Figure 1-01 Powerboats range from the smallest outboard-powered runabouts to large luxury yachts.

The Language of Boating • The Words That Describe the Vessels, Their Construction, Equipment & Operation • The Terminology That Will Help You Have a Safer, More Enjoyable Time on the Water

Welcome to the Wonderful World of Boating. Whether sail or power, yacht or small boat, cruising, fishing, or just “getting out on the water”—whatever is your style of recreational boating—it can be safer and more enjoyable when done with knowledge. The foundation of any knowledge is built on understanding the special words and phrases of the subject—and so we begin this book.

The language of boats and boating is different from that of the land and landsmen. It has been developed over centuries of use by those who travel the waters, yet is flavored by terms invented in recent memory. When you speak of the “stern” of a boat you are using a word that goes back centuries through several languages; yet when you say that you have a “stern-drive” engine, you are using a term that has been in existence only a relatively short time.

A boater needn’t be excessively “salty” in his speech, but there are strong reasons for knowing and using the right terms for objects and activities around boats. In times of emergency, many seconds of valuable time may be saved when correct, precise terms are used for needed actions or equipment. In correspondence and other written material, use of the right word often shortens long explanations and eliminates doubt or confusion.

Learning and using proper nautical terms will mark you as one who is truly interested in boating. Above all, forming the habit of thinking directly in nautical terms, not in “shore” terms with mental translation, will help you use the proper words consistently. Soon you will find them coming naturally.

The terms discussed in this chapter are not all-inclusive for the field of boating. No two “experts” would agree on what constitutes a “complete” list, and any such list would far exceed the space available here. What follows is intended as a basic nautical vocabulary to prepare you for the various topics presented in detail in succeeding chapters. Many terms will be covered more fully later in the book, and more specialized words and phrases will be introduced at that time. Terms in this chapter will be described in simple, brief remarks rather than comprehensively defined as in dictionaries. Nautical glossaries are available from marine bookstores for those who prefer exhaustive definitions; a Glossary of Selected Terms, Appendix G, is also provided at the end of this book.

BASIC TERMS

Some terms apply to all sizes and types of waterborne vessels; others apply to smaller craft. Many have found their way into everyday language on shore, such as “making headway” to indicate that progress is being made on a task or project.

What Is a Boat?

The term boat has no single definition but generally connotes a waterborne vehicle smaller than a ship. Archaically, a boat was thought of solely as a small craft, such as a lifeboat, carried on board a ship. For purposes of the Navigation Rules, a boat is considered as being no more than 20 meters (65 feet) in length; see Chapters 4 and 5. Other maritime regulations classify a vessel as a boat on the basis of its use, not its size; see page 61 for more on this.

The terms CRAFT or SMALL CRAFT are often used interchangeably with “boat.”

VESSEL is a broad term for all waterborne vehicles and is used without reference to size, particularly in maritime laws and regulations. A YACHT is a power or sail vessel used for recreation, as opposed to work. The term often connotes luxurious accommodations, and it is usually not used for craft under 40 feet (12.2 m) in length, but there are no formally established limits. A newer term, MEGAYACHT, is now being used for yachts 80 feet (24 m) or more in length, while SUPERYACHT is used for those longer than 150 feet (46 m).

Although more and more people refer to boats with the neuter pronoun “it,” the traditional “she” is also correct in speaking or writing about almost any type of vessel. Both words are used throughout this book to refer to boats and other vessels.

Categories of Boats

Boats may be subdivided into POWERBOATS, SAILBOATS, and ROWBOATS as determined by their basic means of propulsion; MOTORBOAT is a term used interchangeably with powerboat; these may have gasoline, diesel, or even electric engines or hybrid systems. Sailboats with AUXILIARY ENGINES are often called AUXILIARIES, and are legally considered to be motorboats when propelled either by engine alone or by both engine and sails simultaneously. A MOTORSAILER is a boat in which sails are used, but their area is reduced and the engine power is increased; these are somewhat less efficient under sail than sailboats and slower under power than motorboats. Some pure motorboats, such as the popular TRAWLER type, have one or more STEADYING SAILS; this is not for propulsion but rather for an easier ride in rough seas or at anchor. Within the broad paddleboat category are such craft as CANOES and KAYAKS.

Figure 1-02 Sailboats get their propulsion from the force of the wind on their sails. They may also have auxiliary engine power for use in calms or for close-quarters maneuvering.

Figure 1-03 A motorsailer is a sailboat that has a larger engine than the typical auxiliary; it can take advantage of both sail and powered propulsion, but with some sacrifice of efficiency in both modes.

The term CRUISER indicates a type of boat with at least minimum accommodations and facilities for overnight trips. The type of propulsion may be added to form such terms as OUTBOARD CRUISER or INBOARD CRUISER. The term is also applied to many sailboats to distinguish them from others designed primarily for racing or daysailing. HOUSEBOATS include both cruising craft whose superstructure is larger and designed more for living aboard, and many smaller vessels that appear to have evolved from land trailers and mobile homes. Houseboats offer more living space than cruisers do, but generally at some sacrifice of seaworthiness and rough-water cruising ability.

A DINGHY (often contracted to “dink”) is a small open boat carried on or towed by a larger craft; it may be propelled by oars, sails, or an outboard motor. A TENDER is a dinghy or a larger LAUNCH used to carry persons and supplies to and from large vessels. A PRAM is a small, squarebow vessel often carrying a single sail.

HYDROFOIL BOATS move on below-hull structures called FOILS that are scientifically designed to give lift, much like the wings of an airplane, when moving through the water at high speeds. The lift force developed by the foils can be sufficient to raise the boat’s hull clear of the water, significantly reducing drag and thus increasing speed.

Figure 1-04 Windsurfing on a sailboard is popular among the young and fit. Skilled sailors can reach 20-to 30-knot speeds in moderate winds.

A SAILBOARD is basically a large surfboard with a mast and small sail. The sail is partially supported by the person standing on board, who steers by shifting the positions of the sail and his or her weight on the board; see Figure 1-04.

Most boats have only a single main body or HULL, but others may have two or three, and are known collectively as MULTIHULLS. Among these latter types are CATAMARANS with two hulls, which may be identical or mirror images of each other; see Figure 1-05. TRIMARANS have three hulls; a larger center one and two smaller outer hulls. Originally, almost all multihulls were sailing craft, but recent years have seen an increasing interest in power catamarans in a wide range of sizes.

Figure 1-05 Boats, power or sail, with two hulls are called catamarans. They have additional stability and a good measure of speed. Craft with three hulls—the center one usually much larger than the outer ones—are termed trimarans.

INFLATABLE BOATS are usually associated with tenders of less than 10 feet (3 m), but they can be much larger. Inflatables of 25 feet (7.6 m) or longer are occasionally seen. A major advantage of inflatables as tenders is that they can be deflated and stowed in a small space. In this mode they often double as life rafts, though they lack many of the protective features that are associated with a proper life raft (Chapter 3).

Inflatables provide greater capacity and more stability than conventional tenders of similar length. Their soft inflated tubes spare the finish of the main hull when the tender is alongside. Unfortunately, they can be difficult (if not impossible) to row under windy or choppy conditions, so are usually powered with a small outboard motor.

Primary considerations with inflatables are the quality of the fabric and gluing process used in their construction. High-quality fabrics that resist abrasion and sunlight and high-strength seams are expensive; consequently, more durable boats are more costly than ordinary inflatables of similar size. For safety, any inflatable should have two or more separate air chambers. If damage causes one to deflate, the undamaged chamber or chambers will keep the boat afloat.

Inflatable and conventional boat construction are combined in what is called a RIGID INFLATABLE BOAT or RIB. RIBs are built with a two-part hull, the lower closely resembling the bottom of a high-speed fiberglass powerboat and the upper consisting of inflated tubes. This gives RIBs both the efficient, high-speed performance of a conventional powerboat and the great stability of an inflatable; see Figure 1-06. Such craft can be rowed with much greater ease and success than “soft” inflatables. Many RIBs are purchased not as tenders but as primary boats.

Figure 1-06 Inflatable boats with rigid hulls, often called RIBs, are used both as dinghies and as sportboats. They combine the benefits of a conventional hull with the flotation and stability characteristics of an inflatable.

PERSONAL WATERCRAFT, usually referred to as PWCs, have become widely popular both for owners and as rental boats. There are numerous definitions of the term, all of which vary slightly but do not seriously conflict. The PWC Industry Association coined the term and defined it as “an inboard vessel; less than 4 meters (13 ft) in length that uses an internal combustion engine powering a water jet pump as its primary source of propulsion, and is designed with no open load-carrying area that would retain water”; see Figure 1-07. “The vessel is designed to be operated by a person or persons positioned on, rather than within, the confines of the hull.” (Organizations of manufacturers and users of canoes and kayaks are disputing this definition, claiming that their boats are also “personal watercraft.”) A PWC might be considered a motorcycle on the water—the operator sits astride or stands and controls the craft using a handlebar with a throttle on one of the grips. Many models can carry one or two additional persons seated behind the operator. They are often referred to by the brand names of the principal manufacturers—Jet Ski, Wave Runner, or Sea-Doo. It is important to note that PWCs are “vessels,” and must be registered similarly to other boats and are subject to all the same equipment requirements, navigation rules, etc., as other boats. They are intended for use only during daylight hours; they can be operated legally only between sunrise and sunset as they are not equipped with navigation lights.

Figure 1-07 A personal watercraft, usually called just a PWC, is much like a motorcycle on the water—the operator “rides” the PWC by standing or sitting behind a set of handlebars with a throttle grip. PWCs are, however, a “vessel” and must comply with all navigation rules and other regulations relating to boats.

JET BOATS are a development from PWCs. Similarly propelled by a water jet, they are larger, usually with seating for about four persons; those on board sit inside the hull and remain dry. They are usually fitted with navigation lights that allow their use after dark.

A JET DRIVE is a form of water-powered propulsion found more and more often in larger powerboats.

WAVE-PIERCING CATAMARANS

The native peoples of the South and Southwest Pacific have built and used multihull craft for centuries. Thus it is not unexpected that the newest concept in catamarans has developed in Australia and New Zealand. This is the WAVE-PIERCING CATAMARAN, a design that offers a number of advantages, the principal one of which is described by its name—the vessel quite literally pierces oncoming waves rather than riding up and over them.

The basic design typically has the appearance of a normal deep-V hull held just clear of the water surface by a pair of DEMI-HULLS; these are long, narrow shapes with quite sharply pointed bows, their tops just above the water. They penetrate the waves, and the vessel as a whole rides much more steadily with less pitching motion. Large waves may come up as high as the bow of the main hull, but its deep-V design cuts easily through their tops. (Some variations in design appear more like a conventional catamaran with a broad structure tying the two demi-hulls together high above the water.) A wavepiercing catamaran can maintain a much higher speed than a conventional catamaran when the going gets rough.

Boaters & Yachtsmen

The owner-operators of recreational small craft, whether male or female, can be referred to as BOATERS. He or she also may be called, informally, the SKIPPER or CAPTAIN; the usual legal term is “operator.” The designation of YACHTSMAN is typically reserved for owners of larger craft. Others on board are CREW if they participate in the operation of the craft, or GUESTS if they are not so involved.

All persons on a boat are referred to as being ON BOARD; the term ABOARD is less correct.

Directions on Board a Boat

The BOW is sometimes the front end of a boat and sometimes the entire forward section without specific limits; the context in which the term is used will tell you which is meant. Similarly, the STERN is either the back end of the boat or its entire back section. The middle section of the boat, between the bow and stern sections, is called MIDSHIPS. PORT and STARBOARD (pronounced “starb’d”) are lateral terms. The port side of the boat is to your left and the starboard side is to your right when you’re on the vessel and facing the bow or, to express it differently, when you’re facing FORWARD. If you turn around to face the stern, you will be facing AFT, and the boat’s port side will now be to your right.

The bow is the forward part of the boat; the stern is the AFTER part. When one point is aft of another, it is said to be ABAFT it; when nearer the bow, it is FORWARD of the other. When an object lies on a line—or in a plane—parallel with the centerline of the vessel, it is referred to as lying FORE-AND-AFT, as distinguished from ATHWARTSHIPS, which means at right angles to the centerline.

The term AMIDSHIPS has a double meaning. In one sense, it refers to an object or area midway between the boat’s sides. In another sense, it relates to something midway between the bow and the stern. INBOARD and OUTBOARD, as directional terms, draw a distinction between objects near or toward amidships (inboard) and those away from the centerline or beyond the sides of the craft (outboard).

Someone or something that is ABOVEDECK is not literally above but is rather on the deck as opposed to being BELOW or in the cabin. Any location over the heads of observers who are abovedeck is said to be ALOFT and must be in the rigging or sails if it’s on the boat.

ORIENTING YOURSELF ON BOARD

Life afloat is always oriented to the boat, and not to the people on board. The PORT side, for instance, is on your left when you’re facing forward and on your right when you’re facing aft, but it’s always the port side, and the other side (to your right when you’re facing forward) is always starboard.

Anything toward the bow is FORWARD, while anything toward the stern is AFT. A position aft of an object is ABAFT of it. (A landmark may be said to be “abaft the beam.”) Something is ABEAM when it lies off either side of the boat at right angles to the keel.

Any part of the vessel or its equipment that runs from side to side—such as seats or a swim platform—is said to lie ATHWARTSHIPS. Anything that runs along or parallel with the vessel’s centerline is said to lie FORE-AND-AFT.

Anything in the middle of the boat is AMID-SHIPS, whether it’s oriented fore-and-aft or athwartships. INBOARD is toward the center, OUTBOARD away from it. Someone is going BELOW when he or she moves from the deck to a lower cabin inside the hull. The reverse is going ABOVE (decks). The term ALOFT is used for climbing the rigging and masts.

These terms relate to the hull and directions on board a boat. Note that length overall (LOA) is figured similarly for sailboats. Refer to Chapter 8 for terms specific to sailboats.

Terms Relating to the Boat

The basic part of a boat is its HULL. There is normally a major central structural member called the KEEL; beyond this, however, the components will vary with the construction materials and techniques. Boats may be of the OPEN type or may be covered with a DECK. As boats get above the smallest sizes, they may have a SUPERSTRUCTURE above the main deck level, variously referred to as a DECKHOUSE or CABIN (the term “cabin” is also used for spaces below the level of the deck). Small, relatively open boats may have only a SHELTER CABIN, or CUDDY, forward.

A vessel floats because water exerts a buoyant force on it. This force exactly equals the weight of the water that is displaced by the hull. In order to float, the vessel must weigh no more than the water it displaces. If the boat should weigh more, the buoyant force would be inadequate, and it would sink.

Since salt water is heavier and more dense than fresh water, a hull will displace a smaller volume of salt water, and its DRAFT—the distance vertically from the water surface to the lowest point on the boat—is less. For sailboats and displacement powerboats, the lowest point is normally the bottom of the keel; on planing motorboats, however, it is usually the propeller blade tips.

As a boat settles into the water—imagine it being lowered in slings from a crane—it reaches a level of equilibrium where the weight of displaced water matches that of the boat. This level on the hull is the WATERLINE. Just above the waterline, a stripe of contrasting color is often painted on the hull; this is the BOOT-TOP. Below the waterline, ANTIFOULING PAINT is usually applied to the hull to reduce the accumulation of marine growth, such as barnacles.

Terms Relating to the Hull

SHEER is a term used to designate the curve or sweep of the deck of a vessel as viewed from the side. Sheer is normally gracefully upward, but in some designs it can be downward, resulting in REVERSE SHEER. The side skin of a boat between the waterline and deck is called the TOPSIDES; the structural element at the upper edge is the GUNWALE (pronounced “gun’l”). (Note that “gun-whale” is not the correct spelling.) If the sides are drawn in toward the centerline away from a perpendicular as they go upward, as they often do near the stern of a boat, they are said to have TUMBLEHOME. Forward, they are more likely to incline outward to make the bow more buoyant and to keep the deck drier by throwing spray aside; this is FLARE. When the topsides are carried substantially above the level of the deck, they are called BULWARKS, and at the top of the bulwarks is the RAIL. More common than bulwarks are TOE RAILS, narrow strips placed on top of the gunwale to finish it off and provide some safety for persons on deck. LIFELINES are used on larger craft at the edges of the side decks to prevent people from falling overboard. These lines usually consist of wire rope, often plastic-covered, supported above the deck on STANCHIONS. If made of solid material—wood or metal—they are called LIFERAILS. Boats may also have waisthigh BOW RAILS of rigid tubing for the same safety purpose. A PULPIT is a forward extension, usually a heavy structure with rails extending up from it; see Figure 1-08. Bow rail installations on sailboats are also often called pulpits, whether they extend forward of the hull or not. Many sailboats also have stern pulpits, and these are sometimes called PUSHPITS.

Figure 1-08 A rail all the way at the bow is called a bow rail or pulpit. It is an important safety feature on sailboats, and often appears on powerboats as well. It should have adequate strength and be solidly mounted.

Along the sides of the hull there will be protrusions, either molded in or added externally, to protect the topsides from the roughness of piles and pier faces. These RUB RAILS or GUARDS are usually faced with metal strips for their own better protection.

Many hulls are fitted with a SPRAY RAIL external to the topsides just above the waterline. Such a rail usually extends about halfway aft from the leading edge of the hull, or STEM, and deflects downward any spray from the bow wave.

Hull Shapes

The lowest portion of the hull below the waterline is termed its BOTTOM. This may have one of three basic cross-sectional shapes—FLAT, ROUND, or V—or it may be a combination of two shapes, one forward gradually changing to the other toward the stern. There are also more complex shapes such as CATHEDRAL HULL, DEEP -V, MULTI-STEP, and others; see Figure 1-12.

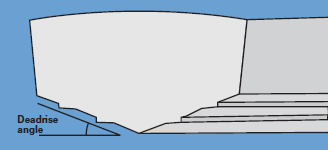

Figure 1-10 Hulls with deadrise angles at the transom of 16° to 19° are considered to be modified-V types. Steeper angles, some as high as 24°, are designated as deep-V hulls.

Bows & Sterns

The STEM is the extreme leading edge of a hull; on wooden craft it is the major structural member at the bow. The stem of a boat is PLUMB if it is perpendicular to the waterline, or RAKED if inclined at an angle. The term OVERHANG describes the projection of the upper part of the bow, or stern, beyond a perpendicular up from the point where the stem or stern intersects the waterline. EYEBOLTS or RINGBOLTS—to which all kinds of lines, ropes, and blocks may be attached—are frequently fitted through the stems of boats.

The flat area across a stern is called the TRANSOM. If, however, the stern is pointed, resembling a conventional bow, there is no transom and the boat is called a DOUBLE-ENDER; it can also be said to have a CANOE STERN. The QUARTER of a boat is the after portion of its sides, particularly the furthermost aft portion where the topsides meet the transom.

Additional Hull-Shape Terms

The lower outer part of the hull where the sides meet the bottom is called the TURN OF THE BILGE. If the boat is FLAT or V-BOTTOMED, the bottom and the sides of the boat meet at a well-defined angle rather than a gradual curve—this is the CHINE of the boat; see Figure 1-09. The more abrupt the angle of intersection of these planes, the HARDER the chine. SOFT-CHINE craft have a lesser angle; this term is sometimes applied to round-bottom boats, but this is not correct. Some modern boats are designed with MULTIPLE CHINES (LONGITUDINAL STEPS) for a softer ride at high speeds in rough water; this is a common feature of DEEP -V design.

Figure 1-09 A chine—the sharp angle at which the sides of a boat’s hull meet the bottom—provides this deep-V powerboat with better control and a dry ride at planing speeds. One of a pair of trim tabs is also seen in this photo (arrow).

Larger round-bottom vessels may be built with BILGE KEELS—secondary external keels at the turn of the bilge, actually fins—which reduce the vessel’s tendency to roll in beam seas.

The significance of the term DEADRISE can be appreciated by visualizing a cross-section of a hull; see Figure 1-10. If the bottom were flat, extending horizontally from the keel, there would be no deadrise. In a V-bottom boat, where the bottom rises at an angle to a horizontal line outward from the keel, the amount of such rise is the deadrise, usually expressed as an angle, but sometimes as inches per foot. The deadrise of a V-bottom boat is often constant from transom to midships but gets steeper forward for a smoother ride through waves.

With normal sheer, the deck of a boat, as viewed from the side, slopes up toward the bow, and the stern is at least level with amidships. FLAM is that part of the concave flare of the topside just below the deck. If it curves outward sharply, it will both increase deck width and reduce the amount of bow spray that blows aboard. The CUTWATER is the forward edge of the stem, particularly near the waterline. STEM BANDS of metal are frequently fitted over the stem for protection from debris in the water, ice, pier edges, etc. The FOREFOOT of a boat is the point where the stem joins the keel.

If the boat has an overhanging stern, this part of the hull is the COUNTER. Her lines aft to the stern are her RUN; lines forward to the stem are her ENTRANCE (or ENTRY). The descriptions FINE and CLEAN are often applied to the entrance and run. The term BLUFF is applied to bows that are broader and blunter than normal.

Figure 1-12 A flat-bottomed boat is inexpensive to build, but pounds. A round bottom provides a soft ride at displacement speeds but is unsuitable for planing. The deep-V hull is used on high-speed craft; cathedral hulls have good stability.

Terms Relating to the Keel & Rudder

The keel is the major longitudinal member of the hull. The RUDDER of a vessel is the flat blade at or near the stern that is pivoted about a vertical or near-vertical axis so as to turn to either side and thus change the direction of movement of the vessel through the water. A boat’s rudder is said to be BALANCED when a portion of its blade area extends forward of the axis of rotation; see Figure 1-11. Such a rudder is easier to turn. A metal fitting extending back from the underside of the keel for protection of the rudder and propeller is called a SKEG.

Figure 1-11 A balanced rudder has a portion of the rudder blade (red area) forward of the axis of the rudder shaft. This offsets much of the force required to turn the rudder to steer the boat.

The upward extension of the rudder through which force is applied to turn the rudder is the RUDDERPOST (or RUDDERSTOCK). A STUFFING BOX keeps the hull watertight where the rudderpost enters. (A stuffing box is also used where a PROPELLER SHAFT goes through the hull.) The rudder is linked to and turned by the vessel’s WHEEL; the connection may be by mechanical linkages, cables, or hydraulic lines. Some vessels may be steered by a TILLER—a horizontal arm or lever attached directly to the top of the rudderpost.

Displacement Hulls

A DISPLACEMENT HULL is one that achieves all of its buoyancy (flotation capability) by displacing a volume of water equal in weight to the boat and its load, whether underway or at rest. All cruising sailboats and large, low-speed powerboats (such as trawlers) take advantage of the low power demands of this type of hull; see Figure 1- 13. Little driving force is needed to move one of these boats until hull speed is reached. After this, no reasonable amount of increased power results in any efficient increase in speed. A close approximation of any vessel’s hull speed (in knots) can be found by multiplying the square root of its length at the waterline (LWL) in feet by the constant 1.3.

For example, a boat with a LWL of 36 feet has a theoretical hull speed of 7.8 knots: √36 x 1.3 = 6 x 1.3 = 7.8.

Figure 1-13 The force exerted by the wind on the sails creates a heeling effect as well as forward motion.

The need for an easily driven hull is obvious in a sailboat. In a powerboat, a displacement hull allows long-range cruising with a minimal expenditure of fuel. Cruising ranges in hundreds of nautical miles are not exceptional, especially for a trawler-type boat with a single diesel engine. Another advantage of a displacement hull is the ability to carry heavy loads with little penalty in overall performance.

Displacement hulls are normally round-bottomed. If one is flat-bottomed, it is usually for ease of construction rather than any reason of efficiency.

Planing Hulls

A PLANING HULL is one that achieves a major part of its underway-load-carrying ability by the dynamic action of its underside with the surface of the water over which it is rapidly traveling; at rest, a planing hull reverts to displacement buoyancy; see Figure 1-14. Planing action greatly reduces drag and wave-making resistance, allowing relatively higher speeds. Nearly all modern motorboats have planing hulls. Small, light sailboats with large sail plans (defined on page 29) can reach planing speeds in ideal conditions.

Figure 1-14 Hydrodynamic force lifts a planing hull partially out of the water, reducing drag and wave-making resistance. This makes high speed possible.

A planing hull is characterized by a flat aft run that meets the transom at a sharp angle. This angle allows the water flowing under the hull to “break away” cleanly from the transom. Hydrodynamic forces on the flat aft run lift the boat until only a small portion of its bottom is in the water. Distinct chines aid in speed and directional control as speed increases.

It takes considerable horsepower (hp) to achieve planing speeds, and that means greater fuel consumption. As a result, the cruising range of a planing hull is generally much less than that of a displacement boat carrying the same amount of fuel. Of course, the planing hull gets to its destination a lot sooner!

SAILBOAT HULLS

A sailboat needs a hull with a large amount of lateral resistance. Without this resistance it would blow sideways with the wind instead of sailing forward. Small, unballasted sailboats use movable appendages called CENTER-BOARDS, or DAGGERBOARDS, to provide lateral resistance. A centerboard is hinged and swings down out of a CENTERBOARD TRUNK, whereas a daggerboard is raised or lowered vertically and can be completely removed from the boat. Another method of obtaining lateral resistance, now seldom used, is through two LEEBOARDS, which look like centerboards, attached to the gunwales, one on either side.

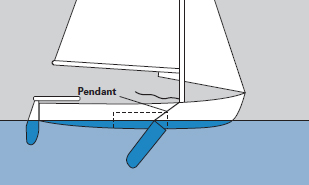

A centerboard is raised or lowered in its trunk by a pendant (also called “pennant”) to permit adjustment according to the point of sail or for shallow water.

Larger sailboats have permanently attached, fixed external keels designed to provide lateral resistance. Older designs have a FULL KEEL that starts near the bow and continues aft until it joins the rudder. In recent years, FIN KEELS and WINGED KEELS have become popular because they allow greater maneuverability and improved upwind performance. The rudder of a fin-keel boat may be attached to a small SKEG for protection, or it may be a freestanding appendage known as a SPADE RUDDER.

A full keel is usually found on older, larger boats. It may have internal ballast or exterior ballast bolted onto the hull—which also acts as a grounding shoe.

Both full and fin keels also serve as the craft’s fixed ballast. Modern practice is to form these keels out of lead or cast iron so the ballast is outside and below the hull where it will have the maximum countering effect on heeling. Ballast has no effect until the boat begins to heel. As the angle of heel increases, the ballast exerts an increasing force to right the boat. A ballasted sailboat will typically HEEL—tip sideways—rather easily at first, and then become “stiffer” as the ballast takes effect. Each sailboat has an angle of heel where the hull achieves maximum performance.

V Hulls

POUNDING—coming down hard on successive waves—inevitably occurs when any boat is driven through rough water at high speeds. It is accentuated by the broad, flat sections required of an efficient planing hull. Slowing down eliminates the problem, but many planing hulls become much more difficult to maneuver at slow speeds. The need to compromise between planing speeds and sea-keeping qualities has led to the almost universal acceptance of the V hull, a design developed in the 1960s. A steep deadrise provides acceptable wave riding along with sufficient planing ability to achieve high speed. Whether modified-V or deep-V aft of amidships, a V hull’s sections will have steeper deadrise forward to reduce pounding.

TRIM TABS are rectangular control flaps that project approximately parallel to the water’s surface at the lower edge of the transom; refer to Figure 1-09. Deep-V and modified-V hulls are very sensitive to trim tab adjustment. Adjusting the tabs down pushes the stern up and the bow down, which helps the hull rise to planing trim. These hulls are also sensitive to small changes in the angle of propeller thrust with an outboard motor or inboard/outboard drive.

Semi-planing Hulls

A SEMI-PLANING (or SEMI-DISPLACEMENT) hull is one that gets a significant portion of its weight-carrying capability from dynamic action, but which does not travel at a fast enough speed for full planing status. It is often a hull that is round-bottomed forward, gradually flattening out toward the stern to provide a planing surface.

Ballasted Hulls

Whereas LISTING is tipping caused by improper weight distribution, HEELING is the sideways tipping of a boat caused by wind in the sails. A sailboat must be able to resist this force, which acts high above the deck where it has maximum impact on stability. The boat can fight the heeling force with hull shape and BALLAST (weight put on board specifically for this function). Considering STABILITY, a flat-bottom hull presents immediate and strong resistance to heeling—meaning that it has great INITIAL STABILITY—but will ultimately give up with a sudden capsize, turning bottom up. At the other extreme, a round hull required for efficient sailing offers little initial resistance to heeling but when well designed and ballasted possesses ample ULTIMATE STABILITY, or resistance to capsize. A fine hull (see page 34) offers less resistance to heeling than a beamy one (see page 26).

On smaller sailboats, the crew can act as “live ballast,” shifting to the windward side to counteract heeling. Some larger sailing craft have BALLAST TANKS on each side of the hull, and water ballast can be pumped from one side to the other to counteract heeling.

Deck Terms

A deck is an important horizontal structural part of a boat, its design dictated as much for strength as by aesthetics. If a deck is arched to aid in draining off water, it is said to be CAMBERED. Similarly, camber occurs on the tops of cabins, deckhouses, etc. The deck over the forward part of a vessel, or the forward part of the total deck area, is termed a FOREDECK. Similarly, the AFTDECK (afterdeck) is located in the after part of the vessel. SIDE DECKS are exterior walkways from the foredeck aft. Safety demands that all walking areas of exterior decks be treated with nonskid material.

HATCHES (sometimes called HATCHWAYS) are openings in the deck of a vessel to provide access below. COMPANION LADDERS (steps) lead downward from the deck; these also are termed COMPANIONWAYS.

COCKPITS are open wells in the deck of a boat outside of deckhouses and cabins. The deck of a cockpit, or of an interior cabin, is often called the SOLE. COAMINGS are vertical pieces around the edges of the cockpit, hatches, etc., to prevent water on deck from running below.

Interior Terms

Vertical partitions, corresponding to walls in a house, are called BULKHEADS. WATERTIGHT BULKHEADS are solid or are equipped with doors that can be secured so tightly as to be leakproof. The interior areas divided off by bulkheads are termed COMPARTMENTS—such as an engine compartment—or cabins—such as the main cabin or aft cabin. Some areas are named by their use; the kitchen aboard a boat is its GALLEY; see Figures 1-15 and 1-16. The toilet area is the HEAD; the same name is also given to the toilet itself, which will be attached to some sort of MARINE SANITATION DEVICE (MSD;). The OVERHEAD is the nautical term for what would be the ceiling of a room in a house; if made of soft material, it can be called the HEADLINER. CEILING, on a boat, is light planking or plywood sheeting on the inside of the frames, along the sides of the boat. FLOORS, nautically speaking, are not laid to be walked upon, as in a house, but are structural parts adjacent to the keel.

Figure 1-15 On board sailboats (above) and powerboats, the galley is frequently part of the main cabin. There is often an adjacent dinette, the table of which can be lowered to make an additional sleeping berth.

The term BILGE is also applied to the lower interior areas of the hull of a vessel. Here water that leaks or washes in, or is blown on board as spray, collects as BILGE WATER, to be later pumped overboard by a BILGE PUMP.

BERTHS and BUNKS are seagoing names for beds aboard a boat. Closets are termed LOCKERS; a HANGING LOCKER is one tall enough for full-length garments; a WET LOCKER is one specifically designated for soggy FOUL-WEATHER GEAR (rain jackets and pants). Chests and boxes may also be called lockers. A ROPE or CHAIN LOCKER is often found in the bow of a boat for stowing the anchor line or chain; this area is called the FOREPEAK. LAZARETTES are compartments in the stern of a vessel used for general storage.

Figure 1-16 This view shows the interior arrangements of a midsize power cruiser with comfortable accommodations for four persons, expandable when needed for two to four more. On this boat, the main saloon is raised above the engines, and the galley is “down.”

When something is put away in its proper place on a vessel, it is STOWED. The opposite of stowing, to BREAK OUT, is to take a needed article from its locker or other secure place.

HELM is a term relating to the steering mechanism of a craft. An individual is AT THE HELM when that person is at the controls of the boat; he is then the HELMSMAN (male or female). The BRIDGE of a vessel is the location from which it is steered and its speed controlled. On small craft, the term CONTROL STATION is perhaps more appropriate. Many motorboats have a FLYING BRIDGE, an added set of controls above the level of the normal control station for better visibility and more fresh air. These, also called FLYBRIDGES, are sometimes open, but often have a fixed or a collapsible (“Bimini”) top for shade, and perhaps clear plastic CURTAINS forward, aft, and around the sides for protection from the weather; see Figure 1-17. Medium-size and larger boats, particularly sailboats, may have a specially designated area in a cabin below for a NAV STATION equipped with a CHART TABLE.

Figure 1-17 A power cruiser’s flying bridge, usually called a flybridge, is an upper steering position originally intended as a platform to spot game fish.

Portholes & Portlights

On a boat, a PORT (or PORTHOLE) is an opening in the hull to admit light and air. The glass used in it to keep the hull weathertight is termed a PORTLIGHT if it can be opened, and a DEADLIGHT if it cannot. Openings in cabins above the deck are generally WINDOWS that open by sliding to one side.

The Dimensions of a Vessel

The length of a boat is often given in two forms: LENGTH OVERALL (LOA) and LENGTH AT THE WATERLINE (LWL), also known as the LOAD WATERLINE; see page 18. LOA is measured from the forward part of the stem to the after part of the stern along the centerline, excluding any projections that are not part of the hull, such as a BOWSPRIT or SWIM PLATFORM. A boat with a LOA of 35 feet (10.7 m) might have a total length of 42 feet (12.8 m) when these appendages are taken into consideration. In some powerboats, the swim platform is an integral part of the hull and thus included in any LOA measurements. The waterline of a boat is the plane where the surface of the water touches the hull when it is loaded normally; LWL is measured from stem to stern in a straight line along this plane. The greatest width of a vessel is its BEAM; boats of greater than normal beam are described as BEAMY. A vessel’s DRAFT is the depth of water required to float it; it is said to “draw” that depth. Draft should not be confused with the term DEPTH, which is used in connection with large vessels and documented boats and is measured inside the hull from the underside of the deck to the top of the keel. The height of a boat’s topsides from the waterline to the deck is called its FREEBOARD; this is normally greater at the bow than at the stern. HEADROOM is the vertical distance between the deck and the cabin or canopy top, or any overhead structure.

Powerboat Types

Powerboat builders use numerous terms to distinguish boat types, and they are not always consistent. However, a few basic terms seem to be universal, surviving changes in style. A RUNABOUT usually seats four to six persons. BOWRIDERS have additional seating in the open bow accessed via a walk-through windshield. Neither of these types has formal sleeping accommodations, though seats may fold down for sunning or napping.

On runabouts of about 20 feet (6.1 m) or longer, the space at the bow becomes large enough for a small enclosure or cabin, termed a CUDDY (the oft-heard “cuddy cabin” is redundant). While not luxurious, the cuddy does offer shelter in wet weather and may also enclose a portable head.

Powerboat Cockpits & Bridges

The central element of a small powerboat is the CONTROL CONSOLE. Controls such as the STEERING WHEEL and the THROTTLE and SHIFT LEVERS should be placed within easy reach. There should be good sight lines so that engine instruments and electronic displays are readily viewable. As boat length increases, it becomes both possible and advisable to elevate the helm station for better visibility and give it the traditional name, “bridge.”

Limited space makes it a challenge to install all of the radio communication and navigational electronic equipment on the console in a practical fashion. One common and sometimes overlooked problem is that of placing the COMPASS in a position from which it can be easily read and is as free as possible from undesired magnetic influences.

At about 30 feet (9.1 m) of overall length, it becomes possible to provide a flybridge. This location for the controls has become popular as it provides better visibility all around the horizon. Sun and weather protection is usually provided by a Bimini top, frequently with all-around curtains.

Many motorboats have dual steering stations, one in the cabin below and one on the flybridge. Steering and engine controls are duplicated, as are some of the electronics. This design allows for a comfortable operating position in any weather.

Figure 1-21 A swim platform allows easier entry into and exit from the water or a dinghy; it can also be very helpful in a man-overboard situation. Be sure the engine is shut off when people are in the water near the boat. This platform is not integral with the hull and should not be included when measuring the boat’s overall length.

Powerboats often have swim platforms just aft of the transom that also serve as boarding platforms for dinghies; see Figure 1-21. Some sport-fishing craft will have gates in the transom, and no swim platform, to help in boarding large game fish.

Center-consoles & Daycruisers

A CENTER-CONSOLE boat has its helm and engine controls located on the centerline approximately midway between the bow and stern; see Figure 1-18. These craft are popular with anglers as they have the maximum deck space for a boat’s overall length (LOA). Seating is usually limited to a pair of swivel or bench seats, sometimes with additional seating in the stern. Fishing enthusiasts can handle rods or swing nets around the boat’s entire perimeter. The lack of enclosed space makes this type undesirable for cruising. Center-consoles range in length from less than 15 feet (4.6 m) to 35 feet (10.7 m) or longer.

Figure 1-18 The 30-foot outboard-powered center-console at left is designed as a fishing machine, with open room for anglers to maneuver everywhere in the boat. The 29-foot walk-around at right has a cabin for accommodations and storage, while narrow side decks allow access to the foredeck for fishing.

In the range of 20 feet to 25 feet (6.1 to 7.6 m), DAYCRUISERS are large enough to have a small cabin forward with seated headroom. This will probably have a V-BERTH, a portable head, and a small galley consisting of a tabletop stove and a basin, with a folding table.

Express & Sedan Cruisers

Longer than about 25 feet (7.6 m), powerboat styles begin to diverge. Differences in accommodation layout are reflected in differences in their hull and superstructure shapes. EXPRESS CRUISERS form one branch of powerboat design, whereas another is composed of SEDAN CRUISERS, sometimes called CONVERTIBLES; see Figure 1-19.

Figure 1-19 The express cruiser is a modern, sporty design that enlarges the sportboat configuration to include accommodations in the forward cabin and an open raised bridge. It has a planing hull.

An express cruiser takes the basic sportboat or runabout configuration and enlarges it to a length of 40 feet (12.2 m) or more. The craft’s FOREDECK is long and unobstructed, interrupted only by hatches that provide ventilation to the enclosed space below. The control station, or bridge, is set well aft and often slightly higher than the level of the open cockpit near the stern. A RADAR ARCH is sometimes included to provide high and clear mounting space for radar and other antennas. An express cruiser is typically quite stylish and high-powered.

A sedan or convertible cruiser puts the main interior space on the same level as the cockpit. The interior is divided into two parts: a main cabin or SALOON at the level of the cockpit and a forward cabin lower and under the foredeck. (“Saloon” is the proper nautical word, although “salon” will be seen in some advertising literature.) Smaller sedans usually will have their galleys within the main cabin; this is known as a GALLEY UP layout. The GALLEY DOWN layout has the galley between the saloon and the forward cabin, at the level of the latter.

Aft-cabin Cruisers

As length increases, it becomes possible to have sleeping quarters below the level of the deck at the stern in an AFT CABIN. The engines are moved forward to the middle area of the hull beneath the main cabin, and the resulting design is called a DOUBLE-CABIN cruiser. (If the boat is large enough, there may be a second sleeping cabin aft, and the design becomes a TRI-CABIN or TRIPLE-CABIN cruiser.)

Sport Fishermen

A sport-fishing boat can be a convertible or sedan that is rigged for fishing, or it can be a true SPORT FISHERMAN (sometimes colloquially called a “ SPORTFISH ”) with a longer foredeck, shortened main cabin, and much larger cockpit aft. Purpose-designed game-fishing craft usually have a TUNA TOWER with a set of controls at a maximum height for better fish spotting; some have a control station in the cockpit for boat handling during the final fighting and boarding of game fish. The boat will have OUTRIGGERS for additional trolling lines and the cockpit will be outfitted with special FIGHTING CHAIRS.

Recreational Trawlers

Within the commercial fishing community, the word “trawler” has a specific meaning relating to a style of fishing, but in recreational boating the term is used much more loosely. In general, a cruiser that does not have sufficient horsepower to get into a planing mode is known as a TRAWLER.

The trawler’s displacement hull is designed to ride through and not over the water; see Figure 1-20. It can vary from one with soft bilges to one with hard chines. Nearly all trawlers have a significant external keel. Speed is normally limited to hull speed; the engine can be either single or twins. These craft have very modest fuel consumption characteristics and are popular for traveling at speeds of 7 to 10 knots over long distances. Some trawler-style cruisers are equipped with semi-planing hulls and high-horsepower diesel engines that offer improved fuel efficiency at displacement speeds and shorter transit times at higher speeds.

Figure 1-20 A trawler was originally designed as a low-speed, seaworthy commercial fishing vessel. As a recreational boat, trawlers are fuel-efficient and offer many on-board living advantages.

Sailboat Types

Sailboats are seldom identified as to their cabin layouts as are powerboats, probably because less variety is possible. Instead, sailing craft are usually known by their SAIL PLANS: the number of masts and the position of their sails. Smaller sailboats almost always have a cockpit at or near the stern. Interior accommodations are forward in one or more cabins. While interior space receives the most attention from new boat buyers, it is actually the cockpit where most sailors’ time is spent; see Figure 1-22.

Many larger sailboats are of the CENTER-COCKPIT style, in contrast with the aft-cockpit layout shown in Figure 1-22. With sufficient beam at the stern and the cockpit more nearly amidships, it becomes possible to have an adequate aft cabin behind or partially under the cockpit. To retain useful space below, however, it is necessary to raise the cockpit sole to the level of the deck, and the result is ungainly in center-cockpit boats of less than about 40 feet (12.2 m) in length.

As sailcloth, rigging wire, and metal masts have improved in strength, taller masts have become possible without increasing weight. Greater height allows more sail area or the same area in a more efficient shape. Reduction in rigging weight, more stable hulls, and better deck equipment have made possible simpler sail plans.

Figure 1-22 Interior layouts for sailboats vary widely depending on the length and beam of the craft. This midsize cruising sailboat offers accommodations for several crew and guests.

Figure 1-23 When the wind blows too strongly for safety or comfort, it is time to reduce the sail area by reefing the mainsail and/or genoa or switching to a smaller headsail as described in Chapter 8.

Sailing Rigs

RIG is the general term applied to the arrangement of a vessel’s masts and sails. Most recreational sailing craft are now fitted with triangular-shaped sails and are said to be MARCONI-RIGGED (or JIB-HEADED). If a four-sided sail with a gaff is used, the boat is described as GAFF-RIGGED.

The principal sail of a boat is its MAINSAIL. A sail forward of the mast—or ahead of the most forward mast if there is more than one—is a HEADSAIL; a single headsail is usually termed a JIB.

If a boat has no headsails, it is a CATBOAT; she may be either Marconi-rigged or gaff-rigged. A boat having a single mast, with a mainsail and a jib, is a SLOOP. On some boats additional headsails are set from a BOWSPRIT, a spar projecting forward over the bow (see Chapter 8 for more information on masts and spars).

A modern CUTTER is a variation of the sloop rig in which the mast is stepped further aft, resulting in a larger area for headsails. A cutter normally sets two headsails—a FORESTAYSAIL with a jib ahead of it.

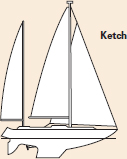

YAWLS have two masts, the after one of which is much smaller and is stepped abaft the rudderpost. A KETCH likewise has two masts with the after one smaller, but here the difference in height is not so marked and the after mast is stepped forward of the rudderpost. The taller mast is the MAINMAST; the shorter mast of either rig is the MIZZENMAST, and the after sail is the MIZZEN.

SCHOONERS have two or more masts, but unlike yawls and ketches the after mast of a two-masted schooner is taller than the forward one (in some designs, the two masts may be the same height). Thus the after mast becomes the mainmast and the other the FOREMAST. Additional names are used if there are more than two masts.

SAIL PLANS FOR VARIOUS RIGS

The Sloop

The most popular plan is the SLOOP, which has one mast forward of amidships and two sails. The forward sail is the HEADSAIL or JIB, and the aft one is the MAIN-SAIL, also called the MAIN. A sail’s leading edge is its LUFF; its after edge is the LEECH and its bottom edge is the FOOT. The jib is attached to the HEADSTAY with HANKS, strong hooks with spring-loaded closures. An alternative design uses a semiflexible track, or FOIL, on the stay that accepts a BOLTROPE sewn along the sail’s luff. Such tracks offer better air-flow over the luff, making the sail more efficient; this also allows ROLLER FURLING to reduce sail area in heavy weather. Some mainsails may be roller-furled into a slot in the mast or boom, making them easier to REEF; refer also to Figure 1-23 and Chapter 8.

Headsails can have many names, depending on their size, weight, and shape. A STORM JIB is a small sail made of heavy cloth to be flown in heavy weather; a WORKINGJIB is flown in a moderate to fresh breeze; and a GENOA, an oversize jib reaching well past the mast and built from lighter sailcloth, provides greater power when the wind is light. Genoas come in a range of sizes, the larger of which may have a surface area greater than the mainsail. As roller-furling mechanisms have become more reliable and versatile, a single roller-furling headsail—the size of a large genoa when fully set and the size of a working jib when partially furled—is an increasingly popular substitute for a range of headsails that must be raised and lowered as the wind strengthens or lightens. This approach trades a slight loss of aerodynamic efficiency for a large increase in convenience.

When a sloop’s jib is hoisted from a stay running to the top of the mast, it is a MASTHEAD SLOOP. If the jib is hoisted to a lower point, the sloop has a FRACTIONAL RIG. The headsail of this type of rig only reaches to a fraction of the height of the mast—typically three-quarters or seven-eighths.

The foot of a working jib may be attached to a small spar called a CLUB. This arrangement allows the sail to be SELF-TENDING because it can be controlled by one SHEET rather than two. A CLUB-FOOTED JIB can be TACKED (see Chapter 8) without releasing one sheet and hauling in on the other. Self-tending jibs are easier to handle but limited to working-jib size. Genoas, which overlap the mainmast, cannot be controlled with a club and single sheet.

The Cutter

A single-masted sailboat similar to the sloop, the CUTTER has its mast more nearly amidships, leaving room for a larger FORE-TRIANGLE filled by two headsails. The outer headsail is the jib, while the inner is a STAYSAIL. A cutter rig has two advantages. First, it divides sail area among smaller sails that are more easily handled. Second, it provides more sail reduction options in rough going than does a sloop. And when the jib is lowered, the remaining staysail is smaller and closer to the mast, giving added safety in a seaway. This rig has been a longtime favorite among cruising sailors. A modern DOUBLE HEADSAIL SLOOP—essentially a cutter with its mast slightly farther forward—accomplishes much the same thing.

The Ketch & Yawl

The KETCH and YAWL look somewhat alike. Both have a tall MAINMAST and a shorter MIZZENMAST (a smaller mast aft of the mainmast) that flies a MIZZEN sail. The distinction between a ketch and a yawl is a common topic of debate among sailors. Traditionally, the governing rule is location of the mizzenmast: If it is ahead of the rudderpost, the boat is a ketch; however, if it is behind the rudderpost, the boat is a yawl.

Ketches and yawls are DIVIDED RIGS, meaning the sail area is divided between two masts. Either craft may have a masthead or a fractional rig forward of the mainmast with one or more headsails. Individual sails are more manageable in size and more easily handled by a small crew. Both may fly a large jib-like sail between the masts called a MIZZEN STAYSAIL. Because of the extra rigging and mast surface area exposed to the wind, these rigs have more WINDAGE and are less effective on smaller boats where windage is relatively more important. Ketch rigs—which are more versatile than yawls by virtue of their larger and more powerful mizzens—are popular among cruising sailors for long-distance voyages. Mizzenmasts are a practical location for mounting electronic antennas.

The Schooner

A SCHOONER is a vessel with at least two masts (in the 19th century, some carried up to seven). On two-masted schooners, the mainmast is aft, and is at least as tall or taller than the forward mast, or FOREMAST. Most schooners used multiple headsail combinations including—from top down—the flying jib, the jib, and the FORESTAY-SAIL. The number of headsails and their names vary with the location and the time period.

Schooners were workboats, mainly fishing vessels. Equipped with tall, powerful rigs, they raced home from the Grand Banks (southeast of Newfoundland) to get top dollar for their catches.

Early schooners were GAFF RIGGED with FOUR-SIDED (four-edged) sails on the mainmast and foremast supported by a spar—the GAFF—at their top edges. Often, a triangular TOPSAIL was flown above both the main and foresails. For extra power, a sail called a FISHERMAN was set between the masts. These complex rigs required more deck hands than are standard today. The modern schooner rig may carry a MARCONI or JIB-HEADED main and foresail (triangular as in the mainsail on a sloop). The foresail may be LOOSE-FOOTED, not fitted with a boom, and there may be only one headsail.

Schooners are most comfortable in steady trade winds on long ocean passages. Although they do not sail to windward as well as other rigs, they make up for it when the wind is on or aft of the beam.

The Catboat

A boat that caries only one mast set well forward and no headsails is known as a CATBOAT. When fishing was done under sail, catboats were practical for coastal fishermen because there was less rigging to get in the way when handling nets or unloading the catch. Also, the boat’s single sail was easier for one person to handle.

Recent cat-rigged designs make use of UNSTAYED masts (masts that have no standing rigging, being supported only by the deck). With less windage, and high, narrow sail plans, these can often perform nearly as well as sloop rigs. Today you can see unstayed cat ketches and the occasional cat schooner.

Square-Rigged Vessels

Vessels on which the principal sails are set generally athwartships are referred to as SQUARE-RIGGED. These four-sided (four edged) sails are hung from horizontal spars known as YARDS. Headsails are carried, as on other rigs, forward of the foremost mast. STAYSAILS may also be set between the masts, and the aftermost mast of a square-rigged vessel normally carries a fore-and-aft sail. Very limited use is made of this rig for recreational sailing vessels.

Sailboat Cockpits

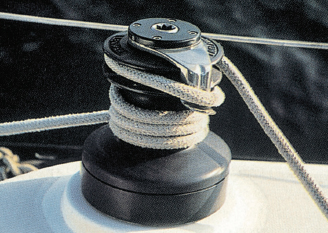

Because the cockpit of a cruising sailboat serves as both social gathering place and a control center, compromises must be made between access to HALYARDS and SHEETS (lines to hoist and trim sails) or to WINCHES (devices to increase the pull on such lines) and the comfort of those on board; see Figure 1-24. Typical cockpits have facing bench seats on each side that are close enough together that individuals can brace themselves as the boat heels. Cockpit seats often lift open to reveal SEAT LOCKERS—stowage for SAIL BAGS, an uninflated life raft, dock lines, sheets, winch handles, and the accumulated etceteras of life afloat.

Figure 1-24 A winch revolves clockwise only, resisting the strain of sheets and providing extra power for trimming sails. Self-tailing winches, as shown above, allow one person to do the work of two.

A PEDESTAL with steering wheel may stand near the aft end of the cockpit. On top of this may be a BINNACLE, a case that houses a compass (refer to Chapter 13). The pedestal may also support shift and throttle levers for an auxiliary engine. On smaller sailboats, there may be no pedestal, with steering being accomplished using a tiller.

Connecting the sailboat cockpit to the main cabin below is a companionway consisting of a steep set of ladder-like steps, a GRAB RAIL, and a SLIDING HATCH. The part of the cockpit that must be stepped over at the top of the companionway is called a BRIDGE DECK, an important safety feature. If the cockpit were to fill with water from a large wave, this barrier would prevent it from going down into the interior and collecting in the bilge. Daysailers and inshore cruising sailboats don’t need bridge decks, but a seagoing sailboat should have one.

Water in the cockpit drains through at least two SCUPPERS (drain holes) leading from the lowest points on the cockpit sole through the hull. The cockpit sole must be above the waterline at any angle of heel for these drains to work.

Aft of the cockpit there is often a lazarette, accessed through a hatch. In some more recent designs, there may be a set of steps leading down to a swim platform just above the water. This platform, in addition to being used for getting into and out of the water for swimming, is useful for boarding or disembarking from a dinghy; it can also be helpful in retrieving a person from the water in a man-overboard (MOB) situation.

Construction Terms

The term FASTENING is applied to various screws, bolts, or specially designed nails that hold equipment and other gear to the hull or superstructure. THROUGH FASTENINGS are bolts that go all the way through the hull or other base timbers, secured with a washer and nut on the inside; a BACKING BLOCK is generally advisable for spreading the stress and to gain additional strength. BEDDING COMPOUND, a sealer and adhesive, should be used between any fitting and the surface on which it is mounted.

SEA COCKS are valves installed just inside THROUGH-HULL FITTINGS where water is taken in or discharged for engine cooling, operation of heads, etc. Sea cocks are important safety devices as they can shut off the flow of water if a hose breaks or a piece of equipment must be worked on.

Areas that are varnished to a high gloss are termed BRIGHTWORK. (In naval usage, this term may be applied to polished brass.) A TACK RAG is a slightly sticky cloth that is wiped over surfaces that are to be varnished or painted just before the brush is applied, to remove all dust and grit.

When the rudder of a boat is exactly centered, one spoke of the steering wheel should be vertical; this is the KING SPOKE and is usually marked with special carving or wrapping so that it can be recognized by feel alone. (The wheel of a hydraulic steering system may not have an unvarying center position.) Some craft will have on the instrument panel an electrical RUDDER ANGLE INDICATOR.

Many motorboats are constructed with a small SIGNAL MAST from which flags can be flown. These flags are hoisted on SIGNAL HALYARDS. When partially hoisted on any mast, flags are said to be AT THE DIP; when fully hoisted, they are termed TWO-BLOCKED.

Vessels, including boats, are normally designed by a NAVAL ARCHITECT. In doing so, he or she prepares detailed PLANS and SPECIFICATIONS, including the LINES (shape) of her hull. CLEAN is a term applied not to a boat’s condition, but rather to her lines. If the lines are FINE, so that she slips easily through the water, the lines are said to be clean.

A MARINE SURVEYOR is a highly experienced person whose job it is to make detailed inspections (SURVEYS) of boats and ships to determine the condition of hull, equipment, machinery, etc.; see Figure 1-25.

Figure 1-25 Generally, a survey is conducted when the boat is out of the water. A marine surveyor gives the person who has commissioned the survey an extensive report on all structural elements of the boat, including suggestions regarding needed repairs.

Fiberglass Construction

There are some recreational boats still in use that are of wood construction, and a few are still built each year. While there are dedicated wooden-boat enthusiasts and popular publications targeted for them, the majority of recreational boats are made of FIBERGLASS. The full name of this material is “fiber-reinforced plastic,” which properly describes the material as glass fibers embedded in a thermosetting plastic, usually POLYESTER or VINYLESTER but sometimes EPOXY (stronger, but more expensive). In recent years glass has sometimes been replaced with fibers made of carbon or synthetics such as Kevlar for greater strength. Large yachts are often made of aluminum or with steel hulls and aluminum superstructures.

There are many advantages to fiberglass construction; see Figure 1-26. Surfaces can be of any desired compound curvature; multiple identical hulls, superstructures, and lesser components can be made economically from reusable molds; and plastic hulls completely resist attack by marine organisms, although they do require antifouling paint if kept in salt water for long periods.

Figure 1-26 Fiberglass construction allows multiple hulls, superstructures, and other components to be made economically from reusable molds. Surfaces can be of any desired compound curvature.

Fiberglass construction uses a female mold into which multiple layers are placed. Each layer is LAID UP in turn following a MOLD SCHEDULE, or list of layers. Typically, this might consist of a GEL COAT (the outer skin of the hull), followed by a layer of mat or chopped strands of fiberglass to ensure that the weave of subsequent layers of roving material does not show through the gel coat. The layers of roving (a coarse, heavy weave) might be followed by core material (see below) and further interior layers. A special layer, called an OSMOSIS BARRIER, is usually placed just under the gel coat to prevent the movement of water through the gel coat that could eventually cause BLISTERS. More modern, sophisticated and expensive building methods include VACUUM BAGGING, where layers of fiberglass and other composites are impregnated with resin and enclosed in an airtight plastic bag. A powerful vacuum then compresses the entire laminate, minimizing structural voids and ensuring a high fiber-to-resin ratio for a lighter, stronger vessel.

Molded construction is also used for one-off, high-performance racing boats—both power and sail. While the methods used are similar to production boats, these often make use of better (more expensive) materials, such as UNI-DIRECTIONAL, BIAXIAL, or even more specialized glass cloths. Epoxy resins frequently replace the polyesters used in more conventional boats, and Kevlar, CARBON FIBER, and other strong, light, expensive reinforcing materials may replace ordinary fiberglass in critical areas or throughout the boat.

Secondary parts of the boat are laid-up in their own molds, usually with a simpler schedule than is used for the hull. These parts are removed from their molds, fitted with various hardware and other components (cleats, hatches, rails tanks, electrical wiring harnesses, etc.), then assembled to complete the craft.

Fiberglass is strong but heavy, and not very stiff. Sufficient stiffness can be achieved without undesired weight, by using CORED CONSTRUCTION, also called COMPOSITE CONSTRUCTION. Two layers of fiberglass are separated by a light but compression-resistant core, typically a rigid foam or balsawood. Stiffening can also be achieved by the use of box-like sections, called HIGH-HAT SECTIONS, which form a grid or run longitudinally inside the hull or under a deck.

The principal engineering problem, once the molding is complete, is how best to attach the deck to the hull. Theories abound, but in general the best HULL-DECK JOINTS offer large surfaces for bedding compound or other sealers and adhesives; see Figure 1-27. Thick wood or metal backing plates for through-bolt attachments are also requirements. Finally, there must be provisions for rub rails and stanchion bases.

Figure 1-27 Hull-deck joints must be rigid and watertight. Most are molded box-sections that are liberally caulked with permanent adhesive sealants. Stainless steel through-bolts provide additional security. The hull-deck joint shown above is typical of a small powerboat.

Fiberglass is useful also in covering wood, either in new construction or in the repair of older boats, where its properties of ADHESION are important.

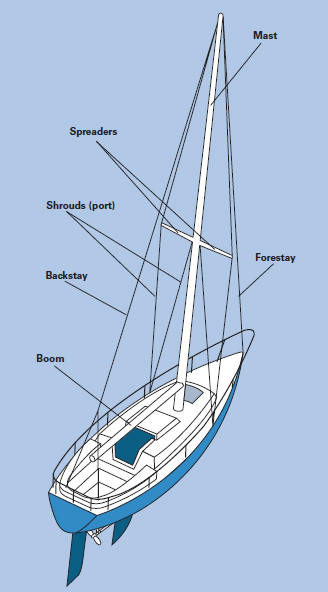

Sailboat Masts & Spars

While carbon fiber is also used in the construction of sophisticated racing sailboat masts, the majority of modern sailing craft have spars that are made of extruded aluminum alloy. Most masts and booms are simple tubes. Where more efficient shapes are required, they can be fabricated by cutting and rewelding basic extrusions.

Aluminum is strong, so mast failures are rare except on hard-pressed racing boats. Its main advantage is the material’s light weight, which keeps the boat’s center of gravity low and improves sailing performance.

Terms Relating to Equipment

CHOCKS are deck fittings, usually of metal, with inward curving arms through which mooring, anchor, or other lines are passed to lead them in the proper direction both on and off the boat; they should be very smooth to prevent excess wearing of the line. CLEATS are fittings of metal or wood with outward curving arms, called HORNS, on which lines can be fastened; see Figure 1-28.

Figure 1-28 Cleats, chocks, and bitts (seen above, clockwise from upper left) are used on both powerboats and sailboats. Their shape and size may vary with the size of the craft.

While cleats are generally satisfactory for most purposes on a boat, wooden or metal BITTS are recommended if heavy strains are to be made. These are stout vertical posts, either single or double. They may take the form of a fitting securely bolted (never screwed) to the deck, but even better—as in the case of a SAMSON POST—passing through the deck and STEPPED at the keel or otherwise strongly fastened. Sometimes a round metal pin, called a NORMAN PIN, is fitted horizontally through the head of a post or bitt to aid in BELAYING the line; see Figure 1-29.

Figure 1-29 A sampson post, a strong fitting on the foredeck, secures the anchor rode or dock lines. The norman pin, which passes through it, keeps the line from slipping up and off the post, and provides a means of securing the line with half hitches.

Where lines pass through a chock, or rub against a surface, they should be protected from wear by a CHAFE GUARD; see Figure 1-30.

Figure 1-30 Chafe guards should be used on any lines that pass over an abrasive surface. They may be a purchased item, as shown above, but can be homemade by using a split garden hose or special tape applied to the lining.

FENDERS are relatively soft objects of rubber or plastic used between boats and piles, pier sides, seawalls, etc., to protect the topsides from scarring and to cushion any shock of the boat striking a fixed object; see Figure 1-31. Fenders (sometimes referred to in a landlubberly fashion as “bumpers”) are also used between boats when they are tied, or RAFTED, together. FENDER BOARDS are short lengths of stout planking, often with cushion material or metal rubbing strips on one side. They are normally used horizontally with two fenders hung vertically behind them to provide a wider bearing surface against a single pile.

Figure 1-31 A fender is used to protect the side of a boat from damage by a rough pile or pier face. It also cushions any shocks to the boat from waves or the wake of passing vessels. Fenders can be hung horizontally or vertically as required by the surface they bear upon.

LIFE PRESERVERS—also called PERSONAL FLOTATION DEVICES, abbreviated PFD—provide additional buoyancy to keep people afloat when in the water. They take the form of cushions, belts, vests, jackets, inflatables, and ring buoys. PFDs must be of a USCG –approved type to meet the legal requirements as set forth in Chapter 3.

A BOAT HOOK is a short shaft of wood or metal with a hook fitting at one end shaped to aid in extending one’s effective reach from the side of the boat, such as when putting a line over a pile or picking up an object dropped overboard. It can also be used for pushing or FENDING OFF.

A BOARDING LADDER is a set of steps temporarily or permanently fitted over the side or stern of a boat to assist persons coming aboard from a low pier or float. A SWIMMING LADDER is much the same, except that it extends down into the water.

GRAB RAILS are hand-holding fittings mounted on cabin tops or sides, or in the interiors of boats, for personal safety when moving around the boat both on deck and below.

MAGNETIC COMPASSES are mounted at the control station, often in binnacles. Compasses are swung in GIMBALS, pivoted rings that permit the compass BOWL and CARD to remain relatively level regardless of the boat’s motion. To enable the helmsman to steer a COMPASS COURSE, a LUBBER’S LINE is marked on the inside of the compass bowl to indicate direction of the vessel’s bow (see Chapter 13 for more on compasses).

A LEAD (pronounced led) LINE is a length of light rope with a weight (the lead) at one end and markers at accurately measured intervals from that end. It is used for determining the depth of water alongside a vessel. A DEPTH SOUNDER is an electronic device for determining the depths; often such devices are referred to as “Fathometers”—a term that was originally the trademark of one manufacturer of electronic depth sounders (see Chapter 16). Boats frequently used in shallow waters may be equipped with a long, slender SOUNDING POLE, with depth in feet and fractions marked off from the lower end; there may be a special mark indicating the craft’s draft.

A BAROMETER is often carried aboard a boat; it measures and indicates atmospheric pressure. A BAROGRAPH records changing atmospheric pressure. Knowledge of the amount and direction of change in atmospheric pressure is useful in predicting changes in the weather (see Chapter 24).

A BINOCULAR is a device, usually hand-held, for detecting and observing distant objects. Separate sets of lenses and prisms enable the user to see with both eyes at the same time. (The term is properly singular, as in “bicycle,” but the plural form, “pair of binoculars,” for a single unit is often mistakenly used.)

A WINCH is a mechanical device, either hand or power operated, for exerting an increased pull on a line or chain, such as an anchor line or a sailboat’s halyards or sheets.

Ropes & Lines

Generally speaking, the term ROPE is little used aboard a boat; the correct term is LINE. “Rope” may be bought ashore at the store, but when it comes aboard a vessel and is put to use it becomes “line.” MARLINESPIKE SEAMANSHIP is the term applied to the art of using line and the making of KNOTS, BENDS, HITCHES, and SPLICES (see Chapter 23, which is devoted to this important subject).

Lines used to secure a boat to a shore structure are called MOORING LINES or DOCK LINES. BOW LINES and STERN LINES lead shoreward and keep the boat from drifting out from the shore. SPRING LINES lead aft from the bow or forward from the stern to prevent the boat from moving ahead or astern; refer to Figure 6-23.

A PAINTER is a line at the bow of a small boat, such as a dinghy, for towing or making fast. The line by which a boat is made fast to a mooring buoy is called a PENNANT (sometimes PENDANT). The pennant is SLIPPED when it is cast off so the boat can get underway. A pennant is also a flag (see Figure 1-32).

Lines have STANDING PARTS and HAULING PARTS. The standing part is the fixed part, the one that is made fast; the hauling part is the one that is taken in or let out as the line is used. Lines are FOUL when tangled, CLEAR when ready to run freely. Ends of lines are WHIPPED, or SEIZED, when twine or thread is wrapped around them to prevent strands from untwisting, or UNLAYING. Ragged ends of lines are said to be FAGGED.

HEAVING LINES are light lines, usually with a knot or weight at one end to make it easier to throw them farther and more accurately. A knot that encloses a weight at the end of a heaving line is called a MONKEY’S FIST.

HAWSERS are very heavy lines in common use on tugboats and larger vessels.

Flags

Strictly speaking, a vessel’s COLORS are the flag or flags that it flies to indicate its nationality, but the term is often expanded to include all flags flown. An ENSIGN is a flag that denotes the nationality of a vessel or its owner, or the membership of its owner in an organization (other than a yacht club).

A BURGEE is a triangular, rectangular, or swallow-tailed flag usually denoting yacht club or similar unit membership. A PENNANT is a flag, most often triangular in shape, used for general designating or decorative purposes.

The HOIST of a flag is its inner vertical side; also its vertical dimension. The FLY is its horizontal length from the hoist out to the free end; see Figure 1-32. The UNION is the upper portion near the hoist—in the U.S. national flag, the blue area with the white stars. The UNION JACK is a flag consisting solely of the union of the national flag (see Chapter 25 for more on flags and how they should be flown).

Figure 1-32 The principal parts and dimensions of a flag are shown here. For most flags the ratio between the hoist and the fly is 2:3, but this will vary with pennants. Flags should always be flown correctly.

Terms Used in Boating Activities

In addition to the numerous terms for the boat itself, there are many others to be learned in connection with boating in general. The list of these is virtually endless, and those that follow are only the more basic and often-used ones.

Docks, Piers & Harbors

There is a difference between strict definition and popular usage by many in boating for the term “dock.” Properly speaking, a DOCK is the water area in which a boat lies when it is MADE FAST to shore installations—and “made fast” is the proper term rather than “tied up.” In boating, however, the term “dock” is usually applied, albeit incorrectly, to structures bordering the water area in which boats lie. TO DOCK a vessel is to bring it to a shore installation and make it fast.