A sanctuary, or so fair a house? In defense of an archaeology of cult at Pre-Pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe

The tell of Göbekli Tepe1 is situated about 15 km northeast of the modern town of Şanlıurfa between the middle and upper reaches of the Euphrates and Tigris and the foothills of the Taurus Mountains (Fig. 7.1). Rising to about 15 m on a limestone plateau at the highest point of the Germuş mountain range, the mound is spreading on an area of about 9 ha, measuring 300 m in diameter. The location was known as a Pre-Pottery Neolithic site since a combined survey by the Universities of Chicago and Istanbul in the 1960s (Benedict 1980), but the architecture the mound was hiding remained unrecognised until its discovery in 1994 by Klaus Schmidt (Schmidt 2006; 2012). Since then annual excavation work was conducted, uncovering monumental buildings not suspected in such an early context (Schmidt 2001; 2006; 2010).

At current state of research it is possible to distinguish at least three stratigraphic layers. Their archaeological dating based on typological observations is backed up and confirmed by a growing number of radiocarbon dates (Dietrich 2011; Dietrich and Schmidt 2010). The hitherto oldest layer uncovered at Göbekli Tepe, Layer III, belongs to the 10th millennium BC, the earlier phase of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN A). At Göbekli Tepe this layer produced monumental architecture characterised by 10–30 m wide circles formed by huge monolithic pillars of a distinct T-like shape (Fig. 7.2). These pillars, reaching a height of up to 4 m, are interconnected by walls and benches. They are always orientated towards a central pair of even larger pillars of the same shape. Hands and elements of clothing betray the anthropomorphic character of the pillars (Fig. 7.3), the T-head being an abstract depiction of the human head viewed from the side, while the shaft forms the body. Five stone circles, Enclosures A, B, C, D and G were discovered in the main excavation area (Fig. 7.4) at Göbekli Tepe’s southern depression. Enclosure F was excavated at the southwestern hilltop and Enclosure E is situated at the western plateau. While Enclosures A, B, F and G are still under excavation, E was recognised as a completely cleared enclosure of which only the floor and two pedestals cut out of the bedrock for the central pillars are still visible.

A younger layer is superimposing this monumental architecture in some parts of the mound. This Layer II2 is dating to the 9th millennium BC and can be set into the early and middle PPN B. The smaller, rectangular buildings, measuring about 3 × 4 m, characteristic for this stratum may be understood as a reduction of the noticeably larger older enclosures. Number and height of the T-shaped pillars are reduced, often only two small central pillars are present, the largest among them not exceeding a height of 2 m. Sometimes these rooms even show no pillars at all, a certain degree of expenditure is visible in the floors, which consist of terrazzo-like pavements. Thereafter, building activity at Göbekli Tepe seems to have come to an end. Layer I describes the surface layer resulting from erosion processes as well as a plough horizon formed in the more recent centuries.

The question: special building, sanctuary, temple or “so fair a house”?

From its discovery on, the interpretation of Göbekli’s suprising architecture has centered around the terms ‘special buildings’ (Sondergebäude), ‘sanctuaries’, or ‘temples’. This line of interpretation has recently been called into question by E. B. Banning. He challenges the existence of pure domestic or ritual structures for the Neolithic (Banning 2011, 27–629), arguing that archaeologists tend to impose western ethnocentric distinctions of sacred and profane on prehistory, while anthropology in most cases shows these two spheres to be inseparably interwoven (Banning 2011, 624–627, 637). In his eyes, buildings always combine both aspects with a more expressive or discrete presence of symbolic content, and Göbekli Tepe was a settlement with buildings rich in symbolism, but nevertheless domestic in nature.

In this short paper we want to take his approach to the site as a starting point to discuss the possibility of an archaeology of cult or even religion at Göbekli Tepe. First the interpretational framework will have to be clarified, before in a second step a detailed discussion of relevant archaeological data from Göbekli and other sites of the Near Eastern Early Neolithic follows.

Fig. 7.1: Aerial view of Göbekli Tepe before excavation work started (photo: O. Durgut, © DAI).

Approaching the sacred

That cult, ritual and ultimately religion are concepts often cited but seldom well defined by archaeologists or securely attested for in the archaeological record is already a commonplace repeated in many writings on sites and finds (cf. Bertemes and Biehl 2001, 14–15 for an account of references). Another such commonplace is the insight that archaeologists tend to classify findings especially hard to interpret as ‘cultic’. Mix that with the now widespread post-modernist proposition that archaeologists can only understand and classify what they already know, that every single interpretation is biased by the scientist’s individual and cultural background, and we have written a short but devastating obituary for an archaeology of cult and religion. Thoughts in this direction are anything but new. Already in 1954 C. Hawkes placed ‘religious institutions and spiritual life’ on the last – and by purely archaeological evidence without the aid of texts hardest to reach – step on what today often is referred to as his ‘ladder of inference’ (Hawkes 1954, esp. 161–162). But does this mean that we have to confine ourselves to just file special sites and finds as something out of the norm, unusual and surprising without further investigating into their significance? A growing number of comprehensive studies (e.g. Renfrew 1994; Biehl et al. 2001; Insoll 2004; Kyriakides 2007; Insoll 2011) and in-detail approaches to the Near Eastern early Neolithic (e.g. Cauvin 1994; Özdoğan and Özdoğan 1998; Schmidt 1998; Gebel et al. 2002; Verhoeven 2002; Hodder 2010) speaks out in favor of the possibility of archaeological insights into beliefs even for non-literate times and societies, however restricted by the limits of archaeological evidence.

It is obviously a futile task to overcome the historically and biographically bound individual in the interpretation of the archaeological record. It is the nature of the human mind to explain the world in relation to former experiences, indifferent whether they form part of the individual’s own biography or have been adopted from others. This will come even more into play when we face an assemblage lacking so many parts of the puzzle as archaeological sites usually do. An archaeology without intuitive reasoning and clues drawn intentionally or subconsciously from analogies is hardly imaginable. And it is absolutely clear that every approach to a site can lead only to one, not the narrative of the respective place and time. But nevertheless there are of course interpretations more probable than others, more appropriate to the evidence left behind. We have to try and get in touch as much as possible with the ‘ancient mind’ to assess the probability of one interpretation over another.

Fig. 7.2: Göbekli Tepe: aerial view of the main excavation area, Enclosure D in the foreground (photo: N. Becker, © DAI).

Banning tries to achieve this by collecting ethnographic evidence showing that for many societies there are no hard boundaries between the sacred and the profane (Banning 2011, 624–627). It is certainly true that we perceive this boundary much stricter after centuries of secularisation in the western hemisphere (Banning 2011, 637) and therefore tend to form an equation between unusual/uncommon=sacred/ritual, although this differentiation also exists in some non-western societies, as Banning (2011, 624) admits. He then moves on to show how this entanglement between sacred and profane may lead to a reality, in which ‘seemingly mundane things, such as houses, could be sacred and that some sacred things, such as amulets, could be far from awe inspiring’ (Banning 2011, 624). He then lists aspects of Neolithic Near Eastern domestic architecture, like in-house inhumations, caches and wall paintings as proof for the sacred leaking into everyday live (Banning 2011, 627–629), making a clear distinction impossible.

Fig. 7.3: Arms, hands and elements of clothing reveal the anthropomorphic character of Göbekli Tepe’s pillars (Pillar 31 in the centre of Enclosure D) (photo: N. Becker, © DAI).

These arguments are valid and add to a very possible narrative of this aspect of Neolithic life. In fact the idea of manifestations of the sacred in houses or parts of houses is neither new, nor surprising. One of the main protagonists of this line of thought is M. Eliade, who, based on vast ethnographic and historical evidence, argued vehemently for the entanglement of sacred and profane as the primordial state in human societies (Eliade 1959). Eliade starts from the observation that building a house, i.e. settling down in an area, was a crucial and potentially dangerous act in traditional societies: ‘for what is involved is undertaking the creation of the world that one has chosen to inhabit’ (Eliade 1959, 51). The newly erected dwelling had to fit into the world created by supernatural powers, and this was achieved by repeating the cosmogenic acts of deities through a construction ritual, or by projecting the order of the cosmos into the construction, e.g. by erecting a central column which equals the axis mundi, the center of the world (Eliade 1959, 52–53). Houses in this way always incorporated a sacred aspect, or even reflected the image of a world ordered by religious principles. In Eliade’s (1959, 43–44) view, the house as a representation of the cosmos reassured man of living in an ordered world: ‘where the break in plane was symbolically assured and hence communication with the other world, the transcendental world, was ritually possible’.

Fig. 7.4: Plan of excavations and geophysical surveys at Göbekli Tepe (graphics: T. Götzelt, © DAI).

But none of these musings speaks against special loci, where belief and cult, which are present in every aspect of life, focus. In Eliade’s words, besides the sacred aspects of houses: ‘the sanctuary – the center par excellence was there, close to him [man], in the city, and he could be sure of communicating with the world of the gods by entering the temple’ (Eliade 1959, 43).

These more theoretic thoughts are underlined by ethnographic evidence, which shows societies making no strict differentiation between holy and profane in everyday life nevertheless to have spatial focal points of the holy and cult, which do not have to be associated with domestic architecture. New Guinea seems to come handy for ethnographic analogies regarding the Neolithic on many levels, as cultural features like the extensive use of stone axes (Pétrequin – Pétrequin 2000), lithics in general (Silitoe and Hardy 2003) and cult practises3 including plastered skulls of ancestors and slain enemies (Kelm 2011) seem to relate easily to phenomena known archaeologically from that period4.

As far as details on the multitude of traditional religions of New Guinea are known, they all were present in every aspect of life (Stöhr 1987, 424–425). Nevertheless, for example Zöllner (1977, 332–336) has noted in his extensive study of the Jalî in Iriyan Jaya that a distinct religious realm exists, specified by the term ûsa. Phenomena can thus be classified as being sacred or not; the marked difference to western thought is the general interrelation – be it weaker or stronger – of religion with every other aspect of life. This notion of the sacred is to be found all over New Guinea (Stöhr 1987, 426). Having said this, and agreeing that the sacred is clearly present in the domestic realm, there are still different types of special buildings, in which sacred activity concentrates. Many rites and festive repetitions of myths center in the men’s houses (Stanek 1987; Konrad and Biakai 1987), which exist in nearly every village. These are multifunctional buildings, which combine domestic aspects (sleeping room for the men segregated from the women) with ancestor veneration (storing of skulls, of ritual paraphernalia, carved posts representing ancestors), cult activity (storage room for masks worn in ritual acts, exclusive parts of rituals or preparations for rituals performed only there), and political action (assembly of the men as highest decision making body, jurisdiction). These buildings are clearly not reducible to a function as sanctuaries, and often they are not constructed very differently from the other houses of a village, but recognisable due to their central placing in the village plan, often combined with dancing or assemblage places (Cranstone 1971, 134; Stanek 1987, 624–626; there may be differences in the inner spatial division: Roscoe and Telban 2004, 109). But then there are also examples of special cult-houses.

The Tifalmin of highland New Guinea (settling in the valley of the Ilam, a tributary of the Sepik) constructed intra-village men’s houses to guard males from the negative influences women are thought to have on their social qualities necessary to become influential big men (Cranstone 1971, 134). These houses share the same construction with the family houses. But central to cult activity in their ancestor cult is a separate cult-house in one village (Brolemavip) that differs from the usual construction ‘in having its façade covered with about twenty carved boards set vertically’ (Cranstone 1971, 137). This house may only be entered by senior men and contains ancestral relics (e.g. bones, wisps of beard), a crocodile skull and two clubs with stone heads, while the walls are lined with the lower jaws of pigs (Cranstone 1971, 137). Further west, in the Star mountains region, for the Mountain Ok, a wide range of such cult-houses (bokam iwo) has been recorded, standing usually in an exposed position in the villages (in the middle of a big feasting place) but differing markedly in size among one another and from domestic architecture (sometimes they are even smaller), but usually bearing some architectural differences to the latter (Michel 1988, 229). They contain a large collection of pig and marsupial jaws, feathers, bows, arrows, plants, ancestor relics and other objects, arranged to elaborate patterns rather freely around certain basic rules regarding house sides and levels (Michel 1988, 230). We do not want to enter into the details of these conceptions here, but only to reinforce the point that specialised cult architecture does exist in societies not perceiving the antagonism of holy and profane like western people do. And, to complete the argument, cult areas and buildings in New Guinea also occur completely detached from the domestic sphere of the village.

As an example, we want to insist shortly on the case of the Tolai on the Gazelle Peninsula in northeastern New Britain. The bigger part of (male) Tolai society was engaged in two secret societies, the dukduk and the iniet. While the first has raised the interest of early ethnographers due to the splendid masks worn during ritual and exists in spite of colonial attempts of suppression in modified form till today (Mückler 2009, 165–167), the second one was rather quickly and efficiently suppressed by German colonial officers due to rumors about sexual and cannibalistic excesses during ritual meetings held in remote places (Kroll 1937, 201–202), which renders a detailed description partly problematic (Koch 1982, 14–16; Epstein 1999, 274). Nevertheless a fairly coherent picture of a male secret society with aspects of ancestor veneration and sorcery emerges, which is of interest to the questions discussed here.

As Kroll states, the majority of men in the northeastern Gazelle Peninsula formed part of the iniet; the main advantage of being an initiate was the knowledge of sorcery passed on to the tena iniet and social status ranging from admiration to fear vis-à-vis a powerful sorcerer (Koch 1982, 16; Epstein 1999, 274–276). The centre of iniet belief seems to have been the possibility of a ‘spirit or soul entering into and thus taking on the form of a bird […], a pig, a shark, or a snake, or even another person’ (Epstein 1999, 275) and profiting from these abilities. The knowledge of these transformations was handed down to initiates at remote places in the woods called marawot, were also the other rituals took place (Kroll 1937, 182). The marawot is described as a rectangular space of 10 × 30 m, surrounded by mats as visual protection; in the middle was a dancing place again screened by mats, in front of which a small hut stood (Koch 1982, 19). Not only ceremonies were held here, but also the paraphernalia were stowed in the hut or buried nearby when no ceremonies were held (Koch 1982, 19, 24). It was forbidden for non-initiates (and women) to enter the precinct; should a man accidently find the place he was menaced with death and could, as a last resort, beg to be accepted in the iniet (Kroll 1937, 182). Admission included the payment of a sum of shell money and a complex multi-phased ceremony (Kelm 2011, 175). A key moment in this ceremony was the presentation and explication of the stone sculptures of the iniet spirits to the initiate, who also got a figure of his own as well as a new name (Koch 1982, 19–20).

The elaborate stone sculptures, which often were painted and adorned with organic materials (e.g. to imitate beards) have early caught the attention of the Europeans (Koch 1982). They show men and women as well as a wide range of animals and are embedded in a complex kinship system, bearing names and being related to other sculptures (Kroll 1937, 197–200; Mückler 2009, 168). The sculptures are thought to be the domicile of – or actually the – powerful ancestors (former members of the iniet) and contact with them is dangerous even for initiates. Much more could be said about this interesting case study, but this short account should suffice to show that even if we have to act on the assumption of entangled spheres of holy and profane this does not exclude special places or buildings destined for cultic activities.

We do not want to fall into the easy trap of taking superficial compliances with Göbekli like the striking stone sculptures as an argument for determinations of the latter’s character and function. The discussion should neither center on direct analogies, nor on the general possibility of cult architecture in prehistory, but on identifying it archaeologically.

A research agenda for an archaeology of cult?

The past three decades have seen several attempts to overcome Hawkes’ concerns at least partly and to develop methodologies to pin down the elusive in the archaeological record. The approaches to the topic are as diverse as the theoretical spectrum of archaeology. Detailed accounts of these attempts fill many pages of books on the topic (e.g. Insoll 2004, 42–103); it is neither possible nor necessary to repeat the pros and contras of different approaches here. What is needed instead is a tool, which helps us to separate buildings more domestic in nature from those related primarily to cult. C. Renfrew’s archaeological indicators of ritual, first defined in his seminal work on Phylakopi (Renfrew 1985, 18–21) and refined later on (Renfrew 1994; 2007) spring to mind here. In the 1994 version of the list, he groups 16 hints for recognising cult in four categories (for the following Renfrew 1994, 51–52).

His first point is “focusing of attention”. This is achieved (1) through ritual taking place in a location marked by special natural features such as mountain tops, caves etc., or (2) in a special building. Further, (3) “attention focusing devices” may be used, “reflected in the architecture, special fixtures (e.g. altars, benches, hearths) and in moveable equipment”, and (4) the sacred area may be rich in repeated symbols. The second category of indicators regards a function as a “boundary zone between this world and the next” (or, in Renfrew 2007, 115 “special aspects of the liminal zone”) and includes (5) “conspicuous public display (and expenditure)” during ritual as well as “hidden exclusive mysteries” visible in the architecture and (6) concepts of cleanliness and pollution as well as maintenance regarding the sacred zone. The third category, “presence of the deity” may include (7) cult images or representations, and (8) an iconography that may relate to the deities or their myths, often including animal iconography relating to certain supernatural powers. This ritualistic symbolism may (9) relate to symbols used in funerary ritual or rites de passage. The last category, “participation and offering” incorporates (10) special gestures of adoration, which may reflect in imagery, (11) “devices for inducting religious experiences (e.g. dance, music, drugs and the infliction of pain)”, (12) sacrifice of animals or humans, (13) consumption or offering of food and drink, (14) sacrifice of objects, maybe including breaking, hiding, discard, (15) a great investment in wealth reflected in equipment and offerings, and (16) also in the sacred structures.

It has to be clear from the start that these categories elaborated for a Greek sanctuary may, at least partly, not be applicable everywhere. If architecture is missing, some of the hints will not be usable, and a complex and repeated action is necessary to leave traces in the archaeological record. Some points may be modified slightly, or combined, as for example cult architecture may be erected in special natural places, and ‘deity’ may not be the term to use in belief systems that e.g. center around ancestors, like Renfrew (2007, 115) acknowledges by re-naming the category to “presence of the transcendent and its symbolic focus”. Critique has aimed especially at the seemingly stereotype checklist-character (e.g. Insoll 2004, 99–100), and we agree that just ticking off indicators will not suffice to identify religion and cult. But Renfrew’s list does not imply this necessarily, and was not intended to be used in that way by its author (Renfrew 1994, 51–52). The archaeologist has to fill the points with life and to add further evidence where necessary. Renfrew (2007, esp. 115) himself has addressed critique to his approach by stating that the indicators will identify ritual, regardless whether it is secularly or religiously motivated. He concludes that categories 2 and 3 may relate more securely to transcendental aspects, and stresses especially the role of high effort and labor input in monumental sites as an indicator for “some more holistic belief system, in which religious belief must have been at least one component of the motivation” (Renfrew 2007, 115, 120–121).

As justified as some of the critique may be, obviously a strictly archaeological framework is needed for identifying cult, as some recent studies seem to be more occupied with the identification of religion in ethnographic examples or in historical times than with the actual archaeological record. There is an especially big gap between living culture and archaeology when non-material aspects are concerned, one which cannot be simply filled in by colourful anthropological evidence. As archaeologists we have to base our assumptions on the archaeological record, and sadly Renfrew may be right in stating that cult and religion are only discernible “where religious practices involve either the use of special artifacts or special places, or both” (Renfrew 1994, 51). There are certain limits to archaeological inference, and we agree that it will be a much more possible task to discern sacral ritual, e.g. repeated acts that have left significant material evidence, than the complex system we address with the term ‘religion’ (Renfrew 1994, 51). To assure that Renfrew’s indicators are a viable tool, the small excursus to New Guinea may not only demonstrate the possibility of specialised cult architecture in traditional societies, it can be used also as a test ground. Would the indicators lead an archaeologist to interpret Melanesian cult-houses and iniet gathering places as part of the transcendental belief system? In answering this question we will have a look especially at the categories identified by Renfrew as relating more securely to cult.

(1–2) Cult-houses lie in exposed spatial settings inside the village, often surrounded by dancing grounds, while iniet cult places lie outside settled areas in the woods. Cult-houses differ in construction from domestic buildings; iniet sites have special constructions for ritual activities and storing the paraphernalia. (3) Cult houses have relicts arranged in specific, visually impressive patterns, in the iniet elaborately worked and decorated stone sculptures are of central importance. (4) The cult house inventory consists of symbolic objects of different classes; the iniet sculptures represent a system with fixed, repeated symbols. (5) Both cult houses and iniet places have restrictions regarding the persons allowed to enter (mysteries revealed only to initiates), knowledge is kept secret. This reflects in the architecture (sight protection at the marawot, screened, unaccesable cult-houses). Conspicuous display of symbolism exists for those taking part in the cult. (6) Iniet places are arranged and maintained by participators in the cult; cult-houses are cared for by one specially elected person (Michel 1988, 229–230). Concepts of pollution are expressed for example in eating taboos for iniet members (Kroll 1937, 201; Koch 1982, 19), however this is not visible archaeologically. (7) Cult images are evident for the iniet, however it is hardly imaginable that their meaning would be understood without an oral tradition; representations in the form of ancestor-related artefacts and animal skulls are found in the cult-houses. (8) An iconography relating to ancestors and myths is clear for the iniet. In the cult-houses it does exist in the arrangement of objects and the objects themselves, but would hardly be reconstructible when one imagines an archaeological context mixed-up due to depositional and post-depositional processes. (9) Regarding the relations to other cultic activities, iniet sculpture is not used outside the iniet, while symbolism related to ancestors will be used generally in ceremonies; it remains unclear whether this connection would be attestable archaeologically. (10) Special gestures of adoration seem not to be reflected in iconography. (11) Dance and music play an important role in ceremonies, for the iniet they would be provable through miniature depictions of musical instruments (Kroll 1937, 191, fig. 21). (12) Sacrifice of animals or humans is not attested during the iniet and not at the cult-houses; ironically it is very possible that a house full of animal bones and the plastered skulls present there as well as at the iniet sites would betray the impression of sacrifice to the archaeologist. (13) Consumption of food and drink are important parts of the ceremonies, which possibly would leave traces in the archaeological record. (14) Sacrifice of objects is not evident; however it is possible that iniet sculptures buried at the marawot and items belonging to ancestors in the cult house would be taken by archaeologists as such. (15–16) A great investment in wealth, respectively working time, is evident from the iniet sculptures and the (wooden) décor of the cult-houses.

Summing up, cult-houses and iniet places would be identified without doubt as sacred loci by these criteria, anyway losing a lot of the original meaning, and some items taking on a completely new one (e.g. hidden sculptures transformed to offerings). The minutiae of ancestor veneration or a secret society’s ritualistic acts would not be deducible, but a general notion of cultic/religious behavior would get through.

The next question is, whether Renfrew’s criteria would lead an archaeologist also to regard the men’s houses as sanctuaries. We do not think that this is the case. Men’s houses would fulfill point 1, but are constructed like normal houses. Symbolism would be present in carved posts and items like plastered skulls, but many of the other criteria would be missed. It seems very probable that men’s houses would be categorised as multifunctional buildings due to strong domestic features like bedsteads and resemblances in construction plans with other domestic buildings. As the criteria proposed by Renfrew thus seem to suffice for identifying the transcendent at least on a basic level; the next step will be to apply them to Göbekli Tepe.

(1) Göbekli Tepe lies on the highest point of the Germuş mountain range. The spot is hostile to settlement; today Göbekli is the only place with arable soil on the otherwise barren limestone plateau. Botanical analysis indicates a relatively open, forest-steppe landscape with pistachio and almond trees for the early Neolithic, very sensible to human interference (Neef 2003, 14–15). Degradation of landscape may well have begun during the use-time of Göbekli. Botanical remains show some evidence for hygrophilous vegetation near springs (Neef 2003: 15), but no springs are known in the vicinity of the site and a geological survey revealed artesian phenomena to be excluded in the area (Herrmann-Schmidt 2012, 57). The next accessible springs are located about 5 km linear distance to the northeast (Edene) and to the southeast (Germuş). A group of pits at Göbekli’s western slope could represent rain water cisterns with a total capacity of 15,312 m3 (Herrmann-Schmidt 2012) accumulating enough water for people to stay for longer periods of time, but probably not during the rainless summer. The next Neolithic settlements so far known lie in the plain in immediate vicinity of springs, like Urfa-Yeni Yol (Çelik 2000). Apart from these issues concerning the possibility of permanent settlement in the hostile environment at Göbekli, the impressive and dominant position of the site towering over the Harran plain has to be remarked.

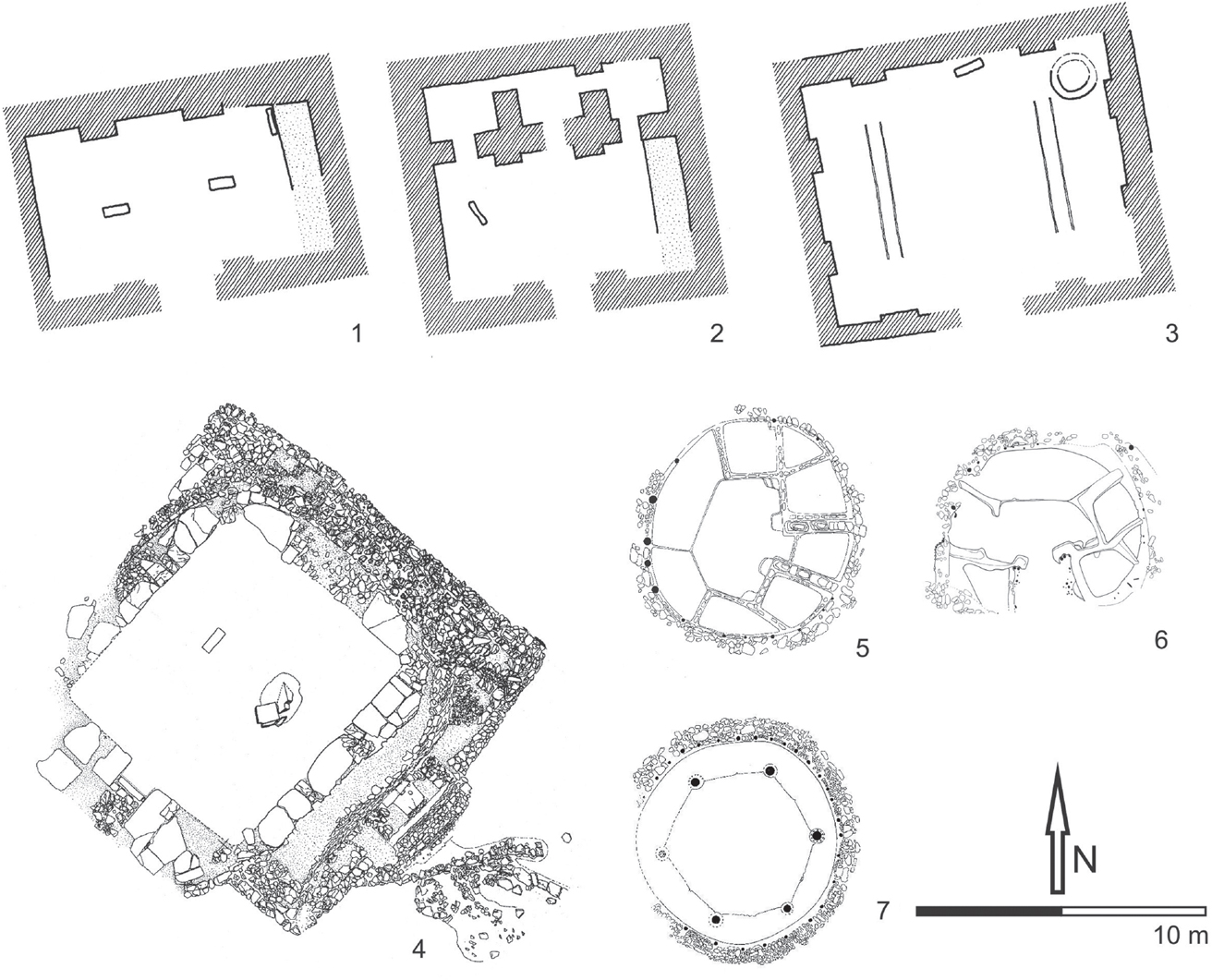

(2) As stated above, Göbekli’s architecture consists exclusively of 20–30 m wide stone circles made up of T-shaped pillars with benches along the perimeter walls in the older Layer III and of smaller, rectangular buildings with smaller and fewer or no pillars at all in Layer II. A geophysical survey has shown that the older round megalithic enclosures existed all over the site (Fig. 7.4). Other building types are not attested at Göbekli. Contemporaneous domestic architecture is well known in the upper Euphrates region due to the long and secure stratigraphy of rectangular freestanding buildings at Çayönü (Schirmer 1988; 1990; Özdoğan 1999) and extensive excavations at Nevalı Çori (Hauptmann 1988). Contemporaneous with Göbekli Tepe in this sequence would be Çayönü’s ‘grillplan-phase’ (PPNA), the ‘channeled’ ground plans (early PPNB; attested for well also in Nevalı Çori), and the ‘cobble paved buildings’ (middle PPNB; cf. Schirmer 1988; 1990: 365–377; Özdoğan 1999, 41). None of these building types is present at Göbekli, and neither are there roasting pits, fireplaces or hearths. What is present on the other hand is a building type which shares commonalities with constructions usually appearing individually in settlement sites and termed ‘special buildings’. Some short examples may suffice to show key resemblances with Göbekli Tepe.

In Çayönü a long sequence of ‘special buildings’ has been documented (Fig. 7.5, 1–3). To the ‘grill plan phase’ belongs the ‘flag stone building’ named after the elaborate construction of its floor with large stone slabs (Schirmer 1990, 378). The walls of the building were subdivided by several projections, in the east probably a bench existed, and standing slabs are interpreted to have held the roof. Somewhat younger is the ‘skull building’, named after the skulls found in ossuaries integrated into its walls and the so-called cellars (Schirmer 1990, 378–382). Benches along the walls seem to have been an important element here, too, standing stone slabs again held the roof. Interior fittings include bull skulls in several phases and a big ‘stone table’. Both buildings are of rectangular or square shape, uncertainties remain due to partly destructions. To Çayönü’s ‘cell plan phase’ belongs the rectangular ‘terrazzo-building’, named after its elaborate red cement-like floor, which is subdivided by four white bands (Schirmer 1990, 382–384). Approximately half of the floor area is disturbed by a later pit, nevertheless some details of inner organisation were recognisable, e.g. a basin of 1.25 m diameter in the northeastern and a table-like stone slab found slightly above the northwestern corner of the building. Characteristic traits of these special buildings are thus the benches hinting at gatherings as one scope, rich and elaborate inner fittings as well as special installations and finds. This pattern repeats itself with finds in other sites.

Placed as well in southeastern Turkey, the settlement of Nevalı Çori has revealed domestic architecture comparable to Çayönü’s ‘channeled phase’ (Hauptmann 1988) as well as a three-phased ‘cult building’ (Hauptmann 1993; 1999, 74–75). Like the other buildings it was erected in limestone masonry with clay mortar, but with an approximately square (Fig. 7.5, 4), not rectangular ground plan, and with benches along the walls. In more or less regular intervals orthostats stood in these benches, of which in most cases only the shaft was preserved. Complete examples from the building’s northern corner show Γ-like heads, a variant of the T-shaped pillars from Göbekli (Hauptmann 1993, 50, 52–53). The latter are also present at Nevalı Çori; of the two central pillars of the building one has a completely preserved T-shape. The building bears not only similarities to Göbekli in its layout (comp. the reconstruction in Becker et al. 2012, fig. 4), a rich inventory of stone sculptures (Hauptmann 1993, figs 19–26) resembles the finds from Göbekli Tepe as well. The aspect of a gathering known already from Çayönü is here clearly expressed in the architecture, with the peripheral pillars surrounding the central pair.

A long list of further examples of ‘special buildings’ in settlements could be reproduced here, as nearly every PPN site excavated on a larger scale features such architecture, but it may suffice to point out the other main type of such buildings, known largely from the region to the southwest of Göbekli. In Jerf el Ahmar (Fig. 7.5, 5) and Mureybet (Fig. 7.5, 6) in northern Syria subterranean round structures have been revealed, whose interior is subdivided in smaller cellular rooms. They are interpreted by the excavators as multifunctional buildings with aspects of storage, gathering and cult (Stordeur et al. 2000, 32–37), the latter inter alia due to the discovery of a headless human skeleton in the central room of one of the buildings from Jerf el Ahmar (Stordeur 2000, 2, fig. 4) and of a cache of two skulls in another one (Stordeur 2000, 1). In the transitional phase between PPNA and PPNB at Jerf el Ahmar another round building with a diameter of 8 m existed (Fig. 7.5, 7), which featured benches with decorated stone plates along the inner walls (Stordeur 2000, 3; Stordeur et al. 2000, 37–41), while the interior was subdivided by c. 30 wooden posts carrying the roof.

Fig. 7.5: ‘Special Buildings’ of the PPN: 1. Çayönü, ‘Flagstone Building’ (after Schirmer 1983, fig. 11c); 2. Çayönü, ‘Skull Building’ (after Schirmer 1983, fig. 11b); 3. Çayönü, ‘Terrazzo Building’ (after Schirmer 1983, fig. 11a); 4. Nevalı Çori (after Hauptmann 1993, fig. 9); 5. Jerf el Ahmar (after Stordeur et al. 2000, fig. 9); 6. Mureybet (after Stordeur et al. 2000, fig. 2); 7. Jerf el Ahmar (after Stordeur et al. 2000, fig. 5).

Summing up, at Göbekli no traces of the well-known PPN domestic architecture exist, but buildings, which at contemporaneous settlement sites form an exception, standing out by rich iconic finds and emphasising the aspect of gathering places through their layouts.

(3) Attention focusing devices are abundant at Göbekli Tepe. The important role of benches has already been stressed, and as in Nevalı Çori the layout of the pillars depicts a gathering. Not only are the richly decorated pillars attention focusing devices par excellence, but as in Nevalı Çori, Göbekli’s buildings have yielded a large series of anthropomorphic and zoomorphic sculptures (Schmidt 2008; 2010), which repeat the same types canonically (e.g. wild boar, snarling predator). Some of these sculptures have cones for being set into the walls, giving the impression of jumping at visitors; others were attached to the pillars, as the impressive high-relief of a predator on Pillar 27 shows. Göbekli has also generated special object classes, which are so far missing at other sites. A striking example are shallow limestone plates with channels, in one case found in situ set inside the terrazzo floor in front of Pillar 9 in Enclosure B. An association with libations seems probable.

But even more striking is that whole object classes known from settlements are missing (Schmidt 2005). Clay figurines are absent completely from Göbekli. This observation gains importance in comparison to Nevalı Çori, where clay figurines are abundant, missing only in the ‘cult-building’ with its stone sculptures and T-shaped pillars (Hauptmann 1993, 67; Morsch 2002, 148). Clay and stone sculptures may thus well form two different functional groups, one connected to domestic space and one to the ‘cult building’ – and to Göbekli Tepe. Awls and points of bone are largely missing from Göbekli. The tasks carried out with them presumingly were not practiced here. Other find groups, like obsidian, are not absent, but clearly underrepresented. From 18 years of excavations at Göbekli Tepe only c. 400 pieces are known, an exceptionally small number compared to the vast amounts of flint present at the site. But this small group is extremely heterogeneous on the other hand. Seven raw materials from four different volcanic regions have been detected.5 Whether this hints at different groups of people congregating at Göbekli remains a point of debate for the moment.

(4) Not only the types of sculptures are canonical, the depictions of animals repeat themselves, too, and are obviously subject to a certain degree of typological standardisation. And the image range of the different enclosures is far from random (Becker et al. 2012, fig. 24). In Enclosure A snakes are the dominating species, in Enclosure B foxes prevail, in Enclosure C boars take over this role, while Enclosure D is more varied, with birds playing an important role. Again the question of different groups present at Göbekli Tepe is posed. At least general assumptions concerning the builders may be drawn. A selection was not only made with objects and depiction types. What is missing completely from Göbekli is female iconography. There is only one woman depicted on a slab in a building from Layer II, but this representation has to be regarded a later graffito due to its style and placement (Schmidt 2006; 2012). Whenever the sex of representations is identifiable, males are portrayed, and ithyphallic depictions are abundant. At Göbekli Tepe only a part of society becomes visible, the male hunter.

To address the next point, from Göbekli’s iconography emerges clearly the site’s role as a “boundary zone between this world and the next”. The imagery is concerned with dangerous animals like scorpions, snakes and predators, sometimes in combination with their apparently dead prey (Notroff et al. 2014). Animals are often shown in unfavourable conditions with their ribs clearly sticking out. Images of that sort are known from other contexts and sites in the Near Eastern Neolithic (Hodder and Meskell 2011) and beyond (Schmidt 2013) reflecting a symbolism of life and death.

Although its complex imagery is difficult to decode, Pillar 43 from Enclosure D bears witness to a certain narrative character of the depictions, which opens up the possibility of myths being portrayed. We want to insist here only on the scenes at the lower right of this pillar, where a headless man is visible, who is accompanied by a large bird; even more birds, namely vultures, can be seen in the pillar’s upper part. Comparable imagery is known from sites like Çatalhöyük (Cutting 2007) and Nevalı Çori (Schmidt 2006, 77–78; 2010, 246–249) and could hint at a concept of death assigning animals a practical role in the excarnation of dead bodies as well as a figurative one in carrying the dead, reduced to their heads, into an afterlife (Schmidt 2006, 78).

Not only the iconography of Göbekli Tepe expresses an atmosphere of death and fear, the material culture seems to corroborate, too, that the enclosures possibly were not exclusively meant for gatherings of the living. Among the rich avifauna of the site (Peters et al. 2005), corvids make up for more than 50%, while in settlement sites they usually do not exceed 5–10% (Peters et al. 2005, 231). The habitat at Göbekli Tepe must have been very attractive for these birds, which are known as necrophagous, a characteristic also applying to a large number of the other animals depicted. In recent campaigns the filling levels of the enclosures have yielded a considerable amount of human bones mixed up with the archaeofauna. Often they show evidence for post-mortem manipulations, mostly cutting marks. At least one aspect of the function of Göbekli Tepe’s enclosures seems to be related to death (Notroff et al. 2014).

(5) Whether at Göbekli “conspicuous public display (and expenditure)” was emphasised or the impression of “hidden exclusive mysteries” was corroborated depends to a certain degree on the reconstruction of the buildings. If we imagine them open to the sky, then a certain public aspect would have to be taken into account, although the group of participants seems to have been restricted, as argued above. Another possibility is a reconstruction along the lines of largely subterranean buildings accessible through openings in the roof, similar to the kivas of the North-American Southwest, rather unimpressive and hidden from the outside. So far no clear indicators for roofs have been found, and the question remains open to debate.

(6) Concepts of cleanliness and pollution and in fact of an ordered and predestined cycle of life are clearly visible for Göbekli Tepe’s enclosures. They were constantly repaired, as for example broken pillars show that were put back in their places. The circles were not left open after abandonment. Enclosures C and D, excavated to ground level recently, were obviously cleared thoroughly of their inventory and backfilled intentionally with homogenous material in a manner which reminds of a burial. During this process sculptures and other items were placed deliberately in the filling (see below, 14). This may also explain the lack of evidence for roofing, as the roofs may have been de-constructed in the process.

(7–8) The presence of ‘deities’ at Göbekli is clearly a highly complex question (Becker et al. 2012). As stated above, Göbekli’s pillars own an anthropomorphic quality. This may best be demonstrated with the central pillars of Enclosure D. At both pillars, reliefs of arms on the broad sides were long known (Fig. 7.3). The eastern Pillar 18 shows in addition a fox in its right arm. At the pillars’ small side there are reliefs in the shape of a crescent, a disc and a motif of two antithetic elements. The western Pillar 31 is wearing a necklace in the shape of a bucranium. The so far hidden lower parts of the pillars’ shafts were unearthed recently. Hands and fingers became visible soon at both pillars, but also an unexpected discovery could be made: both pillars are wearing belts just below the hands, depicted in flat relief. A belt buckle is visible in both cases, and the belts are decorated with symbols. At both belts a loincloth, apparently of fox skins – also depicted in relief – is hanging down. As the loincloth is covering the genital region of the pillars, we cannot be sure about the sex of the two individuals. But since clay figurines from Nevalı Çori, which are wearing belts, always are male, while female depictions lack this attribute (Morsch 2002, 148, 151), it seems highly probable that the pair of pillars in Enclosure D represents males, too.

An anthropomorphic quality of course does not imply that the pillars do necessarily depict human beings. Their highly abstracted character must be considered intentional, since we know of the existence of more naturalistic and life-sized depictions like the contemporaneous ‘Urfa man’ (Bucak: Schmidt 2003; Hauptmann 2003), and numerous heads of such statues were discovered at Göbekli Tepe (Becker et al. 2012, fig. 17). Whether anthropomorphic gods may be presumed for early Neolithic hunter-gatherers is highly questionable (Becker et al. 2012), nevertheless it seems that faceless supernatural beings individualised through symbols are depicted in a canonical way at Göbekli Tepe and other contemporaneous T-pillar sites (see below). Interpretations in the lines of ancestor veneration in societies based on and organised in categories of kinship, maybe in the context of a dualistic organisation reflected in the recurring pair of central pillars, may be a line of thought to be followed (Bodet 2011; Becker et al. 2012), especially as the often discussed ‘Mother Goddess’ is missing at Göbekli and challenged generally as an explanation pattern for Neolithic religion recently (cf. Schmidt 1997, 76–77, fig. 5; Cutting 2007, 128, 132–133; Hodder and Meskell 2011).

(9) The symbol system visible at Göbekli is not restricted to this site and context. The distinctive T-pillars are known from Nevalı Çori and other sites of the Urfa region (e.g. Sefer Tepe, Karahan and Hamzan Tepe: Moetz and Çelik 2012), but the characteristic zoomorphic and abstract signs are known from a wide range of settlement sites in Upper Mesopotamia on shaft straighteners, plaquettes and stone bowls, indicating Göbekli’s catchment area (Dietrich et al. 2012). Apart from special buildings in settlements, these signs seem to play an important role in funerary rites as the graves from Körtik Tepe show, where large numbers of decorated stone bowls have been found (Özkaya and San 2007, fig. 6, 15–18).

(10) To get to Renfrew’s last category, “participation and offering”, the T-shaped pillars are always shown in a fixed position with their hands brought together on the abdomen above the belt, but whether this represents a special gesture of adoration remains unclear.

(11) It is clearly not easy to get a grip on “devices for inducting religious experiences” if they include things like dance, music and the infliction of pain. At least the infliction of fear and the invocation of death seem to have played an important role at Göbekli, as stated above. There is a rich repertoire of PPN dancing scenes (Garfinkel 2003) shedding some light on the nature of early Neolithic feasts. Recent research has also produced tentative evidence for a production and consumption of alcoholic beverages at Göbekli (Dietrich et al. 2012).

(12) Sacrifices of animals or humans are not clearly attested at Göbekli Tepe, one reason is maybe to be seen in the clearance of the enclosures at the end of their lifecycles. Nevertheless there could be evidence for libations (the limestone plates, see above), and structured deposition during refilling activities may have a dedicational character (see below).

(13) Next to the probable consumption of beer, the sediments used to backfill the monumental enclosures at the end of their use-lives give an interesting hint at activities at Göbekli. The filling consists of limestone rubble from the quarries nearby, flint artefacts and animal bones smashed to get to the marrow, clearly the remains of meals. The species represented most are gazelle, aurochs and Asian wild ass, a range of animals typical for hunters. What is not so typical is the sheer amount of bone material, which hints at extensive feasting (Dietrich et al. 2012), whose attendants may have come from considerable distances to Göbekli, if one regards the distribution pattern of the iconography (and maybe the obsidian raw materials).

(14) The filling of the enclosures is also remarkable from another point of view. During refilling, meaningful parts of the enclosures’ fittings were deposited in a very structured manner near to the pillars, most often the central pillars (Becker et al. 2012). This applies to naturalistic human heads broken off from statues like the ‘Urfa man’ as well as to zoomorphic statues, reliefs and other items.

(15–16) Great investment in resources and work is clearly discernible for Göbekli’s enclosures and their fittings. As Renfrew (2007, 120–121) stresses the importance of this point for the detection of cult, and Banning (2011, 632–633) denies high effort for erecting the enclosures, we will go into some detail here. In the case of Enclosure D, the two pillars in the centre are measuring about 5.5 m in height and weigh about 8 metric tons. The labor force necessary to carve the pillars from the rock, for transporting and finally erecting them, was considerable. While, for example, for the giant moai statues of Rapa Nui (Easter Island), with a typical height of 4 m and a weight of 12 tonnes (Kolb 2011, 140) a number of 20 individuals was calculated to be necessary to carve such a statue in their spare time within 1 year (Pavel 1990), and 50–75 people to move it over a distance of 15 km within the course of a week (Van Tilburg and Ralston 2005), ethnographic records from the early 20th century report that on the Indonesian island of Nias 525 men were involved in hauling a megalith of 4 m3 over a distance of 3 km to its final location in 3 days using a wooden sledge (Schröder 1917). That such a large number of participants is not necessarily caused by the labour involved exclusively, shows another example from Indonesia. In Kodi, West Sumba, the transport of the stones themselves used for the construction of megalithic tombs is ritualised and asks for a large number of people involved as witnesses (Hoskins 1986).

However, at Göbekli Tepe the monumental enclosures of Layer III consist of several such megalithic elements cut out of the surrounding limestone plateaus, as for example an unfinished T-Pillar with a size of about 7 m and volume of 20 m3 illustrates. Thus, the numbers given here may be in need of some extrapolation when projecting them onto about a dozen of such pillars forming one enclosure, especially considering the amount of time groups of hunters may have been able to invest. This suggests a certain degree of cooperation and organisation among several of such groups, since – apparently – a noteworthy number of people from the wider area had to be drawn together. A common mode for executing large communal tasks like this has been described under the term ‘collective work events’, usually achieved through the prospect of a lavish feast (Dietler and Herbich 1995). Gathering of work force may thus have been one motivation behind the large-scale feasting visible at Göbekli Tepe.

Conclusion: rather a sanctuary

Summing up, there seems to be enough evidence, with a checklist or without, to interpret Göbekli Tepe as a cultic place formed of special buildings with distinct and fixed life-cycles of building, use, deconstruction and burial. All of these stages seem to be marked by specific ritual acts, of which the last, i.e. those related to burial and deposition of symbolic objects are best visible archaeologically.

What remains is largely a problem of adequate terminology to address these buildings and the site as a whole. If ‘temple’ is understood as a technical term for specialised cult architecture, one could use it for Göbekli Tepe. If the term is defined in our western perception as a place where a god is present, ‘sanctuary’ would maybe be a more neutral description; alternatively the auxiliary construction ‘special buildings’ (Sondergebäude) could be used to escape any trap of culturally bound denominations. But in any case one thing is sure: the idea that Göbekli’s buildings are ‘so fair houses’ is not supported by the evidence available so far.

Notes

1 The site of Göbekli Tepe is excavated since 1995 under the direction of Klaus Schmidt as a research project at the German Archaeological Institute (DAI), from 2003 onwards funded with support of the German Research Foundation (DFG). Both authors are involved in this research project since 2005 resp. 2006 and would like to thank Klaus Schmidt for the opportunity to participate in the project. Furthermore we would like to express our gratitude to the General Directorate of Antiquities of Turkey for the kind permission to excavate this important site. Originally, Klaus Schmidt would have liked to take a position towards Banning’s (2011) interpretation of the site (see below) himself, but due to scheduling conflicts he could not participate in the preparation of this paper.

2 Layer II had been subdivided preliminarily during excavation work in IIa and IIb as in some surface-near areas also small round building structures have been documented. Their layout clearly differs from the usual rectangular buildings and there are some indications that they are considerably older. As the character of these buildings, which maybe belong to a fourth layer, has not been understood completely yet, the former labels IIa and IIb have been waived, as they implied a close relation between the buildings. Layer II refers exclusively to the rectangular building phase.

3 For an attempt at reconstructing PPN beliefs based partly on ethnographic evidence from New Guinea see Verhoeven 2002.

4 Of course it is in no way intended to draw direct conclusions from spiritual life in New Guinea for the PPN here. Completely different examples could have been used, but it seems nevertheless more consequent to draw on material that seems to relate in certain aspects to the material culture studied archaeologically.

5 Personal communication Tristan Carter, Toronto.

Bibliography

Banning, E. B. (2011) So Fair a House: Göbekli Tepe and the Identification of Temples in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic of the Near East. Current Anthropology 52/5, 619–660.

Becker, N., Dietrich, O., Götzelt, T., Köksal-Schmidt, Ç., Notroff, J. and Schmidt, K. (2012) Materialien zur Deutung der zentralen Pfeilerpaare des Göbekli Tepe und weiterer Orte des obermesopotamischen Frühneolithikums. Zeitschrift für Orient-Archäologie 5, 14–43.

Benedict, P. (1980) Survey Work in Southeastern Anatolia. In H. Çambel, and R. J. Braidwood (eds) İstanbul ve Chicago Üniversiteleri karma projesi güneydoğu anadolu tarihöncesi araştırmaları – The Joint Istanbul – Chicago Universities Prehistoric Research in Southeastern Anatolia, 150–191. Istanbul: University of Istanbul, Faculty of Letters Press.

Bertemes, F. and Biehl, P. F. (2001) The Archaeology of Cult and Religion: An Introduction. In P. F. Biehl, F. Bertemes and H. Meller (eds) The Archaeology of Cult and Religion, 11–24. Budapest, Archaeolingua.

Biehl, F., Bertemes, F. and Meller, H. (ed. 2001) The Archaeology of Cult and Religion. Budapest, Archaeolingua.

Bodet, C. (2011) The megaliths of Göbekli Tepe as a standing statement of Neolithic kinship structures. Peneo 3/1, 1–15. «http://www.ifea-istanbul.net/website_2/images/stories/archeologie/peneo/gobekli.pdf» (23.08.2011).

Bucak, E. and Schmidt, K. (2003) Dünyanın en eski heykeli. Atlas 127, 36–40.

Cauvin, J. (1994) Naissance des divinités, naissance de l’agriculture. Paris, Editions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

Çelik, B. (2000) An Early Neolithic Settlement in the Center of Şanlıurfa, Turkey. Neo-Lithics 2–3, 4–6.

Cranstone, B. A. L. (1971) The Tifalmin: A ‘Neolithic’ People in New Guinea. World Archaeology 3/2, 132–142.

Cutting, M. (2007) Wandmalereien und -reliefs im anatolischen Neolithikum. Die Bilder von Çatal Höyük. In Vor 12000 Jahren in Anatolien. Die ältesten Monumente der Menschheit, 246–257. Stuttgart, Theiss Verlag.

Dietler, M. and Herbich, I. (1995) Feasts and labor mobilization. Dissecting a fundamental economic practice. In M. Dietler and B. Hayden (eds) Feasts. Archaeological and ethnographic perspectives on food, politics, and power, 260–264. Washington, DC & London, Smithsonian Institution Press.

Dietrich, O. (2011) Radiocarbon dating the first temples of mankind. Comments on 14C–dates from Göbekli Tepe. Zeitschrift für Orient-Archäologie 4, 12–25.

Dietrich, O. and Schmidt, K (2010) A Radiocarbon Date from the Wall Plaster of Enclosure D of Göbekli Tepe. Neo-Lithics 2, 82–83.

Dietrich, O., Heun, M., Notroff, J., Schmidt, K. and Zarnkow, M. (2012) The Role of Cult and Feasting in the Emergence of Neolithic Communities. New Evidence from Göbekli Tepe, South-eastern Turkey. Antiquity 86, 674–695.

Eliade, M. (1959) The Sacred and the Profane. New York, Brace & World.

Epstein, A. L. (1999) Tolai Sorcery and Change. Ethnology 38/4, 273–295.

Garfinkel, Y. (2003) Dancing at the Dawn of Agriculture. Austin, University of Texas Press.

Gebel, H. G. K., Hermansen, B. D. and Hoffmann Jensen, C. (eds) (2002) Magic Practices and Ritual in the Near Eastern Neolithic. Berlin, ExOriente.

Hauptmann, H. (1988) Nevalı Cori: Architektur. Anatolica XV, 99–110.

Hauptmann, H. (1993) Ein Kultgebäude in Nevalı Cori. In M. Frangipane, H. Hauptmann, M. Liverani, P. Matthiae and M. Mellink (eds) Between the Rivers and Over the Mountains. Archaeologica Anatolica et Mesopotamica Alba Palmieri dedicata, 37–69. Rome, Università di Roma “La Sapienza”.

Hauptmann, H. (1999) The Urfa Region. In M. Özdoğan and N. Başgelen (eds), Neolithic in Turkey, 65–86. Istanbul, Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yayınları.

Hauptmann, H. (2003) Eine frühneolithische Kultfigur aus Urfa. In M. Özdoğan, H. Hauptmann and N. Başgelen (eds), Köyden Kente. From village to cities. Studies presented to Ufuk Esin, 623–636. Istanbul, Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yayınları.

Hawkes, C. (1954) Archaeological Theory and Method: Some Suggestions from the Old World. American Anthropologist 56/2, 155–168.

Herrmann, R. A. and Schmidt, K. (2012) Göbekli Tepe-Untersuchungen zur Gewinnung und Nutzung von Wasser im Bereich des steinzeitlichen Bergheiligtums. In F. Klimscha, R. Eichmann, C. Schuler and H. Fahlbusch (eds) Wasserwirtschaftliche Innovationen im archäologischen Kontext, 57–67. Rahden, Verlag Marie Leidorf.

Hodder, I. (ed.) (2010) Religion in the Emergence of Civilization: Çatalhöyük as a Case Study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hodder, I. and Meskell, L. (2011) A “Curious and Sometimes a Trifle Macabre Artistry”. Some Aspects of Symbolism in Neolithic Turkey. Current Anthropology 52/2, 235–263.

Hoskins, J. A. (1986) So My Name Shall Live: Stone-Dragging and Grave-Building in Kodi, West Sumba. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 142/1, 31–51.

Insoll, T. (2004) Archaeology, Ritual, Religion. London and New York, Routledge.

Insoll, T. (ed.) (2011) The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Ritual and Religion. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Kelm, (2011) Schädelmasken aus Neubritannien. In A. Wieczorek and W. Rosendahl (eds) Schädelkult. Kopf und Schädel in der Kulturgeschichte des Menschen. Regensburg: Schnell und Steiner.

Koch, G. (1982) Geister in Stein. Die Berliner Iniet-Figuren-Sammlung. Berlin, Museum für Völkerkunde.

Kolb, M. J. (2011) The Genesis of Monuments in Island Societies. In M. E. Smith (ed.) The Comparative Archaeology of Complex Societies, 138–164. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Konrad, G. and Biakai, Y. (1987) Zur Kultur der Asmat. Mythe und Wirklichkeit. In M. Münzel (ed.) Neuguinea. Nutzung und Deutung der Umwelt, 465–509. Frankfurt am Main, Museum für Völkerkunde.

Kroll, H. (1937) Der Iniet. Das Wesen eines melanesischen Geheimbundes. Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 69, 180–220.

Kyriakides, E. (ed.) (2007) The Archaeology of Ritual. Los Angeles, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press.

Michel, T. (1988) Kulthäuser als ökologische Modelle, Star Mountains von Neuguinea. Paideuma 34, 225–241.

Moetz, F. K. and Çelik, B. (2012) T-shaped Pillar Sites in the Landscape around Urfa. In R. Matthews and J. Curtis (eds) Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. Volume 1: Mega-cities & Mega-sites, 665–709. Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz Verlag.

Morsch, M. (2002) Magic Figurines? Some Remarks about the Clay Objects of Nevali Cori. In H. G. K. Gebel, B. D. Hermansen and C. Hoffmann Jensen (eds) Magic Practices and Ritual in the Near Eastern Neolithic, 145–162. Berlin, ExOriente.

Mückler, H. (2009) Kult und Ritual in Melanesien. Geheimbünde, Rangordnungsgesellschaften, Cargo und Kula. In H. Mückler, N. Ortmayr and H. Werber (eds), Ozeanien. 18. bis 19. Jahrhundert. Geschichte und Gesellschaft, 164–189. Wien, Promedia.

Neef, R. (2003) Overlooking the Steppe-Forest: A preliminary Report on the botanical Remains from Early Neolithic Göbekli Tepe. Neo-Lithics 2, 13–16.

Notroff, J., Dietrich, O. and Schmidt, K. (2014) Building Monuments – Creating Communities. Early monumental architecture at Pre-Pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe. In J. Osborne (ed), Approaching Monumentality in the Archaeological Record, 83–105. Albany, SUNY Press.

Özdoğan, A. (1999) Çayönü. In M. Özdoğan and N. Başgelen (eds), Neolithic in Turkey, 35–63. Istanbul, Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yayınları.

Özdoğan, A. and Özdoğan, M. (1998) Buildings of Cult and Cult of Buildings. In G. Arsekük, M. Mellink W. Schirmer (eds) Light on Top of the Black Hill – Studies presented to Halet Çambel, 581–602. Istanbul, Ege Yayınları.

Özkaya, V. and San, O. (2007) Körtik Tepe. Bulgular ışığında kültürel doku üzerine ilk gözlemler. In M. Özdoğan and N. Başgelen (eds), Türkiye’de neolitik dönem: 21–36. Istanbul: Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yayınları.

Pavel, P. (1990) Reconstruction of the Transport of Moai. In H.-M. Esen-Bauer (ed.) State and Perspectives of Scientific Research in Easter Island Culture, 141–144. Frankfurt am Main, Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg.

Peters, J., von den Driesch, A., Pöllath, N. and Schmidt, K. (2005) Birds in the megalithic art of Pre-Pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, Southeast Turkey. In G. Grupe and J. Peters (eds) Feathers, Grit and Symbolism. Birds and Humans in the Ancient Old and New Worlds, 223–234. Rhaden, Verlag Marie Leidorf.

Pétrequin, P. and Pétrequin, A.-M. (1993) Écologie d’un outil: la hache de pierre en Irian Jaya (Indonésie). Paris, CNRS Editions.

Renfrew, C. (1985) The Archaeology of Cult. London, Thames and Hudson.

Renfrew. C. (1994) The Archaeology of Religion. In C. Renfrew and E. B. W. Zubrow (eds) The Ancient Mind. Elements of Cognitive Archaeology. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Renfrew, C. (2007) The Archaeology of Ritual, of Cult, and of Religion. In E. Kyriakides (ed.) The Archaeology of Ritual, 109–122. Los Angeles, The Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press.

Roscoe, P. and Telban, B. (2004) The People of the Lower Arafundi: Tropical foragers of the New Guinea Rainforest. Ethnology 43/2, 93–115.

Schirmer, W. (1988) Zu den Bauten des Çayönü Tepesi. Anatolica XV, 139–159.

Schirmer, W. (1990) Some Aspects of Building at the ‘Aceramic-Neolithic’ Settlement of Çayönü Tepesi. World Archaeology 21/3, 363–387.

Schmidt, K. (1997) “News from the Hilly Flanks”. Zum Forschungsstand des obermesopotamischen Frühneolithikums. Archäologisches Nachrichtenblatt 2/1, 70–79.

Schmidt, K. (1998) Frühneolithische Tempel. Ein Forschungsbericht zum präkeramischen Neolithikum Obermesopotamiens. Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 130, 17–49.

Schmidt, K. 2001. Göbekli Tepe, Southeastern Turkey. A preliminary Report on the 1995–1999 Excavations. Paléorient 26/1, 45–54.

Schmidt, K. (2005) Die “Stadt” der Steinzeit. In H. Falk (ed.), Wege zur Stadt – Entwicklung und Formen urbanen Lebens in der alten Welt, 25–38. Bremen, Hempen.

Schmidt, K. (2006) Sie bauten die ersten Tempel. Das rätselhafte Heiligtum der Steinzeitjäger. Die archäologische Entdeckung am Göbekli Tepe. München, C. H. Beck.

Schmidt, K. (2008) Die zähnefletschenden Raubtiere des Göbekli Tepe. In D. Bonatz, R. M. Czichon and F. Janoscha Kreppner (eds), Fundstellen. Gesammelte Schriften zur Archäologie und Geschichte Altvorderasiens ad honorem Hartmut Kühne, 61–69. Berlin: Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz Verlag.

Schmidt, K. (2010) Göbekli Tepe – the Stone Age Sanctuaries. New results of ongoning excavations with a special focus on sculptures and high reliefs. Documenta Praehistorica 37, 239–256.

Schmidt, K. (2012) Göbekli Tepe. A Stone Age Sanctuary in South-Eastern Anatolia. Berlin, ExOriente.

Schmidt, K. (2013 Von Knochenmännern und anderen Gerippen – zur Ikonographie halb- und vollskelettierter Tiere und Menschen in der prähistorischen Kunst. In Th. Uthmeier (ed.) Gedenkschrift für Wolfgang Weißmüller, 195–201. Büchenbach, Verlag Dr. Faustus.

Schröder, E. E. W. (1917) Nias, ethnographische, geographische en historische aanteekeningen en studien. Leiden: Brill.

Silitoe, P. and Hardy, K. (2003) Living Lithics: Ethnoarchaeology in Highland Papua New Guinea. Antiquity 77, 555–566.

Stanek, M. (1987) Die Männerhausversammlung in der Kultur der Iatmul (Ost-Sepik-Provinz, Papua Neuguinea). In M. Münzel (ed.) Neuguinea. Nutzung und Deutung der Umwelt, 621–643. Frankfurt am Main, Museum für Völkerkunde.

Stöhr, W. (1987) Die Religionen Neuguineas. In M. Münzel (ed.) Neuguinea. Nutzung und Deutung der Umwelt, 419–462. Frankfurt am Main, Museum für Völkerkunde.

Stordeur, D. (2000) New discoveries in architecture and symbolism at Jerf el Ahmar (Syria), 1997–1999. Neo-Lithics 1, 1–4.

Stordeur, D., Brenet, M., der Aprahamian, G. and Roux, J. C. (2000) Les bâtiments communautaires de Jerf el Ahmar et Mureybet horizon PPNA (Syrie). Paleórient 26/1, 29–44.

Van Tilburg, J. A. and Ralston, T. (2005) Megaliths and Mariners: Experimental Archaeology on Easter Island. In K. L. Johnson (ed.) Onward and Upward: Papers in Honor of Clement W. Meighan, 279–306. Chico, CA, Stansbury Publishing.

Verhoeven, M. (2002) Ritual and Ideology in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B of the Levant and Southeast Anatolia. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 12/2, 233–258.

Zöllner, S. (1977) Lebensbaum und Schweinekult. Darmstadt, Theologischer Verlag Rolf Brokhaus.