Figure 3-01 Standard safety equipment includes life jackets (Type I inherently buoyant and inflatable and Type III and Type IV flotation aids are shown). Other safety equipment pictured: an emergency signal kit, fire extinguisher, handheld VHF radio, horn, binocular, searchlight, flashlight, and a hand bearing compass.

Legally Required Gear That Your Boat Must Carry • The Additional Items That Add to Your Safety • Optional Gear That Provides Comfort & Convenience

Although most manufacturers supply the basic equipment required by law, and often many other useful items, few new or used boats come with everything needed—or desired—for safe, enjoyable boating. You should select the additional gear that is best suited for your boating needs.

Categories of Equipment

Equipment for a boat can be divided into three categories for separate consideration. These groupings are:

Equipment Required by Federal, State, or Local Law This list is surprisingly limited. It has little flexibility; items are strictly specified and usually must be of an “approved” type.

Additional Equipment for Safety & Basic Operations This is gear not legally required, but includes items that could be considered necessary for normal boat use.

Equipment for Comfort & Convenience This is gear that is not necessary, but adds to the scope and enjoyment of your boating.

Factors Affecting Selection

In all three categories, the items and quantities will vary with the size of the craft and the use made of it, with the legally required items determined in most cases by the “class” of boat (see Chapter 2,), as set by the Motorboat Act of 1940 (MBA/40). Other factors, such as the amount of electrical power available on board, cost, etc., will also affect equipment selection.

LEGALLY REQUIRED EQUIPMENT

The Federal Boat Safety Act of 1971 (FBSA/71; see Chapter 2,) requires various items of equipment aboard boats. The specific details are spelled out in regulations stemming from MBA/40 and are published in a Coast Guard booklet, “A Boater’s Guide to the Federal Requirements for Recreational Boats.” Go to www.uscgboating.org and click on Regulations to learn more. This site provides a wealth of useful information under a total of ten main subject headings.

Note that the FBSA/71 regulates the equipment of all boats including sailboats without mechanical propulsion, even though the regulations temporarily retained from the MBA/40 are in terms of “motorboats.” The 1940 act and its regulations remain effective for commercial vessels, such as diesel tugboats, which are not subject to the 1971 law.

State Equipment Regulations

According to Title 46, Section 4306 of the U.S. Code, no state or political subdivision may establish a performance or other safety standard that is not identical to the federal standards for boating safety and equipment set forth in the FBSA/71. The intent is to provide uniform standards nationwide.

The FBSA/71 allows states and their political subdivisions, such as counties or cities, to have requirements for additional equipment beyond federal requirements if needed to meet “uniquely hazardous conditions or circumstances” in a state or local area. The federal government retains a veto over such additional state or local requirements.

Required Equipment as a Minimum

Regard the legal requirements as a minimum. If a particular boat is required to have two fire extinguishers, for example, two may satisfy the authorities, but a third might be desirable, even necessary, to ensure that one is available at each location on board where it might be needed in a hurry. Two bilge vents may meet the regulations, but four would certainly give greater safety. Think “safety,” not just the minimum in order to be “legal.”

Nonapproved Items as Excess

Some boaters carry items of equipment no longer approved—older, superseded types, or items never approved—as “excess” equipment in addition to the legal minimum of approved items. This is not prohibited by regulations, but it may give a false sense of protection. The danger of reaching for one of these substandard items in an emergency must be recognized and positively guarded against. Some obsolete items of safety equipment, such as carbon tetrachloride fire extinguishers, are actually hazardous on a boat, and should never be on board.

Lifesaving Equipment

Boating is not inherently unsafe, but any time anyone goes boating there’s a chance of falling overboard or the craft sinking—a small chance to be sure, but it does exist. A LIFE JACKET—commonly called a PERSONAL FLOTATION DEVICE or PFD—is among the most essential safety items that can be on any boat. More importantly, they must be used. Accident data shows that 74 percent of deaths in boating accidents result from drowning, and 86 percent of those drowning were not wearing a life jacket. Many of these deaths were avoidable. An average adult needs additional buoyancy (the force that keeps you from sinking in the water) of 10 to 12 pounds (4.5 to 5.4 kg) in order to remain afloat. All PFDs approved by the U.S. Coast Guard and the Canadian Department of Transportation provide more than this amount of buoyancy. PFDs also provide some protection against another cause of boating accident casualties—hypothermia.

Legal Requirements

USCG regulations require that all recreational boats subject to their jurisdiction, regardless of means of propulsion—motor, sails, or otherwise—must have on board a Coast Guard–approved PFD for each person on board. There are a few quite minor exceptions, such as sailboards, racing shells, rowing sculls, and racing kayaks. Under federal law, sailboards are not classified as “boats” and therefore are exempt, but state laws may require PFD use. Foreign boats temporarily in U.S. waters are also exempted. “Persons on board” include those in tow, such as water-skiers. The PFDs must be in serviceable condition.

An additional federal requirement provides that all children under the age of 13 years must wear an appropriate USCG-approved PFD unless the child is belowdecks or in an enclosed cabin, or the craft is not underway; no size or type is specified for the boat. However, many states have their own laws that may differ in age limits, size or type of vessel, or its underway status, etc. If a state has established regulations governing when children must wear PFDs, those requirements supersede the federal rule in that state’s waters and will be enforced by all authorities.

More stringent requirements are placed on vessels carrying passengers for hire (any number) than are applied to recreational boats.

Coast Guard approval means that the design and manufacture of the PFD has met certain standards of buoyancy and construction. Many available PFDs will provide more than the minimum buoyancy.

Types of Personal Flotation Devices

Coast Guard–approved personal flotation devices are marked with a PFD “type” designation and descriptive name to indicate to the user the performance level that the device is intended to provide. Types I, II, III, and IV PFDs are WEARABLE, and Type IV PFDs are THROWABLE. These type designations have proved confusing, however, and in 2014 the Coast Guard issued new regulations that will allow manufacturers to develop new, clearer standards. The new regulations do not change the number of wearable or throwable PFDs that are required, nor will they affect previously purchased PFDs; these may be used as long as they are in serviceable condition. Until new standards are developed and PFD labels change, stores will continue to sell PFDs marked with the Coast Guard type codes.

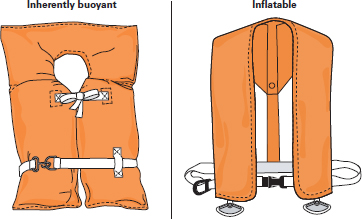

Type I PFD (Off-Shore Life Preserver or Life Jacket) is designed to turn most unconscious persons from a face-downward position in the water to a vertical, face-up or slightly backward position, and to maintain that person in that position, increasing the chances of survival. A Type I PFD is highly desirable for all open, rough, and remote waters, especially for cruising in areas where there is a probability of delayed rescue. This type of PFD is the most effective of all types in rough water. A Type I PFD is, however, somewhat less “wearable” than the other types, except for the Type I INFLATABLE PFDs now approved by the Coast Guard; see Figure 3-02.

Figure 3-02 A Type I personal flotation device is the best—suitable for all waters and needed for rough seas. It is designed to turn most unconscious wearers to a face-up position.

A Type I PFD is available in two sizes—adult (individual weighing 90 pounds (40.8 kg) or more) and child (less than 90 pounds). Each Type I will be clearly marked as to its size; a child size is not suitable for an infant. A Type I PFD must have at least 22 pounds (10 kg) buoyancy for adult size and 11 pounds (5 kg) for child’s size.

Type II PFD (Near-Shore Buoyancy Aid) is designed to turn the wearer to a vertical, face-up and slightly backward position in the water. The turning action is not as great as with a Type I, and will not turn as many persons as a Type I under the same conditions; note the lack of the qualification “unconscious,” although some Type IIs may have a flotation collar that will assist in such turning. Tests have shown that a Type II does not provide adequate safety in rough water, and it is intended for use in calm inland waters where there is a good chance of quick rescue; see Figure 3-03.

Figure 3-03 A Type II personal flotation device is also called a Near-Shore Buoyant Vest and should only be depended upon where there is a good chance of quick rescue. This will turn some unconscious wearers face up, but its turning action is less than a Type I; it is, however, somewhat more comfortable to wear.

Type II PFDs are available in four sizes: Adult weighing more than 90 pounds (40.8 kg); Youth weighing 50 to 90 pounds (22.6 to 40.8 kg); Child weighing 30 (13.6 kg) to 50 pounds, and Infant (less than 30 pounds). In addition, some models are sized by chest measurement. A Type II PFD must have buoyancy of at least 15.5 pounds for adult size, 11 pounds for youth size, or 7 pounds (3.2 kg) for child and infant sizes. Type II and Type III (below) inflatables are authorized for use only by persons at least 16 years of age.

Type III PFD (Flotation Aid) is designed so that the wearer can assume a vertical or slightly backward position and be maintained in that position with no tendency to turn face down. The Type III can be the most comfortable to wear and is available in a variety of styles that match such activities, as skiing, fishing, canoeing, and kayaking. It is a suitable choice for any activity in which it is especially desirable to wear a life jacket because the wearer is likely to intentionally enter the water. In-water trials have shown, however, that while a Type III jacket will provide adequate support in calm waters, it may not keep the wearer’s face clear in rough waters; this limitation should be kept in mind in the selection and use of this device; see Figure 3-04.

Figure 3-04 A Type III personal flotation device is a “flotation aid”—it should be used only in calm protected waters or where there is assurance of a quick rescue. A wearer must place himself in a face-up position; there is no inherent turning action as in Types I and II. It is generally the most comfortable to wear.

Type III PFDs must have at least 15.5 pounds of buoyancy. This is the same buoyancy as the Type II, but note that there is no turning requirement or protection for a person who becomes unconscious while in the water. Like Type II PFDs, Type IIIs are for use in inland waters when quick rescue is likely. One model has pockets with various items to aid detection and rescue, including a flashlight, flares, floating distress flag, and signaling mirror.

Type IV PFD (Throwable device) is designed to be grasped by the user, rather than worn, until rescue; it is typically thrown to a person who has fallen overboard. It is designed for use in calm inland waters with heavy traffic, where help is always present. Type IVs are available in a variety of forms; see Figure 3-05 for some of these.

Figure 3-05 A Type IV personal flotation device is a throwable PFD; it can take many shapes and forms. Shown above are a life ring buoy, a horseshoe buoy, and a cushion. Type IV PFDs are intended to be grasped rather than worn, and hence are of no value to an unconscious person.

Buoyant cushions are made of thick foam material in plastic cases measuring approximately 15 inches square by 2 inches thick. There are two grab straps on opposite sides for holding the PFD to your chest. Never wear a cushion on your back.

Ring buoys have rope around the circumference for holding onto the device. Standard sizes are 20 inches (51 cm), 24 inches (61 cm), and 30 inches (76 cm) in outside diameter. Life rings of 18.5 inches (47 cm) diameter have been approved under the “special purpose water safety buoyant device” category and are authorized for use on boats of any size that are not carrying passengers for hire.

Horseshoe buoys are throwable devices commonly found on sailboats. Their open side makes it easier to get “inside” the PFD.

A Type IV PFD cushion must have at least 20 pounds (9.1 kg) of buoyancy; ring buoys must have from 16.5 pounds (7.5 kg) to 32 pounds (14.5 kg) depending upon diameter.

Type V PFD (Special Use Device) is any device designed for a specific and restricted use. It may be carried instead of another type only if used according to the approval condition stated on the device’s label, which often requires that it be worn if used to satisfy the PFD regulation. A Type V PFD may provide the performance of a Type I, II, or III device as marked on the label. Varieties include exposure suits, work vests, and sailboard vests. Some Type V devices provide significant hypothermia protection.

Styles of Flotation Devices

Coast Guard regulations recognize a number of different styles of PFDs and contain specifications that must be met or exceeded for each. Each device must be marked with its approval number and all other information required by the specifications.

Offshore Life Preservers Type I PFDs are available in jacket, bib, or inflatable style; refer to Figure 3-02. The flotation material of the jacket type is pads of kapok or fibrous glass material inserted in a cloth cover fitted with the necessary straps and ties. Kapok or fibrous glass must be encased in sealed plastic film covers. Type I PFDs of the bib type may be of cloth containing unicellular plastic foam sections of specified shape, or they may be uncovered plastic foam material with a vinyl dip coating. The bib type must have a slit all the way down the front and have adjustable body straps. This is the type commonly used on passenger ships and craft because of easier stowage than the jacket type.

Type I inflatable PFDs approved for use on recreational craft must have at least two inflation chambers, each of which must independently meet all of the in-water performance requirements for that PFD. One of the inflatable compartments must have an automatic or an automatic/manual CO2 inflator system, and the other must have at least a manual CO2 inflation system. All three designs of Type I PFDs have patches of reflecting material to aid in the location of a person in the water at night.

Type I life jackets are individually inspected after manufacture. They are marked with the type, manufacturer’s name and address, and USCG approval number, plus a date and place of inspection together with the inspector’s initials. All Type I PFDs are now required to be INTERNATIONAL ORANGE in color.

Near Shore Buoyancy Aids Type II PFDs include BUOYANT VESTS that come in many styles and colors. They use the same flotation materials as life preservers, but vests are smaller and provide less buoyancy, and hence somewhat less safety, for a person in the water. Recent tests suggest that they are not entirely dependable for prolonged periods in rough water. The Type II is usually more comfortable to wear than a Type I, and remember, a PFD that is not worn is less likely to help you in an emergency! Boaters may prefer to use the Type II where there is a probability of quick rescue, such as areas where it is common to find craft and persons engaged in boating, fishing, and other water activities.

Buoyant vests are marked with the model number, manufacturer’s name and address, approval number, and other information. These water safety items are approved by lot and are not individually inspected and marked.

Inflatable PFDs are a solution to the common problem of boaters who do not wear conventional PFDs as they should because many are uncomfortable and restrict activities. (Keep in mind that 86 percent of the people who drown in boating accidents might have been saved if they had been wearing a life jacket.) The inflatable PFD is much less bulky than conventional PFDs. Because many boaters find them more comfortable, they are more likely to be worn; see Figure 3-06. Most are vest types, but there are also approved belt-pouches. In addition to Type III inflatables, there are also Type V PFDs that may be classed as either Type II or III as determined by their buoyancy—22 pounds (10 kg) to 34 pounds (15.4 kg).

Figure 3-06 Inflatable PFDs can be either manual inflation (Type III) or manual/automatic (Type V, with Type II performance). Though expensive, these are the most comfortable for routine wearing but must be worn to count toward the legal requirement, if the label so states. Inflatables are authorized for use only by persons at least 16 years of age.

Inflatable PFDs are available in either manual or automatic styles, depending on the inflation action. Manual models require action by the wearer to activate the small compressed-gas (CO2) cylinder. Automatic models inflate when a sensing device becomes wet; they can also be activated manually. Both models can be inflated by blowing into tubes.

Inflatable PFDs are not for everyone. They should be used only by persons who can swim; they are not authorized for persons under 16 years of age. They are considerably more expensive than traditional PFDs. They require maintenance (the Coast Guard withheld approval for many years because of concern that boaters would not provide adequate maintenance). After use, inflatable PFDs must be rearmed immediately with a new cartridge; if automatic style, the activating unit must be replaced. Some automatic models will have a spare cartridge in a pocket so that in the case of accidental activation, the PFD can be rearmed as a manual model.

Caution: Automatic inflatable PFDs should not be worn in cabins or other enclosed compartments. An unexpected capsize or flooding could actuate them and cause difficulties in exiting, possibly even making egress impossible.

Special Purpose Devices are a category of PFDs that may be either Type II or Type III if they are designed to be worn; they are Type IV if designed to be thrown.

The design of SPECIAL PURPOSE WATER SAFETY BUOYANT DEVICES is examined and approved by recognized laboratories (such as Underwriters Laboratories; see Chapter 11); this approval is accepted by the Coast Guard. These devices are labeled with information about intended use, the size or weight category of the user, instructions as necessary for use and maintenance, and an approval number. Devices to be grasped rather than worn will also be marked “Warning: Do Not Wear on Back.”

Buoyant Cushions are the most widely used style of Type IV PFD. Although adequate buoyancy is provided—actually more than by a buoyant vest—the design of cushions does not provide safety for an exhausted or unconscious person; see Figure 3-07.

Buoyant cushions are approved in various shapes and sizes, and may be of any color. Approval is by lot and number as indicated on a label on one side, along with the same general information as for buoyant vests. All cushions carry the warning not to be worn on the back.

Figure 3-07 By far the most common Type IV personal flotation device is the buoyant cushion. It must always be remembered that it is primarily a lifesaving device, not just another cushion on board. The straps should be grasped, but a person’s arms may be placed through the straps to hold the device in front of him, never on the back.

Life Rings are another style of Type IV PFD, more properly called LIFE RING BUOYS, which may be of cork, balsa wood, or unicellular plastic foam. The ring is surrounded by a light grab line fastened at four points; refer to Figure 3-05.

Balsa wood or cork life ring buoys are marked as Type IV PFDs and with other data generally similar to life preservers. They may be either international orange or white in color.

Rings of plastic foam with special surface treatment will carry a small metal plate with approval information including the inspector’s initials. Ring buoys of this style may be either international orange or white in color.

Some skippers letter the name of the boat on their ring buoys; this is not prohibited by the regulations.

Horseshoe Ring Buoys are another type of marine buoyant device, Type IV, often found on cruising sailboats and almost always on larger racing sailboats for man-overboard emergencies. These are made of unicellular foam encased in a vinyl-coated nylon cover. The shape is aptly described by the device’s name—it is much easier to get into in the water than a ring buoy. These are normally carried vertically in special holders near the stern of the boat; some holders are designed to release the horseshoe ring quickly by merely pulling a pin on a cord. To facilitate the recovery of the victim, these rings are often equipped with special accessories at the end of a short length of line—a small float with a slender pole topped with a flag (and, in some cases, with a radar reflector), an electric flashing light that automatically comes on when floating upright in the water, a small drogue to slow the rate of drift to more nearly that of a man in the water—all or a combination of these items.

Hybrid PFDs combine inherent internal foam buoyancy with the capability of being inflated to a greater buoyancy. These are available in adult, youth, and child sizes. The inherent buoyancy ranges from 10 pounds (4.6 kg) to 7.5 pounds (3.4 kg) depending upon size, with inflated buoyancies of 22 pounds (10 kg) to 12 pounds (5.4 kg). The hybrid PFD is less bulky and more comfortable to wear than other PFDs, yet the device has at least some initial support in case of accidental falls overboard with the victim possibly unconscious—and much greater buoyancy if the person is conscious and capable of inflating the hybrid PFD.

Unless the person concerned is within an enclosed space, hybrid PFDs are acceptable toward the legal requirements but only if they are being worn, if the label so states. These devices should be assigned to a specific person and fitted to that individual; they should be tried on in the water. Hybrid PFDs are not desirable for use by guests; guests should have Types I, II, or III.

Buoyant Work Vests are classed as Type V PFDs. These are items of safety equipment for crewmembers and workmen when employed over or near water under favorable conditions and properly supervised. Such PFDs are not normally approved for use on recreational boats.

PFD Requirements by Boat Size

All recreational boats must have on board at least one approved wearable personal flotation device of Type I, II, III, or V for each person on board. Though they need not be worn, except with some Type Vs, they must be near at hand. A Type V must provide the performance of a Type I, II, or III (as marked on its label) and must be used in accordance with that label.

Boats 16 feet or more in length must additionally have on board at least one Type IV “throwable” PFD.

All PFDs must be Coast Guard approved, in good condition of appropriate size for their intended users, and legibly marked with their types.

MAINTENANCE FOR YOUR PFDs

It is not only a requirement of Coast Guard regulations to maintain your life jackets in good condition; it is common sense—your life may depend on them some day! So take care of them, and remember that a PFD, like any other item of equipment on your boat, eventually wears out and must be replaced.

• You and each person in your regular crew should have a specifically assigned PFD marked with their name. It should be tried regularly in shallow water. It should hold its wearer comfortably so that he or she can breathe easily.

• After each use, each PFD should be airdried thoroughly away from any direct heat source. Then store it in a dry, well-ventilated, easily accessible place on board the boat.

• Check at least once a year for mildew, loose straps, or broken zippers (if applicable). Clean with mild soap and running water; avoid using strong detergents or chemical cleaners, and do not dry clean. Check PFD covers for tears—a cover that has torn due to weakened fabric is unserviceable; a weak cover could split open and allow the flotation material to be lost. Badly faded colors that should be bright can be a clue that deterioration has occurred. Compare fabric color where it is protected—under a strap, for example—to where it is exposed. A PFD with a UV-damaged fabric cover should be replaced without delay. Another test is to pinch the fabric between thumb and forefinger and try to tear it. If the cover can be torn, the life jacket should be replaced.

• Check PFDs that use kapok-filled bags for buoyancy. Make sure that the kapok has not hardened and that there are no holes in the bags. Squeeze the bags and listen for an air leak. If water has entered a bag, the kapok will eventually rot. Destroy and replace any PFD that fails these tests.

• Avoid contact with oil or grease, which sometimes causes kapok materials to deteriorate and lose buoyancy

• Avoid kneeling on PFDs; do not use them for fenders.

Stowage of PFDs

The best “storage” of your PFD is on your person while your boat is underway—the need for it may arise suddenly with no time to find it and put it on. A wearable PFD may save your life, but only if you wear it.

When not being worn, it is best that PFDs be stored out of direct sunlight. Coast Guard regulations are very specific about stowage of personal flotation devices. Any required Type I, II, or III (or acceptable Type V) PFD must be “readily accessible.” Any Type IV PFD required to be on board must be “immediately available.” These rules are strictly enforced.

The PFDs must also be in “serviceable condition.” Inspect your PFDs at least annually, and replace any that show signs of deterioration, usually found in the covering or straps.

State Requirements

Except as regards inflatable and hybrid PFDs and children under 13, federal regulations require flotation devices to be on board, but not necessarily worn. State regulations may identify additional situations where PFDs must be worn. A majority of states now require that children wear flotation devices while boating, in some cases even in the two circumstances exempted from the federal mandate (i.e., when below decks or when the boat is not underway); the upper age limits for these requirements vary among states from 5 to 12.

It is critical that a child’s PFD be of the proper size and fit and that it be tried out in a safe place such as a swimming pool. The child must not be able to slip out of the device; crotch straps are an important feature for children’s flotation devices.

Fire Extinguishers

All hand-portable and semi-portable fire extinguishers and fixed fire extinguishing systems must be of a type that has been approved by the Coast Guard. Such extinguishers and extinguishing systems will be clearly labeled with information as to the manufacturer, type, and capacity. (See below for information on type and size.)

Coast Guard approval of hand-portable extinguishers requires that they be in approved marine-type mounting brackets.

Figure 3-08 Most fire extinguishers on boats will be portable dry-chemical units. These must have a pressure gauge, which should be checked regularly. Extinguishers must be USCG approved and mounted on an approved bracket.

Types of Fire Extinguishers

Fire extinguishers, including those for boats, are described in terms of their contents—the actual extinguishing agent.

Dry Chemical This type of extinguisher is widely used because of its convenience and relatively low cost. The cylinder contains a dry chemical in powdered form together with a propellant gas under pressure. Coast Guard regulations require that such extinguishers be equipped with a gauge or indicator to show that normal gas pressure exists within the extinguisher; do not carry one that does not meet this requirement, it is not USCG approved; see Figure 3-08.

The dry chemical in these extinguishers has a tendency to “pack” or “cake.” Mount them where there is a minimum of engine vibrations; invert and shake them every month or two.

Carbon Dioxide Some boats have carbon dioxide (CO2) extinguishing systems; such units are advantageous as they leave no messy residue to clean up after use, and they cannot cause harm to the interior of engines as some other types may. This type of extinguishing agent may be used as a fixed system installed in an engine compartment, operated either manually or automatically by heat-sensitive detectors. Semi-portable extinguishers (wheeled carts) will be seen on some marina piers and in boatyards. Carbon dioxide extinguishers consist of a cylinder containing this gas under high pressure, a valve, and a discharge nozzle, sometimes at the end of a short hose. The state of charge of a CO2 extinguisher can only be checked by weighing the cylinder and comparing this figure with the one stamped on or near the valve. See Chapter 11, for further details on the maintenance of CO2 extinguishers.

Vapor Systems Other chemical vapors with a fire extinguishing action are available. Halon 1301 is a colorless, odorless gas that stops fire instantly by chemical action. It is heavier than air and sinks to lower parts of the bilge. Unfortunately, Halon has been found to be an ozone-depleting agent, and the federal Clean Air Act of 1994 prohibited it from being manufactured. In addition, in 1998 the EPA required that Halon equipment must be properly discharged at the end its useful life by sending it to a Halon recovery facility meeting EPA standards. It is not illegal, however, to possess, use, or even replace Halon manufactured before 1994. Many new fire-fighting agents that replace Halon are clean, meaning they do not deplete ozone in the environment and they do not leave a residue or require a cleanup after they extinguish a fire..

An alternative chemical for vapor systems is FE-241; however, this gas is toxic and must not be used in occupied spaces. It is used in engine compartments, with the size of extinguisher matched to the volume of the space to be protected. To avoid damage to engines, especially diesels, it should be used with an automatic shutdown device. FM-200 is another chemical for fire extinguishers that is considered safe for use in occupied spaces, but is significantly more expensive.

The state of charge of a vaporizing liquid extinguisher can only be checked by weighing the cylinder and comparing this figure with the one stamped on or near the valve; see Chapter 11, for further details on the maintenance of Halon and FE-241 extinguishers.

Foam Aqueous film foam forming (AFFF) extinguishers are legally acceptable on boats, but this type is rarely used, as it leaves a residue that is difficult to clean up after use and may require a partial engine disassembly if discharged in an engine compartment.

Foam extinguishers are not pressurized before use and do not require tests for leakage. Such units contain water and must be protected from freezing. Foam extinguishers should be discharged and recharged annually.

Nonacceptable Types Vaporizing-liquid extinguishers, such as those containing carbon tetrachloride and chlorobromomethane, are effective in fighting fires but produce highly toxic gases. They are not approved for use on motorboats and should not be carried even as excess equipment because of their danger to the health—or even life—of a user in a confined space.

Classification of Extinguishers

Fires are classified—according to the general type of material being burned—into four categories, three of which are of concern to boaters: A (combustible materials), B (flammable liquids), C (electrical components); see Chapter 12. The fourth category—D (flammable metals, such as magnesium)—does not concern boaters.

Fire extinguishers are similarly classified as to type and, commonly, are placed in size groups. I (the smallest) through V (largest). Only the two smallest sizes, I and II, are hand portable; size III is a semi-portable fire extinguishing system, and IV and V are too large for consideration here.

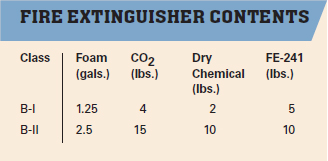

In 2016, the Coast Guard issued new regulations that will eventually replace the CG codes on the labels with the more familiar Underwriter Laboratories (UL) ratings, which already appear on many extinguishers. The UL rating provides a better guide to extinguisher capacity. The Coast Guard's B-I rating (see Figure 3-09) will be replaced by “5-B,” which is equivalent to a UL 5-B:C rating. The B-II rating will be replaced by “20-B,” which is equivalent to a UL 20-B:C rating.

Figure 3-09 Fire extinguishers that are approved by the Coast Guard under pre-2016 regulations for use on boats are hand-portable, B-I or B-II classification, and have the characteristics shown above.

The primary fire hazard on boats results from flammable liquids, so Type B extinguishers are specified. (Some B extinguishers have adequate or limited effectiveness on other classes of fire; ABC extinguishers are effective on all three classes. Other extinguishers should not be used on certain types of fires, such as foam on Class C electrical fires.).

The new regulations affect vessels built after August 5, 2016, but do not require existing fire extinguishers to be replaced as long as they are serviceable and properly maintained. In addition, it will take some time before the new standard appears on fire extinguisher labels, and in the meantime stores will continue to sell fire extinguishers that are marked with the Coast Guard size codes I and II. When replacing an existing Class I fire extinguisher, if the new one has Coast Guard Class I on the label, make sure it also has a UL 5-B:C rating or higher. Similarly, when replacing an existing Class II fire extinguisher, if the new one has Coast Guard Class II on the label, make sure it also has a UL 20-B:C rating or higher.

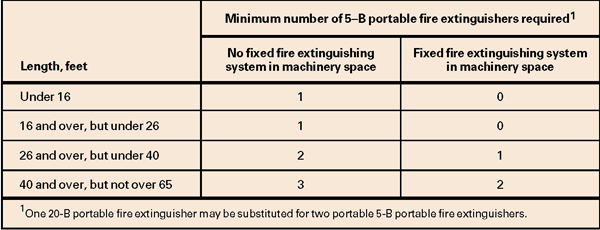

Figure 3-10 Fire extinguisher requirements.

Requirements on Boats

Fire extinguishers on boats must be specifically marked “Marine Type U.S. Coast Guard Approved.”

Class A (under 16 feet) and Class 1 (16 to under 26 feet or 7.9 m) boats must have at least one type 5-B (UL 5-B:C or higher) hand-portable fire extinguisher, except that boats of these classes with outboard motors and portable fuel tanks, not carrying passengers for hire and of such open construction that there can be no entrapment of explosive or flammable gases or vapors, need not carry an extinguisher. See Figure 3-10.

A fire extinguisher is required on boats under 26 feet (7.9 m) in length powered with outboard motors if one or more of the following conditions exist; see Figure 3-11:

• Closed compartment under thwarts or seats in which portable fuel tanks may be stored.

• Double bottoms not sealed to the hull or which are not completely filled with flotation material.

• Closed living spaces.

• Closed storage compartments in which combustible or flammable materials are stowed.

• Permanently installed fuel tanks. (To avoid being considered as “permanently installed,” tanks must not be physically attached in such a manner that they cannot be moved in case of fire or other emergency. The size of the tank in gallons is not a specific criterion for determining whether it is a portable or a permanently installed tank. If the weight of a fuel tank is such that persons on board cannot move it, the Coast Guard considers it to be permanently installed.)

Figure 3-11 If a craft has one or more of the enclosed spaces identified above, Coast Guard regulations require that it must carry at least one fire extinguisher.

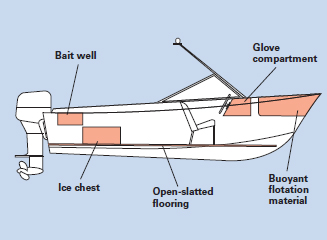

The following conditions do not, of themselves, require that fire extinguishers be carried; see Figure 3-12:

• Bait wells

• Glove compartments

• Buoyant flotation material

• Open-slatted flooring

• Ice chests

Class 2 boats (26 feet to under 40 feet long) must carry at least two 5-B approved hand-portable fire extinguishers, or at least one 20-B unit.

Class 3 boats (40 to 65 feet long) must carry at least three 5-B approved hand extinguishers, or at least one 20-B unit plus one 5-B unit.

Boats with fixed extinguisher systems in the engine compartment may have the above minimum requirement for their size reduced by one 5-B unit. The fixed system must meet Coast Guard specifications.

Exemptions Motorboats propelled by outboard motors, while engaged in a previously arranged and announced race (and such boats designed solely for racing, while engaged in operations incidental to preparing for racing) are exempted by Coast Guard regulations from any requirements to carry fire extinguishers.

Figure 3-12 A boat of open construction, with no enclosed spaces other than those shown here, need not have a fire extinguisher on board, but one is desirable for safety.

Keeping Safe

Don’t merely purchase and mount fire extinguishers and then forget all about them. All types require some maintenance and checking; see Chapter 11 for guidance in keeping up the level of fire protection you gain when first installing new extinguishers.

All members of your regular crew, and any guests who may be aboard, should know the locations and operation of all fire extinguishers.

Never partially discharge a dry-chemical extinguisher with the idea of saving the balance of its contents for later use. There is almost always some powder left in the valve, and this will result in a slow leak of pressure, rendering the unit useless. Always recharge or replace fire extinguishers immediately after use. As the cost of recharging small extinguishers is almost the cost of a new one, replacement is the usual action.

Backfire Flame Control

Every inboard gasoline engine must be equipped with an acceptable means of BACKFIRE FLAME CONTROL. Such a device is commonly called a “flame arrester” and must meet Coast Guard specifications to be approved. Accepted models will be listed by manufacturer’s number in equipment lists or will have an approval number marked on the grid housing.

In use, flame arresters must be secured to the air intake of the carburetor with an airtight connection, have clean elements, and have no separation of the grids that would permit flames to pass through; see Figure 3-13. Fuel-injected engines without carburetors require a backfire flame arrester over the air intake to prevent exhaust valves from backfiring into the air chamber, which might cause a fire or explosion.

Figure 3-13 A backfire flame control is more widely known as a “flame arrester.” Coast Guard regulations require an approved model on every inboard gasoline engine. Elements must be kept clean, and grids must not have any separations that would let flames pass through.

An exception is made for boats constructed so that the fuel/air induction system is above the sides of the hull—typically craft used in connection with waterskiing—provided that specified conditions are met.

Ventilation Requirements

All motorboats, except open boats, that use fuel having a flashpoint of 110°F (43.3°C) or less—gasoline, but not diesel—must have ventilation for every engine and fuel tank compartment. Gasoline in its liquid and vapor states is potentially dangerous, but to enjoy safe boating, one need only follow Coast Guard regulations and use good common sense.

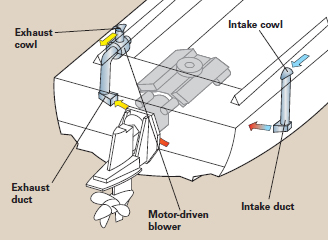

The Coast Guard requires mechanical ventilation blowers on all boats built after 31 July 1980 under regulations derived from the Motorboat Act of 1940; see Figure 3-14. Manufacturers must provide such equipment, and no person may operate such a boat that has a gasoline engine for propulsion, electrical generation, or mechanical power unless it has an operable ventilation system that meets the requirements. Thus the initial requirement is placed on the builder, but the owner has a continuing responsibility. Boats of “open construction” are exempted.

Figure 3-14 A powered ventilation system consists of one or more intake ducts plus one or more exhaust ducts with an exhaust blower. Each exhaust blower must draw from the lower one-third of the engine compartment but above the normal level of bilge water.

Open Construction Defined

The Coast Guard has prepared a set of specifications to guide the boat owner in determining whether his boat meets the definition of “open construction.” To qualify for exemption from the bilge ventilation regulations, the boat must meet all of the following conditions:

• As a minimum, the engine and fuel tank compartments must have 15 square inches of open area directly exposed to the atmosphere for each cubic foot of net compartment volume. (Net volume is found by determining total volume and then subtracting the volume occupied by the engine, tanks, and other accessories, etc.)

• There must be no long or narrow unventilated spaces accessible from the engine or fuel tank compartments into which fire could spread.

• Long, narrow compartments, such as side panels, if joining engine or fuel tank compartments and not serving as ducts, must have at least 15 square inches of open area per cubic foot through frequent openings along the compartment’s full length.

Sailboats are subject to the same ventilation requirements as powerboats if combustible fuel is carried on board.

Be Safe—Be Sure

If your boat is home-built or does not meet one or more of the specifications above, or if there is any doubt, play it safe and provide an adequate ventilation system. To err on the safe side will not be costly; it may save a great deal, perhaps even a life.

Natural Ventilation

Unless it is of open construction, a gasoline-engine-powered boat is required to have at least two ventilation ducts, fitted with cowls at their openings to the atmosphere, for each engine and fuel tank compartment. An exception is made for fuel tank compartments having electrical components that are “ignition protected” in accordance with Coast Guard standards and fuel tanks that are vented to the outside of the boat; see Figure 3-15.

Figure 3-15 A natural ventilation system is an arrangement of intake openings or ducts from the atmosphere (located on the outside of the hull), or from a ventilated compartment, or from a compartment that is open to the atmosphere. There are also one or more exhaust ducts.

VENTILATORS, DUCTS, and COWLS must be installed so that they provide for efficient removal of explosive or flammable gases from bilges of each engine and fuel tank compartment. To create a flow through the ducting system—at least when underway or when there is a wind—cowls (scoops) or other fittings of equal effectiveness are needed on all ducts. A wind-actuated rotary exhaust fan or mechanical blower is equivalent to a cowl or an exhaust duct.

Lack of adequate bilge ventilation can result in an order from a Coast Guard Boarding Officer for “termination of unsafe use” of the boat; see Chapter 2.

Ducts Required

Ducts are a necessary part of a ventilation system. A mere hole in the hull won’t do; that’s a vent, not a ventilator. “Vents,” the Coast Guard explains, “are openings that permit venting, or escape of gases due to pressure differential. Ventilators are openings that are fitted with cowls to direct the flow of air and vapors in or out of ducts that channel movement of air for the actual displacement of fumes from the space being ventilated.” Each supply and exhaust duct must extend to the lower third of the compartment and must be above the normal accumulation of bilge water.

Size of Ducts

Ventilation must be adequate for the size and design of the boat. There should be no constriction in the ducting system that is smaller than the minimum cross-sectional area required for efficiency. Where a stated size of duct is not available, the next larger size should be used.

Small Motorboats To determine the minimum cross-sectional area of the cowls and ducts of motorboats having small engine and/or fuel tank compartments, see Table 3-1, which is based on net compartment volume (as previously defined).

VENTILATION REQUIREMENTS FOR SMALL BOATS

| Minimum Inside Diameter for Each Duct (inches) |

|||

| Net Volume (cu. ft.) |

Total Cowl Area (sq. in.) |

One-Intake and One-Exhaust System |

Two-Intake and Two-Exhaust System |

| Up to 8 | 3 | 2 | – |

| 10 | 4 | 2¼ | – |

| 12 | 5 | 2½ | – |

| 14 | 6 | 2¾ | – |

| 17 | 7 | 3 | – |

| 20 | 8 | 3¼ | 2½ |

| 23 | 10 | 3½ | 2 ½ |

| 27 | 11 | 3¾ | 3 |

| 30 | 13 | 4 | 3 |

| 35 | 14 | 4¼ | 3 |

| 39 | 16 | 4½ | 3 |

| 43 | 19 | 4¾ | 3 |

| 48 | 20 | 5 | 3 |

Note: 1 cu. ft. = 0.028 cu. m; 1 in. = 2.54 cm; 1 cu. in. = 16.39 cu. cm

Table 3-1 Ventilation requirements for small boats.

Cruisers and Large Boats For most cruisers and other large motorboats, see Table 3-2, which is based on the craft’s beam; this is a practical guide for determination of the minimum size of ducts and cowls.

VENTILATION REQUIREMENTS FOR LARGE POWERBOATS

Two-Intake and Two-Exhaust System

| Vessel (feet) |

Beam Minimum Inside Diameter for Each Duct (inches) |

Cowl Area (sq. in.) |

| 7 | 3 | 7.0 |

| 8 | 31/4 | 8.0 |

| 9 | 31/2 | 9.6 |

| 10 | 31/2 | 9.6 |

| 11 | 33/4 | 11.0 |

| 12 | 4 | 12.5 |

| 13 | 41/4 | 14.2 |

| 14 | 41/4 | 14.2 |

| 15 | 41/2 | 15.9 |

| 16 | 41/2 | 15.9 |

| 17 | 41/2 | 17.7 |

| 18 | 5 | 19.6 |

| 19 | 5 | 19.6 |

Note: 1 cu. ft. = 0.028 cu. m; 1 in. = 2.54 cm; 1 cu. in. = 16.39 cu. cm

Table 3-2 Ventilation requirements for large powerboats.

Ducting Materials

For safety and long life, ducts should be made of nonferrous, galvanized ferrous, or sturdy high-temperature resistant nonmetallic materials. Ducts should be routed clear of, and protected from, contact with hot engine surfaces.

Positioning of Cowls

Intake cowls will normally face forward in an area of free airflow underway, and the exhaust cowl will face aft so that a suction effect can be expected.

The two cowls, or sets of cowls, should be located with respect to each other, horizontally and/or vertically, so as to prevent return of fumes removed from any space back into the same or any other space. Intake cowls should be positioned to avoid picking up vapors from fueling operations.

Combustion Air for Engines

Openings into the engine compartments for entry of air for the engine’s combustion air are in addition to requirements of the ventilation system.

Requirements for Boats

On boats built after 31 July 1980, each compartment having a permanently installed gasoline engine with a cranking motor for remote starting must be ventilated by a powered exhaust blower system unless it is of “open construction”. Each exhaust blower, or combination of blowers, must be rated at an airflow capacity not less than a value computed by formulas based on the net volume of the engine compartment plus other compartments open thereto.

The engine compartment—and other compartments open to it where the aggregate area of openings exceeds two percent of the area between the compartments—must also have a natural ventilation system.

There must be a warning label as close as practicable to the ignition switch that advises of the danger of gasoline vapors and the need to run the exhaust blower for at least four minutes and then check the engine compartment for fuel vapors before starting the engine.

Natural ventilation systems are also required for any compartment containing both a permanently installed fuel tank and any electrical component that is not “ignition protected” in accordance with existing Coast Guard electrical standards for boats; or a compartment that contains a fuel tank that vents into that compartment (highly unlikely); or one having a nonmetallic fuel tank that exceeds a specified permeability rate. The USCG regulations specify the required cross-sectional area of ducts for natural ventilation based on compartment net volume, and how ducts shall be installed.

The regulations above concern the manufacturer of the boat, but there is also a requirement placed on the operator that these ventilation systems be operable any time the boat is in use. Because such systems are so desirable, it is recommended that they be installed on any gasoline-powered motorboat or auxiliary; see also fuel vapor detectors in Chapter 11.

Requirements for Older Boats

On boats built before 1 August 1980, only natural ventilation is required—one intake cowl and duct extending from the atmosphere to a point at least midway to the bilge or below the carburetor; there must also be at least one exhaust cowl and duct extending from the atmosphere to the lower portion of the bilge (but not so low as to become blocked by normal bilge water levels). For such boats, there is no federal requirement as to the minimum duct size, but Coast Guard policy is that the smallest acceptable size is two inches for all boats.

If the boat is equipped with a bilge blower, its duct could serve as the exhaust duct for natural ventilation as well, provided the size of the duct is large enough and the flow of air is not obstructed by the fan blades. A separate duct is also acceptable.

Diesel-Powered Boats

Diesel fuel does not come within the Coast Guard’s definition of a “volatile” fuel, and thus bilge ventilation legal requirements are not applicable. It is, however, a sensible step to provide essentially the same ventilation system for your boat even if it is diesel-powered, particularly because diesel engines require a high volume of air for efficient combustion. Diesel fuel does not explode, but it does burn; a broken fuel line can cause a fire that could result in the total loss of your boat.

Visual Distress Signals

All boats of any type 16 feet (4.9 m} or more in length, and all craft of any size carrying six or fewer passengers for hire, must be equipped with approved VISUAL DISTRESS SIGNALS (VDS) at all times when operating on coastal waters. Boats engaged in regattas or racing, manually propelled boats, and sailboats less than 26 feet (7.9 m) in length and not equipped with propulsion machinery are not required to carry day signals, but must carry night signals when operating from sunset to sunrise.

There are two types of VDS: nonpyrotechnic, such as a special orange flag or an approved signaling light; and pyrotechnic, such as a red flare or smoke signal. If pyrotechnics are selected, there must be three such signals available to satisfy the requirement. If nonpyrotechnics are chosen, one day and one night signal will suffice. Thus the VDS requirement may be met by carrying three day and three night pyrotechnic signals or by carrying a special daytime flag and a special nighttime flashing light. Boats less than 16 feet (4.9 m) in length—with the exceptions noted above—must carry distress signals when operating at night. Day signals are not required on such boats but would be prudent to carry.

U.S. coastal waters are defined as the Great Lakes and the territorial seas (out to 24 miles from shore) plus any connected waters having an entrance that is wider than two nautical miles, extending inland to the first point at which the distance between shorelines narrows to less than two miles (see Chapter 2, for more on these definitions). Shorelines of islands or points of land within a waterway are considered in determining the distance between opposite shorelines.

Types of Visual Distress Signals

Visual distress signals are classified for day (D) or night (N) use, or for both (D/N). To meet the requirements, a boat must have an orange flag with special square-and-disc markings in black (D) and an S-O-S electric light (N); or three handheld or floating orange smoke signals (D), plus three flares (N); or three red flares of hand-held, meteor, or parachute type (D/N). Each signal must be legibly marked with a Coast Guard approval number or certification statement. It must be serviceable and not past any expiration date; see Figure 3-16. (Pyrotechnic signals will have an expiration date 42 months after manufacture.) Combinations of various flare types and smoke signals are acceptable. (The flares must carry an approval; older launchers may be used if still available.) In some states, a pistol launcher for flares may be considered a firearm and subject to licensing and other restrictions; check your local authorities before purchasing such a device. A unique “flag” is available that can be inflated to hold its full shape for constant maximum visibility; it can be used flat in the water to be seen from overhead.

Figure 3-16 Approved visual distress signals include hand-held flares, meteor and parachute flares, smoke signals, and others suitable for day or night use, or both.

All visual distress signals must be stowed so as to be “readily available.”

The legal requirements are a minimum; prudent skippers will carry additional and more robust signals to meet their particular needs.

Visual distress signals must not be displayed on the water except where assistance is needed because of immediate or potential danger to the persons on board. This allows tests and demonstrations to be made on the shore, but good judgment should be used to avoid false alarms—if there is any likelihood of reports being made to the local Coast Guard unit notify them by telephone or radio of your intended actions.

The use of pyrotechnic signals is not without hazard from the flame and hot dripping ash and slag. Hand-held flares must be held over the side and in such a way that hot slag will not drip on your hand or the deck or side of your boat. Pistollaunch flares should be fired downwind and at an angle of roughly 60° above the horizon, higher in stronger winds but never directly upward. In a distress situation, do not waste signals by setting them off when no other vessel is within sight.

If you are using a pistol-type launcher, check to make sure that the flares you have now or purchase later will fit—there have been small changes in the length of some flares, and not all will fit in all launchers.

Marine Sanitation Devices

The regulatory requirements for boat to have a marine sanitation device (MSD) were discussed in Chapter 2. This section will cover the various types of MSDs that must be installed to meet those requirements, and the level of treatment they provide.

Type I & Type II MSDs

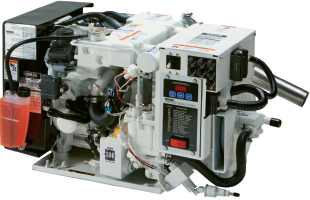

Type I and Type II marine sanitation devices are described in Coast Guard regulations as “flow-through” devices; the difference between the types is the level of treatment; see Figure 3-17.

Figure 3-17 Type I Marine Sanitation Devices are available that more than meet the EPA and Coast Guard requirements for overboard discharge of human wastes. This device macerates and disinfects sewage in a two-step process. The effluent contains no floating solids and is typically cleaner than the water in which the boat is floating.

The most common form is a MACERATOR-CHLORINATOR, which takes the discharge of a marine toilet, grinds up the solids to fine particles, treats the resultant waste with a disinfectant, and pumps the treated sewage overboard. Many MSDs dispense disinfectant from prefilled reservoirs. Others make their own disinfectant by using electricity to break down seawater, using the dissolved salt (NaCl, sodium chloride) to produce chlorine, the active disinfectant. In fresh or brackish waters, ordinary table salt may be placed in a dispenser to provide the necessary chemical.

A Type I MSD must be certified as being capable of discharging an overboard waste liquid that has a coliform bacterial count of not more than 1,000 per 100 milliliters of effluent. Most devices commonly installed on boats have a bacterial count much less than required, normally producing effluent with less than 10 coliform bacterial per 100 milliliter. This type of MSD must also not discharge any “visible floating solids.”

A Type II MSD must be certified to a level of a bacterial coliform count of not more than 200 per 100 milliliters, and total suspended solids of not more than 150 milligrams per liter. Few boats under 65 feet in length are equipped with this type.

A reminder: sewage, whether treated or not, cannot be discharged overboard in any designated “No Discharge Zone.”

Type III MSDs

Type III marine sanitation devices are described in the regulations as “non-flow-through” devices; there are two subcategories of this type.

Type III-A MSDs are designed to treat the sewage and hold it for later disposal. Typically, this is a RECIRCULATING TOILET that is “charged” with a few gallons of water and special chemicals. An example of a fixed model of this is the toilet used on passenger aircraft; boats usually use a portable model, such as a Porta-Potti, with this device being limited to smaller craft. The treated water, plus the waste, is recirculated each time the toilet is used. The toilet can normally be used for several days before pump-out is necessary. This type also includes reduced-flush devices that ultimately evaporate and incinerate the waste to a sterile sludge or ash.

Type III-B MSDs are collection, holding, and transfer systems consisting of drain piping, HOLDING TANKS, pumps, valves, connectors, and other equipment used to collect and hold shipboard sewage waste for subsequent transfer to a shore sewage system, sewage barge, or for discharge overboard in unrestricted waters. Holding tanks are the common form of MSD found on boats that are not fitted with a Type I device. Tanks may be rigid in various shapes or flexible; they should be sized to fit the size and use of the boat. An indicator and/or warning system can be used with a holding tank to alert the skipper to an impending need for pump-out. Chemicals can be added to reduce any offensive odors, but these do not qualify as disinfecting the waste. Obviously, holding tanks cannot be pumped overboard in any “No Discharge Zone.”

Combination Systems

An excellent solution to the boat sewage disposal problem is a combination of a Type I MSD followed by a holding tank, as in the Raritan Electro Scan system. This allows you to treat the waste before it goes to the holding tank, reducing the possibility of unpleasant odors, and still allowing you to pump overboard where such action is legal.

Other Required Equipment

Additional items of equipment required by law or Coast Guard regulations to be on board some or all boats include a whistle, a bell, navigation lights, and, in some instances, one or more day shapes. As with other equipment, these devices are graduated with the size of the vessel, and may vary with the waters on which they are used.

These requirements are covered in the Inland and International Navigation Rules; see Chapters 4 and 5.

Federal requirements for recreational boats are summarized in Table 3-3.

State & Local Requirements

Boaters may expect to have to comply with additional requirements in many states, and possibly additional ones in some local jurisdictions. These are too diverse to be covered in this book, but each skipper should be aware of the possible need for additional legally required equipment in both home waters and other cruising areas.

Table 3-3 In addition to the federal equipment carriage requirements for recreational craft summarized above, the owner/operator may be required to comply with additional regulations specific to the state or area in which the boat is operated.

Equipment for Commercial Craft

Boats (including sailing and nonself-propelled vessels) used for carrying six or fewer passengers for hire (paying passengers), or for commercial fishing, are “commercial uninspected vessels” subject to the Motorboat Act of 1940 and Coast Guard regulations issued under the authority of that act.

All nonrecreational craft less than 40 feet (12.2 m) in length and not carrying passengers for hire, such as commercial fishing boats, must have on board at least one life preserver, buoyant vest, or special-purpose water safety buoyant device of a suitable size for each person on board. “Suitable size” means that sufficient children’s lifesaving devices (medium or small, as appropriate) must be carried in addition to adult sizes.

All vessels carrying passengers for hire (six or fewer) and all other vessels subject to the MBA/40 and over 40 feet (12.2 m) in length must have at least one life preserver of a suitable size for each person on board.

Each vessel 26 feet (7.9 m) or more in length must also carry at least one life ring buoy in addition to the life preservers or other wearable lifesaving devices required.

All lifesaving equipment must be in serviceable condition; wearable devices must be readily accessible, and devices to be thrown must be immediately available.

More than Six Passengers

Vessels carrying more than six passengers for hire are subject to a separate act and set of Coast Guard regulations (see Chapter 2). These vessels must be “inspected” and certified as being equipped with the specified minimum equipment such as lifesaving gear and fire extinguishers.

ADDITIONAL EQUIPMENT FOR SAFETY

Any newcomer to boating might think that he would be fully set to go if he ordered his new craft with “all equipment required by federal and state regulations.” Actually, such is far from the real situation. Federal requirements stop too soon; state requirements—lacking uniformity—are not much help.

The list of items beyond federal requirements that you should have for safe boating is amazingly long. It is based on common sense and on the experience of many skippers over many years. Not every item will be required on every boat—the list must be tailored to your particular craft and boating activities—but you should at least consider each item discussed below.

Possible Liability

Another factor necessitating the carrying of equipment beyond the legal minimums is the possibility of LIABILITY in case of an accident. It is a mistake to think that the boating equipment specified by the government is the only equipment that you are legally bound to have aboard. Consider as well the far-reaching rules of NEGLIGENCE, as developed over the years in court cases. Technically, negligence is the unintentional breach of a legal duty to exercise a reasonable standard of care, thereby causing damage to someone. More simply stated, it is the failure to conduct oneself as a reasonable person would have under the circumstances. If, for example, a reasonable person would have carried charts, you may be liable to an injured party for an accident arising out of not having them available on board. If a reasonable person would have had an anchor, compass, lines, tools, and spare parts, etc., you may be held liable for not having them when needed. It is no defense to argue that no regulations require you to carry them.

Personal Flotation Devices Regulations set the minimum number and type of PFDs for your boat, but sound judgment often requires something better. Tests have shown that a Type II PFD may not keep your head sufficiently clear of the water in heavy seas—it’s better to have a Type I. If you ever expect to have multiple guests on board, make sure that you have enough for each person; if children might be involved, have several of the various sizes on your boat; see Figure 3-18.

Figure 3-18 Children do not float well in a face-up position and tend to panic easily. Type II PFDs are best for small children; an infant vest should have built-in rollover and head-support features.

The legal requirement is for one throwable device. You should consider whether one is enough, and maybe there should be one each of two or more different types, such as a buoyant cushion and a small life ring with a length of light line attached. This latter device can be used to either rescue a person in the water or to float a line over to a disabled boat that cannot be approached too closely because of shoal water, fire, or other emergency condition.

PFD Lights & Reflective Material

In order to better locate persons in the water at night, boats in commercial operation on certain waters must now carry personal flotation devices that are equipped with a light and reflective material—on both front and back sides—that will show up in the beam of a searchlight. Although such extras are not required for recreational boats, it’s a good idea for increased safety! Kits are available for adding reflective material to existing PFDs. A “water light” is a device that automatically comes on when it comes into contact with water; this makes a ring or horseshoe buoy much easier to locate at night; see Figure 3-19.

Figure 3-19 A water light is not legally required, but a light such as one that can be deployed with a horseshoe buoy will greatly increase the possibility of locating a person overboard at night.

A simple whistle attached to a PFD with a short cord is a valuable aid in nighttime rescues.

Life Rafts

Boaters who use colder northern waters or cruise more than a few miles offshore in any waters should consider the purchase of a life raft to supplement other lifesaving gear, though not required by the Coast Guard. Essential features include redundancy in buoyancy tubes, stowage on deck, gas cylinder inflation, water ballast or pockets, insulated floor, a canopy, boarding ladder and lifelines, a painter (to secure the raft to your boat so that it will not drift away), locator lights, adequate survival equipment and first-aid kit, a rainwater collector, a sea anchor or drogue, and an Emergency Position Indicating Radiobeacon (EPIRB). The raft should be able to accommodate the largest number of persons expected to be carried while offshore; more than one raft may be needed; see Figure 3-20.

Figure 3-20 Any skipper cruising offshore, especially in northern waters, should consider equipping his boat with a life raft. These are available in models for coastal cruising and distant voyaging. Life rafts must be maintained and periodically inspected in accordance with the manufacturer’s specifications.

It is important to note that life rafts are categorized by the waters on which they are intended to be used. Inshore rafts are little more than buoyant platforms that will permit survivors of a sinking vessel to get out of the water. Coastal rafts should only be used in waters where rescue can be reasonably expected in one day—typically within 20 miles (VHF radio range) from shore—as they lack features for extended use. Offshore rafts extend this period to four to five days—they have canopies and multiple buoyancy tubes. Rafts that meet the international requirements for ships (SOLAS—Safety of Life at Sea Convention) are the highest category—these rafts are designed for survival of up to 30 days and have the most support features. Some rafts are not Coast Guardapproved but may be suitable for limited boating activities; some are approved, but only for certain categories of vessels. Others have full approval.

A four-person life raft is one rated to support four adults while it is half-inflated. It does not necessarily provide comfortable space for four persons; SOLAS/USCG standards require only four square feet per person, and unapproved rafts may provide even less. On the other hand, a raft loaded to capacity may be more stable and will be warmer in cold weather.

Even with today’s advanced search and location techniques, your predicament and location may not be known to rescue authorities. The latest models of EPIRBs are excellent but not perfect. Weather may delay search and rescue for many hours. If you get into a life raft in an emergency, you should be prepared to spend an indeterminate time there.

Life rafts are cumbersome, expensive, and require costly annual inspections. But if you boat in any circumstances where a collision, fire, or sudden uncontrollable leak might place you and your crew in the water—away from other boats that might provide assistance, and drifting farther from shore—then you should have one. A life raft is not intended for use until an emergency occurs—but then it must work! It is of the utmost importance that life rafts are properly stowed and that they are serviced periodically at an authorized facility.

Lifelines, Safety Nets & Harnesses

Make sure everyone on board follows the traditional mariner’s advice: “One hand for yourself and one for the boat.” No matter how seasoned your sea legs, when the weather is rough, keep your center of gravity low as you move about the boat. Further ensure stability by grasping handholds.

Figure 3-21 Netting rigged along the lifelines of a sailboat is an excellent safeguard against children or pets falling overboard.

On sailboats, lifelines serve as boundaries for the deck, particularly when children or pets are aboard. Many people reinforce those boundaries by rigging nylon netting along the lifelines (see Figure 3-21) or between the hulls of catamarans or trimarans. When small children are adventurous, however, or when the boat is pitching, rolling, or heeling, safety harnesses provide additional safety insurance; see Figure 3-22.

Figure 3-22 A safety harness is added insurance against falls overboard, and enables you to know where your child is at all times on board a boat.

In addition to ensuring that you know a child’s whereabouts at all times, a safety harness is essential in other conditions for boaters of all ages. It will keep you aboard even if you fall, and should be worn anytime you are sailing alone, whenever any crew member is on deck in heavy weather, when going on deck alone at night while underway, when going aloft, or whenever you feel there is a danger that you might lose your footing.

Put on the safety harness before going on deck, and remember that a safety harness is only as strong as its attachment point. The best attachment point is a JACKLINE, or jackwire—a bow-to-stern trolley-like wire on a sailboat deck, onto which safety harness tethers are securely clipped. In the absence of a jackline, a harness should be hooked to the windward side of the boat—only onto a sturdy through-bolted fitting (a cleat, winch, or stay, for example); the mast; or stainless steel eyes of a toe rail or a grab rail. Keep in mind that lifelines and stanchions cannot be relied upon to withstand a great deal of force; therefore, they are unsuitable attachment points.

When shopping for safety harnesses, choose only models designed for use on board a boat, with reinforced nylon webbing, stainless steel hardware, and a tested strength of at least 3,000 pounds. The harness should fasten at the chest, with a catch that responds only to firm, positive action for release; the USCG recommends quick-release-under-load catches and buckles. A harness should have a stainless-steel snap hook at the end of a tether no longer than 6 feet. If you attach a sailing knife to the harness, in a sheath and with a lanyard, you will always have a tool handy.

Each safety harness aboard your boat should be adjusted to fit the person who will wear it, then labeled to ensure quick identification when needed in an emergency. Stow your harnesses in dry places and inspect them regularly for wear and tear, along with your other safety equipment.

DON’T FORGET A PFD FOR YOUR PET

Although probably the best action is to leave pet dogs and cats ashore, some skippers just can’t bring themselves to do that. If you have a pet on board, it should have its own life vest. This device will provide both additional flotation and a means of retrieval by hooking with a boat hook. The flotation device should be worn at all times when it is on board, including when your boat is docked. Even if your pet is a good swimmer, animals that jump or fall overboard often become confused and swim away from your boat rather than toward it; strong currents can carry a pet away from a boat that is anchored or on a mooring. In either of these situations, the life vest will keep your pet afloat until you can get to it. The PFD must be properly sized, and the animal must be gradually introduced to wearing it; a cat will probably be more resistant to wearing a life vest than a dog.

Fire Extinguishers

As with other required equipment, the regulations call for a very minimum of fire extinguishers; it would increase your safety if you carried additional units. If your boat is of the type or use category that does not require carriage of a fire extinguisher, you should consider carrying at least one unit, and two are not too many.

Extinguishers should be located around the boat where they will be close at hand if needed. One should be close to the helm and another in the galley. On many craft, it is desirable to have one in the engine compartment. It would add to the safety of your boat if an extinguisher were located close to the skipper’s bunk, where it could be grabbed quickly in the event of a nighttime emergency.

A fire extinguisher rated B-I by the Coast Guard can be as small as one that is rated 5-B:C by Underwriters Laboratories. The additional cost is minimal to upgrade to an extinguisher rated 10-B:C. Note that the Coast Guard requirement is for a B:C extinguisher—that is, one designed for fighting fires involving flammable liquids and usable on fires related to electrical circuits. As discussed earlier, there are also Class A fires, such as those that might occur in a trash basket, upholstery, or bedding. An even better extinguisher, one rated 1-A and 10-B:C, would add a capability to fight such fires of ordinary combustible material at only a slight increase in cost.

Navigation Lights

The builder of your boat was required by the Coast Guard to install navigation lights that meet the minimum requirements of the Navigation Rules; see Figure 3-23. But perhaps you would want your craft seen at a greater distance when out boating at night. Have you ever tried to find out from how far away your boat could be seen and recognized for the type of vessel that it is? You might be surprised, and not pleasantly, at the results of such a test.

Figure 3-23 Make sure your navigation lights fully meet the legal requirements, and then a bit more. Check that each can be seen through the required arc, and not beyond those limits. Check the lights on your boat from a distance, from shore or by going out on another boat.

On smaller boats, especially open craft of the runabout type, there is often a problem with the white forward or all-round light. It is often not high enough to be seen from ahead, being blocked by a top or even by the bodies of people on board. Make sure such a light on your boat is mounted high enough—or, if mounted on a collapsible post, that it can be raised high enough—to be seen from any direction.

Visual Distress Signals

If you meet the VDS requirement by carrying three hand-held flares, you are “legal” but hardly safe. Even if you are careful to wait until you feel sure there is someone within visible range, it is highly likely that you may use all your flares and still not be seen. Be safe: Carry more than the legal minimum of hand-held flares and consider having on board several red aerial flares that can be seen from a greater distance—or even better, red aerial parachute flares that will burn longer and be more likely to be seen than a meteor flare.

Lines & Anchors

Even the smallest rowboat or dinghy needs at least one length of line for making fast to a pier, mooring, or anchor, and a 40-footer (12.2 m) will need some six or eight dock lines—yet none are required by Coast Guard regulations. No sensible skipper would venture far from shore without an anchor—but again, none is required.

The number and length of dock lines will naturally vary with the size of the craft on which they are carried; see Chapter 6. A heaving line of light construction is desirable if your boat is large enough to need heavy mooring lines. The use of polypropylene line, or other material that is brightly colored and will float, is recommended for this purpose.

An anchor is a valuable safety item should the engine or steering fail and your boat be in danger of drifting or being blown into dangerous waters. Much more on anchors can be found in Chapter 9. All but the smallest craft should consider carrying more than one anchor.

Bilge Pumps

The list of required equipment does not include a bilge pump to get rid of water that comes in from rain, spray, or a leak in the hull. It has been said that there is no more effective “dewatering device” (to use a Coast Guard term) than a frightened boater with a bucket. Still, there is much safety achieved by having one or more electric bilge pumps, preferably backed up with an installed manual pump; see Figure 3-24. Bilge pump intakes should be fitted with a screen or filter to preclude any chance of becoming blocked by debris or loose objects in the bilge.

Figure 3-24 Electric bilge pumps are suitable for most boats, but have limited pumping capacity. The helm should have a panel light to indicate when the pump is running. Every boat with such pumps should have a manual pump of adequate size to provide additional pumping capability and to back up the electric pump in case of power failure.