CHAPTER 3

Invasion

(Barbarossa: December 1940–September 1941)

The news that the Germans were attacking along the western frontier and bombing cities did not at all surprise General Georgi Zhukov when he was told in Moscow at 0330 hours on 22 June. Even so, as Chief of the General Staff, he did not relish fulfilling the order of Marshal Semyon Timoshenko, the Commissar for Defence, to inform Stalin. After several failed attempts to raise somebody on the telephone at the General Secretary’s dacha, a drowsy duty officer picked up and said that Stalin was asleep. ‘Wake him up immediately,’ Zhukov insisted. ‘The Germans are bombing our cities.’ A couple of minutes passed before Stalin took the receiver and was told the news. His silence was that of a man struggling to interpret the reality of an event that he had persuaded himself would not happen. ‘Do you understand me?’ Zhukov inquired, but the line remained quiet. Several seconds passed before Stalin seemed to regain his poise. ‘Go to the Kremlin with Timoshenko,’ he ordered. ‘Tell Poskrebyshev [his secretary] to summon all Politburo members.’ Stalin remained unconvinced that an invasion had begun even as he was sped through the deserted Moscow streets to his office. How could he have been hoodwinked? Yet shortly after his arrival, Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov, having met with an ashen-faced German Ambassador, told Stalin, ‘The German government has declared war on us.’ Stalin sank down into his chair and after a long and thoughtful pause proclaimed, ‘The enemy will be beaten all along the line.’

The shattering news was broadcast to the population at noon when the voice of a nervous Molotov trilled:

Citizens and Citizenesses of the Soviet Union! Today, at four o’clock in the morning, without addressing any grievances to the Soviet Union, without declaration of war, German forces fell on our country, attacked our frontiers in many places and bombed our cities . . . an act of treachery unprecedented in the history of civilized nations . . . The Red Army and the whole nation will wage a victorious Patriotic War for our beloved country, for honour, for liberty . . . Our cause is just. The enemy will be beaten. Victory will be ours.

In failing to announce the full scale of the disaster and by calling upon the population’s devotion to their nation rather than the Party, Molotov struck a patriotic chord while allowing a stunned people to absorb the information. As they did so, the decision makers reacted to the German invasion by mobilizing the armed forces and putting their faith in the Molotov Line and local counterattacks. Stalin had not been surprised by Hitler’s invasion; he had been astounded.

Hitler’s determination to destroy the Soviet Union was multi-faceted and all consuming. His ideological opposition to the Communist state verged on the maniacal: ‘One day,’ Hitler affirmed, ‘the Russians, the countless millions of Slavs, are going to come. Perhaps not even in ten years, perhaps only after a hundred years. But they will come.’ A pre-emptive strike to destroy Bolshevism would remove the threat while also providing the land and other resources that the Nazis so coveted. These ‘immeasurable riches’ were not only essential for the Reich to expand but also, by the end of 1940, to maintain previous gains and remove a military threat. Hitler fervently believed that the invasion of the Soviet Union was not a whim, but a necessity, and later said: ‘For us there remained no other choice but to strike the Russia factor out of the European equation.’ Irresistibility and need came together to make an invasion the critical aim of the Nazi regime and the focus of German strategy. In 1939 Hitler announced to a League of Nations official:

Everything that I undertake is directed against Russia. If those in the West are too stupid, and too blind to understand this, then I shall be forced to come to an understanding with the Russians to beat the West, and then, after its defeat, turn with all my concerted force against the Soviet Union.

To the blinkered Führer, the defeat of the Soviet Union was a panacea that would make Germany unassailable in Europe.

In late July 1940, while Germany was still basking in its success in Western Europe, Hitler announced to colleagues that he wanted to launch an invasion of the Soviet Union in the spring of the following year ‘to smash the state heavily in one blow’. The High Command had more time to prepare for the invasion than for any other offensive of the war. Preliminary planning began immediately and led to Hitler publishing Directive No. 21 on 18 December. Announcing that preparations were to be completed by 15 May 1941, the Directive stated that ‘[t]he mass of the Russian Army is to be destroyed in daring operations by driving forward deep armoured wedges, and the retreat of units capable of combat into the vastness of Russian territory is to be prevented.’ The final objective was to be ‘the general line Volga–Archangel’ and was to be achieved within five months. Hitler believed Moscow itself to be ‘of no great importance’ in the defeat of the Soviet Union; he sought a victory to the west of the capital, having denuded Stalin of both defenders and resources. The Red Army was to be encircled and liquidated within 250 miles of the start line and in around eight weeks. Speed was the essential ingredient in the plan and the military placed their faith in blitzkrieg to catch Stalin cold and ensure that Germany was not dragged into a protracted struggle for which she was ill-prepared.

The offensive was codenamed Barbarossa after Frederick I Barbarossa (Red Beard), the twelfth-century German emperor who led a crusade against Saladin’s Muslim armies. In 1941, Hitler’s crusade against Bolshevism, Jews and other ‘radical elements’ would show no mercy as his soldiers occupied captured territory and exploited it, having subjugated the useful ‘inferior population’ and exterminated the rest. Yet the wide-ranging nature of German ambitions provided ample potential for confusion, inefficiency and contradiction in their pursuit. There was no one single, achievable aim identified by Hitler, no tri-service planning, and plenty of opportunities for Clausewitzian ‘friction’ to unhinge the best efforts of the Wehrmacht to deliver the aims in the timeframe. Barbarossa was a smorgasbord of an operation, a mixture of ideological, military, economic and territorial aims upon which Hitler could feast but which his planners would struggle to pull together and his field forces would struggle to carry out. Senior commanders, such as Colonel-General Franz Halder, Chief of the Army Staff, were aghast at the scope of the operation and feared that Hitler had eschewed practical considerations for ‘a mystical conviction of his own infallibility’.

Barbarossa was to open with 3.8 million German forces, supported by 3,350 tanks and 7,200 artillery pieces, attacking in three army groups to a depth of between 500 and 900 miles across a 1000 mile front. Army Group North, commanded by General Ritter von Leeb, was to push through East Prussia and the Baltic states to Leningrad; General Fedor von Bock’s Army Group Centre was to encircle Minsk, Smolensk and then Moscow; Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt’s Army Group South, separated from Bock by the Pripyat Marshes, was to cross the plains of southern Russia and the Ukraine to Kiev and then to Rostov. Bock’s formation was to provide the main effort along the best roads, and while plunging towards their own ‘vital objectives’, the army groups on either side were to provide flank protection and ensure that the enemy, naturally drawn to the defence of the capital, was defeated before the advance reached Moscow. Army Group Centre would, therefore, benefit from two panzer armies while Leeb and Rundstedt received one each. Bock was also supported by 1,500 of the 2,770 available aircraft from the Luftwaffe, which was trained and configured specifically for ground-support operations. Blitzkrieg was to be given the opportunity to deliver Hitler another remarkable victory.

German strategy and operational methods were based on the rapid defeat of the Soviets, specifically to avoid the protracted campaign that Hitler was not prepared to fight. The Soviet Union had a population of 190 million compared with Germany’s 80 million in 1941, so there was no desire to become involved in an attritional conflict, although planners struggled to see how the Soviets could be defeated in a matter of a few weeks. They feared that the difficult terrain, vast distances and inhospitable Soviet autumn and winter weather would have a far larger part to play in the outcome of the campaign than Hitler wanted to acknowledge. The logisticians fretted about the feeble Soviet communications infrastructure, the roads of compacted earth, the incompatible railway lines that rendered German locomotives and rolling stock useless, and the general lack of essential resources ranging from spare engine parts to attacking formations. There were too few panzer divisions for such an ambitious offensive, for example, and so in typical ‘make do and mend’ style Hitler merely halved the number of tanks and supporting assets in each existing formation in order to double their number. Yet even this drastic move did nothing to attend to the lack of motorization in the vast majority of the army – less than 17 per cent of the German ground forces were motorized – which would cause it to lag behind the spearheads. Hitler’s army was one that, despite its close relationship with fast-moving armoured warfare, relied extremely heavily on boot leather and horse-drawn transport to advance east. Some 625,000 hungry and thirsty horses were consequently prepared for Barbarossa and just 600,000 vehicles, consisting of a toe-curling 2000 variants. These vehicles were also hungry and thirsty, but the lack of spare parts, petrol, oil and lubricants did not bode well for the Wehrmacht’s ability to keep them moving. Barbarossa was a logistical nightmare. Indeed, in December 1940 Major-General Frederich Paulus, the head quartermaster, conducted a wargame which demonstrated that the operation’s logistic arrangements would collapse before they reached the upper Dnieper. Hitler was unmoved. The army was admirably imbued with flexibility and opportunism, and the necessarily ‘Gradgrindist’ planners were under such pressure that they had to fudge critical issues and ignore unhelpful information.

The generals were justifiably concerned at Hitler’s lack of consultation about the application of force, his oversimplification of a whole series of massively complicated issues. It seemed that the Führer’s mind was already made up and no experts or documents were likely to change it. Fritz Wiedemann, a member of Hitler’s personal staff, recalls: ‘Hitler refused to let himself be informed . . . How can one tell someone the truth who immediately gets angry when the facts do not suit him?’ However, recalling their previous deep-seated concerns about earlier successful campaigns, the generals offered very little resistance to plans that they instinctively believed to be flawed. Thus, when Hitler said that with the launch of Barbarossa ‘Europe will hold its breath’, the same was true of many of his senior officers. Colonel-General Heinz Guderian, commander of Bock’s Second Panzer Army, received a map brief from his staff. ‘I could scarcely believe my eyes,’ he later wrote, ‘[and] made no attempt to conceal my disappointment and disgust.’ Knowing history, Guderian was well aware that others had tried to overwhelm Russia and failed:

Renewed study of the campaigns of Charles XII of Sweden and of Napoleon I clearly revealed all the difficulties of the theatre to which we threatened to be committed; it also became increasingly plain to see how inadequate were our preparations for so enormous an undertaking. Our successes to date, however, and in particular the surprising speed of our victory in the West, had so befuddled the minds of our supreme commanders that they had eliminated the word ‘impossible’ from their vocabulary.

Far from believing that it was ‘impossible’ to defeat the Soviet Union rapidly, Hitler was confident of victory. His successful, large, well-educated, carefully trained and competently led military machine would, he was sure, prove too strong for its ‘subhuman’ adversaries. The Führer further fortified himself with the belief that the Soviet Union was economically, industrially and physically backward, a retard nation with a purged army equipped with obsolete weaponry. ‘You only have to kick in the door,’ Hitler declared, ‘and the whole rotten house will come crashing down.’

The Soviet force that would have the task of stopping the German invasion amounted to nearly 5 million troops in 20 armies consisting of 303 divisions with 19,800 artillery pieces and 11,000 tanks. The Red Air Force had 9,100 aircraft. Although an awesome military machine on paper, it was riddled with inadequacies brought about by the effects of Stalin’s terror, rapid expansion and lack of investment. Thus, although senior staff officers advocated a pre-emptive strike on Germany – Deputy Chief of Operations General Aleksandr Vasilevsky wrote in May 1941: ‘I consider it necessary not to give the initiative to the German command under any circumstances, to forestall the enemy in deployment and to attack the German army at the moment when it is still at the deployment stage’ – Stalin recognized that the army was not ready for any such move. Zhukov, who was appointed Chief of the General Staff in January 1941, wrote in his memoirs:

Two or three years would have given the Soviet people a brilliant army, perhaps the best in the world . . . [but] history allotted us too small a period of peace to get everything organized as it should have been. We began many things correctly and there were many things we had no time to finish. Our miscalculation regard[ing] the possible time of fascist Germany’s attack told greatly.

New mechanized corps were formed but industry and infrastructure struggled to keep pace with their voracious appetite for resources and so they were short of men, trucks and tanks. Zhukov argued that 16,600 of the latest tanks were required within a total force of 32,000 tanks to equip fully the mechanized corps, but just 7000 tanks were delivered between January 1939 and June 1941, and of these just 1,861 were new types, including the KV-1 and T-34. The 125 new infantry divisions were also undermanned and underequipped, the artillery lacked anti-tank brigades, communications remained antiquated, the airforce lacked modern aircraft, airfields and trained pilots, and air defence was disorganized and poorly armed. In the spring of 1941 the Soviet military was a gawky teenager made ungainly by a rapid growth spurt and desperate for some independence. On the eve of war, some 2.5 million men in 15 armies, and 20 out of 28 mechanized corps, were defending the frontier and organized into five fronts (approximately the same as the German army groups): the smallest was the Northern Front, commanded by Lieutenant-General M.M. Popov, which faced the Finns and the Germans in Norway; Colonel-General F.I. Kuznetsov’s Northwestern Front faced Army Group North in the Baltic states; Army Group Centre was confronted by General D.G. Pavlov’s Western Front; the Southwestern Front under Colonel-General M.P. Kirponos was opposite Army Group South, and the Southern Front, commanded by Major-General I. Tiulenev, was waiting opposite Romania.

This first strategic echelon was arranged in three shallow and incomplete defensive belts, which would also be expected to carry out local counterattacks against the advancing Germans. A further five armies were assembled on the critical obstacles of the Dnieper and Dvina rivers to form the second strategic echelon, which was to carry out the decisive, crushing counteroffensive and push into Germany. Whether the half-equipped, rigid and unwieldy mechanized corps were capable of sustained operations deep into the enemy rear was unlikely. However, the longer the Soviets offered resistance, the more they could draw on their expanding resources, which included some 14 million men with basic training ready to move into the line. Even so, informed observers gave the Soviets little hope of lasting long enough to bring these troops into action. The British Joint Intelligence Committee was convinced that Moscow would fall within six months, while its US equivalent expected a German victory within weeks.

As the Red Army dug in on the frontier during the spring of 1941, the Germans began their deployments towards them. Hitler’s preparations for Barbarossa were complicated by fighting around the Mediterranean in support of the Italians during the spring. Drawn into North Africa, Yugoslavia and then Greece, the Germans rounded off their successful sweep with an invasion of Crete. The diversion meant that the launch of Barbarossa had to be delayed until 22 June. It also added extra wear to vehicles, equipment and men, and pushed the offensive closer to the worsening autumn weather. The delay convinced Stalin that it was too late in the year for Hitler to attack. He also thought that Hitler would not consider taking on the might of the Soviet Union until his dispersed military machine had been brought together and was stronger. ‘We have a non-aggression pact with Germany,’ Stalin explained to a colleague. ‘Germany is up to her ears with the war in the West and I am certain that Hitler will not risk creating a second front by attacking the Soviet Union. Hitler is not such an idiot and understands that the Soviet Union is not Poland, not France, and not even England.’

Unwilling to face the awful truth that he had placed the Soviet Union in a supremely vulnerable position, Stalin rejected intelligence that strongly suggested an imminent German attack. A German Communist spy in Tokyo, Richard Sorge, confirmed his frequent warnings with an invasion date of 20 June. Meanwhile, Head of Soviet Military Intelligence Lieutenant-General Filip Golikov, fearful of providing reports that ran contrary to what Stalin wanted to hear (for several of his predecessors had been shot for their explicit warnings), reported at the end of March:

The majority of the intelligence reports which indicate the likelihood of war with the Soviet Union in spring 1941 emerge from Anglo-American sources, the immediate purpose of which is undoubtedly to seek the worsening of relations between the USSR and Germany.

Thus threats were deemed ‘imagined’ or ‘exaggerated’ and Golikov dismissed Sorge’s intelligence in a sentence: ‘We doubt the veracity of your information.’ Consequently, in a fit of remarkable optimism, Stalin chose to believe that the obvious German military build-up – together with more than 300 high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft sorties over Soviet territory – was an attempt by Hitler to extract more economic and political concessions out of him. Soviet passivity in the face of provocation led Goebbels to note in his diary that May: ‘Stalin and his people remain completely inactive. Like a rabbit confronted by a snake.’

Timoshenko and Zhukov made efforts to shake Stalin out of his stupor and mobilize, but to no effect. In mid-March they asked the General Secretary to authorize the call-up of reserve personnel ‘so as to update their military training in infantry divisions without delay’, but were told that ‘calling up reservists on such a scale might give the Germans an excuse to provoke war’. Undeterred, the two men continued to badger Stalin, whose patience reveals his considerable respect for the two soldiers. Timoshenko’s stock remained relatively high after his success in Finland and Stalin rated Zhukov as a battlefield commander, particularly after his success at Khalkin Gol. Dynamic and unconventional, ruthless and focused, former NCO Zhukov had supreme confidence in his own ability and excelled when put under pressure. By the end of the month, the tenacity shown by Timoshenko and Zhukov was partially rewarded when Stalin made a concession and gave permission for them to call up some 500,000 men for border military districts to augment infantry divisions, and 300,000 more were called up in early April – but their deployments would not be completed until 10 July. The military hierarchy continued to make discrete preparations for war, but on 14 June Timoshenko and Zhukov were again refused authorization for full mobilization. This time Stalin lost his cool; the pressure was beginning to tell, and after his Commissar for Defence had left the room he ranted, ‘It’s all Timoshenko’s work. He’s preparing for war. He ought to have been shot . . .’

By Saturday, 21 June, the longest day of the year, Soviet troops were enjoying the warm weather and looking forward to their day off. The Western Front headquarters were relaxed and General Pavlov enjoyed an evening at a Minsk theatre. Even when his head of intelligence sidled up to inform him of stories about an imminent German attack, Pavlov remained unperturbed, replied, ‘It can’t be true,’ and stayed in his seat. He received a full briefing later, in which it was explained that ‘considerable activity along the front line’ and intelligence from deserters pointed to a German attack ‘within hours’. The information came from Wehrmacht soldiers with Communist sympathies, including Sapper Alfred Liskow, who crossed the lines and told of a dawn crossing of the River Bug with ‘rafts, boats and pontoons’. Border guards reported hearing tank engines being started, vehicles moving and a flurry of activity by enemy troops, but Stalin remained unmoved and explained it as a deliberate German ploy to provoke the Soviet Union. Timoshenko, Zhukov and Lieutenant-General Nikolai Vatutin, the Deputy Head of the Planning Division, did not agree and immediately went to see the General Secretary. Finding him pale and ill at ease, the triumvirate implored him to put the armed forces on full alert. While still hanging on to the last worn strand of hope that Hitler was merely sabre rattling, he agreed. The resultant directive announced:

A surprise attack by the Germans . . . is possible during the course of 22–23 June 1941. The mission of our forces is to avoid provocative actions of any kind, which might produce major complications . . . Disperse all aircraft . . . and thoroughly camouflage them before dawn on 22 June 1941 . . . Bring all forces to a state of combat readiness.

Few formations received this warning due to the shambolic state of Soviet communications. Pavlov, meanwhile, took matters into his own hands and checked on the readiness of his troops. To his dismay he found that they were dispersed on exercises, required vital supplies and were hamstrung by a lack of transport.

He did not sleep that night but minutes after Stalin retired to bed, the first German shells exploded on Soviet positions.

At 0315 hours on 22 June 1941, a shattering German barrage targeted Red Army defences along the entire front. It was followed by an immense ground advance, which was closely supported by ground-attack aircraft. Other elements of the Luftwaffe dropped their bombs on Soviet cities and attacked enemy airfields, destroying 1,200 aircraft. The German spearheads plunged forward, cracking open the enemy’s defences. In certain sectors, however, there was no enemy to fight. In Army Group North’s 6th Panzer Division, for example, Colonel Erhard Raus’s 6th Motorized Infantry Brigade saw no enemy that morning and enjoyed ‘the beauties of the landscape’. Recognizing that their luck could not last, his leading battalion probed ahead, expecting the worst. At around 1300 hours, they contacted the enemy. ‘The first victim of the ambush,’ Raus explains, ‘was the company commander, who was driving at the head of his column. Before he even had time to shout an order, he was shot through the forehead by a Russian sniper from a distance of at least 100 metres.’ The desperate fire-fight that ensued was replicated along the line as the border guards fought for their lives and German units sought to exploit gaps. Moscow garnered any scrap of information they could from the confusion, but Captain Ivan Krylov was told by a fellow staff officer:

Everything is going well . . . The men have been ordered not to die before taking at least one German with them. ‘If you are wounded,’ the order says, ‘sham death, and when the Germans approach, kill one of them. Kill them with your rifle, with the bayonet, with your knife, tear their throats out with your teeth. Don’t die without leaving a dead German behind you.’

Such tenacity was not without its merits, but it could not stop the defenders from becoming thoroughly dislocated as their command and control was shattered – a process assisted by German Special Forces, which had infiltrated the Soviet rear to cut telephone lines, attack headquarters and seize key bridges. The Germans intercepted panicked Soviet transmissions – ‘We are being fired on; what shall we do?’ – followed by silence. Such was the psychological impact of the attack and the chaos that ensued that the defenders struggled to comprehend what was happening to them, let alone slow down or stop the Germans.

Announcing the invasion to the waking nation in a radio broadcast, Goebbels spoke Hitler’s words in a triumphant tone:

At this moment a march is taking place that, for its extent, compares with the greatest the world has ever seen. I have decided today to place the fate and future of the Reich and our people in the hands of our soldiers. May God aid us, especially in this fight.

Later that morning an ebullient Hitler proclaimed to colleagues, ‘Before three months have passed, we shall witness a collapse of Russia, the like of which has never been seen in history.’ Meanwhile, in Moscow Stalin was struggling to understand the unfolding situation. At 0715 hours he had published Directive No. 2 to the armed forces, announcing the German invasion and ordering them to ‘attack the enemy and destroy him in those regions where he has violated the border [and] mount aviation strikes on German territory to a depth of 100–150km [60–90 miles].’ By the evening, however, as the scale of the impending disaster became clearer, Directive No. 3 authorized a general counteroffensive ‘without regard for borders’. What followed was a gigantic clash, without restrictions, between two great nations. It would not end until one of them had been destroyed.

The Red Army threw itself at the Germans with nine mechanized corps seeking to bedevil the invaders as they fought through the first echelon’s weak defences during the first two days. The Soviets fought with fury but without finesse and were no match for their adversary. Incapable of dealing with a fast-moving enemy, their cumbersome tank brigades were undermined by poor intelligence, supply difficulties and a tactical naivety that led to their destruction. Communications between units, formations, arms and services quickly disintegrated. Relying more on insecure and inflexible field telephones rather than radios, commanders could not impose their will on the battle and were either forced into inaction or decisions based on unconfirmed reports. Speaking for the higher formations, Zhukov later wrote that ‘commanding generals and their staff still had no reliable communication with the army commanders. Our divisions and corps had to fight in isolation, without cooperation with the neighbouring troops and aviation, and without proper direction from above.’ The ensuing disorganization allowed the Germans to achieve the momentum that their armoured forces needed to break through. Blockages could be removed by the Luftwaffe but such was the call on its services that the ground forces usually made an attempt themselves first. Raus’s brigade, for example, came upon KV-1 heavy tanks, which initially seemed unstoppable. He later wrote:

One of the tanks drove straight for the [150mm] howitzer, which now delivered a direct hit to its frontal armour. A glare of fire and simultaneously a thunderclap of a bursting shell followed, and the tank stopped as if hit by lightning. ‘That’s the end of that,’ the gunners thought as they took a collective deep breath. ‘Yes, that fellow’s had enough,’ observed the section chief. Abruptly, their faces dropped in disbelief when someone exclaimed, ‘It’s moving again!’ . . . [It] crashed into the heavy gun as if it were nothing more than a toy, pressing it into the ground and crushing it with ease as if it were an everyday affair.

The situation was eventually controlled by the armour-piercing shells of the superb 88mm gun – a powerful and versatile flak weapon, which proved a first-class tank killer.

Despite the continued German advance, the Soviets did not crumble but they did suffer heavy losses in men and material (by dusk on 23 June, 6th Panzer Division had destroyed 125 Soviet tanks). A German staff officer summed up the situation when he wrote: ‘The Russian mass is no match for an army with modern equipment and superior leadership.’ The skirmishing that had been expected of the Germans did not materialize and Zhukov admits in his memoirs that he and his colleagues severely underestimated the initial power of the attack:

We did not foresee the large-scale surprise offensive . . . we did not envisage the nature of the blow in its entirety . . . to concentrate such huge numbers of armoured and motorised troops and, on the first day, to commit them to action in powerful compact groupings in all strategic directions with the aim of striking powerful wedging blows.

As Moscow struggled to get a grip on a situation that was rapidly developing into a national disaster, the world reflected on the implications of Hitler’s invasion. Prime Minister Winston Churchill offered Britain’s full support to the Soviet Union and broadcast to the nation:

No one has been a more consistent opponent of Communism than I have for the last 25 years . . . But all this fades away with the spectacle that is now unfolding . . . We have but one aim and one single, irrevocable purpose. We are resolved to destroy Hitler and every vestige of the Nazi regime. It follows, therefore, that we shall give whatever help we can to Russia and the Russian people . . . His invasion of Russia is no more than a prelude to an attempted invasion of the British Isles . . . The Russian danger is therefore our danger and the danger of the United States, just as the cause of any Russian fighting for his hearth and home is the cause of free men and free people in every quarter of the globe.

Yet despite Churchill’s laudable intentions, British politician Harold Nicolson wrote in his diary on 24 June: ‘80 per cent of the War Office experts think that Russia will be knocked out in ten days.’

Immune from grand strategy and concerns about anything much more than their immediate future were the troops at the front. Surging forward, ever farther from their loved ones, the Wehrmacht hoped and believed that the campaign would be a short one. In Army Group South, Eleventh Army infantryman Gottlob Bidermann was part of an anti-tank company that was armed with 12 37mm guns. From notes made in a small, leather-bound diary, he later recalled: ‘Everyone was confident that this war against the Soviet Union, like the conflict with France and Poland, would pass quickly.’ Since his 132nd Division was in reserve during the early stages, his memories of the first week of Barbarossa were dominated by images of recently finished battles. ‘[I was] struck by the lingering smell of smoke and ashes,’ he remembered, ‘and soon we could observe the large craters and scorched vehicles that depicted the handiwork of the German Stuka dive-bombers.’ Marching through a parched landscape, Bidermann’s first sight of the enemy did not fill him with fear:

The dusty road was lined with endless columns of Russian prisoners in ragged khaki-brown uniforms . . . [m]any of those without caps wore wisps of straw or rags tied to their close-cropped heads as protection against the burning sun, and some were barefooted and half-dressed, giving us an indication of how quickly our attacking forces had overrun their positions . . . They filed past us silently and with downcast eyes; occasionally several of them could be seen supporting another who appeared to be suffering from wounds, sickness, or exhaustion.

Such images are echoed by 20-year-old infantryman Herbert Henry, who testifies:

The sight of the line of retreat of their army, wrecked by our tanks and our stukas, is truly awful and shocking. Huge craters left by the Stuka bombs all along the edges of the road that had blown even the largest and heaviest of their tanks up in the air and swivelled them round . . . we’ve been marching for 25 kilometres past images of terrible destruction. About 200 smashed-up, burnt-out tanks turned upside down, guns, lorries, field kitchens, motor-cycles, anti-tank guns, a sea of weapons, helmets, items of equipment of all kinds, pianos and radios, filming vehicles, medical equipment, boxes of munitions and books, grenades, blankets, coats, knapsacks. In among them, corpses already turning black.

Bidermann and Henry were part of a well-oiled machine that drove the front forward remorselessly in a series of encirclements and thrusts. Punching forward towards Moscow, Army Group Centre made good progress against Pavlov’s Western Front, which found it difficult to break contact and withdraw to regroup and take up better defensive positions. Within days, Guderian’s Second Panzer Army and Hermann Hoth’s Third Panzer Army were creating a double envelopment around Minsk in an attempt to remove the Western Front from the Soviet order of battle. The Luftwaffe made short work of those units that pulled back in disorder, and regularly attacked any Soviet concentrations. Arriving in a non-descript village with a Red Army unit, war correspondent Vasily Grossman later noted:

[T]hree Junkers appeared. Bombs exploded. Screams. Red flames with white and black smoke. We pass the same village again in the evening. The people are wide-eyed, worn out. Women are carrying belongings. Chimneys have grown very tall, they are standing tall amid the ruins. And flowers – cornflowers and peonies – are flaunting themselves so peacefully.

He had already witnessed the impact of a raid on Gomel as the Luftwaffe sought to disrupt Soviet westward movement, and made some notes in his journal:

[H]owling bombs, fire, women . . . The strong smell of perfume – from a pharmacy hit in the bombardment – blocked out the stench of burning, just for a moment. The picture of burning Gomel in the eyes of a wounded cow.

Minsk was also heavily bombed as Army Group Centre surrounded it. ‘The whole city was in flames,’ Zhukov later wrote. ‘Thousands of peaceful inhabitants hurled their dying curses at the Nazi brutes.’ By the fifth day of the German offensive Pavlov was reporting to Moscow that he was powerless to stop the German tanks from creating their encirclement. Although of very limited military value, the Western Front was told to do all that it could to slow Bock’s advance and was ordered to defend the city.

Even as Pavlov pondered his options, on 26 June Zhukov, Timoshenko and Vatutin were meeting with Stalin to discuss plans to defend Moscow. They were all tired and Stalin was irritable. Leading them to the table in his office on which lay a marked map, the General Secretary growled, ‘Put your heads together and tell me what can be done in this situation.’ Their proposal was quickly accepted: ‘building up a defence in depth on the approaches to Moscow, continuously harrying the enemy and checking his advance on one of the lines of defence, then organizing a counteroffensive, by bringing up for this purpose troops from the Far East together with new formations.’

As the Soviet hierarchy moved to put this plan into action, on 30 June Bock’s panzers completed their encirclement of Minsk and isolated the 10th, 3rd, 4th and 13th Armies. Guderian called it ‘the first great victory of the campaign’. As the plodding infantry closed up to eliminate the pocket that had been created, the beleaguered Soviets were gradually overwhelmed. Some escaped through the porous German clinch to regroup and then join troops trying to stop the armoured spearheads from reaching the Dnieper in early July, but these attempts were doomed to failure. On 10 July, the day after resistance at Minsk had been crushed, Guderian had already begun his crossing of the Dnieper. In less than three weeks, Bock’s Army Group Centre had advanced 360 miles and cost the Soviets 417,790 casualties, 4,799 tanks, 9,427 guns and mortars and 1,777 combat aircraft. Pavlov – a medal-festooned Hero of the Soviet Union – was executed along with eight other senior officers for ‘lack of resolve, panic-mongering, disgraceful cowardice . . . and fleeing in terror in the face of an impudent enemy’. The regime had ‘gripped’ the situation in the only way that it knew how. Failure was met by death either at the hands of the Germans or the NKVD. It was now up to Pavlov’s replacement, Timoshenko, to stem the German tide west of Moscow, the city Stalin referred to as ‘the beating heart of the Soviet Union’.

The defence of the capital may have been regarded by the Soviets as critical to their survival, but the Germans were also planning to overrun Leningrad and the Ukraine. Army Group North’s armour advanced to a depth of 60 miles on the first day of the campaign and was far too strong for Kuznetsov’s Northwestem Front. Having raced through Lithuania, elements of Colonel-General Erich Hoepner’s Fourth Panzer Army had pushed 270 miles to the Western Dvina by 26 June. The river was crossed on 2 July, after the infantry had caught up, and Leeb then focused on smashing the defences that Popov’s Northern Front had hastily erected to protect Leningrad. In an attempt to stop the German juggernaut, Stalin despatched Nikolai Vatutin to provide Kuznetsov with trusted support. On his arrival from Moscow, Vatutin immediately asked for the Front’s losses so far and was horrified to learn that they amounted to 90,000 men, 1000 tanks, 4000 guns and mortars and over 1000 combat aircraft. Turning to the dishevelled Front commander, he said, ‘Leningrad must not fall. We must do everything in our power to defend the approaches to the city – even if it leads to the destruction of your formation.’

Army Groups Centre and North had made an excellent start to the campaign, but Army Group South had progressed less well. Advancing along the worst roads and facing the strongest Soviet formations in defence of the resource-laden Ukraine, Rundstedt’s formation ran headlong into the Southwestern and Southern Fronts. The main attack emanated from southern Poland and, led by Colonel-General Ewald von Kleist’s First Panzer Army, headed towards Kiev while 200 miles away a subsidiary attack sought to clear the southern Ukraine and the Black Sea coast. For the first two days of the offensive Rundstedt had little difficulty in overrunning the border defences, but then Kirponos – with Zhukov temporarily at his side, to ensure that he was resolute and bold – ordered armoured counterattacks. The huge armoured battle that developed involved more than 2000 tanks ranging across a 42 mile front. It failed to stop the First Panzer Army but stretched German resources, undermined Kleist’s momentum and tested his nerve. By 30 June, Rundstedt’s armour had reached Lvov and was closing in on Rovno. The Southwestern Front, having lost more than 2,600 tanks since 22 June, was struggling to extract itself from a rapidly deteriorating situation and feared encirclement. Colonel I.I. Fedyuninsky, commanding 15th Rifle Corps of 5th Army, has testified:

Sometimes bottlenecks were formed by troops, artillery, motor vehicles and field kitchens, and then the Nazi planes had the time of their life . . . Often our troops could not dig in, simply because they did not have the simplest implements. Occasionally trenches had to be dug with helmets, since there were no spades.

Farther south, Tiulenev’s Southern Front was also being pushed back and struggled to stay in contact with the Southwestern Front’s left flank as Army Group South’s secondary thrust sought to break the two apart. Retreat, again, was inevitable and was punishing for the Soviets. Gottlob Bidermann’s formation remained the reserve but he continued to slog forward in ferocious heat and thunderstorms through ‘an endless open space with only occasional clusters of sparse trees stretching to the horizon’. He wrote:

For days great numbers of destroyed Russian tanks lined our path, and capsized prime movers with limbered field guns were scattered along the roadsides. In the fields one could see numerous abandoned Russian artillery positions that appeared to be intact, indicating how quickly our offensive had overtaken the Soviet defenders . . . The graves of German and Russian soldiers were now found to be close together.

The situation did nothing to dispel Bidermann’s belief that the Red Army was no match for the Wehrmacht and he remained concerned that his unit would not see action ‘before the inevitable surrender of the Soviet Union’.

The Soviets had been dealt a severe blow in the ‘Battle of the Frontiers’. The invaders had pushed over 350 miles into their territory and inflicted on them some 172,323 casualties with the loss of 4,381 tanks, 5,806 guns and mortars and 1,218 combat aircraft. The German High Command felt confident that the whole business could be brought to a victorious conclusion quickly. Franz Halder wrote in his diary: ‘The objective to shatter the bulk of the Russian Army this [western] side of the Dvina and Dnieper has been accomplished . . . It is thus probably no overstatement to say that the Russian Campaign has been won in the space of two weeks.’ Hitler was so optimistic that he ordered massive new armaments programmes for the airforce and the navy in preparation to defeat the British and take the war to the United States. Yet those who were willing to strip away the euphoria surrounding the first weeks of success recognized that there was still plenty of fight in the Red Army. Many front-line commanders reported stiffening resistance and evidence of stretched lines of communication. But could the Red Army withstand the continued onslaught long enough to take advantage of German overstretch?

By the end of June, Stalin was physically and mentally drained. He had given his all to managing the crisis, and had done so, as a colleague later wrote, ‘displaying confidence and calmness and demonstrating great industriousness’. Nevertheless, the General Secretary had been humiliated by Hitler’s invasion. Less territory had been lost by Tsar Nicholas II during the Great War prior to the revolution, and recognizing this Stalin admitted, ‘Lenin founded our state and we’ve fucked it up.’ In what seemed like a fit of despondency, Stalin retreated to his Kuntsevo dacha on 29 June and suddenly stopped leading. Contrary to impressions, though, Stalin had not given up hope and had already directed organizational changes that, he believed, would streamline the Soviet response and help harness the nation’s strengths. Before continuing the work, however, he wanted to test the foundations of his leadership. By taking himself away from the Kremlin, he paused not only to draw breath but also to draw political enemies out into the open. Yet rather than attempting to seize power on 30 June, Molotov, the only credible alternative to Stalin, led a delegation to the dacha. He recalled: ‘Stalin was in a very agitated state. He didn’t curse, but he wasn’t quite himself. I wouldn’t say that he had lost his head. He suffered, but didn’t show any signs of this.’ Molotov explained that the Politburo wanted Stalin to take up the reins of power once more and head a State Committee for Defence (GKO), a body with total power to conduct the war as it saw fit. The GKO would direct the activities of government departments and the General Staff, which concerned itself with strategy, as well as the Stavka (the Supreme High Command of the Soviet Armed Forces), which Stalin had activated on 23 June with responsibility to prepare and conduct military campaigns, coordinate operations and organize forces.

Stalin replied to Molotov’s request with a modesty that was not out of character: ‘Can I lead the country to final victory?’ Kliment Voroshilov, the Deputy Premier, replied, ‘There is none more worthy.’ Stalin shifted uneasily, looked into the eyes of the waiting men, and finally agreed to take up the position. At that moment he became titular Supreme Commander of the Soviet Union and days later added the role of People’s Commissariat of Defence to his already extensive portfolio of appointments. Stalin had cleverly used a national emergency to complete his quest to attain ultimate authority. By 10 July 1941, Stalin dominated the Party and executive, controlled the armed forces and directed all strategic decision making.

Stalin threw himself into work with renewed vigour and immediately took steps to ensure that the Soviet Union could sustain its war effort over the coming months and years. Using all of the organizational skills that he had developed in clawing his way to power, Stalin oversaw the raising of reserves, the evacuation of Moscow and measures to ensure that the Soviet Union’s manufacturing infrastructure was kept out of Hitler’s reach. He was absolutely insistent that the route to victory lay in out-producing Germany, and as a consequence some 1,523 factories had been moved more than 1000 miles east of Moscow by November. This forward thinking, along with a ‘scorched earth’ policy of destroying anything of use in the path of the rampaging enemy, provided the foundations for the nation’s long-term resistance to the Germans. Indeed, Zhukov later declared, ‘The heroic feat of evacuation and restoration of industrial capacity during the war, and the Party’s colossal organizational work it involved, meant as much for the country’s destiny as the greatest battles of the war.’

Stalin knew that this work would be for nothing if the fighting front collapsed, and along with spending considerable time overseeing the development of plans to thwart the Wehrmacht's march eastwards, he also attended to military discipline. He was concerned at the high desertion rates across the front in June (5000 men were caught running from one bloody Southwestern Front battle) and reports of self-inflicted wounds, which together not only led to denuded defences but also eroded the morale of those who were left to do the fighting. Wanting to ensure that each and every soldier felt the Party’s hand on his shoulder, on 16 July Stalin reintroduced ‘dual command’, which required military commanders to work in harness with a political officer or commissar. Those caught with self-inflicted wounds were summarily executed by members of the NKVD Special Department. Deserters faced a three-man military tribunal, which could order the death sentence. Meanwhile, Levrentiy Beria, head of the NKVD, was ordered by Stalin to remove unreliable elements from military units and to arrest those spreading rumours and indulging in defeatist rhetoric. The result was another bloody, merciless purge in which nearly one million Red Army personnel were condemned by military tribunals and many more were shot on the spot without trial.

To stiffen further the resolve of the troops, Order No. 270 condemned all those who surrendered or were captured as ‘traitors to the motherland’, and branded any officer who retreated or gave himself up as ‘a malicious deserter’, liable to be shot in the field and have his family arrested. One of the first victims of this Order was Stalin’s own son, Yakov, whose capture in early July led to his wife spending two years in a labour camp. Stalin did not intervene in the matter and refused to exchange his son for a high-ranking German prisoner. Yakov was eventually shot, having deliberately walked into the perimeter zone at his prisoner-of-war camp.

Stalin’s ‘terror’ and harsh policies did little to deal with the cause of desertion and self-inflicted wounds. Morale was often very poor and it was not uncommon to find soldiers underweight, since their diets did not provide the calories that they needed. Breakfast was thick soup, lunch was buckwheat kasha, tea and bread, followed by more soup and tea in the evening. Sometimes they received nothing at all for days on end. One soldier wrote home: ‘We’re living in dugouts in the woods. We sleep on straw, like cattle. They feed us very badly – twice a day, and even then not what we need. We get five spoonfuls of soup in the morning . . . we’re hungry all day.’ Gabriel Temkin observed a Red Army unit in his village: ‘Some in trucks, many on foot, their outdated rifles hanging loosely over their shoulders. Their uniforms worn out, covered with dust, not a smile on their mostly despondent, emaciated faces with sunken cheeks.’ These men did not look as though they were physically capable of giving battle and many were mentally fragile. Poor preparation and low motivation – many did not support the regime and half were non-Russian – undermined their capabilities while ‘suicidal orders’ and naive tactics often led to heavy casualties. The skinny Soviet infantry threw themselves at heavily armed enemy formations with fixed bayonets and cries of ‘Hoorah!’ but often without air or artillery support. They attacked in waves, which the Germans cut down with automatic fire, mortars and artillery until there were no more, leaving heaps of dead on the battlefield.

The truly horrific losses at the front were glossed over by the regime, which managed and manipulated the information released to the population. Stalin did not want the Soviet people to recoil in horror from the war, for as poet David Samoilov said, ‘We were all expecting war. But we were not expecting that war.’ Stalin wanted them to embrace the struggle with passion and resilience. Propaganda was therefore written by skilled writers, overseen by the Sovinformbiro (Soviet Information Bureau), which had been established in the first days of the war to ‘bring into the limelight international events, military developments, and day-to-day life through printed and broadcast media’. Journalists and stories were carefully controlled by censors, and trusted officials inspected copy for ideological mistakes. Thrice weekly press conferences were held by the Deputy Foreign Commissar Solomon Lozovsky, who was also the Deputy Chief of the Sovinformbiro. His tone was always optimistic, lost territory was only temporary and major disasters were not mentioned at all. Front-line troops had their own press. The most popular was The Red Star, for which Vasily Grossman wrote. It was often read aloud to the troops, who were also shown carefully constructed newsreel re-enaction of their battles.

Radio was a great source of information, and millions listened to broadcasts by anchorman Yuri Levitan, who always started with the words ‘This is the Soviet Information Bureau . . .’ and provided considerable detail of heroic Soviet actions and successes. However, listeners soon learned that phrases such as ‘fighting in the Minsk direction’ meant that the city had already been lost, and that ‘heavy defensive battles against superior enemy forces’ meant a full and disorderly retreat.

On 3 July, radio listeners heard Stalin addressing the nation for the first time in the war. Erskine Caldwell, an American living in Moscow, wrote of the event:

At 6.30 a.m. practically every person in the city was within earshot of a radio, either home set or street loudspeaker. Red Square and the surrounding plazas, usually partially deserted at that hour, were filled with crowds. When Stalin’s speech began, his words resounded from all directions, indicating that amplifiers were carrying the message to every nook and cranny of the city.

Delivered in an unusually clear, calm voice, Stalin spoke of Germany as an ‘unprovoked aggressor . . . [a] vicious and perfidious enemy’. However, in calling for the country to defeat the invader, he did not try to tap into the nation’s revolutionary zeal but, just like Molotov’s announcement of war on 22 June, he called for a ‘patriotic war . . . a war of the entire Soviet people’ in an attempt to reach out to a wider constituency. Despite the excesses of his regime, Stalin’s patriotic war demanded that the Soviet Union unite against a deadly common enemy. He ended his address with the words, ‘Comrades! Our arrogant foe will soon discover that our forces are beyond number . . . Forward – to victory!’

Captain Ivan Krylov has said, ‘the tone of [the speech] surprised me . . . It had occurred to me that this new tone was due to exceptional danger. He was afraid . . . He was doubtful of the attitude of the people in face of the German attack; he was afraid of a revolt against the regime.’ It was, according to journalist Alexander Werth, based in Moscow to report for the Sunday Times, an ‘extraordinary’ performance, and he later wrote in his history of the war that it was essential to a ‘frightened and bewildered people’ and meant that, after all the ‘artificial adulation’, they now ‘felt that they had a leader to look to’. Erskine Caldwell agreed and noted:

As an observer, I had the feeling that this announcement immediately brought about the beginning of a new era in Soviet life. The people have heard for the first time since the war began a fighting speech by their leader. As a Russian said to me, you may be sure that from this moment a grapple with death has begun . . . I would not be surprised if the entire population of Moscow suddenly besieged the military offices for permission to move en masse to the front.

During the first days of the war, a flood of Soviet men had poured into hastily established recruiting stations to volunteer for service in a rush of patriotism, panic, anger and duty. In Moscow, 3,500 men presented themselves for service in the first 36 hours while in the Kursk province some 7,200 people applied for front-line duty in the first month. One man from the city of Kursk told a crowd: ‘I lived through German rule in the Ukraine in 1918 and 1919. We will not work for landlords and noblemen. We’ll drive that bloodstained Hitler out bag and baggage. I declare myself mobilized and ask to be sent to the front to destroy the German bandits.’ Few volunteers had any idea of what they were signing up for. Life in the military was brutal. The average front-line tour of duty for an infantryman was just three weeks before he was seriously wounded or killed. The regime had to ensure that they had bodies to replace the fallen and it did not take the Soviet propaganda machine long before it was churning out posters and literature to remind the population of their ‘patriotic duty’. Alexander Werth reported from the capital:

Posters on the wall were eagerly read, and there were certainly plenty of posters: a Russian tank crushing a giant crab with a Hitler moustache, a Red soldier ramming his bayonet down the throat of a giant Hitler-faced rat – ‘Razdavit fascistskuyu gadinu’, it said: ‘Crush the Fascist vermin’; appeals to women – ‘Women, go and work on the collective farms, replace the men now in the Army!’ . . . Pravda or Izvestia with the full text of Stalin’s speech were stuck up, and everywhere crowds of people were rereading it.

Women did take the place of men on the land and in factories – by the end of the year they made up 41 per cent of the labour force – but 800,000 were also accepted into the military as nurses and laundresses, and eventually as snipers, tank crews, gunners, infanteers and naval crew. It was not unusual for a small group of women to serve together in a section or a crew. In fact, there was a policy of keeping groups of volunteers together because it was deemed advantageous for morale. The result was ‘The Sportsmen’s Company’, ‘The Writers’ Company’, ‘The Musicians’ Company’ and the like. During July author Konstantin Simonov came across one such unit filled with men aged between 40 and 50 years old in tatty tunics.

I remember that they produced a gloomy impression on me at the time . . . [they] were thrown in to plug the gap, because something – anything – had to be thrown in, at whatever the price, to preserve the front, which the reserve armies were preparing further to the East, nearer to Moscow, from being shattered to pieces . . . I thought: do we really have no other reserves besides these volunteers, dressed anyhow and barely armed?

There were reservists, of which 5.3 million were mobilized in the last week of June, but with the age of conscription soon lowered to 18 years and the volunteering campaign growing in scope, it was evident that everybody had a part to play in the rapidly developing total war. This included groups of partisans made up of civilians and those troops who had become separated from their units. Scant planning had been made for irregular warfare by the outbreak of war, but its potential was soon recognized by Moscow, and in July Stalin said, ‘There must be diversionist groups for fighting enemy units. In the occupied areas intolerable conditions must be created for the enemy and his accomplices.’ Within a year, an estimated 90,000 partisans were operating behind enemy lines. Many were directed by special NKVD units sent by Moscow for the purpose. These units were not only a means of unhinging the enemy through acts of sabotage, ambushes and attacks on their lines of communication, but also became the face of the Party in occupied territory. One German infantry officer, Karl Hertzog, recalls:

We feared the partisans. They were ruthless and difficult to track down. We expended considerable time, energy and resources trying to locate them, but we rarely did. On one occasion I led a patrol into a known partisan stronghold and just escaped with my life. My platoon was slaughtered. Ten were killed on the spot, 15 were taken prisoner and the remainder – myself included – managed to escape. Three days later we found the dismembered corpses of those men who had been captured by the side of the road.

The stoicism of the Soviet troops and the viciousness of the partisan action were based in a complicated mixture of factors, but chief among them was the defence of their homeland. There was a widely held belief that the invaders would take away the little that they had. Gottlob Bidermann has said:

The individual soldiers of the Red Army evolved into fighters distinctly different from soldiers we had first encountered. The mentality of the soldier changed from one of apathy and indifference to that of a patriot. The idea of belonging to an élite army that was alone saving the world from Fascism was being instilled, and a sense of pride evolved that had long been absent from the ranks of the Soviet armed forces.

Indeed, an elderly Tsarist general told Heinz Guderian:

If only you had come twenty years ago we should have welcomed you with open arms. But now it’s too late. We were just beginning to get on our feet and now you arrive and throw us back twenty years so that we will have to start from the beginning all over again. Now we are fighting for Russia and in that cause we are all united.

The population’s developing affinity with the cause was given substance by the Germans’ often contemptible, ideologically motivated treatment of prisoners and civilians. The ‘cleansing’ of captured territories was primarily carried out by four SS Einsatzgruppen (Special Operation Units), which acted as paramilitary death squads. Jews and those elements deemed to be hostile to German interests were either arrested and used as slave-labour – the first of seven million who arrived from occupied territories – or were executed. The genocide was carried out not just by the SS. Before the invasion the army high command had issued a formal instruction, the ‘Commissar Order’, that captured ‘political leaders and commissars’ were to be shot on the spot. Moreover, Wehrmacht soldiers were expected to ‘cooperate’ in Hitler’s stated ambition for the Soviet Union – ‘Occupy it, administer it, exploit it’ – and had been legally exempted from a whole catalogue of crimes. Some units and some soldiers had no compunction in crossing the moral line and complying with Hitler’s most repugnant demands, which were treated as routine military operations. Others did it because they were weak and some conformed for an easy life. Mass executions of civilians followed the Wehrmacht’s arrival in a town or village. The observer of one such act in Lotoshino told Alexander Werth:

The first day the Germans came . . . they hanged eight people in the main street, among them a hospital nurse and a teacher. The teacher’s body was left hanging there for eight days. They had called for the people to attend the execution, but few went.

The Wehrmacht were followed by the Reich Commissars, who administered the occupation with a heavy hand. Alana Molodin says, ‘It was a difficult time. I was twelve years old and made to work for the Nazis. I became a servant at the administrator’s office and counted myself as lucky . . . Friends were raped, beaten and disappeared. I was regularly hit. I witnessed one elderly lady shot as she shuffled in front of an impatient German’s car.’ It also became common for Soviet prisoners to be executed. Hertzog said that this first occurred due to ‘a lack of resources to deal with the hundreds of men that we captured’. The Germans had not made adequate provision for the taking of prisoners and their extermination relieved units of their responsibilities for them. A German soldier testifies:

Once a soldier had killed in combat and had friends die at their side, it was not so very difficult for some to shoot dead unarmed prisoners. It is not an excuse, but we were barbarised by war. Moral boundaries became blurred and only the best officers made them clear. I am ashamed to say that I was the member of a unit that carried out atrocities. But at the time we saw it as our job. We did not think about it. We saw ourselves as dead men walking in any case.

By 8 September the murder of Red Army troops was given legitimacy by an OKH decree, which stated that Soviet prisoners of war had ‘forfeited all rights’. The results were horrendous. One civilian recalled:

[T]he enemy locked captured Red Army men in a four-storey building surrounded by barbed wire. At midnight the Germans set fire to it. When the Red Army soldiers started jumping from the windows the Germans fired at them. About seventy people were shot and many burned to death.

Those who were not executed faced an awful ordeal in filthy compounds surrounded by barbed wire, without shelter, food, water or warm clothing. Some were killed at the whim of their guards; most suffered beatings and were left to die in squalor.

German excesses were not without their negative consequences. A German intelligence officer argued in a report about the root of Soviet fighting spirit: ‘It is no longer because of lectures from the politruks, but out of his own personal convictions that the Soviet soldier has come to expect an agonizing life or death if he falls captive.’ Heinz Guderian concurred. Describing a scene near Smolensk, he wrote:

A significant indication of the attitude of the civilian population is provided by the fact that women came out from their villages on to the very battlefield bringing wooden platters of bread and butter and eggs and, in my case at least, refused to let me move on before I had eaten. Unfortunately this friendly attitude towards the Germans lasted only so long as the more benevolent military administration was in control. The so-called ‘Reich commissars’ soon managed to alienate all sympathy from the Germans and thus prepare the ground for all the horrors of partisan warfare.

Although the Soviet regime put in place a number of measures to ensure that the Red Army soldier fought to the last round, increasingly it was German behaviour that proved the greater motivator. Far from tapping the significant anti-Stalin sentiment present in the Soviet Union in 1941, the invaders legitimized Stalin’s rule in a way that he could never do. A Soviet officer told Werth:

This is a very grim war. And you cannot imagine the hatred the Germans have stirred up amongst our people. We are easy-going, good-natured people, you know: but I assure you, they have turned our people into spiteful mujiks. Zlyie mujiki – that’s what we’ve got in the Red Army now, men thirsting for revenge. We officers sometimes have a job in keeping our soldiers from killing German prisoners; I know they want to do it, especially when they see some of these arrogant, fanatical Nazi swine. I have never known such hatred before. And there’s good reason for it . . . I cannot help thinking of my wife and own ten-year-old daughter in Kharkov.

Vasily Grossman found a locket on a dead Soviet soldier, Lieutenant Miroshnikov, with a note inside:

If someone is brave enough to remove the contents of this locket, could they send this to the following address . . . ‘My sons, I am in another world now. Join me here, but first you must take revenge on the enemy for my blood. Forward to victory, and you, friends, too, for our Motherland, for glorious Stalin’s deeds.’

Death and destruction continued across the front during July as the Wehrmacht progressed towards Leningrad, Moscow and Rostov. While all three German army groups posed threats, it was Army Group Centre’s advance towards the capital that caused Stalin most concern. Bock’s formation grappled with the remnants of six Soviet armies while an army from the reserve was deployed behind them at Smolensk – 230 miles west of the capital – and a further two armies defended Moscow itself. Unable to do more than temporarily slow the onslaught, the Soviet formations fell back and by the middle of the month the German armour looked ready to encircle Smolensk. Despite the danger to the withdrawing forces posed by Bock’s panzers, the fractured armies were ordered to defend the city for as long as possible in order to provide Moscow with time to prepare its defences. A tremendous battle followed, which caused Guderian great difficulty in sustaining his momentum as casualties mounted and his logistics buckled. The situation became so acute that the commander of the 18th Motorized Division, whose tired troops were fighting through intense heat and in choking dust, thought that a halt was required ‘if we do not intend to win ourselves to death’. But the Second Panzer Army pressed on regardless while the infantry raced to catch them up. One of those trudging his way eastwards was 30-year-old German Signals NCO Helmuth Pabst. Footsore and sunburned, having marched 780 miles, Pabst wrote in his diary on 16 July that his ‘knees were shaking’ with fatigue.

Army Group Centre was visibly tiring but Hitler was entirely confident that it was in a prime position to take its goals, and ordered the Luftwaffe to begin bombing Moscow. The first raid took place during the night of 21 July and was met by a tremendous anti-aircraft barrage, ‘shrapnel from the anti-aircraft shells clattering down on to the streets like a hailstorm; and dozens of searchlights lighting the sky’. Three rings of anti-aircraft defences surrounded the city and, during that first raid, just a dozen of the 200 German bombers managed to break through. Undeterred, similar operations followed as Hitler endeavoured to undermine Soviet defensive arrangements before launching a ground attack on the city.

Bock was on the point of taking Smolensk, although weakening, but Berlin did not take the option of downgrading the attacks on Leningrad and the Ukraine to reinforce Army Group Centre – quite the opposite. With a firm flank established from Velikie Luki 120 miles north to Lake Illmen, in early July Army Group North’s Eighteenth and Fourth Panzer Armies struck out from the Western Dvina for Leningrad. Leeb’s men, issued with obsolete 1:300,000 maps, immediately found the going tough with well-set defences situated on difficult ground. Reflecting on the 6th Panzer Division’s progress, Erhard Raus has written:

[T]he enemy offered stubborn and skilful resistance in the woods and thickets, time and again launching counterblows supported by tanks . . . [T]he road suddenly changed into marshland of the worst kind. Tanks and guns bogged down . . . Progress became increasingly difficult . . . [T]he first moor could only be traversed after hours of backbreaking work by every officer and man, tormented by swarms of mosquitoes as they employed tree trunks, boughs, planks, and the last available fascine mats to create a barely passable route.

Nevertheless, Leeb’s unremitting pressure on the Soviet defences began to pay dividends and by 14 July the tenacious Army Group North’s persistent panzers reached the River Luga, just 80 miles south of Leningrad. Here some torrid defence by the Northern Front forced the tired German spearhead to stall for several days while they waited for the infantry, who were far to the rear, fully committed in clearing operations. Leeb faced a dilemma. His stretched lines of communication and the difficult terrain were causing shortages and undermining the momentum of his attack, and with three defensive belts protecting Leningrad, he needed all the power he could muster to break through. These obstacles had been constructed under the orders of Marshal K.E. Voroshilov, commander of the Northwestern Direction, one of three short-lived Soviet strategic commands that had been formed on 10 July for greater control and coordination of resources. His orders were simple: defenders were to ‘fight to the last round and the last drop of blood’ to prevent Hitler from securing Leningrad, the former capital and the birthplace of Bolshevism. Some valuable factories were located in the city, and from Leningrad the Germans could swing around to approach Moscow from the north. Voroshilov demanded, therefore, that the city be held ‘at all costs’.

As Leeb considered his options and reported to Berlin that he was facing ‘considerable obstacles to his future offensive plans’, Hitler urged Army Group South onwards into the Ukraine against the Southwestern and Southern Fronts. By 9 July, Rundstedt’s First Panzer Army, heading for Kiev, was still 60 to 120 miles short of the Dnieper. The Sixth Army lagged over a week behind and the Seventeenth Army was making even slower progress towards the Crimea. Rundstedt spoke to Hitler on 15 July and blamed his difficulties on ‘atrocious roads, intolerable heat and unexpectedly heavy enemy resistance’.

Gottlob Bidermann fought his first battle during this period. At the collective farm of Klein-Kargarlyk, his unit came under heavy fire as they worked to clear the position: ‘The incoming rounds shook the earth beneath us, and only with great effort could we hear the shouted commands above the explosions.’ An attack forced the enemy out into the fields, where they were immediately targeted. Bidermann recalled:

[O]ur forward machine-gun crews fired their MG-34s while standing on the waist-high wheat, each barrel resting across the shoulder of a crewman in order to maintain a clear field of fire. A number of Russians were struck by the bursts of machine-gun fire and tumbled to the earth, disappearing among the wheat stalks.

Having taken the objective, Bidermann and his colleagues rested – an advance of eight miles had taken six hours – and prepared for their next attack ‘in an endless land, where unbroken fields stretched to the horizon before us from sunrise to sunset. I wondered how many more . . . battles lay ahead of us during our march away from the setting sun.’ There was a great deal more fighting to do, and Rundstedt’s formation was struggling to keep up with its campaign timetable.

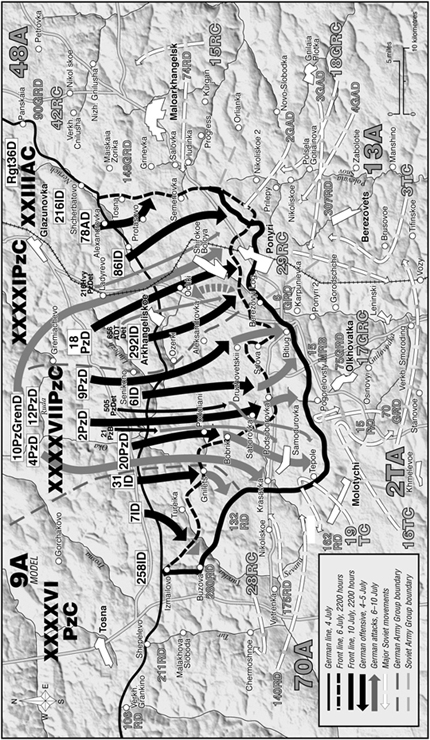

On 19 July, with Army Group North on the Luga, Army Group Centre in the process of completing the encirclement of Smolensk, and Army Group South still short of the Dnieper, Führer Directive No. 33 was published. In it Hitler announced: ‘The objective of future operations should be to prevent the escape of large enemy forces into the depths of Russian territory and to annihilate them.’ Bock was to continue his push on Moscow but with infantry alone. His Third Panzer Army was to assist Leeb’s assault on Leningrad and his Second Panzer Army was to drive south, linking up with Rundstedt’s Army Group South to complete a massive encirclement in the northern Ukraine. The attack on Moscow was effectively postponed as these ‘diversions’ sought to link up the front and give Army Group Centre an opportunity to consolidate around Smolensk. Although the pincers of Army Group Centre’s panzer armies met successfully east of Smolensk on 27 July, trapping 700,000 defenders, the success was marred by logistic turmoil and the strongest Soviet counterattacks to date. Moreover, 200,000 of those initially surrounded had managed to break out of their encirclement before the arrival of the German infantry.

Meanwhile, stubborn Soviet resistance against Army Groups North and South had raised questions in Hitler’s mind about whether it was prudent to charge on to Moscow while Leningrad and the Ukraine remained in enemy hands. The aim had never been to break Soviet will by taking Moscow, but to destroy the Red Army before advancing that far. As such, Berlin had never placed a great emphasis on the capture of the Soviet capital. On the eve of Barbarossa the General Staff had argued: ‘The occupation and destruction of Moscow will cripple the military, political and economic leadership as well as much of the basis of Soviet power. But it will not decide the war.’

The Germans were poorly placed to continue the advances to all three Army Group objectives. By the third week of July, although they had destroyed more than half of the Soviet order of battle, Soviet reserve and volunteer armies were being activated, over half of the German armour had been lost or was unserviceable, 40 per cent of all soft-skinned vehicles had been destroyed and lines of communication were overstretched, leading to shortages of critical supplies. The problems inherent in an operation that had multiple and competing strategic aims, and rested on inadequate campaign planning, short-term strategic preparation and a lack of resources, were now clearly visible. Hitler looked to the skill and flexibility of the Wehrmacht to overcome them.

In the wake of the Smolensk encirclement, Heinz Guderian was appalled to learn, at an Army Group conference, that his armour was being diverted away from Moscow. His anger remains palpable in the pages of his memoir that deal with the event. He wrote:

This meant that my Panzer [Army] would be swung round and would be advancing in a south-westerly direction, that is to say towards Germany . . . All the officers who took part in this conference were of the opinion that . . . these manoeuvres on our part simply gave the Russians time to set up new formations and to use their inexhaustible man-power for the creation of fresh lines in the rear area: even more important, we were sure that this strategy would not result in the urgently necessary, rapid conclusion of the campaign.

Führer Directive No. 34, published on 30 July, postponed the armoured diversions due to ‘the appearance of a large enemy force before the front, the supply situation, and the necessity of giving the Second and Third Panzer [Armies] 10 days to restore and refill their formations’. However, there were some changes to the plan for rather than continuing its attack towards Moscow with infantry alone, the tired and vulnerable Army Group Centre was to ‘go on the defence’ and protect Smolensk.

As Guderian’s Second Panzer Army made its preparations to link up with Army Group South, Rundstedt moved his Sixth Army towards Kiev. On 3 August meanwhile, Kleist’s panzers completed the encirclement of 20 divisions from 6th, 12th and 18th Armies around Uman, south of Kiev. They captured 107,000 officers and men, including the two army commanders, four corps commanders, 11 division commanders, 286 tanks and 953 guns. Two corps commanders and six division commanders perished. By this time, the Second Panzer Army had left Army Group Centre and begun its diversion to create the Kiev encirclement. Zhukov had anticipated this move, having blocked Army Group Centre’s route to Moscow with the new Central Front and given notice for a withdrawal: ‘The South-Western Front must be withdrawn in its entirety beyond the Dnieper . . . Kiev will have to be surrendered.’ Stalin disagreed, replaced Zhukov as Chief of the General Staff with Boris Shaposhnikov on 30 July, and sent him to command the newly activated Reserve Front. This Front was to attack Army Group Centre south of Smolensk at Yelnya, less than 200 miles from Moscow. Stalin’s decision to sack Zhukov had as much to do with his need for an experienced and reliable man to undertake operations to stall Bock’s advance as it had with his anger at the general’s decision to abandon Kiev.

By 6 August, Guderian was successfully smashing his way through the Soviet formations, which Stalin had relied upon to hold him. Damage was being inflicted on the Second Panzer Army, but not enough to thwart its progress. Telegraphing the Supreme Commander, Zhukov stated that the enemy was ‘throwing all of his shock, mobile and tank units against the Central, Southwestern and Southern Fronts, while defending actively against the Western and Reserve Fronts’. Time was running out for the Red Army in the Ukraine. Over the next two weeks, Guderian continued to chew his way forward and forced Moscow to take a decision about what to do next. On 21 August, at a critical Council of War, an exhausted Shaposhnikov recommended ‘a withdrawal towards Kiev’ and beyond to various lines of defence covered by rearguard actions ‘in order to allow our troops to escape from the pincer movements the Germans are organizing everywhere’. Semyon Budenny, the commander of the Southwestern Direction, was not impressed and said, ‘I have powerful defences at Kiev and I can hold them as long as I have a soldier to fire a rifle or a horse to carry a gun. I guarantee that their little joke will cost the Germans more than all the rearguard battles proposed by Marshal Shaposhnikov.’ Stalin listened to both arguments and announced:

The Council of War orders the execution of the plan for a battle of attrition . . . without losing sight of the necessity of prolonging the battle as long as possible in order to permit the evacuation of the Ukrainian key industries.

The decision was to stand and fight to destroy the Germans.