Plate 3. Caspar David Friedrich, Monk by the Sea, 1808–1810

The Greeks achieved the highest beauty in forms and figures at the moment when their gods were dying; the new Romans [i.e., Raphael and Michelangelo] went furthest in the development of historical painting at the time when the Catholic religion was perishing; with us too something again is dying.

Philipp Otto Runge1

The protagonists [of modern art] withdraw to the last line of defense. It is a question of the ground plan and the works all contain a philosophy of the ground plan. . . . The painters and poets become theologians.

Hugo Ball2

For much of the twentieth-century—and certainly in the 1960s and 1970s when Rookmaaker was doing his most influential work—the dominant narratives of modernism were especially preoccupied with France. As argued in the previous chapter, the typical secularist framing of these narratives deserves reconsideration in light of the ways that French modernism was shaped by, and carried the influences of, Roman Catholic thought and practice. However, over the past few decades numerous scholars have demonstrated that the francocentrism of these narratives also needed to be reconsidered. The history of modern art has since rapidly expanded to account for the ways that it unfolded well beyond the purview of Paris, in each case rendering the modernist project in somewhat different terms and in the context of somewhat different social pressures.3 This is of particular interest here because these different terms and pressures (and their respective modernisms) involved different religious traditions and frames of reference. In this chapter we shift our focus especially toward Germany and Holland, exploring a handful of ways that modern art developed within contexts that were particularly (in)formed by Protestantism.

Robert Rosenblum’s 1975 book, Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition, provides a valuable point of entry through which to launch this investigation.4 The premise of his study is that “there is an important, alternative reading of the history of modern art which might well supplement the orthodox one that has as its almost exclusive locus Paris, from David and Delacroix to Matisse and Picasso.”5 Rosenblum protested that the Parisian narrative of modernism—which had dominated the construction of nineteenth- and twentieth-century art history in his time—produced too narrow an understanding of the driving concerns and lineages of modern art,6 construing them primarily in terms of (a sociopolitically charged) formalism.7 Supplementary to this narrative—or perhaps over against it—Rosenblum wanted to track an “eccentric Northern route that will run the gamut of the history of modern painting without stopping at Paris.”8 He acknowledged that stating things this way might be too “schematic,” evoking a “too simple-minded polarization between French and non-French art,” but this polarization provides a useful heuristic device to the extent that it allows the “glimmers of a new structure of the history of modern art” to come into sharper focus.9

The distinguishing feature of Rosenblum’s northern route is that its primary points of navigation are “the religious dilemmas posed in the Romantic movement.”10 This has two immediate implications for the way his narrative unfolds: First, he argued that the engines of northern modernism—the driving cultural pressures and concerns that shaped it—were more theological than political, fueled primarily by the problem of “how to express experiences of the spiritual, of the transcendental, without having recourse to such traditional themes as the Adoration, the Crucifixion, the Resurrection, the Ascension, whose vitality, in the Age of Enlightenment, was constantly being sapped.”11 He avoided telling a simplistic secularization narrative, but Rosenblum’s starting point was an acknowledgment of the weakening of traditional Christian thought and practice in modern North Atlantic societies, primarily in the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries. He believed that this weakening directly corresponded to an unprecedented shift in cultural weight and explanatory power from religion to the natural sciences, a shift generally accelerated by the development of analytic philosophy, historical materialism and higher biblical criticism. Human spirituality and a general regard for a transcendent ground of being have persisted throughout this shift, argued Rosenblum, but they had to do so in fugitive forms that could no longer assume a common vocabulary, iconography and canon of narratives once provided by Christianity. And thus Rosenblum’s narrative of modernism is consistently told in terms of an artistic reworking of spirituality into dechristianized (or at least post-Christian) forms. He reached for a variety of metaphors to make the point: the inaugural events of modern art are constituted by “secular translations of sacred Christian imagery,” “transvaluations of Christian experience,” “transpos[itions] from traditional religious imagery to nature,” the “relocation of divinity in[to] nature, far from the traditional rituals of Christianity” and so on.12 By borrowing his analogies from linguistics (translation), ethics (transvaluation), music (transposition) and geography (relocation), Rosenblum argued that there are core spiritual meanings, intuitions and sensitivities that are sustained and alive throughout northern modernism, despite their radical change of form.13 Though once supported by Christianity, this core spirituality can—and presumably now must—function in the normative dialects (or values, musical keys and localities) of secular modernity. In short, for Rosenblum modernism was an essentially theological enterprise that took shape within the cross-pressures of theological crisis.

Second, the theological dilemmas of northern modernism were particularly Protestant in their construction. The lines of the “Northern Romantic tradition” that Rosenblum traced from early nineteenth-century Germany to late twentieth-century North America run through regions and lineages that were historically deeply rooted in Protestant thought and culture, including Holland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and England. The crises of representation that were constitutive to modernist art (in all of its strands) were grappled with in particularly Protestant terms as they traveled along these northern lines of influence. A rapid disintegration of Christian iconography occurred throughout Euro-American cultures, but, according to Rosenblum, “in the Protestant North, far more than in the Catholic South, another kind of translation from the sacred to the secular took place, one in which we feel that the powers of the deity . . . have penetrated, instead, the domain of landscape.”14 The inherently decentered and perpetually decentering character of Protestantism—ecclesia reformata, semper reformanda (church reformed, always being reformed)—historically coupled with strong iconoclastic impulses toward ossified religious imagery, created an atmosphere in which modernity was experienced with different cultural cross-pressures and different critical flashpoints than in predominantly Catholic (or Orthodox) regions. And as Rosenblum rightly noted, in the visual arts these pressures and flashpoints tended to be especially concentrated on the theologically charged practices of landscape painting.

The problem is that Rosenblum generally misinterpreted this theological atmosphere and the pressures it produced, and thus he consistently drove conceptual wedges between the “Romantic tradition” and orthodox Christianity where there needn’t necessarily be any. His thesis was that the primary ambition of northern modernism was to produce a post-Christian theological framework that could sustain “a sense of the supernatural without recourse to inherited religious imagery.”15 He overlooked the distinctly Protestant framework of this “sense” and instead characterized the result as a pantheistic and privatized theology that was “usually so unconventional in its efforts to embody a universal religion outside the confines of Catholic or Protestant orthodoxy that it could only be housed in chapels of the artists’ dreams or in a site provided by a private patron.”16

Charles Taylor offers a helpful corrective to this reading of the romantic period. He agrees that long-accepted Christian assumptions about history and cosmology were being revised or abandoned during this period, and as a result “certain publicly available orders of meaning” were unraveling and defaulting toward more private languages of experience and “articulated sensibilities.”17 He also accepts that this had deep consequences for the arts: as traditional symbolic orders weakened, artists increasingly had to ground their work in some “personal vision” by which meanings could be “triangulated” within the “forest of symbols” that remained.18 The resulting artworks may have been symbolically nontraditional, and the metaphysical and ontic commitments that they entailed were often vague, but Taylor argues that it is a mistake to call these works post-Christian tout court. The new symbols constructed by these artists were not made up out of whole cloth, nor were they simply repudiations of traditional Christian faith. Rather, they were developed as part of the struggle “to recover a kind of vision of something deeper, fuller” in the context of modernity’s fragilizing of religious meaning.19 And in the course of this struggle, Taylor concludes, “God is not excluded. Nothing has ruled out an understanding of beauty as reflecting God’s work in creating and redeeming the world. . . . The important change is rather that this issue must now remain open.”20

The aim of this chapter is to further explore this struggle to recover a vision of “something deeper, fuller” as it was inherited from the northern romantic tradition and worked out through modernism. We will reconsider a handful of the key artists in Rosenblum’s narrative of northern modernism while challenging his assumptions about the theological implications of their work. And in the process we will interpret these artists’ works in a way that also sharply diverges from Rookmaaker’s treatment of them, reframing the theological content of their work in much more constructive terms. We propose that many of the central developments in northern modernism are better understood from within Protestant theology rather than outside of it, particularly with respect to Protestant thinking about the “givenness” of creation and the eschatological redemption of all things.

Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840) is mostly ignored in Rookmaaker’s genealogies of modern art,21 but he is of central concern for Rosenblum, who designates Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea (1808–1809) as the “alpha” of the northern modernist painting tradition—to which Mark Rothko’s Green on Blue (1956), and ultimately the Rothko Chapel in Houston (1964–1971), will serve as an “omega.”22 In fact, Friedrich’s Monk is the inaugural moment for Rosenblum’s narrative in much the same way that Jacques-Louis David’s Death of Marat (1793) is for T. J. Clark’s powerful francocentric history of modernism.23 Clark sees David’s Marat as pictorially embodying a profound sense of historical and political contingency (the painting punctuated a crucial moment in the French Revolution), which he regards as fundamental to modernist painting.24 Rosenblum similarly reads Friedrich’s painting as embodying and articulating a particularly intense and distinctly modern sense of contingency, but this is a contingency of theological (more than political) crisis, arising from “his need to revitalize the experience of divinity in a secular world that lay outside the sacred confines of traditional iconography.”25

Monk by the Sea (plate 3) depicts a man (probably the artist himself)26 wearing a Capuchin monk’s habit, standing alone on a beach with his back to us. From the thin strip of shoreline in the foreground, the monk peers out over the vastness of a cold, dark sea, which extends ever outward beneath the infinitely greater vastness of the heavens. Other than a few whitecaps, nothing appears on the expanse of the waters and nothing transgresses the horizon. The sandy foreground is mostly desolate, the sea is blank and heavy clouds sit on the water so that the darkest regions of the painting are gathered along the horizon. The lone monk is dwarfed by the expanses of land, sea and sky (and the expanse of the canvas itself), but all these realms seem to squeeze toward him, creating a strange spatial compression. His placement in the canvas (approximately one-third the distance from the left edge) coincides with both the highest point of the shape of the beach and the lowest point of the sky visible beyond the clouds. The shape of the sea is mirrored in the darkest band of fog that sits on the horizon, and both bands are at their narrowest where the tiny monk stands on the shore—thus pushing all the visual pressure in the image toward the extremely charged gap between the top of the monk’s head and the horizon toward which he looks.

Plate 3. Caspar David Friedrich, Monk by the Sea, 1808–1810

Above and beyond the monk’s head the horizon forms a sharp, unbroken line across the canvas, creating a provocative spatial ambiguity that anticipated much later modernist painting: this horizon line simultaneously rushes toward us—as a flat geometric division on the surface of the painting, parallel to the top and bottom edges—and rushes infinitely away from us as the furthest limit and vanishing point of our vision, where the earth’s curvature pulls the seemingly endless sea out of view. Kristina Van Prooyen highlights a further spatial ambiguity, noting that the vast expanse of the sea occupies roughly the same amount of the painting’s surface as does the beach—a visual paradox that “points to the metaphysical problem of the picture”: namely, that all efforts to intellectualize and rationalize “the endlessness of nature” can only happen from a position that is thoroughly human and thus thoroughly located.27

X-ray and infrared studies of the painting reveal that Friedrich had originally painted at least two ships on the sea with their masts extending above the horizon—both of which he eventually painted out. Rosenblum argues that our knowledge of Friedrich’s decision to remove these boats only amplifies our sense of just how “daringly empty” this landscape really is: empty of all objects, ornamentation, narrative or focal points, other than the lonely penitent who stands “on the brink of an abyss unprecedented in the history of painting.”28 And for Rosenblum this abyss represented a breach in human understanding, provoking “ultimate questions whose answers, without traditional religious faith and imagery, remained as uncertain as the questions themselves.”29 Ultimate questions are certainly in play here, and perhaps their unanswerability is implied, but it is unclear why we should force Friedrich to stand—or force ourselves to stand—to face those questions “without traditional religious faith and imagery.” Friedrich described this painting in a letter:

Even if you [presumably addressing himself in the second person] ponder from morning to evening, from evening to dawn, you will not fathom and understand the impenetrable “Beyond”! With overconfident self-satisfaction, you think you will be a light for progeny, will unriddle the future. People want to know and understand what is only a holy conjecture, only seen and understood in faith! Your footsteps do indeed sink deep into the lonely sandy beach, but a soft wind blows over them and your footsteps will disappear forever: this foolish man full of vain self-satisfaction!30

For Friedrich this painting thus advocates for a faith chastened by a radical epistemic humility (vis-à-vis the confident rationalism of the Enlightenment), which is insistently acknowledging and “foregrounding” the limitations of human understanding.31 He highlights at least three such limits: (1) The narrow strip of beach creates a compressed foreground—Friedrich wants us to feel the particularity and locatedness of personal experience both spatially (feel your heavy feet sinking into this particular sand) and temporally (watch as these seemingly deep footprints disappear, as have all those who walked here before). (2) The edge of the water marks another such limit: from our position on this side of that boundary, we are confronted with the vast expanses of sea and sky that humans can manage and traverse only in limited ways and only with great difficulty. These realms that extend indefinitely “beyond” this shoreline are nameable and imaginable, even if only from afar or in abstract ideas, but Friedrich wants to elicit an acknowledgment that the reality of these creaturely realms always exceeds and outstrips our capacities for action, perception and understanding. (3) Friedrich is ultimately interested, however, in marking a limit that is “impenetrable”: one in which the “Beyond” is an Unspeakable, an Unthinkable, an infinite and uncreated No-thing. In Monk by the Sea this limit is most profoundly marked not by the shoreline or the expanses of sea or sky but by the horizon from which these realms appear and toward which they recede. The very possibility of a horizon signifies the beginning and the end of perception (and cognition), beyond which we can only gesture “in faith” toward that which is invisible, unpronounceable and unthinkable—“a holy conjecture.” Indeed, perhaps the penitent humility of a Capuchin is precisely the posture from which such things might be approached.

The most consistent strategy Friedrich uses to evoke these “beyonds” is to set a limited foreground over against a vast background, creating a breach between the two. In Monk this gap is ultimately ontological: from the concrete “here” of the foreground the monk peers toward an utterly open horizon that allegorizes the unknowable Beyond from which being itself is given. In many of his other works, however, this beyond is also—sometimes even primarily—eschatological: the breach between foreground and background functions as a gap between a “here-and-now” and a future “elsewhere-and-someday.” Winter Landscape with Church (1811) is perhaps the most overt example in which the distance into the background is both metaphysical (beyond immediate material conditions) and temporal (beyond immediate historical conditions), but this same pattern can be found throughout his work, in paintings like Mountain with Rainbow (1809–1810), Two Men Contemplating the Moon (1819), Woman Before the Rising Sun (c. 1819) or The Abbey in the Oakwood (1809–1810).

Friedrich painted The Abbey in the Oakwood (fig. 4.1) as the companion to Monk by the Sea. The two canvases are the same size and were first exhibited as a pair in the 1810 exhibition of the Prussian Royal Academy in Berlin. Upon Friedrich’s request, Monk was hung above Abbey, and together they form complementary approaches to the same questions and concerns. In Abbey monks in procession carry a coffin toward the open doorway of a ruined Gothic church,32 which stands on the vertical centerline of the painting. Immediately below the ruined façade, a freshly dug grave lies open in the middle of the foreground: the funeral procession passes it by as if to assert that the grave is neither the object of their ceremony nor the destination of this dead brother. A forest of leafless trees presides over numerous grave markers that jut through the snow, marking the old graves scattered beneath the surface of the cold ground. Wieland Schmied bluntly summarizes the scene: “The church is destroyed, the graveyard abandoned, nature dead. Still the monks are celebrating the mass” as if the holy were to be encountered precisely within this destruction, abandonment and deadness.33 Reaching up from the dark, earthy lower portion of the painting, the derelict architecture stops just short of the halfway point of the canvas, and the entire top half of the painting is given over to a sky that is losing the light of the setting sun. As the sunlight withdraws, the faint form of a waxing moon appears in the sky alongside the evening star.

Figure 4.1. Caspar David Friedrich, The Abbey in the Oakwood, 1809–1810

This decrepit manmade structure was built to celebrate the glory (fullness) of God, but it is now a wreckage, undone by the centuries-long inertia of social transformation and natural entropy. The “soft wind” that Friedrich had in mind erases both footprints and cathedrals alike. And in Abbey the two are in fact drawn together: the ruined body of the man being carried through the doorway is directly analogized with the broken body of the cathedral; both are images of God that are finally unable to generate their own lives or to contain that Life to which they refer. Both human life and human theology are thus faltering pointers toward realities beneath or beyond what is speakable and thinkable. And yet Friedrich affirms their pointing. As Joseph Leo Koerner notes: “The Gothic monument, while now a jagged ruin, is perfectly centered and displayed en face, as if to recollect for us its original symmetry. . . . It is the canvas’s symmetry, its straight edges, rectangular format and measurable midline, that recovers the cathedral’s order within dissolution.”34 Friedrich’s cathedral is simultaneously broken down (by the passage of time) and held fast (by that which is eternal).35 Whereas Monk pushes the religious seeker to the brink of the abyss, Abbey pushes him to the brink of death; and, in both, religious structures and rituals are found outstripped by the unspeakable Beyond to which they point.36

Koerner contends that “Friedrich empties his canvas in order to imagine, through an invocation of the void, an infinite, unrepresentable God. The precise nature of this divinity, as well as the rites and culture that might serve it, remain open questions, yet the religious intention in Friedrich’s art is unmistakable.”37 This open questionability of Friedrich’s religious intentions has, however, led to deep disagreements about the theological implications of his work. Rookmaaker, for instance, regarded it as a kind of despairing protoexistentialism. In his view, Friedrich’s paintings “depicted humans as trivial and insignificant . . . small and lonely figures in a world of deathly loneliness and abandonment.”38 And thus he believed that Friedrich’s paintings articulated a quintessentially modernist experience of the world as “alien and un-heim-isch, a world in which the modern person does not feel at home [heim is German for ‘home’]. . . . Far from affording them the experience of freedom, such emptiness seems instead to oppress modern viewers, since they know themselves to be lost in it.”39

Quite to the contrary, many other scholars have aligned with Rosenblum, interpreting Friedrich’s work in terms of a thoroughgoing pantheism. Friedrich sometimes sounds as though the pantheist label might in fact fit: “The divine is everywhere, even in a grain of sand. . . . The noble person (a painter) recognizes God in everything, the common person (also a painter) perceives only the form, but not the spirit.”40 Everything hinges, however, on how we understand Friedrich’s conception of God being “in” all things.41 Koerner argues that interpreting such statements as pantheistic is irreconcilable with the paintings themselves, which actually “express a thwarted reciprocity with the world”—an irresolvable “disparity between the finite and the infinite, consciousness and nature, the particular and the universal.”42 These paintings “indicate a negative path, in which God cannot be found in a grain of sand, but at best in the unfulfilled desire that He be there.”43 Or perhaps it would be better to say that the “negative path” of these paintings is that they insist on the infinite disparity between God and creaturely existence while simultaneously insisting that God utterly permeates and sustains the creaturely being of every molecule and every grain of sand. Friedrich’s paintings are thus not concerned with pantheistic Oneness as much as they engage a human “longing for the infinite”—a desire to span the infinite interval between the creaturely and the Creator.44 Rosenblum recognizes this interval in Friedrich’s work, but he confusingly tries to collapse it into pantheistic terms, arguing that Monk, for instance, establishes “a poignant contrast between the infinite vastness of a pantheistic God and the infinite smallness of His creatures.”45 Koerner’s point is that if any such contrast is in fact established, then talk about a pantheistic Unity becomes untenable. Unfortunately, this confusion persists throughout Rosenblum’s work.46

And actually much rides on this point. The ways we interpret the theological significance of Friedrich’s work have implications for how we revise Rookmaaker’s (francocentric) declinist narrative and for how we retrace Rosenblum’s northern modernist narrative. Rosenblum wants to identify a “Romantic amalgam of God and nature” that begins with Friedrich and continues to drive avant-gardism into the 1970s,47 but Koerner provides a necessary correction:

Against the pious cliché of an annihilation of self before Creation, Friedrich fashions a more difficult vision, one in which the experiencing self is at once foregrounded and concealed, and in which God, submitted to a Hebraic iconoclasm born perhaps from the artist’s own Protestant spirituality, is shown in His absence, as the image of His consequences.48

Theologian Wessel Stoker clarifies further: “Friedrich’s religious landscapes are not pantheistic but theistic. He stands in the tradition of physicotheology, which viewed nature, as the creation of God, as a testimony to God’s presence.” The sharp horizontal boundary between sea and sky in Monk marks “a clear line separating the human being from the infinite,” but it is a separation grounded in a “Christocentric, Lutheran belief that heaven and earth are closely connected to each.”49

One of the reasons that Rosenblum—and Rookmaaker, for that matter—misreads the theological substance of Friedrich’s work is that he neglects to adequately trace the lines of Friedrich’s thinking back to their theological sources—namely, to German Pietism on the one hand and to seventeenth-century Dutch Reformed painting on the other. Friedrich’s deviation from traditional Christian subject matter was in fact driven by Protestant theology, rather than by any subtraction or deterioration of Christian belief. Werner Hofmann rightly argues that “it was from his Lutheran-Evangelical faith that he derived the basic tenets that determined his artistic decisions.”50

Friedrich was a Pietist. Through his first painting teacher, Johann Gottfried Quistorp, he was introduced to the celebrated Lutheran theologian, pastor, poet and literary scholar Ludwig Gotthard Kosegarten (1758–1818), who had a lasting impact on Friedrich’s theological imagination.51 Kosegarten preached a Moravian “theology of the heart” that sought personal experience of and relationship to God—with or without the mediation of the church.52 He held regular worship services outside on the shores of Rügen, a large island in the Baltic Sea directly north of Friedrich’s hometown of Greifswald. These services were celebratory but liturgically sparse, accompanied only by the much grander “trumpets of the sea and the many-voiced pipe organ of the storm.”53 Kosegarten’s famous Uferpredigten (shore-sermons), published posthumously, poetically rendered all of creation as the temple of God, who is everywhere sustaining and shining through all things. Kosegarten advocated a humble attentiveness to the created world, regarding God as simultaneously radically immanent (closer than one’s own thoughts) and wholly transcendent (not equivalent to or containable within any creaturely aspect or form). In many ways Friedrich’s paintings function as visual analogues of Kosegarten’s shore-sermons. In fact, Friedrich’s famous contemporary Heinrich von Kleist was specifically struck by the “Kosegartenian effect” of Monk by the Sea.54

Following his studies at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen from 1794 to 1798, Friedrich returned to Germany and settled in Dresden, where he quickly became associated with a group of prominent romantic thinkers, including Gerhard von Kügelgen, Ludwig Tieck and Novalis—all of whom were friends of the enormously influential romantic theologian F. D. E. Schleiermacher (1768–1834). The extent to which Schleiermacher and Friedrich knew each other personally is uncertain, although the theologian seems to have visited the artist in his Dresden studio at least once in 1818.55 And given their mutual friends, Friedrich almost certainly had some level of familiarity with Schleiermacher’s writing, including his book On Religion: Speeches to Its Cultured Despisers (1799). Indeed, Friedrich’s Monk could hardly find a more striking commentary than in the words Schleiermacher had published less than a decade earlier: “When we have intuited the universe and, looking back from that perspective upon our self, see how, in comparison with the universe, it disappears into infinite smallness, what can then be more appropriate for mortals than true unaffected humility?”56 Fundamental to Schleiermacher’s theology is the notion of Eigentümlichkeit (individuation, particularity, peculiarity), in which each person must meet God in the particularity of his or her own conscious experience of the world. This same concept was central for Friedrich and his circle. In fact Kügelgen deployed precisely this concept in his 1809 defense of Friedrich’s controversial Cross in the Mountains; and in his own fragmentary writing Friedrich speaks of the “temple of Eigentümlichkeit,” in which one’s conscience must be tuned to “harken more to God than to man.”57 For both Schleiermacher and Friedrich this hearkening includes a careful attentiveness to the world as it presents itself.

In addition to his roots in German Pietism, we also need to account for the influence of Dutch Reformed painting. While studying in Copenhagen, Friedrich had access to a large collection of seventeenth-century Dutch painting at the Royal Picture Gallery, where he developed a deepened sense of landscape painting as a theological project. And upon returning to Dresden, Friedrich had access to further important examples of Dutch landscape painting, including Jacob van Ruisdael’s Jewish Cemetery (c. 1654–1655), which provided a striking precedent to Friedrich’s Abbey.58 Rosenblum directly linked Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea to Dutch “marine painting,” which is “the tradition most accessible to and compatible with Friedrich,”59 but apparently he interpreted this link strictly in stylistic terms, stripped of any theological content. Or rather, he regarded Dutch painting as already theologically bare: “That [Friedrich] achieved what were virtually religious goals within the traditions he inherited from the most secular seventeenth-century Dutch tradition of landscape, marine, and genre painting is a tribute to the intensity of his genius.”60 This betrays a deep misunderstanding of the theology of Dutch painting, and it leads to further misinterpretations of the ways Friedrich pursued his “religious goals”—and thus of the theological significance of large portions of the northern modernist tradition that followed.

The traditions of seventeenth-century Dutch landscape (and seascape) painting grew out of deeply Protestant—particularly Calvinist—theological thinking. In his Institutes of the Christian Religion John Calvin staged a multipronged theological polemic against the idolatrous human tendency “to pant after visible figures of God, and thus to form gods of . . . dead and corruptible matter. . . . For surely there is nothing less fitting than to wish to reduce God, who is immeasurable and incomprehensible, to a five-foot measure!”61 Indeed, he contended that “God’s glory is corrupted by an impious falsehood whenever any form is attached to him”; only “God himself is the sole and proper witness of himself.”62 This corruption is most problematic in depictions of God, but Calvin thought that this falsehood beleaguers imagery of any religious subject matter to the extent that (1) it supplants the study of Scripture itself or (2) it “invite[s] adoration” of itself.63 And thus depictions of biblical narratives, Christ, Mary and the saints—any visual figurations of religious subjects—are inherently problematic.

After pages of sharp criticism toward such images, Calvin devoted a single paragraph to sketching a constructive theology of visual art, which proved to be profoundly influential in opening the way forward for Reformed artists:

And yet I am not gripped by the superstition of thinking absolutely no images permissible. But because sculpture and painting are gifts of God, I seek a pure and legitimate use of each. . . . Therefore it remains that only those things are to be sculptured or painted which the eyes are capable of seeing: let not God’s majesty, which is far above the perception of the eyes, be debased through unseemly representations.64

Packed into that last sentence are the contours of an entire Protestant aesthetic that carefully attends to the limits of perception (both spatial and temporal).65 When devout Calvinists turned away from making what they considered to be idolatrous representations of biblical subject matter, they turned their canvases toward those things “which the eyes are capable of seeing.” In Holland especially this provided the intellectual basis for Reformed painting—and arguably for large portions of northern modernist painting in general.66

One of the most important effects of Calvin’s aesthetic program was that it relocated the religious and theological significance of art beyond the recognition of—or even association with—Christian subject matter. In most sectors of Protestantism the vast majority of the production, patronage and reception of art moved outside of the church—not outside of the practices of Christian theology but outside of ecclesial institutions as the primary spaces for doing visual theology. This involved a redefinition of the dichotomies between sacred and secular, such that a painting of “worldly” subjects might be thick with theological meaning concerning the presence and activity of God. It was for theological reasons that devout Protestant painters carefully depicted the created world, turning their attention toward the cosmos itself—in its sheer givenness—as the cathedral of God’s presence and the theater of God’s prodigious goodness and grace.

This was worked out with particular power in seventeenth-century Dutch painting, where a profound link was forged between observational naturalism and the theology of common grace. Observational still-life, portrait and landscape paintings came to be understood as religious paintings: (1) Still-life arrangements of fruit and flowers, for instance, were made and presented as potent meditations on temporality: all these good gifts of God are to be received with delight and thanksgiving (1 Tim 4:3-4), but those who covetously grasp after such things will be left with only decay. Ants, flies and even human skulls were often included to drive the point home. (2) Portraiture became radically inclusive, depicting peasants and laypersons of all social strata—i.e., those who couldn’t possibly afford or “merit” the expense of a painting—as treatises on the dignity of human persons (each made in the image of God) and as recognitions of the possibility that saints live among us unrecognized. (3) Dutch painters portrayed the surrounding landscape as a sphere of God’s grace, which shines through all things and gives all things their being. And within this sphere, portrayals of daily labor—herding livestock, planting, harvesting and domestic chores—became meditations on the biblical human vocation to care for and cultivate the earth. In short, seventeenth-century Dutch artists realigned all the traditional “machinery” of painting toward subject matter traditionally considered “low” and “profane,” producing paintings that (at the time) were fairly radical theological statements about the inherent dignity of everyday life and the comprehensive goodness of the creaturely things “which the eyes are capable of seeing.” The radicality of these paintings has long since become diffused and sentimentalized—and almost entirely undercut by photography and commercial advertising—but recovering some sense of it is crucial to understanding the course of northern modernism, including the ways that it eventually grappled with photography and advertising (see chapter seven).

The northern romantic tradition that Rosenblum traced is deeply rooted in a Calvinist theological aesthetic, which after the sixteenth century became increasingly influential in these Lutheran regions.67 Similarly to Calvin, Martin Luther argued that “the house of God means where he dwells, and He dwells where his Word is, whether it be in the fields, or in the churches, or on the sea.”68 In the deepest sense this Word is everywhere, donating and upholding the being of all things, but Luther emphasizes another sense in which the Word (the gospel) dwells in those who have the sensitivity to hear—or to feel—its reverberations. The Word is present in the fields, the churches and the sea, but it dwells in those creatures who experience it. Friedrich (and many of his romantic peers) thus submitted Calvinist aesthetics to a Pietist Lutheran modification: “The painter should not paint merely what he sees in front of him but also what he sees within him. If he sees nothing within himself, however, then he should refrain from painting what he sees in front of him.”69 For Friedrich this seeing “within” is not simply an interiority or a preoccupation with oneself; it is a conscious attunement to one’s intuitive sense of and longing for God and one’s intuitive sense of and longing for a just and right form of life.70 As we will see in what follows, the Protestant roots of this double sensitivity deeply shaped the theological grain of northern modernism, manifested in (1) its consistent preoccupation with the givenness of the world and (2) its strong eschatological longing for the world to be set right.

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) surely belongs in the previous chapter on French modernism (his most prolific and important years of painting were in France, and many of his strongest influences included French artists and writers), but the context of this chapter also demands a discussion of his work, which remained deeply rooted—both aesthetically and theologically—in the soil of northern romantic Protestantism. His painting career was brief, lasting only from 1880 to 1890, but it provides a clear and profound example of what this tradition looked like as it encountered the kinds of crises of faith experienced among Protestant Christians in the late nineteenth century.71

Van Gogh was raised in a devout Arminian Dutch Reformed home, and as he studied for entrance to seminary in Amsterdam, he encountered the strongest Dutch examples of modernist theology and higher biblical criticism.72 But as Debora Silverman points out, the Dutch modernism that influenced van Gogh was unlike the French modernism that influenced Baudelaire and Manet: liberal Dutch theologians generally prioritized the preservation of Christian piety, avoiding pantheism on the one hand and atheism on the other, opting instead for “a Schleiermachian posture of dependence on God and Christ rather than radical independence.”73

Van Gogh’s short stint at seminary and his subsequent efforts in ministry were difficult; he left disoriented and embittered, and he shifted to painting as his primary arena for theological wrestling. In December 1883, after moving back in with his parents in the Dutch town of Nuenen (after some difficult and disorienting years), van Gogh turned his artistic attention toward an old bell tower that stood in the center of the town’s main cemetery—the last remnant of a twelfth-century Catholic church that once stood on the site. Long after the tower had been stripped of its church, the churchyard continued to function as a burial ground for local peasants. Van Gogh depicted this site repeatedly over the course of more than sixteen months,74 preoccupied with its symbolic weight: The heavy block tower stands in the center of the graveyard with its steep pyramidal steeple pointing upward into the sky, enduring the passing of seasons (and the passing of human lives) with an ancient fortitude. Traditionally, bell towers signify a proclamation of hope—their ringing calls out to the corners of the earth, announcing salvation for all people and calling them into the body of Christ—and yet this tower struck the artist as an image of that hope waning to the point of crisis.

In the Parsonage Garden in Nuenen (1885), for example, van Gogh positions the viewer to look out over the family’s dormant, leafless garden, which lies under a thin layer of ice and snow. All the orthogonal lines in this cold landscape (formed by the low interior walls of the garden) point toward the old cemetery tower that stands on the distant horizon. The remains of innumerable dead bodies lie in the soil surrounding that distant tower; from this point of view it becomes a dark beacon against the setting sun, a threatening question mark at the center of the painting. And the question seems clear enough: can that old faltering ruin and the Christian hope that it represented possibly bear the weight of our suffering-unto-death—especially in the age of modernity? Indeed, this tower was “a stone ghost that would always haunt his horizons”75 with the cruel suggestion that an eschatological spring might never appear beyond the terrible winter of creaturely death.

On the evening of March 26, 1885, Vincent’s father, Theodorus van Gogh, died suddenly, suffering a massive stroke in the doorway of the parsonage. The funeral occurred on March 30 (Vincent’s thirty-second birthday), and the body was buried in the Protestant section of that cemetery. By this time the old tower had been scheduled for demolition, which was carried out in the months following the reverend’s death. By late May 1885 the wooden steeple had been dismantled (the rest would be torn down in June), and Vincent returned to paint the tower in this ruined state, creating his most haunting image of it: The Old Cemetery Tower in Nuenen (The Peasants’ Churchyard) (1885) (fig. 4.2). The dilapidated brick structure stands open to the sky without any of the upward proclamation of a steeple—an absence emphasized by the tight cropping near the top of the tower. The sky is heavy with clouds, and a handful of black crows circles overhead. Spring has come to the Dutch countryside—flowers of various colors blossom around the tower’s base—and yet the Christian hope of resurrection that the tower symbolizes seems as distant as ever: the new flowers grow among cruciform grave markers, which stand facing the ruinous bell tower in ever-deferred expectation.76 As David Hempton puts it, this painting presents us with “a relic of Christendom, the remaining stump of a culture in which church and people were indissolubly linked together in life and death. [But] even the stump was crumbling.”77 In fact this echoes van Gogh’s own words about the painting:

I wanted to say how this ruin shows that for centuries the peasants have been laid to rest there in the very fields that they grubbed up in life. . . . [These fields] make a last fine line against the horizon—like the horizon of a sea. And now this ruin says to me how a faith and religion moldered away, although it was solidly founded—how, though, the life and death of the peasants is and will always be the same, springing up and withering regularly like the grass and the flowers that grow there in that churchyard.78

Figure 4.2. Vincent van Gogh, The Old Cemetery Tower in Nuenen (The Peasants’ Churchyard), 1885

Van Gogh’s Tower pulls much of the same theological freight as Friedrich’s Abbey: it holds human death (visualized as a cemetery extending endlessly “like the horizon of a sea”) in close proximity to the historically fragile structures of religious ritual and doctrine (visualized as a ruined church building). The passing of human lives is thus coupled with and problematized by the passing of religious norms—the very norms that have for centuries been a vital source of meaning and hope in the face of death. By locating this image of religious breakdown specifically in a graveyard, van Gogh (like Friedrich) emphasizes the limits of what is humanly perceivable and manageable: ultimately our beliefs are fragile like our bodies.

Figure 4.3. Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889

Four years later, van Gogh was still grappling with these same themes in his famous Starry Night (1889) (fig. 4.3), which also hauntingly echoes Friedrich’s Abbey. At the bottom of the painting a small church appears in the distance, butted up against the central vertical axis of the composition. Lauren Soth has argued that van Gogh intentionally rendered this as a Protestant church, referencing his Dutch upbringing rather than his immediate French (Catholic) surroundings.79 In contrast to the buildings surrounding it, the church’s windows are darkened and vacant, while overhead the vast night sky throbs with (electromagnetic, psychological and/or spiritual) energy. The left half of the canvas is dominated by a cypress tree that is planted in the foreground and reaches upward as a massive mirror image of the tiny church, its verticality dwarfing that of the distant steeple. This dark cypress is a traditional memento mori symbol—in a work from the previous year van Gogh had painted a similar “completely black” tree, which he referred to as a “funereal cypress”80—and as such it subtly gathers the symbolic weight of cemetery imagery (vis-à-vis van Gogh’s Tower or Friedrich’s Abbey) into itself and reaches upward into the sky like a black flame. In every sense the structure of the church becomes visually overwhelmed by ciphers of death (the dark tree) and cosmic vastness (the windy, starry sky).81

In one sense all these paintings speak to the deterioration of institutional Christianity in European societies, but they do so while struggling to retain vital inner meanings of Christian faith—to recover whatever in it was “solidly founded.” Van Gogh sharply criticized religious institutional structures (including dogmatic structures), yet he also made it clear that paintings like The Starry Night arose from “having a tremendous need for, shall I say the word—for religion—so I go outside at night to paint the stars.”82 In a letter to his brother Theo from 1882, van Gogh commented on the religious feeling still evident in Holland and England during the Christmas and New Year season:

Leaving aside whether or not one agrees with the form, it’s something one respects if it’s sincere, and for my part I can fully share in it and even feel a need for it, at least in the sense that . . . I have a feeling of belief in something on high [quelque chose là-haut83] even if I don’t know exactly who or what will be there. I like what Victor Hugo said: religions pass, but God remains.84 And [Paul] Gavarni also said a fine thing: the point is to grasp what does not pass in what passes. One of the things that will not pass is the something on high and belief in God, even if the forms change, a change as necessary as the renewal of greenery in the spring.85

By this point in his life van Gogh had indeed distanced himself from the cultural forms of Christianity that he grew up with, yet he would persistently struggle to conceptualize that “something on high” that cannot pass away because it gives and sustains being itself.86 The whole realm of creaturely beings passes, but the sheer gratuitous giving of being itself does not. And it is the source of that giving that van Gogh refers to as God—the “I don’t know exactly who or what” that both wholly transcends and is immanently present in the giving of all things. It is in this sense that the aspiration “to grasp what does not pass in what passes” becomes deeply intelligible.87

The crucial point, however, is that van Gogh believed that artists only meaningfully attend to the “something on high” when they attend to the world as it presents itself—both in the sense of its givenness (that there is anything at all) and its intelligibility (that one has coherent consciousness of it). This (Reformed) way of thinking about transcendence drove van Gogh deeply into observation of the world, rather than away from it, and into his responsive constructions on canvas. Indeed, as Debora Silverman argues, van Gogh always retained a “visual Calvinism.”88 However, like Friedrich, van Gogh also clearly modified Calvin’s injunction to depict only those things “which the eyes are capable of seeing.” He wanted his work to somehow convey a deeper kind of meaning that inhered in the very capability of the eyes seeing: He wanted “to express the thought of a forehead through the radiance of a light tone on a dark background. To express hope through some star. The ardor of a living being through the rays of a setting sun. That’s certainly not trompe-l’oeil realism, but isn’t it something that really exists?”89

As with Friedrich’s landscapes, van Gogh’s point was not simply that there is an infinite depth (or height) to existence that transcends human experience but that all the concrete particularities of the world (and one’s consciousness of those particularities) are sustained within that infinite depth. Writing about the vastness of the farmlands of La Crau (a village southeast of Arles), van Gogh described a “very intense” experience of a “flat landscape in which there was nothing but . . . . . . . . . . the infinite . . . eternity.”90 In letters to both Theo and Émile Bernard in July 1888, he recounted that during this experience he was accompanied by a man who was a sailor: “I said to him: look, to me that’s as beautiful and infinite as the sea, he replied—and he knows it, the sea—I like that better than the sea because it’s just as infinite and yet you feel it’s inhabited.”91 Indeed, the overriding preoccupation of van Gogh’s painting is not simply the infinite but the inhabitable infinite.

In fact van Gogh regarded experiences of the infinite as actually profoundly intimate—a kind of intimacy fostered by the making of paintings. He believed that the greatest artworks disclose “something complete, a perfection, [which] makes the infinite tangible to us. And to enjoy such a thing is like coitus, the moment of the infinite.”92 Thus for van Gogh the infinite and the eternal are associated not only with an ever-receding Beyond (a timeless no-thing) but also with an intense—even erotic—tangibility and immediacy. The infinite gives this space and these things and these others.

The givenness of other people was in fact central to van Gogh’s theology. The closest he comes to defining the “something on high” is in a letter to Theo late in 1882, in which he argues that “one of the strongest pieces of evidence for the existence of ‘something on high’ in which Millet believed, namely in the existence of a God and an eternity, is the unutterably moving quality that there can be in the expression of an old man . . . something precious, something noble, that can’t be meant for the worms.”93 The possibility of seeing this transcendent “something” in others is ultimately “the only thing in painting that moves me deeply and that gives me a sense of the infinite. More than the rest.”94 In a widely quoted passage from one of his letters, he proclaims: “I’d like to paint men or women with that indefinable something [je ne sais quoi] of the eternal, of which the halo used to be the symbol, and which we [now] try to achieve through radiance itself, through the vibrancy of our colorations.”95 As he wrote these words he had in mind his portrait of Eugène Boch (The Poet) (1888), which he had just completed. In this painting, Boch stares at the viewer with an expression that is pensive and earnest, and the flesh tones in his face flicker with passages of oranges, greens, reds and aquas—an intense “vibrancy of colorations.” And as van Gogh saw it, this flickering of the eternal in his friend’s face called for a different kind of spatial context: “Instead of painting the dull wall of the mean room, I paint the infinite . . . a simple background of the richest, most intense blue I can prepare.”96 This is in fact one of van Gogh’s first attempts at painting a starry sky, which gathers around Boch’s head as a kind of halo. During this time van Gogh also made several portraits of his postman and friend Joseph-Étienne Roulin (1888–1889), who selflessly cared for Vincent following his acute mental breakdown just before Christmas 1888, in which he had mutilated his left ear. Van Gogh paints Roulin as if he were a modern saint, in whom he sees the je ne sais quoi of the eternal glimmering (fig. 4.4).

Figure 4.4. Vincent van Gogh, Joseph Étienne Roulin, 1888

In an earlier letter, van Gogh concisely drew together all these things, the inhabitable infinite in the face of others: “I consider it absolutely essential to believe in God in order to be able to love.”97 He insisted that belief in God has little to do with “all those petty sermons of the ministers and the arguments and Jesuitry of the prudish, the sanctimonious, the strait-laced, far from it.”98 Rather, he believed that there was a much deeper sense in which it was necessary to believe in God:

by that I mean feeling that there is a God, not a dead or stuffed God, but a living one who pushes us with irresistible force in the direction of “Love on.” That’s what I think. Proof of His presence—the reality of love. Proof of the reality of the feeling of that great power of love deep within us—the existence of God. Because there is a God there is love; because there is love there is a God [cf. 1 Jn 4:7-16]. Although this may seem like an argument that goes round in a circle, nevertheless it’s true, because “that circle” actually contains all things, and one can’t help, even if one wanted to, being in that circle oneself.99

Van Gogh’s entire artistic oeuvre might be understood as a meditation on the circumscription of all beings within that circle.

And yet at the same time he held this together (in continuity with his Reformed upbringing) with a deep sense of the tragic cruelty and suffering that invades life and against which the “love on” becomes an imperative. Van Gogh carried a tremendous weight of personal disappointment and doubt that corresponded to a hopeful longing that can only be regarded as eschatological in orientation:

It always seems to me that I’m a traveler who’s going somewhere and to a destination. . . . In fact, I know nothing about it, but precisely this feeling of not knowing makes the real life that we’re living at present comparable to a simple journey by train. You go fast, but you can’t distinguish any object very close up, and above all, you can’t see the locomotive.100

The Sower with Setting Sun (1888), to take one example, is almost overtly eschatological. The lower three quarters of the composition consist of a seemingly cold, richly blue-violet field that has been prepared for planting. A peasant farmer strides across the soil, flinging seeds from his bag across the tilled earth. This figure was directly modeled after Millet’s famous Sower (1850), but in contrast to Millet’s iconic centering and monumentalizing of this figure, van Gogh greatly reduces the sower’s prominence, placing his striding feet halfway up the composition walking away from the centerline rather than toward it (or simply being on it). A handful of crows follow after him, snatching up some of the seeds before they are able to take root. Of course this imagery directly calls to mind Jesus’s parable of the soils (Mk 4:3-20), which van Gogh was intimately familiar with from childhood. This newly planted field recedes into the distance until it suddenly butts up against “a field of short, ripe wheat”101 ready for harvest. Thus the spatial continuity between foreground and background actually includes a dramatic temporal fissure between them.

In the uppermost register of the painting a gigantic yellow sun appears on the vertical centerline of the composition, setting behind the ripe wheat. Heat and light radiate outward like spokes from this gigantic golden orb, filling the sky with yellow, orange and yellow-green energy. The biblical parable is thus set into eschatological relief: as the sower labors in the here-and-now foreground, our vision vaults beyond him toward the setting of the sun—the end of the age, the future “harvest” of all that has taken root and borne fruit. In the center of the foreground, directly opposite of (and corresponding to) the blazing sun, an orange path (visually rhyming the color of the sky) ushers us into the sower’s field. The visibility of this path (and its destination) is limited, obscured by the churned earth, but it appears to veer off toward a distant house set within (perhaps even beyond) the mature wheat. This house—presumably the farmer’s house—appears on the horizon, at the furthest limit of terrestrial vision.

In Arles the seasons for sowing would have been February or October, with the second and third weeks of June devoted to the harvest,102 which means that van Gogh made this painting exactly when harvest (not planting) was in full swing in Arles.103 In this context, depicting a sower is strongly teleological, anticipating the “fullness of time” in which the sower’s labor is rewarded. Indeed, van Gogh saw this painting as registering “yearnings for that infinite of which the Sower, [and] the sheaf, are the symbols.”104 These are alpha and omega symbols: the sower stands at the beginning of the planting process whereas the sheaf stands at the end. And it is evident that he thought about such images in overtly eschatological terms: he described his Reaper (1889), for instance, as having “the image of death in it, in this sense that humanity would be the wheat being reaped. So if you like it’s the opposite of [or counterpart to] that Sower I tried before. But in this death nothing sad, it takes place in broad daylight with a sun that floods everything with a light of fine gold.”105 Van Gogh’s yearnings were for a day in which all things, even death itself, would finally be flooded with light.

Though we do not have the space to develop it here, the work of Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863–1944) offers an important comparison, and the scholarship on his work would similarly benefit from greater attention to its theological roots and implications. The themes of the inhabitable infinite are explored throughout his oeuvre, including paintings like his thoroughly Friedrichian Summer Night at the Coast (c. 1902) and in his massive Sun (1911), the central panel of his frieze at the University of Oslo. Like van Gogh, Munch advanced an expressionist modification of Calvinist painting: “Nature is not only what is visible to the eye—it also shows the inner images of the soul—the images on the back side of the eyes.”106 He also similarly echoed the traditions of Protestant vanitas painting in his tense double affirmation that (1) an underlying goodness shines through all of creation and (2) in the face of this goodness, creaturely experience is marked by profound dysfunction and suffering. The question of whether Munch believed this suffering was redeemable is powerfully foregrounded in works such as The Scream (1893)107 and his remarkable Golgotha (1900).

And like van Gogh, Munch provides a potent example of a modernist struggling to retain an acutely fragilized faith. In 1934, toward the end of his life, Munch wrote in his notebook: “My declaration of faith: I bow down before something which, if you want, one might call God—the teaching of Christ seems to me the finest there is, and Christ himself is very godlike—if one can use that expression.”108 The simultaneous earnestness and brittleness of this confession of faith is emblematic of much modernist art within the northern tradition.

The theological concerns that preoccupied Friedrich and van Gogh are also clearly discernible in the work of the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian (1872–1944). Throughout the first two decades of his artistic career (roughly 1888 to 1910), Mondrian’s numerous landscape, still-life and portrait paintings exhibit a deep and direct indebtedness both to seventeenth-century Dutch Reformed painting109 and to German romanticism.110 Mondrian’s Oostzijdse Mill Along the River Gein by Moonlight (c. 1903) (fig. 4.5), for example, is strikingly Friedrichian: a luminous full moon (a recurrent motif in Mondrian’s paintings, especially in 1906–1908) presides over the surface of a marshy expanse, and the dark silhouette of a windmill looms on the horizon in the compositional position where we might expect Friedrich to have placed the ruined façade of Eldena Abbey.111

Mondrian grew up in a devout Dutch Calvinist home and learned to draw at an early age by making devotional lithographs with his father. When he entered the Academy of Fine Art in Amsterdam in 1892, he went to live (until 1895) in the home of Johan Adam Wormser, the publisher and close friend of the massively influential neo-Calvinist theologian and politician Abraham Kuyper.112 Throughout his time at the academy Mondrian was right in the midst of the most energetic neo-Calvinist thinking going on at the time. In 1893 he switched his church membership (surely against his father’s wishes) from the Dutch Reformed Church to the newly established Reformed (Gereformeerde) Church, which had been founded in 1892 under Kuyper’s leadership. Mondrian directed some of his artistic energies during this time toward Protestant commissions, including the semicircular painting Thy Word Is the Truth (1894)113 for the National Christian School in Winterswijk (where his father was the school principal), a series of twenty-eight lithographs of Protestant martyrs titled Joint Heirs of Christ (1896–1897) and panel designs for the hexagonal pulpit at the English Reformed Church in Amsterdam (1898).

Figure 4.5. Piet Mondrian, Oostzijdse Mill Along the River Gein by Moonlight, c. 1903

Around 1900 Mondrian experienced some sort of deep crisis of faith. He gradually withdrew from the Reformed community and turned to more esoteric forms of spirituality, particularly theosophy—a syncretic blending of Judeo-Christian mysticism, evolutionary science and a variety of Eastern spiritualities (especially Indian and Egyptian)—which had become popular in Europe around the turn of the century.114 In 1908 he attended a series of lectures by Rudolf Steiner, who was in Holland as part of a wide-ranging speaking tour,115 and in May 1909 Mondrian formally joined the Dutch chapter of the Theosophical Society.116 His theosophical beliefs are well documented and have been much discussed,117 but art historians have tended to frame them solely within a narrative of rupture from his Calvinist upbringing. These accounts often downplay (or wholly ignore) the extent to which Mondrian’s painting and writing also demonstrate significant continuities with his Reformed roots.

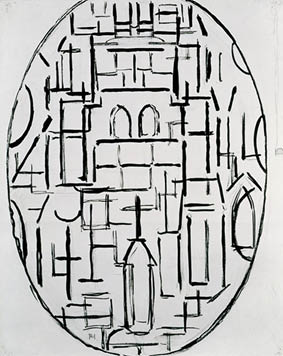

The most important years of development and transition in Mondrian’s work were 1912 to 1915, during which he methodically worked toward nonobjective abstraction. He moved to Paris in late 1911 or early 1912 (initially renting a room at the headquarters of the French Theosophical Society) and stayed until 1914 when he returned to the Netherlands to visit his ill father and quickly found himself immobilized by the outbreak of World War I. His exposure to Parisian cubism during those two years deeply impacted him, but he internalized its significance differently than did his French peers: he saw in cubism a new formal language for wrestling with the essentially theological questions that had preoccupied him. As he sought an increasingly “aesthetically purified”118 mode of painting during this period, the most recurrent pictorial subjects through which he focused his experimentations were seascapes and church façades—thoroughly Friedrichian motifs chosen specifically “to express vastness and extension.”119 In Mondrian’s theoaesthetic imagination, the most salient forms for alluding to the sacred remained the horizontality of the seemingly endless sea and the verticality of the church façade.

Figure 4.6. Piet Mondrian, Composition No. 10: Pier and Ocean, 1915

Over the course of several years he rigorously subjected these motifs to processes of geometric simplification. Paintings like Seascape at Sunset (1909) or Dune V (Dunes near Domburg) (c. 1909–1910)120 gave way to gridded abstractions of The Sea (1912), at least six versions of Pier and Ocean (1914), six versions of Ocean (1914–1915), and Composition No. 10: Pier and Ocean (1915) (fig. 4.6). Similarly, Mondrian’s Church Tower near Domburg (1910–1911) was transformed into the increasingly abstract Church at Domburg (1914), Composition with Color Planes: Façade (1914), two versions of Composition in Oval with Color Planes (1914) and at least seven versions of Church Façade (1914–1915) (fig. 4.7). Carel Blotkamp interprets this preoccupation with abstracted church façades as Mondrian displacing (and replacing) the religious edifices of his childhood: these “dying houses will be replaced by new ones.”121 Indeed, in the earlier façade paintings (1910–1911) there are especially strong echoes of Friedrich’s and van Gogh’s scrutinizing of the old edifices of the church, but they never appear in ruined form (as they do in Friedrich and van Gogh), and it is unclear that we are justified in interpreting the geometricizing of the façades in terms of either obliteration or replacement. By his own account, Mondrian chose the theme of the church façade to express the “idea of ascending.”122 Is his treatment of this idea a repudiation of the church he was raised in or an attempt to find something deeper within it (as it was for Friedrich and van Gogh)?

Figure 4.7. Piet Mondrian, Church Façade 1: Church at Domburg, 1914

For Mondrian the process of “abstracting” was not destructive of the things represented; rather, it was a means of clarifying the “mutual relations that are inherent in things”123—the fundamental interrelatedness that provides structure and meaning in the world. As he saw it, the core deficiency in traditional Dutch painting (and European painting in general) was that the most fundamental relations become “veiled” in “descriptive” naturalistic representations.124 The problem is not that figurative paintings are illusionistic but that they divert too much attention away from the meaningfulness of spatial (and ontic) relations per se. They give us too much information, immediately launching us into thinking about bowls of fruit, the dangers of sailing, the desire for loving companionship, Napoleonic politics and so on—any number of things other than the meaningful “pure plastics” of the painted surface itself.

Rather than reproducing natural appearances, Mondrian believed that modern painters should devote themselves to identifying and distilling the most basic relations of color and shape, within which all other visual forms become thinkable as possibilities. Specifically, he believed that painting becomes more “aesthetically purified” when (1) naturalistic color is pushed toward the primary colors from which all colors are derived and (2) naturalistic lines are pushed toward the horizontal and vertical geometric axes between which all other lines might be conceived.125 In one of his most widely quoted passages, he argues that “in nature all relations are dominated by a single primordial relation, which is defined . . . by means of the two positions which form the right angle. This positional relation is the most balanced of all, since it expresses in a perfect harmony the relation between two extremes, and contains all other relations.”126 And he thought that this relation must be expressed in straight lines, “because all curvature resolves into the straight [line].”127 For Mondrian, the kind of painting that traffics in the most primordial spatial relation—that which in fact implies and “contains all other relations”—is one that manages horizontality (parallel to the surface of the earth) in relation to verticality (perpendicular to the surface of the earth).128 Indeed, he believed that managing a painting in this way was a means of figuring “the immutable” insofar as it achieved a kind of iconic “plastic expression of immutable relationship: the relationship of two straight lines perpendicular to each other.”129 By this rationale he came to regard his grid-based geometric abstractions as attempting “a pure reflection of life in its deepest essence”—not by way of picturing anything but by iconizing, or even instantiating, the unalterable simple relation that contains all other relations.130 His paintings increasingly simplified into asymmetrical grids of primary color: iconic figurations of the immutable ground of being from which all concrete, mutable existence is given (see fig. 4.8).

Figure 4.8. Piet Mondrian, Composition, 1921

This line of thinking wasn’t well received by Hans Rookmaaker, who was suspicious of the theological implications that might be at work here. He recognized that “Mondrian drew upon a truly profound outlook on life and upon philosophical principles,”131 and even that the paintings that he derived from these principles were “exceptionally lovely.”132 Yet he also believed that Mondrian’s total withholding of representation meant that these paintings were either obdurately mute133 or escapist, insofar as they “endeavored to construct an intellectual and abstract fortress of transcendental beauty beyond this world.”134 And with time Rookmaaker’s view of this work became increasingly sour. As he saw it, Mondrian and his colleagues in both Dutch De Stijl and the German Bauhaus had been “building a beautiful fortress for spiritual humanity, very rational, very formal: but they did so on the very edge of a deep, deep abyss, one into which they did not dare to look. For them fear, agony, despair, and absurdity were the real realities.”135

Mondrian would not have recognized his work in Rookmaaker’s assessments of it. For Mondrian, abstract painting was not escapist: his concern was not to avoid or repudiate natural appearances but to intensify our perception of them. He believed that there is a profound sacredness to the world as we perceive it: “Nature is that great manifestation through which our deepest being is revealed and assumes concrete appearance.”136 However, he also became increasingly convinced that nature’s disclosure of “our deepest being” is “far stronger and much more beautiful than any imitation of it can ever be,” and thus “precisely for the sake of nature, of reality, we avoid [imitating] its natural appearance.”137 His decision to abandon the representation of nature (vis-à-vis his training as a Dutch realist painter) cannot be taken as indicating that he had “shunned reality,” as Rookmaaker thought;138 it only indicates that he had shunned pictorial imitations of natural appearances. As with Friedrich and van Gogh, Mondrian echoes Calvin’s theology of art in his orientation toward the goodness of the world: “To love things in reality is to love them profoundly; it is to see them as a microcosmos in the macrocosmos.” But one also hears in Mondrian’s reasoning strong echoes of Calvin’s iconoclastic argument: “Precisely on account of its profound love for things, nonfigurative art does not aim at rendering them in their particular appearance.”139 Interestingly, he has extended the reach of Calvin’s iconoclasm from religious to natural subject matter.

Directly analogous to the neo-Calvinist Abraham Kuyper,140 Mondrian did not believe that this refusal undermined painting as much as it freed it and redirected it toward other more vital tasks: a more chastened investigation of reality from within the mechanics of painting itself. Indeed, Mondrian’s theory of art could have found its grounding entirely in Kuyper’s neo-Calvinism. As Kuyper wrote in his 1898 Stone Lectures:

Art reveals ordinances of creation which neither science, nor politics, nor religious life, nor even revelation can bring to light. She is a plant that grows and blossoms upon her own root, and without denying that this plant may have required the help of a temporary support, and that in early times the Church lent this prop in a very excellent way, yet the Calvinistic principle demanded that this plant of earth should at length acquire strength to stand alone and vigorously to extend its branches in every direction. . . . Art, like Science, cannot afford to tarry at her origin, but must ever develop herself more richly, at the same time purging herself of whatsoever had been falsely intermingled with the earlier plant. Only, the law of her growth and life, when once discovered, must remain the fundamental law of art for ever; a law, not imposed upon her from without, but sprung from her own nature. And so, by loosening every unnatural tie, and cleaving to every tie that is natural, art must find the inward strength required for the maintenance of her liberty.141

Whether he realized it or not, Kuyper had thus laid out a powerful neo-Calvinist argument for formalist abstract painting—an argument that would find its most potent realization in Mondrian’s paintings.142

The important point here is that Mondrian’s grids are profoundly intelligible from within a Protestant theological framework. They were in many respects meant as theological manifestoes, oriented as visual articulations of the “vastness,” “the immutable” and the “real” within which all concrete experience unfolds. Mondrian came to regard his works as “Abstract-Real painting” insofar as each of these paintings is “a composition of rectangular color planes that expresses the most profound reality . . . by plastic expression of relationships and not by natural appearance.”143 Historian Peter Gay was alert to the theology in play here, arguing that Mondrian “never ceased wrestling with his father’s rigorous Calvinism, which he at once rejected and incorporated,” reconfiguring it into a kind of “secular religiosity” in which his painting became “a form of prayer.”144 That seems right, though it is unclear why (or in what sense) we should regard Mondrian’s religiosity as “secular.” Susanne Deicher’s summary of Mondrian’s thinking is more modest, claiming that his writings “were essentially theological, even though the name of God no longer appeared.”145

And they were not only theological; all of this had a subtle but sharp sociopolitical edge to it. Mondrian believed that “equilibrated relationships in society signify what is just,” and thereby “one realizes that in art too the demands of life press forward” toward equilibrated relationships.146 In other words, he saw aesthetics and ethics as deeply linked: the artistic interrogation and balancing of formal aesthetic relationships is intrinsically dependent upon—and elicits questions about—the bases by which we make judgments about the rightness and justness of social relationships. According to Mondrian, “the New Plastic brings its relationships into aesthetic equilibrium and thereby expresses the new harmony” that we yearn for in all spheres of life.147 Blotkamp glosses it this way: Mondrian’s reduction of painting to “essential contrasts between horizontal and vertical and between the three primary colors, were supposed to express the unity that was the final destination of all beings, the unity that would resolve harmoniously all antitheses.”148 In this sense Mondrian’s abstract panels are emblems of eschatological desire, many of them made in the midst and wake of the profoundly devastating First World War. For all of their austerity and cerebral calculation, they are full of longing for the world to finally be set right.149

Striking comparisons might be drawn to the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) if we had the space. Like Mondrian, she was deeply interested in theosophy, particularly in the esoteric Christian writings of Rudolf Steiner.150 Following Steiner, Hilma af Klint believed that painting was a powerful means of materializing the spiritual, though unlike Steiner she came to believe that improvisational, even mediumistic, abstract painting was the purest means of achieving this. Throughout the 1890s she had made impressionistic landscape paintings and beautifully delicate floral studies, but by 1906 (several years before Mondrian or anyone else) she had pushed into totally abstract painting. Some of these were massively large, such as The Ten Largest (1907), which depicted the four spiritual ages of humankind. Over the course of several years she produced a series of 193 works that she referred to as The Paintings for the Temple, intuitively exploring the structure of spiritual realities through geometric and curvilinear forms. Particularly beginning in 1912 (roughly coinciding with Steiner’s founding of the Anthroposophical Society), her work became pervaded by Judeo-Christian imagery: Adam and Eve, crosses, the crucifixion, the Tree of Life and Tree of Knowledge, the dove of the Holy Spirit and so on. The scholarship on Hilma af Klint has rapidly expanded in the past decade, but there is much more work yet to be done on the theological impulses and implications of her work.

Within the northern modernist discourse on spirituality and art, Vasily Kandinsky (1866–1944) was enormously influential. This influence was due not only to the force and content of his painting practice but also to his charisma and erudition in both speech and writing. In the words of his friend and colleague Paul Klee, Kandinsky was a man with “an exceptionally fine, clear mind” who along with his paintings “also tries to act by means of the word.”151 He was a charismatic teacher, and he published numerous statements of his philosophies of art throughout his lifetime, the most influential of which was his 1911 book On the Spiritual in Art.152