Figure 10-01 Reefed, with lee rail awash, this boat is being driven hard in moderate seas.

Boat Handling Under Adverse Conditions • Running Aground • Assisting & Towing Other Vessels

While boaters would all prefer to be out on the water in pleasant conditions, experienced skippers recognize that sometimes there will be bad weather, they may run aground, or they may need to assist another vessel in trouble. They may encounter emergencies such as a man overboard, fire, or the need to abandon a sinking boat. Every skipper should be thoroughly familiar with the special seamanship techniques presented in this chapter, which are required to safely cope with these conditions. The particulars of specific serious situations aboard, such as man overboard, fire, and abandoning ship, are covered in Chapter 12, “Emergencies Underway.”

BOAT HANDLING UNDER ADVERSE CONDITIONS

Perhaps the most important test of a skipper’s abilities comes in how he handles his boat in adverse weather conditions. Boat size has little bearing on seaworthiness, which is fixed more by design and construction. The average power cruiser or sailboat is fully seaworthy for normal conditions in the use for which it is intended. Which means: Don’t venture into waters or weather conditions clearly beyond what your boat was designed for. Remember also that what a boat will do is governed to a great extent by the skill of its skipper; a good seaman might bring a poor boat through a blow that a novice could not weather in a far more seaworthy one.

PREPARATIONS FOR ROUGH WEATHER

In anticipation of high winds and rough seas, a prudent skipper takes certain precautions. No single list fits all boats or all weather conditions, but among the appropriate actions are those listed below. Storms can be a tremendous test of the knowledge, endurance, courage, and good judgment of the skipper and crew. A well-prepared craft and its crew are more likely to survive a storm.

• Keep your boat’s fuel tank or tanks clean. Rough seas can resuspend sludge from the tank bottom, which could clog your fuel filters and kill your engine just when you need it most.

• Break out life preservers and have everyone on board, including the skipper, wear one before the situation worsens; don’t wait too long.

• Secure all hatches; close all ports and windows. Close off all ventilator openings.

• Pump bilges dry and repeat as required.

• Secure all loose gear; put away small items and lash down larger ones, on deck and especially below.

• Break out emergency gear that you might need—hand pumps or bailers, sea anchor or drogue, etc.

• Make sure that navigation lights are working. Hoist the radar reflector if it is not already rigged. Check batteries in flashlights and electric lanterns.

• Get a good check of your position if possible, and update the plot on your chart.

• Make plans for altering course to sheltered waters if necessary.

• If towing a dinghy, bring it on board and lash it down securely.

• If under power, check the engine room, especially fuel filter bowls.

• If sailing, prepare all reefing lines; set up the storm jib and trysail if this can be done independently from the mainsail and headsails. Be ready to change to storm sails quickly. If running before the wind, rig a strong preventer that can be released from the helm. Wear your safety harness at all times; it should fit snugly over your clothing. Especially offshore or at night, a jackline or jacklines should be rigged. That way, in heavy weather, every crewmember on deck can at all times be attached to padeyes, other strong deck hardware, or a jackline via his or her safety harness tether, even (especially!) when working on the foredeck. Being tethered can be inconvenient, but it’s far better than being washed overboard by a boarding sea. Charge your batteries and avoid unnecessary drains on them until the weather improves.

• Remember that being cold can affect a person’s judgment. Have everyone put on appropriate clothing. Choose clothing that will keep you warm even when wet—wool or polypropylene.

• Give all hands a good meal while you have the opportunity; it might be a while until the next one. Prepare some food in advance; put coffee or soup in a thermos, and store something that can be eaten easily and quickly—perhaps sandwiches—in a watertight container.

• Get out the motion sickness pills; it is much better to take them before you get queasy.

• Reassure your crew and guests; instruct them in what to do and not to do, and then give them something to do to take their minds off the situation.

Rough Weather

“Rough weather” is a relative term, and what might seem a terrible storm to the fair-weather boater may be nothing more than a good breeze to an experienced, weather-wise skipper.

On large, shallow bodies of water like Long Island’s Great South Bay, Delaware Bay and River, or Lake Erie, even a moderate wind will cause uncomfortable steep waves with breaking crests. Offshore or in deeper inland water, the same wind force might cause moderate waves or slow, rolling swells and would be no menace to small craft; see Figure 10-01.

Know Your Boat

Boat handling under adverse conditions is an individual matter, since no two boats are exactly alike in the same sea conditions. When the going gets heavy, each hull design reacts differently—and even individual boats of the same class may behave differently because of factors like load and trim.

Each skipper must learn the particulars of his boat to determine how best to apply the principles covered in the following sections. Reading this book and taking courses are important first steps. You can learn basic good seamanship by absorbing facts and principles, but you’ll have to pick up the rest by using your book and classroom learning on the water when the wind blows.

Even when conditions do not force you to undertake special seamanship techniques, involve yourself with theoretical situations. Ask yourself and your crewmembers how to handle various difficulties. While cruising along on a calm day, for example, ask what each person should do if the boat suddenly ran aground. This not only makes for interesting conversation, but also provides a good basis for practicing procedures.

Head Seas

The average well-designed power cruiser or larger sailboat should have little difficulty when running generally into head seas. If the seas get too steep-sided or if you start to pound, slow down by easing the throttle or shortening sail. This gives the bow a chance to rise in meeting each wave instead of being driven hard into it. (A direct consequence of driving hard into a wave could be that the force of the water hitting the superstructure would break ports and windows.)

Match Speed to Sea Conditions

If conditions get really bad, slow down until you’re barely making headway, holding your bow at an angle of about 45° to the waves. The more you reduce headway in meeting heavy seas, the less the strain on the hull and superstructure and the less the stress on the persons onboard.

Avoid Propeller “Racing”

You must reduce speed to avoid damaging the hull or engine if the seas lift the propeller clear of the water and it “races.” This sounds dangerous—and it may be. First, there’s a rapidly increasing crescendo of sound as the engine winds up, then excessive vibration as the propeller bites the water again. Don’t panic—ease the throttle and change your course until these effects are minimized.

Keep headway so you can maneuver your boat readily. Experiment to find the speed best suited to the conditions.

Adjust Trim

You can swamp your boat if you drive it ahead too fast or if it is poorly trimmed. In a head sea, a vessel with too much weight forward will plunge rather than rise. Under the same conditions, too much weight aft will cause it to fall off. The ideal speed will vary with different boats—experiment with your craft and find out its best riding speed.

Change the weight aboard if necessary. On outboards, shift your tanks and other heavy gear. In any boat, direct your passengers and crew to remain where you place them.

Meet Each Wave as It Comes

You can make reasonable progress by nursing the wheel—spotting the steep-sided combers coming in and varying your course, slowing or even stopping momentarily for the really big ones. Just as you adjust your speed when driving a car on a winding road, you must vary your boat’s speed to get through waves. If the person at the helm can see clearly and act before dangerous conditions develop, the craft should weather moderate gales with little discomfort. Make sure the most experienced person aboard acts as helmsman, with occasional breaks in order to stay sharp.

In the Trough

If your course requires you to run broadside to waves or swells, bouncing from crest to trough and back up again, your boat may roll heavily, perhaps dangerously. In these conditions in a powerboat it is best to run a series of “tacks,” much like a sailboat.

Tacking Across the Troughs

Change course and take the wind and waves at a 45° angle, first broad on your bow and then broad on your quarter; see Figure 10-02. You will make a zigzag course in the right direction, with your boat broadside to the trough only briefly while turning. With the wind broad on the bow, the boat’s behavior should be satisfactory; on the quarter, the motion may be less comfortable, but at least it will be better than running in the trough. Make each tack as long as possible to minimize how often you must pass through the trough.

To turn sharply, allow your powerboat to lose headway for a few seconds, turn the helm hard over, then suddenly apply power. The boat will turn quickly as a powerful stream of water strikes the rudder, kicking you to port or starboard without making any considerable headway. You won’t be broadside for more than a minimum length of time. This is particularly effective with single-screw boats. With twin-screw powerboats, the engine on the side in the direction of the turn may be throttled back or even briefly reversed.

Figure 10-02 This U.S. Coast Guard utility boat is taking waves at a 45° angle to its stern. With skillful use of power and helm, it will remain under control despite the breaking seas.

Running Before the Sea

If the swells are coming from directly behind you, running directly before them is safe if your boat’s stern can be kept reasonably up to the seas without being thrown around off course. But in heavy seas, a boat tends to rush down a slope from crest to trough, and, stern high, the propeller comes out of the water and races. The rudder also loses its grip, and the sea may take charge of the stern as the bow “digs in.” At this stage, the boat may yaw so badly as to BROACH—to be thrown broadside, out of control—into the trough. Avoid broaching by taking every possible action. Unfortunately, modern powerboat design emphasizes beam at the stern so as to provide a large, comfortable cockpit or afterdeck, and this width at the transom increases the tendency to yaw and possibly broach.

Reducing Yawing

Slowing down to let the swells pass under your boat usually reduces the tendency to yaw, or at least reduces the extent of yawing; see Figure 10-03. While it is seldom necessary, you can consider towing a heavy line or drogue astern to help check your boat’s speed and keep it running straight. Obviously the line must be carefully handled and not allowed to foul the propeller. Do not tow soft-laid nylon lines that may unlay and cause hockles (strand kinks).

Cutting down engine speed reduces strain on the motor caused by alternate stern-down laboring and stern-high racing.

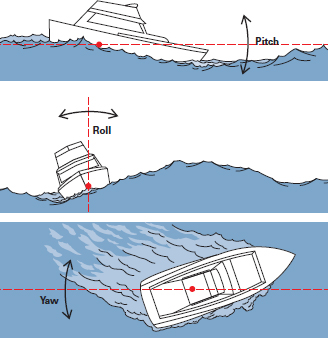

Figure 10-03 Pitching, rolling, and yawing are normal motions of a boat. If they become excessive, or combine, they may be uncomfortable or even dangerous.

Pitchpoling

The ordinary offshore swell is seldom troublesome when you are running before the seas, but the steep wind waves of some lakes and shallow bays make steering difficult and reduced speed imperative. Excessive speed down a steep slope may cause a boat to PITCHPOLE—that is, drive its head under in the trough, tripping the bow, while the succeeding crest catches the stern and throws her end over end. When the going is bad enough that there is risk of pitchpoling, keep the stern down and the bow light and buoyant, by shifting weight aft as necessary.

Shifting any considerable amount of weight aft will reduce a boat’s tendency to yaw, but too much might cause it to be POOPED by a following wave breaking into the cockpit. Do everything in moderation, not in excess. Adjust your boat’s trim bit by bit rather than all at once, and see what makes it more stable.

Tacking Before the Seas

Use the tacking technique also when you want to avoid large waves or swells directly astern. Try a zigzag track that puts them alternately off each quarter, minimizing their effects—experiment with slightly different headings to find the most stable angle for your boat—but keep it under control to prevent a broach.

Running an Inlet

One of the worst places to be in violent weather is an inlet or narrow harbor entrance, where shoal water builds up treacherous surf that often cannot be seen from seaward. Inexperienced boaters, nevertheless, often run for shelter rather than remain safe, if uncomfortable, at sea, because they lack confidence in themselves and their boats.

When offshore swells run into shallower water along the beach, they build up steep waves because of resistance from the bottom. Natural inlets on sandy beaches, unprotected by breakwaters, usually build up a bar across the mouth.

When the swells reach the bar, their form changes rapidly, and they become short, steep-sided waves that tend to break where the water is shallowest.

Consider this when approaching from offshore: A few miles off, the sea may be relatively smooth, and the inlet from seaward may not look as bad as it actually is. Breakers may run clear across the mouth, even in a buoyed channel.

Shoals shift so fast with moving sand that buoys do not always indicate the best water. Local boaters often leave the buoyed channel and are guided by the appearance of the sea, picking the best depth by the smoothest surface and absence of breakers. A stranger is handicapped here because he may not have knowledge of uncharted obstructions and so may not care to risk leaving the buoyed channel. He should thus have a local pilot, if possible, or he might lay off or anchor until he can follow a local boat in.

If you must get through without local help, these suggestions may make things more comfortable:

• Contact the local U.S. Coast Guard station, if there is one, for recommendations. In the absence of a Coast Guard unit, try to contact a local smallcraft towing service, marina, or local fishing boats that frequently use the inlet.

• Make sure your boat is ready—close all hatches and ports, secure all loose gear, and get all persons into lifejackets, briefing them on what to do and what not to do.

• Don’t be in a hurry to run the inlet; wait outside the bar until you have had a chance to watch the action of waves as they pile up at the most critical spot in the channel, which will be the shallowest. Typically, waves will come along in groups of three, sometimes more. The last sea will be bigger than the rest, and by watching closely you can pick it out of the successive groups.

• When you are ready to enter, stand off until a big one has broken or spent its force on the bar, and then run through behind it. Watch the water both ahead and behind your boat; control your speed and match it to that of the waves.

An ebbing tidal current builds up a worse sea on the bars than the flood does because the rush of water out works against and under the incoming swells. If the sea looks too bad on the ebb, it is better to keep off a few hours until the flood has had a chance to begin. As deeper water helps, the very best time is the slack just before the tidal current turns to ebb. Do not use the times of high and low water to plan for the time of slack—these times are rarely, if ever, the same; see Chapter 17 for more on tides and currents.

Departing through inlets is less hazardous than entering, as the boat is on the safe side of the dangerous area and usually has the option of staying there. If you do decide to go out, you can spot dangerous areas more easily, and a boat heading into surf is more easily controlled than one running with the swells. The skipper of a boat outside an inlet may conclude that he has no other choice but to enter, but he should only attempt it in the safest possible manner.

Heaving-To

When considerations get so bad offshore that a boat cannot make headway and begins to take too much punishment, it is time to HEAVE-TO, a maneuver whose execution varies for different vessels. Powerboats, both single- and twin-screw, will usually be most comfortable if brought around and kept bow to the seas or a few points (20 to 35°) off, using just enough power to make bare steerageway while conserving fuel; it may be necessary to occasionally use brief spurts of greater power to keep the craft headed in the best direction.

Sailboats traditionally heave-to with the wheel lashed to keep the boat headed up. A small, very strong STORM JIB is sheeted to windward to hold the bow just off the wind, while a STORM TRYSAIL is sheeted flat. This is a small, strong triangular sail with a low clew and a single sheet; it should have a separate track on the mast so that it can be set up before the mainsail is dropped. A loose-footed sail, it is not traditionally bent to the boom, which is secured in its crutch or lashed down on deck. On a boat with a rigid hydraulic boom vang, however, the trysail can be clewed to the boom and controlled via the mainsheet and traveler. The jib-trysail combination balances the tendency of trysail and rudder to head the vessel into the wind against the effort of the backed jib to head it off, and the result is, ideally, that the boat lies 45° from the wind while making very slow headway.

A flat-cut trysail and a small, flat storm jib set from an inner forestay provide the best balance and ease of handling for heaving-to, but some sailboats will behave acceptably well when hoveto under a double- or triple-reefed mainsail and a heavy, roller-furled jib that’s mostly furled. A full-keeled sailboat will often come to a virtual stop when hove-to, drifting slowly, crabwise, at right angles to the wind. A fin-keeled boat may not heave-to quite as well but may still be far more docile hove-to than when when trying to press ahead on a close reach or close-hauled.

A variation of heaving-to, called FORE-REACHING, is done under deeply reefed mainsail or trysail and a mere scrap of headsail or perhaps none at all. The idea is to jog along on a close reach, meeting the waves as advantageously as possible and maintaining just enough speed through each trough to surmount the oncoming crest.

Lying Ahull

If the wind and seas continue to build, there may come a point when heaving-to is no longer safe. Perhaps the wind is forcing the bow broadside to the waves despite the mainsail and hard-over rudder; perhaps the pressure of wind in sails is heeling the boat uncomfortably far over. It might be time to try LYING AHULL. All sail is dropped and secured, the helm is lashed to prevent damage to the rudder, and the vessel is left to find its own way. This tactic can afford the crew some much-needed rest on the open sea, but most boats will drift broadside to the seas when left unattended. Thus, when the wind is strong enough to raise breaking seas, it may be time to stop lying ahull and instead try lying to a sea anchor or—if there is ample sea room to leeward—running off before the storm, perhaps while trailing a drogue.

Sea Anchors

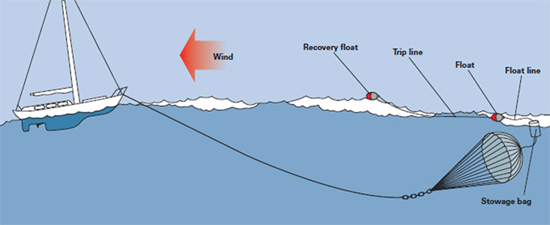

In extreme weather you may use a SEA ANCHOR, traditionally a heavy fabric cone with a hoop to keep it open at the mouth; it appears much like a megaphone. Its leading edge has a bridle of light lines leading to a fitting attached to a heavier towing line. The apex of the cone has a small, reinforced opening to allow a restricted amount of water to pass through from the wide end; see Figure 10-04. Sea anchors may also be a series of plastic floats that fold compactly for storage and are said to be more effective than the traditional kind. Newer designs borrow their general shape from aircraft parachutes. Some have lightweight canopies much like a parachute, while others use a lattice of webbing.

Sea anchors range in size from a few feet to 40 feet (1 to 12 m) or more in diameter depending upon the style of the sea anchor and the size and weight of the craft; they are more common on sailing craft than on powerboats. The bigger the diameter, the more effective a sea anchor will be. Whatever style of sea anchor you carry, test it in moderate weather a few times to make sure it is big enough to be effective. A small one may be easier to stow, but there’s no point to having it if it won’t do the job.

The line that attaches a sea anchor to the boat should be the same diameter as the rode for the craft’s conventional working anchor. A lightweight trip line attached to the smaller end allows the sea anchor to be pulled back to the boat, always an easier task than pulling the boat up to the sea anchor.

Improvised Sea Anchors In the absence of a regular sea anchor, try any form of drag rigged from spars, planks, canvas, or other material at hand that will float just below the surface and keep your boat from lying in the trough.

Figure 10-04 The towline of a traditional sea anchor is made fast to the eye in the bridle (upper right). A trip line is fastened to the apex of the cone; this end has a small opening to let some of the water flow through.

Using a Sea Anchor

The classic use of a sea anchor is to hold the bow of a boat to within a few points of the wind and waves as it drifts off to leeward when it is not making way through the water on its own power. A sea anchor is not meant to go to the bottom and hold, but merely to present a drag that keeps the boat’s head up; see Figure 10-05. A sea anchor will usually float just beneath the water’s surface. It should be streamed at least one wavelength away from the vessel, although the proper length may change with the circumstances. Chafing must be carefully guarded against; a short length of chain used where the rode comes on board is one solution. Such a sea anchor can reduce drift up to 90 percent, but that much reduction can cause the boat to take considerable punishment from wave action. Holding position, however, can save a vessel that has lost power off a lee shore (a shore to leeward of her). If engine repairs are possible, they are much more easily and quickly accomplished if the vessel is head to the seas rather than rolling in the trough. Another use is to allow a crew to rest after hours of battling a major storm at sea.

When retrieving a sea anchor, motor very slowly up to the recovery float (refer to Figure 10-05), taking in the rode so as to not foul the craft’s propeller. Pick up the float and trip line with a boathook.

Figure 10-05 When using a parachute sea anchor, let out lots of rode, as this system relies heavily on the stretch of the nylon line for yielding to the seas (and not standing up against them). Even in moderate conditions, you should pay out at least 200 feet (60 m) of rode; use 10 to 15 times the length of the boat in heavy weather conditions.

Drogues

A close relative of the sea anchor is the DROGUE, which is towed astern to keep a craft from yawing extremely or broaching. A drogue may look something like a sea anchor, but with a larger vent opening to provide a lesser drag, because it is for use on a boat making way through the water. The Galerider drogue has a coarse web contruction to let seawater through, and the Jordan series drogue comprises dozens of small cones (the exact number depending on boat size) spaced along a rode to dampen accelerations down a wave face while yielding to overtaking waves. Unlike riding to a sea anchor, running before a storm while trailing a drogue is an active tactic, requiring someone at the helm. It also requires ample sea room to leeward, but monohull sailboats, especially those with fin keels, may do better running before a gale than riding to a sea anchor. A drogue must be secured ahead of the rudderpost in order to keep the boat maneuverable.

Cautions

Setting a sea anchor that is too small will allow the boat to drift backward at a too-rapid rate. This backward movement may result in damage to the rudder, especially on sailboats, or allow the boat to yaw and possibly fall off into a broach. One rule of thumb for sizing a cone-shaped sea anchor is to have the larger end one inch in diameter for each foot of the craft’s length at waterline (LWL). With parachute-type sea anchors, it is best to follow the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Whether streamed off the bow or stern, all types of sea anchors and drogues put a tremendous strain on a boat, which must be strongly built to withstand any waves that may pound on deck. Sailboats towing a drogue astern must have a watertight, self-draining cockpit with fast-draining scuppers. This prevents seawater from getting into the interior of the boat should it be pooped by a wave breaking over the stern and into the cockpit. Sport-fishing models of powerboats are not designed to survive being pooped, so towing a drogue astern of such craft cannot be recommended.

There is controversy over the safety and efficacy of sea anchors, especially in survival conditions offshore. Modern fin-keel sailboats may not lie quietly to a sea anchor off the bow without a small steadying sail. Such a sail may also keep a powerboat from “dancing” on its rode. Any boat that does not ride well to its anchor or mooring in harbor is unlikely to ride well to a sea anchor. Multihull sailboats seem to ride more successfully to a sea anchor than monohulls.

Sea anchors work only if there is sufficient sea room, because they do permit a steady drift to leeward. When a vessel is driven down onto a lee shore, it must use its regular ground tackle to ride out a gale. It is imperative that constant watch be kept to guard against dragging toward a lee shore. Use your engine to ease the strain during the worst of the blow, and give the anchor a long scope for its best chance to hold. Don’t confuse “lee shore”—a shore onto which the wind is blowing, a dangerous shore—with being “in the lee”—on the sheltered, safer side of an island or point of land.

Other Uses

Sea anchors can also prove useful in less stormy weather. A vessel that loses power in water too deep for conventional anchoring can drift many miles while waiting for assistance. Staying as close as possible to the location of the original distress call greatly assists rescuers; boats that drift from their reported position can be difficult to locate. By limiting drift, a sea anchor can keep a disabled boat in reasonable proximity to the location where rescuers will start their search.

Sport fishermen sometimes use a small sea anchor to slow their boat’s drift over schools of fish. Controlled drift is typically desired by fishermen, so a fishing sea anchor is smaller than one intended for use in an emergency. Commercial fishermen also use them as a means of “anchoring” at sea where depths do not permit normal anchoring; this is useful for resting between periods of fishing activity.

Seamanship in “Thick” Weather

Another “adverse condition” that requires special skills is “thick” weather—conditions of reduced visibility caused by fog, heavy rain or snow, or haze. Fog is the most often encountered and severe of these.

Seamanship in thick weather is primarily a matter of avoiding collisions. Piloting and position determination, the legal requirements for sounding fog signals, and the meteorological aspects of fog are all covered elsewhere in this book (see Contents and Index). Here we will consider only the aspects of boat handling and safety.

Avoiding Collision

The primary needs of safety in conditions of reduced visibility are to see and be seen; to hear and be heard. The wise skipper takes every possible action to see or otherwise detect other boats and hazards, and simultaneously takes all steps to make his presence known to others.

Reduce Speed

You need, of course, to detect other vessels by sight, sound, or radar early enough to take proper action to avoid collision. Both the Inland and the International Navigation Rules require reduced speed for vessels in low visibility—a “safe speed appropriate to the prevailing circumstances and conditions.”

It is best to be able to stop short in time rather than resort to violent evasive maneuvers to avoid a collision. The Navigation Rules require that, except where it has been determined that a risk of collision does not exist (by radar plot, perhaps), any vessel that hears another’s fog signal apparently forward of her beam must “reduce her speed to the minimum at which she can be kept on course. She shall if necessary take all way off, and, in any event, navigate with extreme caution until danger of collision is over.”

Lookouts

Equally important with a reduction in speed is posting LOOKOUTS. This is a requirement of the Navigation Rules, but it is also common sense. Most modern motor- and sailboat designs place the helmsman aft, or fairly far aft, where he is not an effective lookout, so you will probably need one or two additional people on board as lookouts in thick weather.

Look…& Listen

Despite the “look” in “lookout,” such a person is there as much for listening as for seeing; see Figure 10-06. A person assigned as a lookout should have this duty as his sole responsibility while on watch. A skipper should certainly post a lookout as far forward as possible when in fog, and, if the helmsman is at inside controls, another lookout for the aft sector is desirable. Lookouts should be relieved as often as necessary to ensure their alertness; if the crew is small, an exchange of bow and stern duties will provide some change in position and relief from monotony. If there are enough people on board, a double lookout forward is not wasted manpower, but the two should take care not to distract each other.

Figure 10-06 Navigating in fog is one of the greatest tests of seamanship.

A bow lookout should keep alert for other vessels, listen for sound signals from aids to navigation, and watch for hazards like rocks and piles, breakers and buoys. Note that in thick weather, aids to navigation without audible signals can become hazards. A lookout aft should watch primarily for overtaking vessels, but he may also hear fog signals missed by his counterpart on the bow.

The transmission of sound in fog is uncertain and tricky. The sound may seem to come from directions other than the true source, and it may not be heard at all at otherwise normal ranges. See the discussion of fog signals in Chapters 5 and 14.

Stop Your Engine

When underway in fog in a boat under power, slow your engines to idle or shut them off entirely, at intervals, to listen for fog signals from other vessels and from aids to navigation. This is not a legal requirement of the Navigation Rules, but it is an excellent practice.

In these intervals, keep silence on the boat so you can hear even the faintest signal. The listening periods should be at least two minutes to conform with the legally required maximum intervals between the sounding of fog signals. Don’t forget to keep sounding your own signal during the listening period—you may get an answer from close by! Vary your timing to avoid being in sync with the signals of another vessel.

When proceeding in fog at a moderate speed, slow or stop your engines immediately any time your lookout indicates he has heard something. The lookout can then have the most favorable conditions for verifying and identifying what he believes he has heard.

Radar & Radar Reflectors

Radar has its greatest value in conditions of reduced visibility. If your craft has a radar, the Navigation Rules—both International and Inland—require that it be used. It must be on a long enough range scale as to give early warning of the possibility of collision, and all targets must be followed systematically. Use of radar, however, is not a substitute for adequate lookouts.

Whether or not you have radar, you should carry a passive radar reflector (see Chapter 16); this is the time to rig it and hoist it as high as possible. This increases the chances of your boat being detected sooner, and at a greater distance, by a radar-equipped vessel (your own radar will not make your craft easier to detect).

Cruising with Other Boats

If you are cruising with other boats and fog closes in, you may be able to take advantage of a procedure used by wartime convoys. Tie onto the end of a long, light line some object that will float and make a wake as it moves through the water. A life ring or a glass or plastic bottle with a built-in handle will do quite well. The object is towed astern with the boats traveling in single file, one object behind each craft except the last; each bow lookout except the first can keep it in sight even though he cannot see the vessel ahead or even hear its fog signal.

Anchoring & Laying-to

If the weather, depth of water, and other conditions are favorable, consider anchoring rather than proceeding through conditions of poor visibility. Do not anchor in a heavily traveled channel or traffic lane, of course.

If you cannot anchor, then perhaps laying-to—being underway with little or no way on—may be safer than proceeding at even a much reduced speed.

Remember that different fog signals are required when you are underway, with or without way on, and when you are at anchor. By all means, sound the proper fog signal and keep your lookouts posted to look and listen for other craft and hazards.

Use Your Radio

In areas of heavy traffic, especially large vessels, some skippers of small fiberglass boats make “Securite” calls on VHF channels 16 and 13 to advise others of their presence.

RUNNING AGROUND, ASSISTING & TOWING

It is an unwritten law of the sea that a boater should always try to render assistance to a vessel in need of aid. This is one of the primary functions of the Coast Guard, of course, but there are plenty of occasions when timely help by a fellow boater can save hours of effort later after the tide has fallen or wind and sea have had a chance to pick up.

Often, giving assistance means getting a towline to another skipper to get him out of a position of temporary embarrassment or perhaps to get him to a Coast Guard station or back to port. The situation can also be the other way around—you may go aground, or a balky motor or gear failure forces you to ask a tow from a passing boat.

In either case, you should know what to do and why. Thus the problems of running aground, and their solutions, will be considered from both viewpoints: being in need of assistance and being the one who renders aid to another vessel.

Running Aground

Running aground is more often an inconvenience than a danger, and with a little know-how and some fast work, the period of stranding may be but a matter of minutes.

If grounding happens in a strange harbor, chances are you have been feeling your way along and so have just touched bottom lightly. You should be off again with little difficulty if your immediate actions do not put you aground more firmly.

If it becomes apparent that you are not going to get free quickly, or if the situation becomes serious because of weather, call the U.S. Coast Guard and report the incident. Unless your vessel or its crew is endangered, do not make this a “Mayday” call; simply call them and report the problem and your location—they will probably refer you to commercial assistance. If you accept commercial assistance, be sure to negotiate the terms (simple tow or salvage) and price in writing before any work takes place.

Right & Wrong Actions

The first instinctive act on going aground is to shift into reverse and advance the throttle in an effort to pull off; this may be the one thing that you should not do. You could damage the rudder or propeller; you might also pile up more of the bottom under the boat, making it harder aground. You may have already sucked mud or sand into the engine cooling system, or if not, you might do so. All of these events are highly undesirable.

First, check for any water coming in; if there is any, stopping the leak takes precedence over getting off. If no water is coming in, or when it has been stopped, and you are in tidal waters, immediately check the state of the tide. If the tide is rising and the sea quiet enough that the hull is not pounding, time is working for you, and whatever you do to assist yourself will be much more effective later than now. If you grounded on a falling tide, you must work quickly and do exactly the right things—or you will be fast for several hours or more.

About the only thing you know offhand about the grounding is the shape of your boat’s hull, its point of greatest draft, and thus the part most apt to be touching. If the hull tends to swing to the action of wind or waves, the point about which it pivots is the part grounded.

Check the water depth around the boat. Deeper water may be to one side rather than astern. You can use a lead line, boathook, or a similar item. Check from your deck all around. If you have a dinghy, use it to check over a wider area. Examine also the point where the water level meets your hull—if your normal waterline is well above the surface, you are more severely grounded than if there is no apparent change. Also check the raw water intake strainers to your engine or engines. Clean them out if clogged with sand, gravel, or mud before using engine power.

Cautions in Getting Off

Consider the type of bottom immediately. If it is sandy and you reverse hard, you may wash a quantity of sand from astern and throw it directly under the keel, bedding the boat down more firmly. Take care also not to suck up sand or mud into the engine through the engine’s raw water intake.

It the bottom is rocky and you insist on trying to reverse off, you may drag the hull and do more damage than with the original grounding.

Also, if grounded forward, remember that reversing a single-screw boat with a right-hand propeller may swing the stern to port and thus push the hull broadside onto adjacent rocks or into greater contact with a soft bottom.

Kedging after Grounding

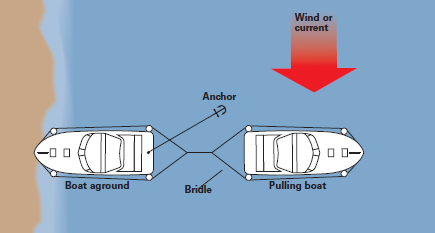

The one right thing to do immediately after grounding is to take out an anchor in a dinghy, if available, and set it firmly, initiating the process of kedging your boat off a shoal; see Figure 10-07.

Unless your boat has been driven very hard aground, the everyday anchor should be heavy enough. Put the anchor and the line in the dinghy, make the bitter end fast to the grounded boat’s stern cleats, and power or row the dinghy out as far as possible, letting the line run from the stern of the dinghy as it uncoils. Whether rowed or powered with the outboard, taking the line out this way will make the dinghy much easier to control than if the anchor rode were dragged from the boat’s stern.

If you do not carry a dinghy, you can often swim out with an anchor, providing sea and weather conditions do not make it hazardous to go overboard. Use life preservers or buoyant cushions—one or two of either—to support the anchor out to where you wish to set it. Be sure to wear a life jacket or buoyant vest yourself, to save your energy for the work. And have a light line attached from you to the boat so that you can be pulled back if you become exhausted.

If there is no other way to get a kedge anchor out, you may consider throwing it out as far as possible. Although this is contrary to basic good anchoring practice, getting an anchor set is so important that it warrants the technique. You may need to throw several times before you get it set firmly.

When setting out the anchor, consider the sideways turning effects of a reversing single screw and, unless the boat has twin screws, set the anchor at a compensating angle from the stern. If the propeller is right-hand, set the anchor slightly to starboard of the stern. This will give two desirable effects. When pulling the anchor line while in reverse, the boat will tend to back in a straight line. When used alternately, first pulling on the line and then giving a short surge with the reverse, the resulting wiggling action of stern and keel can be a definite help in starting the boat moving.

With sailboats, it is often helpful to put out an anchor with a line running to or near the top of the mast. This can be used to heel the boat over, reducing its draft.

Figure 10-07 The first thing to do after going aground is to check hull integrity; next, get a kedge anchor out to keep from being driven farther aground. It may also provide a means of pulling free as waves or the wake from another craft lift your boat.

Getting Added Pulling Power

If you have a couple of double-sheave blocks and a length of suitable line on board, make up a simple WATCH TACKLE (often called a HANDY-BILLY) and fasten it to the anchor line. Then you can really pull! Such a tackle should be part of a boat’s regular equipment.

During the entire period of kedging the boat after grounding, keep the anchor line taut. The boat may yield suddenly to that continued pull, especially if a passing craft throws a wake that helps to lift the keel off the bottom.

Two kedges set out at an acute angle from either side of the stern and pulled upon alternately may give the stern a wiggle that will help you work clear.

If the bottom is sandy, that same pull with the propeller going ahead may wash some sand away from under the keel, with the desired result. If the anchor line is kept taut, try this maneuver with caution.

Move your crew and passengers quickly from side to side to roll the boat and make the keel work in the bottom. If you have spars, swing the booms outboard and put people on them to heave the boat down, thus raising the keel line. Shift ballast or heavy objects from over the portion grounded to lighten that section, and if you can, remove internal weight by loading it into the dinghy or by taking it ashore; pump excess water in your tanks overboard. Unloading a boat is especially practical when running aground at or near high tide—while the tide is going down and coming back up, you have time to unload the heaviest items in order to create more buoyancy.

When to Stay Aground

All of the above is based on the assumption that the boat is not holed. If it is holed, you may be far better off where it lies than you would be if it were in deep water again. If it is badly stove, you may want to take an anchor ashore to hold it on or pull it farther up until temporary repairs can be made.

As the tide falls, the damaged hull may be exposed far enough to allow some outside patching if you have something aboard to patch with. A piece of canvas, cushions, and bedding can all be used for temporary hull patches.

What to Do While Waiting

While waiting for the tide to rise, or for assistance to come, do not sit idle. Take soundings all around you. If circumstances permit, put on a mask and snorkel and take a look. A swing of the stern to starboard or port may do more for you than any amount of straight backward pulling; soundings will locate any additional depth—or, conversely, shallow areas or rocks.

If another boat is present, it may be able to help you even if it cannot pull. Have the other skipper run his boat back and forth to make as much wake as is safely possible. His wake may lift your boat just enough to permit you to back clear.

If your boat is going to be left high and dry with a falling tide, keep an eye on its layover condition. If there is anything to get a line to, even another anchor, you can make it lie over on whichever side you choose as it loses buoyancy. If the boat is deep and narrow, it may need some assistance in standing up again, particularly if it lies over in soft mud. Both the suction of the mud and the boat’s own deadweight will work against it; see Figure 10-08.

If the hull is undamaged and you are left with a falling tide to sit out for a few hours, you might as well be philosophical about it—get over the side and make good use of the time. Undoubtedly you would prefer to do it under happier circumstances, but this may be an opportunity to make a good check of the bottom of your boat or to do any one of a number of little jobs that you could not do otherwise, short of a haul-out.

Figure 10-08 If you go aground on a falling tide, your boat may be left completely “high and dry.” If so, try to brace the boat so that it will stay as upright as possible; it will be easier to refloat.

Assisting a Stranded Boat

If you are not stranded but are able to help another boat that is, you must know what to do and what not to do.

The first rule of good seamanship in this case is to make sure your boat does not join the other craft in its trouble! Consider the draft of the stranded vessel relative to yours. Consider the size and weight of the grounded boat relative to the power of your engines—don’t tackle an impossible job; there are other ways of rendering assistance. Passing close by, making as large a wake as possible, may be all that is needed. Consider also your level of skill—it is often better not to try to be a hero. If you decide that you can safely and effectively assist, follow these guidelines. Otherwise, just stand by until the proper help arrives.

Getting a Line Over

It may seem easiest to bring a line in to a stranded boat by coming in under engine power, bow on, passing the line, and then backing out again, but do not try this until you are sure there is enough water for your boat. Make sure also that your boat backs well, without too much stern crabbing due to the action of the reversed propeller. Wind and current direction will greatly affect the success of this maneuver. If conditions tend to swing your boat broadside to the shallows as it backs, pass the line in some other manner.

Try backing in with wind or current compensating for the reversing propeller, keeping your boat straight and leaving its bow headed out. In any case, after the line is passed and made fast, do the actual pulling with your engines going ahead, to get full power into the pull. For better control over your boat, make the line fast as far forward of the stern as practical.

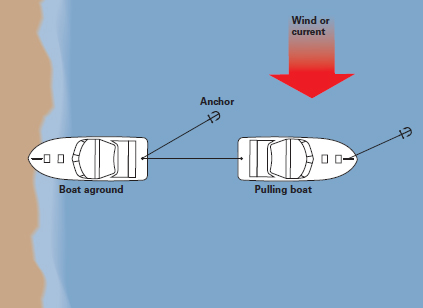

For safe control, you might drop your own bow anchor or anchors, and then send a line over from your boat to the stranded boat; see Figure 10-09. If a close approach seems unwise, anchor your own craft and then send the line in a dinghy, or buoy it and float it over.

Figure 10-09 Most recreational boats pull with the towline cleated astern, which restricts maneuverability. For safe control, put out a bow anchor and take up on its line as the stranded boat becomes free. This arrangement prevents the pulling boat from being carried into shoal water.

Making the Pull

If wind or current, or both, are broadside to the direction of the pull, keep your boat anchored even while pulling and keep a strain on your anchor line. Otherwise, as soon as your boat takes the pulling strain (particularly if the line is fast to its stern), you will have lost maneuverability, which could eventually put your boat aground broadside.

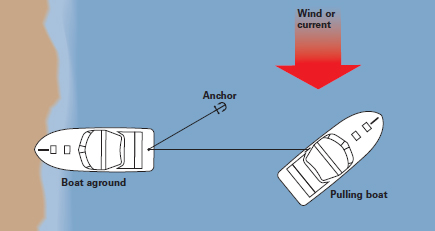

If you are pulling with your boat underway, secure the towline well forward of your stern so that, while hauling, your boat can angle into the wind and current and still hold its position; see Figure 10-10.

Figure 10-10 To aid in maneuverability, if a bow anchor cannot be set, make the towline fast to a cleat forward of the stern on the windward or up-current side of the pulling boat. Be sure that the cleat is capable of taking the heavy strain.

Tremendous strains can be set up, particularly on the stranded boat, by this sort of action, even to the point of carrying away whatever fitting the towline is made fast to. Ordinary recreational craft are not designed as tugboats; the cleats or bitts available for making the line fast may well not be strong enough for such a strain, and they are probably not located advantageously for such work. It is far better to run a bridle around the whole hull and pull against this bridle than to risk damaging some part of the stern by such straining. Use a bridle on your boat, too, if there is any doubt of its ability to withstand such concentrated loads; see Figure 10-11.

When operating in limited areas, the stranded craft should have an anchor out for control when it comes off. It should also have another anchor ready to be put over the side, if necessary, to keep it from going back aground if it is without power. Through all of this maneuvering, keep all lines clear of propellers and make sure no sudden surge is put on a slack line.

Figure 10-11 The best procedure is to put a bridle around the hull or superstructure of both boats in order to distribute the strain over as wide an area as possible. Be sure to pad pressure points to guard against chafing or scarring.

Towing

At some time you will probably need to take another vessel in tow. In good weather with no sea running, the problem is fairly easy. It involves little more than maneuvering your boat into position forward of the other boat, and passing it a towline. (Note that the adage about whose tow-line is used in determining liability in case of an accident is not true.)

Generally speaking, the towing boat should pass her towline to the other craft. You may want to send over a light line first (a plastic water ski towline that floats is excellent), and use that to haul over the actual towing line.

When approaching a boat that is dead in the water to pass it a line, do not be dramatic and move in too close if there is any kind of sea running. Just buoy a long line with several life preservers, tow it astern, and take a turn about the stern of the disabled vessel, but don’t foul its propeller in doing so. The crew of the vessel being assisted can pick the line up with a boathook from the cockpit with far less fuss than by any heave-and-catch method, as long as you are to windward.

The most logical place to attach the line on the boat to be towed is that boat’s forward bitt or cleats, but be sure that such fitting can take the load. The bitt or cleat should be fastened with through bolts of adequate diameter, washers, and nuts—never with self-tapping screws. If the fastening is to the deck, it should be reinforced on the underside with a hardwood or metal backing plate of sufficient area. Even better is a bitt fastened to a major structural member. Be cautious; if an item of deck hardware pulls out under heavy load, the stretched towline can act as a slingshot, hurling the bitt or cleat with great force, enough to cause serious injury or death.

A trailerable boat will have a bow eye that makes an excellent place for attaching a towline; if it is a cast-type bow eye, it could snap off from an improper alignment of the pull. On a small sailboat with the mast going through the deck, wrap the towline around the mast; if the mast is stepped on deck, do not fasten to it—you will only pull it off.

Towing Lines

Three-strand twisted nylon has excessive stretch and dangerous snap-back action if parted under load; it should not be used if its use can be avoided.

Polypropylene line floats and is a highly visible bright yellow, but it has little elasticity, and shock loads are heavily transferred to fittings on both the towed and towing craft. Further, it has less strength (requiring larger sizes), and is stiff, making it difficult to stow and handle; it is also particularly subject to chafing damage. With all these disadvantages, this line, in sizes up to 1/2 inch, is suitable only for light towing loads in protected waters.

The preferred line for towing is double-braided (braid-on-braid) nylon. It has sufficient elasticity to cushion shock loads, but also creates a lesser snap-back hazard. This line is stronger than three-strand twisted nylon of the same size and will not kink. Its disadvantage is that it does not float and must be watched to avoid entanglement in the towing vessel’s propeller. It is the most expensive type of line, but for moderate- and heavy-duty towing it is well worth the cost.

Handling the Towing Boat

The worst possible place to make a towline fast is to the stern of the towing boat, because the pull of the tow prevents the stern from swinging properly in response to rudder action, limiting the boat’s maneuverability. The towline should be made fast as far forward as practicable, as in tug and towboat practice. The deck hardware of the towing boat must be capable of carrying the load—the same as described above for the towed craft. If there is no suitable place forward, make a bridle from the forward bitts, running around the superstructure to a point in the forward part of the cockpit. Such a bridle will have to be wrapped with chafing gear wherever it bears on the superstructure or any corners, and even then it may cause some chafing of the finish.

Cautions in Towing

Secure the towline so that it can be cast loose if necessary, or, failing that, have a knife or hatchet ready to cut it. This line is a potential danger to anyone nearby if it should break and come whipping forward. Three-strand nylon acts like a huge rubber band when it breaks, and there have been some bad accidents. Never stand near or in line with a highly stressed towline, and keep a wary eye out at all times.

On board the towed boat, have an anchor ready to drop in case the towline breaks or must be cast off.

If for any reason you must come near a burning vessel to tow it (for instance, to prevent it from endangering other boats or property), approach from windward so the flames are blowing away from you. Your lightest anchor with its length of chain thrown into the cockpit or through a window of the burning boat could act as a good grappling hook.

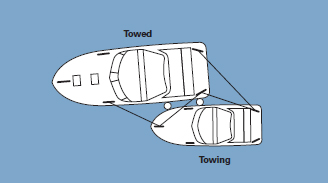

When the towing boat is smaller than the towed craft, it will often encounter heavy resistance from waves hitting the larger vessel; these waves can slow or even stop the progress of the tow. Crosswinds may make you drift off course faster than you are prepared for. One way to avoid these problems is for the towing boat to make fast alongside the towed craft near its quarter; see Figure 10-12. This will make the towing more efficient—even a dinghy with an average outboard motor can usually tow a much larger craft in this manner.

In any towing situation, never have people fend off the other vessel with hands or feet; even the smallest boats coming together under these conditions can cause broken bones or severed fingers. With large vessels, the risk is the loss of a whole limb, or worse.

Never allow anyone to hold a towing line while towing another vessel, regardless of its size. They could receive badly torn tendons and muscles, they might lose the towline over the side, or they could be dragged overboard.

Figure 10-12 Spring lines are used as shown above when a boat takes a larger craft in tow alongside. Fenders are used at points of contact, and springs are made up with no slack. Both boats respond as a unit to the towing boat’s rudder action.

When Not to Tow

Towing can be a dangerous undertaking, as well as an expensive one, if not properly done. If you are not equipped for the job, stand by the disabled vessel. If your craft’s engine would be barely adequate for the task, as in the case of a small sailboat with a small inboard or outboard auxiliary engine, towing another boat in less than perfect conditions might be awkward. You may be able to put a line across and assist by keeping the other craft’s bow at a proper angle to the sea until help comes.

Call the U.S. Coast Guard or other towing agency, and turn the job over to them when they arrive. Don’t try to be a hero, as you are more than likely neither trained nor experienced in this type of work. Remember that the most important concern of a skipper is the safety of persons on board, not the safety of the craft itself. No boat is worth a life!

TOWING PRINCIPLES

Start off easy! Don’t try to dig up the whole ocean, and merely end up with a lot of cavitation and vibration. A steady pull at a reasonable speed will get you to your destination with far less strain on boats, lines, and crewmembers.

• When towing, keep the two boats “in step” by adjusting the towline length to keep both on the crest or in the trough of seas at the same time. Sometimes, as with a confused sea, this may not be possible, but the idea is to prevent a situation where the boat being towed is shouldering up against the back of one sea, presenting maximum resistance, while the towing boat is trying to run down the forward slope of another sea. Then when this condition is reversed, the tow alternately runs ahead briefly and then surges back on the towline with a heavy strain. If there is any degree of uniformity to the waves, the strain on the towline will be minimized by adjusting it to the proper length.

• As the tow gets into protected, quiet waters, shorten up on the line to allow better handling in close quarters. Swing as wide as possible around buoys and channel turns so that the tow has room to follow.

• A small boat in tow should be trimmed a little by the stern; trimming by the head causes her to yaw. In a seaway this condition is aggravated, and it is increasingly important to keep the bow relatively light.

• It is easy for a larger boat to tow a smaller vessel too fast, causing it to yaw and capsize. Always tow at a moderate speed, something less than your hull speed (in knots, 1.34 times the square root of the waterline length in feet), and make full allowance for adverse conditions of wind and waves.

• In smooth water, towing boats may borrow an idea from tugs, which often take their tow alongside in harbor or sheltered waters for better maneuverability. The towing boat should make fast on the other craft’s quarter; refer to Figure 10-12.

• In relatively calm water, even a dinghy with a small outboard motor can tow a medium-size boat at slow speed, enough to get it into harbor or to a pier; tow astern or alongside as required for maneuverability.

Towing Alongside

• Towing alongside may be necessary when the towed craft has lost its steering capability, or when only one person is on board the disabled boat and is using its dinghy to tow. Towing alongside is better than towing astern in congested areas, where maneuvering is more critical.

TRANSFERRING PEOPLE FROM ONE BOAT TO ANOTHER

When it becomes necessary to transfer a person from one boat to another, special seamanship techniques must be employed. The relative size of the craft involved will be a major consideration; transfers at the same height above the water are much easier and safer than when a person must step up or down. The roughness of the water from swells or waves or wakes will also be a major factor. The boat-handling skills of both helmsmen must be taken into account.

A transfer of personnel must not be attempted unless all factors are favorable. The desire of persons to transfer must not be allowed to result in an unsafe action.

Approaches bow-to-bow, beam-to-beam, and stern-to-stern are all possibilities to be considered. Many times, the stern-to-stern technique is desirable if the water is calm enough, particularly if both craft have swim platforms. An additional person should be on each platform to assist the transferee; all of them should be wearing PFDs. The actual transfer should be by stepping rather than jumping; at this time, the engines of both boats should be in neutral. Bow-to-bow and beam-to-beam crossovers are subject to the same general procedures and requirements as above.

It is of the utmost importance that the skippers of the two boats come to full agreement, preferably by radio before the boats come close to each other, as to who does what and when. It is preferable that one craft remain essentially stationary and the other does all the maneuvering. The transfer should not be rushed—if the conditions are not suitable, wait; if an attempt goes bad, back off and try again.