CHAPTER 7

Breaking Through

(Zitadelle: 6–8 July)

Nurse Olga Iofe dressed one gaping wound and immediately moved on to the next. There was no time to waste. Her skills were precious and she could not linger, despite the pleas of the young men to comfort them. One soldier – a boy really – with an awful head wound asked Olga to pray with him. Being a good member of Komsomol she should refuse, but being a first-class nurse she placed the palm of her hand on his brow and closed her eyes while he mumbled a few pious words. A doctor yelled for her assistance and she left her patient to die alone.

It was a busy day at the aid station, which was now just five miles behind the front line. Olga could not even begin to guess how many men had died there since the German attack resumed on the second morning of the offensive. The 22-year-old had qualified as a nurse in early 1941 and volunteered on the second day of the war. It was, she said, ‘her duty to the Party and to the Motherland’. After a very brief induction into the army during which she learned to identify ranks and absorbed lists of ‘forbidden activities’, she was sent to the front where she had remained ever since. Yet Olga rarely took her full leave entitlement to rest and recuperate, despite the encouragement of her colleagues. If time away from the ward meant that men would die, then what right did she have to relax? In any case, she found it impossible to sleep away from her camp bed. A mattress was too comfortable and the quiet was intolerable. War had been a struggle at first, but now it filled her every fibre and she could not bear to be without it. Even the few hours that she had between shifts were spent strolling among the beds or storing the latest delivery of supplies that had been trundled along the salient’s dusty roads from the east. She slept little and ate even less. Olga knew that she could continue like this for weeks and even months if necessary. She knew because she had worked without a break during the Battle of Moscow, and for a similar stretch during the advance from Voronezh to Kursk during the previous winter.

The day before had been frantic, despite a recent increase in the size of the medical team and many weeks of preparation. Six surgeons and 18 nurses worked as a tight unit in their well-provisioned hospital, which was attached to a farmhouse. They had running water, which had been connected courtesy of the engineers who had also cut a new access road, allowing trucks to deposit casualties quickly. Orderlies carried the wounded from the transport to a triage tent where they were assessed. Olga worked with a team who prioritized patients – walking wounded were attended to after the stretcher cases; head wounds, abdominal wounds and those bleeding heavily were rushed through. Surgeons operated in three ‘theatres’ established in the building’s kitchen, parlour and only bedroom. Even so, casualties requiring treatment often exceeded the unit’s resources, and those deemed ‘without hope’ were condemned to die in a sweltering, fly-infested tent through which Olga wandered during her breaks. The dead, meanwhile, lay festering in the scorching sun, awaiting burial in a massive pit dug during May.

Although unlikely to be the day when the outcome of Operation Zitadelle was decided, 6 July was, nevertheless, full of potential. The powerful Wehrmacht were poised to attack the Soviets’ second-line defences, supported by a dominant Luftwaffe, and the defenders were facing the continuation of an intense and tormenting battle. Yet if the German forces could be contained, Rokossovsky and Vatutin recognized that, with time and resources on their side, they were well placed to weather the storm and provoke a devastating attrition. The two commanders also understood that their highly skilled and wily enemy remained capable of surprises. Just one slip could give Model and Manstein the opportunity to crack the front wide open and storm to their objectives.

The Voronezh Front was most vulnerable to being broken on 6 July after the Fourth Panzer Army’s efforts the previous day. Hoth’s advance may not have achieved all that Manstein had hoped, but it posed a distinct threat to Prokhorovka and Oboyan, if the 6th Guards Army were to be fractured. Indeed, it was now clear to the Soviet commanders that, although they had believed for weeks that the main German thrust would be delivered in the northern salient, this was not the case. As a consequence the 27th Army, which was to have been sent to Rokossovsky, was given to Vatutin instead. Even so, the immediate German menace would have to be faced by the overnight reinforcements, and much was expected of General Katukov’s 1st Tank Army along with the 2nd and 5th Guards Tank Corps, which were brought up to bolster the second-line defences.

Overnight considerable discussion took place about whether these assets would be best used in a counterattacking role or in defence. In any case, the understandable fear was that they could fall prey to the enemy’s powerful guns if they showed themselves on the battlefield. The decision was taken, therefore, to fix them in the defences by moving them into the emplacements that had been prepared for them weeks earlier. With just their turrets showing, they would not only prove an elusive target, but their guns would be a useful and reassuring presence to the infantrymen of the 6th Guards Army. Rifleman Sasha Reznikova recalls a T-34 arriving in his position near Syrtsev at around 0030 hours on 6 July:

We knew that the Germans were assembling for an attack and were deeply concerned at being crushed by its armoured weight. Although we had a number of anti-tank guns in the area they could be crushed in an instant. The arrival of a T-34 helped to settle our nerves. We helped to camouflage the tank with grass and what branches we could find . . . The tank commander gave us faith with his defiant attitude. We would hold out!

This reinforcement was a highly successful endeavour. It was carried out efficiently and without the Germans realizing the precise nature of what was going on. A delighted Katukov later remarked: ‘[The enemy] did not suspect that our well-camouflaged tanks were waiting for him. As we later learned from prisoners, we had managed to move our tanks forward unnoticed into the combat formations of Sixth Guards Army.’

Paul Hausser’s II SS Panzer Corps had also been busy during the few precious hours of darkness that early July offered. Fierce fighting continued in some areas as both sides used the cover of the night to improve their positions. At the tip of Das Reich, for example, acting Panzer Grenadier company commander SS-Untersturmführer Krüger spent six hours leading his unit in hand-to-hand fighting during which he was twice wounded. Remaining with the company, he continued to lead his men as they wrestled with several T-34s. Darting forward with a magnetic mine grasped tightly between muddy hands, Krüger was grazed by a round, which ignited a smoke grenade in his pocket and set his trousers on fire. Ripping the flaming cloth from his legs, he continued his attack on the T-34 in his underwear and succeeded in knocking out the tank.

Elsewhere, the front was quieter and the resupply of ammunition, fuel and other necessities took place without difficulty while commanders received their orders. Whatever the situation, and no matter how much sleep the tired troops had managed to snatch during the brief respite, at 0300 hours – accompanied by another strong artillery bombardment and streams of aircraft – the three divisions struck again. LAH and Das Reich pushed forward on a six-mile front northwards, led by 120 tanks with the Tigers at the point of the Keil. Their orders were to penetrate the heavily mined defences southeast of Yakovlevo and advance to the Pokrovka–Prokhorovka road. Hausser anticipated nothing less than the intense fight that ensued, but he also expected his men to break through the line and he was not disappointed. The Tigers, despite their lack of mobility, proved difficult for the Red Army to stop. Once again, well-aimed rounds achieved little more than shaking the tanks’ occupants, although when Obersturmführer Schütz’s Tiger took a direct hit and the driver’s glass vision block struck him in the stomach, he needed more than a couple of minutes to compose himself.

The Soviet second line, despite its reinforcement, could not contain the power of II SS Panzer Corps, and after a desperate period during which 88mm guns picked off strong points, the defences were breached. A wedge of panzers prised open the gap and the armour dashed through while the grenadiers mopped up. The Soviets’ plan to slow the corps while more substantial defences were readied came into play. Centres of resistance, which had been created in places conducive to tenacious fighting back, were supported by a counterattack. One such position, Hill 243.2 on the approach to Luchki (just south of the road to Prokhorovka), was covered by minefields, dug-in tanks, antitank guns, entrenched infantry and heavy artillery, which continued to pound the Germans engaged in breaching the second line. While the Germans were deciding how best to seize the position, based on information being supplied by reconnaissance units, the remnants of the 51st Guards Rifle Division and tanks of the 3rd Mechanized Corps from Yakovlevo, Pokrovka and Bolshie Maiachki launched successive counterattacks into the corps’ left flank.

As panzer grenadiers were sent to deal with this destabilizing development, the armour pressed forward to batter holes in the Soviet defences. Michael Wittmann’s LAH Tigers were ordered to destroy a battery of heavy 152mm guns that had been identified in a distant wood. The platoon advanced cautiously, utilizing whatever dead ground they could find and avoiding the enemy in order to maintain surprise. After two hours of careful infiltration, they finally took up firing positions several hundred yards from the target. On Wittmann’s order, the five 88mm guns opened up simultaneously. The Soviet guns were shattered and their crews flung across the gun pits. Most of those who survived the initial salvo were caught by subsequent shells and the explosion of the battery’s ammunition, which ripped through the position. The few gunners left alive fled the chaotic scene and were followed by the Tigers to a second battery, which was also destroyed.

Hill 243.2 was eventually taken after the arrival of LAH’s towed artillery, assault guns and werfer batteries, which lent their support to the attack. Mikhail Katukov later wrote:

Although it was noon, it seemed like twilight with the dust and smoke hiding the sky. Plane engines screamed as machine gun bursts rattled. Our fighter planes tried to drive the enemy bombers back and prevent them from dropping their fatal loads on our positions. Our observation post was only four kilometres from the forward line but we were not able to see what was happening in front because a sea of fire and smoke cut off our sight.

The Luftwaffe had indeed sent some Stukas and Ju-88s to assist but – as became common on 6 July across the salient – their impact was often not as great as it had been on the previous day because commanders could not fulfil all of the requests that they received for support. With too few aircraft for the job, a dearth of petrol, oil and lubricants and the increasing necessity to repair battle damage and conduct routine maintenance, the Luftwaffe was forced to prioritize calls upon their services. Moreover, because air-support missions took precedence over the ongoing attempt to win air superiority, German fighters were no longer in a position to intercept all Soviet airstrikes. The situation was not helped by so many flak weapons being diverted to ground duties. In such circumstances, the Soviet airforce could begin to assert itself more forcefully.

The Germans had not been stopped, but once again their thrust had been slowed to a crawl. Luchki fell in the early afternoon as Das Reich pressed forward on LAH’s left flank, rebuffing various attempts made by the 5th Tank Guards Corps. That day, the LAH war diary admits to 84 dead and 384 wounded. By the evening, the nose of Hausser’s penetration was almost touching the village of Teterevino, just seven miles southwest of Prokhorovka. However, the forward elements of the corps were extremely exposed, as one German LAH officer observed that evening: ‘We could still capture Teterevino. But could we stay there? It was getting darker. We were worried about our flanks, so we set up defences.’

In fact, the flanks of the entire corps were exposed. During the day, the 49th Tank Brigade reinforced the men at Pokrovka and the 31st Tank Corps moved into Bolshie Maiachki to counterattack. However, it was the lengthening right flank that caused Hausser more concern, not least because its defence was robbing him of Totenkopf, which was lagging behind to protect it. One of Hoth’s precious mobile divisions had to ward off the attentions of the 2nd Guards Tank Corps and the 96th Tank Brigade from across the Lipovyi–Donets River throughout the day, due to a lack of infantry to replace it. Indeed, by the evening of 6 July, more than 30 per cent of Manstein’s armour was being used in the secondary role of flank defence. As David Glantz and Jonathan House have observed, across the front ‘obscure battles along the flanks were already quietly assuming decisive importance’.

The reason why II SS Panzer Corps’ right flank was wide open was the continued failure of Army Detachment Kempf to make adequate progress. Immediately recognizing the importance of stymieing Manstein’s progress on the right of his attack, Vatutin placed considerable emphasis on undermining it and drawing its two corps eastwards, a task that General Shumilov’s 7th Guards Army carried out with aplomb. Throughout the day, Corps Raus fended off counter attacks, which the commander called ‘a considerable defensive victory’. He says that ‘thanks primarily to the excellent performance of our infantry in permitting the Soviet tanks to roll over them . . . which succeeded in separating the enemy tanks from their own infantry supports . . . [t]he Russian infantry attack broke down in front of our lines, which now held without budging.’ With the two infantry divisions on Kempf’s right flank providing protection, III Panzer Corps would carry out the main attack. It was, Hoth emphasized to Hermann Breith, imperative that his armour find a way forward so that the 168th Infantry Division could move up to relieve Totenkopf. Thus, the 7th and 19th Panzer Divisions led the attack on the second morning of Zitadelle and were finally joined by the 6th Panzer Division in the afternoon, when it had finally crossed the Northern Donets. All three were thwarted by stout defence by the 81st, 73rd and 78th Guards Rifle Divisions, whose minefields, trenches and anti-tank strong points robbed the formations of the momentum that they needed. Panzer Grenadier company commander Leo Koettel noted in his journal:

6 July: Today we took [Kreida Station] but we have barely begun to move. We advance a few hundred metres, and then stop again due to a minefield, artillery, rockets and counter-attacks . . . We have been roasting in the heat. We are only now managing to take objectives that should have fallen to us yesterday morning. It is very disappointing.

The Tigers from the 503rd Heavy Tank Battalion supporting the divisions did what they could but found the going extremely difficult. Those attached to the 6th Panzer Division were constantly frustrated by the Soviet defences, as radio operator Franz Lochmann explains: ‘[we] came to a halt under heavy anti-tank fire in the midst of a minefield in front of an anti-tank ditch . . . The combat engineers who advanced suffered fearsome losses. They were decimated before our eyes while they cleared entire belts of mines.’ For the exasperated Clemens Graf Kageneck, the 503rd’s commander, the day had been another bad one. He wrote:

Never before had a major German offensive operation had to master such a deeply echeloned and imaginatively organized defensive system. What von Manstein and von Kluge had feared since May, that with every week’s delay the Russians would create a nearly impenetrable fortification, was what we now had to face.

In late afternoon, the 6th Panzer Division did manage to get the 73rd Guards Rifle Division’s left flank to curl up, and force it to withdraw to a low ridge north of Gremiachii to Batratskaia Dacha, but it was backed by three more Guards Rifle Divisions and a fourth was en route. Thus, by the end of the day, although some progress had been made towards the Soviets’ second line of defences, Army Group Kempf had been deftly contained and II SS Panzer Corps was denied the protection that it needed.

General Knobelsdorff ’s XLVIII Panzer Corps, meanwhile, recommenced its wrestle with the Soviet first line. Here the Panzer Grenadier Division Grossdeutschland, flanked by the 3rd and 11th Panzer Divisions, forced the 67th Guards Rifle Division to withdraw to the second-line positions held by the 90th Rifle Division and elements of the 3rd Mechanized Corps. Although its 167th Infantry Division struggled to keep pace – thus leaving the left flank of II SS Panzer Corps bare – the rest of the corps made excellent progress. Benefiting from some strong Luftwaffe support, it overcame various intermediate positions and achieved some impetus in its drive forwards. ‘It was a hard slog, but ultimately successful,’ wrote combat engineer Peter Maschmann to his father. ‘We felt progress was being made and confidence washed over us.’ Probing the enemy’s second line for weak spots, 3rd Panzer Division’s reconnaissance battalion reached the River Pena near Rakovo under heavy fire from the north bank. Here it found the river to be shallow, but the approaches were marshy and the banks were saturated, which would make it extremely difficult for armour to cross. Knobelsdorff had demanded that ‘momentum be maintained whenever possible’, but the division informed corps that the Pena should be avoided. In a deft move, Knobelsdorff quickly reorientated the corps northeast to more favourable terrain east of Alekseevka through Lukhanino and Syrtsevo. Grossdeutschland and the 11th Panzer Division were able immediately to set about the Soviet second line. An observer later noted:

The entire area has been infested with mines, and the Russian defence along the whole line was supported by tanks operating with all the advantages of high ground. Our assault troops suffered considerable casualties, and the 3rd Panzer Division had to beat off counterattacks. In spite of several massive bombing attacks by the Luftwaffe against battery positions, the Russian defensive fire did not decrease to any extent.

Peter Maschmann and his team set to work removing the mines that were stalling the attack, and took heavy fire in the process:

It was not a job for the faint-hearted. I joined hoping to build great bridges – a passion of mine as my father was a civil engineer and I hoped to follow in his footsteps – but I ended up in a mine-clearing team! Life expectancy was not high. In a battle such as this, it could be measured in days, but there were a few of us that got lucky . . . The belts before the Soviet line at Lukhanino were particularly dense and it was disappointing to be held up again after our excellent progress earlier in the day. But that was the enemy’s aim. To slow us down and grind us into those never-ending, god-forsaken and blood-soaked fields.

The Grossdeutschland’s history explains that, having carved their way through the mines, the division then had the usual Soviet defences to overcome:

[A] heavy tank battle developed in the broad corn fields and flat terrain there against the Bolsheviks grimly defending their second line of resistance. Earth bunkers, deep positions with built-in flame-throwers, and especially well dug-in T-34s, excellently camouflaged, made the advance extremely difficult. German losses mounted, especially among the panzers. The infantry fought their way grimly through the in-depth defensive zone, trying to clear the way for the panzers.

Although Grossdeutschland managed to pierce the line at Lukhanino, on its left the 3rd Panzer Division was held on the Pena, and on its right the 11th Panzer Division and the 167th Infantry Division’s position framed a 52nd Guards Rifle Division salient, with its nose just to the west of the village of Bykovka.

Reflecting on the day, Hoth was doubtless pleased that the Fourth Panzer Army continued to show promise and was a step closer to freeing itself from the web of Soviet defences, but he had fallen significantly behind Zitadelle’s timetable. By this time, his force should have been across the Psel rather than still smashing its way through the defences either side of Pokrovka. Mechanical losses had been high with at least 300 of his armoured fighting vehicles (AFVs) lost either to enemy action or mechanical failure. Grossdeutschland, for example, had only 80 of its 350 supporting tanks still operational. II SS Panzer Corps reported approximately 110 AFVs as ‘fallen out’ on 6 July and XLVIII Panzer Corps reported 134. These figures include many tanks and assault guns that were repairable, but losses to Manstein for the first two days of the battle were 263 machines from all causes and around 10,000 men. Richthofen’s Luftflotte 4, meanwhile, had lost more than 100 aircraft over the same period, and its operations were further hamstrung by ongoing maintenance requirements and fuel shortages. As a consequence, the Luftwaffe launched 873 daylight sorties in the southern sector that day, while the Soviets’ 2nd Air Army – having already replaced the aircraft lost in the opening air encounters – mounted an impressive 1,278. Luftflotte 4s Chief of Staff, General Otto Dessloch, was well aware of the increased Soviet air presence over the battlefield, but there was little he could do about it other than concentrate aircraft where they were most urgently required while eking out petrol, oil and lubricant supplies.

The Soviets were still strong on 6 July – far stronger than the Germans thought possible – but Vatutin had problems. There was a big hole in his defences and by midnight he had committed almost all of his Front reserves. The Voronezh Front commander dispatched a report to Stalin at 1830 hours and requested reinforcement. The Supreme Commander, having analyzed the situation with his staff in Moscow, was convinced of the seriousness of the position and released Lieutenant-General Pavel Rotmistrov’s 5th Guards Tank Army (29th Tank Corps, 5th ‘Stalingrad’ Mechanized Corps and the additional 18th Tank Corps) from the Steppe Front reserve. The formation was provided with the stipulation that Vatutin must continue ‘to exhaust the enemy at prepared positions and prevent his penetration until our active operations [counterattacks] begin’. There was to be no precipitate counterattack.

Konev was not happy about the piecemeal dismemberment of his reserve but a personal call from Stalin stopped his bleating and the formation was soon moving west. The aim was for the Army to be in the vicinity of Prokhorovka by 10–11 July, in time to deploy its 600 plus tanks, supporting artillery and infantry to prevent a decisive breakthrough by II SS Panzer Corps and XLVIII Panzer Corps. The Southwestern Front’s 2nd Tank Corps and the 5th Guards Army’s 10th Tank Corps were ordered to go immediately to the Prokhorovka area to provide the support that the Voronezh Front needed from 8 July. Vatutin’s plan did not change – he would continue to wear down Manstein’s force and use the reinforcements to finish off the process.

There was little time for rest that night, and in some places the fighting continued without a break through to the morning. The next day, 7 July, dawned dull, ushering in a period of cooler, wetter weather across the battle lines. XLVIII Panzer Corps and II SS Panzer Corps attacked out of a thin mist across a 30 mile front, the tank crews and infantry easing themselves forward once more, their tired, aching limbs yearning for respite and a warming sun. LAH surged towards Greznoye; Das Reich filled in the positions that it left behind on the road to Prokhorovka, supported by the inevitable Stuka formations. On this day, although half of Luftflotte 4 was temporarily reassigned to assist with Model’s attack in the north, the remaining 500 aircraft had a great impact. One pilot, Captain Hans-Ulrich Rudel of III/Stuka-Geschwader2, was to become the most decorated German serviceman of the war and the only man to be awarded the Iron Cross with Golden Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds.

During February, the teetotal and non-smoking Silesian had become the first pilot to complete 1000 sorties, and in Zitadelle he flew the G-2 Stuka (‘Kanonenvogel’) armed with twin 37mm guns. Born on the second day of the Battle of the Somme in 1916, Rudel was much admired by Marshal Ferdinand Schörner, who later said, ‘Rudel alone replaces a whole division.’ The ‘Stuka Ace’ recognized in his autobiography that he was lucky to have survived so long, considering the vulnerability of the relatively slow and awkward Stukas. Zitadelle was a last hurrah for these dive bombers, which were being picked off with increasing frequency by Soviet fighters and flak. Yet, as Rudel argues, ‘The aircraft had a devastating impact on the enemy and was irreplaceable.’ He flew countless missions during the Battle of Kursk and claimed scores of tank kills. Rudel explains:

We tried to hit the tanks in the weakest spots. The frontal part is always the strongest . . . It is more vulnerable along the flanks but the best aiming part is the rear where the engine is located, covered by thin armoured plating . . . This is where it pays to hit them, because where there is an engine there is always fuel! It is quite easy to spot a moving tank from the air, the blue engine exhaust smoke is a giveaway.

The salient that Hausser’s corps was creating towards Oboyan and Prokhorovka was a clear threat to the integrity of the Soviet defences, and Vatutin re-emphasized his order for subordinates to put it under intense pressure to stop its expansion. This order was carried out throughout the day, and tenacious defence was mixed, wherever possible, with intrepid counterattacks. At Teterevino, for example, elements of LAH and Das Reich launched an attempt to break into the village after its defences had been softened up by Henschel Hs-129s and Focke-Wulf 190s. The Germans broke through the outer defences and then became entangled in the main defensive line. A protracted battle ensued, with T-34s from the 5th Guards Tank Corps, artillery and anti-tank guns. Tigers eventually managed to get through, and the village was seized during the late afternoon, along with the command post and entire staff of a rifle brigade. What had been expected to be a short, sharp smash and grab had turned into a bloody and gruelling battle. All the while, Totenkopf ’s great potential was nullified as it continued to be fully engaged in protecting the corps’ lower eastern side. Thus, although Greznoye and Teterevino were taken by Hausser’s division on 7 July, it turned out not to be a day of breakthrough and exploitation, but another day of slog and grind. In the circumstances, he had little option but to continue to plug away at the Soviet defences and hope that another day’s offensive action would force them to succumb.

As Hausser’s corps struggled on northeast of Pokrovka, Knobelsdorff’s XLVIII Panzer Corps continued its attack on the Soviet second line with around 300 tanks, including just 40 remaining Panthers. By around 0600 hours a crunching battle was developing west of Pokrovka as the Soviets refused to give ground and retaliated against the Wehrmacht’s violence with their own artillery bombardments and aerial attacks. However, the Grossdeutschland Division had ruptured defences the previous evening, and Walter Hoernlein was determined to batter away until he broke through, but progress was slow. The Panthers suffered heavy losses when they waded into a minefield, which had to be dealt with before the grenadiers could start to clear the bunkers, trenches and emplacements in close-quarter action. A Soviet observer noted: ‘During repeated attacks, by introducing fresh forces, the enemy penetrated the defensive front and began to spread in a northern and northwestern direction. The brigades withdrew in bitter fighting.’ Gradually, the Soviets were pushed back to the outskirts of Syrtsevo, leading XLVIII Panzer Corps’ Chief of Staff, General Friedrich von Mellenthin, to write: ‘The fleeing masses were caught by German artillery fire and suffered very heavy casualties; our tanks gained momentum and wheeled to the northwest. But at [Syrtsevo] that afternoon they were halted by strong defensive fire, and the Russian armour counterattacked.’ Katukov did indeed unleash over 100 T-34s of the 3rd Mechanized and 6th Tank Corps to halt Grossdeutschland’s surge, but despite air support provided by Pe-2s, Il-2s and fighters, the guns of the Tigers and Panthers and divisional artillery fragmented the riposte and forced the Soviets back. Yak fighter pilot Artyom Zeldovich recalls flying over the battlefield:

The ground gradually lit up with flaring tanks. Some of them were German, but most of them were ours. The sky filled with a dense black smoke . . . We managed to keep the enemy’s aircraft away for periods, but sometimes they broke through when we returned to base to refuel and rearm. When we returned, more tanks were burning and the battle had moved forward several hundred metres . . . It was clear that the Germans were heading for Syrtsevo and we had orders to stop them achieving this at all costs. Flying over the sector it was easy to see why. The road system was opening up, Oboyan was close by with Kursk not so far beyond it . . . The battle was a battle of resources, but it was also a test of wills. Looking down at Syrtsevo – an inferno – I wondered whose will would break first.

Neither side looked likely to crack on 7 July; both fought with no quarter given throughout the day. That evening, as the Soviets quickly reinforced Syrtsevo with elements of the 67th Guards Rifle Division and 60 tanks from the 6th Tank Corps, Grossdeutschland drew up towards the outskirts only to be confronted by yet another minefield. Even as work began to clear lanes through it in preparation for a renewed attack by the division the following morning, Hoernlein directed his Tigers to outflank the village. It was a bold move. The division needed a decent pause to recuperate after its exertions, but the commander was desperate to build up whatever impetus he could before darkness. His frustration must have been immense, therefore, when he learned that the manoeuvre had floundered due to the mechanical breakdown of Grossdeutschland’s residual Tigers. It was not the first time in the battle that the technical frailties of these ‘wonder weapons’ had severely hampered promising tactical situations. Indeed, mechanical breakdown and temporary disablement were far more common causes of panzers being put out of the front line than tank kill. As a consequence, mobile field workshops had an important role to play in ensuring that the Germans’ armoured fleet was inconvenienced as little as possible by minor ailments. Mechanic Karl Stumpp testifies:

We had to keep pace with the attack as much as possible which meant that vehicles were taken to a place of relative safety, camouflaged and guarded until we could arrive and do whatever we needed to do to get the vehicle back into battle again . . . Occasionally the heavy tanks needed more specialist attention that would follow on behind us, but we could deal with most defects. We were targeted by Soviet aircraft because the tank was immobile, but we were protected by flak and this helped . . . During this period in the battle mine strikes were common and we could repair suspension damage in just a few hours although it sometimes took longer . . . Mechanical problems were not uncommon, particularly in the Panthers and Tigers. The Panthers had numerous faults which were not difficult to fix, but sometimes we lacked the spare parts. Problems with Tigers occurred mainly when the crews had not had a chance to undertake their own daily maintenance routines on their machine because of the intensity of battle.

Although just a few Tigers were destroyed during Zitadelle, the Soviets officially logged the destruction of hundreds. Indeed, on 7 July the Soviet Information Bureau made a remarkable announcement about the opening day of Zitadelle: ‘The backbone of the German offensive thrust, the Tiger units, were singled out for special attention by our anti-tank units. They suffered heavy losses. At least 250 of these large tanks went up in flames on the battlefield.’ A couple of days later the same agency declared that a further 70 Tigers and 450 other tanks had been destroyed on 7 July. Thus, by the end of the third day of battle, Moscow laid claim to an extraordinary 1,539 tank kills.

Although possibly just a massive over-estimation of their own destructive virility, the figure was probably plucked out of the air for propaganda effect. It might also reveal the grip that the Tiger had on the Soviet imagination. Built up to represent the power of the Wehrmacht on the fighting front, the Soviets would take delight in dismantling the image of invincibility that the machines engendered. If the Tigers could be defeated, then so could Zitadelle and with it Germany’s offensive power in the East. What the official government statements did not say, of course, was that the Red Army was also haemorrhaging casualties and material losses. Operations to blunt the German advance were proving extremely costly. Vatutin was certainly aware of this reality and was sensitive to the fact that the High Command’s attritional strategy was not without cost to his finite resources.

The Soviets were busy damming the front against a rising German tide, and if the dam burst, Manstein would gratefully send his forces to flood the rear of the Voronezh Front. The Soviets were feeling vulnerable in the south, which led Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin’s political representative at Vatutin’s headquarters, to declare to the assembled commanders that evening, ‘The next two or three days will be terrible. Either we hold out or the Germans take Kursk. They are staking everything on this one card. For them it is a matter of life or death. We must see to it that they break their necks.’ The battle was reaching a critical point in the sector. Vatutin issued a rash of orders and made strategic redeployments. He directed, ‘On no account must the enemy break through to Oboyan.’ The 40th Army was moved into the line from its duties defending the quieter face of the salient, and two counterattacks were to be delivered the next day against the Fourth Panzer Army. The Southwestern and Southern Fronts were directed to prepare for diversionary attacks, to take place before the counterattacks, to ‘tie down enemy forces and forestall manoeuvre of his reserves’.

The operational situation in the southern sector of the Kursk salient remained finely balanced as darkness fell on 7 July. As a result, the battle continued to rage unabated in some areas. The Grossdeutschland history noted, for example: ‘Night fell but no rest. The sky was fire-red, heavy artillery shells shook the earth, rocket batteries fired at the last identifiable targets.’ In areas of great tactical or operational importance, units and formations did not differentiate between night and day as both sides sought to improve their positions. Pioneer Henri Schnabel did not get much sleep during this period and was finding it difficult to cope:

This was the fourth night of our battle, because we had cleared minefields the night before the offensive began. We were exhausted because there was no let up in demands for our services. We lived on adrenaline and 10 minutes of sleep here, five minutes there. I had a crunching headache and often fell asleep standing up . . . Considering the nature of our job, this was hardly ideal. We were totally drained.

Red Army infantryman Feliks Karelin was also drawing on his last reserves of energy. He had been in the front line when the Germans struck on the 5th and had withdrawn back to a position near Pokrovka by the night of the 7th:

I hardly recall the first days of the battle. They were a blur, but I remember that we did not sleep. Some men were in a worse state than I. One man I tried to wake as we moved back to a new position but he was so tired that he decided to stay in his shell scrape and take his chances. The position was overrun an hour later . . . The lack of sleep made it difficult to understand basic orders and to carry out simple tasks. I was confused and could barely operate as a soldier. However, we learned to take very, very brief naps which helped a little. I also found that enemy action was an excellent stimulant. I could be falling asleep on my rifle and with shells falling around me, but as soon as I was in danger from tanks or enemy [infantry] I would suddenly become alert. But as the days passed, this became increasingly difficult. My energy was being sapped.

Some of the troops had jobs that were so physically demanding that after the opening days of the battle, they could not carry on. One Tiger gun loader, for example, recalls: ‘It was extremely hot and we had to rearm three or four times [a day]. This meant repeating the process of taking on forty to fifty shells, throwing out the empty casings and reloading three of four times.’ Deemed physically incapable of continuing to fulfil his tasks, he was replaced. But for most there was no hope of relief and they had to make do with the few hours that darkness offered to ‘recharge’ before the next day’s action.

The first job that most units undertook on halting for the evening was to replenish their ammunition stocks, refill magazines and machine-gun belts, and take up any other supplies, weapons and equipment that were needed. This would be followed by time spent finding shelter, reorganizing kit and cleaning weapons. Tank and vehicle crews would use the time not only to take on fuel, water and ammunition, but also to carry out some basic maintenance on their machines. Once this had been done, the men would eat – ideally, a hot meal from a field kitchen, but often from a box of cold, uninspiring rations that barely replaced lost energy.

Then, with their chores completed, the troops would settle down for some rest. Some might curl up in a trench, ditch or shell scrape; others might set up a bivouac in the woods. Tank crews always spent the night with their vehicles, either sleeping in the open or in tents close by. Sentries had the difficult job of keeping watch while their comrades slumbered. It was a task beyond SS Senior Corporal Pötter on the night of 7–8 July. He fell asleep within minutes of taking up his position. Shaken awake by his furious platoon commander, Michael Wittmann, Pötter was reminded of the seriousness of the offence that he had just committed, before being told to get some sleep. Wittmann personally took over the corporal’s watch. Officers, of course, had responsibility for their men and so, in most cases, ate last, slept least and busied themselves with the day-to-day running of their units. Assisted by senior non-commissioned officers, they ensured that their men were in the best possible condition to fulfil their duties. Lieutenant Walter Graff, a panzer grenadier platoon commander, recalls:

My own tiredness was offset by the nature of my job. I had so little time to relax that I had little opportunity to feel tired. Of course, there were moments when I could hardly keep my eyes open, but I had responsibility for the lives of 30 men and so I could not afford to be anything other than completely focused. I also had to ensure that I was a role model to the platoon . . . As a result, I always tried to ensure that I was properly dressed, that I had shaved, that my boots were polished, my personal weapon was clean and that I conducted myself in a professional manner . . . Standards can slip very easily in battle, and that is when soldiers get into bad habits that can easily lead to casualties . . . I always ensured that I spoke personally to every man in my platoon every day about something unrelated to the war. I usually did this in the evening – if we were fortunate enough to be able to take a break – and would wander around the positions encouraging each, offering reassurance and a kind word.

Hardly refreshed, the men would be awoken, breakfasted, briefed and ready before the first light of a new dawn at around 0300 hours. Army Detachment Kempf’s war diary reveals that it was fighting night and day to get III Panzer Corps moving north to support Hoth’s advance, but despite its best efforts, it remained mired in a slogging match with the redoubtable 7th Guards Army. Immediately recognizing that he must ensure the Fourth Panzer Army was denied the support of Breith’s formation, Shumilov poured resources into his defences northeast of Belgorod and continued to occupy Kempf with bone-crunching counterattacks. In this way, the Soviets stopped the three panzer divisions from gaining any impetus towards Prokhorovka. The result was that III Panzer Corps was largely held before Shumilov’s second line, although by the evening of 8 July, the Tigers of the 503rd Heavy Tank Battalion leading the 6th Panzer Division had pierced their way in and helped develop a 10 mile deep, two and a half mile wide salient to Shilakhovo.

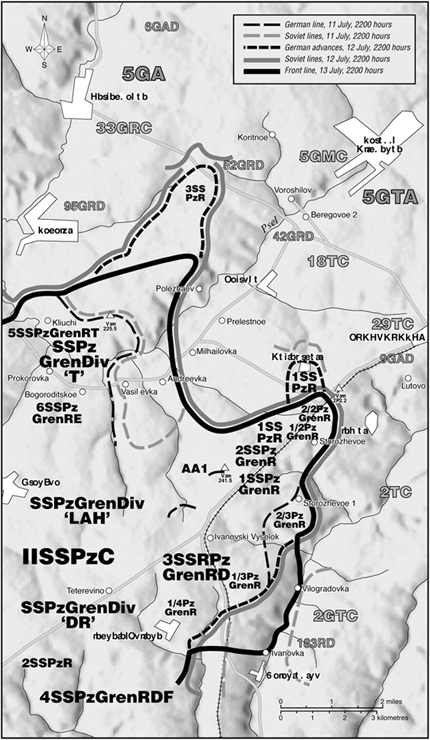

Meanwhile, both II SS and XLVIII Panzer Corps resumed their offensives with vigour at around 0500 hours on 8 July. LAH remained at the front of Hausser’s corps, two panzer grenadier regiments from Das Reich held the line from Teterevino along the Lipovyi–Donets River, and Totenkopf (at last) began to transfer some of its flank protection duties to the infantry. Since III Panzer Corps had signally failed to provide the support expected of it, and Knobelsdorff ’s panzers had linked up with LAH at Yakovlevo, the 167th Infantry Division was moved from Hausser’s left flank to his right. This allowed the leading elements of the relatively unscathed Totenkopf to support LAH’s attacks on the 8th while the remainder of its units moved north to assume duties at the point of the attack on the following day. The reinforcement of II SS Panzer Corps’ attack reaped immediate benefits because the two divisions worked in concert to expand the breadth of Hausser’s attacking front. Caught by surprise, the Soviets were forced to relinquish Bolshie Maiachki early in the morning and to withdraw from Gresnoe back north to the Psel River.

The corps also managed to repel Vatutin’s much-vaunted counterattacks, which were unhinged by Hausser’s own early advance, the late arrival of critical units and some poor coordination. First, 31st Tank Corps’ strike was rebuffed as it emerged from Malye Maiachki, and then the newly arrived 10th Tank Corps was seen off as it pushed down the road from Prokhorovka towards Teterevino. The fighting was passionate and ferocious. One experienced German divisional gunner wrote in his diary that evening:

We are under extreme pressure and the guns have been in action since 0430 hours. By noon we had run out of ammunition and had to wait two hours for resupply. It arrived with Soviet aircraft . . . Enemy attacks have diluted our offensive . . . This is the most intense fighting that I have experienced. We must break through soon or face the consequences.

Although the Soviet thrusts had failed to bring Hausser’s advance to a halt, by fragmenting into a series of local actions that lasted for the rest of the day, they did ensure that the corps was burdened with the need to defend itself to the detriment of its forward momentum. A further attempt to hamper progress was launched against the corps’ extended left flank and the newly arrived units of the 167th Infantry Division. Seeking to cut II SS Panzer Corps’ lines of communication, the 2nd Guards Tank Corps had been ordered to attack westwards from some woods around the village of Gostishchevo (10 miles north of Belgorod). The impact could have been devastating because the Germans did not know that the formation was assembling for an attack, but it was spotted just in time by Hauptmann Bruno Meyer leading a flight of Henschel Hs-129s on a routine reconnaissance mission. Meyer’s aircraft, together with some Fw-190s armed with SD-2 cluster weapons, proceeded to ravage the Soviet tank corps. The young officer later recalled: ‘Wave after wave was emerging from the woods tugging gun mountings, mortars, anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns by hand behind them . . . they came over a frontal area [five to six miles] wide. Then followed the tanks.’

The infantry were decimated by the cluster bombs but carried on marching forward despite the havoc surrounding them. It took the cannons and machine guns to rip through them before their stoicism was fatally undermined and they finally fled to the relative sanctuary of the woods. As they did so, their tanks were ripped apart by waves of Henschels sporting MK 103 30mm cannon. Within an hour some 50 T-34s had been rendered inoperable and two hours after that another 30 had been destroyed and thousands of dead lay across the battlefield. Although the bulk of the corps lived to fight another day, it was, nevertheless, an historic moment – the first time in history that a tank formation had been stopped by air power alone.

II SS Panzer Corps had managed to nudge forward beyond Greznoe on the fourth day of the offensive, but had once again failed to break the Soviet defences and was left battered and bruised by a string of Soviet counterattacks. The story of containment and counterattack was replicated in Vatutin’s defence against XLVIII Panzer Corps. Knobelsdorff also attacked at dawn. Grossdeutschland took a line along the east bank of the Pena, the 3rd Panzer Division tucked in below its left flank and the 11th Panzer Division provided support on the right, advancing up the road to Oboyan. Grossdeutschland’s thrust towards Syrtsevo was countered by Soviet armour, initially a cordon to slow the German advance, and then, later in the morning, General Krivoshein’s 3rd Mechanized Corps unleashed a counterattack by 40 T-34s. It was another desperate encounter. Ten Soviet machines were destroyed by Grossdeutschland’s eight serviceable Tigers and a collection of Mark IIIs and Mark IVs. Pulling back, having successfully inhibited Hoernlein’s drive, the remaining Soviet tanks, guns and infantry organized themselves to protect the village once again. ‘I have to say that the Germans were extremely tenacious – our equals in that regard,’ says Sasha Reznikova. ‘They did not give up and we knew that they wouldn’t. They fought to the last when isolated and attacked until they could attack no more. I suppose they had no alternative. The enemy was desperate and had to drive forward at every opportunity.’

Inevitably, the Soviet defence began to crumble as Grossdeutschland launched a series of blows against Syrtsevo. Krivoshein’s runner arrived at corps headquarters with regular reports: ‘The 3rd Company of Kunin’s battalion has lost all its officers. Sergeant Nogayev is in command . . . Headquarters of 30th Brigade has received a direct hit. Most officers killed. Brigade commander seriously wounded.’ The defence began to waver and the Germans were not slow to exploit the confusion that affected the Soviet line as it began to lose its shape. By the early afternoon, units of Grossdeutschland had moved into the village and, after some close-quarters fighting, finally took their hard-won prize. They were immediately hammered by Soviet artillery firing from the west bank of the Pena.

Watching the fall of Syrtsevo with Katukov at the 1st Tank Army headquarters, with a sense of growing doom, was Lieutenant-General N.K. Popiel, the political representative, who later wrote:

We saw in the distance a large number of tanks. It was impossible to distinguish damaged tanks from those undamaged. The row began moving. Only a burned field a few hundred metres wide, nothing else separated us from the enemy. Katukov did not take the field glasses from his eyes. He mumbled: ‘They’re regrouping . . . advancing in a spearhead . . . I think we have had it!’

The men were witnessing Grossdeutschland’s regrouping as the division began its next move northwards. As the 11th Panzer Division dealt with a number of Soviet tank attacks on the east flank, Hoernlein’s formation pressed on, hoping to take some high ground to the east of Verkhopenye after a signal had been received declaring that the town had been taken in a daring coup de main. However, as the division’s Armoured Reconnaissance and Assault Gun Battalions scouted ahead, they unexpectedly came across a Grossdeutschland panzer grenadier company in Gremutsch. It soon became apparent to the unit’s embarrassed commander that he had not taken Verkhopenye as reported, but instead held a village several miles south of his objective. Even as the ramifications of the mistake were being digested, more than 40 Soviet tanks were attempting to retake the hamlet from the northeast. They were met by the assault guns, which had already been formed into a defensive perimeter by its 26-year-old commander, Major Peter Frantz. In a text-book action during which the enemy’s armour was lured into carefully baited traps and destroyed piecemeal, Frantz systematically beat the Soviets away. Recounting the episode in some detail, Paul Carell concludes Frantz’s story by dramatizing the final minutes of the battle:

[A] pack of T-34s and one Mark III were fast approaching the slope. Sergeant Scheffler had his eyes glued to the driver’s visor. The gun aimer was calmness personified. ‘Fire!’ Tank after tank was knocked out by the 75mm cannon of armoured reconnaissance and assault gun battalions. The Soviet commanders attacked time and time again. Their wireless traffic showed that they had orders to break open the German line regardless of the cost. Seven times the Russians attacked. Seven times, they flung themselves obstinately into Major Frantz’s traps. After three hours, 35 wrecked tanks littered the battlefield, smouldering. Only five T-34s, all of them badly damaged, limped away from the smoking arena to seek shelter in a small wood. Proudly the major signalled to the division: ‘35 enemy tanks knocked out. No losses on our side.’

By early evening, Grossdeutschland’s armour approached Verkhopenye as yet more counterattacks struck the division’s exposed flanks. Both the 3rd and 11th Panzer Divisions were also fending off strong enemy probes, so there was little that Hoernlein could do but absorb the blows and press on with his attack on the town. It was testament to the resilience of the division that the Soviets were not only held off, but a clutch of tanks and panzer grenadiers eventually penetrated their objective. As they did so, a furious contest developed around the perimeter, as one eyewitness describes:

Ferocious, unparalleled tank battles ensued on the flats of the steppe, on hills, in gorges, gullies and ravines, and in settlements . . . The scope of the battle was beyond all imagination. Hundreds of panzers, field guns and planes were turned into heaps of scrap metal. The sun could barely be seen through the haze of smog from thousands of shells and bombs that were exploding simultaneously.

During mid-afternoon, a battalion of panzer grenadiers, a battalion of tanks and a handful of Panthers had assembled on the eastern approaches to the town and taken up defensive positions. Anti-aircraft gunner Lieutenant Haarhaus later recalled:

The Russian ground-attack aircraft were quickly on the scene. They came sweeping in every two hours. Each aircraft dropped its 50 to 60 bomblets, strafed the infantry positions and then disappeared. For those of us in the Flak our mission had begun.

Sending up a stream of fire into the cloud-strewn sky, the muzzle flashes were soon spotted and their positions strafed. The gun teams instinctively cowered behind their weapon’s flimsy armoured shield. Haarhaus continues: ‘The rounds crack, whistle and crash around us. Only a few metres above us, the aircraft zoom over our guns, fly a broad loop and renew their attack. Those bastards have guts! Colossal! That afternoon, we knocked three of them from the sky. But we also lost half of our crew to strafing.’

Verkhopenye was not taken on the 8th, but as dusk fell plans were made to seize the town on the next day. It was to be a busy night for the men of Grossdeutschland in their exposed positions. They not only refuelled and resupplied, but also had to ward off numerous Soviet counterattacks in the darkness, supported by low-flying Po-2s and Il-2s. The attention the Soviets paid to this inconspicuous town revealed Vatutin’s fear that Manstein was on the verge of fashioning a breakthrough. Fearful of his remaining troops being destroyed unnecessarily in a fight to the last in Verkhopenye, the commander of the Voronezh Front ordered them to withdraw during the night of 8–9 July and establish new defences north of the town across the Oboyan road and along the Solotinka River, forward of Sukho-Solotino and Kochetovka to the Psel River. Here, the 31st Tank Corps and remnants of the 3rd Mechanized Corps would be joined by the 309th Rifle Division (from the 40th Army), the 29th Anti-Tank Brigade, two fresh tank brigades and three anti-tank regiments, which were to link in to established positions held by the 6th Tank Corps farther west. Along this line Vatutin hoped to halt Hoth’s Fourth Panzer Army long enough to feel the force of the armoured counterattacks being mounted around Prokhorovka.

Manstein, meanwhile, believed that, although his offensive had fallen considerably behind Zitadelle’s timetable, at last he was about to rent the Soviet defences asunder. ‘The prospects for a breakthrough remain good,’ the field marshal explained to Model on the night of the 8th. ‘We must not fail to ensure that we give the enemy’s defences no time to settle and yet retain the power to exploit our successes.’ However, Hoth was concerned by intelligence that ‘considerable Soviet armoured forces’ were massing on his right flank, and Knobelsdorff ’s sources were telling him of the danger posed by the 6th Tank Corps on his left. The offensive could not continue without taking these threats into consideration. During the evening of 8 July, therefore, Manstein, Hoth, Hausser, Knobelsdorff and Kempf were locked in discussion about how to proceed. Although the Germans were making ground in the south, they were doing so slowly and suffering considerable losses in the process. In such circumstances, it would have been extremely beneficial to Zitadelle had the Ninth Army been powering through Rokossovsky’s defences in the northern sector of the salient.

Model’s advance had not been dramatic on the first day of the offensive, but the infantry-based attack had made progress towards the second line of defences. It was on these positions, stretching from Samodurovka to Ponyri and protecting the Olkhovatka heights, that XLVII and XLI Panzer Corps would focus their attention for the rest of the operation. However, 6 July began with a Central Front counterattack. Rokossovsky, while completing the reinforcement of his defences, which included two rifle corps and the 2nd Tank Army, unleashed 16th Tank Corps. Directed against the 20th Panzer Division in the area of the greatest German penetration, 100 T-34s and T-70s struck at 0130 hours. Within four hours, the thrust – which had been strengthened by 17th Guards Rifle Division – had developed into a major confrontation between Soborovka and Samodurovka. Taking advantage of the greater freedom over the battlefield that came with the mounting calls on the Luftwaffe’s rapidly diminishing resources, the reinforced Red Air Force flew in close support. General Rudenko later explained:

I decided to change the tactics of the strike aircraft. I concluded that it would be more expedient to deal one devastating strike against a large force of enemy troops, so for this end I decided to dispatch our aircraft in massive strength. The idea also was that this massing of our aircraft would suppress the enemy’s air defence and thus reduce our own losses.

Il-2s arrived in squadrons of eight and, having circled over the panzers and selected a target, took it in turns to dive down. They aimed at the rear end of their targets with bombs, rockets and cannon. Although it was beyond the Red Air Force to win air supremacy immediately, on just the second day of Zitadelle, it began to out-muscle the Luftwaffe, which gradually lost its aerial dominance. Although the Soviet air arm was not destined to be ‘the decisive battle-winning instrument its numbers would suggest it should have become’, Rudenko commented on the strikes that morning:

The impact of their attack was powerful and obviously unexpected by the enemy. Smoke piles rose from his positions – one, two, three, five, ten, fifteen. It emerged from burning Tigers and Panthers. Despite the danger, our soldiers jumped out of the entrenchments, threw their helmets into the air and shouted, ‘Hurrah!’

Although Rokossovsky’s counterattack had run out of steam by midmorning, it had successfully pre-empted Model’s own thrust and allowed the Central Front time to conclude its defensive preparations. As German and Soviet aircraft continued to tangle overhead, General Lemelsen’s XLVII Panzer Corps mounted an assault led by 300 tanks. To the right, pushing on towards Samodurovka, the 20th Panzer Division had now been joined in the offensive by two of the corps’ reserve formations. On the opposite flank, the 9th Panzer Division advanced towards Ponyri Station, while in the centre, the 2nd Panzer Division, led by the 505th Heavy Tank Battalion’s 24 serviceable Tigers, probed towards Olkhovatka against one of the most strongly fortified sections of the main defensive belt. The rumble of hundreds of guns mixed with the shriek of Katyusha and Nebelwerfer batteries in a shocking display of firepower. The battlefield erupted as bombs, shells, rockets and mortars exploded, each with a blinding flash, creating fountains of soil and palls of smoke. Tanks opened fire on enemy machines as the advancing infantry, denied any help across the featureless battlefield, was met by a hail of fire. ‘It was Armageddon,’ recalls one German survivor:

Every second that passed I expected to be my last. Men were falling around me but we just focused on our objective. Our officer was killed in an explosion, my section commander was shot through the neck shortly after . . . Soviet aircraft added to the hell as they appeared through the smoke without warning as we could not hear their engines over the noise of battle. They strafed us time after time, hour after hour . . . Death would have been a merciful release from that hell, but I came through. Those were the worst moments of my war, of my life. I am haunted by memories of it. Absolutely terrifying.

Gradually the two sides closed. Marc Doerr used his machine gun to suppress Soviet positions. ‘I took up a position on the lip of a shell crater and concentrated my fire on a trench approximately 600 yards away where I could see movements . . . As the attack progressed I eventually moved into that trench and found it full of enemy dead. I believe that the Soviets called the MG-42 the Hitler Saw after the noise that it made. It was a fearsome weapon with a tremendous weight of fire.’

The panzers had destroyed numerous T-34s at long range, and then endeavoured to finish off the remaining tanks as the T-34s darted to within a couple of hundred yards of the German formations. The T-34s were pushed to their limits, engines roaring, and as the morning grew warmer, temperatures inside the cabins rose to excruciating levels. The perspiration dripped off the crews’ noses and stung their red-rimmed eyes. Every time the main armaments were fired, the compartment filled with choking, blue-grey cordite fumes. Vladimir Severinov has said:

There was a lethal cocktail of vapours in a T-34 during battle. We once had a loader and then a driver pass out during action, which sent us into a panic as the tank was designed to advance when the throttle pedal was raised, not when it was lowered. We opened the hatch to let the worst of the foul air out and within a few moments the driver was aware enough to apply the brake. We were desperate to get out into the fresh air, but we could hear the rounds splatting against our armour and knew that we would be dead within seconds . . . Being in a tank in July 1943 was like being placed in a hot oven pumped full of toxins and suffocated.

Attacking units disappeared into a cloud of explosions and smoke never to be seen again. The Soviet second line ate up the Wehrmacht’s young men hour after hour – but the divisions’ commanders continued to hammer away. Infiltrations were made and snuffed out, assaults were mounted and crushed. Armour ran into minefields or fell pray to the anti-tank guns and tank-killer teams. Radios were alive with orders, and pleas for information about the progress of reinforcements and supplies. The Soviets hit back with local counterattacks, which sometimes stunned the Germans with their size and ferocity. At 1830 hours, for example, 150 tanks of the 19th Tank Corps struck the 20th and 2nd Panzer Divisions with such force that some regiments were sent reeling. Herbert Forman has testified:

The tanks came out of nowhere. Just as we were beginning to make a little progress. They clattered into us and made a mess of the positions that we had carved at such great expense. Within an hour our own armour had stopped the advance, but the battle continued until darkness and we were left back where we had started from that morning.

In this way, the offensive power of the Tigers was finally broken and the remaining six machines of the 505th Heavy Tank Battalion were withdrawn as the unit underwent a major overhaul and reorganization. Model’s mailed fist, such as it was, had been denied its talisman.

XLVII Panzer Corps had been starved of its ability to manoeuvre and drawn into a cleverly executed slogging match by the enemy. Nowhere was this more apparent than at Ponyri Station, which was to develop into an encounter that became known to the troops as a ‘mini-Stalingrad’. The village of Ponyri nestled in a balka a couple of miles to the west of Ponyri Station, which was a more substantial conurbation that had grown up around the local railway station. With its cluster of warehouses and sturdy buildings, the town, although small, was one of the largest in the area, and it controlled the roads and railways leading south. Its seizure was seen by Model as a means of breaching the Soviets’ second line, rolling it up through Olkhovatka and opening a route to Kursk. Recognizing its importance, the 13th Army was determined to hold on to it at all costs. What resulted, therefore, was a fraught and bloody confrontation to which both sides committed copious resources over several days.

The Germans had already taken the northern part of Ponyri Station on the first day of Zitadelle, and at first light on 6 July, 292nd Infantry Division resumed its assault, supported by elements of the 9th Panzer Division on its right flank. Preceded by a heavy artillery bombardment and Stuka dive bombing, which reduced much of Major-General M.A. Enshin’s 307th Rifle Division defences to rubble, the formations attacked. But the Germans stalled as they tried to pick their way through a protective minefield and over barbed-wire obstacles. These were covered by machine-gun nests and mortars, and the Soviet guns opened up. The Wehrmacht’s attack was immediately stripped of its shape and stuttered forward with heavy losses. Some units managed to break into the town, but became entangled in a network of mutually supportive positions in streets of fortified houses. When the armour followed, they soon became aware of carefully positioned anti-tank guns, which quickly converted the unwary and unlucky into blazing wrecks that blocked the thoroughfares. The infantry endeavoured to clear buildings as they progressed southwards, but where successful they were soon overwhelmed by counterattacks. The Soviets seemed to glory in vicious hand-to-hand fighting.

A simultaneous attack was made to the east of Ponyri Station where the 86th and 78th Infantry Divisions sought to take Hill 253.5 and Prilepy. These positions would not only give the Germans an opportunity to undermine Ponyri’s defences but also offered a means of outflanking the tenacious resistance of Maloarkhangelsk. Nikolai Litvin’s battery was one of those that lay in wait for just such a move. They were situated in a field of uncut rye between two parallel ravines, which was deemed a likely area for a panzer attack. Having camouflaged their guns and established fields of fire, the gun crews prepared themselves for an onslaught. ‘The morning of 6 July dawned cloudy, with a low, overcast sky that hindered the operations of our airforce,’ the inexperienced Litvin says:

At around 6:00 a.m., our position was attacked head-on by a group of approximately 200 submachine gunners and four German tanks, most likely PzKw IVs. The tanks led the way, followed closely by the infantry. The Germans were attempting to find a weak spot in our lines . . . but they didn’t seem to see us. We felt a gnawing fear in the pit of our bellies as the German tanks rumbled toward us, stopping every fifty to seventy metres to scan our lines and fire a round . . . My knees and legs began to tremble wildly, until we received the command to swing into action and prepare to fire. The shaking stopped, and we became possessed by the overriding desire not to miss our targets.

The guns were ordered to fire when the enemy had reached within 300 yards of the line. Litvin continues:

Our Number One gun set a tank ablaze with its first shot, and then managed to knock out a second tank. The combined fire of our Number Three and Number Four guns knocked out a third German tank. The fourth tank managed to escape . . . [My gun] opened up on the advancing infantry with fragmentation shells. The German submachine gunners stubbornly continued to push forward. As they drew closer, we switched to shrapnel shells and resumed fire on them. Not less than half the Germans fell to the ground, and the remaining drew back to their line of departure.

A temporary lull followed during which the Soviet gunners breakfasted and celebrated their success with 100 grams of vodka, but a new push was heralded by a Stuka attack. These bombers were called ‘musicians’ by the Red Army due to their air sirens, which wailed as they dived on their targets. The first bomb exploded some 60 yards from Litvin’s position. Another fell directly above his dug-out:

I saw my own unavoidable death approaching, but I could do nothing to save myself: there was not enough time. It would take me five to six seconds to reach a different shelter, but the bomb had been released close to the ground, and needed only one or two seconds to reach the earth – and me. During those brief seconds as I watched the bomb fall, my entire conscious life flashed through my mind. Everything seemed to happen in slow motion. I badly didn’t want to die at the age of twenty . . . Just before the bomb struck, I rolled over face down in my little trench and covered my face with the palms of my hands . . . I heard the bomb explode. There was a repulsive smell of TNT, and I felt two strong blows to my head. It seemed to me that my head must have been torn off . . . The bomb had exploded very close to my trench, and I was buried in loose dirt.

Pulled unconscious from his entombment, it took three days for Litvin’s hearing to return and another week before he could speak.

Subsequent pushes by the Germans did take ground but there was no breakthrough and Ponyri remained a hornet’s nest in Soviet hands. As Zhukov later wrote: ‘All day the roar of battle on the ground and in the air engulfed the area. Although the enemy kept pouring new tank units into the battle, here again he was unable to achieve a breakthrough.’ On the flanks of the Ninth Army’s front, meanwhile, neither XXIII Corps nor XLVI Panzer Corps could develop their modest first-day territorial gains in any meaningful way and failed to do so for the remainder of Zitadelle. As dusk fell on the 6th, therefore, Rokossovsky had been handed an opportunity to concentrate his defences against the centre of the line. With XLVII and XLI Panzer Corps still flailing through the 13th Army’s main defensive line, the Central Front could feel content that they had managed to take the sting out of Model’s initial blow. They had to remain wary of his reserves, though, and could not afford to relinquish possession of the Olkhovatka heights if they were to wear the Ninth Army down. By taking formations from the quieter areas of his Front – the 70th Army released one division and the 65th Army two tank regiments – Rokossovsky successfully managed to reinforce his defences with a minimum of disruption.

Even as the Central Front took steps to enhance their resistance, Model underwrote plans for his XLVII and XLI Panzer Corps to continue their frontal attacks on the Olkhovatka line. Like so many generals in similar situations down the centuries, when confronted with defences that were expected to break open at any moment, he felt compelled to throw more resources at them to complete the job. If, instead, Model had decided to concentrate his attack elsewhere, he would not only lose whatever momentum had been accrued but might also miss the opportunity to finish off a defence that was on the verge of collapse. Thus, on 7 and 8 July, the Ninth Army continued to pummel away at Olkhovatka’s defences for, in the words of one German observer, ‘here was the key to the door of Kursk,’ which could be seen 400 feet below. Model was convinced he could draw Rokossovsky’s armour and defeat it on unfavourable ground. The fight for this part of the line, therefore, was never going to be anything other than a protracted brawl – the destruction of Soviet reinforcements was all part of the Ninth Army’s plan.

Thus, on the morning of the 7th, XLVII and XLI Panzer Corps pushed forward once more. The attack was to take the form of three mutually supportive but distinct movements: one by the 20th Panzer Division towards the village of Teploe, the second by the 2nd Panzer Division (supported by the briefly rested Tigers of the 505th Heavy Tank Battalion) focusing on Olkhovatka, and the third into and around Ponyri by the 18th Panzer Division (released from the reserve), the 292nd and the 86th Infantry Divisions, supported by the 9th Panzer Division. The 6th Infantry Division was to continue plugging away in the middle of the line and provide a bridge linking the 2nd and 9th Panzer Divisions.

There was little finesse to Model’s plan, which simply seemed to reflect the wider German desire to use brute force to smash holes in the enemy’s positions. The application of the Ninth Army’s force was, however, enhanced on 7 July by the temporary loan of over 500 aircraft from Luftflotte 4. He-111s and Ju-88s appeared over the battle lines at first light to soften the Soviets’ defences, and were followed by Stukas operating just in front of the advancing panzers. As the ground formations once again became locked in combat, the Red Air Force sought to neutralize the Luftwaffe by smothering the front with aircraft. Although their losses were heavy – Stalin’s pilots remained less capable than their rivals – the Soviets did succeed in denying the Luftwaffe freedom of movement in the skies above the battlefield. Indeed, as the Red Air Force’s sorties increased and the Germans’ declined for want of petrol, oil and lubricants and serviceable air - frames, it was the Soviets who achieved general and local air superiority over the Central Front, and this situation persisted throughout the rest of the operation. General der Flieger Friedrich Kless, Chief of Staff of Luftflotte 6, said:

By 7–8 July the Soviets were able to keep strong formations in the air around the clock . . . Unremitting air actions of extended duration necessarily caused the technical serviceability of our formations to decrease, therefore making it unavoidable that the quantitative Soviet superiority should temporarily be in a position to act directly against German troops during temporal and spatial gaps in the Luftwaffe fighter coverage . . . Russian air attacks began to hit the important supply roads of our spearhead divisions to an increasing extent, with raids striking points as far as [15 miles] behind German lines.

Often lacking the support of air artillery, upon which they had come to depend, the panzer formations felt vulnerable. Without the ground-based firepower, or boots on the ground to make up for this deficit, casualties mounted. Detailing the 20th Panzer Division’s attack on Samodurovka, Paul Carell has written:

Lieutenant Hänsch rallied his small handful of men: ‘Let’s go, men, one more trench!’ The machine-gun rattled. A flamethrower hissed ahead of them. Two assault guns were giving them fire cover. They succeeded. But the lieutenant lay dead, twenty paces in front of his objective, and around him, dead and wounded, lay half his company.

Within an hour of closing with the enemy, all the officers of the 5th Company, 112th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, had become casualties. Other units suffered similar fates and with their attacks withering, some were forced to withdraw. Others, however, forged on and, in a series of local battles, managed to avoid the minefields, prise the Soviets from their trenches, overwhelm the anti-tank guns and perforate the defences. By noon, a two-mile gap had been created between the villages of Samodurovka and Kashara through which poured the Tigers followed by the 2nd and 20th Panzer Divisions. It was a critical moment in the battle for with the 6th Guards Rifle Division’s left flank crumbling, XLVII Panzer Corps had gained a position from which they could make a direct assault on the Olkhovatka heights.

The situation had, however, been anticipated, and the Soviets were well placed to deal with it with the minimum of fuss. The 17th Guards Rifle Corps, supported by the 13th Army, had already acted to ensure that the ridge was well protected. Having surmounted one line of obstacles, the panzer divisions would have to do the same again if they wanted to gain the ridge. From their observation posts, the Soviet commanders peered through their field glasses at a scene of unremitting carnage as the tiring German thrust was subjected to the close attention of the Red Air Force. Valentin Lebedev, an infantry company commander, recalls:

We could see the tanks assembling for an attack when they were attacked by Yaks and Il-2s. They were sitting targets and despite the best efforts of their anti-aircraft teams, wave after wave of aircraft flew in and did a great deal of damage. After about half an hour, it seemed as if the entire German army had caught fire. Unfortunately, that was not the case.

The Yak 9Ts, sporting 37mm cannon, and the Il-2s, carrying the new PTAB hollow-charge bomblets (which were being used for the first time), were well armed for their mission. The cannon were capable of ripping through 30mm of armour while the bomblets could penetrate 60mm. The turrets of the Panzer IIIs and IVs were just 10mm thick. Constantly moving to provide more difficult targets for the Soviet pilots to hit, the panzers were in poor order when the aircraft suddenly disappeared and dozens of T-34s were already at close range.

Feldwebel Günther Krause’s Tiger took a round in its relatively lightly armoured flank, which set fire to the engine and badly wounded the loader. Krause wasted no time in ordering the crew to bail out and the loader’s limp body was unceremoniously hauled out of the turret hatch as the tank continued to attract incoming small-arms fire. Throwing themselves into a ditch, the five men were then faced with the approach of enemy infantry, who had seen what had happened and were intent on denying the Wehrmacht the services of an experienced crew. Taking up their MP-40 sub-machine-guns and firing at the infantrymen in short bursts, Krause and his driver provided covering fire while the still unconscious loader was carried to the relative safety of a nearby copse. Once their three colleagues had successfully reached the trees, the two men joined them. As they did so, three Tigers came into view to rescue them – two occupied the enemy; the third rolled up by the patch of trees and took them on board.

The German attack on the Olkhovatka heights had been stopped before it even started. By dislocating the two panzer divisions with the airforce and following up with a well-timed counterattack, the Soviets had managed to maintain the integrity of the high ground for another day. Model had little more success at Ponyri. The 6th Infantry Division managed to take the village of Bitiug and the 9th Panzer Division advanced to Berezovyi Log, but overall the attack by the three divisions of XLI Panzer Corps on Ponyri failed to make much of an impression. Despite the additional firepower offered by the 18th Panzer Division, the 307th Rifle Division continued to hold out. Some parts of the town changed hands several times throughout the day but, critically, the Germans were deprived of the opportunity to make a concerted assault with a concentration of armoured vehicles by successful Soviet efforts to splinter their attempted drives. Assisted by battle debris, which included numerous burnt-out vehicles, the Soviets fought back. Tanks were dispatched by mines, guns and Molotov cocktails; the infantry were immobilized by field artillery, mortars and interlocking machine-gun fire. Any groups of Germans who did manage a degree of penetration into Soviet-held territory were ruthlessly hunted down by sections armed with sub-machine-guns, bombs and combat knives. There was little time for the combatants fighting in this arena to rest as the struggle played out within the narrow confines of Ponyri and its immediate surroundings. Assault after assault was launched into the town, and assault after assault was fended off as Rokossovsky flooded the area with guns. The unrelenting nature of the confrontation at Ponyri would never be forgotten by its participants on either side. For some the pressure was too much. Interviewing men who had fought in the battle weeks later, Vasily Grossman noted: ‘Stories about 45mm cannons firing at [Tiger] tanks. Shells hit them, but bounced off like peas. There have been cases where artillerists went insane after seeing this.’