How a Boat Sails • The Parts of a Sailing Rig • Basic Sail Trim • The Points of Sailing Tacking • Jibing • Docking Under Sail • Anchoring & Mooring Under Sail Sail Handling & Storage • New Sailboat Types

Sailing is an old and complex art—sailors can spend a lifetime at it and still find that there is more to learn. It is also a simple and enjoyable activity. A beginning sailor can have a fine time in a sailboat on his or her first day out, provided a few precautions are observed regarding the weather and safety on the water.

Experienced powerboat people, as well as those new to water sports, are taking up sailing in increasing numbers. While most of the seamanship and piloting chapters in this book apply equally to sailboats and powerboats, there are terms used specifically on sailboats and special equipment used to accomplish many sailing seamanship maneuvers.

HOW A BOAT SAILS

The art of sailing, one of the oldest studies in the world, has been joined by the science of sailing, with its complex laws of physics and the lofty mathematics that describe them. Fortunately, along with the wind tunnels, sensing devices, and computers that confront us with all of sailing’s complexity, there has come technology that has broadened the methods and materials we use to build and sail boats. The improvement in construction and safety of sailboats is obvious—and no less so the ability of modern sailors to take advantage of it—but both the art of sailing and the science of sailing are very much works in progress.

While sailors can take heart that the underlying physical phenomena can be used without being completely understood, it should be noted that sailing has been studied assiduously for centuries. The interaction of the wind, water, hull, sails, and keels—to say nothing of the involvement of sailors—is complex, often simultaneous, and, indeed, at times invisible and even intuitive. But each progression in its understanding has led to easier and faster ways to sail.

Keep in mind that while the following discussion of how and why a boat sails is broken into sections so as to be intelligible, the elements that are discussed in isolation are in fact seldom isolated. On a sailboat, little happens that doesn’t have an effect on everything else.

Bending the Flow

Sails extract energy from a flow of air (the wind) by bending it as it goes by. This is true of every kind of sail, ancient or new, and it is true whether the sail is moving across the wind or being blown along with it. As they create a driving force, or lift, from the wind, sails also create a small amount of drag—the smaller the better.

The underwater surfaces of a boat, meanwhile—whether the carefully shaped hull and highly efficient foils of a racing yacht or the broad and bulky underwater expanses of an old-fashioned cargo hull—bend the flow of water that passes over them. The interesting thing about sails (“airfoils”) and keels and rudders (“hydrofoils”) is that, while they operate in very different fluids, the principles that govern them are the same.

Push Equals Shove

A sailboat hull, driven by aerodynamic forces, accelerates until resistance from various forms of drag, both aero-and hydrodynamic, equals the driving forces. At that moment, the sailboat stops accelerating and travels at a constant speed—constant, that is, until something changes. This equalization of driving and dragging forces may be short-lived as the boat sails into a changing wind, is buffeted by waves, or alters the delicate flow patterns through the actions of its crew. The crew, of course, hopes to alter the equalization in favor of the driving forces, causing the boat to accelerate. When the crew is successful, a larger drive is soon countered by a larger drag and, once again, the boat settles into a “steady state”—but at a higher speed.

Airfoils vs. Hydrofoils

Sailboats and airplanes bear some kinship because both depend on a careful use of fluid motion over curved surfaces. But a sailboat operates within two fluid media—air and water—whereas an aircraft operates in only one. The airplane’s airfoils (wings) pull in one direction—upward.

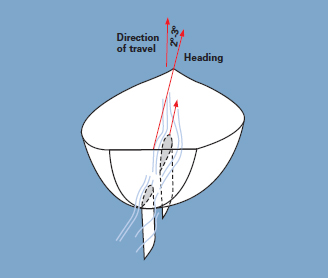

The sailboat’s foils pull in nearly opposite directions—the sails to leeward and the keel to windward; see Figure 8-01, left. Each depends on the other to make the sailboat work—to make it move. Sails could not extract energy in any useful way without the work of the keel, and the keel could not do its work if the boat were not being pushed; see Figure 8-01, right.

Historically, the airfoils on a sailboat (its sails) have received a lot more attention than the hydrofoils. Designers have developed complicated ways to make them more efficient over a range of wind speeds by changing their shapes and their angles to the hull. On the other hand, hydrofoils have been left pretty much on their own while the boat is underway. But this is changing. Designers are now finding ways to modify the shapes of keels, including the addition of trailing edge flaps like those used on aircraft wings.

Figure 8-01 The sails and underwater surfaces of a boat both act as foils. The sails bend the flow of air over their surfaces, converting some of its energy into forward and lateral motion (lift), and some into drag. At the same time, water flowing past the hull and its appendages produces lift to windward, as well as drag.

Bernoulli’s Discovery

In the early 1700s, the Swiss scientist Daniel Bernoulli established that changing the velocity of flow of a fluid, such as air or water, at a specific point brings about a consequent inverse change in pressure at the same point. Bernoulli’s law led to its application in the venturi effect—such as when the flow of a fluid in a tube is constricted, resulting in increased velocity and decreased pressure—and the development of the curved foil. The most convincing demonstration of the venturi effect is easy to perform in the kitchen. First, run a stream of water from the faucet. Then, dangle a soupspoon by the tip of its handle and move its convex surface slowly toward the stream. Rather than being pushed away, as your intuition might suggest, it is pulled into the stream.

Action of Flow Over Foils

The most familiar practical application of the venturi effect is seen in the behavior of an airfoil, such as an airplane wing. As the aircraft moves along a runway, the induced airflow (from the plane’s motion) separates as it strikes the leading edge of the wing. The velocity of the airflow forced to travel over the airfoil’s convex upper surface increases because it spans a greater distance than the air that travels beneath the wing.

Following Bernoulli’s law, the increased velocity on the upper surface of the wing is accompanied by a decrease in pressure relative to that on the wing’s under surface. Since a region of high pressure will try to push into one of low pressure, a force is produced. Aviators began calling this force LIFT, and we use the same term when talking about boats. (The term “lift” also has another meaning, discussed later in this chapter.) Depending on the shape of the surface, the speed of the flow, the angle at which the foil meets the airflow, and other factors, more or less lift is produced. The faster an aircraft’s forward motion induces airflow across its wings, the greater the pressure differential and the greater the lift. Ultimately, the high-pressure area beneath the wing, in attempting to displace the increasingly lower pressure area above it, lifts the wing—and the aircraft to which it is attached—upward and off the ground.

An asymmetrical airplane wing, curved on the upper surface and almost straight on the lower surface, can produce some of its lift even when it is pushed in a line parallel with the oncoming airflow—that is, with no ANGLE OF ATTACK. The sails on a sailboat, acting as a vertical wing or airfoil, ordinarily don’t have thickness the way an airplane wing does. Lacking thickness and asymmetry (because they have to produce lift alternately on both sides), sails must be presented to the flow of air at an angle; see Figure 8-02, upper. This is why sailboats lose their drive, or end up IN IRONS, when they are steered too close to the wind.

When a sail is set at an efficient angle, air flows across its leeward surface at greater velocity than across its windward surface, and a low-pressure area is created to leeward. The sail tries to move into it, impelled by the relatively higher pressure on its windward side. This driving force created by the sails is transmitted to the hull through the mast, sheets, and sail attachments. The boat begins to move, but not necessarily in the right direction—not yet.

Figure 8-02 A thin foil, such as a sail (upper), must be presented to the wind at an angle of at least 30 degrees (called the “angle of attack”) in order to create a lowpressure area across its leeward surface. The sail tries to move into that low-pressure area, producing forward and lateral movement of the boat. Similarly, a keel or rudder (lower) must be presented to the water flow at an angle in order to create high- and low-pressure areas and lift. This angle of attack should only be 2 or 3 degrees..

Drag

As a sail creates lift, it is also creating unwanted DRAG, an unavoidable byproduct of friction and turbulence along the sail’s surface and at its edges. Boats rely on the flow of the wind—relatively slow compared to the much faster airflow generated by an engine-powered aircraft. They are severely limited in the amount of energy they can exploit. When resources are scarce, skills are challenged even more. Being able to change the sail’s shape and the angle at which air flows over it to suit varying wind strengths and directions is critical to extracting the required lift from the available wind energy and to minimizing the inevitable drag.

If there is no corresponding hydrofoil already at work, the result of this careful sail trimming is just unresisted sideways motion, resulting in slower airflow, resulting in less speed—in other words the boat slides aimlessly. You have probably seen this happen when a sailing dinghy leaves the pier with its centerboard up.

Underwater Foils

The addition of underwater fins—a keel or centerboard, and a rudder—vastly increases lateral resistance. Again, unlike most airplane wings, a sailboat’s foils are symmetrical (because they have to work the same way on both sides). Hydrofoils, like sails, must therefore meet the oncoming flow at an angle, called their angle of attack, before they develop any lift. Since most keels are rigidly attached to their hulls, the whole boat has to be aimed a couple of degrees to windward of the course it travels; see Figure 8-02, lower. This isn’t something the helmsman has to think about; rather, it happens naturally, because all sailboats make a bit of LEEWAY (i.e., they sideslip) when sailing on the wind. A modest amount (2 or 3 degrees) of leeway isn’t a flaw that should be corrected; it’s essential for developing the hydrodynamic lift that allows the boat to sail to windward.

As the dinghy sailor lowers the centerboard, he or she might also allow the sail to aim its effort in a more forward direction by letting it out just a little. Now the airfoil and hydrofoil get down to work—against each other. As each begins to encounter faster flow (we are dealing in less than walking speed here, so “fast” is a relative term) each foil begins to produce lift. The centerboard produces lift to windward as well as drag, while the sail produces lift to leeward and slightly forward. It’s the “slightly forward” that makes things happen.

Creating more lift (and causing less drag) is the ultimate objective of high-performance sail and keel design. (This also explains why there are now designers who specialize in “appendages,” keels and rudders, and others who design hulls—both separate from the people who design sails.) Of course, they have contrived a whole set of labels and rules to talk about it. Two important labels in this discussion are CENTER OF EFFORT (CE) and CENTER OF LATERAL RESISTANCE (CLR). These are really just two sides of the same coin, because both centers involve foils—“effort” for the sails, and “lateral resistance” for the keel and rudder; see Figure 8-03.

Now that computers are able to analyze the contribution of every carefully shaped square inch of foil surface, the center of effort and its twin, the center of resistance, are much easier to find. Both centers are simply the sum of all of the lift and drag forces at work anywhere on the foil. If you had to attach a string somewhere on the sail and another on the underwater surface, and pull the boat along by these two strings—creating the same force and balance as a particular strength and direction of wind—the center of effort is the place where you would attach the sail’s string, and the center of lateral resistance is the place you would have to attach the underwater string.

Figure 8-03 The center of effort (CE) is the position of the sum of all the lift and drag forces produced by the sails. The center of lateral resistance (CLR) is the equivalent position of all forces produced by the hull and its appendages. When the two centers are balanced against each other, the boat travels in a straight line (upper). When they are out of balance, the boat turns. Changing the rudder angle (lower) shifts the combined CLR aft so that the boat turns to leeward.

The Balancing Act

Both centers (CE and CLR) are constantly changing with boat motion and sail adjustment. Unfortunately, the net effect of lift and drag that the CE represents does not pull the boat straight ahead. (Remember that we said the boat would start to move, but not in the desired direction.) The force acting at the CE on the sails pulls partly forward but mostly to leeward, and the forces acting on the CLR of the hull, keel, and rudder act to windward and slightly aft. These forces are in balance when the boat is traveling in a straight line. When they are out of balance, the boat turns; refer to Figure 8-03.

Keeping in mind that a boat sails fastest when its keel and rudder are presented to the water flow at a slight angle, designers place the sails on the hull in such a way that, if no steering force were applied with the rudder, the boat would turn itself gently toward the direction of the wind (WEATHER HELM). When the boat is sailed, a straight course is achieved by the gentle application of 2° or 3° of rudder angle in the opposite direction; see Figure 8-04. In a well-trimmed boat, the keel will have an angle of attack of 2 or 3 degrees by virtue of leeway, and the rudder’s angle of attack might be 4 to 6 degrees by virtue of leeway plus the slight rudder angle required to counteract weather helm. However, you can have too much of a good thing. An excessive imbalance between CE and CLR, one that requires more than a slight rudder correction, causes the rudder to develop drag commensurate with the greater lift it is being forced to create. The boat decelerates—slower speed means less drive from the sails—and things settle back into the drive-drag equilibrium at a slower speed.

Figure 8-04 The keel (or centerboard) must be presented to the water at a slight angle of attack (ideally 2° to 3°) in order to create maximum lift, and the rudder will need 2 or 3 degrees of deflection to counteract weather helm. Thus, the rudder’s overall attack angle will be 4 to 6 degrees.

In moderate wind (up to 10–14 knots), a sailboat that is properly balanced exhibits a weather helm—a tendency to turn into the wind. This is counteracted by pulling the tiller slightly to weather (the direction of the wind) or turning the wheel away from the wind. A sailboat that acts in this way is considered safer because in the event of gear failure or lack of attention to the helm, it will round up (head into the wind) rather than fall off into a possibly dangerous jibe (pronounced with a long “i” as in “ice”). Weather helm should decrease as wind strength abates.

A LEE HELM is the opposite of weather helm, a tendency for the boat to wander off to leeward; many sailboats develop a slight tendency for lee helm in light air. Acceptable in very light winds, lee helm is undesirable in stronger winds. A straight-line course can only be achieved when the rudder is turned to create a force pulling to leeward (so the bow is pushed to windward). This means that no windward lift is being created by the rudder, so all of it has to be created by the keel. The keel then ends up at a more extreme angle of attack to produce this lift, and in the process creates more drag. The boat makes more leeway and slows down.

It should be noted that all of these differences in balance are important to the cruising sailor as well as the racer. Though they are difficult to perceive—3° is hard to see and often difficult to feel in the helm—they produce substantial differences on almost all points of sail. The racing sailor may lose a race, but the cruising sailor may make serious errors in navigation by failing to account for large leeway angles that result from excessive imbalances.

Incidentally, keels and rudders can be a lot smaller in area than sails because they operate in a denser medium. In addition, when they are pushed through the water at greater speeds, they can produce sufficient side forces with less area—that’s why the crews of fast, planing catamarans often reduce drag by pulling up their foils (usually daggerboards) a few inches at high speeds, even though they are sailing upwind.

Conversely, if there is no speed at all, there is no flow and neither the keel nor the rudder can do its job. A boat that has no way on cannot be steered, which is why STEERAGEWAY is so important. Skippers will often do whatever they can to get a boat settled down and underway so as to create some flow past the keel and rudder before they worry about what precise direction they’re going.

Outsailing the Wind

For most novice sailors, the idea that a boat can sail faster than the wind is questionable at best. Even the less ambitious claim—that a boat can receive more power from the wind as the boat picks up speed—seems contrary to common sense. After all, there is no source of power other than the wind.

The Effect of Apparent Wind

But it’s true, and an understanding of APPARENT WIND, the stronger wind partly created by the boat’s own speed, is crucial to sailing. Let’s look at two extreme examples—a very slow boat and a very fast boat.

The slow boat is a Spanish galleon. It has no separate keel and, by modern standards, inefficient sails. It sails most effectively with the wind behind it, and even then it doesn’t sail very fast. If the galleon were just getting underway, and if the wind were exactly on its stern and blowing at 10 knots, the wind felt by someone standing on deck would be 10 knots. As the galleon picked up speed, the wind felt on deck (the apparent wind) would decrease, because the ship would be moving along with it. The effect of the wind on the moving sails would also decrease. At somewhere around 2 knots of vessel speed through the water, the decreasing force created by the sails would exactly balance the increasing resistance of the hull (discussed later), and the galleon would stop accelerating and settle down for a long trip to its destination. Vessel speed would be 2 knots, wind speed 10 knots, apparent wind speed 8 knots.

Now take the fast boat—an iceboat—in a similar situation. With almost no hull resistance to overcome, the iceboat picks up the same 10 knots of wind from directly astern and, within seconds, the skipper is aware of a rapidly decreasing apparent wind. His boat reaches a balance between the decreasing force of the wind and the increasing resistance of the iceboat at, for example, 9 knots (boat speed 9 knots, wind speed 10 knots, apparent wind speed 1 knot).

Now, 9 knots would be pretty exciting in a Spanish galleon, but in an iceboat, it’s not worth chilly feet. So the iceboat skipper turns his boat so that it begins to travel on a line perpendicular to the wind. He does this without losing any speed, so his initial speed, after the turn, is still 9 knots. At that instant, the iceboat skipper feels the full force of the 10-knot wind, because he’s no longer traveling away from it. He also feels the force of a 9-knot wind, just as if he were on a bicycle pedaling at 9 knots. These two vectors, at right angles to each other, can be added (vector addition is discussed in Chapter 17), the result being an apparent wind of about 13.5 knots flowing into the iceboat at an angle of about 47° off the bow.

The Spanish galleon, still traveling at 2 knots, also turns so that it is sailing on a line perpendicular to the wind. The new wind across its decks is also a vector sum of the 10-knot wind and the 2-knot boat speed. The result is a less-than-impressive 10.3 knots at an angle of about 79° off the bow. The galleon responds to this slightly stronger apparent wind (which is still hitting at an angle wide enough for its square sails to make use of) by accelerating. Again, the force on the sails is balanced by the increasing resistance of the hull, and things settle down again—at 2.5 knots.

However, aboard the iceboat, things start to happen. Its highly efficient sail and almost-zero hull resistance respond to the new, stronger wind. It begins to accelerate again. The first one-knot increase in boat speed, to 10 knots, brings a new apparent wind, 14.1 knots, at a new angle of 45 degrees. This angle is still no problem for an iceboat sail, so it responds to the new apparent wind strength by gaining another knot. Now the apparent wind is very close to 15 knots and the angle is still comfortable—producing more acceleration.

Where does it all end? Well, this is not perpetual motion (though, in an iceboat, it can often feel that way!). Things start to level off when the apparent wind goes so far forward that the sail begins to point too directly into the wind. It can no longer achieve a useful angle of attack, and it luffs. At this point the iceboat is probably experiencing an apparent wind of almost 45 knots and is doing almost 40 knots of boat speed—pretty good for a wind strength of 10 knots. In fact, with strong winter winds and cold, dense air, iceboats routinely travel at speeds of more than 50 knots. At that speed, their sails are strapped in tight regardless of what direction the “real” wind is blowing—their apparent wind is far more important, and it’s blowing from almost straight ahead; see Figure 8-05.

The effects of apparent wind on most sailboats are far more dramatic than aboard the galleon and far less than aboard the iceboat. Even a heavy racing sloop might increase its speed by 25 percent as a result of a stronger apparent wind. Sailboats that are less limited by their weight can easily double their speed with careful use of apparent wind.

There are some fundamental rules about apparent wind:

• Except when sailing directly downwind, apparent wind will always come from “farther ahead” than the true wind does.

• Sailing on any angle ranging from perpendicular to the wind to an angle quite close to the wind, apparent wind will always be greater than the true wind.

• As wind strength increases, the angle of the apparent wind moves farther aft; conversely, as wind strength decreases, the apparent wind moves farther forward. A strong gust of wind is usually welcome because it provides more power applied from farther aft.

Figure 8-05 Apparent wind is the direction of the wind as it appears to a person on board. Both boat speed and the boat’s angle to the true wind affect the direction and strength of the apparent wind. In the vector diagram shown here, the yellow arrow is the wind from the boat’s motion, and the white arrow is apparent wind. Apparent wind is greatest when the boat is sailing perpendicular to, or at an angle close to, the actual wind.

Heeling

For the most part, boats sail most efficiently in an upright position so that aerodynamic and hydrodynamic lifts are converted into forward motion. But the same dynamic forces that pull the boat forward also try to push it over.

The sails, which have their CE at about 40 percent of the height of the mast, and the keel with its corresponding CLR well below the water, both act as levers with the hull in the middle as their fulcrum.

In general, there are two ways to counter these forces and prevent them from pushing the boat over and capsizing it. These are weight and width; see Figure 8-06. Both have disadvantages. Energy extracted from the wind is partly absorbed in the work of moving weight, especially if that weight begins to move up and down through waves, so any extra weight robs speed. Width makes a hull harder to push through the water (unless the boat is separated into two hulls, or three, that are spread apart).

Most sailboats use both weight and width to stay upright. The width of the hull is the first line of defense because buoyancy begins to provide substantial righting moment (it pushes back) as soon as the hull begins to heel. Fixed ballast gains in importance as the hull heels farther over.

Different sailboat designs rely more heavily on one or the other method. The classic heavy, narrow “meter boats,” such as the 12-meter class formerly used in America’s Cup competition, were intended to balance at a substantial angle of heel sailing close to the direction of the wind. Designers shaped their hulls in such a way that they would have greater potential speed when heeled than when upright.

Figure 8-06 In these illustrations, B is the center of buoyancy and G is the center of gravity. Sailboats can use either weight (left) or width (right) to remain upright against the force of the wind. A hull stabilized primarily with weight has a very small righting moment as it begins to heel, but that increases steadily as the craft heels farther over. Such boats are initially “tender” and ultimately “stiff.” As the wind increases, a ballasted hull will lean over, increasing the righting moment, but the wide, unballasted hull has already achieved its maximum righting moment and is becoming increasingly unstable as the angle of heel increases.

Most recent racing designs, such as the J-24, rely more on a wide, shallow hull. With this hull type, crew weight becomes even more important, especially because crew weight can begin to provide righting moment even before the hull begins to heel. That’s why the best-sailed dinghies sail through gusts of wind without heeling—their crews move into position in perfect synchronization with the changing aerodynamic forces, converting every increase in power into forward acceleration rather than heeling.

As the boat begins to heel, several factors combine to rob it of forward speed. The force created by the sails is now aimed partly downward (instead of parallel to the water), thereby helping to immerse the hull into the water rather than pulling it forward. Less sail area is exposed to the horizontal movement of the wind. A corresponding deterioration takes place underwater, where the flow of water across the keel and rudder are compromised. The part of the hull that is underwater becomes asymmetrical, creating turning forces that have to be counteracted.

A more subtle change also takes place. The forces created by sails and keel are no longer acting directly above and directly below the hull—they’re both displaced sideways. The effect is similar to what would happen if you were pulling the hull with a towline. When the boat is upright, the towline pulls along the hull’s centerline. As the boat heels, the effect is as if the towline were uncleated and made fast again at the gunwale near the widest point of the beam. In this case, you would expect to fight the boat with its rudder to keep it on a straight course. When the boat heels, its propulsion forces operate away from the hull’s centerline. That’s why boats that are allowed to heel too far under the pull of a spinnaker are so vulnerable to broaching. It also explains why, when a sailboarder leans back into the wind at high speed, he must also move to the tail of his board, holding the sail well aft of the point on which the board pivots when it changes direction.

Achieving Stability

It’s no wonder the Polynesian solution—dividing the hull into two (or three) units and placing them far apart—is attractive. With no penalty in weight, a catamaran or trimaran achieves huge righting moment at the slightest angle of heel.

However, that’s not the whole story. When stability is achieved entirely by righting moment from hull width (or by spreading the hulls farther apart), righting moment is typically very high at small angles of heel—but decreases steadily to nothing as the boat heels farther over. In one sense, when you need it most, it’s all gone; see Figure 8-06,.

Conversely, the righting moment provided by fixed ballast is small as the hull begins to heel, but steadily increases as the hull heels farther; in other words, the boat is initially TENDER and ultimately STIFF. When the heel angle nears 90 degrees, the mast is almost parallel with the surface of the water and the fixed ballast is almost sideways. At this radical heel angle, righting moment is at a maximum and heeling force at a minimum.

Keep in mind that these examples are highly simplified. Many other factors, such as the wave conditions present when such extreme heeling forces are at work, have to be considered by yacht designers. For example, even though the fixed-ballasted boat may not heel beyond this extreme angle, it may be filling itself with water. Even though the powerfully rigged, unballasted multihull may potentially capsize, it is less likely actually to founder (since, being unballasted, it is generally lighter than water).

Boat Speed

Few activities inspire participants to seek the smallest improvement in speed as sailing does. Indeed, it is the potential for almost infinitesimal improvement that is one of the joys—and at times the frustration—of sailing.

Most sailors are not particularly concerned with going faster than any other sailboat—they’re more concerned with getting the most speed out of a sailboat that has been designed with speed-limiting rules. They want to maximize the potential of a boat that has been designed to sail within a class of boats that are all very much the same, if not actually identical in performance characteristics.

This historical limitation of sailboat design has led to a paradox: While sailors have developed the art of boat preparation, sail trim, and steering to a high degree of refinement, and yacht designers have squeezed every last fraction of a knot from conventional hulls, keels, and sails, the vast majority of sailboats have remained within a narrowly defined set of basic configurations. The imaginative application of pure science and engineering has not had much impact on the activities and experience of most sailors. Nevertheless, the principles that determine how fast a sailboat can go are eagerly studied and applied with an increasing degree of subtlety.

One of the chief enemies of speed for a sailboat, as for any vehicle traveling through a fluid—whether water or the atmosphere—is drag. But sailboats encounter two kinds of drag whose relative importance varies with speed. The first and most obvious is the drag caused by the friction of air and water flowing over large surfaces that can never be perfectly smooth. For that reason, yacht designers take great pains to reduce the wetted surface of the hull. For any given volume, the shape with the least wetted surface is a sphere (that’s why soap bubbles are spherical), but a sphere is not very useful for a hull. The next best compromise might be a round tube. Many hulls are developed from that principle and have almost a circular cross section.

Drag is also caused by turbulent flow around the awkward shapes of deck fittings, rigging attachments, through-hull fittings, and even the crew themselves. While attempts are made to streamline these, there are practical and rule-oriented limitations that most sailors happily accept.

Drag from friction and turbulence is most important at low speeds—not because it diminishes at higher speed (it doesn’t) but because on a conventional sailboat another form of drag becomes even more difficult to control. This is FORM DRAG, the process of energy loss through the formation of waves.

Hull Speed

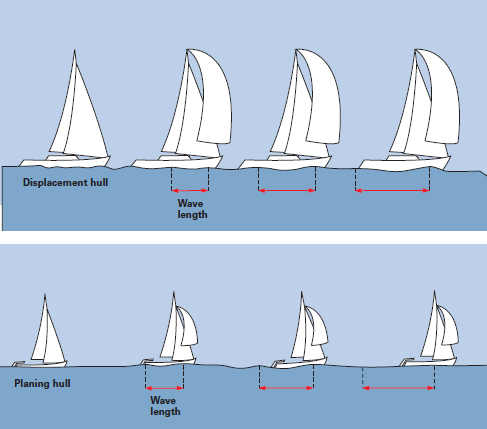

Imagine a sailboat moving through the water at less than a knot. Tiny wavelets stream from the hull at several points along its waterline. They don’t seem to be connected. As speed increases, the wavelets grow into waves and seem to join, the trough of one running up into the crest of the next; see Figure 8-07, upper. At this point, you could measure the boat’s speed by measuring the distance between one wave crest and the next: The speed of a surface wave is strictly related to its length. To measure the relationship, in knots, of waves in water, yacht designers use the square root of the wave length, in feet, multiplied by 1.34.

Figure 8-07 When a hull moves through the water, It produces waves that result in energy loss. The maximum speed of a conventional displacement hull (upper) is a function of the longest wave that it can make, which in turn is determined by hull length. No amount of sail can create enough power for it to go faster. On the other hand, the planing hull (lower), such as a racing dinghy and some multihulls, can carry enough sail to push it over its own bow wave and onto a plane.

Three crests along the side of the boat indicate that it is traveling at about half of its maximum speed. As speed increases, the bow wave grows in height and length, pushing the midships wave aft. As the last fraction of a knot is reached, the stern wave is almost falling behind the hull—but it can’t. As the stern wave pulls aft, the stern settles down into it. Drag increases because the hull is actually inclined upward against the slope of the bow wave. The hull is trapped.

The implication is that you should always have enough propulsion power to climb over the bow wave and convert from a floating or displacement mode of support to a planing mode. That option is available to very light boats that can carry lots of sail (racing dinghies, multihulls, sailboards, and even foil-supported boats), but it’s not available within the realm of ballasted monohulls.

Therefore the implication for conventional boats is that as long as a hull is trapped in its own wave, the vessel will never go faster than the longest wave it can make. That is the reason why longer boats are faster—and why, almost from the beginning of sailboat racing, length has been heavily factored into rating rules.

The challenge, within the limitations of rules and economics, is to make a longer wave, so that the hull has a higher potential speed when the propulsion power (wind) is available, but to do so without seriously compromising the hull’s performance when windpower is scarce.

Designing for Speed

One common strategy is to design a hull that has two “personalities”—a shape that is relatively narrow and fine at the ends of the waterline when upright (at low speed when form resistance is less important), and a heeled, or high-speed, shape that is full at the ends. An overhang at the stern is very useful in this regard; as the stern wave builds, the waterline becomes longer and fuller, delaying the point at which the stern begins to settle down into the wave.

Obviously, this dual personality has limitations. In fact, if the designer has made the bow and stern of the boat especially fine so that they will be easier to push through the water, the waterline will actually seem short to the wave, and the top speed will be lower. This leads to the paradox that hulls meant to travel at or near hull speed most of the time tend to be rather full in the bow and the stern, while hulls expected to travel more slowly, while making more efficient use of lighter winds, might be finer fore and aft.

If heavy winds were always available on demand, and if sailboats always traveled with large apparent winds, yacht design would, of course, be much simpler. However, maximum driving power from a sailboat rig is rarely available, and conventional hulls therefore have to be designed in order to strike the best compromises.

Some very light sailboats, such as racing dinghies, are able to provide lots of propulsion power by having their crews hike out against the power of large sails; see Figure 8-08. Since they are short, these boats reach their wave-resistance limit at a very low speed (just over 5 knots). But they have lots of propulsion power still to absorb. Without much fuss, they rise over their bow waves and plane, just like powerboats, often reaching a significant 17 to 20 knots. Of course, it takes two heavy sailors and perhaps three straining sails to do it, but that’s all part of the attraction.

Figure 8-08 This multihull racing dinghy is moving at high speed on a plane, literally leaping out of the water. Its crew must “hike out” on a trapeze to keep the boat reasonably level.

Multihulls

Catamarans and trimarans, with their unique stability, also have physics on their side when it comes to making waves. Because their hulls can be so much narrower than a monohull, the waves they produce are consequently much smaller. While the relationship between wave length and speed still holds, the “hole in the water” that is created by the passage of a narrow hull is much smaller. The stern of a narrow hull doesn’t have so far to settle, and drag does not increase as much or as suddenly. In one sense, the narrow hull of a catamaran or a trimaran doesn’t have to plane because it has broken the hull-speed rule.

THE PARTS OF A SAILING RIG

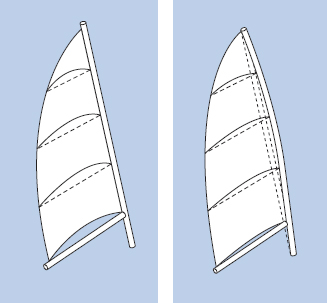

Figure 8-09 A mainsail might seem to be a simple cloth triangle, but its construction is based on a complex mix of curves that the sailmaker uses to create the proper camber (i.e., belly, or shape). Commonly made of Dacron, the sail is reinforced at its edges and corners with patches of extra material, and given stiffness in the roach by battens.

Technology has contributed many innovations to the art of sailmaking, mainly in the area of sail material. The woven polyester fiber, usually referred to by the trade name Dacron, that replaced canvas and cotton remains the most common of the new fibers. Nonetheless, in the constant quest for greater strength and less weight and stretch, Dacron has been joined by fabrics made of Mylar, Kevlar, Spectra, carbon fiber, Zylon, Vectran, and nylon for light sails.

With few exceptions (such as the spinnaker, discussed separately later), a conventional triangular shape has emerged as the most popular sail configuration. The luff of a mainsail is attached to the mast, while the foresail’s luff is attached to a forestay. While some mainsails are “loose footed” and attached only at the fore and aft corners (the tack and clew), more often they are attached along the length of the boom either by a boltrope sewn into the sail or by slides. Most foresails are loose footed. See Figure 8-09 for the parts of a sail; see Figure 8-10 for a representative range of sails.

Figure 8-10 A boat may carry sails of different sizes and weights to suit different conditions of wind velocity or points of sail. Shown here are the basic sails that a ketch might have on board. The largest jib, the one whose area extends beyond the triangle formed by the forestay, mast and deck (the foretriangle), is called a genoa. Though it is the largest headsail, the genoa is made of the lightest material to catch the slightest breezes. The storm jib, the smallest sail, is made of the heaviest material to withstand strong winds. The modern trend is to replace several headsails with one roller-furling sail that can be sized to match the wind velocity.

Sails are not flat like paper. They are carefully cut and assembled so as to present a subtle shape, curving both along their horizontal and their vertical lines. The quality of these curves and their ability to be slightly altered underway are what makes sailmaking such a competitive science. Not only must sailmakers design the right curves for each boat and for a variety of wind and wave conditions, they must also design a structure that will maintain its shape despite heavy stress and the effects of violent shaking and sunlight.

The largest stress on most sails, especially mainsails, is along the LEECH from the CLEW to the HEAD. This unsupported edge has to accept the pull of the mainsheet and must also take the pressure of the wind flowing off its windward side. On almost all recent designs, the leech also carries a deep outward curve, a ROACH. To counter these loads, most sailmakers lay out the sail material so that the low-stretch fibers of the weave run parallel to the leech. That design dictates panels of material that slope down from leech to LUFF.

But many other patterns are in use as well. Some place different materials at high-stress areas of the sail, even going so far as to stitch and weld strong fibers in elaborate elliptical curves that radiate out from the foot and luff. At the other extreme are cruising sails that can easily be rolled onto furlers and have straight, soft leeches.

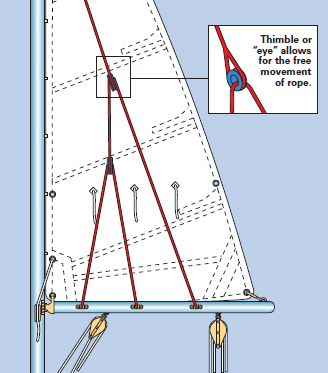

BATTENS provide additional support at the leech of a mainsail. Traditionally, they are flexible slats of wood or plastic that slide into long pockets. But that tradition is changing too. Catamaran sailors discovered that by extending battens from the leech all the way to the luff they could have a sail that would maintain a curve at very narrow angles to the oncoming airflow. Such sails have become popular even among cruising sailors who feel that, although they add extra weight, they are easier to manage and will last longer. Full-batten mains have led to a number of additional items of sail hardware to allow the forward end of the batten to be flexibly attached to the aft face of the mast, and so slide up and down freely despite the pressure.

Most sailors attach ribbons or pieces of wool to both sides of the sail; these TELLTALES, or TICKLERS, indicate the efficiency of airflow over the sail. Often sailmakers sew windows of plastic near the telltales to make the action of a leeward one more visible. Large windows are sometimes sewn into dinghy mainsails and “deck-sweeping” foresails for better leeward visibility when racing or sailing in confined conditions.

Spinnakers, in all their variations, are usually made of nylon. Since spinnakers generate their drive from the push of the wind, they can be allowed to stretch, thereby taking full advantage of the ultimate strength and lightness nylon provides. However, the architecture of spinnakers is just as complicated as it is for other sails. The goal is to produce a very full CAMBER, but one that still stands up to the flow of air from one edge to the other—spinnakers do not simply fill with air like a balloon. Lightness is a requirement to allow the sail to set high and away from the interference of the mainsail, and to present the largest possible area to the wind. The fact that spinnakers are usually colorful is a matter of tradition more than function, but it does mean they are easier to examine against a bright sky for fine-tuning the trim.

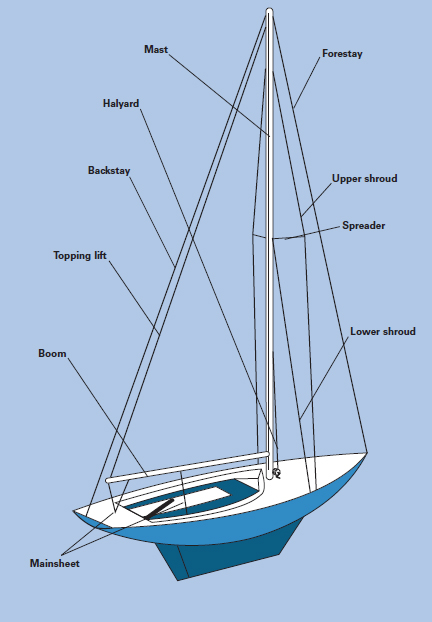

Standing Rigging

Standing rigging is the structure designed to support the sails and to help transmit the power they develop to the hull. In most discussions, the mast itself is considered to be the main component of the standing rigging. The idea that the standing rigging is set up permanently and should not move (hence “standing”) has given way to high-performance engineering and tinkering. It is now fairly common to find standing rigging that is substantially altered while underway, and masts that are not only allowed, but forced, to bend. The distinction between standing and running rigging has begun to blur. Figure 8-11 illustrates the major components of standing rigging.

Figure 8-11 Standing rigging supports the sails and transmits to the hull the power that they develop. The most common arrangement is a mast supported by stays and shrouds. Running rigging includes halyards for hoisting the sails and sheets for trimming them.

Masts

The evolution of mast making has focused on attempts to increase strength while reducing weight aloft. The challenge to make the structure lighter and stronger is complicated by the fact that for any given sail area, more power can be extracted with a tall, narrow shape than with a short, wide one. The ASPECT RATIO of sails (the relation between height and width) is limited by the fact that they become harder to trim as they get taller; but for purposes of performance under sail, masts can never be too tall or too thin—and are often extremely expensive.

Traditional wooden masts and booms have given way to extruded aluminum tubes and, more recently, to tubes made of composites of such materials as carbon fiber and epoxy. The simplest mast for a small, single-sail dinghy (such as the Laser) is a round aluminum tube held in a simple socket in the deck. The sail is attached to the mast by means of a sleeve extending the full height of the luff.

Although free-standing masts are sometimes used on larger sailboats (some even have more than one free-standing mast and sail-sleeve attachment), a much more common arrangement uses traditional stays and shrouds as guy wires from the mast to the deck. The mast may pass through the deck to rest on a step at the keel (KEEL-STEPPED) or fit into a step or TABERNACLE on deck (DECK-STEPPED).

Stays & Shrouds

There are almost infinite configurations for stays and shrouds, but at the forward side, there is always a forestay (also known as a headstay) running from the bow (or near it) to the top of the mast (or near it). When the forestay is attached to a point below the top of the mast (called a FRACTIONAL RIG), the top of the mast can be pulled backward to create a slight bow shape. (The reasons for doing this are described in the section on sail trim.) There might also be a second forestay aft of the first, either for more precise control of mast bend or for carrying a smaller inner headsail, or STAYSAIL.

On high-performance rigs there might also be a JUMPER STAY running from the mast, over a strut (JUMPER STRUT or DIAMOND STRUT), and back to the mast at the top. Tension on this stay holds the mast tip against the pull of the mainsail leech, especially in a fractional rig.

A backstay, running from the mast tip (TRUCK) to the stern, may be a single wire for its full length, or it may split into a bridle partway down and attach to the aft deck at both quarters. Splitting the backstay makes it easy to adjust its tension, because the bridle can be pulled together with a simple block and tackle; see Figure 8-12. The configuration also allows easier access to the cockpit over the transom.

Figure 8-12 Many small cruising sailboats adjust their backstay by pulling a choker (see arrow) downward over a Y-shaped bridle. Larger vessels usually use a hydraulic tensioning system.

Additional backstays are sometimes used on high-performance rigs, and are considered part of the running rigging because they can be loosened completely when underway. In fact, one has to be loosened and the other tightened on each tack or jibe; the windward running backstay is tensioned to add to mast stability, while the leeward one is slackened to allow the mainsail to be eased out. Needless to say, the cockpit of such a craft is a noisy, crowed place on each coming about.

Smaller boats may run shrouds directly from TANGS (attachment fittings) on the mast to CHAINPLATES on the hull at or near the deck. Taller masts cannot use this simple arrangement because, to get the required angle between the shrouds and the mast, the attachment at the deck would have to be outboard of the hull. Instead, struts called SPREADERS provide needed support by giving a wider angle between the upper shrouds and the mast. They push the shrouds outward to maintain supporting pressure on the upper mast; see Figure 8-11.

Single spreaders extend athwartships from the mast a little more than halfway to the top. They are either horizontal or have a shallow upward angle. Some are swept back slightly. Smaller rigs get extra control over mast bend by swinging their spreader tips in a fore-and-aft arc. Larger boats often have multiple spreaders with several shrouds, each to a different level of the mast. No matter what their arrangement, shrouds and stays are meant to keep the mast standing against the forces of wind and sails, or when the mast is deliberately bent, to change the shape of the mainsail.

Stays and shrouds on most sailboats are made of 1x19 stainless-steel wire of appropriate diameter for the size of the rig being supported. Stainlesssteel rod, though more expensive, has been growing in popularity because it has less stretch and more resistance to corrosion than wire. Rod diameter required to provide the same tensile strength is smaller than that of stranded wire and so has less windage (surface exposed to the wind).

Integral to the strength of any piece of standing rigging is its attachment point at the deck. Usually, shrouds and stays terminate in turnbuckles that are attached to the eyes of chainplates, which in turn are bolted directly to the hull.

Tuning the standing rigging involves careful tightening of the shroud turnbuckles until the shrouds on both sides of the mast have the same tension, and the mast remains in column vertically with no sideways bends when the boat is sailing. Once the shrouds are tuned, backstay tension is adjusted by means of tackle or hydraulic pumps to increase or relieve forestay tension and to match mast bend or mast rake to sailing conditions—.

Running Rigging

Running rigging includes all the gear used to raise and trim sails—and sometimes there is a bewildering amount of it. Many crews resort to colorcoded lines to distinguish one piece of running rigging from another. Perhaps the easiest way to understand running rigging is to go through the sequence that most crews would follow to get underway. We will assume that the boat is a 25-foot (7.6m) cruising and racing sloop with a centerboard—a fairly common type.

If it’s not already attached to the boom, the first step is to pull the boltrope on the foot of the mainsail into the groove of the boom. The clew is pulled out to the end of the boom by hand and attached to a short wire called an OUTHAUL, which will later be adjusted. (If there are slides attached to the sail, these are slid onto and along a track on the upper side of the boom.) The tack is attached to the GOOSENECK (the articulated fitting that couples boom to mast) by a short pin. Above the tack is another hole (a CRINGLE) where another short adjusting line—the CUNNINGHAM—may be attached. Some items of running rigging are illustrated in Figures 8-09 and 8-11.

Now, presuming the boat is ready to be cast off, or is already underway with engine running, the mainsail can be pulled to the top of the mast. This requires that the main halyard be shackled to the headboard of the main and that the luff boltrope be slid into the groove of the mast (there might be sail slides on a track instead). The halyard runs loosely up to the truck of the mast, over a sheave (a wheel) and back down the mast to the deck. It may simply be cleated to the mast, or it may run through a block (pulley) to a cleat or LINESTOPPER near the cockpit. Part of the halyard’s up-and-down journey may be inside the mast. Before the main is raised, a check is made to ensure that none of the lines attached to it will restrict the main on its way up the mast.

When the helmsman has headed the boat into the wind and gives the word, the halyard is hauled, the head of the main rises to the top of the mast, and the end of the halyard is cleated in place. Later, small adjustments may be made. With the main exposed to the wind, the sail flaps until the mainsheet is trimmed in. The mainsheet attaches near the end of the boom and controls the in-and-out position of the boom the way your arm controls the swing of a door. Now is also the time to make initial adjustments of the outhaul (and cunningham, if used); by tensioning the cloth along the edges, the position of the deepest part of the sail’s curve is controlled. After the tail of the main halyard is coiled and stowed, it might be necessary to ease the TOPPING LIFT—a line or wire that supports the boom in a level position when the boat is at rest. Now the BOOM VANG should be checked. This line, or telescoping pole, runs from the butt of the mast to the underside of the boom and resists the mainsail’s tendency to lift up the aft end of the boom. Of course, the mainsheet has a role to play here, too.

Selecting & Raising the Jib

Now it’s time to raise the headsail. First, the skipper chooses which one to raise. Bigger jibs are used in lighter winds. (Increasingly, especially on cruising sailboats, one or two roller-furling, roller-reefing headsails replace multiple headsails of various sizes.)

The tack of the headsail is attached by a short pin or a shackle to a point close to the bottom of the forestay. Some boats are equipped with a foil on the forestay, which contains a groove to hold the boltrope sewn into the jib’s luff. Otherwise, the foresail is attached to the stay with a series of HANKS—spring-piston hooks. The headsail itself is loosely bundled on the foredeck; it may be necessary to tie it to the lifelines temporarily. The halyard is attached to the head and made ready to haul, then sheets must be attached to the clew. Unlike the mainsheet, these are normally stowed when not in use. The headsail sheets are best tied through the clew cringle and led back, one on each side of the boat, through their sheet blocks, or fairleads, and draped over the coaming of the cockpit. It’s important not to have them catch while the sail is being raised. (Sometimes, one long line is used for both sheets, attached to the clew at its midway point.)

When the word is given, the crew hauls the halyard and the headsail rises up the forestay. It luffs noisily for a few seconds while the halyard is cleated or stopped, then one of the sheets (depending on which tack the boat takes) is hauled in. Now, minor adjustments can be made to halyard tension and position of the jibsheet leads (which are often moveable fore and aft on a track).

Now the boat is fully under sail. The engine is turned off. The centerboard, very likely, is lowered completely, perhaps using a light winch with a crank for a boat this size. Smaller boats employ a block and tackle called a centerboard tackle, and very small boats have a simple pendant. Obviously, sailboats with a keel have no centerboard adjustment to make.

Adjusting the Sails

From this point, most sail adjustments take place from the cockpit, using the mainsail and headsail sheets. The position of the TRAVELER—a car that moves on a track set athwartships on the boat to adjust the angle of pull on the mainsheet—also has to be set. Depending on many variables (refer to “Basic Sail Trim,”), the traveler car is pulled up to windward, let down to leeward, or positioned somewhere between; see Figure 8-13. Once it is fixed in place, frequent small adjustments are made to the mainsheet to account for changes in apparent wind speed and angle. These adjustments both position the boom laterally and release or apply tension to the leech. Racing crews use the traveler tackle to move the boom in or out without altering leech tension while sailing close to the wind.

Figure 8-13 Shown here on a small sailboat, a traveler is a car that slides on an athwartship track to aid in the proper adjustment of the mainsheet.

Likewise, the headsails are frequently adjusted—some crews would say too frequently. Jibsheet adjustments are made with a winch; see Figure 8-14. On boats larger than about 20 feet (6.1 m), even if the extra mechanical advantage of a winch crank is not necessary, the winch helps by snubbing the sheet until another handgrip is taken. When the wind increases, the headsail can hardly be moved without the mechanical advantage provided by the winch’s gear ratio. (Set aside winch handles carefully; they’re expensive and they sink.) Now, many headsail winches are fitted with a self-tailer, a circular jaw that holds enough tension on the sheet to prevent it from slipping against the surface of the winch drum. As the sheet is cranked in, the tail is peeled out of the jaw automatically. This means sail trim can be accomplished by one person instead of two. For cruising, this is progress; for racing, it means less work for the crew.

The sails on a 25-foot (7.6 m) boat are fairly easy to raise without the help of winches, but a larger boat might have a halyard winch, either mounted at the foot of the mast, or, more commonly, on the aft end of the roof of the cabin. Since winches are expensive, they are often shared among halyards and other adjusting lines. To hold one line in place while another is being winched, boats may have LINESTOPPERS—simple levered clutches that clamp onto the line without damaging it. These are arranged, one per line, in front of the shared winch.

In place of linestoppers, lines may be held by CAMCLEATS with spring-loaded jaws that permit line to run in but not out. Mainsheets, with their load-reducing block and tackle to provide mechanical advantage, are almost always held by large camcleats, but camcleats are otherwise more common on small boats or for smaller, lightly loaded adjusting lines on large boats. Line is released by lifting up and out of the jaws.

Ordinary horned cleats are also useful for sheets, although they are less and less common for running rigging. Used properly, cleats can provide perfect holding power and quick release. (Refer to Chapter 23 for more information on cleating.)

So far we have explored all the line and hardware needed to get the sails up, adjust their shape, change their angle in relation to the apparent wind, and pull the centerboard up and down. We’ve pulled on the backstay, moved the traveler car, and positioned the headsail leads. The next step—flying the spinnaker—perplexes and intimidates novices.

Figure 8-14 On all but the smallest sailboats, winches are used to provide mechanical advantage for trimming the headsail sheets. Most modern winches are now equipped with self-tailing devices so that a single crewmember can handle the winch.

Flying the Spinnaker

For this discussion, we will assume a conventional spinnaker because the other styles are simplifications of it. The spinnaker is attached at three points—the head and the clews. (Note that spinnakers have two clews, although some sailors may logically refer to the windward clew as the tack.) The head is attached to the mast by a halyard, just like other headsails. The clews are attached to the deck with sheets, just like all headsails—except that there are always two separate sheets. The uniqueness of a conventional spinnaker is that it is symmetrical, so that one sheet and one luff are on the windward side of the spinnaker on one tack, but on the leeward side on the other tack. As they change sides, they may change names.

The leeward side of the spinnaker is the simplest. A sheet is attached to the clew; it runs aft to a block on the deck and is trimmed with a winch. When the spinnaker luffs, you pull the sheet in. The windward side is more complicated. Here, the clew also attaches to a sheet that runs aft to the deck at the stern. In this position, on the windward side, the sheet is now called the guy—though it’s still the same piece of line. However, it is held away from the mast by a spar—a SPINNAKER POLE—jutting out at right angles and attached to the mast with an articulated coupling. The outboard end of the pole has a piston hook (or a similar device) that the guy runs through. The spinnaker itself is not actually attached to the pole.

That sounds simple, except that the pole has to be held both up and down. This is done with a pole uphaul and downhaul running from the pole (or a bridle on the pole) to the mast. Both up- and downhaul need their own blocks and, sometimes, winches. The loads created by the spinnaker can be heavy and variable.

For the cruising sailor, the chief advantage of the ASYMMETRICAL SPINNAKER is that so much of this spinnaker gear is eliminated. Asymmetry does away with the two clews and the sheets that change names. The cruising spinnaker is really a larger, lighter headsail that is tacked and jibed much the same way as a normal headsail, but is not attached along the forestay. Instead, it flies freely away from the forestay.

The racing approach to asymmetrical spinnakers is a little different. A pole is still used, but it has become a telescoping bowsprit. The spinnaker is typically not flown directly downwind (because these new, light boats sail fastest by tacking downwind), but is flown like a headsail, even though it is as big and almost as round as a conventional reaching spinnaker.

BASIC SAIL TRIM

With practice, and by noting the results during trial and error experimentation, helmsman and crew will develop a feel for a boat’s characteristics in different conditions and take appropriate measures to keep it “in the groove.” Sail trim is a major component of achieving that goal, whether or not you are racing. The following are some elementary aspects of sail trim on each point of sail.

Sail Shape

To some degree, the shape of a sail is restricted to the amount of camber designed into it by the sailmaker. But the depth of the camber (DRAFT) can be controlled, and the position of the deepest part of the draft, with respect to the luff of the sail, can also be controlled; see Figure 8-15. A more familiar, and eminently changeable, element of sail trim is the angle of attack—the angle at which the sail meets the apparent wind.

As discussed in the preceding section on sailboat parts, a host of controls is available for trimming and shaping the sails for the conditions encountered. Be forewarned, however: There are no hard and fast rules for the order or degree with which each is used. Observation of the telltales on the sails and instruments in the cockpit, ability to hold a desired course, and the “feel” of the helm all measure the success of each action or combination of actions. Moreover, actions that produce a positive response on one boat may not produce the same response on another. But if experimentation is the rule of sail trim, there are some fundamentals worth learning.

Figure 8-15 Changing the shape of a sail is accomplished by changing the depth of the draft to produce a flatter or fuller sail. The amount of draft required in different conditions varies with the point of sailing. In general, flatter sails (upper) are more efficient upwind than fuller ones (lower).

Mainsail Trim

Changing the shape of the mainsail involves changing the depth of the draft to produce a flatter or fuller sail. Moving the mainsail’s draft forward or aft is also a factor in improving the balance of the boat. Most of the time, the ideal position for maximum draft is one-third to one-half the way back from the mast. When sailing upwind, the object is to make the sail fuller at the leading edge, to direct total lift force forward and reduce side forces. When reaching, draft position is usually farther aft. Tensioning the clew outhaul to pull the clew aft reduces draft and moves it forward. The same effect is achieved by tensioning the backstay and boom vang to bend the top of the mast aft and bow the middle of the mast forward. As the mast bows forward, it pulls the middle of the mainsail and flattens it out; see Figure 8-16. Increasing halyard tension and taking up on the cunningham are also effective measures to move draft forward.

Figure 8-16 Using the backstay to tension the top of the mast aft will bow the middle of the mast forward, and so flatten a mainsail. The effect is to reduce draft and move it forward.

The mainsheet, combined with the boom vang and traveler, controls the tension on the leech of the mainsail. Leech tension is important for several reasons, but the two principal considerations are twist and trailing-edge shape.

In general, wind flows faster with increasing height above the water. That means that the top of a sail should be trimmed to a different angle than the bottom, with the greater angle at the top—hence sail twist; see Figure 8-17.To achieve a high degree of twist, you would usually ease the mainsheet, allowing the boom to rise. You might have to pull the traveler car to windward to prevent the boom from swinging too far from the boat’s centerline. The boom vang would be slack.

Figure 8-17 Because wind speed is greater aloft than at deck level, sails need to be trimmed to a wider angle at the top than at the bottom. Sail twist is achieved by easing the mainsheet, allowing the boom to rise (far left). To remove twist (near left), trim the mainsheet in, and use the traveler to position the boom slightly farther off the boat’s centerline.

The opposite effect, removing twist, is achieved by trimming harder on the mainsheet, placing more tension up the leech, easing the traveler car to leeward to position the boom somewhat away from the boat’s centerline, and using a tight boom vang. More pressure is carried high and aft by the mainsail, and the leech “closes up”—begins to push airflow away to windward instead of just letting it flow easily aft.

While the coarse setting of leech tension might be matched to the average wind strength and the point of sail, gusts and lulls may require further fine-tuning with the mainsheet. Typically, the mainsheet is tensioned in lulls and eased (or even released) to open the leech and depower the sail in gusts. Upwind, the mainsheet usually provides most of the leech control. Off the wind or on a reach, when the main is eased, the vang controls the leech. Many sails also have a LEECHLINE and a small cleat built into them to provide fine control as an adjunct to the coarse control of the mainsheet and vang. Care must be taken that the leechline is not so tight as to hook the leech to windward.

The traveler, of course, provides a means of balancing the mainsheet’s vertical and horizontal pull on the boom. As the mainsheet is eased and the boom moves to leeward, the angle of pull on the boom becomes more horizontal, removing tension from the leech. When the traveler car is eased to leeward, the pull of the mainsheet becomes more vertical, increasing leech tension.

The traveler car can also be pulled to windward in light air so that the mainsheet tension remains more horizontal when the boom is close to or right over the centerline of the boat. This allows sufficient twist with a smaller angle of attack. However, care must be taken not to overtrim the main. A rule of thumb is to keep the batten second from the top parallel to the boom; no battens—in fact, no part of the sail—should ever point to windward.

THE POINTS OF SAILING

When a boat is sailing as close as it can to the direction from which the wind is blowing, the boat is said to be “close-hauled,” meaning that its sails are hauled in close to the hull. Another name for this is “beating.”

When the angle between heading and wind direction is increased, the boat begins to “close reach,” and when the angle is about 90°, the wind is on the beam, so the boat is “beam reaching.”

Further increases in angle bring the boat to a “broad reach”; with the wind almost directly aft, the boat is “running.”

The term “running” sounds fast, and in square-riggers, it may well have been. But the fastest point of sail for most modern boats is a close reach, and running is slow by comparison.

Remember that this diagram shows the relation between a boat and the true wind, while the more important factor, especially for today’s faster boats, is the relationship between a boat and its apparent wind—the wind that the sails feel. Very fast boats, like catamarans and racing dinghies, might seem to be swinging from a close reach right through to a broad reach in terms of the true wind, when they are in fact close reaching the apparent wind. Sails are trimmed to the apparent wind, not the true wind.

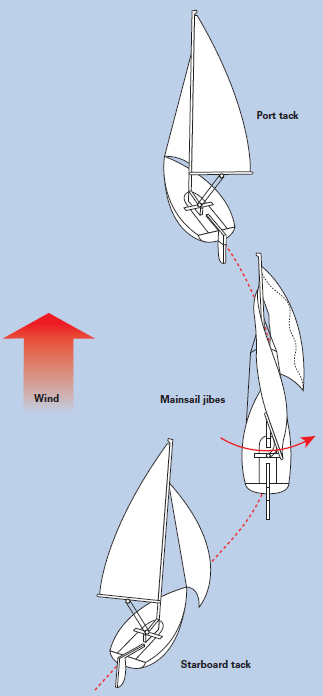

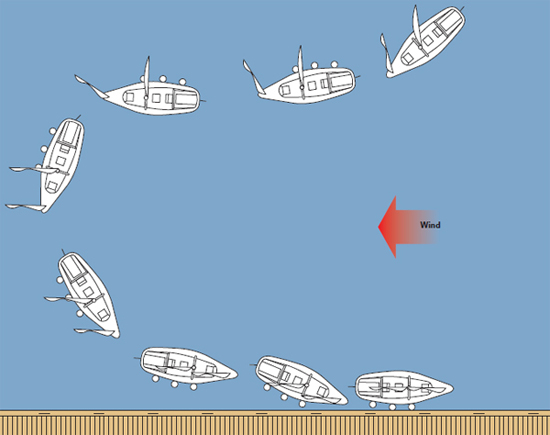

A sailboat cannot sail directly into the eye of the wind, but modern sailboats can sail to within 45° of the wind, or closer, when close-hauled. A reach is the fastest point of sail, with the sails eased partway out. A run is aerodynamically simpler but can be the most dangerous point of sail. The sails are extended as far out over the sides of the boat as possible and can swing across with tremendous force.

Headsail Trim

The headsail, or jib, of many boats supplies as much drive as the main, or more. Not only are headsails often as large as the main, especially in masthead rigs with genoas, but the sail is presented to a clean airflow that is undisturbed by mast windage.

The tension on the forestay is the second most important control of the headsail shape after sheet position and tension.

A loose forestay (created by loosening the backstay) creates sag, which in turn creates a full (deep draft) headsail. Sailmakers build a degree of allowance for forestay sag into the sail shape, but increasing tension in the forestay has the same effect as straightening the mast: The sail is pulled tighter across the middle and becomes flatter.

Upwind, particularly in brisk winds, the jib halyard should be tensioned in order to keep the position of the deepest part of the draft as far forward as possible.

Key to trimming the jib, however, is the position of the clew. As the leeward sheet is eased, the clew will tend to move outboard and upward. The effect is a fuller sail. Tensioning the sheet pulls the clew aft, down, and inboard, flattening the sail and decreasing the angle of attack with the airflow.

Twist in the headsail is controlled by the position of the sheet lead (also known as the fairlead). As the lead is moved forward, the sheet pulls more on the leech—more downward. But as the lead is moved aft, the sheet pulls more on the foot—more backward.

In practice, it is often difficult to see the angle of the jibsheet accurately. But if the leech is fluttering, it indicates that the fairlead is too far aft, creating too much twist at the top of the sail; if the foot of the sail is fluttering or bellied out too far, the fairlead is too far forward, flattening the top of the sail too much.

Telltales

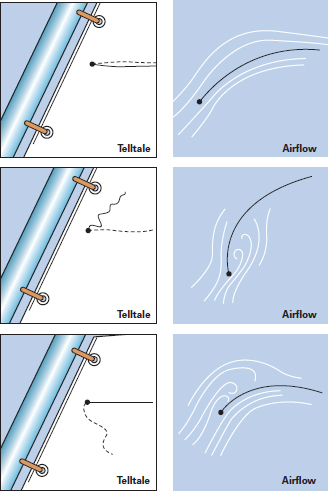

The most effective sail trim is often elusive, even for experienced sailors. Yet while no one can actually see the wind, there remains a relatively simple solution: Place pieces of ribbon or yarn about eight or nine inches long—telltales—at or near the luff on both sides of the headsail, and sometimes also on the mainsail. Their movement will reveal the action of the wind; see Figure 8-18. Jib telltales can serve to fine-tune sheet lead position and sheet tension. Although telltale positions will vary with preference, in general three telltales are placed on the jib about a foot behind the luff so that they divide the luff into four roughly equal sections. (It’s a good idea to avoid placing telltales too close to seams. It can be frustrating when they become caught on stitching in light air.)

Some sailors also favor telltales at the point of maximum draft on their mainsail, and one at each batten pocket along the leech, in addition to three telltales at the luff positioned as for the jib. Headsail luff telltales are uniquely useful because they “read” undisturbed airflow.

In general, the object when trimming a sail or steering close-hauled is to have all the telltales streaming aft at the same time, indicating that the airflow across the two sides of the sail is even and smooth. If the leeward jib telltales are lifting or fluttering, they indicate that the boat can be steered closer to the apparent wind because the airflow is hitting the edge of the sail and tipping over it, resulting in a curl. If it is not necessary or even desirable to steer closer to the wind—if the boat is not sailing upwind, but reaching—the same corrective effect can be achieved by letting the sail out. The leading edge of the sail thus meets the airflow more smoothly, and as a consequence the telltales stream aft.

Conversely, if a windward jib telltale lifts and flutters, the boat is too close to the apparent wind and must be LAID OFF, or steered at a wider angle to the apparent wind. If a course change is not desirable, the airflow can be corrected by pulling the sheet tighter and the sail closer to the boat’s centerline.

If the telltales nearer the foot of the sail (usually the headsail) are acting differently from the telltales nearer the head, then there is something wrong with the amount of twist. The sheet lead position should be changed until the telltales all react in a similar manner to changes in steering angle or sheet tension. For example, if the upper windward telltales are lifting while the lower ones are streaming, this is an indication that the sail has too much twist and the leads should be moved forward.

Fluttering or drooping telltales on the leech of the mainsail indicate that the air leaving the after edge is curling, creating drag; this is created by loosening of the leech tension, known as OPENING UP THE LEECH. This drag can be reduced or eliminated by tightening the leech.

Figure 8-18 Telltales on a sail’s luff stream aft on both sides of the sail (dashed line is to leeward) when airflow is even and smooth (upper). A lifting windward telltale when you’re sailing close-hauled (middle) indicates that you’re pinching (heading too close to the wind). A stalled or fluttering leeward telltale (lower) indicates that you’re not heading high enough.

The Slot

The mainsail and the headsail work very closely together to shape the air that flows between them. This area between the sails is called the SLOT. The headsail accelerates the air across the leeward surface of the main, helping it produce lift and substantially enhancing the low-pressure venturi effect.

If the jibsheet is eased, it permits the clew to rise and go too far outboard. The slot may become too open, so that there is no accelerated flow. If the jib is sheeted too tightly, the slot closes and the jib forces airflow to curl into the back of the main—BACKWINDING the main and destroying the low pressure that is the whole object of the trimming. (Sometimes this backwinding is acceptable if there is too much airflow and sufficient power is being taken from the headsail while the main acts to balance the pressures fore and aft to control steering.)

The jib should generally be trimmed for course and conditions first, then the main trimmed so that the twist of its leech matches that of the jib, making the slot effective. On an upwind course, jib and main are usually trimmed as close to the centerline as wind force will permit. On some boats, a second fairlead track, or BARBER-HAUL system, permits the headsail sheet lead to be positioned closer to or farther from the centerline, as well as fore and aft, with much the same effect as adjusting the mainsheet traveler.

Other Rigs

When measured against the relatively complex rigging of conventional sailboats, the popularity of wishbone cat rigs is easy to understand; see Figure 8-19, far right. One sail does all the work and is controlled, for the most part, by one line—the mainsheet. The wishbone boom is suspended at its forward end by a choker line that attaches to a block on the mast and leads down to the foot of the mast and back to the cockpit. At its aft end, it is suspended, like a conventional boom, by the sail. The tightness or looseness of the choker line determines the depth or shallowness of the curve of the main in somewhat the same way that a conventional outhaul does.

Very small sailboats may have a variety of rigs, as shown in Figure 8-19.

Figure 8-19 Very small sailboats may have a variety of rigs as shown here. Most commonly seen is the lateen rig, used on board boats such as the Sunfish, and the wishbone rig used on board sailers. The rigs shown above are in addition to the common Marconi and gaff rigs.

Upwind Techniques

The closer to the wind a boat sails, the less distance it must travel to reach an upwind destination. But it also sails slower. Conversely, the farther off the wind it sails, the faster the boat moves. But it must sail a greater distance; see Figure 8-20.

The objective of sailing upwind (variously called POINTING, BEATING, or SAILING CLOSE-HAULED or TO WEATHER) is to reach a specific point as quickly as possible by sailing a course that strikes the best compromise between higher speed and longer distance on the one hand, and lower speed but shorter distance on the other. The exact best compromise changes with wind speed and wave conditions.

In general, flatter sails are more efficient upwind than are full ones; refer to Figure 8-15. They also should be sheeted as close to the centerline as the wind strength will allow. The crew should be prepared to depower sails during gusts—either by easing the traveler car to leeward or by easing the mainsheet—so that excessive heeling doesn’t contribute to leeway. Positioning crew to windward and even asking them to hike over the side will also help to counter heeling, thus allowing the keel to produce more lift and less leeway.

Constant adjustment of sails is called for in alternating gusts and lulls when close-hauled. Alternatively, the helmsman can PINCH UP in puffs and gusts, temporarily depowering the sails and keeping the boat ON ITS FEET (albeit at a temporary loss of speed), and BEAR OFF in lulls to accelerate.

Sailing close-hauled, the helmsman must determine how well the boat is balanced. If too much weather helm is required to keep the boat sailing a straight course, the center of effort has moved too far aft or the boat has heeled too much. To balance the boat, the sails can be depowered (flattened), the mainsail leech can be opened up, the boom can be eased out away from the centerline, or all three.

To sail a windward course well, a crew must deal with several trade-offs. Factors such as wind strength, the possibility of a wind shift, sea conditions, strain on the boat, and crew comfort (and in a race, how the competition is doing) must be weighed in order to set a course that efficiently and economically moves the boat toward the target.