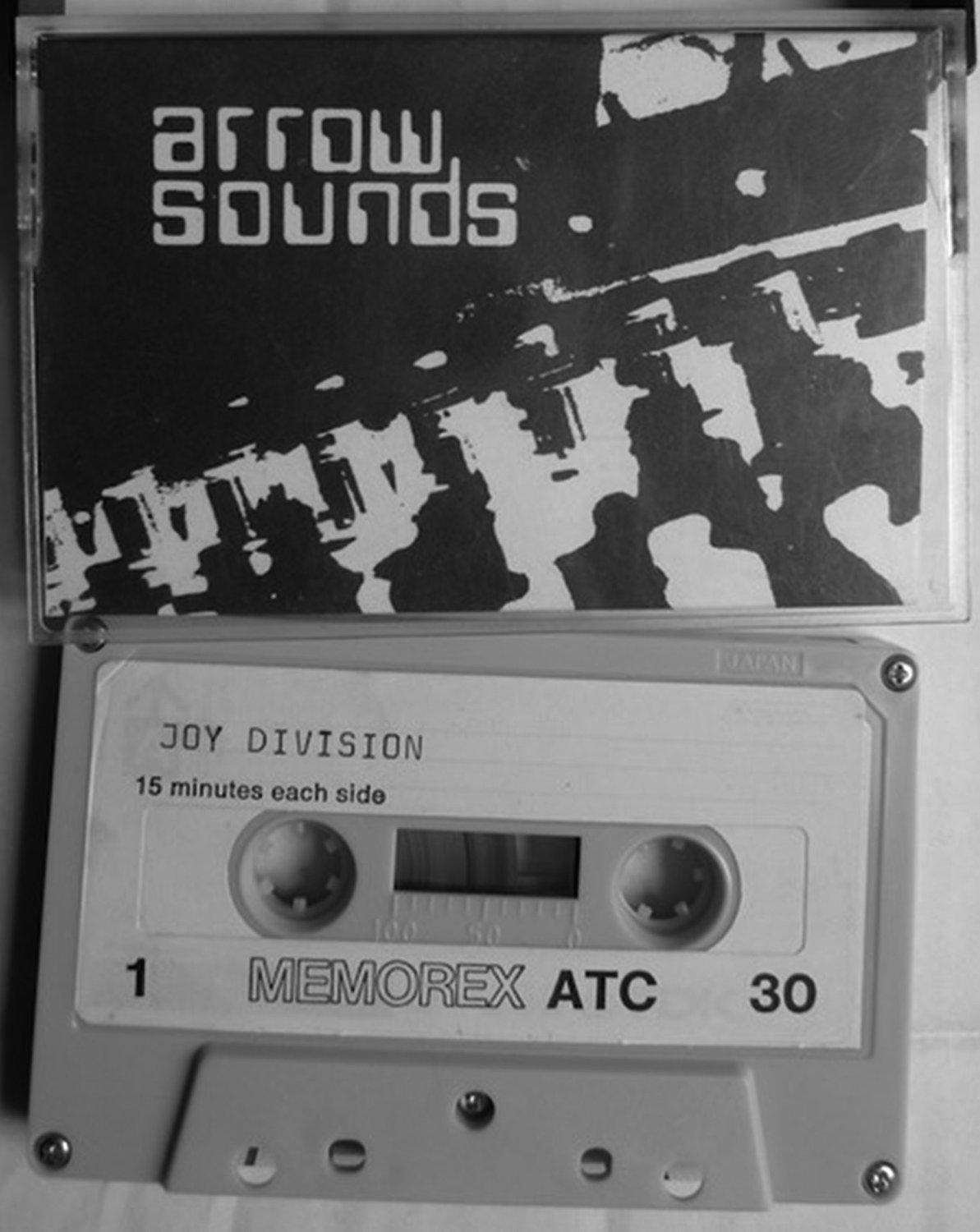

Cassette, Joy Division RCA album, summer 1978 (Courtesy of Jon Savage)

Bernard Sumner: The next day I remember being in a phone booth in Spring Gardens in Manchester, just outside the post office. There was a knock on the booth. I opened the door and went, ‘Yeah?’ It was Rob Gretton. ‘Are you out of that band Joy Division?’ I went, ‘Yeah.’ He said, ‘Well, I’m the DJ at that club, I’m Rob Gretton, and I’ve actually been sacked from my job. I work in the day for an insurance company, but I’ve been sacked for being too bolshie. I’m on my way now to get a temporary job cleaning toilets in the Arndale Centre, but I’d rather be your manager.’

So I was like, ‘All right, yeah, what do you want to do?’ He said, ‘Can I come to one of your rehearsals and we’ll have a meeting about it?’ I said, ‘We’re rehearsing like next Sunday or next Wednesday, come along.’ It was in this old factory that we used to rehearse in. I forgot all about it, so I didn’t tell anyone. We’re rehearsing and Rob walks in the rehearsal room, so we just carry on, and he sits down and everyone’s like, ‘Who’s that? Who’s that?’ And then we stop. ‘Who are you?’

He was really embarrassed, and I went, ‘Oh, I forgot to tell you, this guy wants to be our manager.’ Rob was a bit paranoid because everyone seemed to be unfriendly to him, so he said, ‘All right, let’s go to the pub and have a meeting about it.’ We went to the pub, but in those days you didn’t buy a round of drinks, you just bought yourself one. We all used to go to the bar: ‘I’ll have a sweet martini please, Hooky’ll have a brown ale.’ Steve would have a Coke and Ian would have a Special Brew, but we’ d all buy our own drinks. Rob was just sat there without a drink.

By this time he’s completely paranoid that he’d been set up by the band, that we were taking the piss out of him, but we weren’t. That was just the way we did things. But the meeting went really well and we desperately needed a manager, so Rob got the job. He seemed to have some good ideas, and he was the missing link that we needed to move forward. He was pretty punk in the way he thought. When he was DJing he was playing soul music, but his ideology was really punk.

- 3 and 4 May 1978: RCA sessions, Arrow Studios, Manchester

Stephen Morris: The RCA record was before us bumping into Rob. Ian was hanging about Piccadilly Gardens, where RCA at that time had an office in Manchester, and cos Iggy and Bowie were on RCA and I think he just thought maybe Bowie would turn up one day to see how many records he’ d sold. He got talking to Richard Searling and Derek Bramwood: this was another side of Ian that I’ d never seen before, this schmoozing side where he was kind of, ‘Oh yes, I’m friends with Derek at RCA.’

Richard Searling had this friend of his in King’s Lynn who was starting a punk-rock label. He’d done a northern soul label called Grapevine, which had some sort of connection with RCA. We got roped in as being the token punk-rock band and ended up making an album at Arrow Studios, just off Deansgate. It was an interesting experience. It was all a bit of a cock-up, we shouldn’t have done it, but someone comes up to you and says, ‘Hey, guys, here’s a contract, you can make an LP,’ again, it’s like you’re climbing up that ladder, and so we went and did it.

Bernard Sumner: We’ d met a guy called Richard Searling from RCA Records. RCA weren’t interested in us, but there was a record that came out in the seventies by the Floaters called ‘Float On’. It’s that one: ‘Hi, my name’ s Larry, I’m Capricorn,’ and then the whole band introduced themselves and their star signs. Classic record. It was corny as shit but it was massive. And this guy was the guy that put that record together, and he thought punk was the next big thing and wanted to record an album with us. He was going to put the money up. I think he worked for TK Records, and he wanted us to do a cover version of this northern soul record called ‘Keep on Keeping on’, which when he played it I was quite impressed by, it had a really stonking guitar riff. We thought, ‘That’s a pretty good record. We know Richard Searling from RCA, he’s a decent guy, so we’ll do it.’

Richard Searling: Ian was a regular visitor to the RCA offices. The main reason for that was that he adored Iggy Pop. Derek looked upon him almost as a son. Ian was a shy guy, unassuming, but somebody that would keep coming back, as a lot of people did, because the office was a central point. It was very close to Piccadilly Radio, Derek had got it positioned perfectly. I think CBS was the only other label at the time that was in Manchester, so Derek pushed very hard to get that office against a lot of political resistance in London.

At the time we were running Grapevine Records, run by John Anderson in King’s Lynn, whom I’d helped get a deal through RCA, and we had a splendid launch in London. Northern soul really was that big, you were going to sell some copies. I remember on the same week that we did the Joy Division sessions – the sales used to come through on a Tuesday – we’ d sold thirty-eight thousand of a record by Judy Street called ‘What’, which is a classic. For some reason it didn’t chart, because in those days if it was regionalised, they’ d just pull it.

John Anderson’s partner in America was a guy called Bernie Binnick, who was a bit of a legend. He’d owned Swan Records in Philadelphia and signed the Beatles there. Bernie had a connection with Henry Stone, who ran TK, who were really hot, with people like George McCrae and Jimmy ‘Bo’ Horne, and they wanted a punk band. I didn’t know anybody other than … ‘Oh, Ian’s got a band.’ They’d just been up at Pennine, they’d done a thousand copies of an EP. I seem to remember him showing me a shrink-wrapped copy and saying, ‘We’ve got 999 left.’ They’d just changed their name to Joy Division.

Manchester was awash with bands at the time, and nobody could have predicted that they would be where they ended up being. But Bernie wanted to get a band, and it seemed worth having a go. I can’t remember exactly how we did it. I do remember that it took a little bit of convincing, because none of us knew what the hell we were doing. Somehow we managed to cobble together about £1,400, and off we went at £35 an hour into Greendale Studios.

We did the sessions, with a little bit of John Anderson saying, ‘You need to use a synthesizer,’ which they didn’t want to do. We laid the tracks down remarkably quickly. I think the engineer must have been pretty good. I was there, but it was John and the engineer that were doing the work. I seem to remember playing pool upstairs most of the time. The tracks sounded fantastic. By the Wednesday we hadn’t got the vocals down in any way, shape or form. I think we tried to loosen Ian up with cider, which I seem to remember he liked drinking, but only to get his vocals right.

On the Wednesday night I can distinctly remember John saying to me, ‘We’re not going to complete these sessions, these vocals aren’t really right. Can you get Paul Young in from Sad Café?’ Which is absolutely abhorrent, isn’t it? But if you think about it, we’d got till Thursday night to get it finished. But it all came together, it came together so well that when we played people the cassettes, they were absolutely astonished. Even RCA sat up and took notice, and that’s when the rot started to set in, because the band didn’t want to be within RCA. That was the last thing they wanted.

Bernard Sumner: So we went in the studio with this guy. He wanted to cut an album with us in two days – a day to record it and a day to mix it – and the guy was a pain in the arse, he was not on our wavelength at all. We went into central Manchester, we recorded this album in a day. My guitar amp was playing up. It was a fifty-quid amp and it was buzzing and farting and the speaker cone was damaged, and he was pulling his hair out: ‘Look, you’ve only got a day. Time’s money, we’re running out of time. You fix your amp, get some Sellotape or something.’ The whole thing was a shambles.

Just as we were leaving, he said, ‘Right, we should have done the vocals today, but we’re going to have to do them all tomorrow morning before we start mixing.’ He said, ‘What you want to do is get a load of James Brown records, play them tonight, learn how James sings, and sing like James tomorrow morning.’ Ian just went, ‘Let’s just fuck it off now.’ And we were like, ‘What? Fucking first opportunity of being in a studio?’ We had a bit of an argument, and Ian was going, ‘This guy’s a knobhead, we should just fuck off.’ But we turned up, and Ian didn’t bother singing like James Brown.

I remember us sat there in the morning in a really bad mood, and they’d double-booked the session in the morning with a guy that was singing an advertising jingle, and he kept singing this jingle for Littlewoods Lotteries: ‘Littlewoods, Lotteries, more and more win Littlewoods, Littlewoods, Lotteries, more and more win Littlewoods,’ in a phoney American accent. We were in the worst mood, and the guy would go, ‘Right, you’ve lost another hour, get in and do your vocals.’ Like, an hour to do all the vocals. And then we started mixing, and it just turned out dreadful.

Stephen Morris: I can always remember him trying to get Ian to sound like James Brown, and the best way to get Ian to sing like James Brown was to get him absolutely paralytic. Apparently, James Brown did the same thing, so we just got a bottle of whisky and were plying him with whisky and telling him to belt it out like James Brown. It’s not the way really; he just got kind of very fractious and started yelping like a dog. Anyway, it was a learning experience, the RCA record – it’s not the way to do it – so that when we did do Unknown Pleasures, we knew what to do.

What we did get out of it on the plus side was – this might have been hedging their bets a bit: ‘If it doesn’t work as a punk record, we can probably salvage it as some sort of northern soul/punk crossover.’ – ‘Why don’t you do a cover of N. F. Porter’s “Keep on Keeping on”?’ Which was the first of our many ill-fated cover versions, because every time we try and cover something, it ends up being something else, and in this case it ended up being ‘Interzone’. It was their idea to cover it, so we did, but we did it a bit differently. I mean, N. F. Porter’s ‘Keep on Keeping on’, it’s a great song anyway.

Richard Searling: N. F. Porter’s is a really powerful record. As the insistent, urgent lyrics would tell you, it’s a black man’s plea to his fellow man not to give up: ‘Keep on, don’t let the system get you down.’ It wasn’t a typical northern soul record actually, it was probably more or less a new release – it only came out in 1971. The suggestion of ‘Keep on Keeping on’ came from my wife, Judith. I think we must all have had very fertile minds in those days about how we saw this session going at Greendale. The band didn’t have any resistance to that. I think they probably raised their eyebrows a little bit. As I said, there were varying degrees of cooperation. Ian was very positive. Steve was quite a nervous guy, didn’t really say too much. Bernard was quite suspicious, which, as he was a businessman, an old head on young shoulders at the time, I think he would have thought, ‘What the hell are we doing with these guys?’ They worked at that, and to give the band their due, having heard the track they got on with it and did a fantastic track. I don’t know what they ended up calling it, but it was great.

So ‘Keep on Keeping on’ was done. There was a track called ‘They Walked in Line’ as well on there, and that was funny because there’s a pub opposite Greendale and we took them for a drink, and my wife was there, and they wanted lager, and I went and got the drinks and got back, and they wanted lime as well, and Judith said, ‘They wanted lime, they wanted lime,’ and we sort of sang the thing. We gave them the opportunity when nobody else would, and I hope they look back on it as a positive week.

- June 1978: release of Ideal for Living EP on Enigma Records

- 12 June 1978: release of Short Circuit: Live at the Electric Circus, featuring Joy Division, ‘At a Later Date’

Peter Hook: That last night at the Circus album was a complete farce. It was a real stitch-up. The contract was the funniest thing I’ve ever seen: ‘All groups shall receive 5 per cent off Virgin.’ We thought that meant we got 5 per cent each, and what it meant was, we got half a per cent. Ten groups between them got 5 per cent, and Virgin got 95. Then, six months later, it was out with the big sticker: ‘Including Joy Division!’

Paul Morley, NME, 3 June 1978

Joy Division were once Warsaw, a punk group with literary pretensions. They’re a dry, doomy group who depend promisingly on the possibilities of repetition, sudden stripping away, with deceptive dynamics, whilst they use sound in a more orthodox hard rock manner than, say, either The Fall or Magazine. They have an ambiguous appeal, and with patience they could develop strongly and make some testing, worthwhile metallic music.

Alan Lewis, review of Ideal for Living in Sounds, 24 July 1978

Another Fascism for Fun and Profit mob, judging by the Hitler Youth imagery and Germanic typography on the sleeve. But interesting, and definitely worth investigating if you’re gripped by the grinding riff gloom and industrial bleakness of the Wire/Subway Sect Order.

Jon Savage, review of Short Circuit: Live at the Electric Circus in Sounds, 24 July 1978

Joy Division (then Warsaw) run through ‘At a Later Date’ which, like their EP ‘Ideal for Living’ hints at a promise yet to be fulfilled.

Bernard Sumner: We got the vinyl, Ideal for Living. I’d drawn the sleeve. ‘I know what we’ll do, take it to Pips, the local club that we go to, we’ll play it.’ By that time they had a punk room, so we went to the DJ and it was like, ‘Play our record, it’s us, just play that record.’ So he said, ‘No, fuck off.’ – ‘No, no, we’ve been coming here for years. Play it.’ He said, ‘All right, give it here.’

There were loads of people on the dance floor. He put it on, and the pressing was so bad it was completely muffled, so quiet that you wouldn’t believe it, and it just cleared the dance floor. Everyone just walked off, and he took it off halfway through. It was like, ‘Oh shit, what have we done?’ I blamed it on the pressing, but it could have been the music actually. It didn’t go down very well at all.

Peter Hook: It was a simple matter of physics really. If you put that much time on a seven-inch record, it’s going to sound shite. I know now that the monitors in the studio were distorting and that made it sound better, but when you put it on a record it didn’t sound anything like the studio. It was probably one of the most disappointing moments of my life: getting that record, taking it home and playing it, because it sounded so bad I wanted to die. All that effort and work, and all the hopes and everything you’d put on it, and it was just terrible.

Stephen Morris: Then we’re stuck with all these records. ‘What are we going to do? Oh God.’ I tried selling them. I actually did sell quite a lot – more than ten anyway – in the public houses around Macclesfield, so some people in Macclesfield must have a copy of Ideal for Living somewhere.

Mark Reeder: When they released the EP, no one wanted to stock it. I thought it was brilliant, I loved it. I knew Ian was interested in history, especially the Second World War and Germany. And since I’d been to Germany, he wanted to know all about it. I tried to explain to him, ‘It’s not like you imagine it to be, people goose-stepping around everywhere.’ That’s how people imagined Germany to be, just full of Nazis. But to have that on the front cover, I thought it was quite brave really. And when you opened it out, you had the Warsaw ghetto child inside.

Trying to sell the record, it was just at that pivotal moment, wasn’t it? You had Siouxsie on TV wearing a swastika armband – that definitely sent out the wrong signals to everybody. They worried about people thinking they were fascists and all the right-wingers suddenly coming out of the woodwork. It was sending out all the wrong signals. And the pseudo-Germanic lettering and doing songs like ‘They Walked in Line’ – I knew it fascinated Ian, the mythology and the occultism, because we’d talked about all that when we were teenagers.

Deborah Curtis: Ian was intrigued. I think he liked all the pomp and the uniforms and the strutting around. He thought Margaret Thatcher was fantastic. He liked to have his own way, to be in control, and it worked. He flattened me, to some extent, not that he was trying to flatten me, but he knew he could easily get his own way with me. I don’t think he could have married someone who was bossy.

You couldn’t have an argument with him about anything, because he’d just back down. He’d stick to his beliefs, but he wouldn’t upset anybody. Like this Nazi thing. He wouldn’t discuss it with me. I think that was because he knew we didn’t think along the same lines, so rather than have an argument – he didn’t like confrontation – he’d just keep quiet.

Paul Morley: Warsaw shouting ‘Remember Rudolf Hess’ at the Electric Circus and all that kind of nonsense: at the time, whenever any of that happened those of us within it had not a moment’s doubt that it was anything dicey; you just trusted somehow the instincts of locals that it was not. It could have been dangerous, but you just felt that it was them looking for some kind of dangerous energy rather than being actually fascinated in a sleazy, disastrous way. It just seemed clumsy rather than terrible.

Bernard Sumner: The Second World War left a big impression on me, via my grandparents. So the sleeve was that impression. It wasn’t pro-Nazi, quite the contrary. I just thought that people shouldn’t forget. As I was growing up, I felt that I was being taught by other people, my teachers, how to act and how to relate to the world. The generation before had gone through a period when the whole civilised Western world had gone through a world war. People had behaved in a completely insane way, killing each other.

One of the first things that Rob Gretton did when he came along was to say, ‘That fucking record you’ve done, get rid of that fucking cover. Everyone thinks you’re Nazis because of it. Whose idea was that, you tossers?’ So he said, ‘We’re going to do a new cover and we’re going to press it as a twelve-inch so it sounds loud.’ Rob was a DJ at that stage. So he did it and we played it, and he was right, it sounds fantastic, it sounds really good.

Another of the things Rob did, which was really good, was to raise two grand to buy the RCA tapes and the contract off this guy – we’d signed a bloody contract. Two grand was an enormous amount of money then, don’t know where he got it from. And we got the tapes, but of course it ended up coming out anyway as a bootleg after Joy Division became well known. It suddenly appeared, this crap album. So Rob gave us a togetherness.

Richard Searling: I remember them saying, ‘We’re bringing a manager in, any objection?’ I said, ‘No, you need one, you should always have had one.’ It was Rob Gretton. He needs all the tracks remixing, which was a bit of a shock to us, because we hadn’t really got any more money to do that. We felt it was good enough. I can’t remember who made the offer or whether we said, ‘Well, we need to get our money back.’ John thinks we got £700 back. I’m sure we didn’t, I’m sure we got all our money back.

All RCA were bloody bothered about was pushing a guy called Gerard Kenny. He was going to be the new Elton John. They weren’t really interested about some band in Manchester that could have made bloody millions if they’d treated it right at the time. God, Iggy Pop could have produced them, thinking about it. But I think at the time if you’d said, ‘Do you think the band are going to make it or not, Richard?’ I would have said, with everything else that was going on, ‘No, I don’t actually.’

Rob Gretton (as ‘Rob’, from Manchester Rains fanzine): This is a Slaughter and Dogs fanzine – it’s called ‘Manchester Rains’ because we’ve heard that London’s Burning (hooray!). We’ve decided to devote it to the Dogs because we feel that too many poxy bands, particularly from ‘The Big Smoke’ – it’s called that because it’s burning, see? – are getting a lot of exposure that they don’t really deserve.

Lesley Gilbert: We’d been to Israel on kibbutz for about six months, and we came back just after the Pistols played the Free Trade Hall, so we missed that, and obviously neither of us had a job when we came back. I got one pretty quickly, but Rob didn’t, so he had a lot of time on his hands. When Slaughter and the Dogs were starting up in Wythenshawe, which was where he was from, he knew somebody who knew them, and we went to see them one night and that’s what started it really. I’m not too sure why, but it really excited him, much more than it did me.

I was interested, but there was something that grabbed Rob. I think he just felt it was very exciting, and it came at a time in his life when he was really open to something completely new and completely different. I don’t think he was consciously wanting to change his life, but this really got him excited. He worked with them for a while, and then their manager, who was the brother of Mike Rossi, Slaughter’s guitarist, had to step down for a while, so then Rob took over managing them with Vinnie Faal.

We saw Joy Division together for the first time at the Stiff/Chiswick band thing, and they were on really late. We stayed to watch them, and they were just amazing. Their presence and the atmosphere they brought. I mean, after standing for a few hours and watching band after band after band, you would have thought, ‘Oh God, it’s the last one, thank God for that.’ But their presence was … I can’t describe it any other way, it was just, ‘Wow, these are amazing.’ Maybe not so much at that time the music, but it was purely a feeling.

Bernard Sumner: We needed a manager badly, and Rob was great. He wasn’t a businessman, and he could be belligerent and he’d treat us all like his children sometimes. I think he might have been a bit older than us. I think he felt me and Hooky were a bunch of thick tossers from Salford, cos he’s from Wythenshawe, and apparently people in Wythenshawe look down on people from Salford. Rob was a City fan. Everyone in Salford are Manchester United fans, everyone in Wythenshawe are Manchester City fans, so there was a bit of that, even though we weren’t that bothered about football.

He just thought we were a pair of Salford tossers. I remember the first time we stayed in a hotel together: ‘Excuse me, sir, would you like an alarm call?’ – ‘No.’ – ‘Would you like a newspaper?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ And he said, ‘Which one?’ I said, ‘I’ll have News of the World please.’ I remember Rob going, ‘[snorts] News of the World? You thick Salford bastard.’ Of course, he had the Guardian. And I was like, ‘What’s wrong with it? What’s wrong with the News of the World?’ I know now, but he thought that was just so typical, and that summed up what he thought of us.

But he was a good laugh and he was very into the punk ethos and doing things that way and not being mainstream, which suited us down to a T. I think if we’d been left to our own devices, we would have signed to anyone just to get our records out, but the fact that we ended up on Factory was really Rob stirring. Ian thought it was a good idea as well. Me and Hooky weren’t that bothered, but it gave us a great deal of creative living space.

Terry Mason: Barney had put in the least amount of effort of anyone. Me and Ian had gone down to London to try and get into record companies, we’d mail stuff off. We were the people who believed in the dream as such, that there’s something big there, and Barney was going along just as he felt. Rob turned up, and I think Ian was really upset by the way it was done, because he was a very honourable man. That didn’t seem right by Ian.

As a manager, I didn’t have a phone, which makes life a little difficult. Rob didn’t actually own a phone at that point, but the flat where he lived had a payphone outside his front door, so that was that. It was a weird situation: I’d gone from one of the founders of the band, put so much effort in, and then Rob comes in just as the first major hurdle had been cleared and I’m out on my ear. I was pissed off at that happening and I put out an injunction, not that I knew what an injunction was, but I knew it’s what people did.

There was never anything in writing, and things in writing with bands don’t mean anything anyway. But then I was left with the decision: do I give up everything – give up my mates basically – do I spit the dummy out, or do I stay with them? It was a fun hobby. Anyone who’s thinking about being in a band, no matter how awful, try it. It’s good, it’s fun, it doesn’t have to be for life, but try it for a while. I stayed with the band.

I had a meeting with Rob. He still wanted me around. I was still useful: I didn’t mind humping equipment up and down stairs, I was a driver, I was quite sensible about doing things. Then Rob said, ‘Well, what you can do is, the band can’t afford to bring in a sound engineer, you can learn.’ And from that point basically it was me doing that. You’re still very much part of it; these people were my friends, you don’t write off a bunch of friends over something like that.

Stephen Morris: Rob did make a difference. I think the fact that we’ d got a manager was a step up on the road, because we’ d done the record, we’ d done the gigs, and now we’ d got a manager, and it was like these are essential building blocks to the big time, and we’ d just got another one. Rob made us … I was going to say take it more seriously, but I don’t think we ever took what we were doing that seriously. We were passionate about it, but not to the extent where we were very, very serious about it. We were doing it because we enjoyed doing it. It was from the heart.

Terry Mason: There was this phase where, although we were the most unpopular band in town, it didn’t stop the band rehearsing and getting better. More of Ian’s songs were coming through. Some of the early songs were Hooky songs, and then all of a sudden Ian’s writing comes through, and it’s a different league. Everyone else in the country’s doing simple rhymes, and Ian’s putting these poems together, not that we could usually hear or understand what they were.

Bernard Sumner: I can’t remember exactly how it happened. We’ d just pick our instruments up and play. We’ d have some kind of crappy cassette recorder. Ian would usually go, ‘Oh, that bit’s good,’ because obviously we were concentrating, he was listening to it all the time. So I’ d go, ‘Oh, you like that bit, right?’ So I’ d probably arrange it. ‘How about going to here?’ And then we’ d jam on that, and ‘Okay, we’ll use that for the verse and we’ll use that for the chorus.’ It was quite simple really, but I guess because we didn’t know what we were doing, we ended up doing things in an unusual way.

You’d search for something that was easier to play on the guitar, and so you’d just go, ‘Right, try these two strings. Oh, that sounds good, I’ll just use that.’ My amp was so incredibly loud: to get any distortion out of it I had to have it incredibly loud or else it sounded awful. I used a strange amp that I found: I think it’s called a Vox U30. It’s not the Beatles Vox and it’s not an AC30; it’s a weird hybrid of a transistor amp and a valve amp, and it’s got a really biting, loud, angry tone to it, and I just love that amp.

I like to feel that I’ve got a good inherent sense of rhythm, so I’m quite a strong rhythm player. Because of punk and the thousand-notes-a-minute thing, I always thought it would be great if you’re doing a guitar solo, it was a better solo if you could play it with just one finger. It’s easier for people to understand what you’re getting at, so I always try to keep it simple. Hooky couldn’t hear himself play low down, so he started playing high up, so it was just a happy accident like that that gave us our sound.

I’m a pretty laid-back person, I’m not hyper by any means, and to play punk you have to be hyper or aggressive or mad, so it didn’t really work out. Then I developed my own style, which was slow and considered. I liked sound, and I used to play on the neck of the guitar where it sounded really nice. I’m more rhythm and chords, and Hooky was melody. He’s got a really good talent for melody. He’s got this powerful, barbaric part of his personality that people like, a strident quality that comes out in the music.

The strange thing is that we never used to talk about it, you just did it. A very unconscious way of writing music. There was no method that we used. We just used to wait for the inspiration. Ian was pretty good at riff spotting. He’d go, ‘Oh, that bit’s good, that bit’s good.’ And I’d go, ‘Right, okay, let’s play that bit round and round, right?’ And I’d suggest, ‘What if we went here to this?’ Everyone would try that, going to this place, and then someone else would come up with another idea, so then we’d end up with a track, and he’d play it on the cassette.

Ian would take it home, where he had a big box of lyrics. I can’t remember if he used to mumble any melodies on the tracks or not. I’ve got a feeling he did it all at home and he’d come back next rehearsal and we’d have finished lyrics. He used to sit at home writing anyway, that was his thing. He was a writer. He would always have a file box with him, full of lyrics. He’d sit at home and just write all the time, instead of watching telly, he’d stay up – I don’t know this, I’m surmising, because he’d come in with reams and reams of lyrics.

We talked about other people’s music: ‘Have you heard Iggy’s new record, “China Girl”? Let’s do something like that.’ But we couldn’t because we weren’t good enough. ‘Have you heard this track by Love, “7 and 7 Is”? Put that on.’ We’d go, ‘Yeah, do something like that,’ then we wouldn’t talk, we’d just do our thing. We wouldn’t go, ‘Yeah, it needs a middle eight,’ or anything like that. We just wouldn’t talk about it, you just didn’t. Sometimes for days nothing would happen, but some days we’d get some great ideas.

It would just happen, cos we didn’t know how to do it, we didn’t have any craft or skill, so it was a very naive form of writing. We just did what we thought sounded good, with the simplest of methods and the simplest of chords and the simplest of music. We thought the rhythm was very important, so we would always make sure that we had a good rhythm out of Steve before we’d start on the guitars. We’d sit around like, ‘Come on, Steve, give us some drum riffs.’ And we’d all sit around listening to drum riffs and go, ‘Right, that one. Okay, we’ll jam to that riff.’

Tony Wilson: It was all four of them, without any question. People talk about drummers being important to groups, and there’s no Joy Division without Stephen driving it that way and Bernard’s slash guitar, and clearly the core melodic element is Hooky’s high-fret playing of that bass, which no one had done before then. All of them had something to say, and they’d all been freed by the Pistols. And I don’t understand why that should glue together, that amalgam of those four people – it wasn’t just Ian, it was all four of them.

Stephen Morris: I started off doing kind of punk drumming. I didn’t really know what punk drumming was. I thought it’d be something like Maureen Tucker out of the Velvet Underground. The drummers that I was listening to were John French out of the Magic Band and Jaki Liebezeit out of Can. I tried to be what would happen if John French lived in Germany for a long time and listened to a lot of Krautrock. I wanted to do something different.

Maureen Tucker’s style of drumming was one of the things that you noticed about the Velvet Underground. It’s very, very minimalistic and quite dark. I liked that aspect of it, I liked drums being kind of hypnotic in a way – in the way that some of the Velvet Underground is – and that you could set some sort of a background and then put other stuff on top of it. I just wanted to play tom-tom things: I don’t know why, I was making it up as I was going along.

There were arguments. I mean, everybody argues, but we were almost a democracy. You were influenced by your limitations. We all depended on each other, and if you took one of us away, then it would stop sounding like Joy Division. It was just all of us together. Hooky couldn’t tune his bass, Bernard had to tune the bass and the guitar, and things like that, we did depend on each other quite a lot. I locked in with Hooky because he was trying to play melodic rhythms, and Bernard was filling in, he didn’t really do big guitar riffs, what he did was not intricate but textural.

Peter Hook: It’s funny, as a musician I always felt quite inadequate because I used to watch people slap and play reggae bass and think, ‘Oh, I can’t do that.’ I can’t play along to people’s tunes, I find it impossible. Like my mum used to say, I couldn’t carry a tune in a bucket. I think I’m partially tone deaf, so I can’t play other people’s music, so it used to really frustrate me, and it always seems to be the things you want are more important than the things you’ve got. I suppose in my mind or subconsciously I wanted to be like Jean-Jacques Burnel or Paul Simonon.

We used to rehearse twice a week, for three hours on Wednesday night and for two hours on Sunday, and in that time you’d invariably get a song. You had no way of recording it because we couldn’t afford a tape recorder, so the songs only existed in your head. It’s an amazing thought these days to think that Unknown Pleasures for the most part only existed in your head, and it only existed when the four of you played it together. It was mind-blowing to me that if one of us had died, it would have just gone. It’s absolutely bizarre.

I bought a bass capo off an old teacher in my school who played bass with the Salford Jets, Diccon Hubbard, and I couldn’t hear it when I played low, cos of the row, cos Barney’s amp was really loud. When I played high I could pick it out. Ian just latched onto you playing high, and he’d say, ‘That sounds good when you play high, we should work on that, that sounds really distinctive.’ And I’d go, ‘All right, which bit?’ And he’d go, ‘That bit you just played there.’ And all those songs – ‘She’s Lost Control’, ‘Insight’, ‘Twenty Four Hours’, ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’ – 99 per cent of the time started with the music.

Terry Mason: Very early on the band realised that they needed a tape recorder. They’d basically jam along, and from that they would pull out snippets, and as they were going along Ian would pull out one index card, have a go at those lyrics, see if they fit. It’s like an eye test – ‘Is it better with these lyrics? Is it better with these?’ – and they’d work it out that way. Because they had a tape, they could always go back and pick out what they’d done. At one point the band were churning out songs. They’d be working on bits and they had a lot of work in progress, and Ian would go back, rework it, throw something out, try something new; if they weren’t happy, leave it for a while.

Stephen Morris: You couldn’t tell what the hell Ian was going on about, because it was Ian’s PA. I had no idea what on earth he was singing.

Bernard Sumner: It was great because Ian could come up with the words just like that on top of what we’d jammed, so you’d end up with a song in a day. Once we got the initial riffs, then it was more up to me, Hooky and Steve to work on the arrangements, and he’d step out a little bit while we made it into a fully arranged song. Then he’d come in with the vocals. We were not bouncing off each other; we just completely ignored each other, we were all on our own island, and we just made sure that what we were doing sounded great, and we didn’t pay any attention to what the others were doing, not consciously anyway.

Obviously, subconsciously there were moments, but we didn’t talk to each other about it and just did our own thing. We didn’t know what we were doing, but something happened. We just knew we liked music. If you really love listening to music and it moves you passionately, like you hear a song and you play it over and over again and you absolutely love that song, to write music you just reverse that process: you feel a passion inside you, and then you get the passion to come out through your hands and through your minds.

I’ve also got to try and imagine what I’m going to play before I play it. I try to hear it in my head first and then try and translate it to my hands, and then it’s just a reversal of that really. We were all really into music: Hooky was, Steve had an enormous record collection, probably bigger than anyone, and Ian obviously did. But Ian was the writer of words as well. He was very into books, very bookish. I think if he’d have lived, eventually he would have become a writer. I think that would have happened quite soon actually.

Peter Hook: I suppose I’m more aggressive than Bernard, and a damn sight more aggressive than Steve, God bless him. Steve’s not aggressive at all, apart from when he does go, and when he goes he goes like a volcano, fucking hell. What I liked about Joy Division was that it was very equal: it was the four of us and you were all going in the right direction. Joy Division was balanced perfectly, which made it perfect.