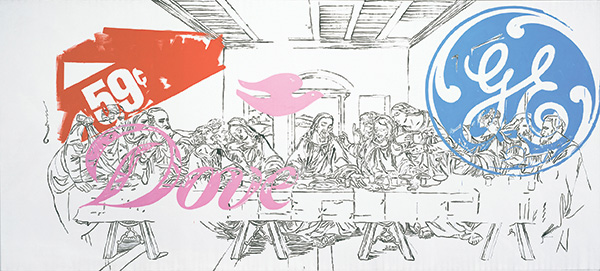

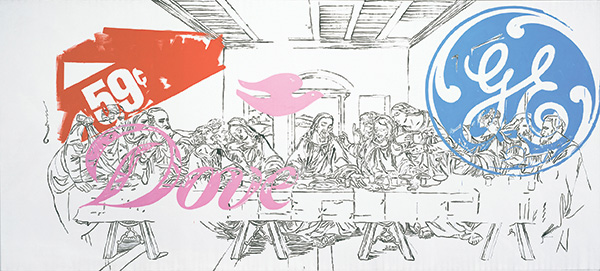

Plate 8. Andy Warhol, The Last Supper (Dove), 1986

The vernacular glance is what carries us through the city every day, a mode of almost unconscious or at least divided attention. . . . The vernacular glance sees the world as a supermarket.

Brian O’Doherty1

Perhaps nothing is more urgent—if we really want to engage the problem of art in our time—than a destruction of aesthetics that would, by clearing away what is usually taken for granted, allow us to bring into question the very meaning of aesthetics as the science of the work of art. . . . And if it is true that the fundamental architectural problem becomes visible only in the house ravaged by fire, then perhaps we are today in a privileged position to understand the authentic significance of the Western aesthetic project.

Giorgio Agamben2

No idea is clear to us until a little soup has been spilled on it. So when we are asked for bread, let’s not give stones, not stale bread. . . . Let’s chase down an art that clucks and fills our guts.

Dick Higgins3

In 1958—two years after Pollock’s tragic death—Allan Kaprow (1927–2006) published his assessment of “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock,” in which he argued that the famous American action painter had “created some magnificent paintings. But he also destroyed painting.”4 Or more precisely, the drip paintings he made between 1947 and 1950 had flung the conventional constraints of painting so wide open that it no longer seemed capable of sustaining its disciplinary boundaries: “with the huge canvas placed upon the floor, thus making it difficult for the artist to see the whole or any extended section of ‘parts,’ Pollock could truthfully say that he was ‘in’ his work.”5 He was also on his work. He walked and knelt on the canvas and put out his cigarettes on it. Handprints and footprints are interwoven with the dripping trails of paint, as are an array of things normally kept outside the space of a painting: coins, matches, buttons, nails, tacks, sand and bugs all found their way into the densely layered oil and enamel. The canvas rectangle on the floor marked out a specially charged zone within the space of Pollock’s life, but it was also very much continuous with the rest of his life. It was a flat material surface on which (and against which) he acted, as if it were, in the words of Kirk Varnedoe, only “an extension of the physicality of the world, not a window onto anything else.”6

As Kaprow saw it, the primary consequence of this was that the edges of the painting began to appear as “an abrupt leaving off of the activity, which our imaginations continue outward indefinitely, as though refusing to accept the artificiality of an ‘ending.’”7 The key point is that in Pollock’s case this imaginative projection “outward indefinitely” was not pictorial: it had nothing to do with imagining the world of the image extending beyond the pictorial frame (journeying further into a represented landscape, for instance). Rather, it was the imagined possibility of the artistic activity (and the “medium” of that activity) extending indefinitely beyond the arbitrary shape of the canvas. If what is most interesting about Pollock’s painting is that he was “living on the canvas,” as Harold Rosenberg had argued in 1952,8 then it becomes conceivable that the artwork—that which is most meaningful about what the artist has made—has more to do with this concentrated kind of living than with the canvas artifact that is presented afterward. And if that is the case, then it seems that confining the scope of that activity to the space and materiality of oil on canvas is a limitation imposed by convention more than by necessity. In fact, according to Kaprow the logical next step beyond Pollock (and into a fuller artistic practice) was “to give up the making of paintings entirely—I mean the single flat rectangle or oval as we know it”9—and instead to push into the possibility of an art composed of living without the canvas.

Kaprow argued that those artists who were prepared to follow him into this relinquishing of traditional art materials and formats (as a painter himself he recognized the real sense of loss this might entail) would need to entirely resensitize themselves to the world around them. Those willing to lose their artistic lives must find them again in the experiences of everyday living:

Pollock, as I see him, left us at the point where we must become preoccupied with and even dazzled by the space and objects of our everyday life, either our bodies, clothes, rooms, or, if need be, the vastness of Forty-second Street. Not satisfied with the suggestion through paint of our senses, we shall utilize [as artistic media] the specific substances of sight, sound, movements, people, odors, touch. Objects of every sort are materials for the new art: paint, chairs, food, electric and neon lights, smoke, water, old socks, a dog, movies, a thousand other things that will be discovered by the present generation of artists.10

This is strongly reminiscent of Kandinsky’s epiphanic experiences, which similarly left him dazzled by the space and objects of his own everyday life—this cigar butt, trouser-button, disposable calendar page and so on (see chapter four)—but Kaprow’s response was to try to redefine artmaking around the cultivation of those experiences. The point was not simply to make artworks that were more about life; it was to make an art of life, or to conduct everyday life in such a way that it is meaningful as art. As far as Kaprow was concerned, the profoundest form of art is one that functions as a way of living a meaningful life (and thus it might not look like art all). Or conversely, it makes conspicuous the meanings of the lives we have already been living:

Not only will these bold creators show us, as if for the first time, the world we have always had about us but ignored, but they will disclose entirely unheard-of happenings and events, found in garbage cans, police files, hotel lobbies; seen in store windows and on the streets; and sensed in dreams and horrible accidents. An odor of crushed strawberries, a letter from a friend, or a billboard selling Drano; three taps on the front door, a scratch, a sigh, or a voice lecturing endlessly, a blinding staccato flash, a bowler hat—all will become materials for this new concrete art.11

To this end Kaprow theorized the “happening”—an intentionally initiated occurrence that engages the materials and activities of everyday life in such a way that they stand out as unusual, unexpected, salient. He distinguished happenings from theatrical events in the sense that they have no plot, no clear symbolism, no defined audience or institutional framing; they are improvisational, vulnerable to chance, unrepeatable and sometimes utterly mundane in tone and setting. A happening “might surprisingly turn out to be an affair that has all the inevitability of a well-ordered middle-class Thanksgiving dinner. . . . But it could [also] be like slipping on a banana peel, or going to heaven.”12 The most thoughtful of the artists involved (Kaprow later called them “un-artists”) wanted to dissociate these activities from the trappings of high “Art” but primarily for the sake of channeling the kind of critical self-awareness of art into everyday life: the happenings “worked” when they generated the sense that “here is something important.” In the happening “nothing obvious is sought and therefore nothing is won, except the certainty of a number of occurrences to which we are more than normally attentive.”13

Many of the earliest happenings were staged in the spaces of galleries or theaters: Kaprow’s first fully developed public happening was 18 Happenings in 6 Parts at the Reuben Gallery in New York in October 1959. At an appointed time audience members were ushered into the gallery and given programs that directed their participation. The space was divided into three makeshift rooms made of stretched plastic sheeting, in which a total of six artists each performed tightly scripted “scores” of root directions, including squeezing oranges, sweeping the floor, sitting on a chair, scaling a ladder, shouting a political slogan, giving a concert on toy instruments and so on. There was no plot or characterization of the performers, only the “happenings” of human activity in relation to the activities of those who constituted the audience. The logic of the happenings, however, almost immediately pushed them outside of institutional art spaces and away from self-conscious audiences. As Kristine Stiles puts it, “Happenings were meant to destroy the nonparticipatory gaze, shatter the proscenium [of the theatrical stage], and involve an audience in the creation of a work of art.”14 This implied that the art activity must become as open and as decentralized as possible and should unfold within the common spaces of daily life: in laundromats, subway trains, Times Square, during friendly introductions at a party, while sitting alone in front of a mirror.15 They could be as disruptive as banging pots and pans or as subtle as carefully controlling one’s own breathing.

Part of Kaprow’s argument is that the kind of attentiveness we devote to art objects should (primarily) be focused toward the rest of life. When we approach a painting in a museum—anything from Courbet’s Burial to Pollock’s Cathedral—we do so with a structure of expectations that is specifically ordered toward having a meaning-full encounter. Whatever forms this takes—anything from careful philosophical reflection to delighting in surprising formal relationships—we expect artworks to deliver meaningful experience. These expectations are carefully managed and sustained by fairly complex efforts to isolate art objects in spaces specifically set aside for this kind of focused attention. A painted object is installed at eye level under controlled lighting; the gallery structure is constructed, arranged and colored to maximize the visual impact of this object; museum staff maintain open hours for visitors to spend time with such objects—all of these are intervals of time and space set aside for practicing meaningful encounter and “contemplation.” And it works: endless discourse flows from the meaningful encounters that people have in front of paintings. Kaprow’s complaint, however, is that the intervals of human life for which we reserve this kind of expectation are too narrow and too insulated: “with the emergence of the picture shop and the museum in the last two centuries as a direct consequence of art’s separation from society, art came to mean a dream world, cut off from real life and capable of only indirect reference to the existence most people knew.”16 His goal was not to abolish these institutions as much as it was to instigate experiences that were, in the words of Jeff Kelley, capable of “reversing the signposts that mark the crossroads between art and life,” redirecting our expectations for rich aesthetic meaning away from the specialized museum space toward the particular places and mundane events of daily human experience.17

If Kaprow was to turn away from “Art” as providing the primary points of reference for the happenings, then he first had to recognize that “there were abundant alternatives in everyday life routines: brushing your teeth, getting on a bus, washing dinner dishes, asking for the time, dressing in front of a mirror, telephoning a friend, squeezing oranges. Instead of making an objective image or occurrence to be seen by someone else, it was a matter of doing something to experience it yourself.” It was a matter of “doing life, consciously.”18 What distinguished everyday toothbrushing from toothbrushing-as-art was therefore the level of consciousness with which one attended to the experience of living in this or that way. And of course committing to “doing life consciously” in this way renders everyday life as fairly strange: “paying attention changes the thing attended to” in the sense that it “exaggerates the normally unattended aspects of everyday life . . . and frustrates the obvious ones.”19 But this is not strangeness for the sake of being strange; the point was to enrich and deepen our alertness to the structure of the lives we live together. For example, Bill remembers participating in one of Kaprow’s happenings in Portland, Oregon, in the early 1970s in which participants were invited, in pairs, to take mirrors out into the city to learn to see it with fresh (and multiple) eyes, while at the same time learning to see themselves seeing.

The resulting strangeness inevitably had social and ethical implications, and for Kaprow these implications emerged particularly with respect to the powerful shaping influence of mass media on the American social imaginary:

Happenings are moral activity, if only by implication. Moral intelligence, in contrast to moralism or sermonizing, comes alive in a field of pressing alternatives. . . . The Happenings in their various modes resemble the best efforts of contemporary inquiry into identity and meaning, for they take their stand amid the modern information deluge. In the face of such a plethora of choices, they may be among the most responsible acts of our time.20

As Kaprow saw it, “the modern information deluge” creates profound challenges to living a life that is attentive, reflective and responsible. With increasing speed and efficiency we have grown accustomed to reducing things and moments to quickly consumable data, entertainment or merchandise, which are all available “choices” in an inundating flow of information. The moral drive of the happenings was to interrupt and slow down one’s experience of life in ways that strategically resisted any conversion into data, entertainment or merchandise. And for Kaprow, if it was really going to function as moral activity, it had to deal with the life one is actually living: “the spirit and body of our work today is on our TV screens and in our vitamin pills.”21

However, all of this was also theologically charged. The life-affirming “moral activity” of the happenings intrinsically carries questions of theological cosmology, anthropology and eschatology. And Kaprow seems to have been quite conscious of these questions; references to religious and theological (particularly Christian) ideas appear in his writings with surprising frequency, generally as components of unresolved problems and questions. Kaprow’s family was Jewish, but he spent most of his youth away from home and was relatively disengaged from his family’s faith. In the late 1970s he began practicing Zen Buddhism, but in the intervening years, from the 1950s into the 1970s (during the most significant formulation of the happenings), his theological views seem to have been those of someone suspicious of religious codification and organization but genuinely seeking the understanding and insights religious traditions might offer. Kaprow was relatively well acquainted with Christian theology, though he was critical of the midcentury American church (at least in its popular manifestations). His views during this period are perhaps best summarized in his 1963 essay “Impurity” (in a passage discussing Mondrian’s theological beliefs):

To the extent that philosophy and theology aspire to be wisdom as well as analysis or description, we may expect to be enlightened when we have understood what is said and when we have modified our existence according to the precepts learned. We like to assume that philosophers are wise from their philosophy and that those who are holy are personally acquainted with the spirit they preach. These assumptions may be valid, but the preparation and the enlightenment, however they may be connected, are still two different things.22

To the extent that the happenings were “moral activity,” they were also spiritual activity—sites in which he attempted to attentively modify his existence and to work out how his own theological “preparation” and “enlightenment” might be more integrally connected amid, or in the face of, the modern information deluge.

Kaprow studied art history at Columbia University under Meyer Schapiro, completing a master’s thesis on Mondrian in 1952, and he quickly received a teaching position at Rutgers University. While teaching art history at Rutgers in 1957 (the year prior to the publication of his essay on Jackson Pollock), Kaprow attended a musical composition class at the New School for Social Research taught by musician and composer John Cage (1912–1992)—a class that would prove to be transformative.

Cage was interested in testing the distinction between “music” (which exhibits some kind of structured intelligibility) and “noise” (unintelligible or unwanted happenstance). In questioning this distinction he began borrowing some key insights from Eastern philosophy: “Quite a lot of people in India feel that music is continuous; it is only we who turn away.”23 Indeed, this notion provided the basis for one of the central ideas that Kaprow would learn from Cage: the fundamental difference between music and noise is not in the qualities of the sounds but in the attentiveness of the listener.

Many of Cage’s most salient insights into the nature of music emerge from his investigations into silence. In 1951 he visited an anechoic chamber at Harvard University in an effort to hear true and total silence. Upon exiting the chamber Cage reported that (against his expectations) he actually heard two sustained sounds while inside—one high and one low—which he was informed were his eardrums picking up the activity of his nervous system (high) and the circulation of his blood (low). This was an enormous revelation to the musician: absolute silence is absolutely elusive because there is always the sound of hearing itself, the sound of one’s own body supporting the listening, the sound of being here. Eventually Cage would see that the same observation might be made on a more massive social scale, with respect to the social body: “The sound experience which I prefer to all others is the experience of silence. And the silence almost everywhere in the world now is traffic.”24 For Cage the definition of “silence” flipped around: it cannot be a total absence of sound but rather only a silencing of oneself in order to really hear the sounds that the world is (always) giving and to hear the systems that are (always) operating in the “background”—whether those systems are physiological, economic or otherwise.

The experience in the Harvard chamber propelled Cage into his most infamous exploration of silence: his 4′33″ (1952), a piano performance in three movements lasting a total of four minutes and thirty-three seconds. The work was first performed on August 29, 1952, by the remarkable young pianist David Tudor at the Maverick Concert Hall in Woodstock, New York. After walking onto the stage and taking his seat at the piano, Tudor (per Cage’s instructions) initiated the beginning of each movement by closing the lid of the piano keyboard and the end of each movement by opening it. The three movements were assigned specific durations of musical rest—30″, 2′23″ and 1′40″—which Tudor timed using a stopwatch while depressing a different foot pedal throughout each of the movements. Not a single note was played on the piano for the entirety of the work. When Tudor finally opened the keyboard lid for the final time and stood up from the piano, the already frustrated audience burst into “a hell of a lot of uproar,” “infuriated” and “dismayed” according to those recalling their experience of the event.25 Cage certainly expected this kind of response, but he believed that there were much deeper implications available to those willing to give it further consideration: “I knew it would be taken as a joke and a renunciation of work, whereas I also knew that if it was done it would be the highest form of work.”26 As he consistently maintained, this work emerged with the conviction that it was a good and meaningful thing to do: “I have never gratuitously done anything for shock, though what I have found necessary to do I have carried out, occasionally and only after struggles of conscience, even if it involved actions apparently outside the ‘boundaries of art.’”27

No notes were played on the piano for the duration of 4′33″, but the music hall was in fact full of sounds. The Maverick Concert Hall is a rustic theater in which the back wall (opposite the stage) opens out into a surrounding forest. “After the first embarrassed shuffling of feet,” writes Tony Godfrey, “the audience, if they were prepared to, could detect far-off bird songs or cars traveling or wood creaking—silence was surprisingly noisy.”28 Or rather, silence was surprisingly full of sounds that might be experienced as musical. And it seems this was exactly the point: an attentive audience had gathered here to hear music, but the artwork they were offered withheld everything they expected to hear (a carefully composed series of vibrations on the piano’s strings) and instead gave the temporal space of the performance over entirely to the sounds of the hall itself and its surroundings. Presumably this was the music the audience was being prompted to attend to.

The outrage that ensued was the result of (understandably) frustrated expectations. The concertgoers who had gathered at the Maverick that August evening were there to support the Benefit Artists Welfare Fund; these were people who generally supported modernist music.29 But even they felt they had been jilted, refused the kind of sonic experience they had come for. They were poised to hear innovative and challenging musical performances, and they found themselves (at least for four and a half minutes) given only the sounds of their own listening and the sounds that had been going unnoticed all around them. In addition to the ambient sounds of the concert hall, it was thus also the structure of the audience’s (denied) expectations—and the cultural norms that support them—that was exhibited in plain sight.

The fact that Cage regarded this as “the highest form of work” obviously has nothing to do with its deployment of skill or artistic genius (or even cleverness), nor with any construction of narrative, symbol or formal compositional complexity. Rather, his regard for the importance of this work derives from his overriding belief that art is whatever intentional human activity functions as “a means of converting the mind, turning it around, so that it moves away from itself out to the rest of the world.”30 The highest form of art is whatever discloses the sheer givenness of experience itself and turns one toward the world with a deep sense of meaning and gratitude. For Cage this kind of art belonged to “a purposeful purposelessness or a purposeful play” that is oriented toward “an affirmation of life—not an attempt to bring order out of chaos nor to suggest improvements in creation, but simply a way of waking us up to the very life we’re living, which is so excellent once one gets one’s mind and one’s desires out of its way and lets it act of its own accord.”31

Cage’s experiments in music had extensive influence in the visual arts. Kaprow, for instance, identified the implications for his own artistic practice: “As Cage brought the chancy and noisy world into the concert hall (following Duchamp, who did the same in the art gallery), a next step was simply to move right out into that uncertain world and forget the framing devices of concert hall, gallery, stage, and so forth.”32 And thus the happenings. “But here,” says Kaprow, “is the most valuable part of John Cage’s innovations in music: experimental music, or any experimental art of our time, can be an introduction to right living; and after that introduction art can be bypassed for the main course.”33 If the goodness of art is in its ability to turn us toward a fuller living of life, then of course art could not be the end in itself. In 1988, in a conversation with composer William Duckworth, Cage affirmed the extent to which his 4′33″ had indeed become a way of life: “No day goes by without my making use of that piece in my life and in my work. I listen to it every day. . . . I don’t sit down to do it. I turn my attention toward it. I realize that it’s going on continuously. More than anything, it is the source of my enjoyment of life.”34

Kaprow helpfully identifies the underlying idea: “In Cage’s cosmology (informed by Asiatic philosophy) the real world was perfect, if we could only hear it, see it, understand it. If we couldn’t, that was because our senses were closed and our minds were filled with preconceptions.”35 Kaprow almost gets it right, but designating the world as “perfect” somewhat muddles the issue; the point is rather that Cage regarded the world as inherently good—good simply in that it is and good in that we have experience of it—if we could only hear it, see it, receive it as the perpetual, gratuitous gift that it is. The world is inexplicably and gratuitously “given” at all moments, full of sounds (even if only the sound of the blood supply flowing through one’s own eardrums), which are profoundly meaningful and surprisingly beautiful “music” if truly attended to.

And it is precisely there that Cage’s ethic of “right living” comes into view, as well as (by implication) the possibility of wrong living—of being asleep to the life one has been given, of having one’s mind and desires very much in the way of experiencing the world in its abundance. Cage occasionally vocalized his concerns about how prevalent he believed the collapsed life was:

Many people in our society now go around the streets and in the buses and so forth playing radios with earphones on and they don’t hear the world around them. They hear only . . . whatever it is they’ve chosen to hear. I can’t understand why they cut themselves off from that rich experience which is free. I think this is the beginning of music, and I think that the end of music may very well be in those record collections.36

Indeed, like Kaprow, Cage worried that mass media might be generally threatening to “right living” to the extent that it deadens our capacities for attentiveness, gratitude and ultimately joy.37

Thus, as one digs into Cage’s aesthetics, one finds an ethics, which is itself rooted in an essentially religious ontology. On the one hand, this ontology is strongly influenced by Zen-Buddhist practices of mindfulness, which Cage discovered in his thirties. On the other hand, these Buddhist principles were appropriated into a particularly American religious sensibility that was more deeply rooted in Protestant Christianity—both that of his own upbringing and that of the broader culture in which he was raised. Whereas the Buddhist notion is to move out from oneself in order to “lose” oneself (anatta), the effect that Cage (and many of the artists he influenced) most valued was to “find” himself experiencing the sheer good givenness of being in all of its astonishing particularity. The silent mindfulness that directed Cage’s work was oriented toward personal experiences that issue in fuller and more thankful ways of receiving the world as it is.

Interestingly, Cage was a devout Protestant Christian as a young man—to the point that he even considered “devoting my life to religion.”38 And he continued to think about his work in relation to Christian theology, even after leaving the church. For instance, he linked his love for the givenness of environmental sounds to Jesus’ admonition to “consider the lilies.” In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus urges those who hear him to reorient their affections:

I say to you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or what you will drink; nor about your body, what [clothes] you will put on. Is not life more than food and the body more than clothing? . . . Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow: they neither toil nor spin; and yet I say to you that even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these. (Mt 6:25-30 NKJV; cf. Lk 12:22-31)

For Cage, the sonic equivalent was to say that even Beethoven in all his glory could not compose sounds like those going on around us at every moment. Cage sought to quiet his own aesthetic “worry” for musical meaning and to instead receive the given sounds of the world as richly meaningful in themselves: “The work of the lilies is not to do something other than [be] themselves . . . and that, I think, could bring us back to silence, because silence also is not silent—it is full of activity.”39 Indeed, he believed that this conviction that “everything communicates,” even in silence, is in fact “very Christian.”40

Unfortunately the Christian churches that Cage attended as a young man were anemic institutions preoccupied with otherworldly sentimentalities. By his own recounting:

When I was growing up, church and Sunday School became devoid of anything one needed. . . . I was almost forty years old before I discovered what I needed—in Oriental thought. . . . I was starved—I was thirsty. These things had all been in the Protestant Church, but they had been there in a form in which I couldn’t use them. Jesus saying, “Leave thy Father and Mother,” meant “leave whatever is closest to you.”41 (cf. Mt 19:29)

It is precisely on this point that Rookmaaker (and other Christians) should have found great sympathy with Cage. The kind of escapist Protestantism that left him spiritually starving and thirsty is exactly the same “gnostic” religiosity that Rookmaaker objected to and sought to correct. And though Cage didn’t quite say it in these terms, the currents of his work were oriented toward the practical recovery of a more thoroughgoing creational theology—one that sought to return to all the “closest” aspects of creaturely existence and to become more fully conscious of and thankful for the gratuitous goodness and givenness of the world. This was the theological orientation that Cage recognized as latent in the Protestant church (though too often warped into unusable forms), and this is what might have resonated deeply with Rookmaaker had his conventional theory of art and the sheer momentum of his narrative not precluded him from recognizing it. Sadly, he utterly misinterpreted and underappreciated Cage’s work, regarding it as the epitome of “meaningless and essentially inhuman freedom since there is no possibility of communication.”42 And because he reduced the function of the artwork to the “possibility of communication,” he entirely missed the point: “As such it means death and absolute alienation.”43 Obviously we wish to argue almost the exact inverse of that position: Cage’s primary concern was with life and deliberate reconnection.

While he was a student at the experimental Black Mountain College in North Carolina, Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008) met John Cage in 1951, and according to Rauschenberg it was obvious that they “were soul mates right from the very beginning, philosophically or spiritually.”44 Their mutual affinity included strong sensitivities to the spiritual implications of artmaking, tempered by a similar dissatisfaction with the American appropriation of the Christian gospel.

Throughout his youth, Rauschenberg’s family belonged to Sixth Street Church of Christ, a strict fundamentalist congregation in Port Arthur, Texas. His mother, Dora, was especially devout and urged her son to grow in the faith; he attended church and Sunday school every week and went to Bible study classes during summer breaks. By the time he was thirteen, young Milton (he later changed his name to “Bob” as he began pursuing a career in art) had set his heart on becoming a pastor, though experiences in his church would soon discourage him from this. “The Church of Christ made the Baptists look like Episcopalians,” Rauschenberg later joked. “There wasn’t an idea you could have that couldn’t lead somebody else astray.”45 A particular point of contention was dancing, which was one of Rauschenberg’s great joys but was adamantly forbidden by his family’s church. As Elizabeth Richards puts it, he gradually “became disillusioned with a church that, as he felt, restrained its community from enjoying life.”46 After moving away from home he continued to attend a variety of churches into his mid-twenties but eventually abandoned the church altogether. He later confessed, “Giving that up was a major change in my life.”47 Even so, the split was not absolute: Richards notes that his “rejection of organized religion did not dictate any rejection of spirituality and, in fact, his art often incorporated aspects of ritual and ceremony that recall his religious upbringing.”48

Rauschenberg’s first solo exhibition was at the well-known Betty Parsons Gallery in New York City. Parsons represented the major figures of American abstract expressionism—including Pollock, Still, Rothko, Reinhardt and Newman—and yet she unexpectedly offered the twenty-five-year-old Rauschenberg an exhibition based on a handful of paintings he brought into her gallery. The show opened in May 1951 in the smaller of Parsons’s two exhibition rooms (the larger main room featured the more established Walter Tandy Murch) and consisted of thirteen oil-and-collage paintings. Rauschenberg’s titling of the works was curious: some of the titles followed the abstract expressionist convention of numbering (Untitled No. 1, No. 2 and so on), while others incorporated weighty poetic or religious references, including Eden (c. 1950), Trinity (c. 1949–1950), and Crucifixion and Reflection (c. 1950).49 The exhibition received little attention, and most of the works were subsequently destroyed, lost or painted over—one of only a handful that remain is Mother of God (c. 1950).

The “figure” of the Mother of God is an irregular circular white form whose center is stationed two-thirds of the way up the surface of the painting, precisely where in a traditional icon of the Mother and Child one would generally find either Mary’s face (and halo) or her torso (womb). Surrounding this form are collaged portions of twenty-two city maps that have been cut or torn from Rand McNally road atlases: the yellowed pages simultaneously evoke the gold-leafed space of an icon and the earthly landscape backdrop of a Renaissance Madonna (with a topographical twist). The bottom fifth of the painting is a kind of parapet50 or predella51 painted in the same white paint as the central circular figure, and along the bottommost edge of the panel a strip of silver paint (which has dulled and darkened over the years) appears like a leaden weight in contrast to the buoyancy of the white orb. In the lower right corner of the white parapet a torn fragment from a newspaper (about four inches wide) bears the words of a book blurb: “‘An invaluable spiritual road map . . . As simple and fundamental as life itself’—Catholic Review” (ellipsis original). The singularity of the blurb seems at odds with the multiplicity (even confusion) of the maps: they exert interpretive pressure on one another such that this “spiritual road map” seems “to function simultaneously as an ironic joke and as an utterly sincere message,” as one critic has put it.52 And Rauschenberg himself underscores this ambiguity: “It’s made of maps. So you follow one road or another and you’re gonna get there.”53

The “there” to which these earthly roads point is presumably the circular white Theotokos in the center. Branden Joseph argues that “by keeping collage from the center of the painting, Rauschenberg . . . signified that the white was at once in the world and to be understood as somehow separate from it. The white would thereby seem to be symbolic of the divine.” Joseph thus reads the work as seriously pondering the possibility of incarnation: “Like the body of the Virgin Mary, Rauschenberg’s Mother of God serves as a material or bodily vessel for the manifestation of the divine.”54 In this vein, Susan Davidson sees the circular form as “alluding to pregnancy” and suggestive of a (God-bearing) womb.55 That may be, but especially given Rauschenberg’s strict religious upbringing, the aniconic character of the work seems to reveal distinctly Protestant inclinations. In a conversation with Rauschenberg about this painting in 1999 David Ross referred to this white space as “void,” which Rauschenberg rejected: “There’s nothing missing there. . . . It’s full.”56 His withholding of figurative imagery was apparently in the service of figuring some kind of fullness (rather than simply negation).

In the months following his exhibition at Betty Parsons’s gallery, the fecund white womb in the center of Mother of God seems to have expanded to encompass an entire series of canvases known as the White Paintings (1951). These large canvases were painted with even layers of flat white house paint applied with a roller, creating uniform white fields with as little surface variation as possible.57 Each painting in the series consisted of a different number of adjoined panels: there are one-, two-, three-, four- and seven-panel iterations—all combinations that ostensibly were meant to have sacred connotations.58 According to the artist, his decision to terminate the series with a heptaptych was due to the idea that “seven was infinity.”59

In fact these seemingly blank paintings emerged at the height of what Rauschenberg later called a “short-lived religious period.”60 In mid-October 1951, less than five months after his first show, he wrote an impassioned letter to Parsons telling her about these new paintings.61 His opening lines identify the spiritual impulses behind these works: “I have since putting on shoes . . . felt that my head and heart move through something quite different than the hot dust the earth threw at me. The results are a group of paintings that I consider almost an emergency.” His description of the paintings is especially evocative: “They are large white (1 white as 1 GOD) canvases organized and selected with the experience of time and presented with the innocence of a virgin.” This analogizing of the singularity of the white color with the unity of God—which manifests itself across a multiplicity of panels that presumably denote an “experience of time”—gives way to a series of enigmas: these paintings articulate the “body of an organic silence, the restriction and freedom of absence, the plastic fullness of nothing, the point a circle begins and ends.” Ultimately he claimed that “they are a natural response to the current pressures of the faithless and a promoter of intuitional optimism. It is completely irrelevant that I am making them—Today is their creater [sic].” In fact he felt such urgency about the relevance of these works that he declared himself willing to “forfeit all rights to ever show again for their being given a chance to be considered for this year’s calendar.” Parsons declined.

Because they appeared in the early 1950s, Kaprow argued that “in the context of Abstract Expressionist noise and gesture,” these white paintings “suddenly brought us face to face with a numbing, devastating silence.”62 If indeed it could be said that the abstract expressionists “took to the white expanse of the canvas as Melville’s Ishmael took to the sea,”63 Rauschenberg’s paintings give us only the sheer expanse itself—or perhaps only the deathly whiteness of Melville’s monster.64 If these canvases do stand for a kind of silence, Rauschenberg apparently considered it a holy silence. In presenting these surfaces without any image, without any markings, without any “color” (in terms of occupying a discrete location on the color spectrum), he was effectively quieting painting down to an apophatic speechlessness. Their “blankness” was a gesturing toward the unrepresentable fullness of God (1 white as 1 GOD), “the plastic fullness of nothing [no-thing], the [unidentifiable] point a circle begins and ends.” The decision to subdivide this apophatic whiteness into a series of modular polyptych formats introduces a sense of temporality (“organized and selected with the experience of time”), but it also has the possible effect of “framing” the silence of the work in religious terms, redeploying formats traditionally associated with Christian altarpieces and manuscripts.65 These polyptychs present no holy visage or script; they only conduct silent vigil.

It is not difficult to see Cage’s 4′33″ and Rauschenberg’s White Paintings as interrelated investigations into “silence.” Cage openly associated the two works and in doing so assigned the precedence to Rauschenberg: “To Whom It May Concern: The white paintings came first; my silent piece came later.”66 In fact Cage would become one of the most influential interpreters of these canvases, construing them as surfaces hypersensitive to the visual phenomena around them in much the same way his 4′33″ was to auditory phenomena: “The white paintings were airports for the lights, shadows and particles”; they visually “caught whatever fell on them.”67 Adopting a different metaphor, Rauschenberg referred to them as “clocks”: if they were attended to with enough sensitivity it was possible “that you could read it, that you would know how many people were in the room, what time it was, and what the weather was like outside.”68 In other words, for Rauschenberg (and Cage) these paintings were not attempts to reduce painting to a state of aesthetic “purity” (as theorized by Greenberg) or sheer material “presences” (as theorized by the minimalists);69 rather, they were a means of visually “silencing” a series of art objects (ultimately an entire exhibition space)70 in order to receive and amplify the life going on in front of, around and behind them. As with Cage’s performance of musical rest, when these paintings fell silent they impelled the viewers’ interpretive efforts to shift toward whatever else was in the (social, physical, temporal) space they were standing in and (at least for the more self-reflective viewers) toward whatever structure of expectations might cause someone to feel scandalized by the silence.

Thus for Cage these paintings turned out to be utterly affirmative of the tangible, generous thisness of the world:

Having made the empty canvases (A canvas is never empty.), Rauschenberg became the giver of gifts. Gifts, unexpected and unnecessary, are ways of saying Yes to how it is, a holiday. The gifts he gives are not picked up in distant lands but are things we already have . . . and so we are converted to the enjoyment of our possessions. Converted from what? From wanting what we don’t have, art as pained struggle.71

The upshot of saying yes to the world as it presents itself is that we begin to find that “beauty is now underfoot wherever we take the trouble to look. (This is an American discovery.)”72

Rauschenberg was quick to see the implications of experiencing the white paintings in this way. When painting is brought close to visual silence, the result is not an experience of absence or an ongoing meditation on “the void”; rather, it elicits a finer “listening” to what is present and provokes heightened sensitivities to the sheer miraculous hereness of everything. As Rauschenberg would later say, the series is “not a negation; it’s a celebration.”73 As far as painting is concerned (or any aspect of human experience), there is no possibility of void; all of this is simply and inexplicably “given.” Thus, whatever apophasis originally motivated the White Paintings becomes inverted: once we truly quiet ourselves down (whether in painting or everyday life), what we experience is not (only) the stillness of God but the astonishing presence of the world God gives. As in all great apophatic thought, holy silence is not simply about attuning oneself to the Fullness that outstrips human sight, speech and thought; it also leaves one differently attuned to the fullness of what is seeable, speakable, thinkable. However we conceptualize that Fullness (or No-thingness) that precedes and sustains all being, all of this appears within it and is given by it.

The further implication is that bringing painting to this level of silence does not give us any simple essence of “painting” as much as it reveals the manifold human activity that composes and supports the practices of painting. Like Cage’s silent work, the hypersensitivity of Rauschenberg’s white canvases points us not only toward the immediate environment (and the beauty that is everywhere underfoot) but also to the cultural worlds in which these canvases are produced, handled, exhibited and discussed—and in which they become intelligible. Rauschenberg stated the matter bluntly: “I stretched the canvas—I knew what it was—it’s a piece of cloth. And after you recognize that the canvas you’re painting on is simply another rag then it doesn’t matter whether you use stuffed chickens or electric light bulbs or pure forms.”74 The hyperbolic use of the word rag here is often misinterpreted. This was not meant as a flippant belittling of painting, as if the canvas serves no meaningful function beyond that of a rag (absorbing oil). Rather, Rauschenberg was describing the recognition that the materials of painting—cloth, wood, nails, pigment, refined oil, solvents, etc.—are products of manufacturing and cultural custom that have been taken out of everyday commerce (removed from a range of other possible functions) and used specifically for the discourse and commerce of art. But once recognized as such, why would artists limit themselves to these materials? The conventions of artistic medium that distinguish the cloth of the artist’s canvas from the cloth of the pants he is wearing began to appear to Rauschenberg as increasingly arbitrary and in fact preventative to an art more fully engaged in the dense meanings of the lives we are living—perhaps the pant leg needed to go into the painting as well. And for that matter, why not also the taxidermies, light bulbs, drapes, scraps of furniture, postage and “pure forms” that structured the spaces of daily life? Indeed, suddenly the entire field of his immediate surroundings became full of artistic media, and it became increasingly obvious that “there are very few things that happen in my daily life that have to do with turpentine, oil, and pigments.”75 In some ways Rauschenberg’s work becomes a counterpoint to Kaprow’s extrapolation of Pollock: whereas Kaprow discarded the canvas and paint for the sake of making art of the rest of life, Rauschenberg sought to bring the rest of life back into the domain of canvas and paint.

This shift in Rauschenberg’s thinking might be clearly encapsulated in the transition from the triptych White Painting (1951) to Collection (1954). The two paintings are of similar size (72 × 108 in. and 80 × 96 in., respectively) and share the same triptych format, but their materiality is radically different. The three vertical panels of the latter “painting” are traversed by layered bands of paint, newspapers, pieces of fabric, pictures torn out of books and a variety of other materials.76 The surface functioned as an “airport” not only for lights, shadows and particles but also for the diverse materiality of the studio space in which the work was made, as well as the materiality of the urban spaces in which the studio was situated and by which the life of the studio was supported. Leo Steinberg famously argued that Rauschenberg’s picture plane “makes its symbolic allusion to hard surfaces such as tabletops, studio floors, charts, bulletin boards—any receptor surface on which objects are scattered, on which data is entered, on which information may be received, printed, impressed—whether coherently or in confusion. . . . Though they hung on the wall, the pictures kept referring back to the horizontals on which we walk and sit, work and sleep.”77 And thus we are no longer oriented to look “into” the artwork as though it were a pictorial window;78 instead we are faced with a surface on which appears the stuff of life that was normally bracketed out of the experience of looking at art. Not only paint but also the tubes and cans it was packaged in, the mass-distributed newspapers and magazines read prior to getting to work,79 the art textbooks that funnel the pressures of history into the studio, the debris cast off from the daily consumption and (re)building of the city—all of it impinges upon the meaning of the work, and all of it is considered viable material for the construction of the work. This resulted in “paintings” that were exceedingly sculptural assemblages of recognizable everyday objects. Rasuchenberg called them “Combines.”

In the context of this study, a twofold point must be made: (1) for Rauschenberg these cultural “horizontals” of life included religious structures, and (2) the transition from the white paintings to the Combines involved (unavoidably) theological questions and difficulties. In 1952–1953 the white paintings were followed by paintings of glossy black oil over disheveled newspaper grounds,80 and then by a series of small iconic Elemental Paintings (c. 1953) consisting of a single accumulated material: dirt, clay, white lead paint, tissue paper or gold leaf.81 In the series of gold paintings, the surface of the gold leaf—a material traditionally used to signify the transcendent light of God—is mangled, distressed, tarnished and exceedingly delicate. When the transcendent reference in these icons is thus interrupted by the materiality and fragility of these surfaces, the (open) question is poignantly posed: Is the light of God visible even here, on the fragile surface of things? Presented in a gold-leafed frame, Rauschenberg’s landmark work Erased de Kooning (1953) raises similar questions through an iconic vernacular:82 the figuration of an otherwise “expressive” and “valuable” work of art has been almost entirely erased, revealing the fragile material-cultural givenness of the paper itself. Automobile Tire Print (1953) is a twenty-two-foot-long strip of adjoined papers on which Rauschenberg prompted Cage to “print” a single line of tire-text in black ink by driving over it with his Model A Ford. The work is presented as a (rarely completely extended) scroll, such that the tire print appears as a kind of sacred writ—Rauschenberg later referred to it as “a Tibetan prayer wheel.”83 Questions of spiritual anthropology seem to provide the thematic framework for works like Soles (or Souls—it is uncertain which spelling the artist intended, c. 1953) and Untitled (Cube in a Box) (c. 1953), both of which explore the idea of hidden inner substances within rough outer skins or casings. The rather extensive series of Elemental Sculptures (1953) takes up similar questions, repeatedly displaying tethered stones in ways that allegorically activate issues of heaviness and release.84

And the religious references proliferate through the Combines as well. Rauschenberg’s Untitled black painting with a funnel (c. 1955) is presented as a kind of figure: the open circular collar of a t-shirt positions a head relatively high in the field, and the fragment of a sleeve on the right-hand edge indicates a lifted hand. Nearly all of the collaged scraps of cloth and paper on the surface are painted over in flat black paint—one of the few portions that is not is a prayer card just to the right of the center of the painting that displays a reproduction of Carl Bloch’s Doubting Thomas (1881). Flurries of red, yellow, green and white paint have been slashed across the surface immediately below this image (the only place such color appears in the painting), which within the figure suggested by the cloth fragments correspond to the position of the wound in Christ’s side, as depicted in the prayer card. The painting’s surface subtly stands in for the wounded body of the resurrected Jesus, and as such the ball of twine placed in the funnel on the left side of the panel becomes doubly suggestive of incarnation (descending downward into the funnel) and ascension (being pulled upward out of the funnel). But if Rauschenberg is allegorizing the surface of the painting with the resurrected body of Christ, then he is also placing himself (and the viewer) in the position of the incredulous Thomas. It is a painting that powerfully articulates both a longing to touch and to see (Lk 24:39; cf. Lk 6:19) and the persistence and seeming ineluctability of doubt in the age of modernity (including the doubt that images, much less paintings, can any longer serve as vehicles for the kind of religious touching and seeing that we long for). Like much modern art, this is not a work of unbelief as much as it is of fragilized belief, one that is caught oscillating (or struggling) between doubt and belief.

In fact several of the Combines include materials and forms with strong religious associations: in the center of Untitled (1955) an obscured fragment of a tract asks in bold lettering “Does God Really Care?” Odalisk (1955–1958) includes a church donation envelope and a reproduction of the resurrected Christ addressing Mary Magdalene with the words Noli me tangere (“touch me not” from Jn 20:17). Pilgrim (1960) implies the spiritual assumption (or ascension) of a seated figure through a horizontal slit in the canvas. Franciscan II (1972) seems to depict a monk in prayer, evoking forms reminiscent of Jusepe de Ribera’s Saint Francis in Ecstasy (1642) or Édouard Manet’s Monk in Prayer (1865). Rauschenberg’s 1981 series of sculptures collectively titled Kabal American Zephyr is packed with religious references related to the problem of evil. See, for example, The Ancient Incident, Tree of Life Prune, The Proof of Darkness and The Parade of the Wicked Thoughts of the Priest. And so on.85

Hymnal (1955) provides a particularly interesting example because the crucified “hymnal” in the niche in the upper central portion of the work is actually a telephone book. In direct continuity with Rauschenberg’s theological trajectory, the work asks what it would mean to regard the phonebook, listing thousands of one’s unknown neighbors, as a kind of hymnal—an index (or chorus) of all those overlooked human images of God who surround us daily. And given the way that he has pierced this phonebook, we might even wonder about the association of the body of Christ with those innumerable names (lives). In a move that actually finds profound resonance in Christian theology, this utterly mundane phonebook is thus reframed as a text that is potentially as pertinent to one’s sense of sacredness in the world as all those hymnals that remain closed in the church pews six days out of the week. Unfortunately Rookmaaker flatly interpreted Rauschenberg’s work as asserting an essential arbitrariness and meaninglessness of the world: he saw these works as allegories of “a shabby world in which all things are of equal value, but no great values persist.”86 One wonders why a Reformed thinker like Rookmaaker shouldn’t instead have seen these as allegories of a world in which all seemingly “shabby” things are actually of astonishing value (if only we had the eyes to see).

One of the most theologically enigmatic yet pivotal of all twentieth-century artists is certainly Andy Warhol (1928–1987). The interpretations of his work are as diverse and divergent as possible, and yet almost every rendering of twentieth-century art history runs through him. In recent years, the religious and theological implications of his work have increasingly become an object of discussion and debate. In unpacking these implications, there are at least three crucial components that must be accounted for.

Warhol’s late works (1980s). In the last five or six years of his life (he died in February 1987), Warhol completed an astonishing number of paintings with overtly religious subject matter.87 These included paintings of both religious symbols—Crosses (1981–1982), Details of Renaissance Paintings (1984), etc.—and religious phrases—Repent and Sin No More (1985–1986), Heaven and Hell Are Just One Breath Away (1985–1986), etc. These paintings present many interpretive difficulties: Are they cynical, sincere or tragic? Does the repetition in these paintings denote cheap banality or ritual devotion? Most notable of Warhol’s late religious paintings is a series of paintings based on Leonardo da Vinci’s famous fresco of The Last Supper (1498)—a series that included more than one hundred paintings, drawings and silkscreen prints, many of which are enormous.

To take one example, The Last Supper (Dove) (1986) (plate 8) presents a line drawing of Leonardo’s famous painting overlaid with a price tag and the corporate logos of General Electric and Dove soap, all of which make cheap puns in the context of the Christian subject matter. GE is a cheeky play on the “light of the world” (Jn 1:9; 9:5). The inclusion of a soap brand creates a deflationary allusion to being “washed” in Christ by the Spirit (Eph 5:26; 1 Cor 6:11; Heb 10:22); the Dove insignia descends through the opening in the ceiling like the Holy Spirit at Pentecost;88 and the 59¢ label is suggestive of either Judas’s betrayal of Jesus for money (Mt 26:15) or a fairly crude reference to Eucharistic bread (assuming this label was taken from a box of crackers). And all of these are laid over a somewhat schmaltzy line-drawn rendition of Leonardo’s painting taken from a nineteenth-century encyclopedia.89 How is this convergence of images to be interpreted? Is this a devout religious painting attempting to “energize sacred subjects” from within the idiom of pop art? Is it a sharp critique of the American commodification of religion? A cynical mockery of Christian doctrine? An iconoclastic leveling of religious signs to the same order of mass-media simulacra that seizes all other signs? With Warhol the answers to such questions are almost never straightforward, but much rides on how we attempt to answer: the ways we interpret such works are entirely bound up with how we interpret the decades of Warhol’s work that preceded them.

Plate 8. Andy Warhol, The Last Supper (Dove), 1986

Warhol’s religious biography. Immediately after Warhol’s death, many stories and accounts surfaced attesting to a serious Christian faith that Warhol maintained throughout his life. Born to Slovakian immigrants, he grew up in a devoutly Byzantine Catholic home in Pittsburgh: his church followed the Ruthenian Rite, which is Roman Catholic but uses the liturgy and architectural customs of the Byzantine Eastern Orthodox Church. His mother, Julia Warhola, was devout throughout her life, and she lived with Andy in New York for twenty years until shortly before her death in 1972.90 According to Henry Geldzahler, “He and his mother went to mass all the time, not only on Sunday, and it was all very very real to him.”91 Warhol’s brother John similarly described the artist as “really religious, but he didn’t want people to know about that because [it was] private.”92 And circumstantial evidence supports this private devotion: his diaries are filled with references to his faith, as was his apartment décor; most notably, he kept a crucifix and a well-worn prayer book beside his bed.93 He evidently wore a cross on a chain around his neck, and according to his friend David Bourdon he regularly carried a pocket missal and rosary.94 But it was not entirely private: Warhol’s priest attested to the fact that he regularly attended Mass two or three times a week at his church, Saint Vincent Ferrer, and he donated and volunteered “with dedicated regularity” to serve meals to homeless New Yorkers at the Church of the Heavenly Rest on Thanksgiving, Christmas and Easter.95

One of the most influential accounts of Warhol’s faith has been the eulogy that art historian John Richardson gave at Warhol’s memorial service at Saint Patrick’s Cathedral on April 1, 1987. This eulogy was entirely devoted to illuminating “a side of his character that he hid from all but his closest friends: his spiritual side.” And according to Richardson this side is in fact “the key to the artist’s psyche”: when adequately accounted for, this “secret piety” reframes our interpretation of what Warhol was trying to do and “inevitably changes our perception of an artist who fooled the world into believing that his only obsessions were money, fame, glamor, and that he was cool to the point of callousness.” Specifically, he encourages at least two revisions: (1) Over against the image of Warhol as a dissolute bohemian (his Factory studio had a reputation for its debaucherous parties), Richardson asserted that “as a youth, he was withdrawn and reclusive, devout and celibate; and beneath the disingenuous public mask that is how he at the heart remained.” He maintained an “ability to remain uncorrupted, no matter what activities he chose to film, tape, or scrutinize.” And (2) over against the image of Warhol as a shallow and callous opportunist, he argues that “Andy’s detachment—the distance he established between the world and himself—was above all a matter of innocence and art,” an effort to construct a “revealing mirror” for a generation marked by spiritual searching, mass consumption and sociopolitical instability. With regard to both Warhol’s work and his public self-presentation, Richardson argued that we must “never take Andy at face value”—there was always more tactical shrewdness and religious seriousness going on behind the public persona.96

Warhol’s seminal works (1960s). Ultimately the argument about the theological content of Warhol’s religious works then finally turns on how we understand his most pivotal earlier works, particularly those made in the astonishingly prolific years of 1962–1964. What is primarily at issue is how we are to understand the trajectory of Warhol’s conceptual impulses, which appears to have been remarkably consistent throughout his career.97 This consistency is such that any discussion of the religious content of the late paintings is framed by and necessarily raises difficult questions about the (ir)religious content of the earlier work. Warhol’s artistic program trafficked in a consumerist superficiality that was shrewdly systematic, and thus the primary disagreements about his work depend on whether we interpret this superficiality as complicit or critical with regard to the consumerism they traffic in. In an influential essay from 1987 Thomas Crow offers a summary that still largely holds: “The debate over Warhol centers on whether his art fosters critical or subversive apprehension of mass culture and the power of the image as commodity [e.g., Rainer Crone], succumbs in an innocent but telling way to that numbing power [e.g., Carter Ratcliff], or exploits it cynically and meretriciously [e.g., Robert Hughes].”98 For his part, Crow poignantly argues for a modified version of the first of these views, claiming that although Warhol “grounded his art in the ubiquity of the packaged commodity,” he “produced his most powerful work by dramatizing the breakdown of commodity exchange.” More specifically, he believes that the critical power of Warhol’s work resides in its ability to create “instances in which the mass-produced image as the bearer of desires was exposed in its inadequacy by the reality of suffering and death.”99 We follow Crow in his reading of Warhol, but we want to advance the suggestion that Warhol’s criticality had a theological undergirding all the way through.

One way to understand Warhol’s early paintings is to see them as transposing traditional pictorial genres—still-life, landscape and portrait painting—into the visual culture of consumerism. His serial paintings of individual Campbell’s Soup Cans (1961) might be understood as still-life paintings of daily meals (something on the order of Chardin) but in an age of mass-produced meals and mass-produced imagery to market those meals. These paintings of individual cans quickly gave way to the idea that this kind of seriality could operate within a single canvas. In paintings like 200 Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962) the still life has become a landscape, filling the entire visual field with reiterated images of canned soup (the landscape of the grocery store aisle).100 Though Warhol’s earliest soup cans were hand-painted, by this point he had taken up a method of silkscreen printing that allowed for a quasi-mechanical painting process, quickly repeating the same image numerous times onto each canvas in a decisionless grid pattern (derived from the rectangular shape of the canvas). The resulting paintings were a low-tech mimicking of the mass production of the soups themselves, positioning these canvases simultaneously within the grand old traditions of painting and within the modern visual commerce of mechanically reproduced images. In 1962 he similarly devoted large canvases to gridded repetitions of 210 Coca-Cola Bottles, 192 One-Dollar Bills, 64 S&H Green Stamps and so on—any item that had the logic of mechanical reproduction already inscribed in it was a viable subject. At one level, all Warhol was doing was transcribing the logic of mass production into the traditional motifs and materials of “museum” painting. But the point was to produce a two-way critical distance: he placed the visual culture of mass production under the critical scrutiny of the museum, which in turn also problematized the insular space of the museum.

Warhol’s method achieved new conceptual range in the summer of 1962 when he discovered an emulsion process for transferring photographic images onto a silkscreen. This allowed him to shift his focus from mass-produced products (soup, soda, stamps) to mass-produced images (print, film, television)—the mechanically reproducible photographic media that are the lifeblood of consumerist visual culture. Once this phototransfer process was in place, Warhol quickly began running human images through his faux factory system.101 Most famously, he painted Marilyn Monroe in the weeks following her suicide in August 1962.

In Gold Marilyn Monroe (1962) the late movie star is presented in the visual vernacular of traditional icon painting. Like the Byzantine-derived icons that Warhol grew up with in his church in Pittsburgh, this image is resolutely flat. But the logic of this flatness is of a different order: whereas Byzantine flatness connotes transcendence (the icon is meant to both reveal and withhold the presence of the saint who stands in the light of God), Marilyn’s flatness is that of photographic duplication. The spray-painted metallic gold background does not denote the transcendent presence of God as much as a cheaply contrived glitz. This iconography has little to do with Monroe’s passage into a higher world but everything to do with her currency in the world of flattened consumable signs. This is the presentation of a (nearly instant) relic of celebrity media, venerated through the rituals of mass distribution. Nevertheless, there is a serious invocation of the holy going on in this painting: in Christian thought the woman pictured here bears and discloses the image of God as a human person. The religious trappings of this icon thus become doubly difficult: this is a profane “holy” image of a mass-produced photograph of a holy image. The critical question of the work cuts toward the function of the photograph in the middle of that equation: Has our use of this device had much of anything to do with love of God or love of neighbor?

As an individual unit—as it might appear on a magazine page or movie poster, for instance102—this photographic image of Marilyn’s ambiguously seductive half-smile maintains some of its visual currency, allowing the viewer to gaze upon “her” in admiration, erotic longing, jealousy, resentment or whatever. But when Warhol repeatedly prints the image, accumulating dozens of Marilyns on a single surface, the mediating mechanism becomes conspicuous. With a garish “lipstick-and-peroxide palette”103 Warhol repeated Marilyn over and over and over and over and over. Jonathan Fineberg calls it an “anaesthetizing repetition.”104 This is dramatized in Marilyn Diptych (1962), where we are given fifty Marilyns in one painting: half in bright saccharine colors and half in a ghostly black-on-white. As the singular publicity headshot is diffused into grids of reiterated faces, the haunting suggestion deepens: indeed, “Marilyn Monroe” is (only) a commodity. Certainly there was a Norma Jeane somewhere behind the photographic curtain, but the only “Marilyn” we know was (and is, even in her death) a mass-produced image packaged in a variety of sizes and formats devised for public consumption. As Thierry de Duve points out, the disquieting reminder in Warhol’s work is that “to be a star is to be a blank screen . . . a blank screen for the projection of spectators’ phantasmas, dreams, and desires.”105 Warhol’s pseudomechanical repetitions are high-art (low-tech) parodies of the mass distribution apparatus that makes this kind of consumption of human images possible. These portraits are faux celebrations of “celebrity,” apparitions of “glamor rooted in despair.”106 Along with Michael Fried, we find ourselves deeply moved by these “beautiful, vulgar, heart-breaking icons of Marilyn Monroe.”107

At the same time that Warhol was making these paintings, he was fashioning his own public persona to support and complicate their reception. In a series of obviously disingenuous statements, Warhol claimed, “I don’t feel I’m representing the main sex symbols of our time. . . . I just see Monroe as just another person. As for whether it’s symbolical to paint Monroe in such violent colors: it’s beauty, and she’s beautiful and if something’s beautiful it’s pretty colors, that’s all. Or something.”108 In fact this persona seems to have been specifically designed to deflect and defer the sharp criticality of his artworks, allowing them to continue circulating within celebrity culture.109 Diametrically opposite of Kaprow and Cage, Warhol positioned himself as (and publically performed the life of) the inundated consumer:110

I had this routine of painting with rock and roll blasting the same song, a 45 rpm, over and over all day long. . . . I’d also have the radio blasting opera, and the TV picture on (but not the sound)—and if all that didn’t clear enough out of my mind, I’d open a magazine, put it beside me, and half read an article while I painted. The works I was most satisfied with were the cold “no comment” paintings.111

Hal Foster argues that the amalgam of Warhol’s artworks and persona generated a critique of commercialized spectacle from inside of it. Rather than resorting to withdrawal or direct confrontation one might become more centralized within the spectacle (which Warhol certainly did): “If you enter it totally, you might expose it; you might reveal its automatism, even its autism, through your own excessive example.”112 And thus Foster sees Warhol as deploying a kind of “strategic nihilism”113 for the sake of amplifying aspects of consumer culture that already had a latent nihilist logic at work in them.114 According to Warhol, the strategy was to make the “signage” of consumer culture conspicuous: “Once you ‘got’ Pop, you could never see a sign the same way again. And once you thought Pop, you could never see America the same way again. The moment you label something, you take a step—I mean, you can never go back again to seeing it unlabeled.”115 We might say that Warhol’s work enacted a labeling of the labeling, critically marking spectacle as spectacle. This marking was generally oriented toward (1) interrupting the processes of mass-media culture that he considered unethical and idolatrous and (2) facilitating greater self-reflection about the forms of social life we are living. In a statement that could have been written by Cage or Kaprow, in 1966 Warhol gave an uncharacteristically frank explanation of his work: “Few people have seen my films or paintings, but perhaps those few will become more aware of living by being made to think about themselves. People need to be made aware of the need to work at learning how to live because life is so quick and sometimes it goes away too quickly.”116

All of this, we argue, is grounded in Warhol’s theological imagination. One way to frame this argument is to show (as many art historians have) that Warhol’s work is twentieth-century vanitas painting. The seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Dutch and Flemish traditions of vanitas still-life painting engaged and celebrated sensual pleasure, depicting objects that are pleasing to the senses—fruit, flowers, musical instruments—each rendered with rich painterly detail. At the same time, these paintings were also about the inevitability of loss: intermingled with these objects of pleasure are signs of decay—a flower has begun to wilt; the fruit is beginning to turn brown; flies and ants have begun to feed. To drive the point home, painters sometimes included a human skull among the items portrayed: the human being (in body, heart and mind) is itself full of both goodness and decay. Derived from the Latin translation of Ecclesiastes 1:2—“vanitas vanitatum omnia vanitas [vanity of vanities; all is vanity]”—the term identifies this painting tradition as a meditation on ephemerality. In English vanity has accumulated more negative moral associations than the original Hebrew intended; a closer translation would emphasize the fragility and delicacy of the world: “breath, breath; all is breath.” All things are to be received with delight and thanksgiving but, the paintings say, beware: a life devoted to grasping, possessing and controlling pleasures is ultimately a vain pursuit (akin to holding one’s breath). The driving question of both Ecclesiastes and vanitas painting thus remains: What is it to live a truly beautiful life once one recognizes the passing of all things and truly comes to face one’s own memento mori (“remember that you must die”)?

The Dutch vanitas tradition is perhaps most concisely summarized in David Bailly’s (1584–1657) Self-Portrait with Vanitas Symbols (1651) (fig. 7.1). The youthful artist holds a portrait of himself as an old man, surrounded by a virtual catalog of symbols of human frailty and mortality: flowers, bubbles, a snuffed candle, a tipped wineglass, a human skull. This painting, however, was made when Bailly was sixty-six or sixty-seven years old. The young man sitting at the table is a memory (a phantom) of himself at the beginning of his career, whereas it is actually the portrait that the young man is holding—the painting within the painting—that depicts the artist at the time the work was made. And it portrays someone who had suffered great loss: art historians conjecture that the oval portrait of the young woman immediately next to the oval portrait of the artist (and perhaps the ghostly drawing on the back wall) is the artist’s wife, Agneta, who had (as best we can tell) just died of the plague. Bailly’s painting is everywhere riddled with beauty and death intermingled.

Figure 7.1. David Bailly, Self-Portrait with Vanitas Symbols, 1651

This finds profound resonance in Warhol’s work. Not only were the subjects of his paintings consistently vanitas objects—food, flowers, portraits, skulls117—more importantly, the logic of his work is utterly consonant with vanitas painting. All the objects on Bailly’s table signify the brevity of life, but the work identifies the image itself as the ultimate vanitas symbol: by isolating a particular moment it actually magnifies the passage of time. Warhol makes precisely this same identification, but he does so in the age of mechanically reproduced photographic imagery. Susan Sontag famously argued that in fact “all photographs are memento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.”118 That may be true of the singular photograph (or rather the single iteration of a photograph), but Warhol’s point is that something very strange happens when photographic mementos become the objects of mass production and distribution—a kind of forgetfulness sets in. Bill Manville once hauntingly described Warhol’s oeuvre as

Life magazine taken to its final ultimate absurd and frightening conclusion, pain and death given no more space and attention than pictures of Elsa Maxwell’s latest party. And all of us spectators at our own death, hovering over it all in narcotized detachment, bored as gods with The Bomb, yawning over The Election, coming to a stop at last only to linger over the tender dream photos of Marilyn. (And they call it Life).119

If there is any doubt that death had been Warhol’s dominant theme since the early 1960s, he made it overt in his 1963 Death and Disaster series. In Five Deaths Eleven Times in Orange (1963), for example, he silkscreened a horrific photograph of mangled bodies trapped inside an overturned car. And the cruelty of the photo deepens as Warhol coldly repeats the image eleven times and assigns the work its flatly descriptive title. In direct continuity with his previous work, he treats death as a spectacle, compulsively reiterating images that are, as Donald Kuspit puts it, preoccupied with “premature and public death, instead of what death is supposed to be: a solitary event in which one meets one’s maker and oneself.”120 And as Crow rightly argues, this produces an effect that sharply cuts back on itself, generating “moments where the brutal fact of death and suffering cancels the possibility of passive and complacent consumption.”121 However, for Warhol these images were also apparently marked with religious implications. Zan Schuweiler Daab has shown that the photograph used for Five Deaths appears on the cover of a religious pamphlet titled Your Death, which was found in Warhol’s archives.122 The date and origin of the publication are unknown (printed sometime after 1960), and it shows a slightly tighter cropping of the photo than the one Warhol used (which suggests this isn’t his only source for the photo). The pamphlet consists of several articles discussing the fear that the “Judgment Day” may happen at any time and thus the urgency for each person to be spiritually prepared. The pamphlet puts the questions bluntly: “Spiritually, are you living or dead in sin? Have you the Son of God or not?”