Prologue

QUESTIONS AND THEIR PREDECESSORS

All Ages (as if Athens had been the Original) have been Curious in their Inquiries; … there is no laying it aside till the whole Frame is dissolved.”1

—MEMBER OF THE ATHENIAN SOCIETY (1703)

THE INTERROGATIVE is as old as language. “Questions” are an essential element of the Socratic method. In the late medieval and early modern period, scholastics had their “quætio(nes),” catechisms posed questions to offer scriptural answers, and the national academies that sprang up throughout Europe in the seventeenth and eithteenth centuries organized question competitions. But in the nineteenth century a new kind of question came into being, the shorthand for which might be given as “the x question.” Its proliferation was prodigious. Already in 1893 the Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy wrote with undisguised exasperation:

I constantly receive from all kinds of authors all kinds of pamphlets, and frequently books. [On]e has definitely settled the question of Christian gnoseology … a third has settled the social question, a fourth—the political question, a fifth—the Eastern question.2

Beyond the nameless querists who beleaguered Tolstoy, many of the most prominent figures of the time put their pens to questions. Alexis de Tocqueville took on the Eastern, sugar, and fiscal questions; Victor Hugo and George Sand both wrote poems on the social question.3 Karl Marx and Fyodor Dostoevsky addressed just about every major question; Frederick Douglass spoke passionately about the antislavery question; and the Czech philosopher and politician—and later first president of independent Czechoslovakia—Tomáš Masaryk wrote weighty tomes on the Czech and the social questions.4 Even Tolstoy himself weighed in on the Eastern question through the character of Levin in the last segment of Anna Karenina.5

And the trend continued. More-contemporary works range from treatments of “Disraeli and the Eastern Question” to “Freud’s Jewish Question” to the relationship between the Jewish and the woman questions.6 It is difficult to stifle an intellectual yawn upon hearing the phrase “the x question,” not because the formulation failed to elicit enthusiastic engagement but because there has been so much of it. Yet somehow we have not wondered: when and why did people start thinking in terms of “the x question,” and what did it mean?

Definitions

The chapters that follow speak to a particular type of rhetorical formulation that takes the form “the x question” rather than simply any context in which the word “question” appears. Obviously there were “questions” well before the nineteenth century, and there were even a few of the form described above, but the central object of the present analysis is the emergence and spread of “the x question,” which began in earnest in the 1830s, continued for more than a century, and has surfaced occasionally in public discussion and quite frequently in scholarship since.

Sharing a habitat in the nineteenth century and inspired by a set of historical catalysts that overlap with those that gave rise to “the x question” were the Russian “accursed questions” (What is to be done? Who is to blame? Whither Russia?7). Martin Heidegger’s Fragen (The Question Concerning Technology) after the essence of things or Elias Canetti’s “questioning” as “forcible intrusion” offer crooked-mirror reflections of the age, as well.8 In the chapters that follow, various connections will be explored between some of the above and “the x question.” Nonetheless, the reader should guard against conflating every nineteenth- and early twentieth-century appearance of the word “question” with the phenomenon here under scrutiny.9

Similarly, although the commodities and material questions, such as the corn, bullion, sugar, and oyster questions, share many common features with the great social and geopolitical questions of the time, the reader should not assume that all querists sought to forge a link between the tuberculosis question, for example, and the longed-for/feared “universal war.” The temptation will be to hold every treatment of every question up to the generalizations derived herein, whereas nearly every discrete treatment of every question will fail to live up to generalization in at least one, often in multiple respects. The object here is to glean whether any recurrent patterns can be perceived across the aggregate of “x questions” that appeared in the nineteenth century. It will be for the reader to decide whether it was a worthwhile endeavor to seek such patterns and whether the results of that endeavor warrant further consideration. Far from the definitive work on the subject, the present analysis is but a first foray, which will hopefully produce refinements and corrections as more scholars bring their expertise to bear on the subject.10

Finally, on the problem of establishing the origins of particular questions: The astute reader will note that many of the issues discussed under the aegis of a given question—the Jewish question, for example—were discussed well in advance of the actual formulation of the “Jewish question” as such in the 1820s. The matter of Jewish emancipation was raised prior to and during the French Revolution and became an essential feature of many treatments of the Jewish question later on. This is true of many other questions, as well (the Eastern, slavery, woman, Polish, social, etc., questions).

Yet what you have before you is an attempt at a history of the age of questions, as opposed to a comparative history of individual questions and their predecessors. The implications of this distinction are as follows: the present work does not trace the content of questions except insofar as their content overlaps significantly with that of other questions of the time. Where the historian of a single question might rightfully consider what issues came to characterize it, and the parameters of the study might therefore justifiably “overflow” its formulation as a question in the temporal sense, this study wonders instead whether there was such a thing as an age of questions; when and why it began; what commonalities can be observed in the way questions were framed and discussed; and to what extent those commonalities hold across all “types” of questions (social, (geo)political, material/economic, scholarly/professional), across national or linguistic contexts, across persons who weighed in on them, across the political spectrum, and over the long century that marked their heyday.

The scope of the project is both very broad—spanning as it does over two centuries and numerous national, imperial, and continental contexts—and also quite narrow. Its narrowness is evident in its methodology; to compensate for the megalomania of the temporal and geographical scope, it chooses to reveal patterns rather than to explain why they emerged in each given context. Party politics and the exigencies of the French Left’s, or the Russian Slavophiles’, or the German Romantics’ engagement with this or that question will be discussed very little or not at all. The reason is simple: because the emphasis is on commonalities across contexts, contextual particularities do not effectively account for why the Spanish and Czech literature should reproduce the same forms and tropes.

Yet context is still important. The chapters offer four loci of contextual particularity: the formal (by analyzing features that emerged within discussions of particular questions, such as the American, social, Jewish, Eastern, Polish, and nationality questions); the personal (with examples from individuals’ engagement with multiple questions or with the spirit of the age); the national (with a case study on the “age of questions” in Hungary, as well as some sub-studies on questions’ emergence in Britain and the forms they took in places like Russia, France, Germany, Austria, the United States, and Turkey); and the temporal (with a chapter on periodicity and pace in the way questions were discussed). Beyond these particularities, the reader will also find references to publicistic literature representing a variety of languages and contexts (French, Spanish, Russian, Polish, German, Italian, English, Romanian, Hungarian, Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian [BCS], Slovene, Slovak, Czech, Bulgarian, Macedonian, and Turkish), as well as archival sources from Austria, Bulgaria, Britain, Hungary, Germany, Turkey, Serbia, Romania, the United States, Slovakia, and Croatia.

The Reality of Questions

Historians have generally assumed there is a real essence to questions that can be historicized; that the woman question is about the emancipation of women, the social question about gross inequality, the Jewish question about the status of Jews in largely Christian societies and states, and the Eastern question about how to manage the decline of the Ottoman Empire. There is some truth in such general assessments, but it is also true that one essential feature of questions is that they have been chronically, indeed almost reflexively redefined.11 Since the framing of a question was understood to determine its solution—a phenomenon I will discuss at greater length below—and since offering a definitive and therefore unique solution was the ultimate intervention, reframing or redefining a question was of first-order importance to the serious querist.

Whereas the German theologian Bruno Bauer wrote of the Jewish question that it was “just one part of the great and general question for which our time works on a solution,” Karl Marx offered a “critique” of Bauer’s Jewish question as a means of solving it; Walter Scott saw it as a component of the Eastern question that would be solved by Christ with the “personal reign of the Messiah,” and Theodor Herzl defined it as a “national” question, one essentially about territory.12 In other words, to borrow a phrase from Fyodor Dostoevsky writing on the Eastern question, “everyone conceives it in his own way, and no one understands the other.”13

The same has been true of the Polish question, the cause of much reflection and lobbying, and the subject of a massive body of literature that generally assumes everyone knows, or at least should know, what is at issue with the words “the Polish question” (the irony of redefinition was that a new way of seeing a question also had to appear self-evident). Adding to the confusion is the development of a secondary literature about the Polish question, but wherein the author of a monograph or an article, rather than the individuals writing on the Polish question during the period under consideration, determines what is meant by the “Polish question.”14 Hence we find works—such as the 1905 book by a Russian scholar, Mikhail Petrovich Dragomanov, on Herzen, Bakunin, Chernyshevsky and the Polish Question—wherein those authors made few if any direct references to the “Polish question.”15

A historian might wonder who lived in Poland, what those inhabitants’ claims to national independence were, what their role in Europe was or should have been, what outsiders projected about Poland’s future. But to suggest that the “Polish question” and its “solution” are identical to such considerations is to ignore the very obvious if somehow hitherto obscure fact: the Polish question, like others of the time, was like an arrow-shaped signpost, pointing to a particular querist’s preferred “solution.” There were certainly commonalities of content across a number of interventions on the Polish question, but if we probe only those commonalities—particular historical interpretations, claims or counterclaims to independence, heroes and villains—we lose sight of what bound the Polish question to other questions of the time and what the ramifications of thinking in questions were.

Beyond Begriff

The present study shares with conceptual history (Begriffsgeschichte) an interest in origins and changes in meaning over time. Furthermore, questions emerged squarely in the period (1750–1850) Reinhart Koselleck designated as a “saddle-period” (Sattelzeit), or period of transition wherein concepts emerged that were both abstract as well as future oriented, so studying them may serve to further establish the significance of that time.16 Nonetheless, this is not a conceptual history, nor does the story follow the plotline laid out by Koselleck.17

That Koselleck and his coauthors did not view nineteenth-century questions as “concepts” is evident from their Basic Concepts in History, in which certain questions do appear but are taken to describe what the authors considered to be actual historical and political phenomena rather than concepts.18 The present analysis does not place questions below the level of concepts—as Koselleck did—but rather above them, in that it shows how they were both changeable in accordance with historical events and conditions as well as connected to one another through the word question, which had its own implied trajectories and constraints. As such, the analysis owes more to Michel Foucault than to Reinhart Koselleck, although admittedly more to an unwitting slip of Foucault than to his ideas about language and structures. In the introduction to his famous essay “What Is Enlightenment?,” taking Immanuel Kant’s earlier essay by the same title under analysis, Foucault wrote,

Today when a periodical asks its readers a question, it does so in order to collect opinions on some subject about which everyone has an opinion already; there is not much likelihood of learning anything new. In the eighteenth century, editors preferred to question the public on problems that did not yet have solutions. I don’t know whether or not that practice was more effective; it was unquestionably more entertaining.19

He was referring to the eighteenth-century prize competitions run by national academies: academicians would formulate a question and anyone could submit an answer. The best answers were rewarded with publication and distinction (viz. Kant’s answer to the question “What is Enlightenment?”). Although Foucault was not alluding to the emergence of nineteenth-century “x questions,” the passage demonstrates how thinking in questions is a most peculiar kind of thought that effortlessly spans an abyss between two meanings. In the first part of the passage, Foucault speaks of questions requiring opinions, whereas in the second, of problems to be solved. The leap is considerable, and when even someone as sensitive to the subtleties of language makes it without reflection, its naturalness seems doubly affirmed. The history of the “age of questions” begins by wondering: what made this leap feel so natural?

Questions as Problems

The etymology of question in several languages reaches back to Latin, and the Latin back to Greek.20 In those languages, as well as in the word’s twelfth-century Middle French and Anglo-Norman incarnations, its meaning encompassed both “query, inquiry” as well as “problem or topic which is under discussion or which must be investigated.”21 These two meanings cohabitate in the words for “question” in French, German, Russian, and most other European languages.22 There are some telling exceptions, however, which point either to the deep roots of the combined problem/question meanings (Greek) or themselves reveal the imprint left by the age of questions on modern languages (such as Romanian and Polish).

In Greek, the word used for nineteenth-century questions is ζήτημα (issue, matter) rather than ερώτηση (question), but the word ζήτημα also encompasses the meaning of “(object of) inquiry,” from ζητέω, meaning “to inquire” or “to investigate.”23 Furthermore, ζήτημα is a synonym of πρόβλημα (problem), ερώτημα (question), and θέμα (subject, issue, matter, topic).24 In Ancient Greek, the words ζητεύω and ζητίω were the equivalent of the Latin quæro, and ζήτημα was the equivalent of the Latin quæstio.25

The Polish word sprawa, the most commonly used translation of question—in the sense of “x question”—early on, is not identical to the word question in English because it means only “affair,” “problem,” or “matter.”26 Yet there is another word that came to be used later in Polish, namely, kwestia or kwestya, which is related directly to the Latin, French, and English words for “question” and shares their dual meaning insofar as it is a verbatim import from the Latin/French. This fact suggests that the word was endowed with its primary meaning in Polish during and because of the age of questions, for whereas in most languages the word for “question,” with its slippage between “question-to-be-answered” and “problem-to-be-solved,” is translatable and translated, this is only partially true in others, such as Polish, Spanish, and Romanian.

In these languages, the most common words for “question-to-be-answered” are pytanie in Polish, pregunta in Spanish, and întrebare in Romanian, whereas the words kwestia or kwestya (Polish), 27 cuestión (Spanish), and chestiune or chestie (Romanian) have been broadly used to refer to “x questions.” In the case of Polish and Romanian, at least, these variants were likely imported from the French with the meaning of “issue,” “problem,” or “matter” precisely to accommodate the emergence of “x questions” in the nineteenth century. The definition of chestiune from a 1939 Romanian etymological dictionary thus included the following elucidation: “A question posed to clarify an issue. A proposal to examine, subject to discuss, matter/affair: Eastern Question.”28

Certainly many before and since Foucault have propagated the conflation of question with problem.29 Bruno Bauer’s 1843 “Die Judenfrage” (The Jewish question) is generally translated as “The Jewish Problem,”30 and Karl Marx, in his reflections on the Polish question as in the context of the 1848 Frankfurt Assembly, made the same substitution in the course of a single sentence: “As it is closely connected to the Polish question, the Poznan question could only be resolved if merged with the entirety of this problem.”31 An article from 1877 by the American journalist Edwin Godkin calls the Eastern question “the oldest existing problem in European politics”; and shortly after the end of the Great War, John A. Ryan, a priest and professor at Catholic University in Washington, DC, and one of his students, Reverend Raymond McGowan, published A Catechism of the Social Question. It begins:

QUESTION: What do we mean by the social question?

ANSWER: A question denotes a problem or a difficulty which demands solution.32

More recently, scholars writing on questions have continued the tradition of conflating “question” and “problem.” The English translator of Dostoevsky’s Diary of a Writer regularly swapped out the Russian writer’s вопросы (questions) for the English problems.33 Charles and Barbara Jelavich defined the Eastern question as “[t]he problem of the decline of Turkey and the diplomatic complications which ensued.”34 The late Ottomanist Donald Quataert summarized it as “how to solve the problem posed by the continuing territorial erosion of the Ottoman empire,” and the historian L. Carl Brown called it “that very modern problem.”35

Ennui and Excess

Part of the challenge of undertaking a history of “the age of questions” is that questions appear to exist within an untidy zone between historical phenomenon, period Begriff, and historiographical framework. Authors writing about questions in the nineteenth century speak of them as though they are real and clearly defined problems, but in doing so they are also actively seeking to cast them as problems to an audience they hope to excite and influence. Then come the historians, who have taken these period authors’ books, articles, and pamphlets on a subject such as the Eastern question and made assumptions of their own about what the “real” question is or was, dropped in their own definitions, chronologies, and histories of a question, sometimes at the same time that questions were a regular feature in newspapers, pamphlets, and parliamentary proceedings.

Furthermore, because the Eastern question, the worker question, the Polish question, the Jewish question, et cetera, were the dominant preoccupations of entire fields of scholarship and political activism for decades, if not for over a century, reference to them invariably produces an involuntary historiographical ennui. In his epic history of Poland, God’s Playground: 1795 to the Present, the historian Norman Davies wrote,

For 150 years, the Polish Question was a conundrum that could not be solved, a circle that could never be squared. In that time, it generated mountains of archival material and oceans of secondary literature. For the historian of Poland, however, the Polish Question is a singularly barren subject.36

Davies’ passage reveals how the sense of urgency, indeed emergency and feverish agitation that pervades much of the nineteenth-century writing on questions has a peculiar counterpoint: scholarly ennui. This work means to leave behind both urgency and ennui, which exude a smug knowing, in favor of simple curiosity, and to ask questions about questions to which we do not already have the answers.

Predecessors and Foils of Questions

Where did the questions of the nineteenth century come from? There are traces of many forms in them, from almanacs to debating societies and legal proceedings. Yet while “the x question” acquired traits from these ancestors, querists also defined their questions against the earlier scholastic questions and sought to make way for a new and above all timely form.

Scholastic and Practical Questions

The scholastic question, or quaestio disputata, played an outsized if largely invisible role in the age of questions. The quaestio was a method of argumentation based on Aristotelian rhetoric commonly used in the medieval universities from the twelfth to the seventeenth centuries. Figures such as Thomas Aquinas and William of Ockham used the method to teach science and medicine.37 But most of the quaestiones were theological and philosophical, possessed of an expansive timelessness that was not easily reconciled with practical, earthly matters. (One other root of the word question is the Old English cwestion, as in “theological problem.”38) Aquinas, for example, wondered about the existence of God, the origin of evil, and whether hope is a virtue.39

Meanwhile, medieval and early modern mystics wielded questions to suggest a realm beyond human knowledge. In 1620, the German philosopher and theosophist Jakob Böhme wrote his True Psychology: Explained through Forty Questions.40 The questions were put to him by a Doctor Balthasar Walter, and pertained to everything from the essence of the soul to the involvement of the dead in the lives of the living. In the introductory comments preceding his replies, Böhme wrote that “it is not possible for Reason to answer to your Questions: for they are the greatest Mysteries, which are alone known to God … You shall be answered with a very firm and deep Answer … not according to outward Reason, but according to the Spirit of Knowledge.”41 The author demurred in the face of divine wisdom: only God knows, but sometimes God reveals his mysteries in unlikely ways, and the question and answer form could be one of them. Revelation—either through reason or through the “Spirit”—were the aim of both the quaestio disputata and the mystics’ project.

Despite the deep etymological roots of the “question,” it was not always or consistently the case that, as problems, they had to be “solved” rather than “answered.” The scholastic questions discussed by figures like Aquinas and Ockham, as well as the catechisms that became popular during the Reformation, had questions and answers.42 Yet with scholasticism in decline in the seventeenth century, questions were becoming more practical and timely than spiritual and timeless: they begged not an answer but a resolution or solution.

The linking of questions to solutions is apparent in English in the sixteenth century, and by the seventeenth was being more rigorously applied to “practical” questions.43 In 1661, the English mathematician Noah Bridges published his Lux Mercatoria, offering “a more easie and exact Method for resolving the most Practical and Useful Questions than has been yet published.” Bridges’s “questions” included “the most Critical Questions of Reduction, Trucks, and Exchanges of Monies, Weights and Measures of Foreign Countries.” The semantics of Bridges’s work—which was republished in numerous editions over the coming decades—was that of questions to be “resolved” and the method was mathematical.

In effect, the Lux Mercatoria was a work of applied mathematics, wherein a number of challenging “questions” were “resolved at one operation.”44 Practice “questions” for the reader were referred to as “useful and pleasant questions to exercise and improve the Learner,” with “answers” also given.45 The exercises appeared after a section on “division,” in which Bridges laid out the method of “proof” for a correct operation of division. The “proof” consisted of working backward from the solution. If the solution was correct, it would yield the original terms.46 (Example: if you divide twelve by three, you can check your answer [4] by multiplying it by three to get twelve). You could derive a solution based on the rules of mathematical manipulation, and you could derive the terms from the solution.

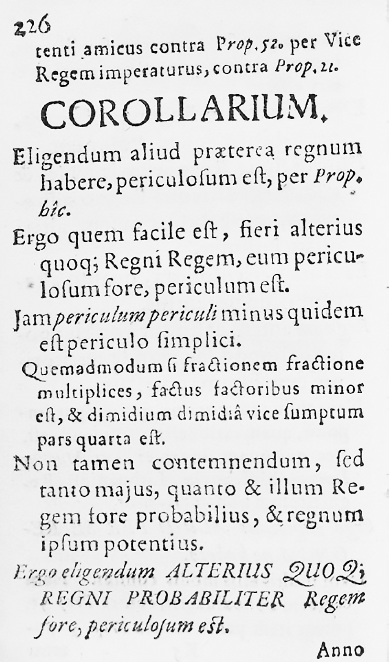

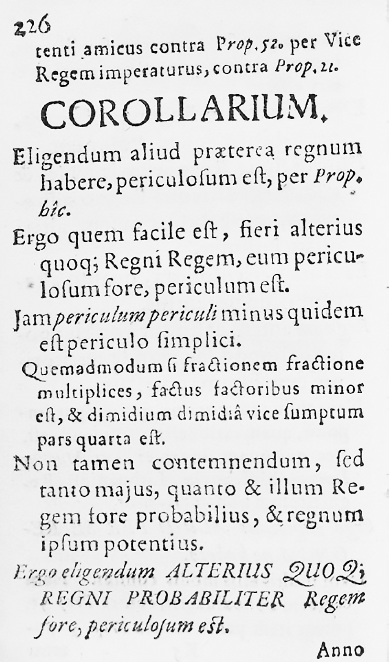

In 1699, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), destined to become the first president of the Prussian academy, wrote a pamphlet arguing for the election of Pfalzgraf Phillipp Wilhelm von Neuburg to the Polish throne. The pamphlet was written at the behest of his patron, the baron Johann Christian von Boineburg, “in the form of a mathematical demonstration which was supposed to convince the electors on the basis of clearly stated, stringent reasons for favouring Boineburg’s preferred candidate.”47 In so doing, Leibniz was among those who opened the path to conceptualizing contemporary political and social issues as problems requiring mathematical-type solutions, and for which only one solution can be correct. The “practical” turn evident in the Lux Mercatoria and Leibniz’s “proof” foreshadowed a characteristic of nineteenth-century questions that contrasted sharply with the timelessness of scholastic questions.

Nowhere is the contrast more clearly spelled out than in the debates surrounding the bullion question in Britain during the first two decades of the nineteenth century, relating to how Britain should materially back its currency in light of the expenditures of the Napoleonic Wars. By 1816, the regular treatment of the bullion question in the periodical press and pamphlets brought the English poet and historian Robert Southey to disparage the question, as well as the related corn and population questions as “the fleeting fashion of the day.”48

The same temper of mind, which in old times spent itself upon scholastic questions, and at a later age in commentaries upon the Scriptures, has in these days taken the direction of metaphysical or statistic philosophy. Bear witness, Bullion and Corn Laws! Bear witness, the New Science of Population! And the whole host of productions to which these happy topics have given birth, from the humble magazine essay, up to the bold octavo, and more ambitious quarto.49

Southey feared that the great scholastic questions were being supplanted by practical and timely ones. In the introduction to his Principles of Political Economy—written in 1819—the English scholar Thomas Robert Malthus responded to Southey’s dismissal of the new questions, mounting a spirited defense of the new political economy as a “practical” science, “applicable to the common business of human life.”

FIGURE 1. Page from Leibniz’s Specimen Demonstrationum Politicarum, which he organized as a series of propositions and corollaries, building upon one another in the manner of a mathematical proof. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Specimen Demonstrationum Politicarum Pro Eligendo Rege Polonorum, Novo scribendi genere ad claram certitudinem exactum [An essay on political demonstrations for choosing a king of Poland, completed in a new style of writing for exact certitude] (Vilnius, 1669), p. 226.

I cannot agree with a writer in one of our most popular critical journals, who considers the subjects of population, bullion, and corn laws in the same light as the scholastic questions of the middle ages, and puts marks of admiration to them expressive of his utter astonishment that such perishable stuff should engage any portion of the public attention … The study of the laws of nature is, in all its branches, interesting … but the laws which regulate the movements of human society have an infinitely stronger claim to our attention, both because they relate to objects about which we are daily and hourly conversant, and because their effects are continually modified by human interference.50

Timeless and universal questions were not to be the stuff of the nineteenth century; “the x question” was self-consciously of its time.

Querelle, querist, querulant

The scholastic quaestio disputata was—as its name suggests—a form of dispute, a pedagogical conceit of the medieval university crafted to buttress learning through argumentation and repetition. Appropriately then, one of the oldest questions was not a question at all but an argument, the so-called querelle des femmes as it was formulated in France in the sixteenth century.51 The expression would eventually morph into the question des femmes, or woman question. It is noteworthy that the term querelle (dispute) should give way to question if we consider how period authors understood the semantics of questions.

In querelle, the largely outdated word querist (questioner) overlaps in meaning and application with the “querulant” (malcontent, troublemaker); the word querist in historical usage was often preceded by negative-connotative adjectives such as impertinent, insatiable, troublesome.52 Over the nineteenth century the “querulant” also became a psychiatric and legal designation for a paranoid person who obsessively feels wronged or driven to litigate.53

During the reign of “the x question,” the querulous roots of questions were well in evidence. In addition to being synonymous with “problems,” questions were also often synonymous with disputes requiring (or resisting) arbitration or mediation.54 In a poem from 1831, the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin referred to the Polish question as “a dispute between the Slavs / A domestic, age-old argument, too laden with fate / A question that is not for you [Europeans] to solve.”55 And of the Central American question between Britain and the United States in 1856, the US secretary of state, William L. Marcy, wrote to his British counterpart:

In a controversy like the present, … the matter should be referred to some one or more of those eminent men of science who do honour to the intellect of Europe and America, and who, with previous consent of their respective Governments, might well undertake the task of determining such a question, to the acceptance as well of Her Majesty’s Government as of the United States.56

Nineteenth-century literary questions—such as the Hamlet, Shakespeare, Homeric, Madách, Toldi, and Ady questions—were scholarly disputes; around whether Hamlet’s “to be or not to be” was about suicide or the thought-barrier to meaningful action, whether Shakespeare/Homer/Madách truly wrote the works attributed to them, whether the character Toldi in the nineteenth-century poetic trilogy by János Arany was based on a real historical figure, or whether the leftist poet Endre Ady was a saint or a devil.57 Such literary disputes carried the mark of the earlier “Querelle des Anciens et des Modernes” (quarrel of the ancients and the moderns) that unfolded in the French Academy in the last decade of the seventeenth century and spread from there to Britain and beyond, a quarrel over whether modern knowledge and culture could ever truly outstrip that of the ancients.58 Some nineteenth-century questions were also designated “querelle,” including the German question, occasionally referred to as la querelle d’allemands.”59

Catechism

Beginning in the 1710s, the “querist” appeared as a malcontent in several publications on theological matters in Britain.60 These interventions speak to another of the likely ancestors of questions, namely, the catechism. As noted above, the Old English cwestion meant “theological problem.”61 More pertinent to this analysis is the popular pedagogical role that the catechism played in disseminating religious doctrine, a function outlined by Martin Luther in his “Preface” to the 1529 Small Catechism. “Therefore I bid you all for God’s sake, my dear lords and brothers, who are pastors or preachers, … to help us bring the Catechism unto the people, and especially unto the young.”62

In 1742, the Unity of the (Moravian) Brethren published a “manual of doctrine” in English that included some telling reflections on the chosen form. Questions were put by the author, Nicolaus Ludwig Graf von Zinzendorf, with “answers” drawn from scripture. Zinzendorf explained the format: “We have reduced them into Questions. For we do not seek for Texts suitable to our Thoughts, but take our Thoughts from the Texts we read … This is our Methodus sentiendi. Way of Thinking.”63 The author denied asking questions to prove a point but appealed instead to the authority of scripture. In a subsequent introduction, Zinzendorf observed that some questions “were not always well enough adapted”:

[T]he Reason why they were so as they are, to be the great Attention I had to the Texts of Scripture; for the Questions arose to me from the Texts of Scripture, and … I hastened to make short Questions between them, just to give the whole some Connexion … This Reason seemed of Weight; and I feared running into the common Fault, where the Texts are looked out for the Question’s Sake; and it made me choose rather to leave my Labour unpolished, that the Holy divine Scripture might retain its native Splendor and Emphasis, and every Reader’s Eyes might immediately fall upon the Texts.64

Questions, Zinzendorf insisted, came after and were secondary to the scripture. Yet by flagging the “common Fault,” he admitted that it would always be tempting to start with a conclusion and work backward to the question, and ultimately who could tell if the querist was serving God’s or his own ends? The quandary is one the age of questions inherited and could never fully resolve.

Furthermore, framing scripture as an “answer,” hardly a novelty in the Judeo-Christian theological universe informed by Talmudic contemplation, necessitated the fashioning of a question. The author worked backward from the answer. In this way, the catechistic questions affected the realm of the thinkable by conditioning readers and listeners to expect an authoritative and definitive (which is to say, scriptural) answer. And catechisms were generally published in the vernacular, so laypeople could understand them and, ideally, also study them on their own. The revelatory and popular pedagogical character of many nineteenth-century interventions on questions is therefore at least partially traceable to the catechism.

Finally, it is perhaps also significant that Zinzendorf spared no criticism in passages regarding teachers among the ranks of men: “What do they chiefly amuse themselves with?” The answer from 1 Timothy: “Doting about Questions and Strifes of Words.”65 Here we recognize the malcontent, the querist as querulant, and a tension between the pedagogical thrust of the catechism (the text) and the manipulative rhetorical skill of the teacher (the person).66 Later questions would carry unmistakable traces of this tension with authoritative texts (laws, treaties, etc.) as constant referents, often pitted against the skill of pamphleteers, politicians, and orators. Some queristic interventions would even assume the catechistic form explicitly.67 The revival of religious catechistic works in the nineteenth century seems a significant conjuncture, as well, given the sprawl of catechistic thinking.68

Pamphlet to Palladium

The catechistic function of establishing what one ought or ought not do had a corollary in a body of seminal publications framed in a similar vein.69 In mid-seventeenth-century Britain, publications began to appear on a variety of themes referring to the “grand” or “great” question. In 1643, an anonymous author published a short pamphlet titled The Grand question concerning taking up armes against the King answered by application of the Holy Scriptures to the conscience of every subject.70 Several other “grand” and “great” questions appeared over the coming decades, all of which set out to inform and influence the opinion of readers on a given issue.71

Among them were two pamphlets by Daniel Defoe (the author of Robinson Crusoe), each addressing “Two Great Questions.” The first, from 1700, was on “What the French King will Do, with Respct to the Spanish Monarchy” and “What Measures the English ought to take.” The publication elicited two written replies, to which Defoe responded. In 1707, he published a second pamphlet on “What is the obligation of Parliaments to the addresses or petitions of the people” and “Whether the obligation of the Covenant or other national engagements, is concern’d in the Treaty of Union?”72 In both publications, Defoe laid out the terms of the discussion as questions, which duly implied the necessity of taking a particular action. Similarly, Montesquieu’s 1748 The Spirit of the Laws, included a chapter on the “applications” of the text’s ideas laid out in the form of questions (i.e., “It is a question, whether the laws ought to oblige a subject to accept of a public employment.”) to which the author provided his own proscriptive answer (yes, in a republic, no, in a monarchy) based on the “general principles” outlined in the text.73

Another likely forerunner of later questions was the periodical the Athenian Mercury—out of which was compiled the Athenian Oracle, the British Apollo, and later the Palladium—featuring a querist as problem- or riddle-maker, or a reader submitting a question to an anonymous “Informer” (who assumed the identity of the god Apollo). In these works, “querist” was a neutral and largely descriptive designation, as in the later Reverend George Berkeley, Lord Bishop of Cloyne’s The Querist: Containing Several Queries, Proposed to the Consideration of the Public, which first appeared in 1735.74

The history of the Athenian Mercury dates back to 1691, when a London publicist founded the Athenian Society of scholars, whose members answered questions submitted by readers to a popular periodical by that title.75 Beginning in 1703, the Athenian Society of London published The Athenian Oracle Being an Entire Collection of All the Valuable Questions and Answers in the Old Athenian Mercuries. In its first run, the Oracle explained its raison d’être as follows:

The Design is briefly, To satisfy all ingenious and curious Enquirers into Speculations, Divine, Moral, and Natural, &c. and to remove those Difficulties and Dissatisfactions, that shame, or fear of appearing ridiculous by asking Questions, may cause several Persons to labour under, who now have opportunities of being resolv’d in any Question, without knowing their Informer.76

Like the catechism, the anonymity of the “Informer”—and the conflation thereof with the god Apollo, just as the query format self-consciously imitated the oracle at Delphi—implied authoritativeness and engaged in a form of popular pedagogy (an advice column avant la lettre). The questions in the Oracle covered a considerable range: “Whether it was a real Apple our Parents did eat in Paradice?” (in a manner of speaking, an apple, or perhaps a fig); “Where and when were Dials, Clocks and Watches first made?” (ancient Egypt); “Whether it is better to live single, or to marry?” (probably to marry); “Whether every Angel makes a Species?” (it depends).77

The British Apollo: Containing Two Thousand Answers to Curious Questions In Most Arts And Sciences, Serious, Comical, And Humorous, Approved of by Many of the Most Learned And Ingenious of Both Universities, And of the Royal-Society first appeared in 1726, and was based on a similar premise. It included questions submitted by readers—some mathematical, others inquiring whether to marry a maid or a chandler’s daughter—all answered by “Apollo.”78 The first Palladium appeared in 1752. Collectively, these publications advanced by degrees the equation of social and other concerns with mathematical problems or puzzles. Starting with the second edition, the questions (queries) were submitted by readers, and the answers/solutions were offered by someone with a pseudonym, implying that there was a different specialist answering each one.79

“That the World is a Riddle has long been agreed, / Who solves it an Oedipus must be indeed!” Such is the introductory verse to the The Gentleman and Lady’s Palladium For the Year of our Lord 1753. The verse opened a volume featuring “new ænigmas, queries and questions” on a range of topics spanning from the causes of sodomy to “[w]hether we are influenced to esteem and respect men for their Riches and Rank they bear in the World, more than for their innate Worth and Merit.” These followed a section of riddles (or “ænigmas”) and were posed to the “Royal Oracle” or “Querist,” along with “questions” that amounted to mathematical problems (puzzles) submitted by readers. Among the questions put to the oracle the year prior and answered in the 1753 issue were how to prevent robberies in London (“by mending the Morals of the Common People”), whether general naturalization is desirable (yes and no), and whether women should be allowed to wear breeches (no).80

FIGURE 2. The British Apollo: Containing Two Thousand Answers to Curious Questions in Most Arts and Sciences, Serious, Comical, and Humorous,

Approved of by Many of the Most Learned and Ingenious of Both Universities, and of the Royal-Society, 3rd ed. (London: Printed for T. Sanders, 1726).

Debating Societies and Prize Competitions

The Palladium opened a venue in the public sphere similar to the one created by the London debating societies, a forum wherein literate individuals could discuss social, economic, and sometimes even political issues of the day. It was at these societies that the likes of Edmund Burke and William Pitt honed their oratorical skills. Debates were generally advertised as “rational entertainment” in the press, and as many as 650 people of various classes might attend a weekly session. In advance of the session, a question was chosen as the topic of debate, and a debate ended when the audience voted on a winner, sometimes only after several sessions in which any paying member could at least theoretically participate.81

In the sources relating to these societies, we find some traits they had in common with the later “x question.” A pamphlet dating from 1753, titled The Other Side of the Question. Being a collection of what hath appeared in Defence of the late Act, in Favour of the Jews, claimed that

[a] calm and impartial review of the nature and tendency of the inflammatory libels, which have been of late so industriously circulated through the nation, will enable us to discern, that it is the design of their authors to divert the attention of the public from the true state of the question; and by exciting disturbance in the nation, to accomplish the political schemes of some leading craftsmen in the ensuing elections.82

The promise to offer a “calm and impartial” intervention into a heated and overcrowded rhetorical field on a given “question” then before national government was to become a signature feature of the age.83

An article in a British daily newspaper from 1788, reporting on the topic of discussion at the Westminster Forum, suggests a link between the activity of the debating societies and the emergence of the later “(anti-)slavery question.” “This Evening,” we read on the cover of the Morning Post and Daily Advertiser of London from March 10, 1788, “the following adjourned Question will be debated: ‘Can any political or commercial advantages justify a free people in continuing the Slave Trade?’ ” The article ended with the notice: “Gentlemen are particularly requested to attend, in order that they may hear the arguments on both sides, and their decision be the result of a fair and free Debate.”84 Though the debating societies were largely unique to Britain, it would not have been uncommon for a gentleman visitor to England from France to attend one or more of these debates—which took place several times a week—as they were a noteworthy spectacle of the time.85

A more geographically widespread venue in which questions were raised and discussed and “solutions” proposed during the eighteenth century were the prize competitions of national academies, which Foucault alluded to in his essay “What Is Enlightenment?”86 These academies were founded mostly in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (in London in 1660, Paris in 1699, Berlin in 1700, Petersburg in 1724, Prague in 1785, Budapest in 1825, Vienna in 184787), and several of them held prize competitions on questions ranging from electricity and winches to using observations to determine the time, “natural inclinations,” and “parental authority.”88 These competitions offered a forum for written interventions prompted by a theme or question. Many of the winning entries were published as pamphlets, a common format for the querists of later decades.

Official Venues

Finally, it is essential to note that official settings also lent their forms to the “age of questions.” The terms querelle, querist, and querulant, for example, all bear relation to the language of legal procedure, and especially the trial, for much of the argumentation around questions drew on the language of trials and other legal proceedings: proving with evidence (facts and precedents), standing before courts, juries, judges, and the like.

An early pamphlet on the (Roman) Catholic question dating from 1805 speaks of bringing it before “a Tribunal and a Public” for due consideration.89 “It will be for the public to judge,” the anonymous author of an 1826 pamphlet on the West India question concluded, “whether [the statements and reasonings which appear to belong to a practical consideration of the West India Question] are not sanctioned by common sense and by the experience of history, and above all, whether they are not reconcilable with the true and genuine spirit of the Resolutions of the House of Commons.”90 An early treatment of the Polish question is tellingly titled The Polish Question before the Court of the Sword and of Politics in the Year 1830.91 And in a book from 1863, a Polish nobleman from Russian Poland similarly addressed the “great court known as ‘public opinion,’ ” and noted the status of the “question polonaise” as a “cause célèbre … with public opinion as jury and Europe as judge.”92

But by far the most directly traceable origins of the nineteenth century’s “x questions” were the proceedings of representative assemblies (above all, the British Parliament), treaty negotiations, and the official correspondence surrounding them. That story belongs to the age of questions itself, however, and thus to the arguments that follow.