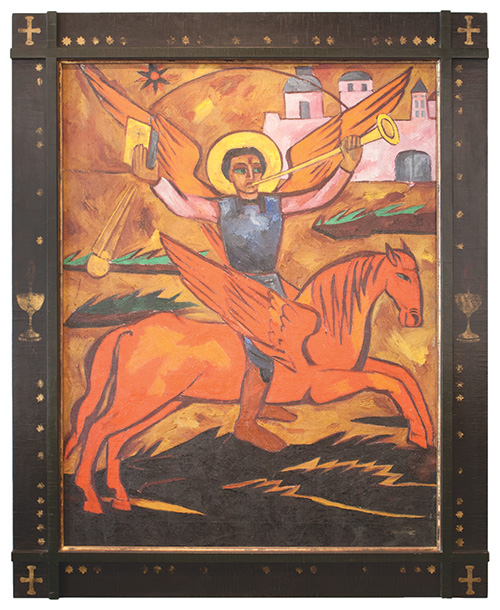

Plate 5. Natalia Goncharova, Saint Michael the Archangel, 1910

Great artists have their own ways of plunging headlong into their doubts, the better to overcome them. Like Plato’s pharmakon, their work is both the poison and the antidote.

Thierry de Duve1

How can we give the word back its force? By identifying with the word more and more closely. . . . To understand cubism, perhaps we have to read the Early Fathers.

Hugo Ball2

Although Vasily Kandinsky made his most significant work in Germany (see previous chapter), he always maintained that the true coordinates of his artistic imagination were thoroughly Russian. Indeed, he referred to his native Moscow as his “spiritual tuning fork.”3 The character of this spiritual attunement included many dimensions of Muscovite culture, but it was particularly informed by Russian Orthodox Christianity. In his 1913 “Reminiscences” Kandinsky identified the most formative experiences that propelled him as a painter—particular exhibitions, concerts, scientific lectures and early drawing lessons—almost all of which occurred in Russia. Among these he also included his encounters with the great wooden houses in the Russian province of Vologda, where he traveled in 1889 as an ethnography student. Amidst the brightly colored ornamentation that filled the interiors of these houses, Kandinsky described the powerful effect of the rooms as making him feel as if he were “surrounded on all sides by painting, into which I had thus penetrated.” He claimed that these rooms gave him a sense of what it would mean “to move within the picture, to live in the picture,” and thereafter he specifically associated this sense with worship spaces: “the same feeling sprang to life inside me with total clarity” on several subsequent occasions in Orthodox and Catholic churches and chapels.4

In his descriptions of the Vologda houses, he made special note of the traditional Orthodox “beautiful corner” or “red corner” (krásnyi ugol).5 Each wall leading into this corner was usually covered with icons and printed pictures of saints, but the highest position in the corner, where the two walls and ceiling meet, was reserved for the most important icon: either the Holy Face of Christ or the icon of Virgin Hodegetria holding and pointing toward the incarnate Christ child (hodegetria means “she who shows the way”). Such corners were illuminated by small red pendant lamps, which Kandinsky evocatively described as “glowing and blowing like a knowing, discretely murmuring, modest, and triumphant star.” The overall effect on him was profound: “It was probably through these impressions, rather than in any other way, that my further wishes and aims as regards my own art formed themselves in me.”6

Kandinsky was not the only Russian modernist deeply affected by the visual culture of Russian Orthodoxy. The manifold religious artifacts and practices—including holy icons, sacred architecture, Easter processionals, liturgical vestments, religious folk art, popular religious prints (lubki) and so on—provided much of the visual grammar and conceptual framework for the development of modernism in Russia. From the 1880s into the 1930s, there was an especially strong resurgence of interest in Old Russian icons, many of which were being cleaned of centuries of soot and varnish, restored to their original vibrancy and placed on public display.7 These exerted a powerful influence on young modernists: under the cross-pressures of the modern age, the icon began to function as “a modernist prism for seeing the world anew.”8 And this function was not “merely aesthetic” (if such a designation is even possible); Orthodox visual theology had deeply shaped the visual imaginations of Russian avant-garde artists—most of whom were raised in the Orthodox faith. In fact, as John Bowlt has pointed out, a significant number of these artists began their careers as icon painters and seminarians.9

Nor was this influence simply a matter of generic enculturation: the most innovative years in the development of Russian modernism coincided with an enormous amount of religious and theological energy in Russian culture. As with much of the rest of Europe, Russia experienced a significant spiritual revival in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Philosophical theology flourished in the universities in the 1890s, and it remained a vital and influential discourse until it was repressed by the Soviets. Particularly in the decade between the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) and the beginning of the First World War (1914–1918), artistic modernism thrived alongside a swell of spiritual and religious activity, both inside and outside of the Russian Orthodox Church.10 Writing in 1910, Aleksandr Mantel reported on the extent to which Moscow’s “auditoria were filled with people listening to lectures on god-seeking.”11 And in the course of this widespread and multifarious spiritual searching, artists often employed the visual grammar that was most sacred to them, even if they felt that it had to be adapted to a modern context. According to Bowlt, “far from renouncing the methods of icon painting, church frescoes, and ceremonies, the [Russian] avant-garde reprocessed and transmuted them, and direct references to these disciplines can be found in their major pictorial achievements.”12

This chapter will press into this claim, exploring the theological implications of this kind of reprocessing, transmuting and referencing. As we turn our attention further north and further east, we will investigate some of the most influential examples of modernism as it developed in Russia,13 and then we will loop back around to Germany and Switzerland to look at some similar developments springing from the roots of the Dada movement in Zurich.

Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962) was arguably the most important Russian avant-gardist until her initial departure from Russia in the spring of 1914 (and then her permanent departure in 1915). She believed that the primary insights of modernism belonged to its neoprimitivism: its turning toward “primitive” artistic cultures as a means of resisting the dehumanizing aspects of modernity’s materialism. She was interested in any and all premodern (or nonmodern) artistic traditions, but she came to believe that the deepest resources resided within her own country and its cultural histories. As Alain Besançon summarizes: “In the West, the primitive was somewhere else [in the world]. In Russia, it was within. [Primitivism] did not take you away from the fatherland, it rooted you in it.”14 In particular, Goncharova began to identify the most desirable aspects of the “primitive” with the aesthetics—and aesthetic theologies—of Eastern Orthodoxy: medieval icons and religious folk art were of especially vital importance.

Goncharova was born in the province of Tula into an aristocratic family with strong ties to the Orthodox Church. Her maternal grandfather was a professor of theology at the Moscow Theological Academy, and a number of relatives on that side of the family were priests.15 She attended church throughout her youth and became versed in Christian theology, and in fact it seems that she remained a religious person throughout her life.

Her artistic career was attended by controversy from early on,16 most of which revolved around her handling of Christian subject matter. Especially between 1910 and 1912 Goncharova painted numerous religious images in a flattened, roughly hewn visual vernacular,17 many of which were derived directly from well-known icons.18 Saint Michael the Archangel (1910) (plate 5), for example, closely follows the Russian iconic tradition, wherein the angelic archistrategus is often depicted riding a blazing red-winged horse over a dark abyss, trampling the demonic dragon. Goncharova’s version of the icon closely adheres to the tradition, presenting a sober-minded, even haunting image of eschatological victory over evil: crowned with a rainbow (Rev 10:1), Saint Michael carries a smoking censer (Rev 8:3-5), holds the Word aloft (Rev 14:6) and inaugurates the apocalyptic judgment of the earth with a blaring trumpet blast (Rev 8:7–9:14). But Goncharova’s painting transposes the icon tradition into modernist form: with highly saturated and coarsely painted oil on canvas, the figuration borrows simultaneously from the stiff, flattened figuration of Russian lubki (popular religious prints) and the materiality of French modernist painting (which she had seen in the extraordinary collections of Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov, and in the massive 1908 salon of The Golden Fleece). The major questions and controversies about this kind of work (which we will discuss further in a moment) gathered especially around this disarming presentation of traditional religious motifs in “crude” painterly form.

Plate 5. Natalia Goncharova, Saint Michael the Archangel, 1910

Others of her religious paintings deviated further from the iconic tradition.19 The large painting of the Elder with Seven Stars (Apocalypse) (1910), for example, seems to have no discernible precedent in the icon tradition, though it is a careful handling of the vision of Christ in Revelation 1:12-20: a dark-skinned Son of Man appears amidst a seven-branched lampstand, holding seven stars in his right hand. Goncharova’s draftsmanship is deliberately clunky, and the coloration crudely collapses the volume of the forms; but it is easy to agree with Andrew Spira that “there is nothing satirical or patronizing” about her religious paintings.20 And many of her contemporaries agreed: after seeing several of them in 1911, the critic Sergei Gorodetsky admitted that he was deeply moved by Goncharova’s “profound religious compositions.”21

Other critics, however, received Goncharova’s religious works as blasphemous. The objections spanned a range of issues: In the Orthodox Church the holy vocation of iconography (icon writing) was a sacred duty reserved for (male) monastic scholars and intended for sacred use. The very incidence of a nonordained woman painting these subjects in large oils on canvas for public exhibition inevitably raised questions of irreverence. In an open letter addressed to female readers, Goncharova defended her work—and did so primarily on theological grounds:

To repeat all of the good and idiotic things that have been said about my sisters a thousand times already is infinitely boring and useless, so I want to say a few words not about them, but to them: Believe in yourself more, in your strengths and rights before mankind and God, believe that everybody, including women, has an intellect in the form and image of God.22

Certainly the most provocative place to assert and test this was in the depiction of holy imagery.

The larger issue, however, had less to do with who she was or what she was depicting than with how she handled these sacred subjects. The deliberately imprecise paint handling struck many viewers as disrespectful. She disagreed, arguing that her work simply acknowledged a deeper diversity within the icon tradition than these viewers were recognizing: “People say that the look of my icons is not that of the ancient icons. But which ancient icons? Russian, Byzantine, Ukrainian, Georgian? Icons of the first centuries, or of more recent times after Peter the Great? Every nation, every age, has a different style.”23 And indeed the pressures of her own age must be worked through yet a different style. Goncharova believed that artists concerned with preserving ancient values must perpetually renegotiate the most fitting “form” for embodying those commitments within present cultural contexts:

I maintain that religious art and art that exalts the state [gosudarstvo] was and will always be the most majestic and complete art, in large part because such art is, above all, not theoretical but traditional. . . . This means that [the artist’s] thought is always clear and definite; the artist has only to create for it the most contemporary and most definitive form.24

This contemporizing of form was not meant to empty these (religious) subjects of their (theological) content; to the contrary, Goncharova believed that “during all eras, the subject depicted was and will be important—as important as how it is depicted”—but she also believed that the form of depiction continually needs to be revisited for the ongoing health of the subject.25

In fact, Goncharova appears to have thought seriously about the religious subject matter of her work. In personal notes from about 1911 she described an idea for painting a “church mural motif” depicting a garden of trees tended by birds, saints and angels: “A radiant Christ, a pole axe in his hand, descends from a mountain to his church and garden in order to find his withered tree.”26 This is arresting imagery, synthesizing several loaded biblical references into a vision of Christ judging the unfaithfulness of the church.27 The implications are simultaneously pietistic (calling for repentance) and polemical (accusing the church of being as spiritually dead as the temple—symbolized as a withered tree—that Jesus judged in Mk 11). Given these sharp polemics, Goncharova questioned herself: “Will the Lord not let me paint this? Lord forgive me. . . . Others argue—and argue with me—that I have no right to paint icons. I believe in the Lord firmly enough. Who knows who believes and how? I’m learning how to fast.”28

In December 1910 Goncharova and her partner Mikhail Larionov29 launched the avant-gardist group Knave of Diamonds (Bubnovyi Valet)30 with an exhibition of thirty-nine artists, including artists working not only in Russia (e.g., Alexandra Exter and Kazimir Malevich) but also in France and Germany (Gleizes, Kandinsky, Münter and Jawlensky). Goncharova was quickly dubbed the “Queen of Diamonds” in the Moscow press,31 and her apocalyptic inflections were attributed to the group as a whole. She designed the cover for the exhibition almanac, featuring a sword-wielding archangel on horseback—a design that directly prefigured Kandinsky’s placement of Saint George on the cover of the Blue Rider Almanac (1912). In fact Kandinsky was quite taken with Goncharova’s work: he published her apocalyptic drawing of The Vintage of God (1911–1912) in that Almanac and curated her work into the second Blue Rider exhibition.32 The two became friends at the Knave exhibition in Moscow and found that they held similar convictions both about the evils of modern materialism and about the role of art in generating spiritual and social renewal.

Goncharova regarded Western modernism (primarily French cubism and Italian futurism) as bearing valuable social and spiritual meanings, but she also grew wary of it, fearing that it was smuggling problematic European philosophical values into Russian society and thus obscuring its own unique spiritual resources. By 1913 she proclaimed:

I have studied all that the West could give me, but in fact my country has [already] created everything that derives from the West. Now I shake the dust from my feet [alluding to Mt 10:14] and leave the West. . . . My path is toward the source of all arts, the East. . . . At the present time Moscow is the most important center of painting.33

Arguing that the Russian “avant-garde” had become too preoccupied with (and deferential to) France, Goncharova and Larionov abandoned Knave and organized the Donkey’s Tail,34 touting a modernism that “derives exclusively from Russian traditions and does not invite even a single foreign artist.”35 As they saw it, modernists could find no better models for a robust Russian spirituality (and a hedge against western European materialism) than in Orthodox icons and folk art: “out of respect for ancient national art” they devoted a large portion of their group exhibition to collections of old icons and popular prints.36

Goncharova’s work dominated the Donkey’s Tail exhibition (held in Moscow in the spring 1912), showing fifty-four paintings in the first hall of the gallery. At least eight of these paintings depicted religious subjects, the most prominent of which was the large Evangelists (1910–1911), a four-panel painting derived from images of saints standing on either side of the central icon of Christ in a traditional Orthodox iconostasis. The presentation of this subject matter was not intended to be sarcastic, but the stark expressionist coloration and mark-making struck many viewers as irreverent. The imagery also inexplicably deviated from traditional iconography: the evangelists are depicted with gray beards and holding scrolls, two attributes conventionally reserved for Old Testament prophets—perhaps implying that the Gospels had themselves become an “old” testament. And without any further context provided, the message of these evangelists—the referent to which they point—was uncomfortably absent, and thus open ended. The two evangelists on either side turn toward the empty space between the central panels, where an Orthodox believer would expect to see the holy image of Christ. Ultimately the tipping point was the title of the exhibition: the public censor deemed it blasphemous to include paintings of holy subject matter in an exhibition that was so irreverently titled. The police were ordered to remove all of her religious paintings, including the Evangelists, from the exhibition under the accusation of “anti-religious blasphemy.”37

By 1913 Goncharova had become the most visible and influential modernist painter in Russia. She was featured in the first full-scale retrospective of an avant-gardist in Moscow, which was also the first major exhibition of a female artist.38 Sponsored by one of Moscow’s most important art dealers, Klavdiya Mikhailova (also a woman), the huge exhibition contained 768 works—nearly everything Goncharova had made from 1903 to 1913—and it was accompanied by a published catalog. The show received massive attention: according to one contemporary critic Goncharova became an “overnight sensation.”39 And yet the religious works continued to ignite controversy. This was especially the case in the spring of 1914 when Goncharova presented a smaller version of this show (249 works) in Saint Petersburg in a major solo exhibition at Natalia Dobychina’s Art Bureau, the foremost private art gallery in Russia. All the religious paintings exhibited in this show (as many as twenty-two in total) were once again physically removed by the police on the grounds of blasphemy. One particularly offended reviewer railed against Goncharova’s “outrageous and repulsive” treatment of the sacred motifs. The Evangelists once again drew particular scorn: “the height of outrage are four narrow canvases depicting some kind of monsters labeled in the catalogue as no. 247 ‘The Evangelists.’ . . . [This] premeditated deformation of holy persons must not be allowed.”40 However, when the local spiritual censor examined the works following their removal, he overruled the critic’s accusations: “finding no blasphemy in them but in fact all the signs of an appropriate style, he allowed the pictures to be hung back up.”41

With the outbreak of World War I, Goncharova almost immediately published the Mystical Images of War (1914), a series of fourteen lithographic prints that commingled imagery of human and angelic warfare. The cover depicts the Angel of the Lord with an uplifted sword in his/her right hand, and the interior prints unfold through a series of harsh apocalyptic images: Saint George drives a spear into the mouth of the demonic dragon; Angels and Airplanes engage in aerial combat; angels drop boulders on The Doomed City; Death rides The Pale Horse over skeletal human remains; the nude Whore of Babylon (Woman on the Beast) raises a goblet as she rides a two-headed monster over a field of broken bodies; Saint Michael the Archistrategus gallops on horseback over a burning landscape; an archangel soberly presides over A Mass Grave; a group of soldiers encounters the Mother and Christ Child in a Vision in the Clouds; and so on. The series anticipated the brutalities of modern warfare that would rage in Europe over the next few years, but it did so while casting them specifically into spiritual light.

As evidenced by the controversies surrounding her work, the theological implications of Goncharova’s religious paintings remain undecidable. Religious (particularly apocalyptic) subjects were central to her modernism—they provided the site for her to think through the meanings of human life and human history—but in taking up these subjects she felt that she had to twist them out of the grip of convention. For Goncharova, Christian spirituality in a modern age demanded a jolting of one’s expectations and an unsettling of conventional religious images just enough to put them in play once again—a task for which modernist painting proved to be quite proficient. It is this jolting, this unsettling that generates much of what is most controversial and most theologically important about modern art.

Similar dynamics demand further consideration in the work of numerous other artists raised in Russia and eastern Europe, for whom we have no space to explore. The controversial works of the Russian symbolist Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin (1878–1939), for example, include paintings of The Mother of God of Tenderness Toward Evil Hearts (1914–1915), a haunting modernist icon painted specifically for the moment of Europe’s descent into world war, as well as Our Lady of Petrograd (1920), which was painted during the extremely turbulent years of the Russian Civil War (1918–1921). Alexei von Jawlensky’s (1864–1941) numerous versions of the Mystical Head (late 1910s), Savior’s Face (early 1920s) and Meditations (1930s) were overtly intended as modern icons.42 The pivotal work in the career of the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi (1876–1957) was his sculpture of The Prayer (1907), a kneeling woman mourning at a gravesite. And following from this work, Brancusi’s numerous Heads (1910s–1920s) are, as Spira notes, “surely influenced by the heads of saints,” particularly those decapitated martyrs that appear in church frescoes throughout his native Moldavia.43

Andrew Spira argues that “of all the explicit references to Christian imagery in the art of the Russian avant-garde, surely the most radical and profound was the Suprematist work of Kazimir Malevich. . . . [His work passed] beyond a mere similarity to icons towards a total identification with them.”44 The most salient example of what he has in mind is Malevich’s contributions to The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0.10 (Zero-Ten), which was shown in December 1915 to January 1916 at Natalia Dobychina’s gallery in Petrograd (which had been renamed from Saint Petersburg in September 1914)—the same space in which Goncharova’s controversial solo exhibition had been shown the previous year. Malevich presented thirty-nine entirely nonrepresentational (he called them “nonobjective”) paintings in this exhibition, all but one of them unframed. Nine of the paintings bore individual titles—including some fairly ornate titles such as Pictorial Realism of a Boy with a Knapsack: Color Masses in the Fourth Dimension (1915)—whereas the other thirty canvases were grouped under two general titles: Painterly Masses in Motion and Painterly Masses at Rest, as designated in the exhibition catalog and on large handwritten sheets of paper pinned to the gallery walls. These sheets are visible in the only surviving photograph of the exhibition (fig. 5.1), as are about half of the paintings that he showed in the exhibition. But the most striking aspect of this photograph is that it shows that Malevich had installed his Black Square (originally titled Quadrilateral) (1915) in the uppermost corner of the room, unmistakably occupying the place of the holiest icon in the Orthodox red corner.

Figure 5.1. Photograph of Malevich’s installation at The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0.10 (Zero-Ten), December 1915 to January 1916

Alexandre Benois, the most prominent of the Petersburg symbolists, immediately recognized the implication: “Without a number but high up in a corner just below the ceiling in the holy place, is hung a ‘work’ undoubtedly by the same Mr. Malevich, representing a black square against a white background [oklad45]. There can be no doubt that this is an ‘icon.’”46 But for Benois the pictorial blankness and vacancy of this icon were deeply troubling. He regarded the painting as viciously iconoclastic, a negating or nullifying of the Christian iconic tradition and the ideals that it stands for: this “new icon of the square” proclaimed that “everything that we hold sacred and holy, everything that we loved and lived for has vanished.”47 Indeed, he argued (in lines that could well have been written by Rookmaaker48) that the logic of this negation was “nothing less than a call for the disappearance of love, that fundamental principle that provides us with warmth and without which we would inevitably freeze to death and perish.”49 Interestingly, Benois was not dismissive of Malevich but rather considered him “a representative of his time”: His work was “not simply a joke, not simply a challenge, not a small casual episode. . . . [N]o, this is one of those acts of self-assertion, a beginning that . . . reduces all to ruin.”50 But if such an icon was indeed representative of the age, then Benois was profoundly unsettled: “How to pronounce the spell which will once more bring back the cherished images of life upon the background of the black square?”51

Benois’s sharp response should give us reason for pause, but so too should the fact that Malevich thought that it frankly missed the point, insofar as it received the work solely through a pictorial theory of art. Malevich responded to Benois directly, forthrightly acknowledging that he regarded Black Square as “a single bare and frameless icon of our times,” but he contested the critic’s assumptions about what this implied.52 Perhaps the nakedness and blankness of this icon had indeed been meant to displace Benois’s “cherished images of life,” but Malevich questioned why and how Benois was linking life with pictorial familiarity:

I would very much like to ask you and everyone: is the image of what you are looking for drawn clearly enough? The ancient Magi had a guiding star (the care of the Most High). Do you have an indicator and will you be able to recognize what you are looking for? Are you sure that you will not walk right past it, like the Jews with Christ? Who knows, maybe these new people are to be found here a thousand times over, down some Bath-House Lane [presumably a reference to Christ eating with prostitutes and sinners, e.g., Mk 2:13-17].53

So Malevich pressed Benois on precisely this question: “Who has been entrusted with recognizing the living?”54 If Benois considered Black Square a nihilist icon, Malevich spoke of it as if it were brimming with the life of a Hodegetria icon: “The square is a living, royal infant,”55 an “embryo of all possibilities.”56 How can that difference in interpretation be adjudicated?

Malevich was quite serious about positioning the Black Square in the holy corner. Several years later he reflected on the meaning of this placement:

I see the justification and true significance of the Orthodox corner in which the image stands, the holy image, as opposed to all other images and representations of sinners. The holiest occupies the center of the corner, the less holy occupy the walls on the sides. The corner symbolizes that there is no other path to perfection except for the path into the corner. This is the final point of movement. . . . Whether you were to walk in the heights (the ceiling), down below (the floor), on the sides (the wall), the result of your path will be the cube, as the cubic is the fullness of your [three-dimensional] comprehension and is perfection.57

The sobriety of this statement, and the total lack of sarcasm about the symbolic gravity of the red corner, only deepens the questions about what it means to present this black, seemingly vacant icon in the position of “the holiest.” What notion of the holy is Malevich advancing? Is this a negation of Christian theology, or is it a theology via negativa? Is Black Square a figuration of (ontological) void or a (semiotic) voiding of figuration? An icon of the death of God or an icon of God’s unrepresentability? Has the holy corner been appropriated for mockery, lament or apophatic meditation? Is this an act of modernist hubris or theoaesthetic humility?

These questions come into somewhat sharper focus in the wider context of his life and work. Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935) was the eldest of fourteen children (five of whom died during childhood). He was born in Kiev, Ukraine, to parents of noble Polish descent who had fled Poland amidst the violence of the 1863 uprising against the Russian Empire.58 His parents were proudly Polish Catholic, naming their firstborn son after the fifteenth-century Catholic prince and patron saint of Poland, Kazimierz (Kazimir).59 Malevich’s uncle Lucjan had been a Catholic priest (who was hanged for his role in the uprising), and the family strongly encouraged young Kazimir likewise to go into the priesthood.60 He threw himself into painting instead, which, in the words of Alain Besançon, “he took up with the seriousness of a religious vocation.”61

Similarly to Kandinsky, Malevich first produced paintings that were quasi-impressionist landscape studies,62 but by 1906 he had moved to Moscow and burned many of these earlier “realist” works. Moscow exposed him to intense political unrest (following the revolution of 1905) and also to the most advanced forms of French and Russian symbolist painting—he was particularly interested in Gauguin. In 1907–1908 Malevich began exploring religious subject matter in a symbolist mode, taking unconventional approaches to traditional Christian themes such as Prayer (1907), The Triumph of Heaven (1907), Assumption of a Saint (1907–1908), Adam and Eve (1908), Tree of Life (1908) and Shroud of Christ (1908). One is struck not only by the meticulous patterning and sumptuous color throughout these paintings—drawing heavily from both Russian symbolist painting63 and the newly restored Orthodox icons on view in Moscow—but also by his repeated use of black (rather than golden) halos to designate the holiness of his figures.64

By 1910–1912 Malevich became deeply influenced by Goncharova—John Milner refers to her as “Malevich’s mentor” during these years65—and like her, he was intensely interested in traditional Christian icons. Parallel to Goncharova’s move toward a uniquely Russian modernism, and further augmented by his interest in radical politics, Malevich began making paintings of peasants—a motif that he would return to throughout his life. As Milner argues, these paintings were not only politically but also religiously charged: “Malevich was not simply painting peasants; he was observing the Old Believers”—a sect of Orthodox Christians who rejected the seventeenth-century liturgical reforms to the Russian Orthodox Church66 and “followed their beliefs at least as devoutly as the peasants of Brittany [with whom Gauguin had been preoccupied].”67 Malevich was drawn to the “isolation, cohesion, and simplicity of the Old Believers” as they sought to preserve “a cultural identity that was both Russian and defiant, sustaining a cultural heritage and a devout way of life that had been swept away elsewhere.”68 Works like Praying Woman (1911–1912) and Peasant Women in Church (1911–1912), which he exhibited at the Donkey’s Tail exhibition,69 depict peasant women crossing themselves conspicuously in the manner of the Old Believers (with two extended fingers rather than the reformed convention of two fingers joined with the thumb). Malevich used his lifelong friend Ivan Kliun as a model for several of his paintings of Old Believers, deploying an overtly “icon-like format” in paintings like Completed Portrait of Ivan Kliun (1913) and in multiple versions of The Orthodox (1912).70 Milner summarizes Malevich’s work during this period as “introducing cubism to the Russian icon,” developing an iconic visual language “that would follow Malevich to the end of his life.”71

Like Mondrian, Malevich took huge leaps in his thinking about art between 1912 and 1916. He undertook rigorous examinations of French cubism and Italian futurism in his painting practice, but he also began collaborating with poets and intellectuals who challenged his thinking. The Stray Dog (Brodiachaia Sobaka) cabaret was one such gathering of avant-gardists that generated an enormous amount of artistic energy72—the high point of which might be marked at December 1913 with two performances of the futurist opera Victory over the Sun (Pobeda nad solntsem).73

Victory over the Sun was a collaborative project involving the poets Aleksei Kruchenykh (1886–1968) and Velimir Khlebnikov (1885–1922), musician Mikhail Matiushin (1861–1934), and visual artist Malevich, who designed all the sets and costumes. The plot celebrated the “strongmen of the future,” who succeed in imprisoning and overthrowing the sun—a symbol for natural temporal cycles and the “light” of natural reason.74 Significantly, Malevich retroactively dated the conception of Black Square to the designs he made for the stage curtain for scene three of the opera, which portrayed the eclipse and “burial” of the sun, as well as to the design for the pallbearers who presided over the sun’s funeral wearing black squares on their chests and hats. In this context we might interpret Black Square as some kind of ideological eclipse.

One of the most particular aspects of this opera was the use of zaum, an experimental language created by Kruchenykh and Khlebnikov to produce “dislocations” within the operation of everyday language—a “making strange” (ostranenie), to borrow Viktor Shklovsky’s term. Zaum was a kind of strict formalism that sought an “attunement to the material fabric of language,”75 but it was specifically aimed at accessing a mode of meaning that transcends formal relationships. In Russian, zaum (pronounced “za-oom”) combines the prefix за (beyond or outside of) with the noun ум (mind, reason, intellect), such that it is often translated into English as “transrational,” “beyond reason,” “beyond the mind” or (in Paul Schmidt’s translation) “beyonsense” (subtly alluding to yet differentiating it from nonsense).76

According to Khlebnikov, “Beyonsense language [zaumny yazyk] means language situated beyond the boundaries of ordinary reason, just as we say ‘beyond the river’ or ‘beyond the sea.’”77 He understood zaum as opening the possibility for language to operate on multiple “word planes,” accessing a “language of the birds,” a “language of the stars,” even a “language of the gods.”78 And for this reason, he was interested in any form of language that opened zones of defamiliarized meaning, ranging from prelingual speech (children’s babble) to supralingual “tongues” (angelic language, glossolalia). As Sarah Pratt has argued, Khlebnikov was intensely interested in the possibility of zaum language functioning as (or at least in ways parallel to) holy icons.79 Pratt locates Khlebnikov within the Orthodox tradition of the “holy fool” (iurodstvo), even if he sometimes appeared “an unorthodox Orthodox holy fool.”80 In fact zaum was drawn from sources that gave it strong theological undertones: Kruchenykh’s contributions to zaum were, for example, heavily influenced by ethnographic field reports on Christian glossolalia (speaking in tongues), particularly as published in D. G. Konovalov’s study of Religious Ecstasy in Russian Mystical Sects (1908).81

Long after the opera, zaum poetry continued to be central to Malevich’s development, propelling him to break with representation in pursuit of “zaum painting.” In the summer of 1913 Malevich wrote to his collaborator Matiushin, offering his understanding of their common objective:

We have come as far as the rejection of reason, but we rejected reason because another kind of reason has grown in us, which in comparison with what we have rejected can be called beyond reason [zaumnyi], which also has law, construction, and sense, and only by learning this shall we have work based on the law of the truly new “beyond reason.”82

His pursuit of an intelligibility “beyond reason” was thus oriented by a sensitivity to another kind of “law” that was in some way higher or deeper than logical formulation allowed. At the heart of Malevich’s interest in zaum—whether in poetry or painting—was the conviction that the domains of human reasoning and language rely on creaturely functions that cannot ultimately account for themselves: the very possibility of intelligible thought and speech is given by and grounded in a reality that necessarily exceeds their reach and is thus essentially unthinkable and unspeakable. The aim of zaum was to foster a manner of reasoning that felt for these outer edges of thinking in order to gesture beyond them. According to Malevich, the highest function of art is to jolt the recognition that the daily communication of “each man is only a conduit for the infinite ocean of knowledge and power that lies behind mankind.”83

As announced on a leaflet distributed at the 0.10 exhibition, one of Malevich’s earliest names for his new austere form of abstract painting was “zaum realism.”84 The other name Malevich applied to this work—the name that stuck—was “suprematism,” a name meant to designate the supremacy of formal color energy as the primary mode of meaning in painting. Aleksandra Shatskikh highlights the religious derivation of this term: “The word [suprematism] had its roots in Malevich’s native language, Polish, to which it had come, in turn, from the Latin of the Catholic liturgy [supremacia].”85 Andréi Nakov notes that in fact “Latin phrases are sprinkled throughout [Malevich’s] letters. . . . His vocabulary at the time was marked by numerous references to Christianity and to the Bible, testifying to the religious education deeply imprinted in his cultural background and which was later to make up the cultural habitus of his philosophical pronouncements.”86

This returns us to Black Square, which was visual zaum in at least two senses. On the one hand, it was a strict formalism that evacuated the representational functions of painting and instead began composing works based entirely on the dimensions of the canvas itself.87 Malevich considered this “a new, healthier form of art” over against the “moldy vault” of academic tradition, whose pictorial conventions he believed had become self-indulgent, “fattened on wine and debauched Venus de Milos.”88 There was a moral rigor to his defiance: “You will never see sweet Psyche’s smile on my square, and it will never be a mattress for love-making.”89 And this formalism also had sharp political edges to it: “Imitative art must be destroyed like the imperialist army. . . . Just as in the old days the West, East, and South oppressed us economically, so it was in art. . . . The creative construction of the new art has produced the Suprematism of the square.”90

On the other hand, however, this formalizing of pictorial language was motivated specifically by the desire to gesture beyond the traditional pictorial “reasoning” of painting. At the core of Malevich’s philosophy was the pursuit of “something more subtle than thought, something more light [sic] and more flexible. To express this in words is not merely false, but quite impossible. This ‘something’ every poet, painter, and musician feels and tries to express, but when he is about to do so, then this refined, light, flexible ‘something’ becomes ‘She,’ ‘Love,’ ‘Venus,’ ‘Apollo,’ ‘the Naiads [water nymphs],’ and so on.”91 Against this tendency, Malevich wanted to know if it was possible to gesture toward the “something more subtle than thought” without condensing it into a recognizable “figure” of thought. Suprematist painting was thus conceived as a rigorous pursuit of “objectlessness” (bespredmentnost).

In this sense, there was a profound desolation inscribed in the Black Square, but not necessarily in the way that Benois saw it. Malevich repeatedly referred to the objectlessness of his paintings as a “desert” into which he ventured like an ascetic pilgrim seeking purification. In his letter to Benois, Malevich vowed that he would muster the “strength to go further and further into the empty wilderness. For it is only there that that transformation can take place.”92 In this way he repeatedly framed his painting practice as analogous to the ascetic mysticism of the desert fathers: “The ascent to the heights of nonobjective art is arduous and painful. . . . The familiar recedes ever further and further into the background. . . . No more ‘likenesses of reality,’ no idealistic images—nothing but a desert! But this desert is filled with the spirit of nonobjective sensation which pervades everything.”93 And here we glimpse the extent to which Malevich’s work was rooted in apophatic or “negative” theology—a mode of theology that meditates on the absolute Fullness and Otherness of God by way of negating the verbal, visual and conceptual forms used to signify (and to “grasp”) God. The long traditions of Christian apophatic theology valued this “negative way” not as a means of negating God but as a means of recognizing the problematic extent to which creaturely speech and thought reduces God to an object—a being among other beings—forgetting that God precedes and pervades the Giving of being itself and of the very possibility of speech and thought. The absence of figuration in Malevich’s work, his visual asceticism, ultimately has less to do with vacancy than it does with recognizing a pervasive fullness that surpasses and displaces all figurative appearance. Namely, it is a fullness perceived not by sight but by “feeling”: he believed that the highest form of painting is that “which gives the fullest possible expression to feeling as such and which ignores the familiar appearance of objects.”94 And thus, “this was no ‘empty square’ which I had exhibited but rather the feeling of nonobjectivity.”95

For Malevich white was the color of the suprematist desert.96 In a whimsically formulaic passage he spelled out the calculus of Black Square: “The square = feeling; the white field = the void beyond this feeling.”97 By 1917 he began making paintings preoccupied entirely with the white field, the wholly imperceptible “beyond” all feeling. He painted deserts of White on White (1918) in which “objectless” forms—in one case a rotated square (“square = feeling”)—appear in subtly varying hues of white; and by May 1923 he presented paintings composed only of a singular blank whiteness—paintings that he collectively referred to as the “Suprematist Mirror.”98

Malevich’s work was theologically charged throughout his career, but around 1920—in the midst of the most tumultuous years of the Russian Revolution (1917–1923)—he began connecting it more explicitly to Russian Orthodox Christianity. In a letter to Mikhail Gershenzon in the spring of 1920 he confessed:

Now, I have returned, or entered into the world of religion. . . . I go to church, I look at the saints and at all the protagonists of the spiritual world, and I see in myself and perhaps in the whole world that the moment for religious change is beginning. . . . I see in Suprematism, in the three squares and the cross, a beginning that is not just pictorial, but encompasses everything.99

This return to religion corresponded with a return to painting (which he had abandoned for a period of time to focus entirely on teaching and writing) and a reintroduction of figurative imagery—specifically religious imagery. Matthew Drutt summarizes this as “the period during which the spiritual dimensions of Suprematism became more formally linked with religious painting through Malevich’s adaptation of the Orthodox cross.”100 He produced numerous paintings of crosses, including Suprematism (Hieratic Suprematist Cross) (1920–1921), Suprematism (White Suprematist Cross) (1920–1921), Suprematism of the Spirit (or Suprematism of the Mind) (1920) and multiple remakes of Black Cross (1920). He also painted multiple versions of distinctly Russian Orthodox crosses (depicted with an angled foot bar)—all titled Mystic Suprematism (1920–1922) (and sometimes given differentiating subtitles like Black Cross Red Oval). As Nakov puts it, Malevich began “‘crucifying’ his initial square, so to speak.”101

At the same time, Malevich continued to devote a great deal of energy to writing, especially his essay God Is Not Cast Down (written in 1920 and published in 1922).102 In this essay he argued that “man has divided his life into three paths: the spiritual or religious, the scientific or factory, and that of art. . . . They are the three paths along which man moves towards God.”103 Though they often appear to be in conflict—especially in the violent and volatile early years of the Soviet state—Malevich saw them as ultimately complementary and convergent: three concrete paths that find their beginning and end in the transcendent God. As he saw it, all human thinking and working are pressed along these paths through “a process, an activity of an unknowable stimulus [vozbuzhdenie].” In other words, we always already find ourselves existing and stimulated into consciousness in such a way that ultimately we cannot account for the Giving of this stimulus in the first place; we can only receive it and work within it. There is thus an Unthinkable on which all thinking relies, and “that is why Nothing [the Unthinkable] has an influence on me, and why Nothing, as an entity, determines my consciousness; for everything [all that is thinkable] is stimulus.”104 Malevich’s “Nothing” is thus not an ontological absence but a means of designating a fullness that is intrinsically imperceptible and ineffable: “infinity has no ceiling or floor, no foundations or horizon, and, therefore, the ear cannot catch the rustle of its movement, the eye cannot see its limit, and the mind cannot comprehend.”105 Malevich’s contention is that the fullness of the infinite can only appear (phenomenologically speaking) as a “nothing, i.e. incomprehensible to consciousness.”106

Malevich’s appeal to “Nothing, as an entity” is thus not nihilistic but is rather radically apophatic. Despite his bombastic rhetoric, Malevich’s theology was centered on the acknowledgment of human limit: “There stands before God the limit of all senses, but beyond the limit stands God in whom there is no sense. . . . His senselessness should be seen in the absolute final limit as nonobjective.”107 Malevich proclaims that “God Is Not Cast Down” because God is not an object; there is never any sense in which it could be intelligible for the Giving of being as such to be “cast down.” According to Besançon, “Malevich sees God as being’s beyond” for which the only appropriate signifier is a kind of “nothingness” (no-thingness).108 Malevich’s ideology thus has much less to do with Russian nihilism than it does with the Christian mysticism of Pseudo-Dionysius, for whom God is “the wholly unsensed and unseen . . . beyond every denial, beyond every assertion.”109

Jean-Claude Marcadé urges us to recognize that “neither pictorial Suprematism nor Suprematist philosophy is iconoclastic or nihilist”; rather it is a form of “‘transmetaphysical thought’ that seeks a new relationship with God,” who is beyond the reach of the representational operations of pictorial imagination and philosophical metaphysics alike.110 Malevich’s apophaticism obviously does engage in a kind of iconoclasm, but Marcadé argues that it is an iconoclasm that leaves the domain of the icon intact, even as it forces its imagery to become nonpictorial. As T. J. Clark puts it, “part of the point was the non-naming, the unmeaning” that takes place precisely in a framework of expectations for paintings to conduct namings and meanings.111 As Malevich himself said, “The square is not an image, just as a switch or a socket is not yet an electric current.”112 The “yet” in that statement is key: the square is the open (im)possibility of seeing an image of God.

God Is Not Cast Down cut directly against the grain of Soviet materialism, and as a consequence it was harshly criticized. With the death of Lenin in 1924 the political scrutiny directed toward Malevich increased exponentially, and the remaining years of his life were exceedingly difficult. In June 1926 he organized an exhibition of artists associated with GINKhUK (State Institute of Artistic Culture), which was met with a scathing article by the critic Grigory Seryi: “A monastery has taken shelter under the name of a state institution. It is inhabited by several holy crackpots who, perhaps unconsciously, are engaged in open counterrevolutionary sermonizing, and making fools of our Soviet scientific establishments.”113 It was a slanderous and politically motivated hit-piece, but Seryi’s association of the institute with a monastery had merit: the exhibition was designed to mimic an Orthodox sanctuary, complete with what amounted to an iconostasis screen composed of a giant suprematist banner flanked on three sides by remade versions of Black Square, Black Circle and Black Cross. Seryi’s complaints led to formal investigations of Malevich, and by the end of the year he had been fired and GINKhUK closed.

In 1928 his longtime friend Ivan Kliun wrote a letter to Malevich appealing to him to rethink his commitment to objectlessness:

You must take up the brush, the time has come; it is time to come out of the desert. I am not deciding the question of what and how you must paint, but I know that you must paint a picture, and you yourself will see how your voice will ring out firmly, as it once did. Now it is necessary. . . . Only the hammer and sickle will help you get out of the desert of objectlessness.114

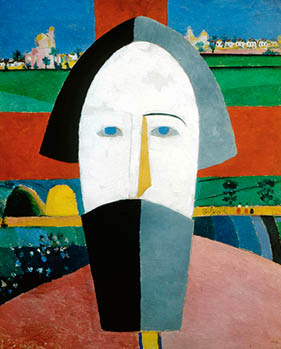

Malevich’s paintings did come out of the desert, but it was not the hammer and sickle that brought them out; it was once again religious imagery. Malevich’s Head of a Peasant Man (1929–1932) (fig. 5.2) riffed on the portraits he had painted of Kliun twenty years earlier, but this time he explicitly painted him as an image of Christ. A red cross form appears immediately behind this bearded figure’s head, borrowed directly from an iconic motif of Christ’s face that was well known throughout Russia, and he allocated the mystical color white to the face of Christ.115 He played up the iconic overtones by placing the painting in a painted gold frame. According to Alfia Nizamutdinova, this is the image of “Malevich’s Golgotha,” and as such it as “the key to understanding the peasant theme in Malevich’s oeuvre and the artist’s own personal philosophy of the world.”116

Figure 5.2. Kazimir Malevich, Head of a Peasant Man, 1929–1932

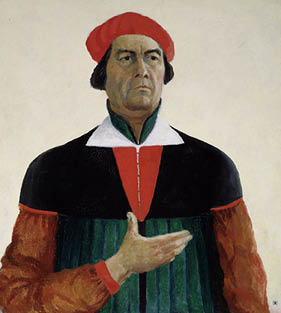

In the midst of a wave of Soviet antireligious measures, Malevich defiantly painted overtly religious imagery. In the late 1920s and early 1930s he painted and sketched numerous “mystics” who bear the sign of the Russian Orthodox cross on their otherwise blank faces, hands and feet. Praying Figure (c. 1922) is a particularly striking example but so too are Face with Orthodox Cross (c. 1930–1931), Black Head with Orthodox Cross (1930–1931), Mystical Black Face (c. 1930–1931), Figure with Arms Crossed (c. 1930), Figure Forming a Cross (1930–1931) and Female Figure with Arms Extended Crosswise (c. 1930–1931). One of Malevich’s last paintings is The Artist (Self-Portrait) (1933) (fig. 5.3). Though initially triggering references to Italian Renaissance painting, the odd pose more directly references Hodegetria icon paintings (see fig. 5.4)—the role of the artist is to be “one who points the way.” Malevich does indeed point, but without an image of the incarnate Christ child; he points us beyond the frame of the canvas toward the unseen, or toward what is in fact altogether unseeable. In many ways this self-portrait is a figurative counterpart to the apophaticism of his earlier suprematism. Tellingly, in the lower right corner Malevich signed the painting only with a black square.117

Figure 5.3. Kazimir Malevich, The Artist (Self-Portrait), 1933

At the same time that Malevich was developing his apophatic, nonobjective paintings in Russia, some of the most radical artists in the European avant-garde, the Dadaists, were beginning to meet and collaborate in Germany and Switzerland—and, as we will see, developing in ways that function as striking theological counterparts to Malevich.118 Within the canons of Western art history Dada is generally represented as the most blatantly nihilistic moment of the modernist avant-garde—an antirationalist, anarchist, even misanthropic revolt against Western social values. And in fact there is much to commend this view: there are numerous examples and proof-texts one might cite to convey the extent to which Dada “radiated a contemptuous meaninglessness,” to borrow Hal Foster’s memorable phrase.119 Within Christian circles Dada usually functions as an epitome of modernism at its theological worst, a tragic convergence (or inverted apotheosis) of everything that is most problematic about the post-Christian avant-garde. The prevailing view in these circles still generally accords with Hans Rookmaaker’s description of Dada as “a nihilistic, destructive movement of anti-art, anti-philosophy . . . a new gnosticism, proclaiming that this world is without meaning or sense, that the world is evil—but with no God to reach out to.”120 And while this accurately describes some of what Dada was, there is much else that it doesn’t account for. The historical unfolding of Dada, especially from its origins in Zurich, is much more variegated and interesting than its typical relegation to nihilism—and in fact much more theologically substantive.

Figure 5.4. Lambardos Emmanuel, The Virgin Hodegetria, first half of the seventeenth century

The academic literature on Dada has swelled over the past few decades, and in the process it has become increasingly clear that, as Debbie Lewer puts it, “there are almost as many ‘Dadaisms’ as there were Dadaists.”121 There was remarkable intellectual diversity and difference of purpose not only between the various Dada groups—Zurich Dada had a very different sense of itself than did Paris Dada, for instance—but also among the original Dadaists122 themselves, who continuously struggled with each other over the meanings and implications of what they were doing. These meanings were deeply political, aesthetic and philosophical, but they were also intensely theological—and they were so from the beginning.

Though Dada would later become strongly associated with influential artists in Berlin, Paris and New York (e.g., Hausmann, Picabia and Duchamp), its initial formation occurred in Zurich among an international group of artists who fled to neutral Switzerland in the early months of World War I. By all accounts Hugo Ball (1886–1927) stands at the fountainhead of Dada “activity” (he objected to calling it a movement or an -ism), and he was undoubtedly one of its most articulate exegetes and commentators.123 Ball was raised in a devoutly Catholic home in a predominantly Protestant part of Germany, shaping him in ways that would be deeply important throughout his life.124 His renunciation of Christianity roughly corresponded to the beginning of his studies at the University of Munich, where from 1906 to 1910 (with one year at the University of Heidelberg) Ball studied philosophy and began writing a doctoral dissertation on Friedrich Nietzsche.125 During this time he read voraciously in the fields of socialist and anarchist political theory and (under the influence of Nietzsche’s philosophy of art) became deeply interested in poetry and theater. In 1910 he left Munich abruptly, without finishing his PhD, and moved to Berlin to pursue a career in theater. Over the next decade Ball would become a key contributor to some of the most radical artistic experiments in the European avant-garde, including the launch of Dada in February 1916. Throughout this time, however, he was wrestling with difficult theological questions and concerns, and by the summer of 1920 Ball had reconverted to Catholicism and devoted the remaining seven years of his life126 to ascetic religious practice and theological study.

And thus the question that will orient the rest of this chapter: How should we understand Hugo Ball’s Dadaism in relation to his Christianity? Was there a sharp discontinuity between the two, such that his conversion was a radical break; or was there in fact some kind of deep continuity throughout, such that the ostensible nihilism of his Dadaism was actually underwritten by a deeply serious theological struggle? In short, what kinds of theology were in play in Zurich Dada?127

The birth of Dada is often dated to February 5, 1916, the opening day for the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich.128 Ball’s advertisements for the cabaret announced “a group of young artists and writers . . . whose aim is to create a center for artistic entertainment,” featuring performances and readings at daily meetings.129 The young collaborators who joined Ball would become central to the life of Dada (internationally) over the next few years, including Emmy Hennings (his partner and future wife), Hans Arp, Sophie Taeuber, Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco (often accompanied by his brother Georges), Richard Huelsenbeck, and later Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling.

The numerous events and soirées that took place at the cabaret were notoriously transgressive and seemed to relish the offensively nonsensical. Concerts were played on typewriters, kettledrums, rakes and pot covers and were often accompanied by an out-of-tune piano. Poems were recited in French, German and Russian—languages spoken on both sides of the war—and soon the poems became indecipherable altogether. A common feature of the Dada soirée was the “simultaneous poem,” consisting of three or more participants speaking, singing, whistling or bellowing different “poems” at the same time. This simultaneity generally brought together a mixture of high poetry, popular songs, boring journalistic ramblings and nonsense word sequences; and these contrapuntal recitations were then often accompanied by an assortment of inorganic noises: crashes, sirens, the beating of a giant drum, an rrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr drawn out for several minutes and so on. The effect was abrasive and cacophonous, but Ball argued that for the sensitive viewer the implications of these performances are actually remarkably subtle, even heartbreaking:

The “simultaneous poem” has to do with the value of the voice. The human organ represents the soul, the individuality in its wanderings with its demonic companions. The noises represent the [material, cultural and spiritual] background—the inarticulate, the disastrous, the decisive. The poem tries to elucidate the fact that man is swallowed up in the mechanistic process. In a typically compressed way it shows the conflict of the vox humana [human voice] with a world that threatens, ensnares, and destroys it, a world whose rhythm and noise are ineluctable.130

This motif of the vulnerable human person threatened by (and protesting against) the cool violence of mechanized modernity is recurrent throughout Ball’s thinking and is central to the concerns that drove development of Dada—and the development of Dada theology.

Whatever theological content was in play in the Cabaret Voltaire was, however, pivoting on a radically unconventional theory of art—one that relentlessly demeaned aesthetic quality, craftsmanship and professionalism. The effect—indeed the stated intention—was to shift the hermeneutical center of gravity from the aesthetic character of the art object to the critical social consciousness implied in the artist’s activity:

For us art is not an end in itself—more pure naïveté is necessary for that—but it is an opportunity for true perception and criticism of the times we live in. . . . Our debates are a burning search, more blatant every day, for the specific rhythm and the buried face of this age. . . . Art is only an occasion for that, a method.131

The “age” in which Dada emerged was that which had launched World War I, precisely as the logics of technological industrialization and philosophical idealism were converging with unspeakably devastating effects. As European nations devoted themselves to industrialized warfare on an unprecedented scale, the Dadaists devoted themselves to sardonic “nonsense” and mean-spirited laughter. Ball understood this as an ethical maneuver, a means of establishing “distance”132 from which to stand “against the agony and the death throes of this age.”133 In a diary entry from mid-April 1916, when the Cabaret Voltaire was little more than two months old, Ball declared: “Our cabaret is a gesture. Every word that is spoken and sung here says at least this one thing: that this humiliating age has not succeeded in winning our respect.”134 And with this he launched into a series of deflationary taunts:

What could be respectable and impressive about it? Its cannons? Our big drum drowns them. Its idealism? That has long been a laughingstock, in its popular and its academic edition. The grandiose slaughters and cannibalistic exploits? Our spontaneous foolishness and our enthusiasm for illusion will destroy them.135

Over against the calculable mechanized efficiency of both the frontline machine gun and the backline munitions factory (and the rhetorical systems that held them together), Zurich Dada mobilized itself into a theater of incompetence, confusion and traumatized powerlessness. It protested against abusive cultural powers, and it did so through deliberately pathetic gestures. These gestures were tactical: “As no art, politics, or knowledge seem able to hold back this flood [of cultural pathologies], the only thing left is the practical joke [blague] and the bloody [or bleeding] pose.”136 In this way Dada’s spectacle of unprofessional pranks and displays of weakness was meant to function as a desperate ethical refusal.137 As Hal Foster has put it, “Ball regarded the Dadaist as a traumatic mime who assumes the dire conditions of war, revolt, and exile, and inflates them into buffoonish parody.” But this was parody with principles: “Dada mimes dissonance and destruction in order to purge them somehow.”138

Hans Arp once described the cabaret as full of people “shouting, laughing, and gesticulating. Our replies are sighs of love, volleys of hiccups, poems, moos, and meowing of medieval bruitists. . . . We were given the honorary title of nihilists.”139 But this title is clearly a misleading designation for many of the Zurich Dadaists—particularly for Hugo Ball. Far from a nihilistic embrace of “nothingness,” Ball asserted that “what we call dada is a farce of nothingness [Narrenspiel aus dem Nichts] in which all higher questions are involved; a gladiator’s gesture, a play with shabby leftovers, the death warrant of posturing morality and abundance.”140 Ball’s characterization of Dada as a farcical nihilism is thus coupled with a disarming list of metaphors that do indeed call up high questions: (1) the gesture of a gladiator whose life is at stake for entertainment (what is the value of human life?), (2) a playful recovery of the detritus of consumer culture (what are our metrics of value?), and (3) the severest indictment of false moralities designed to augment wealth (what is the good life, morally or materially?). One might even say that Ball sought to invert the charge of nihilism, accusing the established powers—“This age, with its insistence on cash payment, has opened a jumble sale of godless philosophies”141—of manifesting a nihilism far deeper and more death-oriented than any “simultaneous poem” performed at the Cabaret Voltaire.

In his most evocative summary of Dada, Ball announced, “What we are celebrating is both buffoonery and a requiem mass.”142 This disorienting meld of images—an aggressive eschewal of rationalism, professionalism and politeness (buffoonery) commingled with formal liturgical lamentation (Requiem Mass)—provocatively signals a theological self-understanding intertwined with the social and political content of Dada’s protests. Or, taking an even more disarming religious image, Ball once compared Dada to “a gnostic sect whose initiates were so stunned by the image of the childhood of Jesus that they lay down in a cradle and let themselves be suckled by women and swaddled. The Dadaists are similar babes-in-arms of a new age.”143 Erdmute Wenzel White is quite right to argue that in Ball’s case we mustn’t allow the apparent foolishness and bombastic rebellion to “disguise the intense spiritual longing that informs all his life and work.”144

Contrary to general perception, the events in the Cabaret Voltaire made surprisingly frequent references to religious images and motifs. On June 3, 1916—in the middle of the summer and amidst ongoing war reportage (most recently from the disastrous Battle of Jutland)—the cabaret presented a performance of Ball’s Krippenspiel (Nativity Play), a simultaneous poem and bruitist “noise concert” that corresponded to and accompanied readings from the Gospel accounts of the birth of Christ.145 Short adaptations of the biblical narrative were read aloud while actors performed the scenes behind a diaphanous screen, using nonword vocalizations and various objects to sonically construct the settings and activities of the nativity.

The Krippenspiel unfolded in a series of seven scenes. The first two scenes portrayed the annunciation to the shepherds and the setting of the stable in the rural “silent night”—which was in fact full of sound146—and then the scenes run through the journey of the magi. The final scene jolts the narrative forward into a prophetic foreshadowing of the crucifixion, culminating in an uproar of all the characters and animals yelling, jeering, bellowing, mooing and wailing. The final crescendo gives way to “nailing and screaming. Then thunder. Then bells.” And (most likely) the last words spoken in the play had been handwritten into the otherwise already typed script: “And as he was crucified / much warm blood was shed.”147 Performed in the summer of 1916, the violence of this final scene would have had a twentieth-century referent as much as a first-century one. The Krippenspiel situated the brutality of the war within a theological framework, rendering a palpable image of human violence having “bloodied and soiled the good God.”148 Despite the occasionally cacophonous soundscape of this summer nativity, the performance, according to Ball, had “a gentle simplicity that surprised the audience. The ironies had cleared the air. No one dared to laugh. One would hardly have expected that in the cabaret, especially in this one. We welcomed the [Christ] child, in art and in life.”149

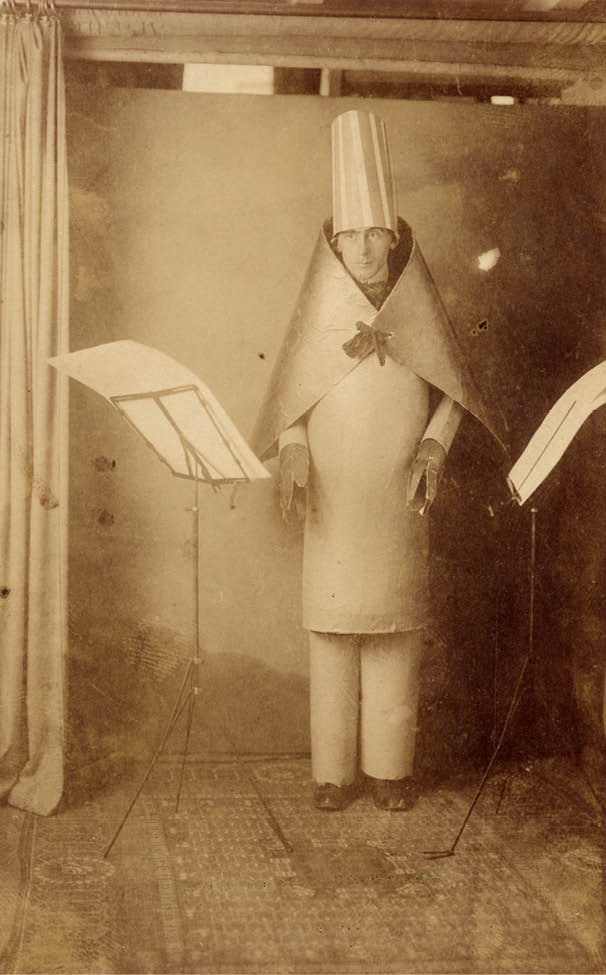

Perhaps the most renowned of the cabaret’s events occurred about three weeks later on June 23, 1916, with a performance that has come to be known as the “magic bishop.”150 Ball appeared on stage to perform a series of his new “sound poems” (Lautgedichte)—poems that were carefully constructed sequences of unrecognizable sound-words.151 He wore a costume of rigid, shiny blue cardboard cylinders, such that he stood on the stage “like an obelisk” (fig. 5.5). A cardboard cape (he called it “a huge coat collar”) hung off his shoulders like a priestly cope, colored scarlet on the inside and gold on the outside; and on his head he wore a tall cylindrical blue-and-white-striped “shaman’s hat” (Schamanenhut). The handwritten texts of his poems were placed on three music stands that stood in a semicircle around him on the stage, emphasizing the musical status of the sound poems. Unable to walk in his costume, Ball was carried onto the darkened stage, and as the lights came up he began to read “slowly and solemnly”:

gadji beri bimba

glandridi lauli lonni cadori

gadjama bim beri glassala

glandridi glassala tuffm i zimbrabim

blassa galassasa tuffm i zimbrabim

After delivering the entirety of this introductory poem from the central music stand, he turned to the stands on either side, delivering (at least) one poem at each, finally returning to the center for a second recitation of “gadji beri bimba.” At the stand on the right he performed the poem “Wolken [Clouds]” (or Labada’s Song to the Clouds), and then at the left stand he read “Karawane” (or “Elefantenkarawane [Elephant Caravan]”). The poems refused to coalesce into recognizable words, but the sound effects made when read aloud were carefully constructed to correspond to the subject matter alluded to in their titles152: rain from heavy clouds soaks the earth with “gluglamen gloglada gleroda glandridi,” on the one hand, and the heavy “wulubu ssubudu uluwu ssubudu” lumbers onward with the plodding rhythm of a caravan of elephants, on the other.153

Figure 5.5. Hugo Ball in his “magic bishop” costume for a performance of Lautgedichte, 1916

Ball was determined “at all costs” to maintain composure and seriousness throughout the performance, and as he proceeded through the poems he found the performance taking a form he had not intended:

Then I noticed that my voice had no choice but to take on the ancient cadence of priestly lamentation, that style of liturgical singing that wails in all the Catholic churches of East and West. . . . I began to chant my vowel sequences in a church style like a recitative, and tried not only to look serious but to force myself to be serious. For a moment it seemed as if there were a pale, bewildered face in my cubist mask, that half-frightened, half-curious face of a ten-year-old boy, trembling and hanging avidly on the priest’s words in the requiems and high masses in his home parish. Then the lights went out, as I had ordered, and bathed in sweat, I was carried down off the stage like a magical bishop.154

In this figure of the “magical bishop” Ball had encountered something of his Catholic childhood—the half-frightened, half-curious adolescent witnessing a requiem—but in a form that was strangely reclaiming his Dada insurrections and reframing them as some kind of a priestly function. His sound poems suddenly became some kind of prayer by which he found himself both attending and presiding over religious lamentation.

John Elderfield has argued that the sound poems “were close in spirit to Catholic chants,”155 and according to Erdmute White one can trace “a direct line from plainchant to Lautgedichte [sound poetry].”156 The performance had followed a liturgical inclusio format, in which “gadji beri bimba” was recited at both the beginning and the end of the cycle with two “meditations” in between—one oriented toward the sky (clouds) and the other toward the earth (caravan). The first of these—the extremely beautiful poem “Wolken”—hinges on the phrase “elomen elomen lefitalominai” (with only slight variation, this forms the first line of both the first and last stanza). As several commentators have pointed out, this phrase is a direct allusion to Christ’s cry from the cross: “Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani?”—“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mk 15:34 NRSV; cf. Mt 27:46; Ps 22:1).157 Ball’s song to the clouds is structured around Christianity’s most tragic and profound address toward God.

Philip Mann has shown that Ball’s “magic bishop” performance was not only performed in June at the Cabaret Voltaire but was also repeated at the first “public” Dada soirée on July 14, 1916, at Zurich’s Waag Hall.158 Ball prefaced this performance by reading his “Dada Manifesto” in which he flatly declared: “I shall be reading poems that are meant to dispense with conventional language” in the conviction that these poems “have the potential to cleanse this accursed language of all the filth that clings to it, as to the hands of stockbrokers worn smooth by coins.”159 Ball implored his audience to try to hear “The word, the word, the word outside your domain. . . . The word, gentlemen, is a public concern of the first importance.”160 And not just a public concern: the “word outside your domain” is a theological concern of the highest order.

At the center of Ball’s philosophy of language was an acknowledgment of “the power of the living word,” which must be handled with the greatest care: “each word is a wish or a curse.”161 He saw a deep and vital link between a society’s regard for the sacredness of language and the ethical treatment of others: “As respect for language increases, the disrespect for the human image will decrease. . . . It is with language that purification must begin, [and] the imagination be purified.”162 And he believed that the power of language resides not only in the referential function of words but on a more intrinsic, ontological level. For him the relations between vowels and consonants are “heavenly constellations”163 that are in themselves potentially capable of wakening and strengthening “the lowest strata of memory.”164 The abjuring of everyday language in the sound poems was thus conceived as a strategy that was at once political and theological: “In these phonetic poems we totally renounce the language that journalism has abused and corrupted. We must return to the innermost alchemy of the word; we must even give up the word too, to keep for poetry its last and holiest refuge.”165

The “holiest refuge” of poetry was for Ball the sheer recognition of the astonishing miracle that language is intelligible at all—that sounds and markings are capable of mediating the meanings of a world. For Ball this recognition opened a realm of enchantment—he didn’t know how else to refer to the inexplicable link between word and meaning other than to call it “magical.” The true achievement of sound poetry, he argued, was that it “loaded the word with strengths and energies that helped us to rediscover the evangelical concept of the ‘Word’ (logos) as a magical complex image. . . . We tried to give the isolated vocables the fullness of an oath [covenant], the glow of a star [cosmos].”166 On this point Ball delved into Christian mysticism. He was, for instance, familiar with the mystical Lingua Ignota (unknown language) of the twelfth-century abbess Hildegard von Bingen.167 Hildegard’s lengthy indexes of indecipherable word formations—strikingly comparable to Ball’s sound poetry—were constructed for prayer and sacred speech. Perhaps we should take Ball quite seriously when he claimed that “we say the ‘gadji beri bimba’ as our bedtime prayer.”168

In fact, Ball increasingly foregrounded mystical theology in his contributions to Dada events. The fourth public Dada soirée on May 12, 1917 (repeated a week later), included a number of readings excerpted from mystical theological texts: Mechthild of Magdeburg’s Flowing Light of the Godhead (c. 1250–1280), The Great German Memorial (1383–1384) by the Alsatian mystic Rulman Merswin, The Book of the Seven Degrees (c. 1320) by the anonymous Monk of Heilsbronn, a selection from Jakob Böhme’s Aurora (1612), as well as a series of poems (probably written by Hennings) titled “O You Saints.”169 Such a list makes manifest Leonard Forster’s claim that “Dada was not merely the product of a certain set of circumstances, but also stood in a long tradition of mystical utterance.”170 And this tradition provided Ball with a theological framework for even the most bizarre experiments with sound poetry: “I realized that the whole world . . . was crying out for magic to fill its void, and for the word as a seal and ultimate core of life. Perhaps one day when the files are closed, it will not be possible to withhold approval of my strivings for substance and resistance.”171

According to Philip Mann, Ball’s theory of language was increasingly a “theological Realism,” wherein both language and world are sustained and connected by the same logos that speaks and sustains all being. As Mann states, ultimately “it was in Christ, as the Word incarnate, that Ball found this fusion of sign and object.”172 Indeed, as Ball later wrote, “The great, universal blow against rationalism and dialectics, against the cult of knowledge and abstractions, is: the incarnation.”173 Ultimately Ball’s attack on the “journalistic” word was undergirded and oriented by a wager that all words find their origin and telos in the Word made flesh.

Following his conversion in 1920, Ball devoted himself to the study of early Christian and medieval mystical theology, leading to the publication of his book Byzantine Christianity (1923), a study of the church fathers John Climacus, Simeon the Stylite and Dionysius the Areopagite. The Christian apophatic theologian Dionysius the Areopagite174 was especially influential, prompting major shifts in Ball’s theology and in his (retrospective) understanding of Dada. This theologian was decisive in Ball’s movement away from Nietzsche, as he came to believe that “Dionysius the Areopagite is the refutation of Nietzsche in advance.”175 But Dionysius also clarified the meaning of Dada for Ball: he would later claim that the term Dada bore the double inscription of the Areopagite’s initials: “When I came across the word ‘dada’ I was called upon twice by Dionysius. D.A.–D.A.”176 Given the multiplicity of meanings assigned to the word Dada this is almost certainly a revisionist narrative created after the fact, but it does identify an aspect of Ball’s Dadaism that was there from the beginning.177 As John Elderfield writes, “it would be strange indeed if hidden in the alchemy of letters that denoted the most scurrilous of modern movements lies a saint who dreamed of a hierarchy of angels.”178