Communal places of worship: ritual activities and ritualised ideology during the Early Bronze Age Jezirah

Introduction

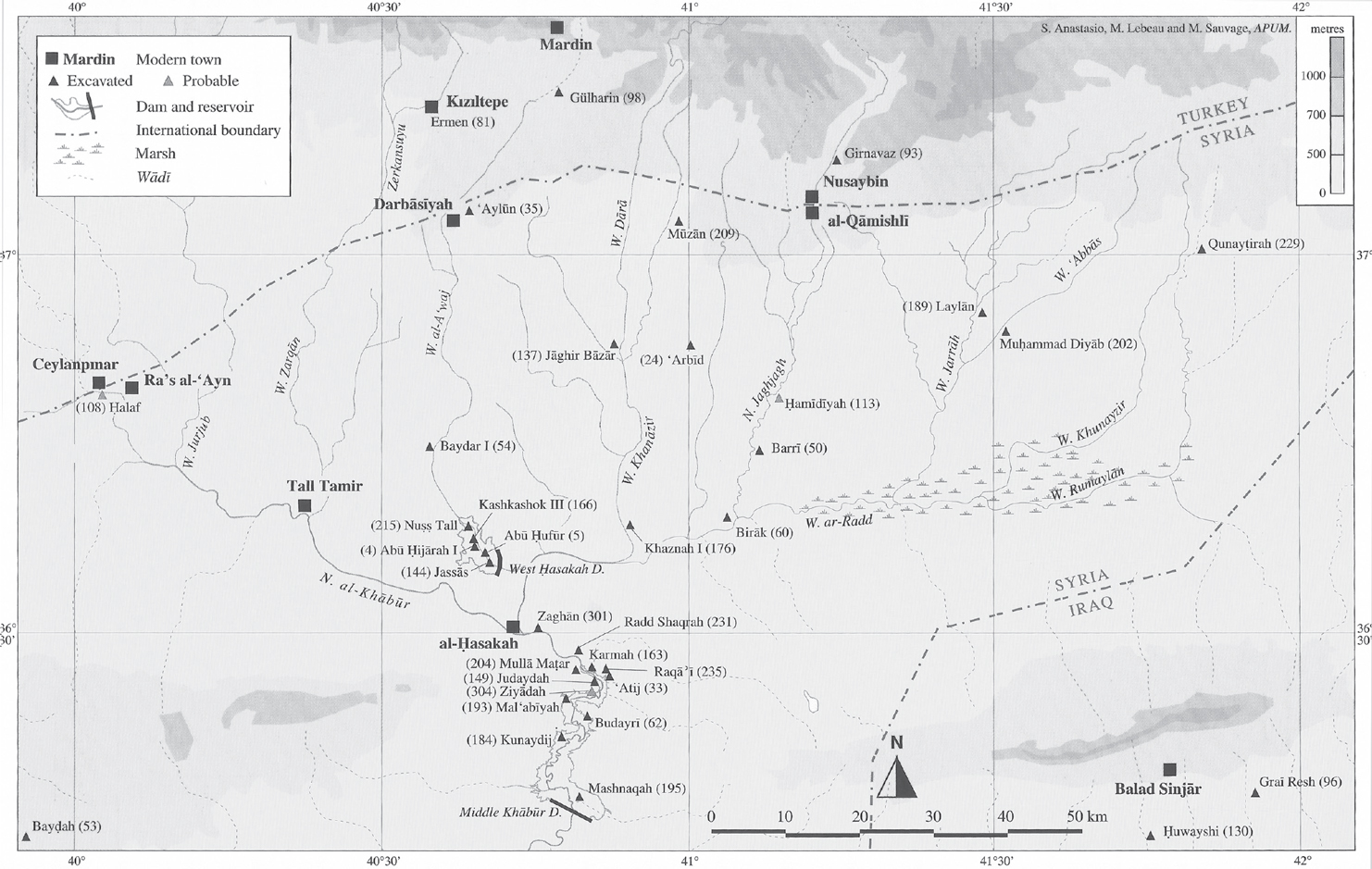

The spread of communal places of worship in the Jezirah (Fig. 9.1)1 is strongly related to the phenomenon of the regeneration of complex society that characterises the Upper Mesopotamia after the crisis of the Uruk system, at the end of the 4th millennium, and before the middle of the 3rd millennium BC (Schwartz 2006), which marks the peak period of the Jezirah civilisation, coinciding with the so-called Second Urban Revolution (Lebeau 2011b, 368–370) (Fig. 9.2).2 Here, I investigate how ritual practices are implicated in this process and their relationship with the Jezirah material culture through the analysis of the archaeological elements, more specifically, architecture and ritual objects.

Archaeological data

Architecture

If we consider the religious architecture in Jezirah, as Pfälzner has recently noted (2011, 177), there is not yet any evidence for the Early Jezirah 0 and 1 periods. Instead in the Early Jezirah 2 period, as the studies of Schwartz (2000) and Matthews (2002) have demonstrated, a series of small shrines are attested.

The first discovered was that of Level 3 at Raqa’i (Curvers and Schwartz 1990). It is a freestanding Single-Roomed-Shrine (5 × 4.5 m) erected within an open courtyard surrounded by an enclosure wall (Fig. 9.3). The cella is a bent axis room accessed through a door framed by buttresses. Inside the room there is a bench, an altar with steps, and traces of a fireplace in the center of the floor. Behind the cella, there are two small rooms, where various activities relating to the shrine probably took place.

A Single-Roomed-Shrine (8 × 4.5 m) was also excavated at Brak (Matthews 2003) in level 5 (HS4 building). The position of the entrance is unclear, and the room contains benches along one long and one short side (Fig. 9.3). A freestanding box altar is located along the central axis, and a fireplace is set in front of it on the floor. The level 4 rebuilding was performed after the old room had been intentionally filled with clean soil.

Another example of a freestanding Single-Roomed-Shrine is a building (8 × 6 m) excavated at Kashkashouk III (Suleiman and Taraqji 1995, 179–181). It presents a bent axis entrance with recessed internal entry. Inside the room, along the W side, there is an altar provided with buttresses. Two benches are located along the north and west sides (Fig. 9.3).

The Chagar Bazar example of an early shrine is problematic. Mallowan (1936, 15) interpreted room 1 of level 4 as a Single-Roomed-Shrine, with a recessed entry (Fig. 9.3), but there are few elements to confirm this hypothesis.

The ‘Atij building (Fig. 9.3) was considered by Matthews (2002, 188) as a possible example of Single-Roomed-Shrine, but there are no elements to confirm this hypothesis. Fortin and Cooper (1994), the excavators, interpreted this room as a house.

At Khuera, in the Kranzhugel region, on the western border of the Jezirah, the Kleiner Anten-Tempel attests to this presence of this type of religious architecture (Levels 5–4, Early Jezirah 2 Final–3a) (Pfälzner 2011, 183–187). The cella was accessible through a court/corridor and contains a fireplace, a bench and a steps altar (Fig. 9.3). An important difference with respect to the other shrines, however, is that we are not in a freestanding building – since the shrine was embedded in the dwelling – and that the room was accessible by a frontal entry. This peculiarity seems to anticipate the solution adopted in the proper Anten-Tempel of level 1–3, dating to the Early Jezirah 3b and built directly above the structures of level 4. In contrast to Moortgat (1967, 28–32) and Orthmann (1990), the excavator, Pfälzner (2011, 186–187) interpreted phases 4 and 5 of this building as a house with an ancestor altar, and phases 1–3 as an ancestor shrine. He compares the Kleiner Anten-Tempel (Levels 5–4) to House IIa, excavated in Area K at Khuera (Dohmann-Pfälzner and Pfälzner 1996). The main room of the house, accessible from a courtyard/corridor, is located on the back of the complex and equipped with a rounded hearth, an altar or podium, and benches along the walls. According to Pfälzner (2011, 152 and 177) this is another Khuera-type house with an ancestor altar or at most a small shrine for the family’s ancestors.

The so-called Southern Temple of Arbid (Bieliński 2010) was a rectangle room (8 × 4.5 m) with a bent axis arrangement that includes a finely plastered altar with grooves (Fig. 9.3). A square hearth was located in front of it. On the floor, close to the altar, a nearly complete incense burner, in the shape of a small column, was found. A freestanding partition wall separated the main cella from a kind of sacristy, and to the north and west of the cella there is a rooms interpreted as a granary. The building appears to have been cleared before it was abandoned. The Southern Temple was erected on a mud-brick platform; thus it seems that the builders sought to create an impressive visual approach. The Arbid ritual complex is the best know example of a temple built on the top of a terrace in Early Jezirah 2 period architecture.

Fig. 9.1: Map of Jezirah (Lebeau 2011a, modified).

Fig. 9.2: Chronology of Jezirah in the Early Bronze age (Lebeau 2011b, 380).

The Early Jezirah 2 Monumental Temple of Mozan/Urkesh (Fig. 9.3), located on the high tell in the city’s centre, constitutes the only other example of this type (Dohmann-Pfälzner and Pfälzner 1999). The existence of a mud-brick ramp substructure leading up to the high mud-brick terrace is clear (so-called Stage I, Pfälzner 2011, 179). In Early Jezirah 2 there is no evidence that the stone-built, oval temenos wall that appears in the Early Jezirah 3 period was yet present (Stage II, Pfälzner 2011, 179, fig. 53) and the exact layout of the temple on top of the terrace is not known, although it can be hypothetically assumed that the Early Jezirah 3 cella already existed in this period.

At Khazna the monumental complex (Munchaev and Merpert 1994; Munchaev et al. 2004, 477) – a dense cluster of rectangular rooms excavated on the top of the hill and surrounded by a thick fortification wall – has tentatively been interpreted by the excavators as a religious-administrative complex (Fig. 9.3). In particular Buildings 136 and 69 may be temples, but due to the unclear stratigraphy and the lack of religious installations, Pfälzner (2011, 197) interprets the Khazna architecture as a huge communal storage complex.

Before concluding this overview of the religious architecture of the Early Jezirah 2 period, we must consider the Sacred Area of Tell Barri, excavated between 2002 and 2005 (Pecorella and Pierobon 2003; 2005a; Valentini 2006–2007).

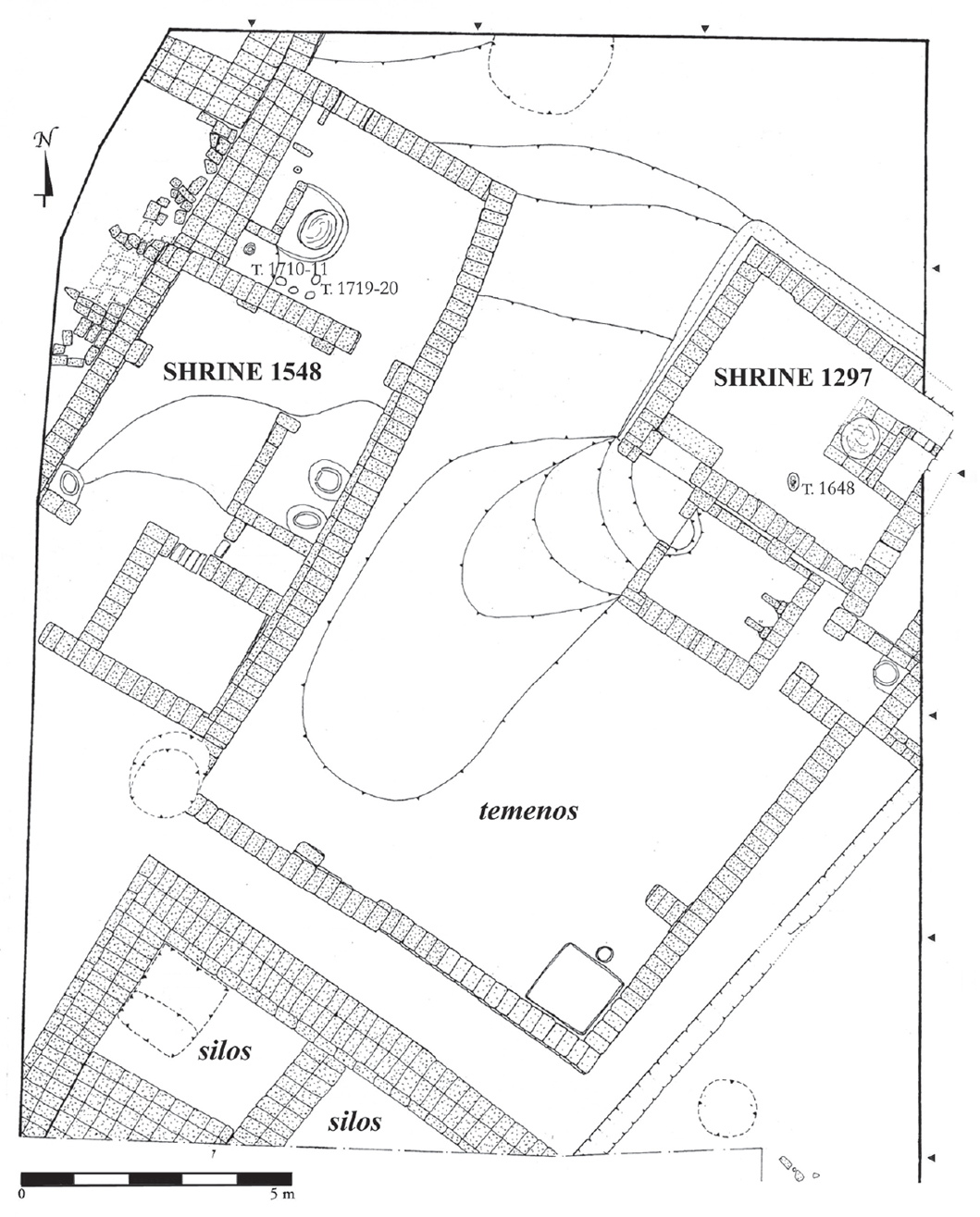

At Barri, a long sequence of strata with domestic and storage installations was excavated in Area B. This sequence starts at the very beginning of the 3rd millennium, in the Early Jezirah 0, and continues until the Early Jezirah 2 period, when the Barri settlement expands from the west to the southeast slope. Here, in Area G, a Sacred Area (Fig. 9.4), dating to the Early Jezirah 2 (stratum 44), was built ex novo directly above virgin soil in a sector previously not inhabited. The complex was constituted by two buildings interpreted as temples, a large open space, a temenos, and a storage building comprising two siloi.

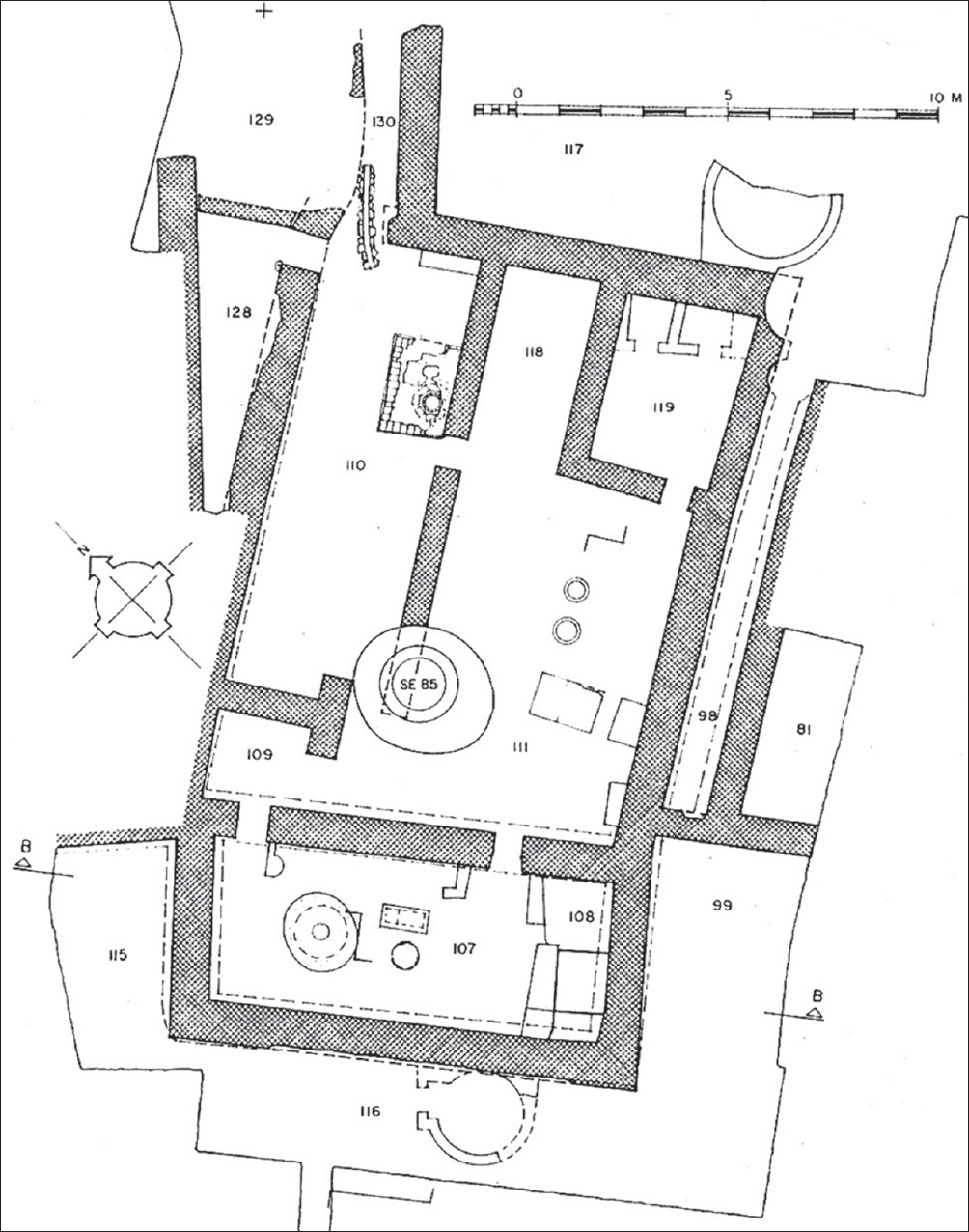

Fig. 9.3: Plans of Jezirah Communal places of worship (Redrawn after Matthews 2002, fig. 1; 2003; Curvers and Schwartz 1990; Suleiman and Taraqji 1995; Mallowan 1936; Moortgat 1967; Bieliński 2010; Pecorella and Pierobon 2005a; Fortin and Cooper 1994; Munchaev et al. 2004; Pfälzner 2011).

The single Shrine 1297 (Fig. 9.5) was a rectangular room with a bent axis arrangement that was isolated inside the temenos above a mud-bricks platform filled with clean soil. It presents a recessed entry and buttresses on the façade. On the short side, a box altar with grooves stood, and in front of it there lay a small bench with an oval fireplace. The presence of the fireplaces indicates that food offerings, probably contained in small pottery vessels, were burnt within the shrines. The box-altar was probably covered by a wooden table and may have been open on the short side so that it could be used for ritual presentation, to store offerings, and to display animal and human clay figurines.

Under the beaten floor, inside a small pit, three incomplete skeletons of one fetus and two newborns were buried. The room was accessible through a small ramp where the entrance to a small kitchen with a fireplace – the so-called Sacristy – was also located. Shrine 1548 (Fig. 9.6) was a Multi-Roomed Complex. The cella was accessible from a court in which a kitchen with two tannurs and two small storage rooms were located. As in the other shrine, the short side of the cella had a box altar, and in front of it there was a small bench with a semicircular fireplace. Under the beaten floor, four small pits yielded eight incomplete skeletons of fetuses and newborns.

Newborns and fetus intra muros burials are quite common in Jezirah during the first half of the 3rd millennium, but there are no known examples of burials from inside temples. There are two elements that make the Barri burials even more anomalous (Valentini 2009; 2011). First they are pit burials, while most of the newborns in this period are buried in pottery vessels. Secondly they are multiple and progressive burials, while most of the newborn burials in this period are normally single inhumation. In fact each pit normally contains a complete skeleton – probably the last buried – which was added to other incomplete skeletons (Sołtysiak 2008). If we postulate that these rural shrines were an expression of a religious system in an agricultural community, in which seasonal rites are performed with the aim of ensuring good harvests, we can speculate that the burials inside the shrines were symbolically related to the concept of fertility. Perhaps the dead individual was perceived as part of a complex system of debt to the earth, with his death working to assure the fertility of the field. Although there is a lack of textual reference on human sacrificial practices of newborns, a priori, the possibility of foundations rituals or propitiatory inhumations cannot be excluded.3

Fig. 9.4: Barri Sacred Area, stratum 44 (Pecorella and Pierobon 2005b, fig. 1. Modified).

The Sacred Area underwent changes over time (Pecorella and Pierobon 2005a, fig. 1). For example, in stratum 43 inside the temenos, a chicane route was created, probably to provide a kind of processional way during ritual celebrations. Later, in stratum 42, Shrine 1548 was abandoned and replaced with a big open space with two pairs of rooms overlooking the court. During the last phase of Shrine 1297, in stratum 40, the walls of the old room were tiled and covered with new walls and, after a deliberate filling with clean soil of the remaining space, a new building, with the same plan, was built on top. The old altar was reutilised as a pit and a new fireplace was placed in the southeast corner.4

As demonstrated by the archaeological evidence, the Sacred Area of Barri – the only example in the Jezirah during the Early Jezirah 2 period – shows the coexistence of two different kinds of religious architecture, the Single-Roomed Shrine (1297) (Fig. 9.5) and the Multi-Roomed Complex (1548) (Fig. 9.6), at the same time in the same context.

In particular, the Barri Multi-Roomed Complex (Figs 9.4, 9.6) encourages further investigation into the possible relationship between the Jezirah and Lower Mesopotamian religious architecture, firstly posited by Schwartz (2000).5 When compared with the Sin Temple (Level VII) of Khafajah (Fig. 9.7), for example, the Barri building resembles a downscaled version of contemporary urban Mesopotamian temples. This is even more evident when the plan of the Barri Shrine 1548 is juxtaposed with contemporary Nippur North Temple (Fig. 9.8). The similarities are remarkable: the cella is located on the opposite side of the entrance, and part of the building is occupied by a court, which other rooms, including kitchens and storage rooms, overlook.

Fig. 9.5: Barri Sacred Area, Shrine-Roomed Shrine 1297 (Archive of the Archaeological Mission at Tell Barri).

Fig. 9.6: Barri Sacred Area, Multi-Roomed Complex 1548 (Archive of the Archaeological Mission at Tell Barri).

When considering the Jezirah Communal Places of Worship as an assemblage, it is difficult to escape the impression that the builders chose from a recurrent menu of architectural elements. Although most of the elements of the Jezirah buildings derived from a domestic context, their specific arrangement in these contexts represents a clear example of formal architecture adopted for religious purposes. The ritual preparation of foundations, as demonstrated by the Barri and Raqa’i examples, confirms the sacred nature of this architecture. The pit foundation was filled with clean, pure soil, stacks of bricks, or have walls marking their perimeter with the temple proper built on top of this platform. Moreover, as the shrines of Barri, Brak and Raqa’i demonstrate, before the construction of a new temple, the old one was deliberately filled, probably for symbolic and ritual reasons. Finally, the fetus burials excavated inside the Barri shrines that were probably linked with rituals foundation must not be forgotten within this broader context.

Furthermore the platforms of Arbid and Mozan – and to a lesser extent, Barri – demonstrate that the temple was conceived as a separate entity. This is confirmed by the presence of the temenos – what Schwartz (2000) terms the so-called Precinct – as in the case of Barri, Raqai, Mozan and Kashkashok. The enclosure wall isolated the temple from the rest of the buildings, and enabled the control of public access to the sacred area.

Fig. 9.7: Khafajah, Sin Temple, Level VII (Delougaz and Lloyd 1942, pl. 9).

In summary, this survey of the Jezirah religious architecture dating to the Early Jezirah 2 period demonstrates the existence of four main architectural types (Fig. 9.3):

• Single-Roomed Shrine: Raqa’i, Brak, Kashkashouk, Chagar Bazar (?), ‘Atij (?), Arbid, Barri;

• Multi-Roomed Complex: Barri;

• Proto Anten-Temple with frontal entry: Khuera;

• Monumental Temple on high terrace: Mozan, Hazna (?).

The incredible amount of information that has emerged from recent excavations in the Jezirah thus allows us to define, sometimes in unexpected was, the direct filiation and continuity between the religious architecture of the Early Jezirah 2 period and that of the large urbanised centers of the second half of the 3rd millennium (Early Jezirah 3 period). In this context, the similarities between the Single-Shrine with a bent axis arrangement of Brak and the Temple BA of Mozan (Buccellati and Kelly-Buccellati 1988), and between the Multi-Roomed complex of Barri and the Early Jezirah 3 Temples B and C of Beydar (Lebeau 2006) are particularly striking. Regarding the Khuera Anten-Temple with a frontal entry, there is clear stratigraphical evidence of continuity between the Proto Anten-Temple (level 4–5) and the Anten-Temple (level 1–3), as well as with the later monumental architecture of the Steinbau I–III and VI (Pfälzner 2011, 184–185).6 Finally, as regards the South Mesopotamian-style of high terrace temple, as Pfälzner (2011, 189–190) terms it, clear continuity is attested between Stage I and Stages II and III of the Oval Temple of Mozan.

Ritual objects

As we move from architecture to ritual objects, we will primarily consider the significant repertoire of material that was found in the Sacred Area of Barri (Valentini 2008a). Although not all of these are ritual objects per se, it is often possible to deduce their function from the archaeological context and reconstruct how they may have been used in the cult.

First of all the hand-made miniature stands must be considered (Fig. 9.9). These stands were probably utilised inside the shrines, during the rituals, as supports for bowls and cups containing food offerings.

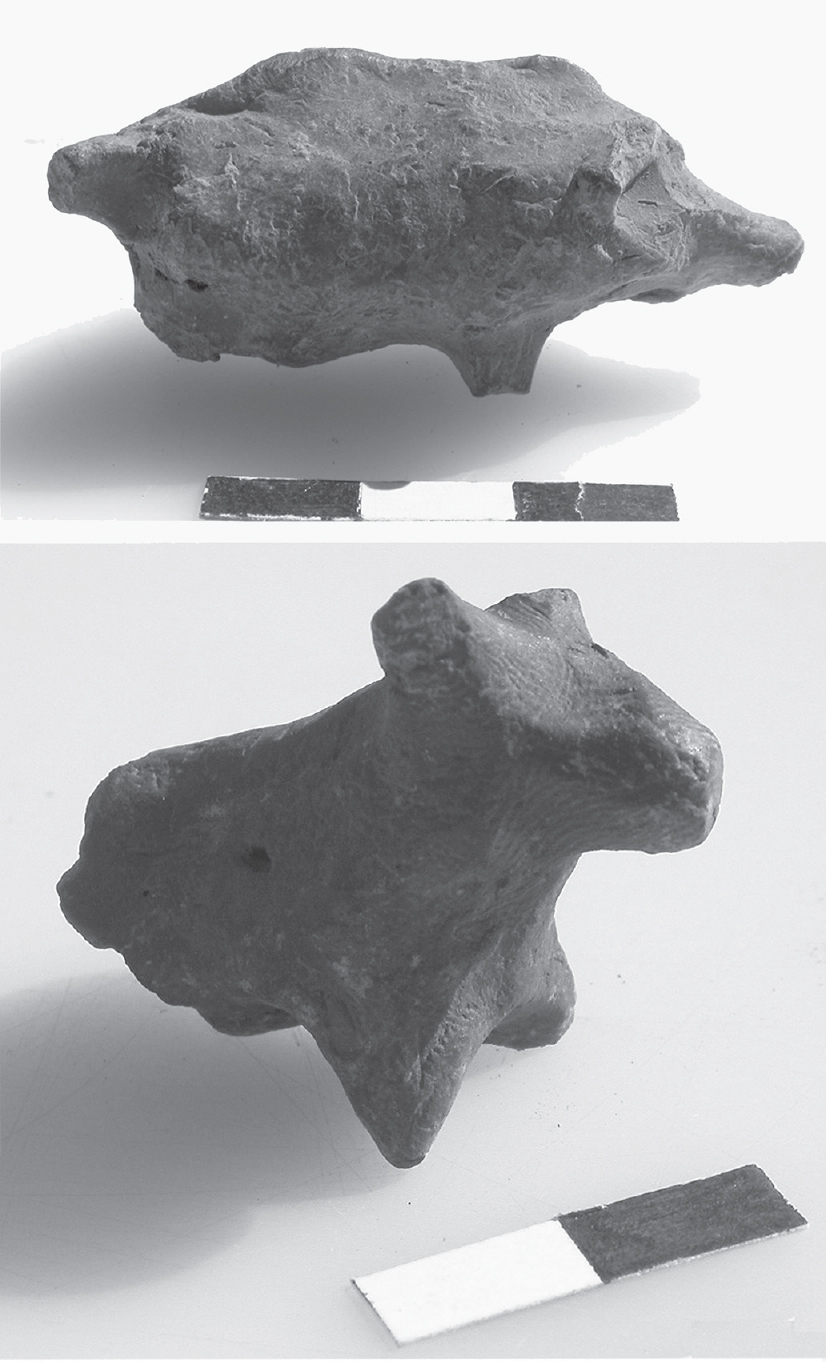

Then the significant number of fragmentary clay animal and human hand-made figurines coming from the Sacred Area must be emphasised. The human figures are minimalist and all the body elements are stylised and reduced to essential (Fig. 9.10). On the basis of the context, we can recognise these figurines as ritual, but the lack of any definite attributes or clear gestures prevents us from deciding where they are meant as representations of deities, votaries representing worshippers, or offerings in human form. A. Pruss (2011, 240) assumed that these figurines reflect an experimental stage in the production of clay images in which a growing anthropomorphism of the divine image is attested. The animal figurines – both cattle and sheep, except one wild boar (Fig. 9.11) – might be used as substitutes of food offerings during the rituals, or as tokens or amuletic receipts provided in exchange for ritual animal sacrifices (Liebowitz 1988). Additionally, the discovery of clay cartwheels, which may indicate the use of model vehicles for the rituals, is interesting. Most of these objects seem to have been deliberately broken during or after use.7

Other peculiar objects include the portable hearts and the andirons (Fig. 9.12). These low-fired ceramic objects belong to three different categories: the horseshoe shaped type (A), the snouted shaped type (B), and the cylindrical shaped type (C). Two examples were found in Barri on the floor of the Shrine 1297, so it can be assumed that they were used above the fireplaces. Other contemporary parallels come from Brak (Matthews 2003, 111), Arbid (Bieliński 2010) and Hazna (Munchaev and Merpert 1994, 41, fig. 29), and all were found in a ritual context. These objects shown significant similarities with examples coming from Anatolia, and the Jezirah examples may have been inspired by models originally produced in the Highlands (Valentini 2008a; Aquilano and Valentini 2010).8

Fig. 9.9: Barri Sacred Area, miniature stands (Archive of the Archaeological Mission at Tell Barri).

As regard the pottery vessels, in the Sacred Area at Barri the concentration of wares in which both aesthetics and ostentatious value coexist with a practical function must be stressed (Fig. 9.13); this is the case of the Ninevite 5 ware (Forest 1996), the Metallic ware, and especially for Jezirah Burnished ware (Valentini 2008b; Rova 2011, 70). This ware type is defined as pottery excavated in the Jezirah region, particularly at Barri and Arbid, with few other parallels (Smogorzewska 2009). In both cases, this pottery is strongly associated with religious architecture and its use in a ritual context may be related to its function as a medium that communicates a particular concept of identity to the community. As for the andirons, the connection with the Anatolian cultural horizon is also significant in this case.9

Finally, in the religious contexts of Barri (Valentini 2008a), Brak (Matthews 2003), Raqa’i (Curvers and Schwartz 1990), Khuera (Moortgat and Moortgat-Correns 1976) and Arbid (Bieliński 2010), it must be considered the relevant presence of administrative tools, such as tokens (Fig. 9.14) and seal impressions are also significant in this case (Fig. 9.15). The presence of door, jar and sack cretulae, which display animal and human figures, in a ritual context is important. Although the use of seals in this building may partly be explained by material reasons – in order to seal commodities used for the ritual activities and to control the access to the temenos and the religious building – it also has important ideological implications. In fact, the use of glyptic attests to the existence of an elite that controlled the ritual and economic activities linked with the temples and that, through the use of glyptic as status marker, transmitted political messages or propaganda. It is emblematic that in most of the seal impressions, the main figure was a man engaged in hunting, killing animals, holding a plough, or attending banquets or other ceremonies. These sealing impressions belong to a new local figurative style – clearly related to southern Mesopotamian models – that characterises the contemporary glyptic in most of the Jezirah settlements, and that is quite different from the earlier and standardised Piedmont Style (Parayre 2003).

Fig. 9.10: Barri Sacred Area, clay human figurine (Archive of the Archaeological Mission at Tell Barri).

Fig. 9.11: Barri Sacred Area, clay animal figurines (Archive of the Archaeological Mission at Tell Barri).

Fig. 9.12: Barri Sacred Area, andirons (Archive of the Archaeological Mission at Tell Barri).

Fig. 9.13: Barri Sacred Area, pottery (Archive of the Archaeological Mission at Tell Barri).

Fig. 9.14: Barri Sacred Area, tokens (Archive of the Archaeological Mission at Tell Barri).

Concluding remarks

After the collapse of the Late Uruk system, in the immediately subsequent period corresponding with the 1st quarter of the 3rd millennium (Early Jezirah 0–1), the Jezirah experienced a partial abandonment of settlements and a break down of regional economic system with a diffused ruralisation characterised by a subsistence economy based on small-scale farming (Akkermans and Schwartz 2003, 211–232; Lebeau 2011b). This scenario clearly begins to change in the Early Jezirah 2 period in which, according to Weiss (1990a; 1990b) and Schwartz (1994a; 1994b) the first signs of the regeneration process can be observed; a phenomenon that ended in the subsequent period (Early Jezirah 3a) in the middle of the 3rd millennium, with the advent of the Second Urban Revolution (Lebeau 2011b, 368–370). In the Jezirah, the disintegration of the old traditional socio-political and ideological structures seems to be part of a continuous process of reconstruction, in which new opportunities for social mobility and individual agency may emerge. Innovative elites, through competition, may find new avenues for the acquisition of power. The final Early Jezirah 2 period, to which the material culture discussed in this contribution can be ascribed almost entirely, represents the turning point of this phenomenon. By contextualising the archaeological data in their historical and cultural dimension, we can imagine the Jezirah settlements as inhabited by small communities in which elites controlled a local economic system based on the exploitation of surplus products from agricultural and stock-raising.10 Alongside these internal factors, trade may be a decisive external variable associated with this regeneration phenomemon. Elites could increase their power by establishing innovative, beneficial roles as intermediaries of a new system of long-distance trade between southern Mesopotamia and Anatolia.

Surplus derived from the political economy was invested to support elite projects, ranging from the building of shrines for collective ritual to craft activities, to developing and controlling ideological power. As demonstrated by the spread of shrines and the increase in ceremonial display and the consumption of ritual goods, the elite elaborated an intricate system of ritualised ideology to reinforce this new social order. But this new ideology, which was used strategically, might also have been materialised in order to become an effective source of power (DeMarrais et al. 1996). In this scenario once, according to Lebeau (2011, 369), a critical mass had been reached, leading to a new social and cultural system, there is clear evidence in the Jezirah for the spread of religious architecture and an escalation of ritual activities.

Fig. 9.15: Barri Sacred Area, sealing impression (Archive of the Archaeological Mission at Tell Barri).

The expansion and reorganisation of ritual could be interpreted as part of the effort to materialise, communicate and sustain new elite ideologies. As a consequence, the mobilisation of surplus by central authorities would be institutionalised in the form of religious rituals, making this activity part of the natural order of things.

Moreover, while the attestation of a formal religious architecture and the presence and the nature of some ritual objects might help to trace evidence for cultic activities, it is much more difficult to reconstruct their nature and the related religious beliefs, particularly considering the absence of cuneiform texts. Popular religious rituals, probably derived from household and ancestor practices, were probably performed at Khuera and in the smallest shrines. But Mozan, Arbid and the Sacred Area of Barri probably witnessed more structured rituals involving the whole community in an official and/or public capacity.11

This dichotomy between popular and official ritual and the similarities between the Diyala and the Jezirah regions encourages us to further investigate Forest’s (1996) hypothesis about the Khafajah Temples, in particular his hypothesis about the relationship of the smaller temples to the Temple Oval. The latter was undoubtedly the religious center of the city, both from a topographical and visual point of view. The smaller temples, in contrast, were located between the houses, and were hardly visible. Reflecting on the position of the Jezirah communal places of worship we realise that almost none of these lay at the heart of the settlement, instead, they, often lay practically at the foot of the mound, not in a visually dominant position. Only the monumental temple of Mozan – and the problematic building of Khazna – were located in the core of the settlement in a visible position. So this may be a situation similar to that encountered at Khafajah, where there may be both a central sanctuary, like the temple at Mozan, and a series of small satellite shrines, like those of Brak, Raqa’i or Barri. Furthermore, Forest (1996) hypothesised that the Khafajah temples could be used not only for a deity, but also for a deceased ancestor, or even for a man. As mentioned above, in the Jezirah, the archaeological evidence does not allow us to establishing securely to whom these buildings were dedicated. On one hand it can be assumed that the variability and combination of the architectural typologies were associated with the worship of different deities and different kinds of rituals. But on the other side it can be suggested, as a working hypothesis, that these buildings were multifunctional.12 And this second option may perhaps better characterise a series of relationships (for example between divinity and faithful, or elites and workers) and above all correspond to different contexts, including both sacred and secular. For this reason it is preferable to use the terminology of communal places of worship – rather than the more specific definitions as temple, shrine or sanctuary – because it can include all of these functional possibilities.

In conclusion, whilst we cannot understand all the different ways in which ‘rural-Jezirah versus urban-Mesopotamian elements’ (Schwartz and Falconer 1994) intermingled and overlapped with another, we can recognise places of worship as one of the products of this unique interplay, manifested in distinctive forms of artifacts and architecture.

Acknowledgements

This contribution is dedicated to Jean Daniel Forest, whose intuitions has helped spur my own reflections on the archeology of the religion of 3rd millennium Mesopotamia. Here I would also like to warmly thank Nicola Laneri with whom I shared the wonderful experience of excavation at the site of Hirbemerdon Tepe, during which, under the pergola of the expedition house, we have often discussed the topics covered in this paper.

Notes

1 The western and southern borders of the Jezirah are relatively clear: the Balikh and the Euphrates rivers to the west and the Syrian Desert to the south. Its northern limit, which corresponds to the Tur Abdin Mountains beyond the present Syro-Turkish border, is less defined, and is its Eastern limit, which divides the Jezirah from the Tigridian region, is a rather artificial one (Lebeau 2011a, 3–5).

2 In chronological terms, most of archaeological data considered in this paper refer to the Early Jezirah 2 period (2750–2550 BC), as defined in the ARCANE Project (Lebeau 2011b).

3 For an anthropological parallel see Bloch’s (1971) studies on the Merina community of Madagascar.

4 When the Sacred Area was abandoned in the Early Jezirah 3a period (stratum 39), the open space corresponding to the old temenos remained unbuilt. Two large complexes were constructed around it and a cist-tomb in mud-bricks and two shaft burials were excavated outside the buildings (Pecorella and Pierobon 2005b, 15–21, Valentini 2009). These tombs did not destroy the relationship with the previous phase of the temenos. On the contrary – as in the case of the Royal Tomb excavated in the destruction level of the Arslantepe Palace (Palumbi 2004) – a spatial continuity between the Sacred Area and the burials existed. The Barri’s nascent elite may have erected the burials in this ancient, sanctified place – the Sacred Area – to forge a link to the revered predecessors. To create a new memory the livings are obliged to consider their own past. This may represent a case of stimulus regeneration in which the mobilisation of social memory, that invokes their relations with kinship and the cycle of life and death provides these communities with the means to absorb change, and uphold continuity.

5 Concerning the Single-Roomed Shrine in Mesopotamia, there are few examples from the first half of the 3rd millennium. One of these is the Single Shrine in S44 at Khafajah (Delougaz and Lloyd 1942, fig. 105), but it is probably later than the Jezirah Shrines. An earlier example is the Archaic Shrine I of the Abu Temple at Tell Asmar (Delougaz and Lloyd 1942, pl. 19), but it is not a typical Single-room Shrine.

6 The Long-Roomed Temples in antis characterize the religious architecture of the Balikh and Euphrates region during the second half of the 3rd millennium (Akkermans and Schwartz 2003, 246–253).

7 The patterns of breakage can vary, although it was very common for human and animal figurines to have been broken at the neck. Because of their potency, cult figures are often carefully disposed of at the end of their use, but the overwhelming majority of Barri figurines were found in trash layers. A more persuasive suggestion is that the figurines represent vehicles of magic, and it is not uncommon for such artifacts to be deliberately broken (Petty 2004). The figurines may reference some concept or idea: the representation of a wild bull or a sheep does not have to symbolise the life of the animals or even the concept of the fertility of the herds, but could symbolize male virility among humans.

8 The rarity of these artefacts could confirm their important symbolic value. In Anatolia, these kinds of objects are usually associated with the Karaz Ware/Red-Black Burnished Ware and some scholars, on the basis of the interpretations of the Pulur anthropomorphic andirons, assign them ritualistic properties, although they are often found in domestic contexts (Takaoğlu 2000; Smogorzewska 2004). The andirons may be valued differently at the ends of the exchange network, especially because culturally different communities are involved. Objects made originally for utilitarian household rituals may have been incorporated into worship in the Jezirah ceremonial places.

9 A relationship between the Jezirah Burnished ware and the Red-Black Burnished ware can be hypothesised (Valentini 2008b). These two kinds of pottery show the same surface treatment and are attested in the same type of carinated bowls, as demonstrated by the examples excavated in the Upper Euphrates region at Korucutepe, Tepecik, Degirmentepe and Pulur. While the Red-Black Burnished ware was strictly hand made, the Jezirah Burnished ware was well shaped, and this could confirm its local production.

10 While is possible to identify clusters of settlements of varying sizes (big sites as Leilan and Brak, and small sites as Barri, Raqa’i, Kashkashouk) (Wilkinson and Tucker 1995), the aggregation of the settlements does not appear to exhibit rigid, hierarchical structures. This is not defined by central or core cities with all the administrative and organisational apparatus to govern and control the political, economic and religious affairs of the smaller, simpler, agro-pastoral communities that surrounded theme. On the contrary, we observe a more heterarchical web of settlements characterised by a dispersed arrangement of political, economic, and religious authority.

11 The presence at Barri of two shrines with different plans (a peculiarity as regards the other Jezirah sites) could be associated with the worship of two different deities.

12 As regard the definition of Jezirah shrines (Schwartz 2000: 167–170), Pfälzner (2001, 175 and 309; 2011, 177) asserts that this interpretation has been challenged.

Bibliography

Aquilano, M. and Valentini, S. (2011) Andirons and Portable Hearts in the Upper Tigris Valley. Paper presented at the Symposium, Archaeology of the Ilısu Dam (Mardin, Turkey – October 19th–22nd, 2011).

Akkermans, M. M. G. and Schwartz, G. M. (2003) The Archaeology of Syria. From Complex Hunter-gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c. 16,000–300 BC). Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Bieliński, P. (2010) Tell Arbid. Preliminary Report on the Results of the Twelfth Season of Syrian-Polish Excavations. Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean XIX, 537–554.

Bloch, M. (1971) Placing the Dead: Tombs, Ancestral Villages, and Kingship Organization in Madagascar. London/New York, Seminar Press.

Buccellati, G. and Kelly-Buccellati, M. (1988) Mozan 1. The Soundings of the First Two Seasons. Bibliotheca Mesopotamica 20. Malibu, CA, Undena.

Curvers, H. H. and Schwartz, G. M. (1990) Excavations at Tell er-Raqa’i: a small rural site of Early Urban Northern Mesopotamia. American Journal of Archaeology 94/1, 3–23.

Delougaz, P. and Lloyd, S. (1942) Pre-Sargonid Temples in the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 58. Chicago, Oriental Institute.

DeMarrais, E., Castillo, L. J. and Earle, T. (1996) Ideology, materialization and power strategies. Current Anthropology 3, 15–31.

Dohmann-Pfälzner, H. and Pfälzner, P. (1996) Untersuchungen zur Urbanisierung Nordmesopotamiens im 3. Jt. V. Chr.: Wohnquartierplanung und städtische Zentrumsgestaltung in Tall Chuera. Damaszener Mitteilungen 9, 1–13.

Dohmann-Pfälzner, H. and Pfälzner, P. (1999) Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft in Tal Mozan/Urkeš. Bericht über die Vorkampagne 1998. Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellshaft 131, 17–46.

Forest, J.-D. (1996) Mésopotamie. L’apparition de l’Etat VIIe–IIIe Millénaires. Paris, Edition Paris-Méditerranée.

Fortin, M. and Cooper, L. (1994) Canadian Excavations at Tell ‘Atij (Syria). Bulletin of the Canadian Society for Mesopotamian Studies 27, 33–50.

Lebeau, M. (2006) Les Temples de Tell Beydar et leur environnement immédiat à l’époque Early Jezirah IIIb. In P. Butterlin, M. Lebeau, J.-Y. Monchambert, J. L. Montero Fenollòs and B. Muller (eds) Les espaces Syro-Mésopotamiens. Dimension de l’expérience humaine au Proche-Orient Ancien. Volume d’hommage offert à Jean-Claude Margueron. Subartu XVII, 101–140. Turnhout, Brepols.

Lebeau, M. (2011a) 1. Introduction. In M. Lebeau with contribution by A. Bianchi, K. A. Franke, A. P. McCarthy, J.-W. Meyer, P. Pfälzner, A. Pruß, Ph. Quenet, L. Ristvet, E. Rova, W. Sallaberger, J. Thomalsky and S. Valentini (eds) Jezirah. ARCANE I, 1–17. Turnhout, Brepols.

Lebeau, M. (2011b) 13. Conclusion. In M. Lebeau with contribution by A. Bianchi, K. A. Franke, A. P. McCarthy, J.-W. Meyer, P. Pfälzner, A. Pruß, Ph. Quenet, L. Ristvet, E. Rova, W. Sallaberger, J. Thomalsky and S. Valentini (eds) Jezirah. ARCANE I, 343–380. Turnhout, Brepols.

Liebowitz, H. (1988) Terra-cotta Figurines and Model Vehicles. Malibu, CA, Undena Publications.

Mallowan, M. E. L. (1936) The Excavations at Tall Chagar Bazar, and an archaeological survey of the Habur region 1934–35. Iraq 3, 1–86.

Matthews, R. J. (2002) Seven Shrines of Subartu. In L. Al-Gailani Werr, J. Curtis, H. Martin, A. McMahon, J. Oates and J. Reade (eds) Of Pots and Plans: Papers on the Archaeology and History of Mesopotamia and Syria presented to David Oates, 186–190. London, Nabu Publications.

Matthews, R. J. (2003) A Chiefdom on the Northern Plains. Early Third-millenium Investigations: the Ninevite 5 Period. In R. Matthews (ed.) Excavations at Tell Brak, Vol. 4: Exploring an Upper Mesopotamian centre, 1994–1996, 97–191. Cambridge, McDonald Institute of Archaeological Research.

McCown, D., Haines, R. C., Biggs, R. D. and Carter, E. F. (1978) Nippur II. The North Temple and Sounding E. Oriental Institute Publications 97. Chicago, Oriental Institute.

Moortgat, A. (1967) Tell Chuera in Nordost-Syrien: Vorläufiger Berich über die fünfte Grabungskampagne 1964, Wiesbaden, Otto Harrassowitz.

Moortgat, A. and Moortgat-Correns, U. (1976) Tell Chuera in Nordost-Syrien: Vorläufiger Berich über die Siebente Grabungskampagne 1974. Berlin, Gebr. Mann.

Munchaev, R. M. and Merpert, N. I. (1994) Da Hassuna a Accad. Scavi della missione russa nella regione di Hassake, Siria di Nord-Est, 1988–1992. Mesopotamia 29, 5–48.

Munchaev, R. M., Merpert, N. I. and Amirov, S. N. (2004), Tell Hazna I. Religious and Administrative Center of IV–III millennium B.C. in North-East Syria, Moscow, Paleograph.

Orthmann, W. (1990) L’architecture religeuse de Tell Chuera. Akkadica 69, 1–18.

Palumbi, G. (2004) La più antica ‘Tomba Reale’. Dati archeologici e costruzione delle ipotesi. In M. Frangipane (ed.) Alle origini del potere. Arslantepe, la collina dei leoni, 115–119. Milano, Electa.

Parayre, D. (2003) The Ninevite 5 Sequence of Glyptic at Tell Leilan. In E. Rova and H. Weiss (eds) The Origins of North Mesopotamia Civilization: Ninivite 5 Chronology, Economy, Society. Subartu IX, 271–310. Turnhout, Brepols.

Pecorella, P. E. and Pierobon, R. (2003) La missione archeologica italiana a Tell Barri – 2002. Orient Express 3, 59–62.

Pecorella, P. E. and Pierobon, R. (2005a) Recenti scoperte a Tell Barri in Siria. Orient Express 1, 9–13.

Pecorella, P. E. and Pierobon, R. (2005b) Tell Barri/Kahat. La campagna del 2002. Firenze, Florence University Press.

Petty, A. (2004) Bronze Age Figurines from Umm el-Marra, Syria: Style and Meaning. Unpublished PhD dissertation, John Hopkins University.

Pfälzner, P. (2001) Haus und Haushalt: Wohnformen des dritten Jahrtausends vor Christus in Nordmesopotamien. Damaszner Forschungen 9. Mainz am Rhein, von Zabern.

Pfälzner, P. (2011) 5. Architecture. In M. Lebeau with contribution by A. Bianchi, K. A. Franke, A. P. McCarthy, J.-W. Meyer, P. Pfälzner, A. Pruß, Ph. Quenet, L. Ristvet, E. Rova, W. Sallaberger, J. Thomalsky and S. Valentini (eds) Jezirah. ARCANE I, 137–200. Turnhout, Brepols.

Pruß, A. (2011) 7. Figurines and Model Vehicles. In M. Lebeau with contribution by A. Bianchi, K. A. Franke, A. P. McCarthy, J.-W. Meyer, P. Pfälzner, A. Pruß, Ph. Quenet, L. Ristvet, E. Rova, W. Sallaberger, J. Thomalsky and S. Valentini (eds) Jezirah. ARCANE I, 239–254. Turnhout, Brepols.

Rova, E. (2011) 3. Ceramic. In M. Lebeau with contribution by A. Bianchi, K. A. Franke, A. P. McCarthy, J.-W. Meyer, P. Pfälzner, A. Pruß, Ph. Quenet, L. Ristvet, E. Rova, W. Sallaberger, J. Thomalsky and S. Valentini (eds) Jezirah. ARCANE I, 49–128. Turnhout, Brepols.

Schwartz, G. M. (1994a) Before Ebla: Models of Pre-State Political Organization in Syria and Northern Mesopotamia. In G. Stein and M. Rothman (eds) Chiefdom and Early States in the Near East: The Organizational Dynamics of Complexity. Monographs in World Archaeology 18, 153–174. Madison, Prehistory Press.

Schwartz, G. M. (1994b) Rural Economic Specialization and Early Urbanization in the Khabur Valley, Syria. In G. M. Schwartz and S. E. Falconer (eds) Archaeological Views from the Countryside: village communities in early complex societies, 19–36. Washington, Smithsonian Institution Press.

Schwartz, G. M. (2000) Perspectives on Rural Ideologies: the Tell Raqa’i ‘Temple’. In O. Rouault and M. Wäfler (eds) La Djéziré et l’Euphrate Syriens de la Protohistoire à la Fin du Iière millénaire av. J.–C. Subartu VII, 163–182. Turnhout, Brepols.

Schwartz, G. M. (2006) From Collapse to Regeneration. In G. M. Schwartz and J. J. Nichols (eds) After Collapse. The Regeneration of Complex Societies, 3–17. Tucson, The University of Arizona Press.

Schwartz, G. M. and Falconer S. E. (1994) Rural Approach to Social Complexity. In G. M. Schwartz and S. E. Falconer (eds) Archaeological Views from the Countryside: village communities in early complex societies, 1–9. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Smogorzewska, A. (2004) Andirons and their role in Early Trancaucasian Culture. Anatolica 30, 151–177.

Smogorzewska, A. (2009) Burnished Ware: Ninevite 5 Period Pottery from Tell Arbid. Orient Express 1, 35–37.

Sołtysiak, A. (2008) Short Fieldwork Report: Tell Barri (Syria), seasons 1980–2006. Bioarchaeology of the Near East 2, 67–71.

Suleiman, A. and Taraqji, A. F. (1995) Tell Kashkashouk III. In M. al-Maqdissi, Chronique des activités archéologique en Syria 2. Syria 72, 159–266.

Takaoğlu, T. (2000) Hearth structures in the religious pattern of Early Bronze Age northeast Anatolia. Anatolian Studies 50, 11–16.

Valentini, S. (2006–2007) Communal Places of Worship in Jezirah during the EJ II–IIIa period (2750–2550 BC). ANODOS 6–7. Special Issue (Proceedings of the International Symposium, Cult and Sanctuary through the Ages. From the Bronze Age to the Late Antiquity. Častá-Papernička, Slovakia 16–19 November 2007), 475–486.

Valentini, S. (2008a) Ritual Objects in the “rural shrines” at Tell Barri, in the Khabur region, during the Ninevite 5 period. In J. M. Córdoba, M. Molist, M. Carmen Pérez, I. Rubio, S. Martìnez (eds) Proceedings of the 5th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East (Madrid, 3–8 April 2006), 345–357. Madrid, Centro Superior de Estudìos sobre el Oriente Próximo y Egipto.

Valentini, S. (2008b) The Jezirah Burnished Ware. Antiguo Oriente 6, 25–38.

Valentini, S. (2009) Burial practices in the first half of the IIIrd Millennium in the Khabur Region. In A. Foron (ed.) Troisiemes Rencontres Doctorales Orient Express. Actes du Colloque tenu a Lyon les 10 et 11 Fevrier 2006 a la Maison de l’Orient et de la Mediterranee, 63–78. Paris, Orient-Express-Archéologie Oriental.

Valentini, S. (2011) 9. Burials and funerary practices. In M. Lebeau with contribution by A. Bianchi, K. A. Franke, A. P. McCarthy, J.-W. Meyer, P. Pfälzner, A. Pruß, Ph. Quenet, L. Ristvet, E. Rova, W. Sallaberger, J. Thomalsky and S. Valentini (eds) Jezirah. ARCANE I, 261–275. Turnhout, Brepols.

Weiss, H. (1990a) ‘Civilizing’ the Habur Plains: Mid-Third Millennium State Formation at Tell Leilan. In M. van Loon and P. Matthiae (eds) Resurrecting the Past: a joint tribute to Adnan Bounni, 387–407. Istanbul, Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut.

Weiss, H. (1990b) Tell Leilan 1989: New Data for Mid-Third Millennium Urbanization and State Formation. Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellshaft 122, 193–218.

Wilkinson, T. J. and Tucker, D. J. (1995) Settlement Development in the North Jazira, Iraq. Iraq Archaeological Reports 3. London, British School of Archaeology in Iraq.