- 5 June 1979: release of Unknown Pleasures

Bernard Sumner: I remember me and Hooky being a bit frustrated at the sound of Unknown Pleasures, because we felt that the sound of the group playing live was a lot wilder and more rocky and aggressive than the sound that came out on the album. If you’ve got any live recordings, you can hear that. Martin didn’t want it to be a straight-ahead sound: there’s this straight recording band and that’s it, finished. He wanted to warp it quite a lot, and sometimes we liked that and sometimes we didn’t.

Unknown Pleasures was our first outing and we’d played it live a few times, and it was powerful, almost heavy-metal kind of stuff to us. Two things Ian said. One, he never wanted to get any bigger than the Kinks ever got. Two, that what he wanted to do was to get onto the heavy-metal circuit in America, which was really weird. He really loved the Stooges, and he wanted to get into what the Stooges were into.

So the music was quite loud and heavy, and we felt that Martin had toned it down, especially with the guitars, taken out the more raucous elements of it. So we didn’t actually like Unknown Pleasures. It inflicted this dark, doomy mood over the album: we’d drawn a picture in black and white, and he’d coloured it in for us. We resented that, but Rob loved it, and Wilson loved it, and the press loved it, and the public loved it, so we were just the poor stupid musicians who wrote it. We swallowed our pride and went with it.

Peter Hook: Everything I’ve read about Unknown Pleasures says that the first pressing was five thousand, and it wasn’t five thousand, it was ten thousand, because Rob and I carried them up the stairs into Palatine Road.

Stephen Morris: There was definitely an upward trajectory once we’d done Unknown Pleasures. We’d had all that time when we were just practising and practising, writing stuff, and then once we got to make a record of it, it took on a life of its own. After Unknown Pleasures, when people were trying to be nice to you, you were sort of, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah, you weren’t like that the other week, were you?’ We didn’t exactly take the praise in the way that perhaps we should have done.

We did have a chip on our shoulders about the old Manchester mafia. We still had a bit of ‘don’t care’ in front of the music press, because we couldn’t understand a lot of the words that they used in the reviews anyway: ‘What the bloody hell are they going on about?’ It was just a record, so we took it all with a pinch of salt. When at gigs punters came up to you and said they really liked it, that actually meant something, but the reviews just baffled me.

Peter Hook: We just carried on doing what we did. In those days you were literally doing everything yourself. It was very difficult and it was really hard work. You had to set your own gear up, pull your own gear down, and it was very unglamorous. Even while you were Joy Division and Unknown Pleasures, travelling to and from the places was still really hard, and you didn’t have any of the glamour, to be honest.

Charles Shaar Murray, ‘Heads Down No Nonsense Mindless Poetry’, John Cooper Clarke interview, in NME, 7 July 1979

Onstage, Joy Division ram dark slabs of organised noise at the audience while a scarecrow singer moves like James Brown in hell. Acidrock a decade or so on. It is whispered that acid enjoys considerable allegiance from a lot of the young postpunks in Manchester. As the bassist triggers a synthesiser and a skin breaks on the snare drum and the band’s sound begins to resemble Awful Things carved out of smooth black marble, who could argue?

- 13 July 1979: Russell Club, Hulme

Kevin Cummins: They did two gigs quite close together at the Factory, in June and July that year, and Martin did the live sound at one of them. It was around the time that the album was coming out. Suddenly it all started to make sense. The band didn’t like the sound: it was too arty. But for us, their sound was fuller, they’d hugely fulfilled their potential with that album, and we all thought that was going to be the album of the year. It was astonishing to think that about six or nine months earlier, we thought they were a bit of a joke band.

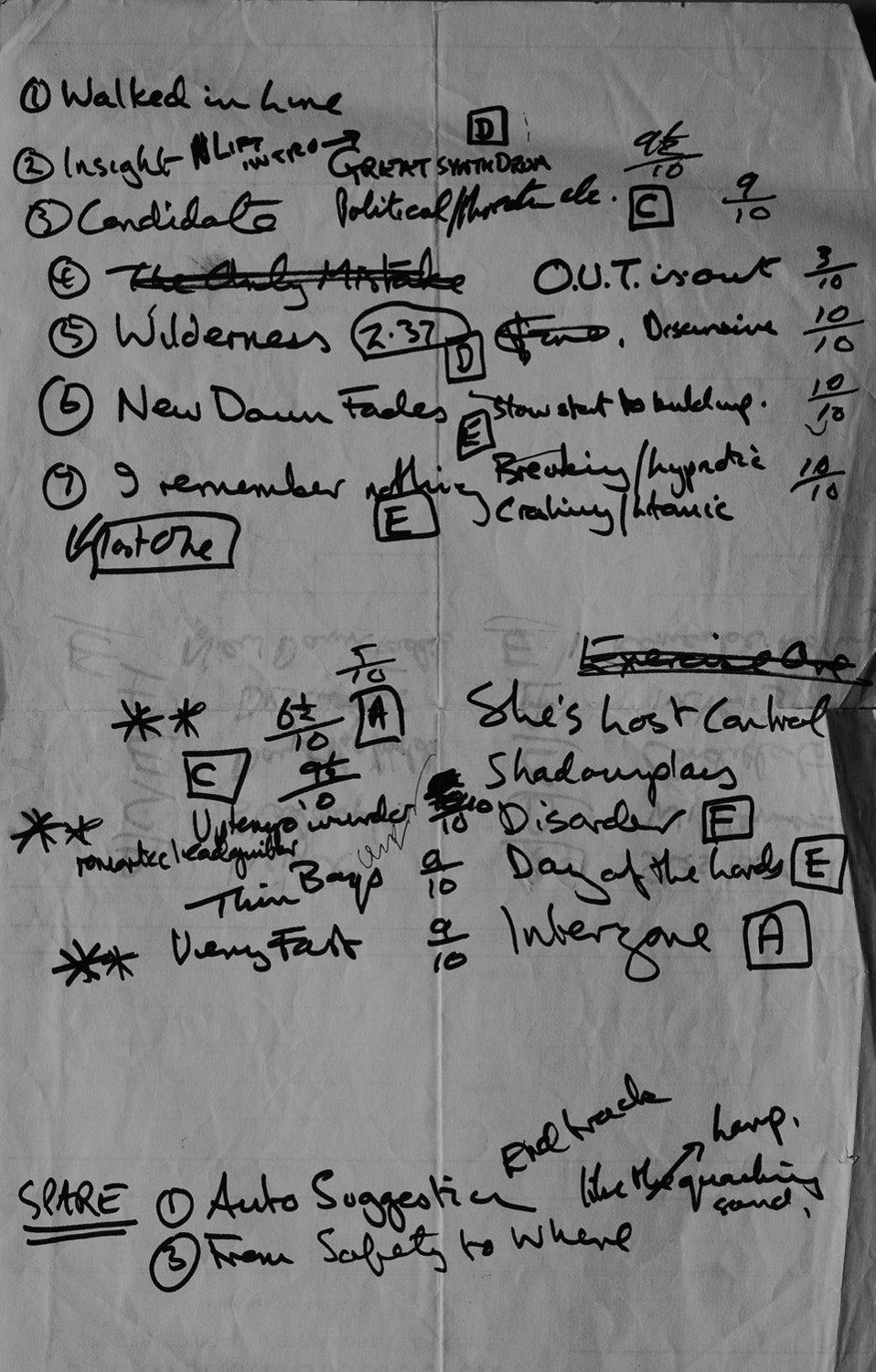

Alan Hempsall: Crispy Ambulance supported Joy Division at the Russell Club, July the thirteenth. It was one of the first gigs they did after the album came out. Joy Division started with ‘Dead Souls’, which I don’t think I’d heard before. They were never ones to pander: if they had any new material, they would play it. ‘Dead Souls’ is still one of my favourite tracks. I like the way it builds and the way Ian holds back and doesn’t launch in until the song’s halfway over, which was something I always thought, ‘That’s a clever trick, there’s not many singers with that self-discipline.’

Roger Mitchell, review of Unknown Pleasures, City Fun, issue 8, July 1979

It is a truly remarkable debut mainly due to their originality and their own policy of non-compromise. Probably the best debut album since 1977 and ‘The Clash’.

Jon Savage, review of Unknown Pleasures, Melody Maker, 21 July 1979

‘To the centre of the city in the night waiting for you …’ Joy Division’s spatial, circular themes and Martin Hannett’s shiny, waking-dream production gloss are one perfect reflection of Manchester’s dark spaces and empty places, endless sodium lights and hidden semis seen from a speeding car, vacant industrial sites – the endless detritus of the 19th century – seen gaping like rotten teeth from an orange bus.

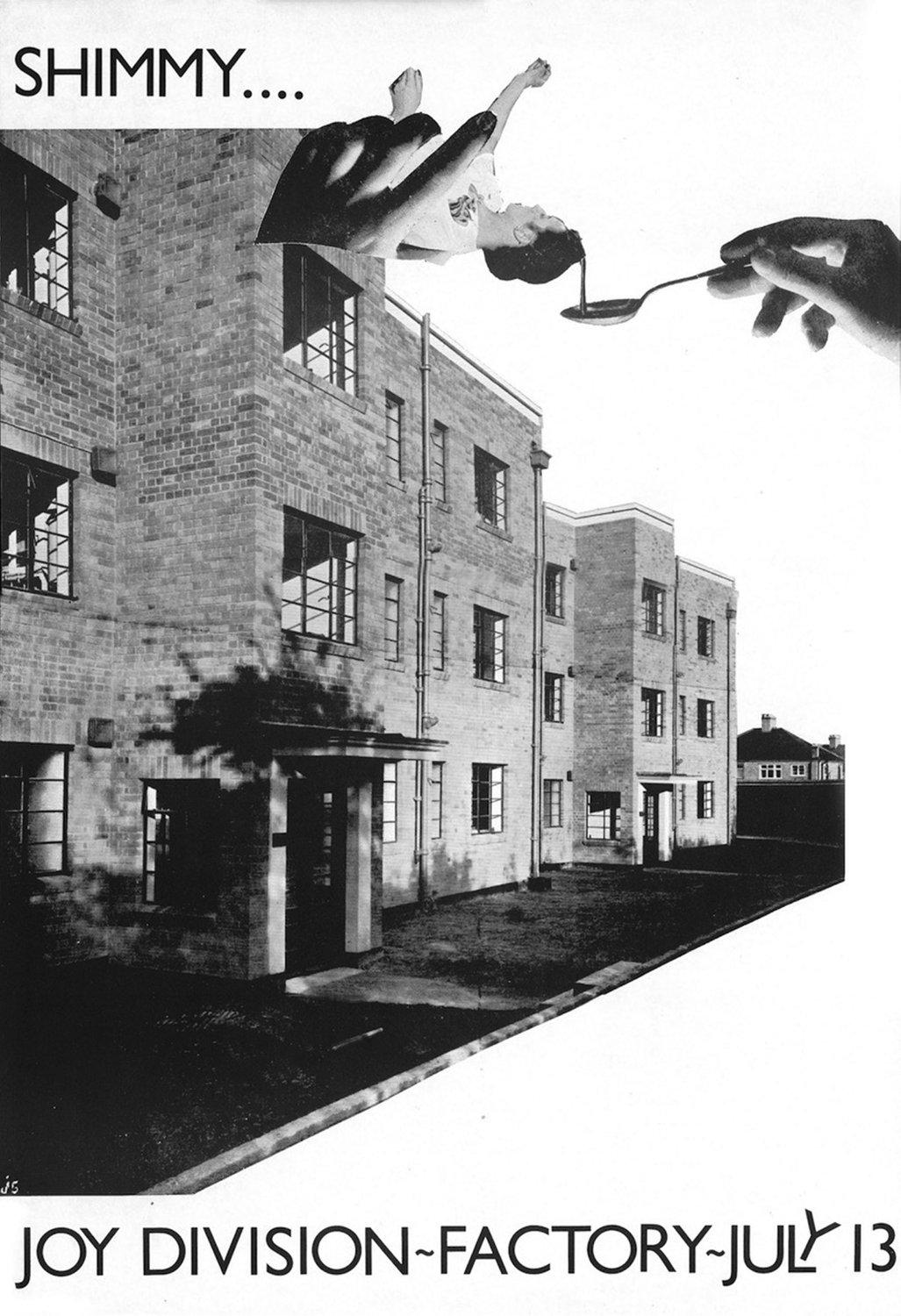

‘Shimmy’: Poster for Joy Division at the Factory, 13 July 1979 (Courtesy of Jon Savage)

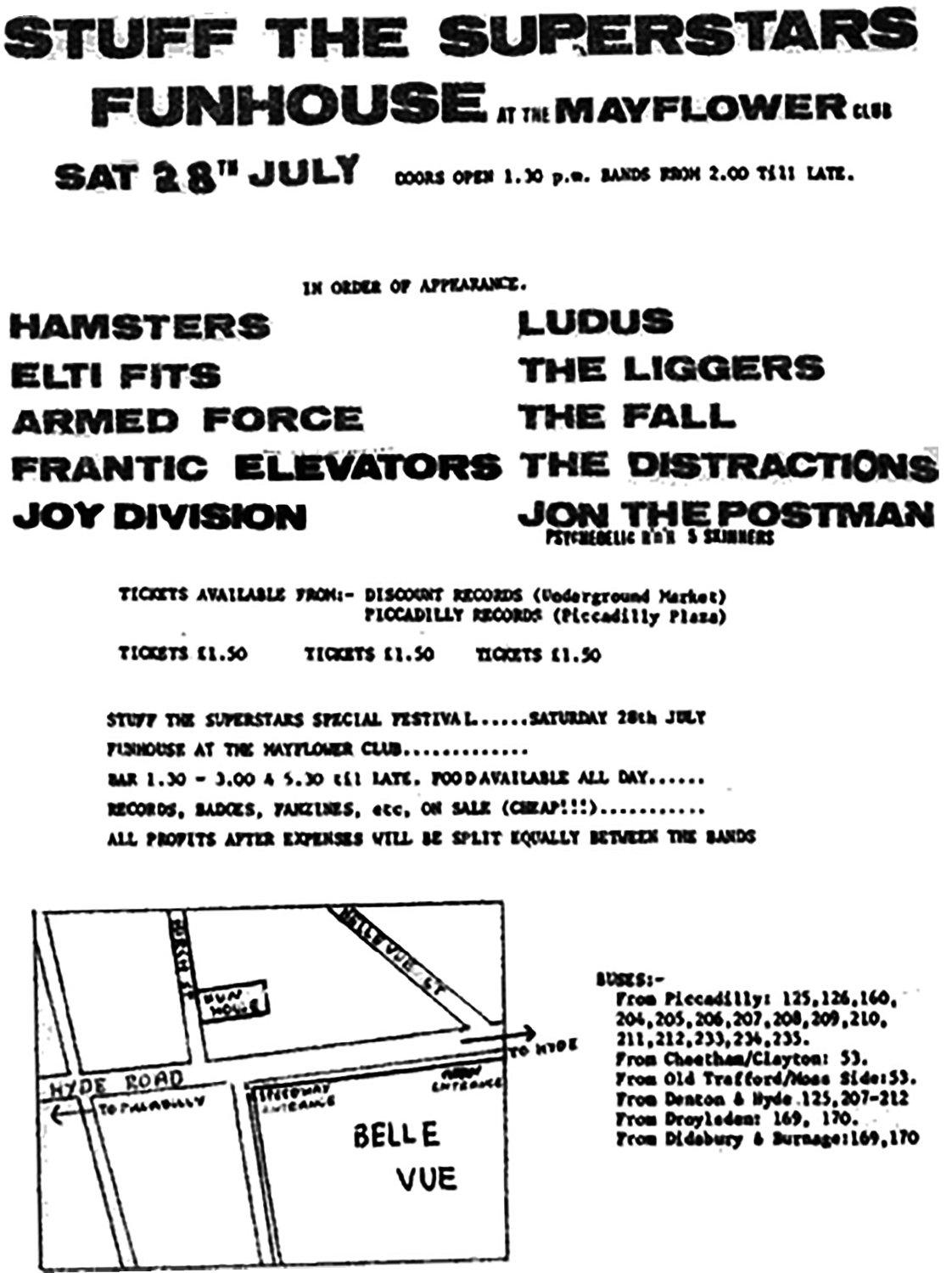

City Fun review of Joy Division at the ‘Stuff the Superstars Special’, Manchester, 28 July 1979

Their manager reads a book during most of the evening. No, it’s not a pose, he’s a genuinely serious bloke, well into philosophy and such. He sees it as a job to do (and he’s rather good at it). He’s not impressed by the hype, the ‘next big thing’ bit. He knew they were a big thing years ago. Joy Division, in one form or another, were in at the start. THEY knew where they were going, even if we didn’t. THEY WERE BRILLIANT, I MEAN BRILLIANT!

Liz Naylor: I saw Joy Division a series of times at the Factory, leading up to the ‘Stuff the Superstars’ gig at the Mayflower, which was promoted by City Fun. They were on a day-long bill with the Fall and Ludus, and lots of also-ran bands and the appalling John the Postman. It’s interesting that Joy Division really crossed over. They weren’t like a snotty Factory band; they actually aligned themselves with a certain other kind of group in Manchester, and I think that’s really evidenced by the line-up at that gig.

The Mayflower was fantastic. It was my all-time top favourite venue. It had been built as a cinema in the twenties, when it was called the Coronet, and then in the fifties and sixties it was a dance hall called the Southern Sporting Club. It’s absolutely embedded in a very working-class area of Manchester called Gorton, which is where Myra Hindley was from: terraced houses, white working-class Manchester as it was in the post-war years. In the seventies it used to hold gigs which nobody else would put on: reggae gigs and things that were considered a bit dodgy.

The venue was just crumbling, I mean it was absolutely dank. I can remember going in, and it certainly had no house PA or anything, so it was just like a big, dank, old empty building with a barely functioning bar – I think you could buy cans of beer – and it smelled. It had an upper level that was shut because it was structurally dangerous, so it was a big, black, empty hall. It was a really melancholy building actually; it had plants growing out of bits of its walls because it was so damp.

When Unknown Pleasures came out, I went to Palatine Road and was given a free copy, but I didn’t have a record player, so I took it to the Mayflower, and there must have been a City Fun gig there. I played it over the PA, so that was the very first moment I heard the album sort of booming through this bad PA in this huge damp room, and of course it was absolutely perfect. You fell in love with it, it just meant everything – ‘This is the ambient music for my environment.’

I was just very swept up in them. I was young and I wasn’t able to stand back and think, ‘Mm, they were a good band.’ They were like an extension of me, it just felt there was no boundary between me and what I was experiencing. They were really important to me. I think I saw them probably about seven or eight times. I didn’t have any sense of a good or bad performance actually, they were just there for me. Other bands I’d go and see and I’d have an opinion on, but Joy Division were my ambient world.

That’s the thing about Joy Division: they were a very interesting band about time because they’re very informed by the past, but also you’re always propelled into the present with them. So time stops a little. Ian’s performance to me was like time just stopping. Joy Division were of a particular time and a place, and once you take them out of that their meaning changes. It’s like collectively they relayed the aura of Manchester in that period. They are what Manchester was like. Subsequently, that kind of aura has been slightly pushed onto Ian as an individual, and I think that’s erroneous. As a band they’re much more important than one individual or what his vision was, because I don’t think it was his vision, I think it was the ambience of Manchester.

Bernard Sumner: Ian had a desire to explore the extremes. There’s two types of people in this world: there’s people who are extremists and they want to taste the extremes, get extremely drunk or not drink at all, and there’s people who take the middle way. I’d say I’m pretty much the middle way, but Ian wanted everything to be extreme: extreme music, manic performances. So the music was extremely dark. Even after we recorded Unknown Pleasures I found it quite difficult to listen to because it was so dark.

‘Stuff the Superstars’ gig at the Mayflower (from City Fun), 28 July 1979

I don’t think the production helped because that made it darker, even darker still, but I felt, ‘No one’s going to listen to this, it’s too bloody heavy, too impenetrable.’ Also, I think in our lives we’d all had very dark experiences. We were only twenty-one, but for me, say, I’d had a very difficult upbringing and I had a lot of death and illness in my family: my mother had cerebral palsy; my grandmother, who we grew up with, had had an operation on her eyes that went wrong, so she’d lost her sight; my stepfather got cancer from smoking.

My grandfather was ill as well – he had a brain tumour – and all this had been going on when I was very young. I had all this tragedy within my family. I’d had to witness a couple of them dying at quite a young age, and that definitely had an effect on me. To experience such things at a young age makes you quite a serious person. I was sixteen when it started, when my grandfather died. And being an only child makes it worse. I know Hooky had had a few troubles at home, and Ian, I guess, in his line of work was quite serious. For me, life was serious, so I guess that came out in my music, subconsciously.

I’d had quite a lot of loss in my life. The place where I used to live, and where I had my happiest memories – and let’s face it, everybody’s happiest memories are from when you’re a kid and every day was sunny, there’s no inhibitions and no hang-ups – well, all that had gone. All that was left was a chemical factory. It’s all gone – the houses, the people. So there’s this void that you can never, ever go back to. When I was twenty-two I realised that I could never go back to that happiness. So, for me, Joy Division was about the death of my community and my childhood.

Liz Naylor: I don’t know how Joy Division managed to relate to Manchester. I don’t think they were conscious of it. Bernard is somebody that was rehoused into a post-war development. They had the dislocated relationship with community and city just because of the age they were. I think it’s purely an accident of history. Their experience of Manchester was of being in communities, then being rehoused.

Their experience of the city would have been not dissimilar from mine, going in there during the mid-seventies, pre-punk times, where it was really failing and emptying out, decaying and derelict. I think it was a really strange kind of hitch in time and place, the very last days of an industrial city. That created a really unique moment, an ambience, and that kind of ambience can be traced still through psychogeography in the city as it is now, because those moments are never, ever truly eradicated.

I suppose the environment totally mirrored my inner self. I felt really comfortable in it. It’s interesting reading the Deborah Curtis book: the places, the clubs that Ian was going to and the places that I was going to – the New Union on Princess Street, which was the vilest pub, and the Mayflower Club, and I went to a club called Dickens, on Oldham Street. These were identified as gay places, but that doesn’t really tell you anything, because the people in them were freaks, they were people who were left in the city after everybody who could had moved out.

C. P. Lee: The whole zeitgeist of the late seventies fed into Joy Division. You’ve got this group of young guys from these towns in the north-west of England who could not help but be informed by the atmosphere that was around them. When I hear them now I can see how it directly transmuted into the music that they were playing. There’s a definite feeling of ritual in Joy Division performances and Joy Division releases – ‘release’ being the operative word, in that you can transcend and move beyond and get onto another plane of being.

Mark Reeder: I loved the Joy Division records. I was in awe. Unknown Pleasures, I couldn’t imagine it being any better, it was just perfect for that moment. When Rob sent me the first box of Unknown Pleasures, I couldn’t believe my ears. The album just blew my mind. Everything about it: the cover, the mystique of the inner sleeve – the hand at the door. Fantastic. ‘New Dawn Fades’, I couldn’t stop playing that. It just hit a chord with me, that song, but I loved every single song on that album.

Jon Wozencroft: Unknown Pleasures was such a devastating moment, because from the Factory Sample to the album within six months was an extraordinary development, and most importantly in the sense that there was a complete world in itself. It was like a really good long film that you didn’t want to end. There was no question of a thirty-eight-minute album or a forty-five-minute album or anything like that; it was just exactly right for the experience that it sought to communicate.

It’s very exciting because you have been taken on a journey. Ian comes on, track one, side one, and he says, ‘I’m waiting for a guide to come and take me by the hand’ – that’s it, you’re in it straight away.

Iain Gray: I found Unknown Pleasures a frightening album, and that was when Ian was alive. I can remember listening to it late at night and thinking, ‘It’s quite creepy.’ It caught the essence of despair. You always think, even if you knew someone slightly, that you should have gone, ‘Are you OK?’

Richard Boon: I thought it was a great Martin Hannett record. I thought some of it was very forced, some of the vocals were very mannered. I think the vocals were a bit too upfront, and you get the sense that the delivery is very sort of artificially intense, not really coming from his heart. Once Martin had reshaped them – he was their Svengali, much more than Wilson or Gretton – and they could achieve the sound that he’d brought out of them, it eased up a lot and wasn’t as formal and forced as I perceived it to be.

Bob Dickinson: Joy Division sounded like ghosts and seemed spectral at the time, and their music still does have that quality about it, of something that’s dead but it’s alive, something that’s there and it’s not there. The other phrase that comes to mind is that technology has turned us all into ghosts; that the recording medium and the visual recording medium, as well as the audio recording medium, are turning you into a dateable object and they’re killing you. I think that they were aware of it, and they were haunted by it themselves and they described that condition, which is what makes their music so relevant and still so powerful.

- 2 August 1979: live at the Prince of Wales Conference Centre, YMCA, London

Jill Furmanovsky: They were compelling. Ian looked like a schoolboy in his grey shirt and trousers. Then there was Hooky, with that low-slung bass. He had a particular way of playing that was quite unusual. Bernard, too – they just looked very un-rockstar-like. More like the Fall, from that point of view. I was very struck by Ian Curtis: he looked like he’d bunked off school and gone to join a rock band, which in a way he had done.

After the gig I went backstage and poked my head into their dressing room. They were in a good mood, the gig had gone well, friends were arriving, and I had a few minutes, and that was the extent of my shoot. I just whizzed in and whizzed out; I didn’t get to know them at all. They must have known who I was, cos I’d worked with Buzzcocks and some of the other punk bands, and I probably just said, ‘I’m Jill Furmanovsky from [whichever newspaper I was working for], is it all right if I take a few snaps in the dressing room?’ And they didn’t mind. I snapped, and I left.

They were all rather jolly, sharing out cigarettes, having a drink. They were in good spirits. The other bands – Monochrome Set was one of them – they were all popping in and out. I’m very quick at what I do; a lot of my best jobs are done very fast, in a hotel room or a dressing room, places like that. It was immediately after the gig, and the main shot, which we always use, it looks like they’re exploding from one point. I always liked the composition of that, with Ian leaning over, but building up to that there was a lot of movement going on.

Seeing Ian Curtis with a towel around him and not minding somebody being in the room, there was a feeling of having cracked that gig. I think it was quite an important London gig for them at the time. There must have been a buzz about them.

Adrian Thrills, review of YMCA concert in NME, 11 August 1979

Joy Division were phenomenal … Each member is equally important. Drummer Steve Morris is undoubtedly the best ‘thumper’ since the sadly exiled Palmolive of Slits/Raincoats fame. His style is also remarkable for the combination of ordinary drums and electronic percussion and syndrums, particularly devastating on She’s Lost Control and the Insight encore. Peter Hook swerves and dips on bass like a more menacing Paul Simonon, while guitarist Bernard Dickens [sic] remains sternly still beside Ian Curtis who sings and growls as he grimly jerks like a puppet on invisible strings.

Steve Taylor, review of YMCA concert in Melody Maker, 11 August 1979

Joy Division speak of apocalypse hopelessness and fragmentation, yet their music acts as an exorcism of passivity and neglect, as near a revitalisation of the spirit of primeval rock ’n’ roll as I’ve experienced in a long while.

Dave McCullough, ‘Truth, Justice and the Mancunian Way’, Sounds interview, 11 August 1979

The irony was, of course, that even by, as they thought, remaining inscrutable and, ahem, Obscure, the band provided us with gargantuan evidence of their pseudness and, more to the point, their cerebral shortcomings. Ian remained contentedly silent as I became increasingly irritated by the absurd masquerade that was taking place.

Bernard Sumner: I think it was one of our first interviews. It was such a horrible experience we just thought, ‘Fuck it, if that’s what they’re like, we won’t do them.’ So we just didn’t do them. I think Ian might have done a couple, but it wasn’t the fun bit. We were only doing it for fun, we had no idea of promoting ourselves. We weren’t bothered about getting on Top of the Pops or selling vast quantities of records, we just liked it at that moment and that’s all we were interested in. We didn’t have any idea that if you do loads of interviews, you’ll sell more records.

Dave McCullough was pretty off-putting, because he was just a knobhead basically. We weren’t being unreasonable or anything, we were just okay with him, and when we didn’t follow his little plan, he just went off on one, so we just thought, ‘Fuck it. Stick to making records.’ Of course, my opinion of journalists is totally changed now. I think they’re wonderful.

Peter Hook: Rob was the thinker. He had the vision in the way we were portrayed. When the press came along, spouting this rubbish at you, in the same way that you annoyed the other bands when you began you annoyed the press, because basically they were a bunch of tossers. We wouldn’t play the game. We’d answer questions with the word ‘no’. They didn’t seem to warrant taxing yourself. They’d ask you one question, and then expect you to fill their column inches for them with one answer. They got what they deserved.

Ian was very shy, especially early on. Steve didn’t want to say anything, me and Bernard were a pair of pissed-up yobs, so Rob said, ‘Listen, it’s probably better if you two don’t say anything, because you’re both as thick as pigshit.’ And we went, ‘That’s all right, yeah, we can agree with you on that one.’ You didn’t know what you were doing, you were just doing it. Ian may have known what we were doing, but he fell behind me and Bernard because we were mouthy, gobby.

Rob stopped us really. It changed later, because Ian used to hate it when people would only talk to him about the group, he hated people singling him out in Joy Division, so that again put you on a spot where you didn’t want to talk to the press. Every interview that you see or read about a group starts roughly the same. They’re all as boring as shite really. I’d rather not know where the music comes from, I’d rather it was magical and just existed like that, so I was quite happy to go along with not doing interviews. I think it breaks the mystery.

We were very insular. While it may annoy you, you still got strength from being together. Rob was really, really good at bullying us along. You know, ‘Come on, come on, fuck that.’ He’d keep us at it really. If something happened to bring us down, he’d boost the whole thing and push us along, and then we’d forget it because he’d stand up for you. If there was somebody there that he felt was doing something wrong, he’d say, ‘Fuck off, you knobhead, you fucking twat, it’s my band, this’ – which was great. You really felt he was rooting for you.

James Brown, sabotagetimes.com

Stephen Morris: The first time I realised something had changed was when we played the Nashville. We went out and there was a queue of people like I’d never seen before, round the block to get into the Nashville Rooms. I said, ‘Look at that, that’s our first queue.’

Paul Rambali, ‘Joy Division: Take No Prisoners, Leave No Clues’, NME, 11 August 1979

Were you to shine a torch around this subterranean scene you would see the young, tidy faces of Joy Division and notice perhaps the ordinary neat cut of their clothes. An unremarkable image, with the barest hint of the regimental overtones of their name in the flap-pocket shirts two of them are wearing. You might also notice the growing excitement in the faces of the onlookers, by now all locking into the irresistible motion of the music. Easily the strongest new music to come out of this country this year.

- 13 August 1979: Nashville Rooms, London

Ian Curtis (interviewed by Paul Rambali, NME, 11 August 1979): You’re always working to the next song. No matter how many songs you’ve done, you’re always looking for the next one. Basically we play what we want. It’d be very easy for us to say: well, all these people seem to like such and such a song … it’d be easy to knock out another one. But we don’t.

We don’t want to get diluted, really, and by staying at Factory at the moment we’re free to do what we want. There’s no one restricting us or the music – or even the artwork and promotion. You get bands that are given huge advances – loans really – but what do they spend it on? What is all that money going to get? Is it going to make the music any better?

Terry Mason: It was like a snowball how they were growing at that stage. We were getting more and more press, and you start taking on what the press are saying. You’ve had this period where no one wanted to know you, and all of a sudden people are saying, ‘You’re fantastic,’ and that brought more confidence into the band, and they started going onstage with more of a swagger about them. They were a lot more sure of themselves.

Tony Wilson: I don’t think I saw them becoming world-beaters fast because I presumed from the very beginning they were world-beaters. I presumed they’re the most important band of their generation, like the Pistols had been two years before. It would be nice to think I didn’t know it at the time, but I did know it, and no, it was not a surprise. They just got better and better.

Bernard Sumner: We’d always relied on what we thought about ourselves. We didn’t really care what other people thought. Because I think we were quite disliked at the start – I don’t know, it could be my own paranoia – we learned to rely on ourselves. I mean, me personally, I was an only child, so I have that way of thinking anyway, self-reliance.

I always felt that was a wonderful strength of Joy Division – that we only really cared if we liked it – and that gave us longevity. We didn’t know how it worked either, we were on an independent label. We didn’t think of it in careerist terms; we were just happy to be getting £50 a week, £100 a week or whatever and doing what we loved doing: travelling around the country, travelling around Europe, playing gigs. It was fantastic. That was enough for us, because it was good: we were having a great time on the road, partying and all the rest.

- 19 August 1979: photo session with Kevin Cummins at T. J. Davidson’s Rehearsal Rooms

Kevin Cummins: I’d been to see them rehearse a couple of times and hadn’t taken photographs; I’d just been along, because I was interested in what they were doing by then. I’d already photographed Buzzcocks and the Fall in there. I thought I might need to take some lights, to fill in a bit. Also, as you know, bands are notorious for not turning up on time and starting work at midnight or something. So I went in a couple of times to watch them rehearse for an hour or so.

Then I went down that day and took the pictures. Most of it is shot against the light. I liked the silhouette, shadow kind of feel for them. Which kind of became the way other people shot them. You can see lots of Coke cans and things in the shot, and the Coke cans are all full of piss. The place stank, it was disgusting. The toilets were on the floor below, and they couldn’t be bothered going down there, they just used to piss in Coke cans, and they’d be dotted around the place, so you didn’t dare touch anything.

Bernard Sumner: T. J. Davidson was the guy that ran the rehearsal space. He looked a bit like the drummer out of Frankie Goes to Hollywood, with the Scouse perm, but he was a really nice guy. I think his dad owned a jeweller’s shop and bought these old factories in Manchester. We had an enormous factory floor to ourselves. Half the windows were smashed in and there were rats in the toilets and there was no soundproofing, so you could hear down below you. Did we have Slaughter and the Dogs down below us?

In the winter we used to brush all the rubbish to one end of the room and set fire to it just to keep warm. There was a hole in the floorboards, and you could see Slaughter and the Dogs’ drum kit. Hooky used to piss through the hole in the floor onto their drum kit – when they’d gone, of course – because they were so annoying and loud. It was a good creative space, but it was bloody freezing. He wouldn’t put the heating on. I guess it didn’t work, but it was so cold. The acoustics were awful and our equipment was awful, but we managed to write some great songs there.

- 27 August 1979: Open-Air Festival, Leigh

Jon Savage, review of Leigh Festival in Melody Maker, 8 September 1979

Joy Division exorcised the increasing cold with cinematic, metallic blocks of noise.

Kevin Cummins: We drove in and parked about fifty yards from the stage, and just left the car there. There was a row of cars, cos there was hardly anybody there. It was quite exposed. I took pictures of Hooky wearing his overcoat onstage, and it’s the middle of August. It was just one of those things that was so badly organised. The poster wasn’t ready, so nobody knew it was on, then nobody could get there because there was a public-transport strike, so the only people there were the people who could drive.

The whole day there was hardly anybody there, and then it filled up a bit in the evening when Joy Division came on. Being able to shoot onstage with them was quite exciting for me. I was onstage pretty much for the whole gig. I always enjoy that because you get to feel what the band are feeling.

Peter Hook: I remember playing at Leigh Festival. That wasn’t a great gig. It didn’t feel very good, it was really cold. The highlight was the forty-inch turd in the toilet that Terry found.

Jeremy Kerr: Everyone got busted on the way in. There was more coppers than audience.

Lesley Gilbert: It was like ten people in the field, and that was it. I think there were more police there than there were crowd. They were stopping everybody when they went in, and I’m sure they took Bernard’s girlfriend Sue away somewhere and searched her. It didn’t faze anybody that there was hardly anybody there, it was good fun. There was loads of stuff like that, gigs where there was hardly anybody there and nobody was bothered.

Stephen Morris: Leigh Festival – what a washout. Factory meets Zoo halfway. It seemed like an awfully big field, and my abiding memory of that was as soon as it started raining, the twenty or thirty people that were there went and got in their cars and turned their lights on. ‘Where have they gone? Oh, they’re in their cars, that’s all right.’ It was bound to be a washout. A lot of Factory ideas must have grown out of some late-night conversation, and if they’d just waited a few hours before making these decisions, they probably would have seen the error of their ways, but no, we’ll go through hell or high water and damn the consequences.

- 8 September 1979: Futurama Festival, Leeds

Terry Mason: A major gig, of course, was Futurama. We were on there same night as Public Image, Johnny Rotten’s new band, and we were the slot right before them.

Kevin Cummins: For them, it was great, but the whole event was awful. It was everything that punk was against – a huge festival in a draughty hall in Leeds, the Queen’s Hall. They hadn’t even cleaned it out, it was sparsely attended, and all the rubbish that was stored in there they just swept to the back of the hall and put a bit of fencing in front. It was a firetrap, to be honest. There was an arena-style stage and rig. It was very cold and it was grim.

It was relentless, band after band after band. Until Joy Division came on, it was fairly awful. It worked for them, without being clichéd, that almost Eastern European feel. I don’t think it was even what they intended it to be, it just worked like that. As a photographer, Ian’s dancing was quite tricky. There were different ways of doing it: you could shoot at a lower shutter speed and get some movement, or you could use a bit of fill-in flash and get him, but still get some movement coming off his arms.

I just wanted to capture the intensity of his performance. It was mesmerising. It always felt dangerous, because you always felt he was slightly out of control, and I’d not really experienced that with any other band. I’ d seen the Clash and the Jam and all these bands, and I never felt that they were more than the sum of their parts. But with Ian, it was dangerous. The only other person who was that dangerous onstage was Iggy Pop.

Dave Simpson: It was the first gig I ever went to. It was a place called the Queen’s Hall, which is not there any more. It was on Swinegate, they flattened it in the mid-eighties. I remember it vividly because I used to go to flea markets there. The sound was very distinctive. I’ve got a couple of tapes of it, and as soon as I hear those tapes, I’m instantly back there. At the time I was fifteen or sixteen, never been to a gig before, had nothing to compare it to.

The first thing I remember was the size of the speakers. I’d never seen a proper PA system. I was used to music coming out of a transistor radio, or at best a home stereo. So to be confronted by these speakers that were probably about fifteen feet high, it was like going into another world. I was blown away. It was a really weird echoey sound, but if you listen to the tape, I think it actually enhances it. The way the drums sound, with this massive, giant, reverb-soaked pounding, it just sounds incredible. To me as a kid, it just sounded spookier.

Before Joy Division came on, there were other bands that were using strobes, which, again, I’d never seen before. Hawkwind had lent their laser system to Punishment of Luxury, who I also thought were fantastic that day. It all felt quite futuristic, which it was supposed to be. It was billed as the ‘world’s first science-fiction music festival’, which was a grand idea, to put all these forward-looking bands on, with a few special effects, like lasers. There was a couple of people walking around dressed as robots. A very rudimentary vision of the future.

I’d seen their name. On the bus route to my school, there used to be a lot of posters for a venue called the Roots Club in Chapeltown, and I’d seen their name, they played there. I think they’d also played the Fan Club in Brannigan’s. That was outside the city centre, more in the West Indian area, as it was then. They had reggae on there and Pink Military or Pink Industry, Cabaret Voltaire – I suppose the esoteric end of the post-punk era. So they had played in Leeds, but I don’t think people really knew who they were.

When A Certain Ratio were on, I remember someone turning to me and asking, ‘Who’s this?’ And I said I didn’t know, I thought it might be Joy Division. I’d never heard of either of them, they were just names on a poster. No idea what they looked like or sounded like. I realised my faux pas when Tony Wilson came on, an hour or two later, and introduced Joy Division as ‘the awesome Joy Division’. Two things crossed my mind: one, that this was going to be great; and two, ‘Oh, the other band wasn’t Joy Division then, so who were they?’

Joy Division absolutely mesmerised me. It was like seeing the future. They started with ‘Dead Souls’, which was another weird thing, because I was used to songs having ten-second intros, then the verse comes in, then the chorus. You don’t expect a song that begins with about a minute and a half of bass and drums, a tiny bit of guitar and nothing else. The singer not singing at all, just dancing. ‘What is this, an instrumental? Who’s this bloke dancing?’ Then the dancer starts singing, and it starts to fall into place.

I remember Peter Hook putting his boot on the monitor to play ‘Transmission’. They played ‘Wilderness’ and ‘I Remember Nothing’, and it sounded amazing because of the reverb on the drums. Ian wore a shiny kind of two-tone shirt, looked fantastic under the lights. I don’t remember him really saying anything. He might have said, ‘Good evening, we’re Joy Division.’ They just came on and played the music. I loved the mystery of it. These four reasonably young guys playing the music and taking you to all manner of emotions, and yet nothing was explained.

It completely changed my life. Virtually everything I’ve ever done since that gig has been because of it. Another thing: you had to have your photo taken to get an ID card to get in. So before we went in, me and my mate Bruce had to go to Woolworths and get these photos done, and in this photo-booth picture of me I’ve got this iron-on Sid Vicious T-shirt, a very crap Vapors/Members-type spiky haircut, and Bruce’s arm is coming in through the curtain. I’m looking up, laughing at this arm coming in, and the camera goes off.

I look at that picture now and I think, ‘Within a couple of hours of that picture, you were never the same again.’ The T-shirt went on Monday morning – it literally changed everything. I remember getting rid of loads of records. Suddenly I wasn’t going to listen to Sham 69 or the UK Subs any more, I was going to listen to Joy Division, the Bunnymen, that John Peel kind of thing.

Damaged Goods fanzine, no. 4

Well, on to the two song wonders, Factory Records artists (actors–?) Joy Division. Why does everyone love Joy Division? Who knows, certainly not I, but it’s like one BIG HYPE. ‘Shadowplay’ and ‘She’s Lost Control’ are the only two songs in their set that I’ve any time for at all, the rest just being a monotonous drone! Come on you modern boys, look through the Gothic air of intrigue, the nazi name connections, the stylised ‘Kentucky-fried’ dancing and what do you see – NOTHING, IT’S ALL A POSE! Finito. PS. Is Tony Wilson this year’s McClaren?

- 13 September 1979: No City Fun: The Factory Flick (Factory FAC 9), 8mm film, premiered at the Scala Cinema, London, with words from ‘No City Fun’ by Liz Naylor and a soundtrack of Unknown Pleasures

Liz Naylor: ‘No City Fun’, City Fun magazine, issue 3, December 1978

manchester where are you? I NEED. I walk around and try real hard to look like a famous writer, with a cigarette dangling beautifully from my lip, dylan thomas has the edge. no one is impressed. no one is convinced ….. me neither ……. right where are people? virgin at the time of writing is closed – THANK GOD, (wish they’d stay closed for good). due to moving (CERTAINLY NOT MOVEMENT, CERTAINLY NOT PROGRESSION.) I mooch down to the underground – HORROR MOVIE, girls with dyed hair and split skirts hate me, fifteen year old schoolboys buy overpriced Clash singles and say ‘fab’ ejaculate over blondie albums (now you know why they have plastic covers on them!) I swing out, last years [sic] thing etc etc etc etc

Liz Naylor: I was so amazed that this thing I’d written had become this other thing, and it felt like a life-saving moment. I don’t know what I thought would happen – I’d be signed up by Hollywood. For so long, I’d lived at home, I’d been an utter freak, I’d been queer and on my own, and it’s like having no presence in the world or no voice, so suddenly not only had this thing been published but it had been made into a film, and it felt like my vision of Manchester made real.

Looking back at it now, I realise that it’s not just my vision. I believe that was the ambience of Manchester, which is why I think Charles Salem chose Joy Division’s music, because he recognised something of similarity there. We were talking about the same thing, experiencing the same place at the same time. Looking at it now, I do think it’s a psychogeographical film, it feels very situationist, all the stuff with shop fronts, and it looks like a crude piece of English situationism – which is fantastic.

[Looks at film] Oh, we’re in the Arndale now. Okay. Oh, there’s Paperchase – I can’t even remember that. Underground market. Watching it now, I can kind of identify most shots where they were, and it is like being pulled back into that journey again, and it really picks up on the moods of the city in that period. It’s such an unconscious piece of film-making and it was a rather self-conscious piece of writing, but with a piece of unconscious film-making it creates something quite strange.

- 15 September 1979: Something Else, BBC TV

(Interview as transmitted)

Tony Wilson: Do you think they will ever play your records?

Stephen Morris: Doubtful, doubtful.

Paul Burnett: Is there an automatic right that you have when you bring a record out that it should get played on Radio 1?

Tony Wilson: If it’s a brilliant record, if it’s better than most of the dross that’s around, and there are records which are better than most of the dross which is around that don’t get played because they are slightly unsettling – for the simple reason that they come from somewhere slightly deeper in the soul than the level of a pure hit factory – and those things don’t get played.

Stephen Morris: Something Else was good. That was where we discovered you could get your hair cut by the make-up ladies. If you went, you could get free haircuts; you could also go into the canteen and get ridiculously subsidised food – it was very, very cheap. Also, I got to say something on television, just the once. We did it with the Jam, which is where Paul Weller noticed us. After that, the Jam did ‘Start’, and Ian always said they nicked that off us.

Tony Wilson: If you compare the first television, which is ‘Shadowplay’ for Granada, to the BBC stuff from a year later, there’s a real difference, because they really go for it. I think the performance on the BBC Something Else show is phenomenal. It’s wonderful to have ‘Shadowplay’ there, and to have the first television visuals of Joy Division, but to have the BBC footage, that is so intense.

Jon Wozencroft: It was in September ’79. I had to go back into hospital for a bone-graft operation because I broke my collarbone very badly and had to be stitched up with bone material. I was just recovering from that, and I went into the television room on a Saturday afternoon and there was this programme on called Something Else. All the other people in the room were watching Grandstand and football results and all of that, and I thought, ‘This is obviously something interesting,’ so I persuaded them to let me turn it over.

So we turned over to BBC2, and I’ve never seen a TV musical performance like it. We all know how difficult it is to get good music captured by a television studio. In this case, I don’t know what happened, but Ian Curtis’s performance and the band’s performance totally broke through the plastic of the medium. I think it was just the focusing of a really strong energy and catching the band on a good day, and then realising that this was a nationwide opportunity for them to get their ideas and their music across.

The extraordinary thing was, it was prime-time Saturday afternoon. I think it was about five thirty, five forty-five on a Saturday evening, so anybody could have been watching that, and anybody did in this room that I was in. All these old men who’d got cranky legs and hips suddenly were watching Joy Division instead of Dad’s Army. It was extraordinary, the effect that it had: there was none of the usual stuff – ‘Turn that rubbish over.’ I mean, people could obviously recognise that this was something quite unusual.

The way they chose to use their opportunity by starting off with ‘Transmission’ was quite significant, because the way that song builds is very modular and shows you the development that Joy Division had achieved in such a short period of time. Going from musicians who couldn’t even play their instruments, suddenly they were a supergroup. Steve’s drumming, Hooky’s bass guitar and Bernard’s guitar-playing were just extraordinary. It was the counterpoint.

Instead of wrapping themselves around the same melodies and configurations, each of them was reversing certain paradigms, so that Hooky, for example, becomes the lead guitarist. Bernard is then freed up to put all kinds of different shades on what a guitar could do, and he was using a lot of distortion and noise in quite a melodic way. The only other person I could think of who was doing that then was John McKay from Siouxsie and the Banshees. It was a very, very concentrated, focused ten minutes’ worth of TV time.

- 28 September 1979: the Factory I, Manchester

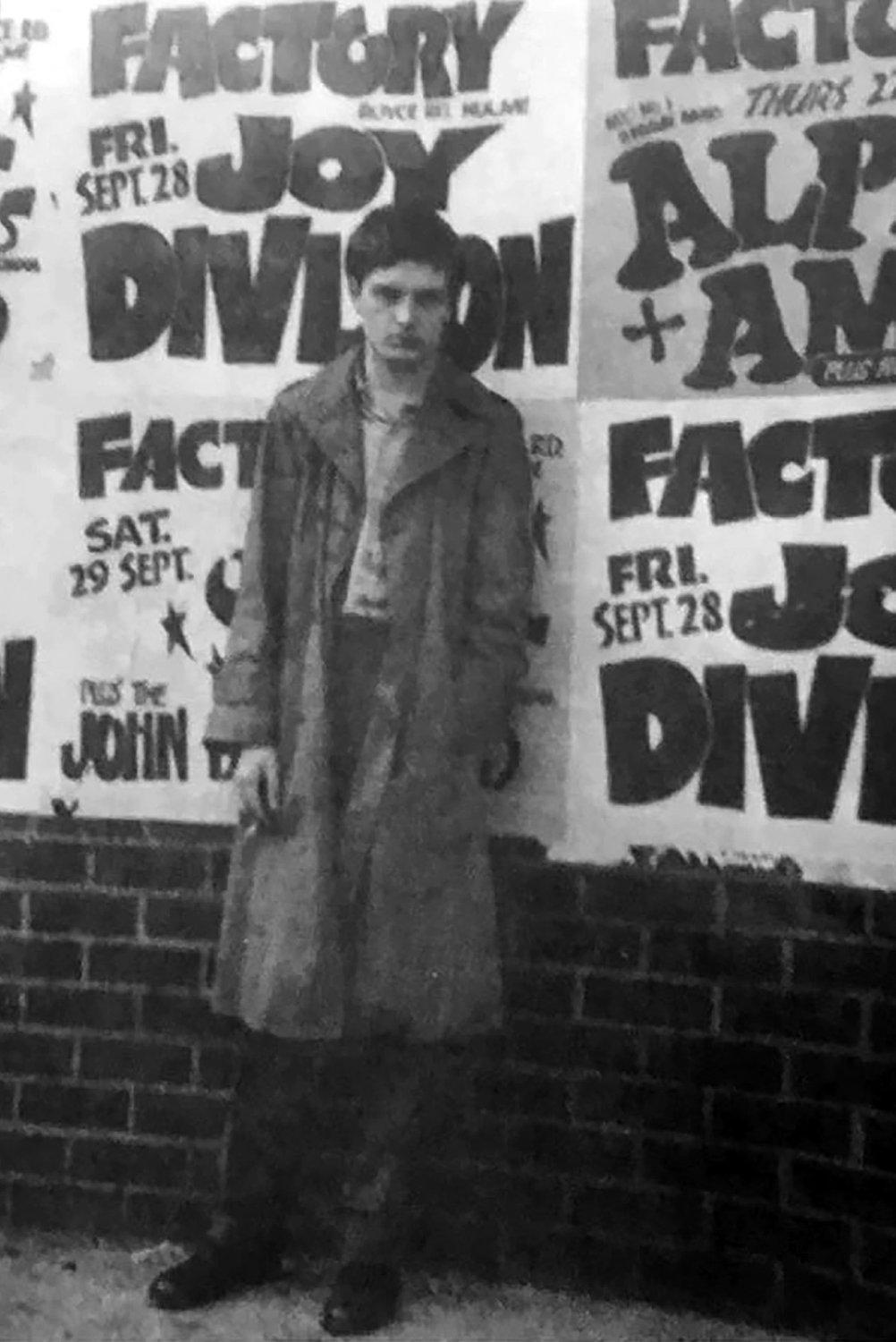

Deborah Curtis (from Touching from a Distance): As autumn approached they played The Factory for the last time before it closed down for an indefinite period, as the Russell Club’s licence had expired. It had been ‘our place’ for sixteen months and there was a feeling that we were about to begin the next chapter.

Paul Barrowford, joydiv.org: The lights were dim – Joy Division take to the stage and open with a new song called Atmosphere. The piece is slow, gothic, and features Ian Curtis on guitar. Four or five other songs are played the best being Colony, old favourites like Interzone, Wilderness and especially She’s Lost Control get the audience bopping frantically. 45 minutes later and a superb, controlled set is finished. The band return for Transmission, a false start, try again. At this point an incident occurs which spoils the whole evening.

Someone must have been having a go at bass player Peter Hook as halfway thru Transmission he starts attacking this unknown person with his bass. The incident continues with Hook chasing the person thru the audience and ends in a scuffle near the cloakroom. Hook returns to the stage and disappears into the dressing room. The band (minus Hook) continue with Step Inside and finish.

Ian Curtis outside the Factory, September 1979 (Phil Alderson)

Peter Hook: Me and Twinny took Bernard’s mate out to get him drunk – Dr Silk, he was a magician. And we took him out to get him drunk for a laugh, that’s what you did then. And he didn’t get drunk, so he must have rumbled what we were doing, putting vodkas in his tomato juice. He must have been doing it to us, because me and Twinny ended up legless. We got back to the Factory and we were just pissed, and when we played I was shouting at Steve all the time to play faster and faster, cos I was drunk.

We had a load of fans at the front; they’d be there at every gig. I remember this kid ran up to one of the fans, covered in badges, and grabbed him by the hair and nutted him on the back of the head. And I thought, ‘Oh, that’s not on.’ So I took me bass off and wielded it like Spartacus, and then the momentum – waaaaaaah – took me right offstage and I went right in the middle of them, and they fucking kicked the shit out of me basically, and then Twinny jumped in and grabbed me by the collar and pulled me to the back.

We grabbed this kid who we presumed was one of the protagonists, and me and Twinny were leathering him, and then we looked up and it was the kid with the badges on – we picked the wrong kid. The rest of the band played on, and it was my first example of when the band plays on really. So they didn’t help, the three of them, they just left me and Twinny to it. I remember afterwards I went fucking mad because they didn’t help me, they didn’t stop playing.

Bob Dickinson: You’d go to see a good band at that time, who would include Joy Division. You’d go because you had to get out of the house, because the house wasn’t usually a very nice place to stay. You’d go out because you’d see your mates, you’d go out because in the size of venues that we’re talking about that were in use at that time – like Rafters, Band on the Wall, the Russell Club, the Mayflower – there was a sense of intimacy with audiences, you could be very close to the band. It was more than intimacy; it was a sense of dialogue as well.

If you saw these bands, you could change them, and they could change you. You were there to echo what they would do, and they were there to echo what you were doing or saying. There was a lot more shouting: people shouted at the bands, and the bands would shout back at the audiences. I loved the way that there was always this dialogue. That said a lot about what the Manchester music scene was like: it was democratic because you were all involved.

Mary Harron, ‘Factory Records: Food for Thought’, Melody Maker, 29 September 1979

The songs are a series of disconnected images; Ian Curtis says he writes the lyrics to an imaginary film. The purpose of this surrealistic montage is not to convey a message, but to arouse strange feelings. One clue to Joy Division lies in their album’s title. Another is the description given by Martin Hannett, who calls them ‘dancing music, with gothic overtones’. Unintentionally, Bernard Albrecht gave an excellent description of ‘gothic’ in our interview, when describing his favourite film, Nosferatu. ‘The atmosphere is really evil, but you feel comfortable inside it.’

Mary Harron: Tony called me originally, and sent me a bunch of early Factory stuff. I still have the entire package. He’d read the stuff I’d written in Melody Maker about the Gang of Four and the Mekons, and that’s what sparked his interest. I think he had no idea that I was not British; he’d just read this stuff and was very taken with it, I guess because of the politics, and he was into the sixties radicalism. Anyway, he thought that I would appreciate Factory.

I went up with Steve Taylor from The Face, and Tony took us all around Manchester, and I did the interview with Joy Division. I think it was in a Chinese restaurant. Empty. And Tony is driving us around, talking a mile a minute – it was basically a Tony monologue. Then we went to see the producer, Martin Hannett. We saw Orchestral Manoeuvres and interviewed those two guys, and they played me something, I think on a cassette: this electronic pop music, which was new, and which I loved.

I don’t think I met Peter Saville then, I met him later. Or maybe I did, and then later met him again at a show in London and got to be friends with him. He had tons of interesting ideas. We talked for about six hours the first time, all about what was happening after punk. Obviously I was very into the Warhol Factory, but I think what I loved most about Factory at that point was the incredible visuals, the style and the theory. The ideas behind it.

It was the most original idea for a record company I think I’d ever seen. I was into the idea of it being a little label with a complete identity, every aspect of it being designed and created within an overall aesthetic. I thought it was incredible, the idea of creating in a non-corporate way. It was not major-label, but they were into manufacturing. And there was nothing as beautiful as what Peter was making.

I was still hungover from punk. And the one new thing I’d got into was Gang of Four and the Mekons. Musically, I did not appreciate Joy Division as much as I did later. I don’t know why I wasn’t more overwhelmed, because I think they’re great now. I don’t know why I didn’t think more of them, but when I first saw Eraserhead, I didn’t like it. I think it was too new, I needed more time to appreciate it. The music was very different. What did it relate to? I think I was still into a punk aesthetic that was very tight and disciplined.

I saw them in London, at one of those weird west London pub things; it might have been the Nashville. When I did the interview, they were so nice and smart and innocent. Very bright, I guess working-class Manchester kids, and yet they were serious and innocent and modest, but they had all their ideas about having this life making music. I didn’t see any disharmony in them. There were bands that were aggressive towards me, and I didn’t get any of that from them. They were not shy exactly, but introspective. Very thoughtful. They were lovely.

Mary Harron, ‘Factory Records: Food for Thought’, Melody Maker, 29 September 1979

History never repeats exactly. But there is one important parallel here: apart from the Distractions, all the Factory groups have turned away from daily life, towards what in the Sixties would have been termed ‘inner space’. What the Sixties groups achieved was no more than what Joy Division achieve – a series of thrilling sensations. But because this exploration was done through drugs, they thought they were discovering cosmic truths. Without drugs, today’s explorations are private and bewildered, which at least is honest.

Mary Harron: I think I got a lot of it wrong in that article. I felt that I should have listened harder. The other thing was, Tony was pushing them so hard, I resisted. I felt I was being a bit steamrolled, and I was going to be more critical. We were trying to preserve our integrity as outside voices, which nowadays I don’t take so seriously. That was the error of rock journalism: that no one should sway my opinion.

But Tony was pushing so hard about giving acid to everybody, a psychedelic revolution in consciousness. As I was anti-hippie in that sense, I thought it was a really bad idea. He was going a mile a minute – it was linked in with Marxism, and with anarchy, and psychedelic revolution – and when he got into giving out acid, I was thinking, ‘That’s going to be terrible.’ And I guess in the end drugs did bring it all down, but it wasn’t acid.

At the time, I’d never met somebody with such a total vision – for a place, for creating a social revolution. He had a great description of Malcolm and the Sex Pistols. He said nobody realised that what Malcolm was trying to create when he made the Sex Pistols was the Bay City Rollers of outrage. He didn’t intend for the music to be serious. At the time, what he was saying about what he was going to do in Manchester – in a way, he kind of did do it. I think he thought he could create more of a change in consciousness, a psychic revolution.

Tony Wilson: I remember Mary Harron, the reviewer and writer, came to Manchester one night. I think we were in a restaurant, about three or four in the morning. I remember she was saying, ‘But are you sure there’s more?’ And I said, ‘I believe there is.’ If you look at the lyrics to ‘Shadowplay’ – ‘I let them do everything they wanted to’ – there was a complexity in those lyrics which, I said to her, ‘I believe that points the way to more complexity of emotion and of expression.’ And I was right.

I give Bernard the credit for this thought, which is that punk enabled you to say ‘Fuck you’, but somehow it couldn’t go any further. It was just a single, venomous, two-syllable phrase of anger which was necessary to reignite rock’n’roll, but sooner or later someone was going to want to say more than ‘Fuck you’. Someone was going to want to say ‘I’m fucked’, and it was Joy Division who were the first band to do that, to use the energy and simplicity of punk to express more complex emotions.