A temple lifecycle: rituals of construction, restoration, and destruction of some ED Mesopotamian and Syrian sacred buildings

Sacred buildings and Temples are par excellence places of ritual actions and, thus, contexts in which it is easier to find traces of religious activities. Nevertheless in this occasion I will try to shed light on those rituals related to the life of the sacred building itself, to its construction, restoration and destruction, analysing different examples from Mesopotamia and Syria dated to the 3rd millennium BC. The rituals including communal sharing of food and drinks will be highlighted thanks to their archaeological visibility. Among the examples, a particular attention will be given to the case of the Eblaic Temple of the Rock and to the ritual following its destruction.1

The edification of the Temple

The construction of a Temple was an extremely important act: it was the way for the king to provide and guarantee a house for its god, allowing him to be present inside his community.2 This action, repeated during centuries by every king, was worth of being remembered not only in the year’s names or in the official inscriptions, but also of being tied indissolubly to the same structure of the temple, inscribing the king’s name, incised on an adequate support, inside foundations deposits realised in key points of the building. The most typical kind of deposit for the ED III to the UR III Period consisted, in fact, in a foundation nail, often inscribed and connected to stone pierced tables.3

Rituals concerning a sacred building should be traced since the first steps of its construction: the determination of its position4 through mantic arts or on the basis of natural characteristic or astronomic observations, should have involved some ritualised acts. A particular attention for the place’s choice and preparation is attested at Uruk and Khafaja. In the Mosaic Temple of Warka (Uruk III c), trough-like trenches were dug parallel to the partitions walls of some rooms. Alongside these trenches shards of four big pots were discovered, three of them containing also traces of food, fish-bones, birds and mammals.5 Instead, for the foundation of the Khafaja Oval Temple, the soil, consisting in earlier debris and thus considered impure, was dug and removed for being substituted by pure sand, with no traces of potsherds or organic material.6

The beginning of edification and not only its end, were worth of being celebrated. It is plausible that a banquet was held during the ceremony of the first brick laying, as shown for the 4th and 3rd Millennium BC by some archaeological proofs. The first evidence of this practice is testified by a deposit in the proto-literate phase (Strata X) of Tepe Gawra: inside an external bench in the western corner of Room 1003 a Wide Flower pot and two other clay cups have been discovered.7

At Ur, instead, near the southern corner of the Neo-Babylonian temenos, Woolley unearthed some fragments of a wall dated to the ED. In three different points, under this structure and inside its foundation level, some pits have been discovered with vases filled with food remains.8 Also in the Barbar Temple, discovered in Bahrein, different objects, among which various beakers, were unearthed walled inside the terrace at the base of the ED III Temple9.

A detailed account of the ceremonies related to the beginning of the Temple Building can be found in the inscription of Gudea’s Cylinders A and B.10 The texts describe the complex ritual for the construction of the House of the god Ningirsu, a ritual performed during the last centuries of the 3rd millennium but conceivably founded on earlier lagashite traditions. It must be highlighted here the importance given by Gudea and the Lagash citizens to the purification of the city and of the place chosen for the construction of the temple. The purification was obtained through the use of fire and incense. Moreover, a particular ritual is described for the creation of the first brick: the king poured clear water into the brick mould and prepared the earth mixed with honey, ghee, precious oil, balsam and essences, then he put a basket near the mould.11

It is probable, as said, that a similar ritual took place also in the Lagash of the second half of the 3rd millennium BC. In fact, in the famous plaques portraying Urnanše with his family,12 the king is represented in the act of carrying the brick basket and while celebrating the end of the works with a cup in his hand.13

It is here important to quote some ED seals often interpreted as representing the construction of a sacred building, similar to the Ziqqurat, associated to the consumption of a banquet by a human or sometimes by a divine character.14 Nevertheless, the dimensions of the objects build up by the men, together with the usual presence of astral symbols such as the so-called dieu-bateau, seems to point instead towards an identification of the structure with an altar for offerings. The seals, thus, should represent not a ritual connected to the Ziqqurat edification but a celebration linked to a specific astral and calendric event.

Restoration, destruction and reconstruction of the Temple

Also the construction or reconstruction of specific features or parts of the temples was charged of a particular value, such as the realisation of altars or other structural elements, as perhaps testified by the Šara Temple at Tell Agrab, in the phase of the so-called Earlier Building. Here, inside the altar in M 14:15 and inside the closure of an earlier door, a deposit with beads, broken amulets and various cups, have been discovered: some of the vessels had a black substance inside, described by excavators as similar to charcoal but probably to be interpreted as food remains.15

In general, the reconstruction of a sacred building was an act of extreme importance: in the Mesopotamian history every king had to re-establish the original condition of the sanctuary of his god, according to the authentic project conceived by his deity.

During the reconstruction or restoration of a sacred building a particular attention was given to the preservation of the older furnishing that were kept inside pits, like for example the famous hoard of the Abu Temple in which the worshippers’ statues were buried with extreme attention, thus preserving intact also the inlayed eyes.16

As seen, the place chosen for the construction of a Temple should be suitable to host the house of the god and, thus, it should be purified through passage rituals ratifying the new status of the area. This condition of purity had to be maintained during all the life stages of the building. It should be imagined that, if a sacred building underwent to destruction due to a natural or human event, probably every restoration or rebuilding should be preceded by new rituals aiming to re-establish the original integrity of the sacred place.

The Eblaic Temple of the Rock

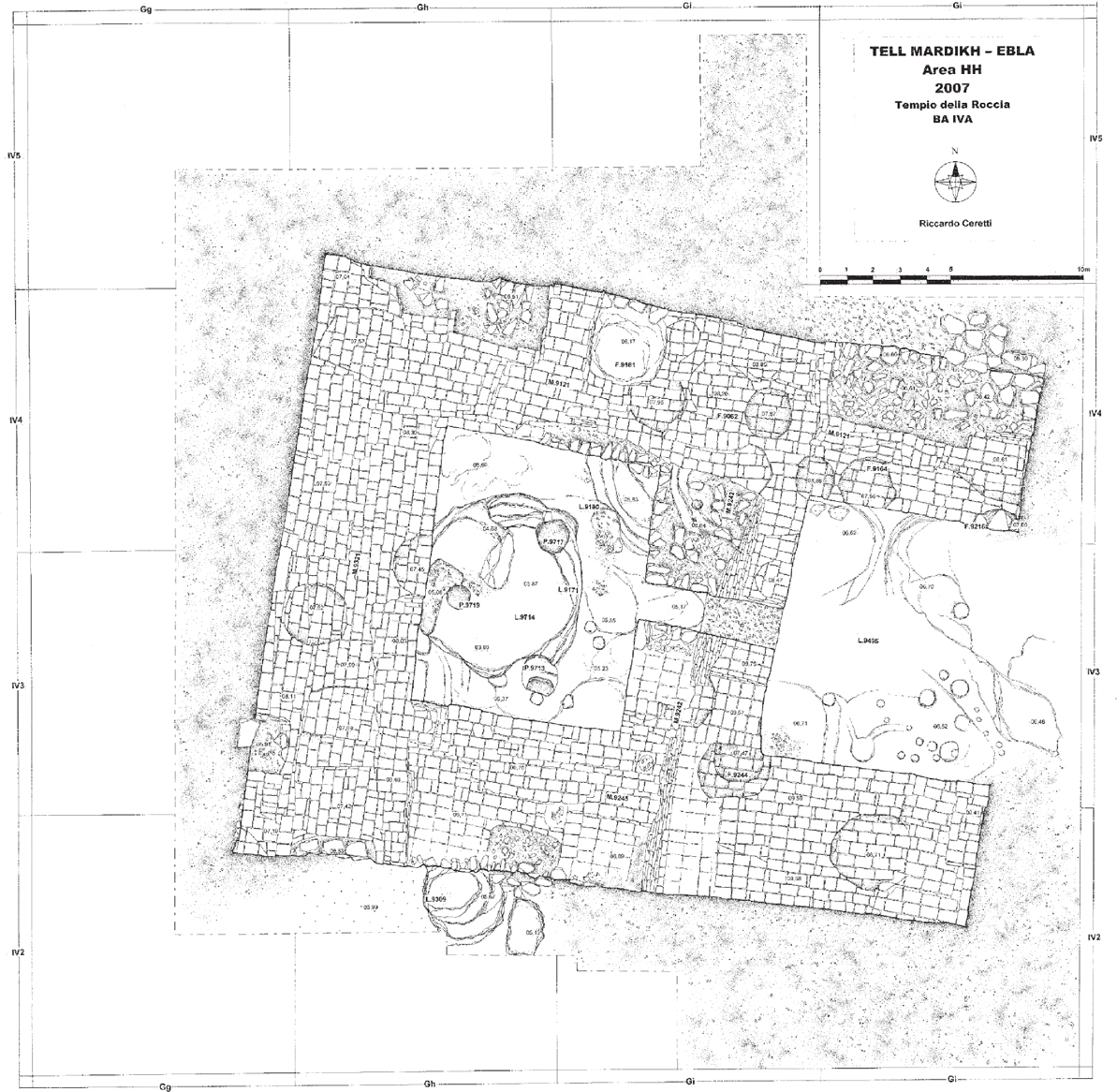

A clear proof of this kind of practice is testified at Ebla in Syria, in the so-called Temple of the Rock. The sacred building was discovered by Paolo Matthiae in 2004 thanks to a geo-magnetic prospection, indicating the presence of limestone pebbles in the south-eastern part of the Lower Town.17 The limestone pebbles were, in fact, used to seal the cella of the big Temple after the destruction due to the military activities of Sargon of Akkad.18 The cella was completely excavated during the 2007 campaign. The pavement of the temple’s main room was constituted by the rock surface. In the central part of the cella, towards the west limit of the room, there was an elliptical cavity (L.9714) cut by three pits: P.9719, P. 9717, P.9713.

Fig. 12.1: The Temple of the Rock from East (© MAIS).

Fig. 12.2: The Temple of the Rock (© MAIS).

Of the three pits, P.9713, was sealed by stones of medium and big-size, while the other two pits were not closed, though the static capacity of the rock was quite precarious. P.9713, the only sealed pit, was clearly in connection with a cavity, running under the perimeter wall of the temple. Only P.9717 and P.9719 have been excavated due to security reasons.19 The three pits in the middle of the cella were, according to P. Matthiae, water sources connected to the cult of the god worshipped inside the temple, in his opinion, the enigmatic KURA, well-know from the Ritual of the Royalty, whose sacred building was located near the KURA’s Gate, the south-eastern gate of the city. The god KURA was a divinity of the El kind, associated thus to the water of the Abzu. On one hand the presence inside the cella of the Temple of the Rock of three cavities probably connected to water canals running under the Tell surface, on the other hand the proximity of the Temple to the South eastern gate of the city undoubtedly result in an identification of the Temple of the Rock with the Holy House of Kura.

Chronological information about the Sacred building and its destruction come from the door between the vestibule and the cella: some pottery fragments of the Early Bronze IVA were discovered here together with the only burned remains of the destruction. The date, instead, of the cleaning of the cella and, thus, of its sealing is clarified by the pottery discovered inside the pits: they were filled, in fact, by numerous vases of medium dimensions of the well know Early Bronze IVB horizon. It is now clear that, before the reconstruction of the sacred building in the Early Bronze IVB, the temple and in particular its cella, the house of the god, was cleaned and sealed with fourteen courses of bricks and then with a thick layer of limestone pebbles.20

The cleaning of the cella was a ritual act of extreme importance, whose traces were preserved inside the Favissae dug into the rock in the middle of the room. The findings of the two excavated pits of the cella testify a complex ritual connected to the purification of the destroyed temple and to the sealing of the burned structure before the building of the new Temples HH4 and HH5.21 I will analyse the stratigraphy of the two pits trying to clarify the complex purification ritual, starting with the description of the Favissa P.9719.

Favissa P.9719

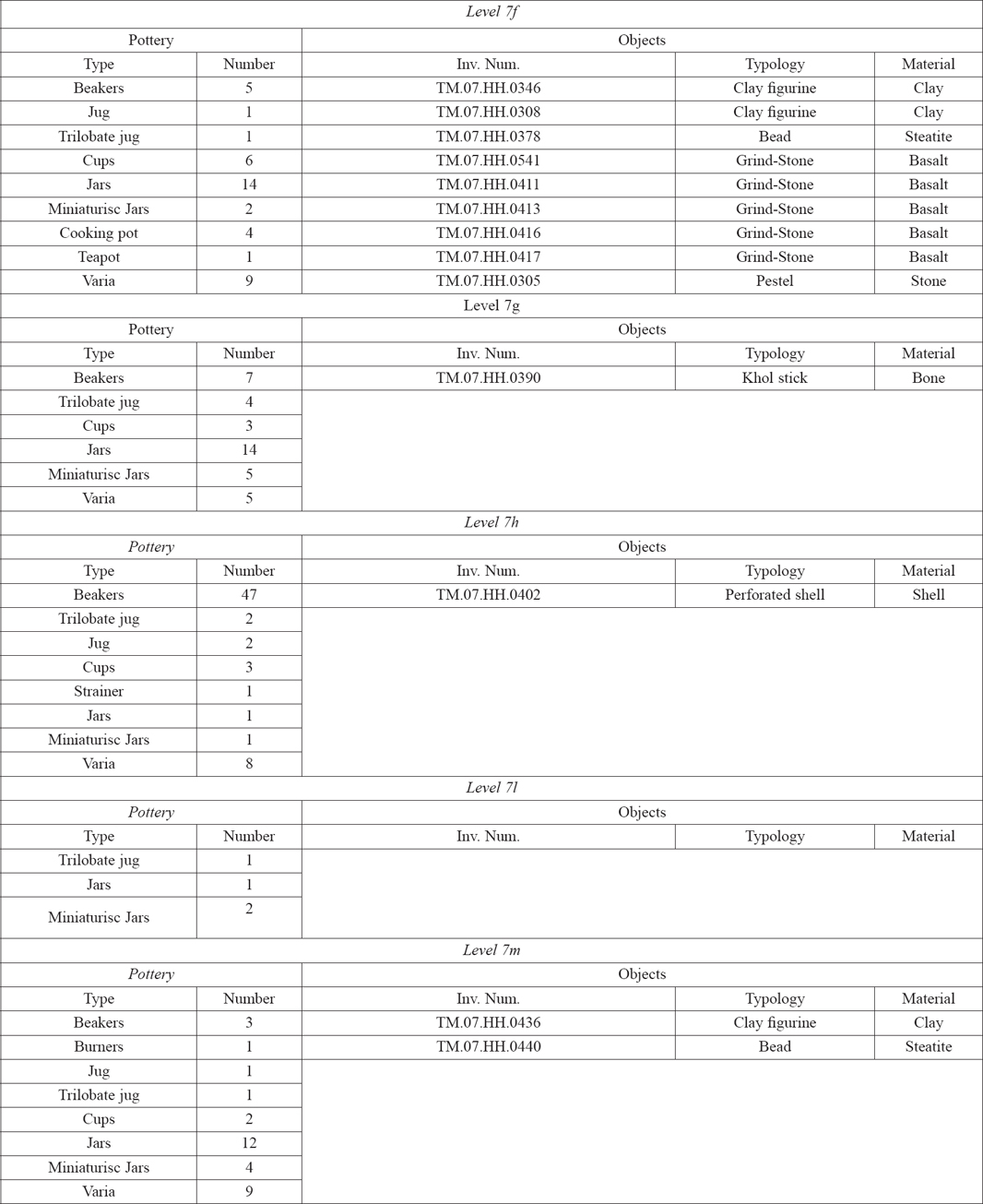

The first filling level (level f) of P.9719 consisted of compact reddish-brown clay soil with limestone inclusions of medium dimensions, stones of large and medium size, fragments of burned mud-bricks and pottery sherds. The pottery found inside the level consisted of 11 drinking vessels, 2 jugs, 14 normal and 2 miniaturistic jars and 1 teapot. From the study of the pottery and the other findings, it is noteworthy that the presence of sherds of at least four cooking pots, basalt grindstones, a pestel and fragment of a human and of animal figurines (Table 12.1).

The second level (level 7g) consisted of a grey-brown clay-sandy soil, almost compact, with stones of small and medium size. Within this context were discovered 10 drinking vessels, 4 trilobate jugs, 14 jars, and 5 miniaturistic jars.

The third level (level 7h), a clay and grey compact soil, was very rich in pottery sherds. Among these were: 2 trilobate and 2 normal jugs, 1 strainer, 1 miniaturistic and 1 normal jar. Tthe presence of 47 beakers and 3 cups within this level should be highlighted.

The fourth level (level 7l), a light brown, quite friable soil, with rock flakes of small and medium dimensions, contained fewer pottery sherds than the other levels: only 1 Trilobate jug, 1 normal and 2 minaturistic jars.

The last level (level 7m) of the filling was a grey compact and grained soil. Five drinking vessels, 1 trilobate and 1 normal jug, 12 jars, 4 miniaturistic jars and 1 incense burner were discovered scattered in the soil. Moreover we found a steatite bead and a broken animal figurine.

Favissa P.9717

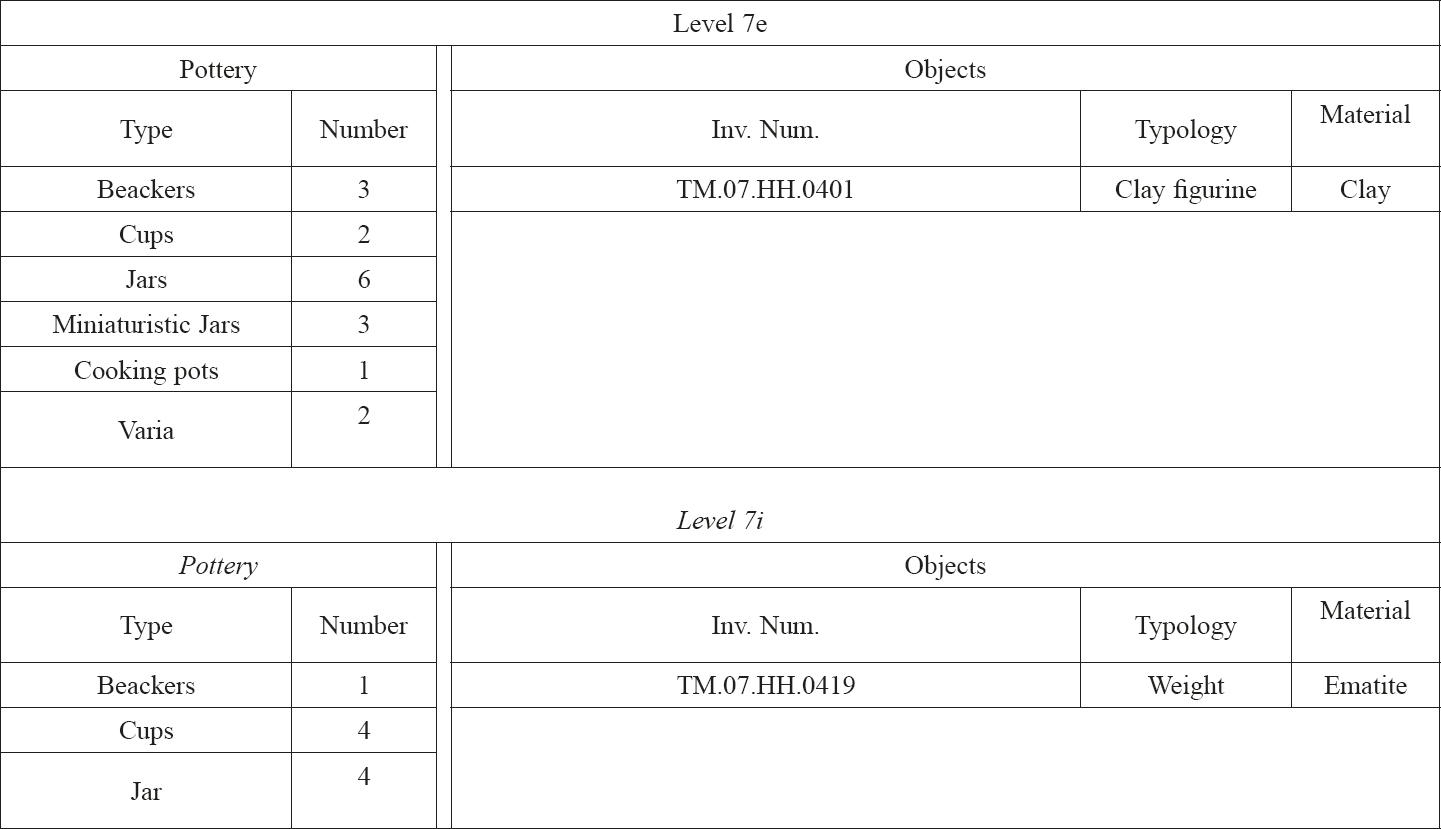

The first filling level (Level 7e) consisted of a light brown sandy and friable soil with pottery fragments and animal bones. Some stones were placed near the walls of the pit next to the enlargement of the rock cavity (Table 12.2).

The second and last level (Level 7i) was filled by a clay, grey soil. In the lower part of the pit a sort of circle of stone was set down.

Analysis of the Two Favissae

From the comparison of the sections of the two pits it is possible to highlight some details of the ritual celebrated.

The first levels of the two pits contained what we can define the refuse, the garbage of the ritual. P.9719 was sealed with the material used for the preparation of the banquet: the grinding-stones and the pestel, that we can suppose were used to crush some foods during the preparation, and some cooking pots, the only shards of this kind found inside both pits. The soil in which the pottery and the objects were discarded was not pure but mixed to bricks and stone fragments.

The same impure soil was used to seal P.9717, mixed with bones, probably the remains of the banquet.22

The grey soil immediately under the closure level contained the remains of the pottery used in the banquet: in level 7h of P.9719 a huge amount of drinking vessels have been discovered together with a strainer, probably used to filter the liquids served as beverage.

In P.9719 another brown soil level was used to distinguish the banquet equipment from the rest of what could be interpreted as the remains of the purification ritual, realised with the use of jugs for the pouring of liquids and with an incense burner. As we have already seen, the purification of a place through incense and liquids is attested also in later periods, as testified by Gudea’s inscriptions.

Unfortunately, in no case it is possible to specify the function of the miniaturistic vessels discovered in the levels. In general the function of small-scale vessels as containers for particular liquids or substances, or their use for special purposes, can be understood only on the basis of the excavation context.23 In the case of the two Favissae, it could be possible to suppose that the miniaturistic vessels discovered in levels 7g and 7h of P.9719 were connected to the symposium celebration, thus containing perhaps substances used in small quantities by the banqueters with or without any specific religious value. On the other side the small jars discovered in level 7m should contain liquids utilised for the temple purification. The small scale vessels in P.9717 could have been used during the food preparation.

Table 12.1

Table 12.2

Fig. 12.3: L.9714 and the three Favissae in the Cella of the Temple of the Rock (© MAIS).

The presence in the first and last levels of P.9719 of two steatite beads and of broken human and animal figurines could hide a ritual meaning we are still not able to understand. The presence in the first and last levels of deposition of two identical beads is strange but we cannot exclude the casualness of their position in the filling. It could be also possible to hypothesise a ritual destruction of the clay figurines as a sort of execration ritual or of symbolic sacrifice, but we do not have any concrete proof of their intentional breaking, neither of the figurines present the same kind of fractures.24 Nevertheless, from the study of the pottery we could hypothesise a ritual breaking of the vessels used in the celebration: few of them are in fact preserved entirely, but it should be considered also that the same deposition inside the pits could have caused the breakage.

A last hint on the ritual procedure could be deduced by the presence of five drinking vessels, thrown separately in P.9717. This separated deposition could hide a particular use of these vessels or could indicate that they were used by special guests or actors of the ritual, perhaps the same involved in the libations and the purification ceremonies.

Conclusions

The ritual attested in the Temple of the Rock consisted in two separated but yet strongly connected moments (Fig. 12.4): first, the purification as a moment of passage from a negative situation (the destruction of the holy building and the consequent loss of purity of the sacred area) to the reestablishment of the pureness of the god’s house; secondly, the banquet as a communal moment in which the consumption of food and drinks symbolised the re-unification of the community struck by such a dangerous calamity (a function certainly comparable to that hold by the funerary banquet following the loss of a member of the community). Thus, the ceremony whose traces were preserved inside the favissae could not be defined at all as a “termination” ritual: surely it ratified the final abandonment of the Early Bronze Age sacred building but, in the meanwhile, it removed every trace of impureness of the area, allowing the construction of a new and holy house for the god and the renovation of the normal temple activities.

The analysis of the stages of the Temple’s life here attempted has demonstrated once again that the Temple was considered as a living part of the city and the community, a particular member, representing the presence of the god in the city, a member that was celebrated in every passage of its life, from its birth to its renovation and sometimes to its death and reconstruction.

Fig. 12.4: Schematic stratigraphic sequence of P.9717 and P. 9719.

1 I would like to thank Prof. Paolo Matthiae for the permission of analysing in detail the findings of the two Eblaic Favissae, and Davide Nadali, who excavated the pits with extreme competence.

2 Matthiae 1994, 37. On the Temple foundation and Building rituals see Averbeck 2010.

3 Ellis 1968, 76–77; Rashid 1983; see for the Egyptian evidence Weinstein 1973.

4 Ellis 1968, 8.

5 Van Buren 1952, 78–80, pl. xxviii, 1; Lenzen 1959, 11–12.

6 See Delougaz 1940, 11–17 fig. 11; Ellis 1968, 10.

7 Tobler 1950, 11–12, pls iii–xiii; Ellis 1968, 126–127; Rothman 2002, 116 fig. 5.44.

8 Woolley 1962.

9 Glob 1955, fig. 5; Weidner 1957–58; Ellis 1968, 128.

10 On this topic see: Suter 2000; Averbeck 2010.

11 On Gudea and the building of his Temple see Suter 2000.

12 Romano in press.

13 In Urn.49 (IV 1–4) is the personal god of the king to made the construction work.

14 See for example Amiet 1980, pl. 108 n. 1442; pl. 109 nn. 1444, 1450.

15 Delougaz and Lloyd 1942, 257. On the analysis of the deposit see Ellis 1968, 136 and Tunça 1984, 187.

16 Delougaz and Lloyd 1942, 188 fig. 149. On hoards and in general the ritual burial of objects in the Ancient Near East see the introduction of the contribution of Garfinkel 1994.

17 Matthiae 2006, 458–460, figs 11–13.

18 Matthiae 2009c, 120; 2010, 60–63.

19 Matthiae 2009b, 688.

20 Matthiae 2009a, 754–757; 2009b, 688–691.

21 Matthiae 2009b, 688.

22 Analysis of cut traces on the bones are still in progress.

23 The term “miniature” does not imply any qualitative valuation of an object, indicating only the realisation in a reduced scale. Nevertheless in the literature the term “miniature” is used generally referring to vessel with a particular religious or votive use and value, so it should be possible to prefer locutions such as “of small dimension” to refers to those small scale object realised for a normal use (Zamboni 2009, 11, 22–23). The function of miniature/small dimension vessel should be interpreted on the base of the context (Osborn 2004, 7): they could serve as container for votive offering (Allen 2006, 23) or as part of a temple or burial equipment, they should contain perfumes or precious substances used during rituals or during the daily life, or again they should be interpreted as sort of toys for children (Paz and Shoval 2012, 10; on the identification and interpretation of toys in archaeological context see Baxter 2005, 39–50). Sometimes the presence of large scale exemplars of a miniature vessel could help in the identification of its use (Kohring 2011, 38; Notroff 2011).

24 Moreover, according to L. Peyronel (pers. comm.), the clay figurines discovered inside the favissa seems not to belong to an archaic phase of the EB IVA and show traces of incrustation that are instead not evident in the pottery fragments.

Bibliography

Allen, S. (2006) Miniature and Model Vessels in Ancient Egypt. In M. Bárta (ed.) The Old Kingdom Art and Archaeology Proceedings of the Conference Held in Prague, May 31–June 4, 2004, 19–24. Prague, Miroslav Bárta, editor.

Amiet, P. (1980) La glyptique mésopotamienne archaïque, Paris, Éditions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

Averbeck, R. E. (2010) Temple Building Among the Sumerians and Akkadians (Third Millennium). In M. J. Boda and J. Novotny (eds) From the Foundations to the Crenellations. Essays on Temple Building in the Ancient Near East and Hebrew Bible, 3–34, Alter Orient und Altes Testament 366. Münster, Ugarit-Verlag.

Baxter, J. E. (2005) The Archaeology of Childhood. Children, Gender, and Material Culture, Gender and Archaeology Series 10. New York, AltaMira Press.

Delougaz, P. (1940) The Temple Oval at Khafajah, OIP 53. Chicago, The University of Chicago Press.

Delougaz, P. and Lloyd, S. (1942) Pre-Sargonid Temple in the Diyala Region, OIP 58. Chicago, The University of Chicago Press.

Ellis, R. S. (1968) Foundation Deposits in Ancient Mesopotamia. New Haven and London, Yale University Press.

Garfinkel, Y. (1994) Ritual Burial of Cultic Objects: The Earliest Evidence. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 4:2, 159–188.

Glob, P. V. (1955) The Danish Archaeological Bahrein Expedition’s Second Campaign. Kuml 1955, 109–191.

Kohring, S. (2011) Bodily Skill and the Aesthetics of Miniaturization, PALLAS 88, 31–50.

Lenzen, H. (1959) XV. Vorläufiger Bericht über die von dem Deutschen Archäologischen Institut und der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft aus Mitteln der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft unternommen Ausgrabungen in Uruk-Warka. Winter 1956/57, Abhandlungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 4. Berlin, Verlag der Notgemeinschaft.

Matthiae, P. (1994) Il sovrano e l’opera. Arte e potere nella Mesopotamia Antica. Roma-Bari, Laterza.

Matthiae, P. (2006) Un grand temple de l’époque des Archives dans l’Ebla protosyrienne: Fouilles à Tell Mardikh 2004–2005. CRAIBL 2006, 447–493.

Matthiae, P. (2009a) Temples et reines de l’Ébla protosyrienne: résultats des fouilles à tell mardikh en 2007 et 2008. CRAIBL 2009, 747–792.

Matthiae, P. (2009b) Il Tempio della Roccia ad Ebla: la residenza mitica del dio KURA e la fondazione della città protosiriana, Scienze dell’Antichità 15, 677–730.

Matthiae, P. (2009c) Temple and Queens at Ebla. Recent Discoveries in a Syrian Metropolis between Mesopotamia, Egypt and Levant. In Interconnections in the Eastern Mediterranean. Lebanon in the Bronze and Iron Ages. Proceedings of the International Symposium Beyrut 2008, BAAL Hors-Séries VI, 117–139. Beirut, Ministry of Culture of Lebanon.

Matthiae, P. (2010) Recent Excavations at Ebla, 2006–2007. In P. Matthiae, F. Pinnock, L. Nigro, N. Marchetti and L. Romano (eds) Proceedings of the 6th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East May, 5th–10th 2008, “Sapienza” – Università di Roma, Volume 2, Excavations, Surveys and Restorations: Reports on Recent Field Archaeology in the Near East, 3–26. Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz.

Notroff, J. (2011) Vom Sinn der kleinen Dinge. Überlegungen zur Ansprache und Deutung von Miniaturgefäßen am Beispiel der Funde von Tall Ḥujayrāt al-Ghuzlān, Jordanien. ZOrA 4, 246–260.

Osborne, R. (2004) Hoards, Votives, Offerings: The Archaeology of the Object. World Archaeology 36:1, 1–10.

Paz, Y. and Shoval, S. (2012) Miniature Votive Bowls as the Symbolic Defense of Leviah, an Early Bronze Age Fortified Town in the Southern Levant. Time and Mind: The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness and Culture 5:1, 7–18.

Rashid, S. A. (1983) Grundungsfiguren im Iraq. Munich, Prähistorische Bronzefunde 1/2.

Romano, L. (2014) Urnanshe’s Family and the Evolution of its Inside Relationships as Shown by Images. Proceedings of the 55th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale. “Family in the Ancient Near East: Realities, Symbolisms, and Images”, 183–192. Winona Lake, Indiana, Eisenbrauns.

Rothman, M. S. (2002) Tepe Gawra: The Evolution of a Small, Prehistoric Center in Northern Iraq, University Museum Monograph 112. Philadelphia, Penn Press.

Suter, C. (2000) Gudea’s Temple Building: The Representation of an Early Mesopotamian Ruler in Text and Image, CM 17. Groningen, Brill.

Tobler, A. J. (1950) Excavations at Tepe Gawra. Philadelphia, Penn press.

Tunça, Ö. (1984) L’architecture Religieuse Protodynatique en Mesopotamie, Akkadica Supplementum II. Leuven, Peeters.

Van Buren, E. D. (1952) Places of Sacrifice (‘Opferstätten’). Iraq 14, 76–92.

Weidner, E. (1957–58) Ausgrabungen und Forshungreisen: Bahrein. AfO 18, 157–158.

Weinstein, J. M. (1973) Foundation Deposits in Ancient Egypt. Ph.D dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Woolley, L. (1962) Ur Excavations, Volume IX: The Neo-Babylonian and Persian Periods. London, British Museum.

Zamboni, L. (2009) Ritualità o utilizzo? Riflessioni sul vasellame “miniaturistico” in Etruria padana: Pagani E Cristiani. Forme ed attestazioni di religiosità del mondo antico in Emilia VIII, 9–46. Castelfranco, All’Insegna del Giglio.