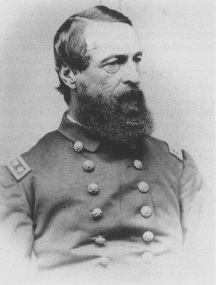

David Dixon Porter

David Dixon Porter

U.S. NAVY

DAVID DIXON PORTER LIVED IN THE SHADOW OF HIS FAMOUS FATHER, Commodore David Porter, an adventurous, independent officer whose annihilation of the British whaling fleet in the War of 1812 made him both a popular national hero and the most successful member of an old naval family. Commodore Porter, who had gone to sea with his own father at an early age, wanted sons to carry on the family tradition. His foster son, David G. Farragut, won the Navy’s first admiralcy. Of the commodore’s six natural sons, David Dixon—neither the eldest nor his father’s favorite—became the second admiral of the Navy, both because of his father and despite him. From the first, he had to struggle to be noticed.

David Dixon, born while his father sailed the Pacific in the Essex, retained an idealized memory of his childhood. Commodore Porter was his greatest hero. Stimulated by his father’s war stories and constantly aware of his heritage, Porter lived secure in the childlike belief that his father, a member of the Board of Navy Commissioners, literally ran the Navy. The commodore returned to sea duty in the West Indies in 1823. On one cruise, in 1824, he took along the entire family. David Dixon’s first voyage lasted only a few months. He was away at school when, at Fajardo, Puerto Rico, Commodore Porter overstepped his authority by demanding an apology for disrespect to an American warship, was court-martialed, and received a six-month suspension. Incensed, David Porter resigned his commission and entered the service of the Mexican navy. He took with him David Dixon, age twelve; his favorite son, Thomas, age ten; and a nephew.

David Dixon watched his father sternly mold the Mexican seamen into a fighting unit and saw more action in a few months with the Mexican navy than he would during the next thirty-five years. On board his cousin David H. Porter’s ship the Guerrero, in close combat with the Spanish frigate Lealtad, David Dixon received his first war wound, and he was captured and imprisoned in Havana Harbor. When paroled, he returned to the United States, where his maternal grandfather, Congressman William Anderson, wrangled him a midshipman’s appointment in the U.S. Navy. His brother Thomas died in Mexico, and his other brothers distanced themselves from their father. Only David Dixon pleased his father, who, by the time of his death in 1843, found life and family disappointing. David Dixon Porter fought for naval distinction to earn his father’s love and to restore his father’s tarnished image.1

Porter’s midshipman career was fairly routine. His father had taught him tradition, discipline, and seamanship; the Navy, technical skills and leadership. Porter became an expert channel surveyor and pilot in the Coast Survey and the Hydrography Department. He learned quickly and became known as a man who thought on his feet and who could be trusted with special operations. Detached to State Department service, he secretly surveyed Santo Domingo to determine its suitability as a naval base.

Porter participated in several major naval engagements of the Mexican War. His operational experiences, although totaling only a few hours of battle, demonstrated his inventiveness and courage. He planned and helped to execute the naval bombardment on the defenses of Vera Cruz and, leading a sailors’ charge on the fort at Tabasco, captured the works and earned command of his first steamship, the Spitfire.

After the war, Porter sought to captain a modern steamer, but the peacetime Navy could afford only sail craft, and he was reassigned to the Coast Survey. Like many other young officers, Porter, anticipating a lifetime as lieutenant with little chance of advancement in rank or duty, chose a safe, attractive alternative: he obtained leave and captained mail vessels between New York and San Francisco, thus gaining valuable experience in commanding large ocean steamships. On board the Panama, Georgia, and Crescent City, Porter tried to instill naval discipline into civilian crews. Although he was a formalist like his father, Porter’s disciplinary methods were less punitive than paternal. He also gained popular notice by nearly re-creating his father’s Fajardo incident when, at Havana in 1852, he refused to accept the closure of the port to his mail vessel and almost provoked war between the United States and Spain.

Porter soon gained a reputation for speed, even at the expense of his mail route. Setting new world records in the remarkable Golden Age, he cut the voyage from England to Australia by a third; the Melbourne-Sydney run in half. Porter’s Australian adventures netted him something more valuable than money and experience: fame made him a national figure and raised him from the ranks of “one of the Porters.” He became known in his own right for his energy, perseverance, and clever direction of “unusual enterprises.”2

Porter returned to naval duty in the spring of 1855 to command the store-ship Supply, ferrying camels from the Mediterranean to Texas for the War Department, and later served as executive officer of the Portsmouth (New Hampshire) Navy Yard. After three years’ administration of inert peacetime shipbuilding, he negotiated for a return to civilian duty. At the age of forty-seven, having spent twenty years as a lieutenant, Porter was fully aware that his childhood heroes had made their careers at nearly half his age. As he debated between captaining another mail vessel or a Coast Survey schooner, Abraham Lincoln won the presidency, and the Southern states began to secede. Members of the Navy Department eyed each other with distrust as more Southern ports fell into Confederate hands and officers resigned to go south.

Porter seized the moment. Along with his neighbor, Army Captain Montgomery C. Meigs, Porter formulated plans to reinforce Fort Pickens and recapture Pensacola, Florida. Secretary of State William H. Seward took their plans to the President. Lincoln agreed that Pickens, like Fort Sumter, should be saved if at all possible, and he allowed Porter and Meigs to write their own orders and attempt the mission without the knowledge of their superiors. In addition, Porter wrote a cryptic order, over Lincoln’s signature, attempting to restructure civilian control of naval policy by effectively reorganizing personnel detailing within the Navy Department.3

Porter charged off to New York and quickly fitted out his ship, the Powhatan. The President had second thoughts and had Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles order Porter to give up the Powhatan to her assigned duty with Gustavus V. Fox’s expedition to relieve Sumter, but neither Porter nor Meigs was willing to let his chance for action and advancement go by. Proclaiming Welles’s telegram “bogus,” they stalled by wiring Seward to confirm the order while they went to sea. By the time Seward’s terse reply reached Porter, he had left the harbor and would not put back. Rationalizing that presidential orders outweighed cabinet ones, he politely refused to comply. With his experience of short wars and stalled promotions, this chance, he feared, might be his only one.4

Porter steamed toward Pensacola in an unsound ship with an untrained crew. Organizing en route, he drilled the men at the guns and disguised the ship as a mail steamer. Arriving near Pickens on 17 April 1861, Porter prepared to steam straight in and retake Pensacola by surprise, but Meigs stopped him. The Army was unwilling to provoke a battle before ensuring its own invulnerability, and the commanders wavered at disobeying presidential orders calling for strictly defensive operations. Frustrated, Porter raged up and down the harbor, surveyed the bay for shelling positions, and planned a night attack at the Army’s convenience. It never happened. The Union Army retained Fort Pickens and gave up any attempt to retake Pensacola, a decision that Porter later called “the great disappointment of my life.”5

The Powhatan incident had several repercussions. Lincoln learned to confide in his cabinet officers, Seward to keep his hands off naval affairs, and Welles to watch Porter. Although Lincoln assumed all responsibility for the diversion of the Powhatan from Sumter, Welles never forgave Porter. He did recognize, however, that in Porter he had an asset, a brash, ambitious officer who would prove aggressive in battle. As for Porter, his inability to control events in Pensacola harbor taught him that he must command more than a ship to effect a victory; the single-ship actions of his father’s day would not suffice. Subsequent ineffectual blockading duty at the mouth of the Mississippi convinced him of the need to capture New Orleans, Louisiana.

The campaign for New Orleans was both a victory and a defeat for Porter, who overconfidently projected that a fleet of boats firing properly aimed army mortars could reduce the strong forts below within forty-eight hours, which allowed ships to run up and capture the city. The Union desperately needed a victory in the spring of 1862, particularly at New Orleans. Porter recommended that his foster brother Farragut lead the expedition. Porter, who received independent command of the mortar flotilla over the heads of senior officers, did not impress the rest of Farragut’s command, who looked down on his ragtag fleet and his use of merchant marine captains. Farragut himself had almost no faith in the mortar fleet but accepted it along with the assignment.6

Despite scientific placement of the mortars and highly accurate fire, the forts withstood six days of heavy bombardment. Farragut changed strategy and ran past the forts at night. Porter covered the attempt with mortar fire and received the forts’ surrender three days after Farragut took New Orleans. The mortar boats failed to destroy the forts, but Porter’s plan to capture New Orleans succeeded by adaption. The mortars kept Confederate gunners under cover, helped the fleet to pass the forts, and disabled several of the enemy’s best guns. More important, the psychological effect of Porter’s relentless attack caused the men in Fort Jackson to mutiny.7 After the surrender, the forts were found to be as strong as ever; Porter had won by perseverance. Lincoln recommended Porter for the thanks of Congress, both as a member of Farragut’s command and separately for “distinguished services in the conception and preparation of the means used for the capture of the Forts below New Orleans, and for highly meritorious conduct in the management of the Mortar Flotilla.”8

Following up the victory proved more difficult. Porter pushed for an attack on Mobile Bay, but the Navy Department ordered the fleet to Vicksburg, Mississippi. The city’s defending river guns were placed high on terraces, and Porter, minus his survey ship, had to aim his mortars by trial and error. It proved another futile effort. Farragut’s fleet successfully ran the Vicksburg batteries, but several vessels were badly damaged and Porter’s flotilla suffered heavy casualties while covering him. Low water and low morale led to dissension, as Farragut’s captains and Army Major General Benjamin F. Butler warred with Porter over credit for the New Orleans expedition. Soon, Porter wanted release from the Gulf Squadron so badly that he swore he would even prefer “to serve any where else in a yawl boat.”9

As politics played an increasing role in the war effort, Porter’s distaste for civilian meddling grew. He loathed political generals, such as Butler, yet used politics to advance his own career. He cultivated congressmen and developed close ties in the Navy Department with Assistant Secretary Fox, a trusted member of the Lincoln administration. When Porter angered Welles with outspoken criticism of the Union high command, the Secretary reassigned him to obscurity inspecting gunboats under construction at Cincinnati, Ohio. Faced with exile, Porter, the politician went over his superior’s head to Lincoln.

Lincoln twice before had given Porter major commands beyond his rank, the Powhatan and the mortar flotilla, with only partial success. Still, Porter had qualities that Lincoln could use. His persuasiveness and determination, along with Fox’s influence, convinced Lincoln that Porter was exactly the fighter he needed, for he gave him command of the Mississippi Squadron, the fleet above Vicksburg. Welles made the assignment grudgingly, noting that recklessness and energy were Porter’s primary qualifications.10

Porter’s new assignment had its good and bad points. Given the temporary and local rank of acting rear admiral, he controlled nearly all naval forces on the upper Mississippi, truly a partner with Farragut this time. Porter saw his elevation to rank and command over the heads of some eighty senior officers as retribution for his father’s suspension.11 To uphold his father’s image and to attain permanent rank, Porter had to succeed on the Mississippi, but Porter’s orders required him to cooperate in the capture of Vicksburg with Major General John A. McClernand, a distinctly political general with whom few people got along. The upper Mississippi was, moreover, the dumping ground for unpredictable commanders: Porter’s disreputable elder brother William David was there with a ship that he had named the Essex in memory of their father.

With funds, authority, and amenable subordinates, Porter reorganized his command and worked quickly to bring the fleet up to the Navy’s standards. Hearing nothing from McClernand, recruiting in Illinois, Porter offered his services to Major Generals Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman. Almost immediate affinity marked their relations.12 All three, professionals in a war of volunteers, disliked civilian interference, and their personalities, although distinctly different, meshed. Grant, the taciturn commander, worked well with Sherman, whose fiery, outspoken leadership complemented Grant’s more methodical style. Porter and Sherman were of the same mold: emotional, temperamental fighters, considered brilliant yet difficult; both unrelentingly energetic, they were impatient with slower men.

Nevertheless, their combination did not thrive from the start. Porter and Sherman assaulted the bluffs north of Vicksburg near Chickasaw Bayou. The loss of Grant’s supply line kept him from supporting Sherman, whose defeat in December 1862 proved that route to Vicksburg impossible. Porter, energetically supporting Sherman’s advance and worrying Confederate troops in the northern rivers, could do little more to effect a victory. McClernand’s arrival to command after the battle did not help.

McClernand brought to the field raw troops, a political appointment, a drive for personal fame, and a new bride. Porter disliked McClernand but agreed to support him in capturing Arkansas Post, where Sherman had planned to secure their supply line and achieve a victory. So determined was Porter to win that, when McClernand’s green troops left the post’s Fort Hindman in retreat, Porter boarded troops and prepared to take the fort himself. The surrender of the fort to Porter earned him Lincoln’s gratitude and another vote of thanks from Congress.13 Grant soon supplanted McClernand on the river and sought other routes through the swollen wintry swamps to Vicksburg.

In an effort to circumvent the batteries at Vicksburg, Grant’s army dug canals as Porter and Sherman unsuccessfully attempted to turn the northern flank of Vicksburg at Yazoo Pass and Steele’s Bayou. While Porter was upriver, two important vessels were captured by Confederates. Having nothing to send down to save them, Porter and his men rigged up a dummy monitor from an old barge and pork barrels. As it floated by in the dark, the monster frightened Vicksburg and stampeded the Confederates into destroying the Indianola to prevent her recapture. The effect of this ruse delighted Porter and he later used another dummy monitor to draw fire at Wilmington, North Carolina. The Navy Department fully appreciated Porter’s often unusual attempts to recover something from every loss.14

On 16 April 1863, under cover of darkness, Porter ran part of his fleet safely past the Vicksburg batteries. While Sherman feinted north to Haynes’ Bluff, Porter bombarded Grand Gulf and covered Grant’s crossing at Bruinsburg. With three days’ rations and no supply line, Grant set out overland to take Vicksburg. Porter, eager for action, destroyed the abandoned Grand Gulf, then assisted Farragut in a run up the Confederate supply line of Red River, capturing Fort De Russy and Alexandria, Louisiana. Grant and Porter opened a concentrated attack on Vicksburg on 22 May before settling into a siege.

Porter maintained Grant’s supply line, fired steadily on the city, fought guerrillas, and kept communications open to Washington. His passage of the Vicksburg batteries signaled the beginning of the end for the South. Confederate agents in London credited Porter with depressing their loan rate overseas. Porter’s achievement and the anticipated fall of Vicksburg dominated all conversation in Washington, with most observers believing that success at Vicksburg would decide the war.15 All Porter had to do for his coveted promotion was to support Grant, but he was too much of a fighter to wait patiently.

Within six weeks, Porter’s forces captured fourteen Confederate forts above Vicksburg, destroyed more than $2 million worth of Confederate naval stores and ships building on the Yazoo, and assisted in demoralizing Vicksburg with desertion propaganda and constant shelling. The city surrendered on 4 July 1863, and Porter immediately followed up the victory with a series of raids on inland waterways to Yazoo City and up the Red and White Rivers. Lincoln shared the spoils of victory with those most responsible; he promoted Porter to permanent rear admiral to date from the fall of Vicksburg.16

Porter’s last major campaign in the west, up the Red River in the spring of 1864, was the fiasco he expected it to be.17 Ordered to command the naval arm of the attack toward Shreveport, Louisiana, in cooperation with Major General Nathaniel P. Banks, Porter doubted that the river would provide sufficient draft for his vessels and that he would want to attempt operations with another political general. He was right on both counts. There was little coordination between the two commands. When Banks finally arrived at the rendezvous point over a week late, he found Porter and the Navy chasing prize cotton on the river. Once operations began, Porter sent his largest vessel upriver first, and she grounded, further delaying cooperation. The water fell rapidly, and Banks abandoned the Navy after his repulse at Sabine Crossroads, Louisiana.

Porter’s fleet had to fight its way downriver, but it was not the sort of fight he liked. Confederates with artillery ambushed the unprotected naval vessels. Porter got his fleet safely down to Alexandria, only to be stranded above the city in less than four feet of water. Without the support of Regular Army officers and an ingenious Army dam to float the boats over the bar, Porter would have been unable to extricate his command. The Army, the Navy, and his own men, by condemning Banks for his incompetency, preserved Porter’s reputation despite his costly errors of judgment.18

Porter, ordered from one disaster to another, had no time to make up for this defeat. Welles brought him east to command the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron off North Carolina, where the only remaining port supplying General Robert E. Lee’s army remained open at Wilmington. Porter used every stratagem he had learned in the war to tighten the blockade. He built up a powerful naval force, tightened cordon lines, and decoyed in $2 million worth of prizes, but only the capture of strategic Fort Fisher would close the port. Porter asked Grant for troops, and he agreed; when the Army finally appeared, Butler was leading. Porter, livid, treated Butler cordially, while privately damning Grant unfairly for sending the politician.19

Porter’s and Butler’s attack on Fort Fisher in December 1864 failed primarily because of distrust between the two commanders. Butler planned to destroy the fort by exploding an old ship loaded with gunpowder. Neither naval nor army engineers believed it would work, but Butler pressed, and Porter acquiesced. Butler kept most of his plans secret, which led to a long string of misunderstandings. The explosion failed, as expected.

Porter bombarded the fort to cover Butler’s landing, but Butler chose not to assault, as Porter hoped he would, or to entrench, as Grant ordered him to. Instead, he retreated, leaving behind several hundred men. Lincoln relieved Butler of command, and Brevet Major General Alfred H. Terry replaced him in a second attempt at the fort.

The stakes were high. Lee believed that Union capture of Forts Fisher and Caswell would force the evacuation of Richmond, Virginia. A second failure would sustain Butler. As insurance, in case the Army should fail him again, Porter drilled a landing party of sixteen hundred sailors and four hundred marines to storm the fort. Porter and Terry cooperated fully. Between the two men there were no secrets, and their determination effected a true combination.20

The attack of the naval landing party failed, but it diverted the fort’s defenders from the Army landing. Seven difficult hours later, the fort surrendered to Terry. The Confederates, forced to evacuate Caswell, fell back on Wilmington; pursued by Porter and Terry, they abandoned the last port in the Confederacy in January 1865. There was little left for the Navy to do. Porter went up the James River to Grant’s headquarters at City Point, southeast of Richmond, where his final war duties included attending strategy conferences on board the River Queen with Lincoln, Grant, and Sherman, and escorting the President around captured Petersburg, Virginia, and Richmond.

Most of Porter’s fame stems from his actions in combined operations. Although he was strategically clearsighted, his tactical plans, as first conceived, rarely worked. Luckily, he directed most maneuvers with enough personal autonomy to change course halfway and push the object through to success, at times by sheer force of will. Porter’s strength was in special operations, and his fighting personality accentuated his ability to follow up nearly every setback with a victory.

Porter’s campaigns depended on Army operations for success. At Chickasaw Bayou and then during the Yazoo Pass expedition, complete military cooperation would not overcome the barriers of geography, weather, and Confederate strength. Lack of coordination of forces up the Red River and in the first attack on Fort Fisher doomed the efforts from the start. Porter’s successes, notably at Arkansas Post, Vicksburg, and the second attempt at Fort Fisher, were due in no small part to the personalities of the commanders involved. Porter worked well with those who fought but poorly with those who hesitated.

The war made Porter both famous and controversial. His ambition, hunger for publicity and prize money, and swift advancement offended many whom he had surpassed. Peace brought a new set of problems for Gideon Welles, among them the question of what to do with Porter. He could not be sent to sea: his oft-stated belief that those countries that had supported the Confederacy should pay, particularly Great Britain, might lead him to provoke a foreign war. Porter never made any secret of his wish to command the U.S. Naval Academy and “get the right set of officers into the Navy.”21 His wide fame and belief in strong discipline could only help the troubled institution, which, although removed north, had barely survived the war intact.

The wartime Naval Academy had taken scant notice of changing technology and encouraged no physical activities. Drinking sprees were the prime extracurricular recreation, and an antiquated demerit system proved ineffectual in controlling student abuses. The academy was, in fact, only slightly more than a secondary school and taught midshipmen little that they could use to command ships.22 Porter believed that the academy’s purpose was to train officers for naval war. Installed as superintendent in 1865, he imprinted the academy with his own philosophy of practicality and professionalism; he was determined to make it the rival of West Point, whose graduates had impressed him with just those qualities.23

Porter began his tenure by strictly enforcing discipline. Common infractions included hazing, drinking, and taking “French leave,” none of which Porter took lightly. “The first duty of an officer,” he taught, “is to obey.”24 He proved to the midshipmen that he was serious. On a single day in October 1865, Porter issued orders requiring regular small-arms drills, dress parades, an oath of allegiance, and an eight-year service obligation. Further, he repealed all upper-class privileges for those forced to repeat a year and organized recreation times, cleverly keyed to begin as soon as drill obligations were properly completed. Porter supplemented the demerit system with practical punishments; as at West Point, guard duty and drill, assigned by severity of the offense, were used to enforce discipline.25

Before Porter’s arrival, few extracurricular activities had been organized to keep midshipmen out of trouble. Porter realistically decided that sports would give the young men an outlet for their frustrations. He built a gymnasium and especially encouraged fencing, boxing, bowling, shooting, and baseball. One never knew when Superintendent Porter might enter the ring to box the first classmen, and he especially hated losing a game of baseball. He encouraged competition within the academy and took his midshipmen to West Point for intercollegiate athletic trials.26

Porter also insisted on an honor system “to send honorable men from this institution into the Navy.”27 He designed uniforms, fostered music and drama clubs, invited midshipmen to test their gentlemanly behavior at tea, and led regular dancing parties. Lying and drinking earned his severest reproof, and he worked to close Annapolis brothels. He exhorted the midshipmen to act like officers and not “common sailors.” Unashamedly elitist, Porter even recommended denying admission to candidates who were cross-eyed, “common looking,” or too old. If he interfered with every aspect of the midshipmen’s private lives, at least he stood by them, and occasionally directed a redress in grades or accepted an apology in lieu of punishment.28

Porter redesigned the academy curriculum. He emphasized lectures over textbooks and required courses in seamanship, gunnery, naval construction, practical navigation, and steam engineering. Midshipmen learned to operate fully rigged ship models, drill with mortars, run and repair steam engines, strip sails on ships in record time, and give exhibitions of steam tactics and seamanship. Porter enlarged the department of steam engineering with a new building housing a working engine and several boilers and required three years of courses and a practical knowledge of steam engines of each graduate.

He successfully dabbled in politics to keep the academy afloat. Seeking support for a growing school during intense fiscal retrenchment, Porter invited politicians to review dress parades and exhibitions of naval tactics. He never failed to publicize the academy or to impress visitors. As a result of his political influence and the growing prestige of the academy under his direction, appropriations increased despite national budget cuts. With ideological renewal, congressional appropriations, and stringent economy, Porter physically rebuilt the academy: he spent $225,000 for buildings and alterations and purchased more than 130 acres of adjacent land.29

Despite Porter’s fame as an operational commander, his most enduring legacy was his whole philosophy of naval discipline and leadership, embedded in the academy and learned, he said, from his father. By strictly charging the midshipmen themselves with responsibility for their actions and the future of their institution, he made them aware of their elite status as naval leaders. Although Porter may have indeed “set the tone” for the modern-day Naval Academy, he did so by pinning that obligation on the midshipmen themselves, particularly on the first class.30

Porter restored pride to the academy. Grant and Sherman convinced him by their own examples that, despite West Point’s reputation as the premier engineering school in America, it did not necessarily turn out only engineers and theoreticians but men trained in the basics of the military profession: discipline, duty, honor, obedience, command—principles transcending service divisions. Such basic officer training also suited Porter’s daily expectations of foreign war.

Americans in peacetime have rarely supported a standing army or navy; the aftermath of the Civil War was no exception. Four years of expensive warfare put the United States ahead of its contemporaries in technology. Much of the rest of the world took America’s advances and improved upon them. Naval vessels of the war period were soon outdated, and few Americans supported their replacement. The naval stagnation following the Civil War probably could not have been avoided short of the war that Porter anticipated. Americans, if anything, were sick of war, and believed peace to be permanent.

The Army fared better than the Navy in the postwar world. Battlefield brevet and volunteer rankings faded away with war’s end and left in the service only those who had earned Regular Army promotions. The Army also had posts to maintain in the South and in the West, where Indians opposed the settlement by whites. Sherman, as lieutenant general and general, retained some active control over operations. Porter had no such power in his corresponding roles as vice admiral and admiral. With no offensive mission, the Navy had no role for ranking officers.

Congressmen, unwilling to fund advanced naval technology in peace, got only what they paid for—the U.S. Navy of their fathers, not that of their sons. Demobilization forced the Navy into a limited world mission until the 1890s, a rational approach to economic reality. Congress wanted a floating police force and saw no need to compete with European technology. Naval officers disagreed over the process of inevitable retrenchment and sought to protect their own definitions of a peacetime navy.31

Welles was proud of his success in directing the naval war and did not take kindly to any suggestions to share power in peace. Welles’s burgeoning naval bureaucracy greatly expanded the powers of the Navy’s bureau system. His raises in relative rankings and prerogatives for staff officers in support positions, and his recall of retired officers at high rank, bloated the officer class. Postwar retrenchment hit ranking line officers hardest, or so they perceived. With their ships laid up and promotion stagnant, staff officers and the bureau system, not Welles, bore the brunt of line officers’ blame. The line/staff controversy, renewed and confused by technological issues and exacerbated by Welles’s intransigence, erupted into war within the Navy. Behind the battles lay the real issue: who should control the Navy?

Porter’s role in the naval controversies created his image as an operational progressive and a technological reactionary, while his fighting personality defined his perception of the naval establishment. Porter believed that the Navy’s mission was war and that preparation for future wars was its peacetime occupation. Offensive purpose defined his view of naval administration, which he believed should remain strictly in the hands of experienced operational officers. “The Navy,” he declared, “will be dead for many years to come unless we have another war.”32

Technology, particularly steam engineering, was an important side issue in the controversy over control of the Navy. Neither Congress nor the American public would pay for advanced military technology. Between 1865 and 1869, the Navy’s budget declined 84 percent. A great portion of that budget went to the Bureau of Steam Engineering, where Benjamin Franklin Isherwood still spent money at wartime levels.33 Isherwood further offended line officers by seemingly placing the interests of machines over those of men. The attacks of Porter and the line officers on the status quo reflected the real anxieties of men who feared replacement by technology or by men of different abilities.

Porter did not hate engineers; he hated theoreticians—impractical, inflexible, wasteful men who built vessels but never sailed them—who understood machines but could not make them run. Isherwood’s prize ship, the Wampanoag, was Porter’s pet peeve, the symbol of technological inefficiency—the fastest ship in the world, built at an exorbitant cost, with insufficient room to house the men needed to run her, let alone those needed for naval maneuvers. That Isherwood, entrenched in the bureau, had sufficient power to control the direction of naval shipbuilding policy reaffirmed Porter’s belief that the bureau system was faulty. Despite Porter’s lengthy campaign to remove Isherwood and restore line supremacy, however, the two men remained friends and supported each other professionally in later years.34

Porter never hated Isherwood; his attacks were a means to an end. Porter wanted to revive and lead his father’s old Board of Navy Commissioners and made several unsuccessful attempts to have Congress restore it. His insistence on the importance of line officers controlling the Navy had led him to replace staff officers with line officers in teaching positions at the academy.

In 1869, when Grant assumed the presidency, he appointed Adolph E. Borie as Secretary of the Navy and assigned Porter to special duty as his assistant, a rudimentary chief of naval operations. Porter took personal control of the Navy Department at the most visible levels and immediately issued a blizzard of sweeping general orders, twelve in one day, over Borie’s signature. He reduced staff prerogatives and defined those of the line; he redesigned uniforms to reflect the staff’s lower status and ranking. Further orders limited the power of the bureaus to internal matters, consolidated squadrons, renamed vessels, and organized a line board of ship examiners. Porter’s most controversial orders were among his last. He delayed reducing the relative rankings of the staff officers to pre-Welles levels until a legal basis for it could be found. His orders requiring full sail power in all naval ships and strictly limiting the use of coal, along with the condemnation of Isherwood’s ships by a board of line officers, were the parting shots of Porter’s short administration.35

Behind Porter’s attempted reforms of 1869 lay the threat of war with Great Britain. American diplomats were then negotiating reparations due the United States for Britain’s assistance to the Confederacy. Porter wanted war, especially with Great Britain, and he wanted a navy prepared for war. At the Naval Academy he prepared men for command and for war; in the department, he attempted to do the same. He endeavored to restore unity to a fragmented command structure by returning control to the Secretary and removing it from the bureaus. The Secretary, or his assistant, Porter, would command the naval forces in any coming war. Unfortunately for Porter, his war did not materialize. His reputation was the major casualty of his own administration.

Porter knew that the U.S. Navy could not match the Royal Navy, but he insisted on strengthening all natural advantages. General Orders 128 and 131 did no more than adopt international naval policies. British regulations requiring sails and restricting coal use were far harsher than Porter’s—coal was expensive and engines were inefficient in 1869. In declaring steam auxiliary to full sail power, Porter capitalized on the natural resources of men and wind while directly overturning Welles’s emphasis on steam over sails. Porter’s orders prescribed readiness and constant exercise. He wanted the Navy to be ready for immediate action with maximum efficiency. A master at improvising, Porter convinced Congress to fund Naval Academy expansion through a combination of politics, prestige, and stringent recycling. He hoped, by using similar tactics, to convince Congress to fund a real naval fighting force.

Borie never wanted to run the Navy and was happy to sign over full authority to Porter, who issued orders in Borie’s name until the furor over Porter’s arbitrariness, impatience, and high-handedness made Borie’s life miserable. After three months, Borie resigned, and Grant replaced him with George Robeson, who eased Porter from his position of power. Within one year, Porter’s influence had so declined that he claimed he did not enter the Navy Department’s headquarters more than four times between 1870 and 1876.36

Despite strong political opposition, Porter—promoted to admiral in 1870—remained on active duty until his death in 1891. During those last twenty-one years he wrote regular advisory reports, sat on inspection boards, and worked to develop naval higher education. His few duties were unimportant, and his opinions were generally ignored. Unhappy with semiretirement, he still sought to influence naval policy and continued to send in an unwanted yearly report.37 Despite Porter’s advocacy of a stronger coastal defense, he retained his vision of offensive naval purpose. His reports, in the form of incomplete, repetitive letters addressed to successive secretaries, sought immediate, effective answers to contemporary problems. Read as statements of policy, they seem foolish today; in the context of their intent, they are extremely revealing.

Porter, the product of a maritime nation, lived in an emerging industrial age. The Civil War destroyed America’s commercial shipping industry whereas it strengthened the British carrying trade. The United States failed to recover its oceanic trade or its maritime reserve during Porter’s lifetime. From 1870 until 1889, Porter fought a losing battle to restore U.S. maritime eminence, which enhanced his image as a reactionary against industrialization. He appreciated new technology but thought the training of men as important as the building of ships. Nothing in Porter’s experience prepared him for an age when the needs of ships would outweigh those of men.

Machine dominance was by no means certain until after his death. Science and technology advanced slowly; not until 1880 were the first and second laws of thermodynamics usable in creating efficient steam engines. By 1884, steam predominated, which led the Navy to reduce sail power and, by 1889, to begin establishing the international fuel depots that Porter believed were necessary for a steam navy. Only as technology and foreign policy changed did Porter’s advocacy of coastal defense and commerce raiding appear outdated; even Alfred Thayer Mahan supported such a program in 1885. Until instant obsolescence of naval vessels was controlled, the Navy remained transitional.38

What Porter advocated was naval diversification. He wanted improved forts; rams and monitors for defense; fast commerce raiders to cripple future enemy shipping; advanced submarine torpedo-firing boats for both offense and defense; and, ultimately, steel ships.39 He opposed rebuilding the Navy around only one type of ship. Rather than returning the Navy to the age of sail, he sought to keep it flexible. He advocated constant exercise of existing ships and squadrons, development of new vessels, education of all naval personnel, modernization of armament, and subsidization of a new merchant marine. The 1874 sea trials in the West Indies following the Virginius crisis forced Porter into a more defensive position and convinced him that what little navy Congress allowed would be destroyed in the inevitable war; however, by 1881, he spoke of planning “a navy for home defense, but, of course, in time of war we should not be willing to rest quietly guarding our coast.”40

On the eve of the New Navy, Porter reargued diversity, defense, and dedication and reasserted the necessity of rebuilding America’s lost prestige as a maritime nation. He urged officers at the struggling Naval War College to exchange ideas about the new types of strategy and tactics needed for the battles of the future. Porter decried Congress’s attempts to rebuild the Navy overnight, quoting from Mirabeau to express his own naval philosophy: “You cannot have a navy without sailors, and sailors are made through the dangers of the deep, from father to son, until their home is on the wave. You cannot build up a navy at once by a simple act of legislation.”41

Despite his high rank, Porter had no voice in the Navy. Embittered, he turned to writing to gain an audience. His first and best work, Memoir of Commodore David Porter (1875), attempted to justify his father’s career as well as his own. His later works, particularly his Incidents and Anecdotes of the Civil War (1885) and Naval History of the Civil War (1886), rank with some of his personal correspondence in the magnitude of their inaccuracy. Porter fired words like grapeshot, indiscriminately, in haste, and in often regretted rash comments.

The deaths of Porter and Sherman, one day apart, ended an era. Of the Union heroes of the Civil War, they were the last of the high command. Porter was excoriated by navalists of an expansionist, steam-powered world for advocating sails and a defensive strategy; by surviving political generals for his hatred of them; and by the many men with whom he argued in print in the pages of the various naval and maritime journals. They either damned him in print for his personality or mentioned him only for his operational victories.

Commodore Porter’s sons never escaped their father. William David Porter, disinherited by his family, named his ship the Essex and, at his death, was buried next to his father, who had actively loathed him.42 David Dixon Porter never saw the restoration of the maritime splendor of his father’s age, but he surrounded himself with mementos of the commodore and retained many of his sociable habits. He easily eclipsed his father in the happiness of his relationships with his friends, his wife, and his children, but the Porter name advanced his career when his own actions failed to. Despite his rank and achievements, he never quite believed that his career was more successful than his father’s.

One of Porter’s subordinates said that it was a naval tradition that “the Porters were all brave and all braggarts,” and David Dixon Porter was no exception.43 He organized chaos into order, executed seemingly impossible tasks, cooperated well with anyone who respected him and gave him sufficient credit, and implacably hated those who did not. His boundless energy and pursuit of knowledge invigorated the Naval Academy. He helped found the U.S. Naval Institute and an experimental torpedo school (the progenitor of the Naval Underwater Systems Center), and influenced Stephen B. Luce’s determination to make the Naval War College the home for the study of the art of war at sea.44 Porter lived in the ages of both sail and steam, wooden ships and steel, and appreciated the qualities of each. His fighting spirit, the legacy of David Porter, for better or worse, affected all that he did.

David Dixon Porter has always provoked much comment in print. His associations with many of the nineteenth-century military and political figures have caused much speculation, and opinions concerning each facet of his life are often conflicting. The best and standard biography of Porter is Richard Sedgewick West, Jr.’s The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter, 1813–1891 (New York, 1937), which, although favorable, is realistic about many of his shortcomings throughout the Civil War period. James Russell Soley’s Admiral Porter (New York, 1903) and Noel Bertram Gerson’s Yankee Admiral: A Biography of David Dixon Porter (New York, 1968) provide interesting insights but lack documentation. Porter’s childhood is best illustrated in David F. Long’s Nothing Too Daring: A Biography of Commodore David Porter, 1780–1843 (Annapolis, Md., 1970). The “Camel Corps” of the 1850s has been the subject of several short books and articles, and, as it pertains to Porter, is outlined in Malcolm W. Cagle’s “Lieutenant David Dixon Porter and His Camels,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 83 (December 1957): 1327–33.

Studies of the war period abound with references to Porter’s activities, but West’s Second Admiral remains the best source for the war as it relates to Porter. Porter’s war career is ably related in several articles, particularly William N. Still, “‘Porter . . . Is the Best Man’: This Was Gideon Welles’s View of the Man He Chose to Command the Mississippi Squadron,” Civil War Times Illustrated 16, no. 2 (1977): 5; a chapter of Caroll Storrs Alden and Ralph Earle, Makers of Naval Tradition, rev. ed. (Boston, 1943); and Richard West’s “The Relations between Farragut and Porter,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 61 (July 1935): 985–96. Ludwell H. Johnson’s Red River Campaign: Politics and Cotton in the Civil War (Baltimore, 1958) goes beyond the normal campaign history to describe the outside influences that affected this operation, particularly as they relate to individuals, and ably describes Porter’s errors of judgment.

Porter’s postwar career is best discussed in Kenneth J. Hagan, American Gunboat Diplomacy and the Old Navy, 1877–1889 (Westport, Conn., 1973) and “Admiral David Dixon Porter: Strategist for a Navy in Transition,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 94 (July 1968): 139–43; Charles O. Paullin, “A Half Century of Naval Administration in America, 1861–1911: Part IV. The Navy Department under Grant and Hayes, 18691881,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 39 (1913): 736–60; Lance C. Buhl, “Mariners and Machines: Resistance to Technological Change in the American Navy, 1865–1869,” Journal of American History 61 (1974): 703–77; Park Benjamin’s The United States Naval Academy (New York, 1900); and Edward William Sloan Ill’s Benjamin Franklin Isherwood, Naval Engineer: The Years as Engineer in Chief, 1861–1869 (Annapolis, Md., 1965). Porter’s own writings, written mostly in reaction to his postwar inactivity, should not be relied on for specific facts, although they reveal clearly his personality.

1. The chaotic Porter family relationships are best described in David F. Long, Nothing Too Daring: A Biography of Commodore David Porter, 1780–1843 (Annapolis, Md., 1970), and Richard Sedgewick West, Jr., The Second Admiral: A Life of David Dixon Porter, 1813–1891 (New York, 1937). For David Dixon Porter’s idealized view of his father, see his Memoir of Commodore David Porter, of the United States Navy (Albany, N.Y., 1875).

2. West, Second Admiral, 63.

3. Lincoln to Porter, 1 April 1861, Offical Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, ser. 1, vol. 4, 108–9 (hereafter cited as ORN). Also, see Lincoln to Welles, 1 April 1861, in Roy P. Basler, ed., Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick, N.J., 1953–1955), 4:318–19. The appointment, over Lincoln’s signature, of Samuel Barron to head the Office of Detail received much attention after the war by anti-Porter factions, who saw in it an attempt by Porter to place a Southerner, and one who ultimately sided with the Confederacy, in a place of importance in the Navy Department. In reality, both Lincoln and Welles were also in the process of appointing to responsible commands men who would later turn Confederate. Welles certainly detested Porter’s attempt to alter Navy Department policy, but he made a public issue of Porter’s selection of Barron only after the war, when politics intervened. Porter had as many Southern connections as most officers in this war, but even Welles admitted Porter proved his loyalty to the Union cause in action. Barron’s appointment, in Meigs’s handwriting, with Porter’s postscript, had the approval of Secretary of State Seward. For Welles’s postwar view, see Howard K. Beale and Alan W. Brownswood, eds., Diary of Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy under Lincoln and Johnson, 3 vols. (New York, 1960), 1:16–21, and Gideon Welles, “Facts in Relation to the Expedition Ordered by the Administration of President Lincoln for the Relief of the Garrison in Fort Sumter,” The Galaxy 10 (November 1870), reprinted in Selected Essays by Gideon Welles: Civil War and Reconstruction, compiled by Albert Mordell (New York, 1959).

4. Porter to [A. H. Foote], [5 April 1861] ORN, ser. 1, vol. 4, 111–12; Seward to Porter, 6 April 1861, ibid., 4:112; and Porter to Seward, 6 April 1861, ibid.

5. Porter to [Captain H. A. Adams], 24 August 1862, ibid., 130.

6. West, Second Admiral, 114; Richard West, “The Relations between Farragut and Porter,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 61 (July 1935): 989; and Loyall Farragut, The Life and Letters of Admiral Farragut, First Admiral of the United States Navy (New York, 1879), 210.

7. Lieutenant Colonel Edmund Higgins, CSA, to Lieutenant William M. Bridges, CSA, 30 April 1862, David Dixon Porter Papers, Library of Congress (hereafter cited as DDP, DLC).

8. Lincoln to Senate and House of Representatives, 14 May 1862, in Basler, Collected Works of Lincoln, 5:215n, and 11 July 1862, in ibid., 315–16.

9. Porter to Fox, 22 June 1862, DDP, DLC.

10. David Dixon Porter, Incidents and Anecdotes of the Civil War (New York, 1885), 120–22; and Beale and Brownswood, Diary of Gideon Welles, 1 October 1862, vol. 1, 157–58; ibid., 10 October 1862, 1:167. Welles glumly recorded his advancement of Porter in his diary, noting many more of Porter’s negative than his positive qualities, and questioning Porter’s ability to succeed, sighing, “If he does well I shall get no credit; if he fails I shall be blamed.” Ibid., 1:157–58. Given his negativism and Porter’s distinct mission to assist Lincoln’s special forces under Major General John A. McClernand, it is more likely that Fox and Lincoln decided on Porter’s assignment and Welles acquiesced. Welles was later able to impress Lincoln with the first news of the fall of Vicksburg, making Welles briefly Porter’s strong supporter.

11. William N. Still, “‘Porter . . . Is the Best Man’: This Was Gideon Welles’s View of the Man He Chose to Command the Mississippi Squadron,” Civil War Times Illustrated 16, no. 2 (1977): 5.

12. Porter to Fox, 17 October 1862, in Robert Means Thompson and Richard Wainwright, eds., Confidential Correspondence of Gustavus Vasa Fox, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, 1861–1865, 2 vols. (New York, 1920), 2:140; Porter to Fox, 21 October 1862, in ibid., 2:143; and Sherman to [John Sherman], 14 December 1862, in Rachel Sherman Thorndike, ed., The Sherman Letters: Correspondence between General Sherman and Senator Sherman from 1837 to 1891 (New York, 1969 [1894]), 174–75.

13. William T. Sherman, Memoir of William T. Sherman Written by Himself, 2 vols. (New York, 1875), 1:297; Lloyd Lewis, Sherman, Fighting Prophet (New York, 1932), 257–61; West, Second Admiral, 199; Fox to Porter, 6 February 1863, in Thompson and Wainwright, Confidential Correspondence of Fox, 2:156; Lincoln to Congress, 28 January 1863, in Basler, Collected Works of Lincoln, 6:82; and Lincoln to Congress, 19 February 1863, in ibid., 6:111–12.

14. Porter to Welles, 10 March 1863, in War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (hereafter cited as OR), ser. 1, vol. 24, pt. 3, 97–98; Porter to Fox, 19 February 1864, in Thompson and Wainwright, Confidential Correspondence of Fox, 2:200–01; and Fox to Porter, 16 July 1863, in ibid., 2:185.

15. Henry Hotze to Judah P. Benjamin, 9 May 1863, ORN, ser. 2, 3:760; Hotze to Benjamin, 14 May 1863, ibid., 3:768; West, Second Admiral, 229–30.

16. West, Second Admiral, 231–32; and Lincoln to the Senate, 8 December 1863, in Basler, Collected Works of Lincoln, 7:56–57.

17. Porter anticipated problems with the water level before the expedition. See Sherman to Grant, 4 January 1864, in John Y. Simon, ed., Papers of Ulysses S. Grant (hereafter cited as PUSG), 14 vols, to date (Carbondale, I11., 1967– ), 10:20. Porter also knew Banks and had previously noted his unwillingness to assist other commands. See, for example, Porter to Grant, 14 May 1863, OR, ser. 1, vol. 24, pt. 3, 309, and Porter to Grant, 10 June 1863, PUSG, 8:335.

18. Ludwell H. Johnson, Red River Campaign: Politics and Cotton in the Civil War (Baltimore, 1958), 241; and Porter to Sherman, 14 April 1864, OR, ser. 1, vol. 34, pt. 3, 153–54. Examples of army opinions on Banks are in PUSG, 10:340, 351–52, and 429.

19. Porter’s condemnation of Grant, soon regretted, was printed in newspapers and an anti-Porter tract in 1876. See Porter to Welles, 24 January 1865, in F. Colburn Adams, High Old Salts: Stories Intended for the Marines, but Told before an Enlightened Committee of Congress (Washington, D.C., 1876), 32–36.

20. West, Second Admiral, 288; Grant to Terry, 3 January 1865, PUSG, 13:219; and Porter to Grant, 14 January 1865, ibid., 13:227.

21. Porter to Fox, 28 March 1862, Thompson and Wainwright, Confidential Correspondence of Fox, 2:95.

22. Park Benjamin, The United States Naval Academy (New York, 1900), 266–71. Also, see Charles Todorich, The Spirited Years: A History of the Antebellum Naval Academy (Annapolis, Md., 1984).

23. Porter to Welles, 25 September 1866, U.S. Navy Department, Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1866, 76 (hereafter cited as Annual Report, [year]); and James Russell Soley, “Eulogy,” in A Memorial of David Dixon Porter from the City of Boston (Boston, 1891), 63.

24. Porter Order, 14 October 1865, in Record Group (RG) 405, No. 48, Press Copies of Orders Issued by the Superintendent, 1865–1869, National Archives (hereafter cited as RG 405: Superintendent’s Orders), 1:19–20.

25. Porter to Welles, 18 October 1865, RG 45, No. 34, Letters from Commandants of Navy Yards and Shore Stations, Naval Academy, National Archives (hereafter cited as RG 45: Naval Academy Letters), 246:48; Porter Order, 24 October 1865, RG 405: Superintendent’s Orders, 1:43; and Porter Order, undated, ibid., 1:52.

26. Benjamin, Naval Academy, 266–67; Todorich, Spirited Years, 39; Walter Aamold, “Athletic Training at the Naval Academy,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 61 (October 1935): 1562.

27. Porter Order, 21 November 1865, RG 405: Superintendent’s Orders, 1:82–83.

28. Porter Order, 11 January 1866, ibid., 1:125–26; Porter Order, 2 June 1867, ibid., 1:540–42; Porter to Welles, 19 December 1865, RG 45: Naval Academy Letters, 246:110; Porter Special Order, 24 October 1865, RG 405: Superintendent’s Orders, 1:45; and Porter Order, 21 November 1865, ibid., 1:82–83.

29. Report of Board of Visitors, 4 June 1869, Annual Report, 1869, 137.

30. Porter Order, [30] September 1867, RG 405: Superintendent’s Orders, 1:582–88.

31. Lance C. Buhl, “Maintaining An American Navy, 1865–1889,” in Kenneth J. Hagan, ed., In Peace and War: Interpretations of American Naval History, 1775–1984 (Westport, Conn., 1978), 145–70.

32. Porter to John Barnes, 25 February 1869, quoted in Peter Karsten, The Naval Aristocracy: The Golden Age of Annapolis and the Emergence of Modern American Naval-ism (New York, 1972), 266.

33. Charles O. Paullin, “A Half Century of Naval Administration in America, 1861–1911: Part IV. The Navy Department under Grant and Hayes, 1869–1881,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 39 (1913): 744; Edward William Sloan III, Benjamin Franklin Isherwood, Naval Engineer: The Years as Engineer in Chief, 1861–1869 (Annapolis, Md., 1965), 199.

34. Sloan, Isherwood, 240.

35. General Order No. 89, 10 March 1869; General Orders Nos. 90, 91, 94, 95, 96, 97, and 99, 11 March 1869; General Order No. 105, 13 March 1869; General Orders Nos. 108 and 109, 15 March 1869; General Order No. 124, 15 May 1869; General Order No. 130, 15 June 1869; and Circular, “Duties of Bureaus to Commence May 15, 1869,” all in RG 45, No. 43, ‘Directives,’ DNA.

36. Although later navalists, notably Harold Sprout and Margaret Sprout, The Rise of American Naval Power, 1776–1918 (Princeton, N.J., 1939), and Samuel W. Bryant, The Sea and the States: A Maritime History of the American People (New York, 1947), claim that Porter controlled naval policies under Robeson, there is no evidence to support this. Porter’s lack of influence in naval matters is reported in Paullin, “A Half Century of Naval Administration,” 750, and is mentioned in Porter to William C. Whitney, 30 November 1885, Annual Report, 1885, 280.

37. Porter to William H. Hunt, 19 June 1881, Annual Report, 1881, 95.

38. Lance C. Buhl, “Mariners and Machines: Resistance to Technological Change in the American Navy, 1865–1869,” Journal of American History 61 (1974): 709; Kenneth J. Hagan, American Gunboat Diplomacy and the Old Navy, 1877–1889 (Westport, Conn., 1973), 19–27; and Karsten, Naval Aristocracy, 312, 334.

39. Porter to Hunt, 19 June 1881, Annual Report, 1881, 102, 216; and Porter to William E. Chandler, 19 November 1883, Annual Report, 1883, 390–405. Porter early advocated abandonment of wood for all-metal shipbuilding. See “Lecture delivered before the 2nd Class of Midshipmen at the U.S. Naval Academy, January 22nd, 1870,” DDP, DLC.

40. Porter to Hunt, 19 June 1881, Annual Report, 1881, 103.

41. Porter to the Secretary of the Navy, 6 July 1887, Annual Report, 1887, 53.

42. Dana M. Wegner, “Commodore William D. ‘Dirty Bill’ Porter,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 103 (February 1977): 44, 49.

43. Typescript, “Autobiography of Joseph Smith Harris,” 12 August 1908, Naval Historical Foundation, Washington, D.C.

44. John B. Hattendorf, B. Mitchell Simpson III, and John R. Wadleigh, Sailors and Scholars: The Centennial History of the U.S. Naval War College (Newport, R.I., 1984), 5–6, 17; and Ronald Spector, Professors of War: The Naval War College and the Development of the Naval Profession (Newport, R.I., 1977), 21.