Prologue

I walk in the dusty tracks of the Wehrmacht’s most powerful division under a scorching sun. The flat landscape is pregnant with ripe crops wavering gently in a tender breeze. There are no hedgerows, buildings or people. An unseen road springs from the village of Butovo, but I hear no traffic. There is an intense silence, which helps me to imagine the battle fought here in July 1943. This place is remote. Kursk is 65 miles to the north and Belgorod 30 miles to the southeast. This open steppe land is unlike anything in England and like nothing I have seen elsewhere in Europe. It reminds me most of the American mid-west and feels a long way from home. I look at the sketch map that has been provided for me to help pick out the landmarks. The village of Cherkasskoe lies shimmering a couple of miles to my left, a shallow ditch to my right, otherwise there is nothing but massive fields. I continue northwards and arrive at my destination suddenly – the western-most tentacle of a three-mile long balka. The 50 feet wide and 20 feet deep dried river bed was used during the battle to house a headquarters, field kitchen and a small medical aid station. It was a chasm that offered just a little safety as the landscape erupted around it.

I negotiate the balka’s grassy bank and drop down into the cool air at the bottom. I can hear voices and walk towards them to find Mykhailo Petrik and his son, Anton, enjoying a joke. Mykhailo was an infantryman during the Battle of Kursk and had been stationed in a dug-out not far from here during the opening days of the German offensive. We had met for the first time a week before and he had mentioned that he was keen to show his son the old battlefield and invited me to join them. We shook hands. Mykhailo’s were rough from years spent working as a mechanic near Smolensk; his son’s were soft after years spent working as a doctor in London and Moscow. ‘This is where I came to pick up the food for the section the night before the attack,’ Mykhailo explains. ‘It was full of people, full of activity but there was tension in the air. We knew that the Germans would strike soon. It was an anxious time.’

Anton produces a collapsible chair and, declining with a dismissive wave my offer to steady him, Mykhailo slumps into it. He tells us about joining up in Kiev – ‘a crush of people and a forlorn party official taking names’; his training – ‘they tried to starve us to death’; and his eventual deployment at the front during the battle for Moscow in December 1941 – ‘a nightmare spread over weeks’. His memory is good but details are lacking, until he comes to describe his DP light machine gun. ‘It fired a 7.62mm round from a pan magazine perched on top. It was light enough to fire from the hip, but for accuracy we used its bi-pod. It was a good weapon, but of an old design and was prone to overheating. We fired it in short bursts, but had to be careful not to cook it.’ Mykhailo proceeds to run through the parts of the weapon in loving detail and dismantles an imaginary DP on his lap, and then reassembles it while mumbling to himself. He completes his task with a smile, delighted that he can still remember the process. Anton and I applaud and he makes a little seated bow.

We leave the balka for the position that Mykhailo’s platoon occupied on the morning of 5 July. We walk in bursts of a couple of hundred yards to allow our guide to catch his breath. ‘The landscape has changed over the years,’ he says as Anton places a baseball cap on his father’s balding head, ‘but nothing that blocks the memory. It is all still recognizable.’ I ask him how many times he had been back to the battlefield since the end of the war. ‘Just once,’ he replies. ‘I returned in the 1970s with an old comrade who lived in Belgorod and was making a study of the battle. I do not think that he ever finished it. He died many years ago, but the maps that I copied for you are the ones that we drew during that visit. We spent a day wandering around, making sense of the ground and using some information that we collected and some we had been given by others.’ ‘But are you sure of your bearings now, all these years later?’ I ask. ‘Oh, yes,’ Mykhailo shoots back, ‘I spent yesterday out here hunting around.’ I look at Anton who is shaking his head with incredulity and adds with a smile, ‘This is an eighty-six-year-old man who disregards the advice of his physician son and likes to wander off in the middle of nowhere.’

We arrive at the edge of a field around half a mile from the balka, towards Cherkasskoe. ‘Our section was dug in here,’ Mykhailo announces with authority. ‘The Germans came towards us from that direction.’ I had been so engaged in conversation that I had failed to relate the ground to the battle as we walked. I turn and am astounded by the scene that greets me – a broad front of wide-open fields under a huge sky. I immediately imagine a wall of steel and field grey advancing towards us. I turn to Mykhailo and he opens wide his bright blue eyes and nods his head slowly as if to say, ‘Frightening, eh?’ He gives Anton and me a moment to absorb the scene and then fills in the detail. ‘We were targeted by dive bombers, artillery and tanks. There was an awful crescendo. But then it stopped, as the infantry rushed forward, and was replaced by the drilling sound of German machine guns and the explosion of mortars. That was when I was hit.’ His hand moves up to his neck and for the first time I see an old scar. ‘It was the last time that I saw my comrades,’ he says. ‘They were blown away by the enemy.’ He pauses and stares into the distance. ‘Blown away by the Nazis.’ The crops rustle and there is a short silence before Mykhailo declares, ‘It’s time to move on.’

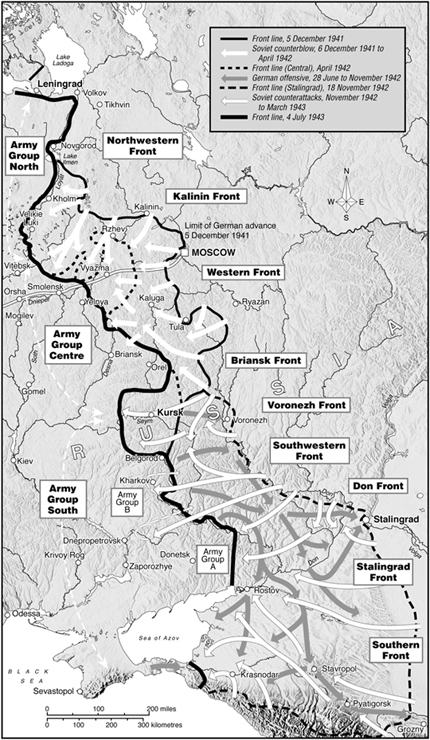

Map 2: The Soviet Counterblows, 1941–3