiences touched Gauguin especially as a lapsed Catholic because they resonated with his education in the seminary in Orleans, where he had trained for the priesthood. There he had been taught an idealist antinaturalism that focused on inward vision and imagination. Though he had subsequently rejected Christianity formally, Silverman thinks this rejection “co-existed with a mentality indelibly stamped by the theological frameworks and religious values that formed him.”39 Clearly he was recalling this instruction when he wrote in a 1888 letter to a critic: “Art is an abstraction; derive this abstraction from nature while dreaming before it. . . . This is the only way of rising toward God—doing as our Divine Master does, create.”40

The interest in religious things and the increasing religious references in his letters during this year had another cause as well. In 1888 Gauguin had just returned to Pont-Aven from a trip to the Caribbean island of Martinique, where a number of artists had gathered to escape the distractions of Paris. Though his trip to the tropical Martinique had enlivened his palette, Gauguin was still working in the impressionist mode of his teacher, Camille Pissarro. But he told his friends he was seeking a “synthesis” between his focus on colors and something deeper.41

When the young painter Émile Bernard (1868–1941) arrived in Pont-Aven in August 1888, he immediately looked up Gauguin, whom he had heard about from Vincent van Gogh, and they soon became close friends. Van Gogh had come to Pont-Aven in February, and after Bernard’s arrival their animated conversations undoubtedly touched on religious as well as artistic subjects. Though much younger (Bernard was barely twenty, Gauguin an aging forty), Bernard was an articulate and convincing champion for some of the newer ideas he brought from Paris. He surely contributed to Gauguin’s attraction to the intellectual and systematic construction of space and the Japanese cloissoné style (areas of solid colors divided by sharp outlines). These proved influential on Gauguin, who (as the more talented artist) developed them beyond what Bernard had been able to do.42 The synthesis that Bernard and Gauguin sought was between their experience of nature and the colors and forms of their painting. According to Caroline Boyle-Turner, their aim was to “adapt what they saw in nature to their own emotional experience and graphic sensibilities.”43 Such was the ability of young Bernard to express his views that he soon won over Gauguin, and, whatever differences they would later have, at the time they seemed to be in complete agreement.

Beyond his stylistic influence, Bernard also sparked the spiritual sensitivities of the older painter. As already noted, Gauguin was struck by the mystical depth of Brittany’s Catholicism and by the starched collars and embroidered vests the faithful wore to church on Sunday. And Bernard was enlivened by the recent recovery of his own Catholic faith. Urged on by Bernard, they attended services together and became friends with the priest. One of their number, the Dutch painter Jan Verkade, converted to Catholicism as a result of these experiences and later became a monk. In fact, Denys Sutton suggests, “Bernard’s growing devotion to Catholicism possibly helped Gauguin paint [Vision].”44 John Rewald characterized the relationship this way: “So great was the younger painter’s ascendancy over [Gauguin] that even Bernard’s religious fervor was reflected in Gauguin’s letters.”45 Taking account of Silverman’s claim for the continuing influence of Gauguin’s religious instruction, it is not a stretch to see that Bernard’s impact alongside the medieval faith of Brittany’s peasants may have awakened Gauguin’s sensitivities to the spiritual depth of what he observed. Moreover, he must have been impressed with the role of liturgical practices in appropriating those depths. While it may be difficult to specify precisely what this meant for his artistic practice, it is surely part of the stimulus that led to the development of his symbolism.

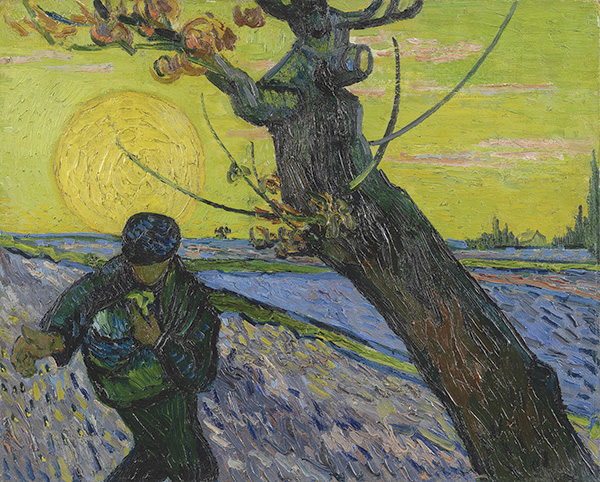

Van Gogh had arrived in Paris from Holland in 1886 (having only started painting in 1880), and by 1887 he and Gauguin had begun exchanging letters and drawings. Debora Silverman notes that both artists were working within the symbolist agenda but were moving in opposite directions: “Gauguin by dematerializing nature in a flight to metaphysical mystery; van Gogh by naturalizing divinity, in the service of what he called a ‘perfection’ that ‘renders the infinite tangible to us.’”46 Van Gogh’s religious background, in its particularly Protestant form,47 clearly motivated his vehement search for transcendence in and through the empirical world—a search that will be more fully explored in the next chapter. “With van Gogh,” Robert Rosenblum notes, “we feel anew the kind of passionate search for religious truths in the world of empirical observation.”48 In 1888 van Gogh, stimulated by his exchanges with Gauguin, painted The Sower, a work of similar size to Vision, reflecting his divergent religious trajectory.

Van Gogh painted multiple versions of The Sower in the latter half of 1888, but it is the third version (plate 2), painted in November of that year,49 that is of particular interest here: he seems to have intended it as a direct riposte to Gauguin’s Vision. Van Gogh borrows Gauguin’s compositional structure, dividing the image diagonally in half with the same kind of curved tree growing from the lower-right corner of the foreground. This compositional quotation sets the two paintings into a dialectical relationship (all dissimilarities suddenly becoming loaded with significance), and it provides the means by which van Gogh asserts a pointedly different visual theology. According to Judy Sund, “Van Gogh himself probably measured this latest Sower against The Vision, and very likely conceived it as a subtle rebuttal to Gauguin’s approach and attitude. The tree probably should be seen as simply the most visible manifestation of the web of ideas that connects the two pictures.”50

Plate 2. Vincent van Gogh, The Sower, 1888

If the tree “connects” these two works, van Gogh’s construction of the space surrounding this tree—particularly his management of the contrasts that the tree sets up between left and right, foreground and background—creates sharp intentional contrasts with Gauguin’s religious Vision. Gauguin’s tree serves as a means to distinguish between the tangible, factual “here” of the congregants and the intangible, visionary “elsewhere” of the biblical subject matter. Van Gogh accepts this division but radically revises its logic: he places the biblical figure—the messianic Sower—in the foreground on the left side of the tree, concretely on our side. And in fact the sower moves toward us as though the field on which we stand is also the object of his labor. The revelatory vision of God confronting us happens in the foreground rather than in the distance and in the guise of a working peasant rather than an angel—van Gogh is thinking through the logic of incarnation here. He retains the “elsewhere” of the space beyond the tree, but he renders the distance as eschatological rather than only metaphysical or imaginative: in the far distance appears the house of the Farmer to whom the harvested wheat will eventually be brought in.

Like Gauguin’s painting, this too is an image of wrestling with God; but (as is consistent with his Protestantism) van Gogh has relocated the arena for the struggle into the heart. This painting is, after all, derived from the biblical parable of the sower (Mt 13; Mk 4; Lk 8), which is actually a parable about the soils over which the sower toils: the focus of Jesus’ story is the quality of people’s hearts (soils) as they hear him, some of which will sustain growth while others will not. The implication is that if one is going to wrestle with the person of Jesus, one must also tend to the quality of one’s heart. In reconstituting Gauguin’s compositional structure around this parable in this way, van Gogh is presenting his own sense of what it means to wrestle with God—one that is alternative to Gauguin’s take on the matter. Notice the contrast: Gauguin sought to use images in the fashion of Catholic mysteries, which refer to a transcendent spiritual world; van Gogh pursued a spirituality incarnated in, with and under his twisting forms and lively palette. Sund summarizes:

Van Gogh—for all his unorthodoxy—was a firm believer. . . . While The Vision presents religious experience through the eyes of a dubious outsider, The Sower suggests that for the true believer, religious impulse is not so much the stuff of visions as a part of daily life, as Christ reveals himself by less sensational, much more down-to-earth means.51

Though he visited Gauguin in Brittany, van Gogh was drawn more to the Provençal landscape at Arles (in the South of France), which reminded him of his native Holland.52 The motif of the sower was no doubt inspired by Millet’s famous work, but it is clearly indebted to the technique of building up subjects by individual brushstrokes characteristic of the early Gauguin (before the impact of Bernard) and his teacher, Pissarro. It also anticipates the rough textures characteristic of van Gogh’s subsequent work. The rich colors were intended to add their own radiance to the scene. Van Gogh had written to his brother Theo in September 1888: “I’d like to paint men or women with that indefinable something [je ne sais quoi] of the eternal, of which the halo used to be the symbol, and which we try to achieve through the radiance itself, through the vibrancy of our colorations.”53 Van Gogh presents the world of his Sower as not only radiant with color; he also retains the symbolic weight of the halo in the massive sun that sets on the horizon directly behind the sower’s head—all of which, one must presume, was aimed at identifying the sower’s labor with that “something of the eternal.”

Van Gogh’s painting then was also symbolist in that he sought by means of color and composition to portray the emotion and meaning that his subjects stimulated in him. But the forms were symbols not of dreamlike visions as in Gauguin—van Gogh pointedly avoided representing the popular Catholicism around him—but of his longing for an ineffable “something on high” (quelque chose là-haut) that enlivens all things with its presence and meaning. But as Silverman puts it, he believed this something on high in fact reveals itself as “emanation from below, embodied in a generic labor figure framed by a blazing sun, luminescent with the color once reserved for Christ’s nimbus.”54

Silverman argues that these pictorial choices, as with Gauguin, grew naturally from van Gogh’s unique religious background. This is revealed even in his choice of peasant workers as a favorite topic, reflecting his Dutch Reformed conviction that useful and productive manual work could be a means of grace. Indeed, he likened his own artistic work to weavers at the loom or laborers in the field: “I keep my hand to the plow, and cut my furrow steadily,” he reported to Theo. “I keep looking more or less like a peasant,” except that “peasants are of more use in the world.”55

This also reflects the influence of the Groningen theologians, an evangelical group to which van Gogh’s family subscribed and which his father, a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church, had preached to his congregation for two decades.56 This movement stressed an inner surrender to Christ that manifested itself in a humble outward service to others in the name of Christ. These Dutch Christians treasured Thomas à Kempis’s Imitation of Christ and Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, which van Gogh had with him in Arles.

Little wonder that van Gogh was immediately attracted to the faith of Émile Bernard. Their extensive correspondence reveals a deeply shared faith. In June 1888 he told Bernard how happy he was that they both loved the Bible, even if they had ongoing doubts about it and even if it impacted their artistic practices differently. Despite the “despair” and “indignation” that van Gogh had come to feel toward some aspects of the Bible, he nevertheless clung to “the consolation it contains, like a kernel inside a hard husk, a bitter pulp—[which] is Christ.”57 For him, Christ was “an artist greater than all artists—disdaining marble and clay and paint—working in living flesh . . . [making] living men, immortals.”58 And as van Gogh saw it, the kind of artistic practice to be derived from this was one that was intensely alert to the realities of everyday “living flesh.” His submission to Christ was manifested in a commitment to the natural order rather than to representations of biblical subject matter.

In November 1889 van Gogh wrote to Bernard, taking issue with that painter’s “biblical paintings,” which he considered a “setback.” He agreed that “it is—no doubt—wise, right, to be moved by the Bible, but modern reality has such a hold over us,” such that devoting oneself to pictorially reconstructing ancient biblical narratives was a distraction from the more pressing theological work to be done. Rather, van Gogh believed that an artist’s religious striving should be more directly concerned with contemporary life, “always giving due weight to modern, possible sensations common to us all.”59 He urged Bernard to recognize that the spiritual themes he was wrestling with in his work might be better grounded in observation of the world around him: “In order to give an impression of anxiety, you can try to do it without heading straight for the historical garden of Gethsemane; in order to offer a consoling and gentle subject it isn’t necessary to depict the figures from the Sermon on the Mount.”60 Indeed, he advocated for a religious sensibility oriented toward concrete, lowly subjects: “My ambition is truly limited to a few clods of earth, some sprouting wheat. An olive grove. A cypress.” And such subjects were, for van Gogh, intensely spiritual: “I adore the true, the possible, were I ever capable of spiritual fervor; so I bow before that study, so powerful that it makes you tremble, by père Millet—peasants carrying to the farmhouse a calf born in the fields.”61 But, as he argued, this kind of spiritual perception necessitated a different frame of reference from the one Bernard was assuming: “It’s truly first and foremost a question of immersing oneself in reality again, with no plan made in advance, with no Parisian bias.”62 Here van Gogh mined a strong theme in the Reformed tradition that saw the created order as a reflection of God’s goodness—a theater for the glory of God, as John Calvin put it.

Despite their differences—van Gogh’s focus on nature differed markedly from Bernard’s popular images of faith—Bernard remained faithful to his friend Vincent. In fact he later arranged the first solo exhibition of his work. Douglas Lord claims that it is “to Émile Bernard more than to anyone else that the early recognition of van Gogh is due.”63 By the time he had written this letter to Bernard, van Gogh’s mental state was deteriorating; he had been hospitalized in Arles and later admitted himself to an asylum at Saint-Rémy. His brother Theo continued to faithfully support him, despite his obligations to a new wife, and he managed to show Vincent’s paintings in Paris (1889) and Brussels (1890), though nothing sold. Vincent, despairing that he was only a burden to Theo, shot himself in the chest on July 27, 1890, and with Theo at his side he died two days later.

The precise nature of Gauguin’s faith is harder to assess than that of van Gogh. Though he clearly was wrestling with deep religious questions, he did not formally embrace Bernard’s Catholic faith. For this reason scholars have been inclined to dismiss, or more often simply ignore, the influence of religion on his work. But our discussion has shown that the very different religious traditions represented by Gauguin and van Gogh played a significant role in their different approaches to symbolism, and even in the stylistic innovations to which they were drawn. Debora Silverman, in her study of these two artists, sought to show how “religious legacies provide a new point of entry with which to consider van Gogh and Gauguin’s collaboration.” But her claim is more ambitious than this; she wants to use these case studies as evidence for the larger “role of religiosity in generating form, structure and content of varied types of modernist expressive arts.”64

How might this claim be supported? The case of Gauguin is more complex than that of van Gogh in part because of his subsequent career and his two sojourns in Tahiti between 1891 and 1900, and even more by the variety of religious influences at play during this time. During his travels, Gauguin’s anticlerical views seemed to have hardened as he sought in Tahiti new kinds of mystical experience. He admitted in a letter to Paul Sérusier that his work there disturbed him and he was sure it would appall Parisian audiences as well: “What a religion, this old Oceanic religion! What a marvel! My brain is bursting with it and all the things it suggests to me will frighten everybody.”65 But this does not mean that he simply abandoned his own Catholic heritage. At one point he could echo Nietzsche in calling for the death of God—or at least the death of a “God-creator who is tangible”—while simultaneously claiming, however, that the “unfathomable mystery” to which the word God refers even now resides with the poets.66 Gauguin believed that deep links and “affinities” remained between Christianity and modern society, but these needed to be worked through more rigorously and reconciled into “a single, revitalized whole, richer and more fertile. But! But, outside of the Catholic Church, which is petrified in its hypocritical pharisaism of forms draining away the truly religious substance.”67

Though he maintained a deeply antagonistic attitude toward the “pharisaism” of the institutional church, he nevertheless retained a positive view of Christianity, as he did, for example, in his 1903 article on “Catholicism and the Modern Mind.”68 Echoing the call of reformers through the centuries, he lamented how the truth of Christ had been denatured by the Catholic Church.69 For the teachings of Christ lie at the basis of all human society, and we need to bring these together into a “new revitalized whole, richer and more fertile.”70 While he conceded that much in Scripture is unclear, some of the teachings are “clear enough for us to grasp their real meaning at first sight,” which he thought was especially true of what he called “the parable of the Last Supper.”71 Gauguin was haunted by the central Catholic ritual whereby the bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ, though he continued to believe that there is some real sense in which Christ’s meal invites us into “those perfections which will gradually assimilate us into divine nature”:

And calling himself the son of God, he says: “I am the living bread; if any man eat of this bread, he shall have life forever.” And to make his meaning perfectly clear, the Bible has the apostles say: “How can this man give us his flesh to eat?” which enables him to answer, “He that eateth my flesh . . . even he shall live by me,” and this clearly explains that we must take this to refer to the spirit [or Spirit]. When he partakes of the Last Supper with his disciples, he symbolizes the bread and the wine which, eaten and drunk together in a gathering of companions, form one flesh and one blood. . . . “Eat . . . drink . . . do this in remembrance of me.” These words mean, “I shall be in you and you in me.” Is not all of this outstandingly rational, intelligent?72

The problem, he goes on to argue, is that the church has lost sight of this simple reality and made it into a lifeless dogma. Perhaps his experience of the ritualized religion of Tahiti had caused him to reflect more deeply on the sacramental depths of a reality that was grounded in the Catholic view of God. One scholar has argued that Gauguin went to Tahiti seeking “a culture where art and life were interchangeable: where religious ritual, myth and mystery still had meaning.”73 If this is true, then it is likely that the motivation to seek such ritual experience was, in part at least, religious. And his reflections in this article show, even in this new context, how deeply ingrained Catholic practices continued to shape his artistic imagination. Especially notice how he sought to retrieve the central Eucharistic practice and its symbolic content, even if he eschewed the dogmatic teachings.

Maurice Denis, a younger member of the 1890 symbolist movement, later wrote that Gauguin allowed them to escape the dilemma of the real and the ideal posed by the neoclassical artist Jacques-Louis David. It was Gauguin, Denis notes, who saw painting as first and foremost a colored canvas, but in symbolist thought this idea was developed to mean that painterly media, especially color, could evoke religious feelings. Denis defined symbolism as “the art of translating and provoking states of the soul, by means of relations of colors and forms.”74 For Denis these states of the soul clearly had a spiritual dimension, and the symbolic power of art, for him, reflected the underlying reality of Catholic liturgy and the sacraments. As he later summarized these movements: “The liturgy, being based on the traditional rapport between the images of the sacred text and revealed truths, between the phenomena of nature and those of the interior life, brings a special light to artists, whose function is to translate the truths of faith into the language of poetry.”75

Gauguin’s writings and those of other artists of the period show that other religious influences were at work as well. A Western appropriation of Eastern philosophy called theosophy and various forms of the occult were becoming influential throughout western Europe during this period. During the 1880s many artists and writers were becoming disillusioned with the realism of Zola and the growing positivism. In 1884 J.-K. Huysmans broke with Zola and published À rebours (Against the Grain), which celebrated the symbolic connection between things and the poetry of Verlaine and Mallarmé. Of the latter, Huysmans wrote, “Perceiving the most remote analogies, he often designates an object or being by a word, giving at the same time, through an effect of similarity, the form, the fragrance, the color, the specific quality, the splendor.”76 Later, after converting to Catholicism, Huysmans became an important encouragement to the Catholic artistic revival.77

Perhaps the most influential expression of this spiritualist movement in France was Édouard Schuré’s book Les grands initiés, published in 1889.78 Schuré develops what he calls the ancient truth that has been secretly passed on from the time of ancient Egypt, essentially a gnostic vision of reality wherein the spiritual soul is seeking liberation from its material context. The book fit well with the reactionary mysticism that rejected the filth and decadence of a rapidly industrializing society, and it made the rounds among the artists in Paris and Brittany. Interestingly, after elaborate portraits of (among others) Rama, Krishna, Hermes, Moses and Plato, Schuré ends his book with a long and adulatory chapter on Jesus. There are three events in the life of Christ, he argues, that are essential for the life of the divine nature to be appropriated: the last supper, the trial and death, and the resurrection. But it is the first of these that is, for him, the symbolic and mystical culmination of all the teaching of Christ—as well as being the rejuvenation of ancient symbols of initiation such as grapes, bread, etc.79 By giving these symbols to his disciples, Schuré says, Jesus “enlarges them. For, by means of these, he extends the fraternity and initiation, formerly limited to some, to humanity at large. Christ introduces there the most profound mystery, the greatest power: that of his holy sacrifice.”80 This makes possible, he thinks, a chain of loving that unites all people and represents the spread of the social temple of Christ around the world.81 Schuré calls this the greatest religious revolution of all time, which captures and combines all the esoteric wisdom of previous eras. However, he insists that all this must be separated from the absurd claim that Jesus’ bodily resurrection is real, a doctrine that he believes came into the church only after Gnosticism had been suppressed.82

This version of Christian truth would not have earned the approval of the religious authorities of that time, but it did take a basic teaching of the symbolic nature of material reality—and the focal point of that symbolism in the central rite of Catholic Christianity (the participation in the body and blood of Christ)—and put it in terms that artists were able to apply to their understanding of form, color and structure. And for some the spiritual searching represented even by theosophy and the occult served as a way station on the way to Christian faith. Werner Haftmann reports that Paul Sérusier brought Schuré’s book to Pont-Aven, where it evidently played a role in Verkade’s conversion to Catholicism.83 What is often overlooked is the way that in France a sacramental sense of reality—that there is a depth to things that can be symbolically elicited—was indebted to the deeply ingrained traditions of the Catholic Church. However resistant artists may have been to the church as an institution, they often displayed the persistent influence of this sacramental imagination.

This was particularly true of Gauguin. As he says: “Painting is the most beautiful of all arts. In it, all sensations are condensed; contemplating it, everyone can create a story at the will of his imagination and—with a single glance—have his soul invaded by the most profound recollections; no effort of memory, everything is summed up in one instant. [It is] a complete art which gathers all the others and completes them. Like music, it acts on the soul through the intermediary of the senses: harmonious colors correspond to the harmonies of sounds.”84 Rather than impeding the development of sacred art, the symbolists believed that this imaginative alchemy of lines, colors and objects greatly expanded it, and this impulse became critical for the revival of religious art in the subsequent decades. Joseph Pichard says of Gauguin: “haunted by the sacred [he] reinvented a language for sacred art.”85 The significance of this period for the subsequent developments of modern art is widely recognized, of course. But this discovery of symbolic depth surely depended on the Catholic sacramental ideas that symbolists embraced, and it was this sacramental sensibility that prepared the way for a significant flowering of religious art in France and beyond.

In a way, the revolution launched by Courbet—that painting must function first and foremost as a flat canvas covered by forms and colors—remained unfinished until artists determined what this function meant. Impressionists made the play of light and colors their focus, but this proved unsatisfying to subsequent artists. Gauguin was the first to suggest that the form, supported by the structured use of “abstracted” color, was essentially a sign of something else, something deeper and more real. There were many factors that led him to take this step, but significant among these was surely the sacramental context of his Catholic culture and his own theological training, which was vividly displayed for him in the pious Bretons. And as Maurice Denis and Georges Rouault (among others) were to demonstrate, if the roots of these stylistic moves were partially religious, they could fruitfully be appropriated in the service of a new kind of sacred art. At the very least nothing about them was intrinsically secular.

Rookmaaker shares the assessment of many critics of this period, that the naturalism of impressionism prepared the way for twentieth-century developments. Rookmaaker in fact goes so far as to say of Gauguin and his circle that in their synthesis of human freedom and respect for the substance of nature, “their art was probably the fullest and richest the world had seen since the seventeenth century.”86 But he did not see any relation between this advance and the recovery of a religious view of the world. In fact he believed that these artists were wrestling with the Enlightenment motifs of form and freedom, from which they were unable to free themselves. They were struggling, he thinks, with “the primacy of the human personality (in his freedom) and that of the primary science motif (in its search for laws of nature).” No synthesis between these was possible, Rookmaaker claimed. The Catholic faith of Bernard meanwhile was “a pure Neoplatonism only slightly christianized,” confined within its own nature/grace dichotomy.87 But such an ideological reading of this period is mistaken on both historical and theological grounds. Historically the period is far too complex to be understood in terms of such a simplistic reading of the Enlightenment. Indeed, one can argue the contrary view: romantic and symbolist poets had introduced emotional and religious values that undermined the Enlightenment project, which they specifically rejected. And this suggests the theological error of Rookmaaker’s reading of this period. It is true that this recovery of spirituality, for many, was mixed with forms of esotericism and occult practices. Still, fundamental Christian values and liturgical practices, with ancient roots in medieval liturgical and mystical rituals, allowed many artists to understand the depth of nature and its symbolic potential. Seeds were being planted that later came to full flower in the Catholic revival in art and literature, to which we now turn.

Émile Bernard’s influence was not to be limited to his impact on Gauguin and van Gogh. Along with many others, he would be part of a religious revival that would have a deep and lasting impact on French culture. Bernard’s sojourn in Brittany had deepened his faith and his determination to support the church. He says of this time: “I became a Catholic ready to fight for the church. . . . I became intoxicated with incense, with organ music, prayers,” which he knew would isolate him more and more from his own period.88 Bernard’s views on the symbolism he sought and its religious grounds were articulated in a programmatic article he published in the Mercure de France in 1895. “If visible things are the face [la figure] of invisible things,” he writes, then it follows that the artist, “reflecting the divine and gifted with harmony, takes and transforms nature exercising his own supremacy, to make it express his unique and supernatural origin.”89 He deplores that art has lost sight of its religious origins and has been taken over by specialists. He argues that originally mysticism and art were joined, and the language of art was symbolic, so that theology, properly understood, is insatiable (avide) for painting.90 He was surely thinking of the simple piety of the Breton believers when he wrote, quoting the sixth-century mystic Pseudo-Dionysius, “The veil is only lifted for the sincere lovers of sanctity, [who] by the simplicity of their intelligence and the energy of their powers of contemplation, penetrate the simple, supernatural and supreme truth of these symbols.”91

The secularizing and anticlerical influence of the 1789 French Revolution had made deep inroads in nineteenth-century France, often making common cause with a growing faith in science and rationality. But this proved unsatisfying to artistic sensitivities. Toward the end of the century, artists and writers like Bernard began to look longingly toward their Christian past, much as their contemporaries, the Pre-Raphaelites, were doing in Britain. Bernard lamented that though the best art is religious art, in the past three hundred years nothing had captured the Christian ideal like the cathedrals had before that.92 Religious and mystical stirrings became common among artists, whether influenced by the Catholic tradition or by Eastern religions expressed in the new theosophical movements. These movements were welcomed by many artists as a means of escaping the confining materialism around them.

Maurice Denis, in his Histoire de l’art religieux, locates the rebirth of modern sacred art in Pont-Aven, where Paul Sérusier, Bernard and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes learned from Gauguin to return painting to the “purity and naiveté” of primitive poverty. Denis believed that it was Puvis, in particular, who had given the clearest expression of symbolism. He was able to “elucidate a confused emotion [existing like] a chicken in an egg . . . translating this with exactitude.”93

The journal Mercure de France was founded in 1890 specifically to promote these symbolist ideas. In an important article in 1891, G.-Albert Aurier identified Gauguin as the key to this movement.94 With an epigraph from Plato’s Republic, Aurier frames the movement as a progression beyond the “realist” impulse in art to the “idealist” (idéist). He alludes to the night when Emanuel Swedenborg claimed his interior eyes were opened to “see into the heavens in the world of ideas,” which fulfilled Plato’s goal of leaving the shadows for the light of day.95 The goal of the symbolist artist is then to select from multiple means, such that “the forms, and general and distinctive colors serve to write clearly the idealist [idéique] signification of the object”—and in this he thinks Gauguin has been the leader, the true “seer.”96 What mattered was that all hint of materialism had been banished from his work. Clearly here, as Rookmaaker observed, the recovered Catholic faith was mixed with Platonism and the new spirituality represented by Swedenborg. Bernard apparently was not worried, and he forged ahead with his program of renewal.

From these varied roots, in the early 1890s a group of artists gathered in the Saint-Germain quarter of Paris and began to consider a new kind of sacred art, one that might recover some of the glory of its Christian history. Such was the enthusiasm for the sacred, Maurice Denis argues, that they took for themselves the appellation Nabis (Hebrew for prophets). Critic Joseph Pichard similarly pointed out that during this time a few pioneers, painters of the soul, including Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon, had opened the way for development of a truly sacred art.97 These alone, Denis says, maintained the “rights of the soul in the plastic arts.”98

One of the leading voices in the movement was J.-K. Huysmans (1848–1907), who argued that “the real proof of Christianity is the art it has created, art which has never been surpassed.”99 Huysmans prepared the way with the publication of his novel À rebours (1884), to which we have referred. This recognition of the symbolic connection of things represented a clear break from the realism of Émile Zola and the impressionists, and marked a significant stage in Huysmans’s own pilgrimage, which was typical of others during this period. In 1890 he became deeply involved with the occult, an experience that he recorded in the novel Là-bas (1891).100 But in 1895 he published En route, which was a thinly disguised account of Huysmans’s own conversion to Catholicism.

During the 1890s Huysmans contributed to the discovery of Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon, who were little known at the time. Moreau, who later became the teacher of Henri Matisse, Edvard Munch and Georges Rouault, developed his intricate allegories to reflect what he called “imaginative reason.” Redon stressed the role of imagination and effaced, Huysmans believed, the border between reality and fantasy. Moreau, Redon and their contemporary Puvis de Chavannes opened the way, often by dream or hallucination, to another world and stressed the need for forms to take on symbolic meaning.

Figure 3.3. Gustave Moreau, Oedipus and the Sphinx, 1864

Moreau pointed his students to an interior vision. Later Rouault recalled Moreau’s confession:

I am asked: Do you believe in God? I believe only in God. In fact I do not believe in what I touch nor in what I see. I only believe in what I cannot see; solely in what I feel [sens]. My mind and my reason seem to me ephemeral and of a dubious reality. My inner consciousness [sentiment intérieur] alone appears eternal and unquestionably certain.101

A good example of his influence can be seen in Oedipus and the Sphinx (1864), a work displayed earlier in the Salons of 1864 and 1865, in both of which he won medals. (See fig. 3.3.) Though critics complained about his pedantic insistence on Renaissance imagery, and his annoying accumulation of detail, his handling of this theme was riveting for many viewers. The theme is explained in Édouard Schuré’s work as the human struggle to outwit the hierarchy of forces in nature. The two mythical figures are transfixed as they gaze at one another, each a kind of mirror image of the other.102 Moreau here employs mythical imagery as symbols, thereby suggesting a reality we cannot see rather than describing the one we see. This project set artists influenced by him on a quest to find pictorial means to evoke this unseen reality.

The decades around the turn of the twentieth century in France witnessed the full flowering of this Catholic revival, one much more profound and long lasting than a century earlier, in a culture that had grown tired of the secularism of the 1789 Revolution.103 Sparked by radical voices like J.-K. Huysmans and Ernest Hello, this movement featured highly visible conversions that led to a widespread recovery of Catholic faith among intellectuals. The major exponents in addition to Huysmans were Paul Claudel, Charles Péguy, George Bernanos, and Jacques and Raïssa Maritain, though this movement was later to influence François Mauriac and even the British author Graham Greene. In one way or another all of these had their roots in the symbolism we have described.104 The most important visual artist among these was Georges Rouault. Of these, Jacques Maritain (1882–1973), a close friend of Rouault and arguably dependent on Rouault for certain emphases of his aesthetics, proved to be the most prominent influence on artists of faith, not only in France but also subsequently in Britain and America.

During the early 1890s Georges Rouault (1871–1958) studied at the École des Beaux-Arts under Gustave Moreau, who urged his students to seek a spiritual rather than a literal truth in their work. Moreau played a large role in Rouault’s life, and the teacher’s death (when Rouault was twenty-seven) marked a turning point in the young painter’s life.105 During that time he sought out a priest for instruction and preparation for his first Communion. In 1901 he spent time in a commune with Huysmans and other artists and writers, but it was his encounter with the writer Léon Bloy in 1904 that was to have the major impact on his life. Bloy, who was also the catalyst in the conversion of Jacques and Raïssa Maritain, wrote a series of novels that featured human suffering as mystically expressive of the suffering of Christ. Though Bloy never understood the darkness of Rouault’s painting, the painter remained a devoted friend, visiting him every Sunday until Bloy’s death in 1917. The influence of Bloy on Rouault’s work is evident, not least in his view of sacred art. In his Soliloques, Rouault writes of Bloy: “It is not always the subject that inspires the pilgrim, but the accent that he puts there, the tone, the force, the grace, the unction. That is why some so-called ‘sacred art’ can be profane.”106 The darkness of Rouault’s earlier work was not appreciated by the art establishment either, and he toiled in relative obscurity until the 1920s. According to Stephen Schloesser, a turning point came with a review by critic Michel Puy in 1921. Puy recognized that “Rouault is a religious spirit. Under the human rag, he discerns the soul. . . . [In the clown he explores] ‘a mask whose simplicity is at one and the same time comic and tragic: . . . beneath the illusory presence, humanity subsists with its true nature.’”107 He was able to capture this, Schloesser says, because “Rouault’s spirit was sacramental.”108 In paintings such as Christ in the Suburbs (1920), he often painted spare landscapes where Christ was seen with his disciples, or as here with children. But Christ’s strong presence, at the center of the picture, is mirrored by the way a light in the richly colored sky with its small sun illumines the empty and often dark streets.

Jacques and Raïssa Maritain met Rouault for the first time in 1905. Raïssa recalls sitting with her husband listening to Rouault and Bloy discuss “every question about art.”109 The relationship with Bloy resulted in the Maritains’ baptism in the summer of 1906. Given Bloy’s influence and the fact that Rouault (who was eleven years Maritain’s senior) was well known for having exhibited with the Fauves, these discussions were surely significant in the evolution of their own thinking about art and faith. Raïssa notes that it was in thinking of Rouault especially that Jacques wrote his influential book Art and Scholasticism, first published in 1920.110

Jacques Maritain has probably done more than any other person to provide an intellectual justification for the Christian artists working in the modern styles, though he has yet to receive the critical attention in this respect that he deserves.111 In Art and Scholasticism, his first work, Maritain laid out a theological foundation for understanding art in a holistic way that was based on the philosophy of medieval theologian Thomas Aquinas. With an emphasis that may have been dependent on Rouault, who identified so strongly with medieval artisans, Maritain championed the medieval notion of artmaking as ordered toward a particular practical end.112 The artist works alongside God the creator because she or he works necessarily with the “treasure house” of the creation. Moreover, artists seek to produce, “by the object they make, the joy or delight of the intellect through the intuition of the sense.”113 The artist of faith never stopped with forms or colors of things alone, as the symbolists seemed to do. The images must point beyond themselves; they must become signs of something else. “The more the object of art is laden with signification . . . the greater and richer and higher will be the possibility of delight and beauty.”114 Such beauty ultimately reflects a Divine beauty, Maritain believed; though made of creation, it draws the soul beyond the created order. In his important discussion of Maritain, Stephen Schloesser argues that this thinker succeeded in reconciling ancient and modern discourses about art. He saw the form as deeper than imitation, something he learned from Aquinas’s notion of the splendor of form, and he saw the subject of art as a “sensible sign” of this, something that captured the sacramental depths of creation.115

Later, in a series of lectures given in 1952, Maritain drew out many of the implications of this early work. Art, he said, is “the creative or producing, work-making activity of the human mind,” which generates experiences of beauty wherever there is a genuine interaction between humanity and nature.116 The critical notion of the self in Western art, he claimed, emerged in relation to theological formulations of the person of Christ: the self was first seen as an object in the revelation of Christ’s divine self (especially in the great councils that defined that self), then humanity came to understand the self as subject, and finally it came to see the creative subjectivity of the person as poet or artist.117 So even in the modern promotion of the self, Maritain claimed, the artist cannot escape the influence of Christ. Modern art then brings with it a new potential by which the inner meaning of things is grasped through the interaction with the artist’s self; both are manifest in the work.118

This theological grounding of the artist’s work, both in creation and in the selfhood of Christ, makes possible a striking view of the process of artmaking. Working out a lived logic (habitus), the artist furrows into the inner workings of nature, “in its own way the labor of divine creation.”119 This “knowledge-with” things, Maritain termed “connaturality.” That is, the soul of the artist seeks itself by “communicating with things,” effecting knowledge through “affective union.”120 Beauty emerges out of this “connatural” knowledge of the self and things. It “spills over or spreads everywhere, and is everywhere diversified.”121 Notice that beauty emerges from the work—from below, as it were, not from above. Even if it reflects the radiance of the transcendent, it is a spontaneous product of the affective union of self and nature, which comes to expression in the work. This unique union suggested both the promise of modern art and also its peril. Modern art’s temptation, Maritain believed, was to favor the antirational rather than the superrational, to seek beauty at the expense of the beauty of the human form, or to choose the self over the thing seen—distortions amply illustrated in the history of modern art.

Maritain’s genius was to create a language and a way that artists could see themselves as both fully modern and yet nourished by the Catholic tradition, especially the Thomism of the Middle Ages. His influence was considerable among writers and artists in France. While standard treatments of this period have overlooked his influence, voices recently have been raised to argue for the lasting impact of the Catholic revival on avant-garde art in France. Gino Severini (1883–1966), for example, when he had become disillusioned with the futurist quest to adapt cubist forms to movement, met Jacques Maritain (and read Art and Scholasticism) in 1923.122 Having converted to Catholicism in 1919, he was moved by his encounter with Maritain. They shared, among other things, an early encounter with Henri Bergson, though they later repudiated his vitalism. Severini had already argued in his Du cubisme au classicisme (1921) that artists needed a new sense of space, but he was searching for a more universal foundation for this. Maritain (and to a lesser extent Maurice Denis) helped him see that the artist could “recreate” the universe “according to the laws by which it is determined,” and that art could be productive action.123 Severini was able to go on to “construct an aesthetic framework in which the formal language of modernism, the harmony provided by the Church and the craftsmanship of the past would co-exist and mutual[ly] benefit one another.”124

Later, Albert Gleizes (1881–1953), who had been an important contributor to cubism, returned to Catholicism in 1941 and sought to renew sacred art in the language of modern art—especially of cubism to whose principles he remained faithful throughout his life. Gleizes felt that the modern language of abstraction was uniquely suited to express a pure spirituality. His project might be summed up, in a way that recalls Maritain, as the attempt to integrate the formal discoveries of cubism with the religious sensitivities of the Middle Ages.125 Gleizes’s influence on the sacred in French art during the second half of the twentieth century remained strong.

One who followed in the way forged by Gleizes was Alfred Manessier (1911–1993). In the late 1930s a group called Témoignage (Testimony) kept alive Christian mystical ideas nourished by Thomism and by Maritain. While Manessier showed with this group in the 1930s, it was not until after the war had begun, in 1943 following a period in a Trappist monastery, that he formally converted to Catholicism. From this point on he worked to develop means to express a greater interiority and to advance the ideas of Christian mysticism and Thomism. In this later period he oriented his work more toward specifically Christian themes, though he worked with forms abstracted from sensations of the outside world. Like Gleizes, he preferred nonfigurative means. As he put it, “Non-figurative art seems to give the opening at present by which a painter can better move toward reality and take conscience of what is essential in himself.”126 Both Gleizes and Manessier demonstrate that the ideas of Maritain, and the explicit expression of religious faith, were present in some of the best work that is associated with the School of Paris.

The influence of the Catholic revival can be seen in significant members of the School of Paris, but what about the more influential artists of the century, Cézanne and Picasso? There is no doubt about the influence of these artists on the twentieth century, yet very few have proposed that religion has played any significant role for either. Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) was a reclusive figure, working alone in Aix en Provence (in the South of France) and supported grudgingly by his banker father. His correspondence reveals little about his personal life—as he believed that the person behind the work should stay out of sight,127 and he was impatient with conversations about theory. His advice to younger artists was simple: study nature and seek to discover its secrets. When pressed he would say, study it some more. But his mode of working with nature was anything but simple. He wanted to paint from nature, but with the substance of the great masters of the past—to redo Poussin, as he put it, but from nature. This involved a meticulous study of subjects to discern their structures—cylinder, sphere, cone. He sought, as Rookmaaker put it, “the universal ideas that ordered what he saw.”128

Though Cézanne worked from nature, he liked to visit the Louvre to seek confirmation of his pictorial researches. “The Louvre is the book in which we learn to read,” he told Émile Bernard.129 Werner Haftmann reports that Veronese’s Marriage at Cana filled Cézanne with enthusiasm: “It is beautiful and alive,” the artist wrote, “and at the same time it is transposed into a different yet entirely real world. The miracle is there, the water is transformed into wine, the world into painting.”130 Transforming the world into painting serves as a useful shorthand for Cézanne’s goals. Haftmann characterizes the results as something that more religious epochs would call “revelation.” For as Cézanne liked to say: “Nature is more depth than surface, the colors are the expression on the surface of this depth; they rise up from the roots of the world.”131

Little wonder the younger artists were struck when they came upon his work in the basement of Père Tanguy, who sold artist supplies in Paris in the 1880s and 1890s. Tanguy sometimes allowed Cézanne to leave his work there in exchange for paint and brushes. Pissarro was an early admirer and urged van Gogh to study these careful compositions; Tanguy used them to give young Émile Bernard art lessons. The artists were smitten—never mind that Cézanne’s work was hard to sell, brought only half the price of a Monet and was repeatedly spurned by the salons.132

A look at a work from 1884–1885, Farmhouse and Chestnut Trees at Jas de Bouffan (fig. 3.4), gives some indication of what these artists found striking. A pleasant house, the Cézanne’s family estate in the south of France, is framed by trees and set back amidst a loosely sketched lawn. There is a tension set up between the trees and the solid triangles and rectangles of the house. But the very visual tensions—between solid and blotched colors, and between lightly drawn trees and the strong structure of the building—reach out to challenge the viewer. The imagery dissolves into lines and colors on a flat surface, but one that plays and skips as it is seen, pushing the possibilities of color and lines in a new direction.133

Standing before this picture, one recalls the words of Walter Benjamin before a similar painting in Moscow:

As I was looking at an extraordinarily beautiful Cézanne, it suddenly occurred to me that to the extent that one grasps a painting, one does not in any way enter into a space; rather this space thrusts itself forward, especially in various specific spots. . . . There is something inexplicably familiar about these spots.134

The work Cézanne’s composition performs on the viewer may suggest one of the ways that he became influential on the cubists who followed him.

Figure 3.4. Paul Cézanne, Farmhouse and Chestnut Trees at Jas de Bouffan, 1884–1885

His reputation slowly began to grow. After his death, a large exhibit opened in Paris in 1907 that proved revolutionary to the cubist generation. And since then Cézanne has come to displace even van Gogh and Gauguin as “the godfather of modern art.”135 What accounts for this influence? There are many accounts of his formal dependence on Monet and Pierre-August Renoir, and even on Georges Seurat. Like them he had abandoned the variations in light and dark, substituting shifts won through juxtaposition of separate strokes of color. But unlike them he sought to build up the structure of his forms through the application of more classical methods of composition, which he had learned from the masters.

But as Robert Herbert notes, “Analyses based mostly on aspects of formal structure are seductive, but they deny Cézanne’s range and depth.”136 And this range and depth may have had deeper roots. Cézanne was notably reticent to reveal much about his personal life—indeed the publication of Émile Zola’s fictionalized life of Cézanne, L’Oeuvre (The Work) (1886), caused Cézanne to break with his old childhood friend. But there are significant hints that have yet to be explored. Not surprisingly, it was the irrepressible Émile Bernard who sought to draw out Cézanne late in his life. Bernard had long been an admirer of the older painter and had published an article on him in 1892. But it wasn’t until 1904, on his return from a trip to Egypt and Italy, that Bernard, with his wife and two children, stopped off to meet Cézanne in Aix. Bernard tried to open conversations on a variety of philosophical issues, in which Cézanne took little interest. But Bernard did succeed in getting the aging artist to write down his thinking in some detail. A letter written April 15, 1904, provides the most detailed explanation:

Treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone, putting the whole in perspective, so that each side of an object, within the plan, is directed toward a central point. The lines parallel to the horizon give the extension, whether of a section of nature, or, if you prefer, of the spectacle the Pater Omnipotens Aeterna Deus [omnipotent Father, eternal God] lays out before us. The lines perpendicular to this horizon give the depth. Because nature, for us humans, is more depth than surface.137

Cézanne goes on to note how important is the choice of colors for evoking this feeling of depth—reds and oranges for the surface, and enough blue to make one “sense” the air. Significant is the detailed sense of structure, line and color to which his research had led him. But embedded in these descriptions is a reference to the ground of this in the Creator—perhaps in response to Bernard’s prompting.