Thoughts on material expressions of cultic practice. Standing stone monuments of the Early Bronze Age in the southern Levant

Introduction

Defining the sacred and approaching the archaeology of religion is not an easy feat. Therefore the aim of this article is not to make concluding statements on the nature of religion and belief as a phenomenon.1 Rather it seeks to investigate the potential diversity of this phenomenon, as seen from archaeological remains in the EBA period of the southern Levant and hopefully ignite a discussion concerning the importance of smaller sites and structures unconnected to settlements.

In the southern Levant small and seemingly isolated sites are scattered throughout the countryside. Along with areas of activity located at the periphery of walled settlements, these sites might be easily overlooked or inadequately understood by archaeologists, but they form a complex system of sites of different sizes and functions supporting the walled settlements of the region. In order to better understand the workings of the EBA societies these sites should be considered in a larger framework. In this paper it is the archaeological material offered by standing stone sites in the central southern Levant that form the basis of enquiry and interpretations.

These interpretations are intended to offer a dynamic impression of how standing stone sites were incorporated into a wider societal context. It is argued that the cultic practices of the EBA could have consisted of both highly formalised and less formalised customs, the diversity of which is not sufficiently recognised in the archaeological record. This analysis developed from an interest in the relationship of ancient humans to the landscape in terms of movement and use of areas outside walled settlements. Furthermore, the explanatory framework of heterarchy has been considered a basic premise in order to understand the diverse nature of archaeological sites (Crumley 1995).

Historical framework of the EBA period in the southern Levant

The EBA period of the southern Levant had formerly been defined by a marked transition from the previous Chalcolithic period. Today the transition between the two periods is seen as a more gradual development (Kerner 2008, 157). The period is characterised by the appearance of walled settlements, which were most likely central places for the collection and storage of agricultural products (Philip 2008, 182). There was an intensification of practices, such as irrigation agriculture and cultivation of tree crops. Animals, such as donkeys and oxen, were increasingly used for transport and as draught animals. Tools made from metal became more common. While none of the above mentioned practices were novel technologies, they were employed more efficiently resulting in changes in the basic economy (Philip 2008, 179). In the EBA trade was conducted on a wider scale, with the movement of both goods and people, tying the regions of the southern Levant together in intricate webs of interactions (Philip 2008, 193). Trade was also conducted with more distant regions including Egypt, which might have imported goods such as fine oils and resins (Philip 2008, 182; Greenberg and Eisenberg 2002, 220). The nature of the socio-political organisation in the EBA has been debated and several scholars have found the traditional explanation of a socio-political organisation based on a city state concept invalid in relation to the walled communities of the period (Chesson 2003; Chesson and Philip 2003; Philip 2003; 2008). Instead the distinct material evidence of the EBA is explained as signifying a socio-political organisation based on staple finance strategies with elites investing their efforts in communal projects and in controlling agricultural produce (Chesson and Philip 2003, 9; Philip 2008, 166). This would explain the lack of evidence for conspicuous consumption and of marked social stratification usually indicated by elite housing and elite burials (Chesson 2003, 86; Philip 2008, 163).

Cultic practices of the EBA period in the southern Levant

Before turning to the discussion of the cultic significance of standing stone monuments the general evidence of cult in the EBA warrants some concern.

The reconstruction of ancient human daily life is difficult at best. As archaeologists we only catch a glimpse of this through architecture, objects and human remains. The reconstruction of ancient belief systems and cultic activities does not avoid this complexity and there are limitations when attempting to study belief systems and rituals of the EBA. There are no contemporary textual sources which can provide clues to the cultic practices of the period. Iconographic material is rare and consists of seals and seal impressions with motifs interpreted as scenes of cultic activity. The motifs represent people engaged in a ritual dance and human figures, one possibly dressed as a horned animal, standing next to buildings interpreted as cultic structures (Ben-Tor 1977, 94, 96; 1992, 155; Lapp 2003, 543). Due to the schematic nature of the iconographic depictions their meaning is difficult to deduce. Sculptural material includes different types of figurines. Most commonly these are zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figurines and composite figurines represented by laden figurines (donkeys carrying baskets) and riding figurines (donkeys ridden by a human figure) (Al Ajlouny, Douglas and Khrisat 2011, 93, 96).2 The cultic significance of these figurines has been indicated by their find contexts in cultic structures and in burials excluding them as more secular objects such as toys and teaching aids. Finds of figurines in domestic houses have been suggested as representing evidence of domestic cults (Al Ajlouny, Douglas and Khrisat 2011, 98–102, 109–110).

Arenas of cultic practices found inside the walled settlements of the EBA period are traditionally identified by broadroom structures set apart from domestic architecture, often located within courtyards or enclosures. These courtyards or enclosure spaces often contain stone platforms interpreted as altars. The broadroom structures are relatively small architectural units with wooden posts for roof supports built on stone bases. At a number of settlements larger cultic compounds are found with multiple broadroom structures occurring close together (Philip 2008, 173).3 It has been stated by scholars that the finds located inside cultic structures appear to be less distinctive in the EBA and that cultic paraphernalia of the period are generally ill defined (Philip 2008, 174; Genz 2010, 47, 49). It could suggest that cultic paraphernalia did not consist of “fixed” assemblages of items, but that they could vary possibly from place to place and from time to time.

Standing stone monuments of the EBA southern Levant

Definition and distribution

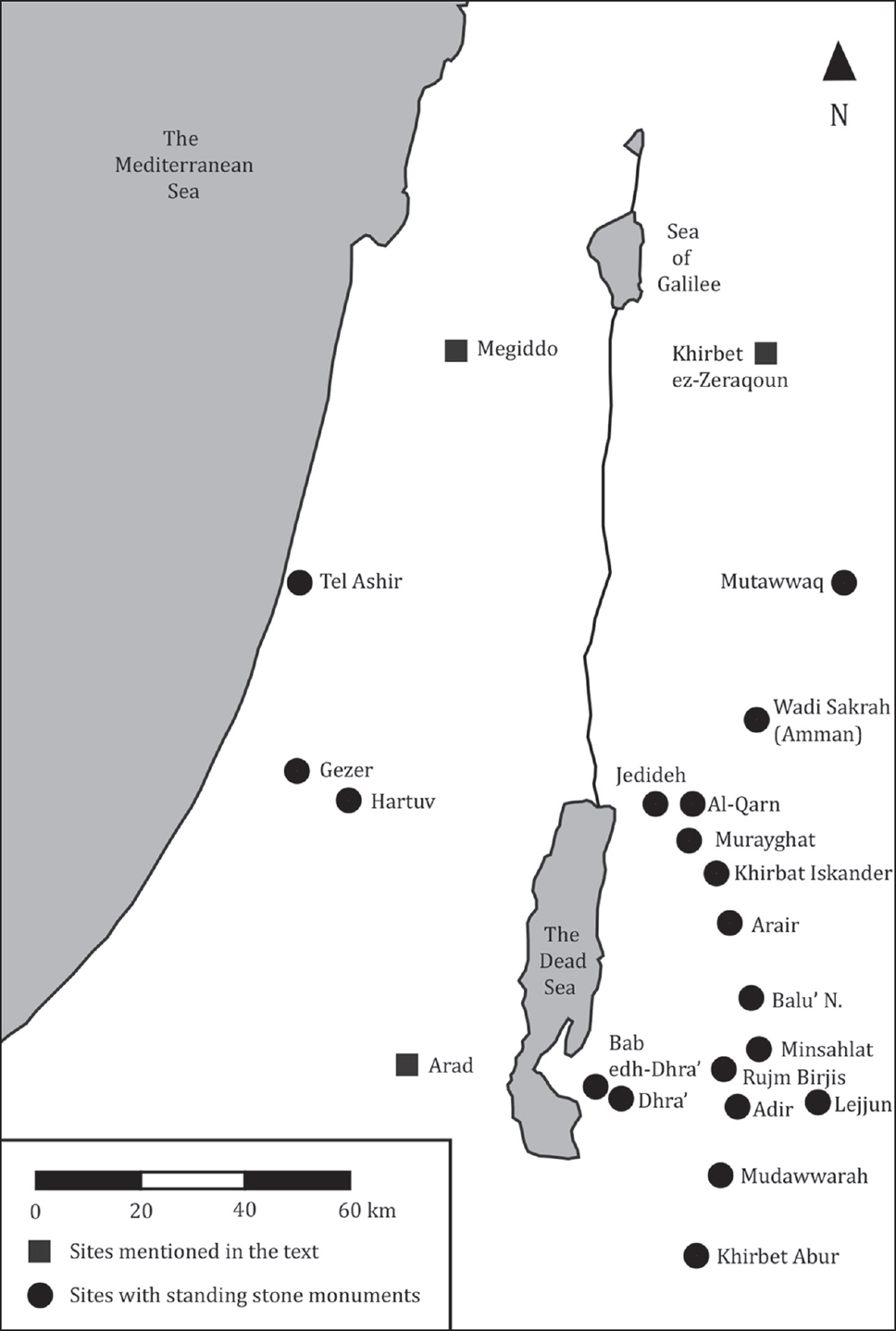

Standing stone monuments can be broadly defined as structures consisting of one or more upright stone slabs deliberately raised and placed in the landscape by humans. As a category of monuments standing stones are not a uniform phenomenon. They appear in different sizes, numbers and configurations. So far nineteen standing stone sites belonging to the EBA have been located in the central part of the southern Levant (Andersson 2011) (see Fig. 5.1).4 Only seven of the nineteen sites have been investigated by excavation. These include the monuments at Dhra’, Gezer, Hartuv, Khirbat Iskander, Mutawwaq, Tel Ashir and Wadi Sakrah. The majority of chronological assessments of the sites has been made by ceramic evidence recovered from surveys or by the indirect evidence provided by the proximity of the monuments to other EBA remains (Andersson 2011, 71). The standing stone sites can be roughly divided into four groups based on the relation of the stone monuments to other archaeological evidence. One group consists of open air standing stone monuments not immediately associated with settlements or other substantial archaeological remains (i.e. dolmen fields, high concentrations of cairns, stone lines etc.).5 Open-air monuments associated with settlements represent a second group.6 A third group are standing stones located within architectural units inside settlements.7 The last group consists of standing stones associated with significant dolmen fields, cairns and stone lines.8

The physical properties of the monuments do not appear standardised, but a general description can be given. The monuments are usually made from undressed stone, which appears to have been only modestly worked.9 The height of the monuments can vary considerably, but in the central southern Levant the monuments are generally recognised as being 1–5 m in height (Andersson 2011, tables 44 and 45).10 The monuments can be found in different arrangements, which can consist of a single freestanding stone slab or of multiple stones placed together, commonly forming a line of monuments. The number of stone slabs in the multiple arrangements of stones varies with as many as 17 slabs set up in a line (Jones 2006, 317; 2007b 124).

It is not known if the distribution of the monuments in the central part of the southern Levant as seen today is an expression of their original distribution or if it is a result of diverse rates of land-use in the different regions (Philip 2008, 173). Today, the distribution of the sites shows a cluster east of the Dead Sea (Fig. 5.1). Towards north the numbers appear to be significantly lower, which has been connected to a more intensive agricultural use of the region (Palumbo 1998, 104). Towards south, in the Negev and the Sinai, the monuments seem to be especially well represented (Avner 2002, 65).11 With the significant number of monuments located in the south it might be speculated that more of these monuments would originally have been in existence in the central part of the southern Levant. Alternatively, the higher distribution of monuments in the south, as seen today, could suggest that the cultic traditions related to these monuments were practiced more in these regions. Today the monuments of the central southern Levant are influenced by modern development of land resources or other forms of human impact leading to their destruction and thus the opportunity to study them in this region is rapidly diminishing.12

Advancing a definition of the sacred nature of standing stones

Besides the traditionally identified broadroom structures inside settlements the EBA cultic landscape probably incorporated a variety of places where cult could be practiced. Philip has emphasised the diversity of cultic locations known from the EBA as an indication of “… the simultaneous existence of multiple spheres of cult activity, not all of which would have been equally well integrated with systems of political control.” (Philip 2008, 173). The proposal of the simultaneous existence of multiple spheres of cult activity is an appealing approach, when considering the possible diversity of cultic behaviour and their settings.

The wide distribution of a seemingly standardised plan of cultic structures found within settlements points to cultic activities in formalised settings, while the existence of domestic or private cults has been argued based on the findings of figurines in domestic contexts (Al Ajlouny, Douglas and Khrisat 2011, 109–110). These settings are located within settlements, which were unmistakably centres of intense human activity. In the past archaeological investigations have tended to concentrate efforts on larger settlements resulting in the walled settlements of the period appearing as solitary ‘islands’ in the landscape. However, human activity also took place outside the walled settlements and there is little reason to think that this did not include cultic practices. Standing stones are one type of monuments appearing prominently in the landscape sometimes unrelated to a settlement. Even though they appear as conspicuous features there might be no explicit reason to argue that these monuments were related to cultic activities. However, a conceptual bridge between open-air sites with standing stones, as cultic arenas, and structures traditionally identified as having a cultic function can be proposed. The connection is indicated by the identification of standing stones built into broadroom structures or located within complexes of broadroom structures. This is a feature that has been suggested at Hartuv (EB I) and at the large cultic centre, Mutawwaq (EB I) (Mazar and Miroschedji 1996, 11; Fernández-Tresguerres Velasco 2011, 114; Sala 2011, 6–7). At Hartuv the standing stone line build into the southern wall of hall 152 was interpreted as originally being a freestanding stone line that was later incorporated into the cultic structure constructed at the site, as part of a larger building complex (Mazar and Miroschedji 1996, 11). At the site of Mutawwaq a standing stone has been identified inside the cultic compound consisting of three main structures, five auxiliary buildings and a courtyard. The standing stone is located in the courtyard at the northeastern wall of the enclosure surrounding the complex. (Fernández-Tresguerres Velasco 2011, 114). Although only the two examples of Hartuv and Mutawwaq have been discovered so far, the merging of cultic structures or compounds and standing stones appears as a significant connection between the two architectural types (Philip 2008, 173). This physical link indicates a cognitive link, thus demonstrating the cultic significance of standing stones.

By ethnographic accounts and even contemporary examples the practice of any belief system can vary within a society, thus stating that any given belief system remains static and unchanging is inadequate. Highly formalised traditions may exist alongside less formal customs and the two might be practiced in different settings. Additionally, rituals can be performed at different intervals, some frequently and some rarely. This scenario is valid for contemporary and ancient cultic practices alike. Therefore, the practice of the sacred as a defined phenomenon may consist of a variety of cultic behaviours manifesting themselves in a multitude of different ways within a society and in the archaeological record. This of course is a challenge for the archaeologist, for whom standardised or large-scale manifestations of cult might be easier to detect than the more subtle expressions. A diversity of localities stretching from small-scale constructions to big architectural manifestations may be envisioned, and one might tentatively draw a comparison to the varieties of cultic arenas known from contemporary practices such as house altars, roadside shrines, village churches and cathedrals. Cultic arenas of different scale might have been more or less integrated into formal systems and would have existed in the landscape beyond the walls of settlements.

The Dhra’ standing stone monument

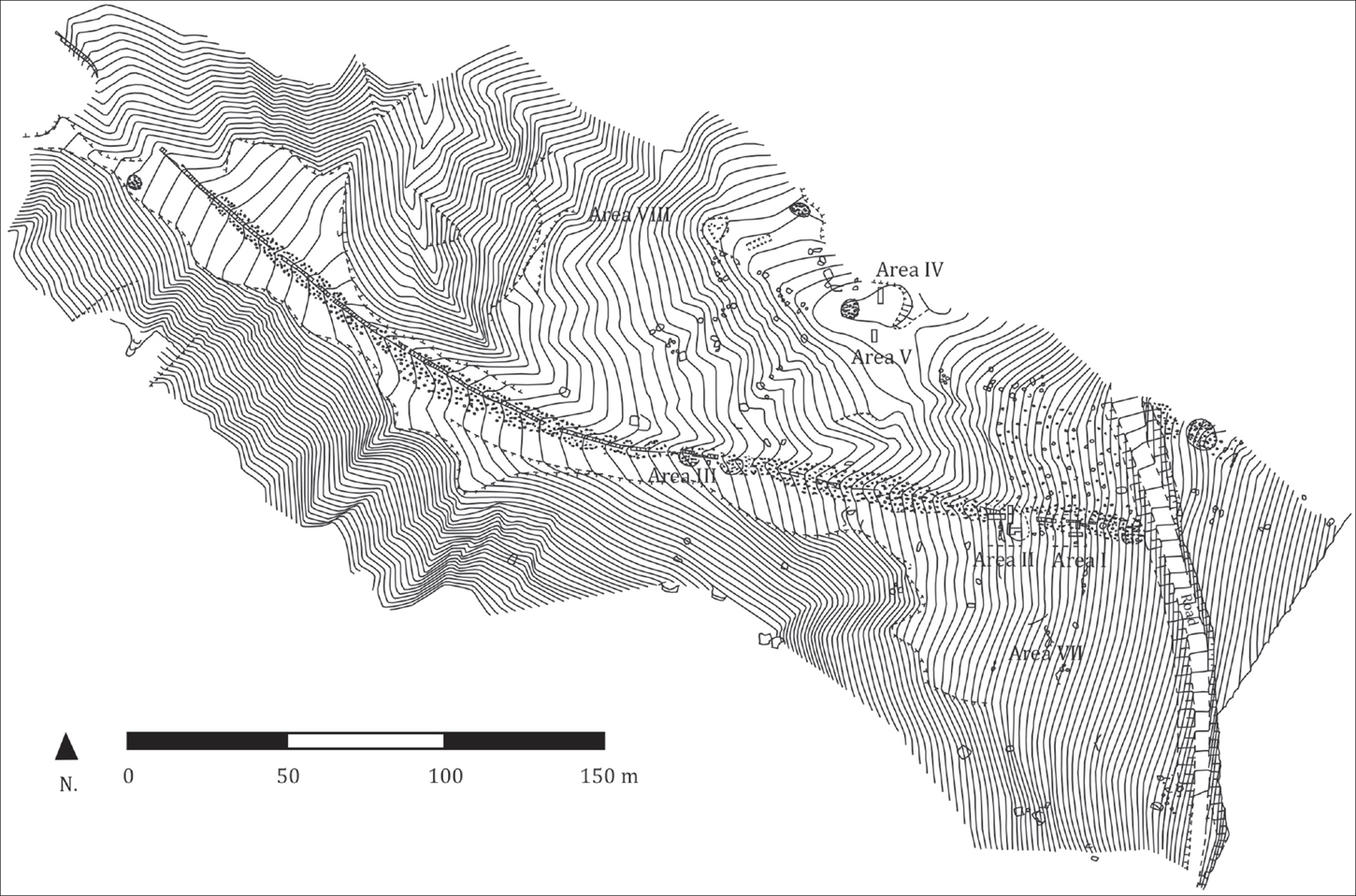

The site of Dhra’ is located in modern day Jordan in the southern Ghors. Dhra’ is flanked on one side by the Dead Sea Plain and the Lisan Peninsula (towards west) and on the other by the escarpment to the Kerak Plateau (towards east). The well-known EBA I–IV site of Bab edh-Dhra’ lies 4.5 km towards west in a straight line.13 The site is situated c. 500 m south of the southern bank of Wadi Adh-Dhra’, a tributary of the principal watercourse of the area, the Wadi al-Kerak. Situated on a hill ridge, the site was identified during a survey campaign and was excavated in 1992 and 1994 by an archaeological project directed by Carsten Körber, who was at the time assistant director at the German Protestant Institute of Amman (GPIA) (Körber 1993; 1994a; 1994b; 1995).14 The project was a small-scale excavation concentrating on the architectural features of a standing stone and a wall (Fig. 5.2). Eight areas were investigated at the site (Areas I–VIII).

Area II contained the standing stone monument situated on a stone platform (Fig. 5.2). The standing stone itself is made from a locally available slab of stone, which is only roughly worked, standing at a maximum height of 2.90 m above ground, with a width of 3.30 m at ground level, inclining towards the top of the stone slab to a width of 1.70 m when approached from a western direction. The stone monument has a breadth of 1 m and reaches a depth of approximately 1 m into the ground (Körber 1993). A semicircular cell of stones one course high, uncovered during excavation, indicated the western face of the standing stone as the front face of the monument.15 The excavation also disclosed the presence of two subsidiary standing stones, one on either side of the main monument. These measured c. 60 cm in height, 40 cm in width and 20 cm in breadth. The stone platform was traced on the long side facing west for 9–10 m at a height of 70 cm. Although it was not possible to expose the stone platform in its full extent, it was reconstructed as originally being a rectangular structure (Körber 1993, 551–552) (Fig. 5.3).

The site of Dhra’ was furthermore characterised by a number of other archaeological features, such as a wall construction and four cairns located in the immediate vicinity (see Fig. 5.2). The wall was traced for approximately 400 m running along the contours of the hill ridge on an east–west axis, with a slight bend towards north in the eastern part. It was not possible to suggest the original extent of the wall. Like the platform, it was constructed from locally available stone and was preserved to a height of 70 cm and was 1.60 m wide with up to five courses of stone still standing at the time of excavation (Körber 1994b, 70). EB IA sherds were found in relation to the wall in Area I. Unfortunately the specific find context for the sherds is not known and therefore the evidence could not indicate the date of construction for the wall (Andersson 2011, 77). A dating for the four cairns at the site can not be suggested since they were not investigated.

Fig. 5.2: Topographical map of Dhra’ with the locations of Area I–VIII (Andersson 2011).

Fig. 5.3: View of the Dhra’ standing stone from an eastern direction showing the front face of the monument and the stone platform (courtesy of Hugo Gajus Scheltema).

A relative sequence of construction was established for the architectural features identified in Area II and the wall structure (Area I and III). The standing stone was erected first, perhaps initially as a freestanding monument, with the later addition of the surrounding stone platform and possibly at the same time the semicircular cell in front of the stone monument. The subsidiary standing stones were then added on either side of the larger standing stone. Lastly, the east–west running wall was built at the site (Andersson 2011, 16).

Despite the initial hypothesis of the standing stone being related to a burial (Körber 1993, 551; 1994b, 72) subsequent excavations did not confirm this. Although there is lack of substantial evidence of a permanent EBA settlement,16 it is clear that effort and labour was put into the construction of the standing stone monument, its platform and the wall. Thus it can be assumed that the site was of importance for the people who built it and made use of it.

Finds from Dhra’

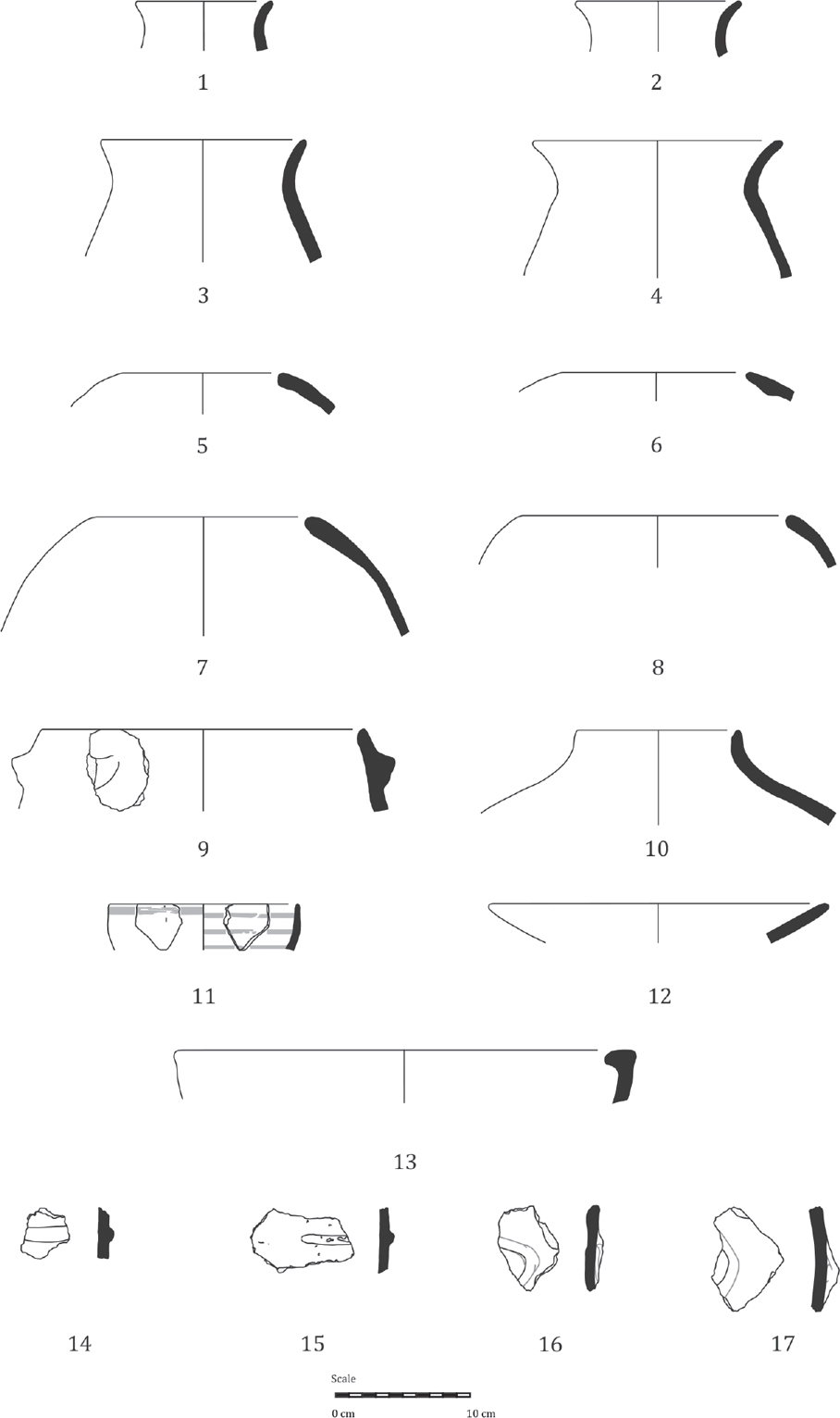

The finds recovered during the excavation included ceramics, two stone pestles, a grinder and flint tools. Only the ceramics have been subjected to study (Andersson 2011). A high proportion of small to large necked jars characterised the ceramic assemblage along with small to large holemouth vessels (Fig. 5.4, 1–10). Other types such as plates, small bowls and vats are poorly represented (Fig. 5.4, 11–13). The functional interpretation of the assemblage thus points to an emphasis on storage of liquid and/or dry goods and possibly aspects of food preparation (Andersson 2011, 50). The distribution of ceramics in the respective areas demonstrated that the area centred on the standing stone had one of the highest proportions of ceramics at the site.17 This suggests that the area was a place of more intensive use compared to the other areas. Furthermore, the ceramic assemblage showed a higher degree of variation in vessel types along with a differing functional composition. Like other areas, area II had a high proportion of vessel types related to liquid and dry storage (jars and holemouth types). The anomaly compared to other areas existed in the presence of several plate and bowl types suitable for functions connected to presenting, serving or eating of foodstuffs (Andersson 2011, 77). Other interesting features of the Dhra’ assemblage included a few pieces of plastic decoration (Fig. 5.4, 14–17). These could be examples figurative decoration in the form of snake applications, but the small sherd samples make this identification somewhat tentative. Snake applications are considered to be a type of cultic iconography connected to the belief system of the EBA and are represented at sites like at the cultic structure at Mutawwaq (EB I) and at Khirbet ez-Zeraqoun (EB II–III) (Genz 2010, 49; Sala 2011, 7, fig. 7; Al Ajlouny, Douglas and Khrisat 2011, 101, 106–107, table 2). Based on the fabric analysis of the ceramics from Dhra’ it is most likely that the plastic decoration belonged to holemouth jars and less likely to necked jars (Andersson 2011, 63, tables 22 and 23). Although some vessel forms of the assemblage were too generic to firmly place them in one or the other sub period of the EBA, many characteristic features of the ceramic assemblage indicated a dating of the material to the EB I period (Andersson 2011, 66). Even though the additional find groups have not been subject to detailed study the presence of two stone pestles (Area II and VIII), a grinder (area II) and an undefined amount of flint material (Area II, IV, V, VI, VII and VIII) indicate that the site was the location of a variety of human activities. The pestle and the grinder found in Area II are noticeable, stressing aspects of food processing activities.18

Fig. 5.4: Selection of the ceramic assemblage from Dhra’. 1–4: small to large necked jars. 5–10: small to large holemouth jars and a holemouth jar with an everted rim. 11–13: a small bowl, a plate and a vat. 14–17: plastic decoration (Andersson 2011).

In sum the evidence suggests a locality with remnants of temporary occupation dating to the EB I. The ceramic assemblage of the area suggests that people performed activities such as cooking and storing of goods for shorter or longer periods of time. The evidence of these activities might at first hand appear to represent common practices of daily life. However, if it is accepted that everyday objects could be incorporated into cultic activities, it can be suggested that at least the material evidence recovered from the immediate area around the standing stone was part of ritual activities. The ceramics and stone tools found in Area II might represent offerings placed at the standing stone. They could also be connected to preparation of foodstuffs, perhaps offerings, in the vicinity of the stone monument.

The diverse appearance of standing stone sites in the southern Levant – markers of a common concept?

A cognitive link between standing stones at sites of very different physical nature is suggested here. The monuments appear as a diverse group due to the variability in the numbers and arrangements of the monuments, the size of the site where they occur and the additional archaeological features found in their vicinity. Yet it is proposed that the people visiting these sites and viewing the standing stones would have connected them to a common conceptual theme. Despite the diverse context of standing stones presented above, their setting point towards cultic purposes. However, with the cultic framework and belief system of the EBA not being clearly understood yet, no closer definition can be given here.

Standing stones may represent less formalised arenas of cultic practice or places connected to different kinds of cultural practices compared to the traditionally identified cultic structures inside settlements. The existence of large sites such as Murayghat and Jedideh, unconnected with settlements has been interpreted as ceremonial landscapes. The site of Murayghat has a collection of megalithic structures and an extensive dolmen field with a prominent standing stone (the hajr mansub) (Savage 2010; Savage and Rollefson 2001, 225). At Jedideh standing stone monuments are associated with dolmens and stone lines making up a landscape, which has been suggested as having a ceremonial function (Mortensen and Thuesen 1998, 96). It might be suggested that while many settlements had their own arenas of cultic practice, these sites, unconnected to settlement, could have acted as major cultic centres and gathering places for a number of communities, perhaps with gatherings occurring at intervals.

How the standing stone monuments found near settlements relate to the formalised cultic settings (represented by cultic structures) inside settlements is poorly understood due to their disappearance from the archaeological record since first reported or due to the lack of excavation. Of the monuments found on the outskirts of EBA settlements, only the examples at Khirbat Iskander have been subjected to archaeological investigations and the results of these are not yet published.19 At Mutawwaq, a standing stone has been found associated with a cultic complex. Additionally, three other standing stones are found at the site, one in an open space enclosed by a wall and two on a mound overlooking the village. Mutawwaq has been suggested as a major cultic centre for settlements in its vicinity (Fernández-Tresguerres Velasco 2011; Sala 2011, 6–7). Despite the general lack of excavation what might be reasoned from the context of the monuments found in the vicinity of settlements is that a relationship existed between the settlements and the standing stone monuments found on their outskirts. They likely represent areas used by the inhabitants of the EBA communities. The small size of traditionally identified cultic structures inside settlements could suggest that there was restricted access to these buildings and that only small segments of the population could participate in the practices within the cultic buildings at one time (Genz 2010, 48). Open-air sites close to habitation could have been cultic gathering points for larger groups of people.

New attitudes towards the landscape: movement, trade and travel

The site of Dhra’ is not associated with a settlement and it does not seem to have been part of a larger cultic landscape. The site is situated at a tributary to the Wadi al-Kerak, just at the escarpment to the Kerak plateau. Other reasons might explain the seemingly isolated nature of the Dhra’ standing stone monument. The EBA was characterised by changes in attitude towards the landscape. The long-term investments made in certain plots of land as people inhabited walled settlements and were involved in intensified agricultural practices, might have prompted increased feelings of territoriality. However, life was not confined to the immediate surroundings of walled settlements as people moved within the landscape, to travel and to conduct trade.

The major route making travel possible from the Dead Sea plain region to the Kerak plateau would have been the Wadi al-Kerak and by implication its tributary the Wadi-adh Dhra’, by which the site of Dhra’ is located (Miller 1991, 1). While movements in the landscape such as travel from one destination to another might not leave much evidence behind in the archaeological record, trade is often easier to detect, from the remains of traded goods. Indirect evidence from Bab edh-Dhra’ suggests that this site and its surroundings were facilitating trade and travel. A high proportion of donkey remains at the site (EB I–III) indicates that it could have been a large station of trade tied into exchange networks (Milevski 2011, 191, table 10.1). The Wadi el-Kerak route would likely have linked the Dead Sea plain and the Kerak plateau. Savage finds it tempting to suggest that a trade route connecting Bab edh-Dhra’ towards west with Arad and towards east with the EB sites of the Kerak plateau would have existed in the EB I (Savage 2012). Likewise, Yekutieli has noted the connections towards east between the southern coastal plain and the Dead Sea region (EB IA), which would have been the place where bitumen originated. Bitumen has been discovered at several southern coastal plain sites (Yekutieli 2001, 676). The same route has been suggested by Milevski (Milevski 2011, 169). This recounts the indirect evidence of the possible movement through the region encouraged by trade. It suggests that Bab edh-Dhra’ and its immediate vicinity was a node facilitating regular movements of people and commodities east towards the Kerak plateau and west past the Arad plain towards the southern coastal plain reaching the Shephelah.

The topographical features encouraged travel and trade along the Wadi al-Kerak, where the site of Dhra’ can be found and the site is placed at a liminal location just before the escarpment to the Kerak plateau. The Dhra’ standing stone has been interpreted as having a cultic purpose, which is supported by the general connection between standing stone monuments and arenas of cultic significance in the southern Levant. In this larger framework of cult and trade the Dhra’ monument, a site seemingly isolated from settlements or larger cultic landscapes, but located at an important route of travel, might have tied into an extended network of movement in the countryside as a kind of cultic way station, perhaps with a function comparable to that of a roadside shrine. The ceramic assemblage found in the vicinity of the standing stone monument indicates some elements of the cultic practices performed at the site with possible offerings placed at the monument in different types of ceramic vessels. Some aspects of food processing, either symbolic or real, is indicated by the presence of pestles. The evidence from the other areas signifies the temporary occupation, which people set up at the site, where food processing and storage of goods took place.

Conclusion

Standing stones of the EBA period in the central southern Levant present themselves as a diverse group of monuments. However, their cultic significance is indicated by the cognitive connection between standing stones, open-air sites and cultic structures and compounds. It is further corroborated by the existence of these stone monuments at sites interpreted as ceremonial landscapes. Many of the monuments are found related to walled settlements, which suggest that the monuments were an integral part of the cultic milieu of the EBA. The question remains of how these related to more formalised practices at cultic structures inside the settlements and what kind of practices were performed at the monuments? In general the standing stone sites of the EBA in the south central Levant represent a constituent of the cultic landscape that is not well understood. Nevertheless, the distribution of the stone monuments, whether appearing as isolated monuments, being located in the proximity of settlements, funerary structures or stone lines or appearing inside cultic structures or complexes, indicates a widespread tradition. It is plausible that the people of the EBA would have had a shared awareness of their function and of their symbolic meaning. The site of Dhra’, with its small size, evidence of temporary occupation and its location at a route of travel, represents a stopping point along a frequently travelled route with a cultic element in the form of a standing stone monument. As such Dhra’ is an expression of the less easily recognised sites of the archaeological record and adds to the understanding of cultic practices of the EBA.

Notes

1 The phenomenon of religion, belief and cult has been advanced from a broad range of theoretical perspectives and methodological approaches, throughout the history of archaeological study. The different standpoints will not elaborated here, but see for instance Insoll 2004, 1–100; Renfrew 1994, 47–54 and Steadman 2009, 21–35.

2 For a comprehensive overview of the distribution of figurines in the EBA see (Al Ajlouny, Douglas and Khrisat 2011, tables 3 and 4).

3 See for instance the EB II–III cultic compounds at Khirbet ez-Zeraqoun and Megiddo, consisting of multiple broadroom structures (Philip 2008, 173; Genz 2010, 47–49).

4 The EBA has been chosen as a focus in this paper, disregarding examples, which are firmly dated to other periods or monuments, which could not be dated.

5 Adir (Chesson et al. 2005, 10, 20, Miller et al. 1991, 96–98), Dhra’ (Andersson 2011; Körber 1993; 1994a; 1994b; 1995), Gezer (Ben-Ami 2008), Khirbet Abur (MacDonald et al. 2004, 326; Scheltema 2008, 59), Tel Ashir (Gophna and Ayalon 2004), Wadi Sakrah (Scheltema 2008, 84; Abu Shmais and Scheltema 2011; Scheltema 2011). The Adir and Wadi Sakrah examples are located within modern settlement (Adir and Amman, respectively), which might conceal their original context (i.e. possibly located in or near EBA settlements). The Gezer monuments are traditionally dated to the Middle Bronze Age II, but a reanalysis of the stratigraphy of the site by Ben-Ami dated the erection of the monuments to the EB II or III (Ben-Ami 2008, 26–27).

6 Al-Qarn (Palumbo 1998, 103–104; Savage and Rollefson 2001, 222–223, fig. 3; Savage 2010, 36), Arair (Ben-Ami 2008, 19–20;, Schick 1879, 191), Bab edh-Dhra’ (Albright 1924, 6, 10; Albright 1926, 58–59; Philip 2008, 173), Balu’ North (Miller et al. 1991, 41–43), Khirbat Iskander (Glueck 1939, 127–129, fig. 48; Richard and Boraas 1984, 64, fig. 5; Richard 2010, 8, 10; Richard and Long jr. 2006, 274; 2007, 270–271; D’Angelo 2010, 209–210), Lejjun (Chesson et al. 2005, 20, 24–25; Jones 2006; 2007a; 2007b), Minsahlat (Chesson et al. 2005, 19–20; Miller et al. 1991, 63), Mudawwarah (Chesson et al. 2005, 10, fig.1, 25; Miller et al. 1991, 145), Mutawwaq (Fernández-Tresguerres Velasco 2011, 113–119), Rujm Birjis (Miller et al. 1991, 55–57, Chesson et al. 2005, 12–13, fig. 3).

7 Hartuv (Mazar and Miroschedji 1996, 7–9, 11–12) and Mutawwaq (Nigro, Sala and Polcaro 2008, 220–222, 227; Scheltema 2008, 73–75; Fernández-Tresguerres Velasco 2011, 113–114).

8 Jedideh (Mortensen and Thuesen 1998, 96) and Murayghat (Savage 2010; Savage and Rollefson 2001).

9 Exceptions do exist in the examples from Murayghat (the hajr Mansub) and Gezer. These standing stones are characterized by incised grooves and cupmarks (Ben-Ami 2008, 23, fig 4; Savage 2010, 36, fig 4).

10 Some scholars have identified standing stones as low as 10 or 30 cm in height. These would be hard to detect individually and have been identified in context with other standing stones or other features pointing to their purpose (Avner 1990, 133; Gophna and Ayalon 2004, table 1).

11 I would like to thank Dr Uzi Avner for giving me access to his unpublished PhD. (Avner 2002). Avner’s 2002 analysis of standing stone sites in the Negev and the Sinai was based on 207 monuments. The number of identified monuments has since risen to approx. 400 standing stone sites (not including the hundreds of other cult sites containing standing stones) (Avner 2002; Avner pers. comm. 2012).

12 Hugo Gajus Scheltema has voiced his concern on the issue of the preservation of these sites (Scheltema 200, 115–117). This concern is very relevant. As late as the spring of 2012 the stone line at Lejjun was damaged, apparently by looters, who have dug 2 m. into the ground at the base of some of the standing stones tumbling over two and damaging a third (pers. comm. Jennifer E. Jones 2012). In addition large-scale quarrying is threatening to damage the ceremonial site Murayghat (Savage 2010).

13 It is interesting to note that early accounts of standing stones in the vicinity of Bab edh-Dhra’ have been reported (Albright 1924, 6, 10; 1926, 58–59). Unfortunately these have since disappeared (Philip 2008, 173).

14 I would like to thank Carsten Körber for the opportunity to study the ceramic material from Dhra’. I would also like to thank the staff at the German Protestant Institute of Amman (GPIA) and especially Dr Jutta Häser, for making my study and thus this publication possible. Furthermore I would like to extend my thanks to Dr Susanne Kerner for initiating my study of this material.

15 This is a feature found at monuments towards south, in the Negev and the Sinai regions (Avner 2002, 66, 84), but has also been identified farther north at Mutawwaq (Fernández-Tresguerres Velasco 2011, 116, 118, fig. 7).

16 However, it should be noted that excavations uncovered only small samples of the site (area IV and V), beyond the areas concentrating on the standing stone monument (area II) and the wall (area I and III).

17 Area VI had an equally high proportion of ceramics, but since only surface collection of ceramics were conducted in this area, this feature was interpreted as signifying erosion from other parts of the site or as suggesting underlying archaeological strata (Andersson 2011, 80).

18 With the finds of pestles, a grinder and flints at Dhra’ it is interesting to note the character of finds from the Negev and Sinai sites, which according to Avner, often included flint and grinding tools (Avner 2002, 76–78).

19 The investigations of Khirbat Iskander monuments will be published in the future (D’Angelo 2010, 209–210; Richard 2010, 10).

Bibliography

Abu Shmais, A. and Scheltema, H. G. (2011) A Menhir discovered at Wadi es-Saqra, Amman district, Jordan. In Tara Steimer-Herbet (ed.) Pierres levées, steles anthropomorphes et dolmens. Standing stones, anthropomorphic Stelae and Dolmens, 41–46. British Archaeological Report S2317. Oxford, Archaeopress.

Al Ajlouny, F., Douglas, K., and Khrisat, B. (2011) Spatial Distribution of the Early Bronze Clay Figurative Pieces from Khirbet ez-Zeraqõn and its Religious Aspects. Ancient Near Eastern Studies 48, 88–125.

Albright, W. F. (1924) The Archaeological Results of an Expedition to Moab and the Dead Sea. Bulletin of the American schools of Oriental Research 14, 2–12.

Albright, W. F. (1 926) The Jordan Valley in the Bronze Age. Annual of the American School of Oriental Research 6, 13–74.

Andersson, A. (2011) An Analysis of the Ceramic Assemblage from the EBA Period Site, Dhra’, in the southern Levant, Jordan. Unpublished MA thesis. University of Copenhagen.

Avner, U. (1990) Current Archaeological Research in Israel: Ancient Agricultural Settlement and Religion in the Uvda Valley in Southern Israel. Biblical Archaeologist, 53/3, 125–141.

Avner, U. (2002) Studies in the Material and Spiritual Culture of the Negev and Sinai Populations, during the 6th–3rd Millennia B.C. Unpublished PhD thesis. Hebrew University.

Ben-Ami, D. (2008) Monolithic Pillars in Canaan: Reconsidering the Date of the High Place at Gezer. Levant 40/1, 17–28.

Ben-Tor, A. (1977) Cult Scenes on Early Bronze Age Cylinder Seal Impressions from Palestine. Levant 9, 90–100.

Ben-Tor, A. (1992) New Light on Cylinder Seal Impressions Showing Cult Scenes from Early Bronze Age Palestine. Israel Exploration Journal 42/3–4, 153–164.

Chesson, M. (2003) Households, Houses, Neighbourhoods and Corporate Villages: Modelling the Early Bronze Age as a House Society. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 16/1, 79–102.

Chesson, M. and Philip, G. (2003) Tales of the City? Urbanism in the Early Bronze Age Levant from Mediterranean and Levantine Perspectives. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology, 16/1, 3–16.

Chesson, M., Makarewicz, C., Kuijt, I. and Whiting, C. (2005) Results of the 2001 Kerak Plateau Early Bronze Age Survey. In N. Serwint (ed.) Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 59, 1–63. Boston, Massachusetts, American Schools of Oriental Research.

Crumley, C. (1995) Heterarchy and the Analysis of Complex Societies. Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 7/1, 1–5.

D’Angelo, J. (2010) Excavations of the Area E Cemetery. In S. Richard, J. C. Long, P. S. Holdorf and G. Peterman (eds) Khirbat Iskander, Final Report on the Early Bronze IV Area C “Gateway” And Cemeteries, 209–222. Archaeological Report 14. Boston, American Schools of Oriental Research.

Fernández-Tresguerres Velasco, J. A. (2011) Pierres dressées dans la région de Mutawwaq (Jordanie). In T. Steimer-Herbet (ed.) Pierres levées, steles anthropomorphes et dolmens. Standing stones, anthropomorphic Stelae and Dolmens, 113–122. British Archaeological Report S2317, Oxford, Archaeopress.

Genz, H. (2010) Thoughts on the Function of ‘Public Buildings’ in the Early Bronze Age Southern Levant. In D. Bolger and L. C. Maguire (eds) The Development of Pre-State Communities in the Ancient Near East. Studies in Honour of Edgar Peltenburg. 46–52. Themes from the Ancient Near East BANEA Publication Series, 2. Oxford, Oxbow Books.

Glueck, N. (1939) Explorations in Eastern Palestine III. Annual of the American Schools of Oriental research 18/19. Chicago, American Schools of Oriental Research.

Gophna, R. and Ayalon, E. (2004) Tel Ashir: An Open Cult Site of the Intermediate Bronze Age on the Bank of the Poleg Stream. Israel Exploration Journal 54/2, 145–173.

Greenberg, R. and Eisenberg, E. (2002) Egypt, Bet Yerah and Early Canaanite Urbanization. In E. C. M. Van den Brink and T. E. Levy (eds) Egypt and the Levant. Interrelations from the 4th through the Early 3rd Millennium B.C.E., 213–222. London, Leicester University Press.

Insoll, T. (2004) Archaeology, Ritual, Religion. London, Routledge.

Jones, J. E. (2006) Reconstructing Manufacturing Landscapes at Early Bronze Age Al-Lajjun, Jordan. The First Season (2003). Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 50, 315–323.

Jones, J. E. (2007a) A Landscape Approach to Craft and Agricultural Production. In T. E. Levy, P.M. Daviau, Y. Michéle, W. Randall and M. Shaer (eds) Crossing Jordan. North American Contributions to the Archaeology of Jordan, 277–284. London, Equinox Publishing.

Jones, J. E. (2007b) Craft Production and Landscape in the Early Bronze Age Settlement at Al-Lajjun, Jordan. In F. Kraysheh (ed.) Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan IX: Cultural Interaction through the Ages, 123–131 place of publication and publisher?

Kerner, S. (2008) The Transition Between the Late Chalcolithic and the Early Bronze Age in the Southern Levant. In H. Kühne, R. M. Czichon, Rainer and F. J. Kreppner (eds) Proceedings of the 4th International Congress of the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. 29 March–3 April 2004. Freie Universität Berlin. Vol. 2: Social and Cultural Transformation. The Archaeology of Transitional Periods and Dark Ages Excavation Reports, 155–166. Weisbaden, Harrasowitz Verlag.

Körber, C. (1993) Edh-Dhra’ Survey 1992. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan. The Kenneth Wayne Russel Memorial Volume XXXVII, 550–553.

Körber, C. (1994a) Archaeology in Jordan: Explorations in adh-Dhra’. In G. L. Peterman (ed.) American Journal of Archaeology (AJA) Vol. 98, no. 3, 533–534.

Körber, C. (1994b) Monolithic pillars in Jordan and the 1992 excavations at Dhra’. In S. Kerner (ed.) The Near East in Antiquity. Archaeological work of the National and International Institutions in Jordan, Vol. IV, 65–74.

Körber, C. (1995) Bereicht über die Grabungskampagne in ed-Dra 1994. Jahrbuch des Deutschen Evangelischen Instituts für Alterwissenschaft des Heiligen Landes, 4, 46–47.

Lapp, N. (2003) Cylinder Seals, Impressions, and Incised Sherds. In W. E. Rast and T. R. Schaub (eds) Bab edh-Dhra’: Excavations at the Town Site (1975–1981) Part 1: Text. Reports of the Expedition to the Dead Sea Plain, Jordan, Vol. 2, 522–565. Winona Lake, Indiana, Eisenbrauns.

MacDonald, B., Herr, L. G., Neeley, M. P., Gagos, T., Moumani, K. and Rockman, M. (2004) The Tafilah-Busayrah Archaeological Survey 1999–2001, West-Central Jordan, Archaeological Report 9. Boston, American Schools of Oriental research.

Mazar, A. and Miroschedji, P. (1996) Hartuv. An Aspect of the Early Bronze Age I Culture of the Southern Israel. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 302, 1–40.

Milevski, I. (2011) Early Bronze Age Goods Exchange in the Southern Levant. A Marxist Perspective. London, Equinox Publishing.

Miller, J. M. (1991) The Survey. In J. M. Miller (ed.) Archaeological Survey of the Kerak Plateau. American Schools of the Oriental Research, 1–22. Archaeological Report 1. Atlanta, Scholars Press.

Miller, J. M. et al. (1991) The Sites. In J. M. Miller (ed.) Archaeological Survey of the Kerak Plateau. American Schools of the Oriental Research, 23–168. Archaeological Report 1. Atlanta, Scholars Press.

Mortensen, P. and Thuesen, I. (1998) The Prehistoric Periods. In M. Piccorillo and E. Alliata (eds) Mount Nebo. New Archaeological Excavations 1967–1997, 85–99. Jerusalem, Studium Biblicum Franciscanum.

Nigro, L., Sala, M. and Polcara, A. (2008) Preliminary Report of the Third Season of Excavation of Rome “La Sapienza” University at Khirbat al-Batrawi (Upper wadi Az-Zarqa’). Annual of the Department of Antiquities in Jordan 52, 209–230.

Palumbo, G. (1998) The Bronze Age. In M. Piccorillo and E. Alliata (eds) Mount Nebo. New Archaeological Excavations 1967–1997, 100–109. Jerusalem, Studium Biblicum Franciscanum.

Palumbo, G. (2008) The Early Bronze Age IV. In R. B. Adams (ed.) Jordan. An Archaeological Reader, 227–262. London, Equinox Publishing.

Philip, G. (2003) The Early Bronze Age of the Southern Levant: A Landscape Approach. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology, 16/1, 103–132.

Philip, G. (2008) The Early Bronze Age I–III. In R. B. Adams (ed.) Jordan. An Archaeological Reader, 161–22 6. London, Equinox Publishing.

Renfrew, C. (1994) The Archaeology of Religion. In C. Renfrew and E. B. W. Zubrow (ed.) The Ancient Mind. Elements of Cognitive Archaeology, 47–54. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Richard, S. (2010) Introduction. In S. Richard, J. C. Long, P. S. Holdorf and G. Peterman (eds) Khirbat Iskander, Final Report on the Early Bronze IV Area C “Gateway” And Cemeteries, 1–19. Archaeological Report 14. Boston, American Schools of Oriental Research.

Richard, S. and Boraas, R. S. (1984) Preliminary Report of the 1981–1982 Seasons of the Expedition to Khirbet Iskander and its Vicinity. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 254, 63–74.

Richard, S. and Long Jr, J. C. (2006) Three Seasons of Excavation at Khirbet Iskander, 1997, 2000, 2004. Annual of Department of Antiquities of Jordan 49, 261–276.

Richard, S. and Long Jr, J. C. (2007) A City in Collapse at the End of the Early Bronze Age. In T. E. Levy, P. M. Daviau, Y. Michéle, W. Randall and M. Shaer (eds) Crossing Jordan. North American Contributions to the Archaeology of Jordan, 269–279. London, Equinox Publishing Ltd.

Sala, M. (2011) Sanctuaries, Temples and Cult places in Early Bronze I Southern Levant. Vicino & Medio Oriente, XV, 1–32.

Savage, S. H. (2010) Jordan’s Stonehenge: the Endangered Chalcolithic/Early Bronze Age Site in al’Murayghat – Hajr al-Mansûb. Near Eastern Archaeology 73/1, 32–46.

Savage, S. H. (2012) From Maadi to the plain of Antioch: What can Basalt Spindle Whorls Tell Us about Overland Trade in the Early Bronze I Levant? In M. S. Chesson, W. Alfrecht and I. Kuijt (eds) Daily Life, materiality and Complexity in Early Urban Communities of the Southern Levant. Papers in Honor of Walter E. Rast and R. Thomas Schaub, 119–138. Winona Lake, Eisenbrauns.

Savage, S. H. and Rollefson, G. O. (2001) The Moab Archaeological Resource Survey: Some Results from the 2000 Field Season. Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 45, 217–236.

Scheltema, H. G. (2008) Megalithic Jordan. An Introduction and Field Guide. American Center of Oriental Research Occasional Publication 6. Amman, American Center of Oriental Research.

Scheltema, H. G. (2011) Standing Stones in Jordan: Some Remarks on Occurrence, Typology and Dating. In T. Steimer-Herbet (ed.) Pierres levées, steles anthropomorphes et dolmens. Standing stones, anthropomorphic Stelae and Dolmens, 47–52. British Archaeological Report S2317. Oxford, Archaeopress.

Schick, C. (1879) Journey into Moab. Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement 11/4, 187–192.

Steadman, S. R. (2009) The Archaeology of Religion: Cultures and Their Beliefs in Worldwide Context. Walnut Creek, Left Coast Press.

Yekutieli, Y. (2001) The Early Bronze Age IA of the Southern Canaan. In S. R. Wolff (ed.) Studies in the Archaeology of Israel and Neighbouring Lands in Memory of Douglas L. Esse. Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 59, 659–688. Chicago, Illinois.