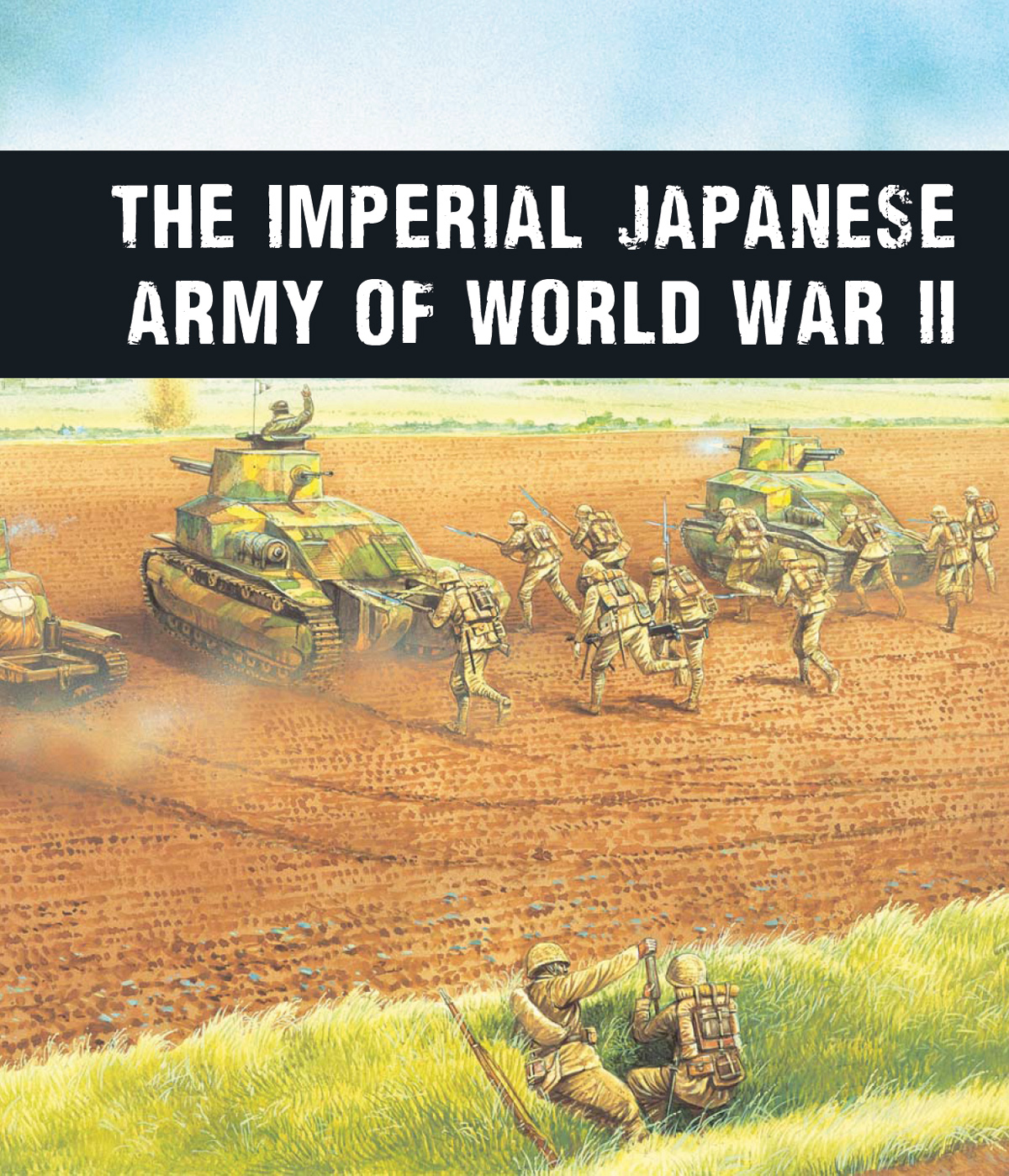

Two Type 89B Yi-Go medium tanks and a Type 94 tankette advance towards the Chinese lines, by Peter Dennis © Osprey Publishing Ltd. Taken from Elite 169: World War II Japanese Tank Tactics.

“I shall run wild considerably for the first six months or a year, but I have utterly no confidence for the second and third years.”

Isoroku Yamamoto

Manchuria had long been a disputed region divided between Russia and China, dominated by local warlords, and falling increasingly under Japanese influence. To the Japanese, Manchuria represented an essential source of raw materials, especially coal. Control of the region was seen to be a necessary precursor to Japan’s plans for a wider Asian war and, in 1931, Japanese troops invaded and established the puppet state of Manchukuo.

After the defeat of the Chinese in Manchuria, sporadic fighting continued between Japanese and Chinese forces in northern China until 1937 – the beginning of what is known in the West as the Second Sino–Japanese War. The Japanese quickly captured Shanghai, followed by the capital: Nanking. The savagery of the fighting and toll of civilian lives were to become notorious and would do much to turn US public opinion against Japan. As many as 300,000 Chinese lost their lives during the ‘Rape of Nanking’ between 1937 and 1939.

By the time World War II began in Europe, Japan and China had been in conflict for eight years. The fighting in China had already reached something of a stalemate by 1939, with rival armies of the Chinese Communists and Nationalists (the Kuomintang, or KMT) putting aside their differences to oppose the Japanese invasion. The Chinese were armed or assisted by various foreign powers including Germany, Russia and America. Japanese and Russian forces clashed on the Manchurian/Mongolian borders in 1939, resulting in the battles of the Khalkhin Gol where the Red Army decisively defeated the Japanese at Nomonhan.

A Type 97 Chi-Ha prepares to ambush the British

The Japanese Army’s humiliating defeat at the hands of the Russians was to have profound effects upon the course of the war both in Europe and Asia. Fearful of facing enemies to east and west, the Russians concluded a non-aggression pact with Germany and collaborated with them in the Partition of Poland. Meanwhile, the Japanese setback undercut the influence of those in the Japanese Army who argued for a strategy of conquest in the north, boosting the authority of those who favoured a strategy based on the south and the Pacific. With the European colonial powers embroiled in war elsewhere, and American metal and oil embargoes choking Japan’s industry, the scarcely defended resources of southern Asia were identified as Japan’s new target. As a result of this change of strategy, the Japanese concluded a non-aggression pact with Russia that would hold until the Russian invasion of Manchuria during the very last days of the war.

The attack upon Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 opened hostilities between the United States and Imperial Japan, and signalled the start of Japan’s conquest of southern Asia. At the same time, the Japanese attacked the Dutch East Indies, the US-controlled Philippines, and the British colonies of Hong Kong and Malaya, resulting in the first major land battle of the campaign against the Indian Army at Kota Bharu. Everywhere, the Japanese were victorious, forcing their enemies into a rapid retreat.

By January 1942, Japanese armies were poised to begin the push through Burma and toward British-controlled India. The Burma campaign would prove to be one of the longest and toughest of the entire war and would absorb a considerable portion of the Japanese fighting strength. On the Allied side, the Burma campaign involved British Commonwealth, Chinese and American armies. The fighting in Burma and subsequent attempted invasion of India took its toll upon the Japanese. From late 1944 the Allies would turn to the offensive, and soon the invaders were in full retreat. A major offensive was launched to capture Rangoon in April 1945 following the battle of Central Burma, but by then the Japanese had already abandoned the city. By the time the Allies were ready to conclude the campaign, events elsewhere were to put an end to the war and all further conflict.

Japanese armed forces saw death in battle differently than their Western opponents. This can be seen in the various terms by which Japanese bulletins refer to soldiers lost in battle.

‘Senbotsu’ is best translated with the term ‘killed in action’. ‘Gyokusai’, however, is a more interesting word, meaning ‘to die gallantly as a jewel shatters’. For the Japanese soldier, this would mean that in a hopeless situation one would rather be killed than surrender.

However, the Japanese culture did not expect a soldier to waste his life in vain. Consequently there is the term ‘tai-atari’ (literally, ‘body crashing’ or ‘ramming one’s vessel into the enemy’). There are countless stories about duty-bound Japanese soldiers who, wounded, would explode a grenade when enemy troops came near, performing a ‘jibaku’ (‘self-destruction while also hurting the enemy’).

In the first six months of 1942 the Japanese invaded New Guinea and took possession of the Solomon Islands lying in a long chain to the east. The region was of strategic importance to Japan’s navy, and control of the region would effectively place Australia under a blockade. This was an intolerable position for the Allies, cutting off communications and supplies, and paving the way for the potential invasion of Australia itself. The Australians fought tenaciously in New Guinea, beating back a Japanese attack at Milne Bay in September and inflicting the first defeat on the Japanese by Allied forces.

While fierce fighting continued in New Guinea, the Americans attacked at Guadalcanal in the Southern Solomon Islands: the first major offensive undertaken by the Allies against the Japanese. Although the Japanese fought with a tenacity that would come to characterise the whole Pacific War, they were eventually defeated and the island fell to US forces in February 1943. Guadalcanal was the first US victory on the ground and the beginning of a long series of amphibious operations or ‘island hopping’ that would lead all the way back to Japan itself.

Japanese forces, Burma (L–R): Corporal, 55th Infantry Division; Private 2nd Class, 214th Infantry Regiment, 55th Infantry Division; Lieutenant, 18th Infantry Division, by Stephen Andrew © Osprey Publishing Ltd. Taken from Men-at-Arms 362: The Japanese Army 1931–45 (1).

The US Marines were to fight a series of amphibious campaigns across the Central Pacific, starting with the assault upon Tarawa to the south of the Marshall Islands. Each island captured provided the US Navy with a base from which to attack the next island, and so on, gradually advancing towards Japan itself. The defenders soon gained a reputation for tenacity in the face of overwhelming odds. The Japanese soldier’s refusal to surrender in the face of defeat forced the Americans to bring overwhelming forces to bear on even the smallest patch of sand and rock.

The battles that raged across the Marshall Islands and the Marianas were hard-fought affairs, but all ended in the same way: with victory for the Americans and virtual annihilation of the Japanese. Typical of such battles was Saipan where fewer than 1,000 of more than 30,000 defenders were taken alive, and more than 20,000 Japanese civilians committed suicide rather than fall into American hands. Faced with such uncompromising fanaticism the Americans responded with massive bombardment from the air and sea.

Semper Fi! US Marines assault the Japanese lines

Following the capture of the Marshall Islands, the Philippines were liberated and US forces drew ever closer to Japan. Major battles were fought at Guam, Iwo Jima and Okinawa. Okinawa was a key stepping-stone that would be used as a base of operations in the projected invasion of the Japanese mainland. For the Japanese it was a last-ditch defence, and was to prove the bloodiest battle of the whole campaign. Japanese casualties amounted to more than 100,000 killed, wounded and captured – the majority dead.

If Japanese forces were to defend their homeland with anything like the fanaticism with which they had defended islands such as Saipan, Iwo Jima and Okinawa, the invasion of Japan would be a bloody affair indeed. Estimates of US military casualties ranged as high as a million men, while the toll amongst Japanese troops and civilians was impossible to predict. All question of invasion was ended with the dropping of two atomic bombs. At the same time, the Russians declared war and invaded Manchuria, rapidly overrunning the by now considerably depleted defenders.

The formal surrender was signed on 2 September 1945 aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo harbour. The War in the Pacific – and with it World War II – was over.

As bad as conventional kamikaze attacks were, the Japanese developed even more dangerous weapons for this form of combat. Fortunately for the Allies, there was too little time to develop and mass-produce these specialized weapons before the war ended.

One weapon that did get into production was the MXY-7 Okha (‘Cherry Blossom’). The Okha was made of wood and consisted of a 2,600–pound warhead, a cockpit and very simple controls. It was a small, rocket-powered aircraft that was usually carried underneath a ‘Betty’ bomber to within 37km of its target. On release, the pilot would first glide towards his target, then ignite one or all three of the Okha’s rockets. It could strike an enemy formation at more than 500 (600 in a dive) miles per hour. This made it almost impossible for interceptors or anti-aircraft guns to stop it.

All in all, more than 850 Ohkas were produced. Fortunately, the ill-trained pilots had trouble controlling the Okha and only a handful were ever launched.

Battle-weary US Marines prepare to receive a furious Banzai charge