1

HAVE GOOD CHARACTER, DON’T BE ONE

I am aware that a man of real merit is never seen in so favorable a light as seen through the medium of adversity. The clouds that surround him are shades that set off his good qualities.

—ALEXANDER HAMILTON1

Most tombstones are engraved with a name and a date of birth and death, separated by a hyphen. The hyphen is a simple symbol—a mere dash—but it is emblematic of everything that person was as a human being. It represents both what we call one’s “résumé virtues,” the aggregate of the notable events of a life, and one’s “eulogy virtues,” the summation of the manner in which a life was lived—in other words, one’s character. For a little line, it packs a lot of meaning.

And it makes us think. What do you want to be remembered for? What will the hyphen represent when your time has come? How do you want to be remembered—for your résumé virtues, or your eulogy virtues? For what you’ve accomplished on paper, or for who you are as a person, your core attributes?

Most of us instinctively want to be remembered for our qualities of character. They are more about who we are as people, our essences. Our desire to be memorialized for the values we exemplified rather than for our undertakings may well have an evolutionary reason, for these essential values are critical to our ability to succeed. Think of the most successful leaders through history: Aristotle, Joan of Arc, Lincoln, Gandhi, Marie Curie, Martin Luther King, Jr., MacArthur. Some of them were brilliant scientists; others were creative visionaries; still others were masterful at strategic planning. They led huge organizations, built grand businesses, led armies to defeat fascism, or inspired whole movements. Their mastery of their field was important to their success. But it wasn’t the secret to their highly effective leadership. Their skills, grit, resiliency, charisma, courage, and credibility all emanated from one thing: their strength of character. Raw competence and talent are not strong enough to stand on their own; all successful leadership relies on the critical foundation of a strong character.

The latest research underscores the connection between character and leadership. Leaders who are competent in their field but who lack critical positive character traits such as integrity and honesty may be successful over the short run, but will ultimately fail. Sports teams led by unscrupulous coaches may succeed for a season or two, but fail over the long run. Companies led by CEOs that foster a culture of deceptive practices might report strong quarterly gains for a handful of years, but will ultimately collapse. Governments run by leaders who bully their way out of international treaties and global norms may gain a short-term political or economic upper hand, but will soon find themselves weaker and less secure in critical ways.

A CHARACTER CRISIS?

Character—the moral values and habits of an individual—is in the spotlight more now than perhaps at any other point in history. People through the ages have looked to public figures and institutions for examples of strong character to follow and emulate, but it is hard not to feel that this core quality is now under siege. We are daily bombarded both in the news and on social media with apparent failures of character. Politicians of all stripes lie so frequently that some news organizations keep a running tally of their lies and half-truths. Long-standing and well-established corporations cheat customers and investors. Previously highly regarded individuals are found to have engaged in illegal or socially harmful behavior, including sexual assault and harassment. Powerful people, more often men, use their prestige and position to sexually assault, exploit, and harass others (think #MeToo). Athletes are caught using illegal supplements to enhance on-field performance. Soldiers are accused of abusing prisoners or harming civilians on the battlefield. Students cheat on exams to improve their chances of gaining admission to the best schools. A win-at-any-cost attitude seems to prevail across all major social institutions.

In addition to harming individuals, this character crisis causes great harm to our culture at large. When major institutions are led by people who do not embrace positive values, confidence in the institutions they represent erodes. How can you trust the well-being of your child to a church whose priests are accused of assaulting their most vulnerable members? Why call the police if you do not trust them to treat you fairly and with dignity? Why do you have to pay taxes if you don’t trust politicians to spend your money with principle? What about your financial investments? Reports of greed and abuse of customers by large financial institutions make one want to hide cash in a mattress or bury it in the backyard rather than trust a broker to look out for one’s best interests.

Even our schools are not exempt. More and more people homeschool their children in no small part because they fear public schools are failing to instill high character and moral values in their children. In speaking with public school leaders around the globe, positive psychologist Martin Seligman has found keen interest in K–12 institutions in developing explicit, scientifically valid approaches to educate children about character. Dr. Seligman has done just this. In several large-scale studies, he reports that the benefits of character education include a higher sense of well-being and better academic performance. Seligman writes, “From my point of view, improvement in grades is a positive byproduct of positive education. But regardless of its influence on success, more well-being is every young person’s birthright and we now know that it can and should be taught.”2

More evidence comes from Mike Erwin, a former Army officer, who founded a nonprofit organization called The Positivity Project.3 This project provides evidence-based instruction on character development in schools across the United States. Each week, tailored to their age group, students learn about a different character strength and, through interactive exercises, learn how to express this trait in their dealings with others. The Positivity Project has been a smashing success, with so many schools wanting to adopt the program that Erwin has had to scramble to keep up with demand. This hunger for character education in our schools underscores the perception that more needs to be done to set children on the path toward a value-driven life.

A CAUSE FOR HOPE

In psychology’s first century as an independent discipline, the psychology of positive character was largely ignored. Sigmund Freud, a medical doctor, focused on psychological approaches to treating mental disorders. Ivan Pavlov, the Russian physiologist, studied basic principles of learning. B. F. Skinner, the American behaviorist, thought that psychologists should only study overt actions and behaviors of animals and humans. For him, delving into unobservable traits and states was essentially nonscientific. More recently, cognitive psychologists have looked at perception, attention, memory, and decision-making, but haven’t factored character into their conceptions of how people interpret the world and solve problems.

But things are changing. Today, at any meeting of psychologists, you will find character to be a major topic of discussion. The psychological science of character is increasingly sophisticated. Dr. Matthews and his psychology colleagues are actively designing new ways of classifying, measuring, and developing character, building their understanding of the role character plays in leadership and trust, and in overcoming adversity. They are establishing empirical links between character and personal and social resilience. Organizations are taking notice of this connection. Now colleges and universities, along with the military and private corporations, are systematically integrating character assessment and development into how they select, educate, train, and develop their students and employees. Sports teams—both amateur and professional—are seeking the advice of psychologists who specialize in the study of character to help them build and sustain highly competitive teams. Fortune 500 companies, nonprofits, and other organizations are calling in experts to help them understand how to instill a culture of character. In short, rapid advances in the psychological science of character promise to help remedy the character crisis that the nation is now experiencing.

We sense the public’s hunger for a return to core values and high character. The emerging science of character combined with character-based leadership provide hope for a better tomorrow. As you will see in the chapters ahead, character and leadership are directly correlated. This is not limited to the military and CEOs at Fortune 500 companies. We wrote this book because the advantage of strong character and how to foster it should be available to everyone. Gaining the character edge will help you succeed in all aspects of your life. Your bottom line and your relationships will improve. Most important, the world will be a better place.

You are probably asking, What exactly is character? Why does it matter so much to success? Can mine be changed? How? What can I do to show better character? How can I sustain it? How can I develop it in others? Addressing these questions is our mission in The Character Edge. We will teach you about the science of character and also, based on decades of leading others in the most dire of circumstances, the art of nurturing and cultivating character in yourself and others. Character will give you a personal competitive edge, and you may then offer others a model to follow and help everyone thrive.

WHAT IS CHARACTER?

Autumn at West Point is a glorious time. The foliage glows gold and orange against the blue of the Hudson River winding below the hills. The football team is hard at practice getting ready for the next big matchup. Plebes are nervous and full of promise. In West Point’s Thayer Hall, juniors (known as cows in West Point’s lexicon) sit in a classroom in a course required of all cadets, Military Leadership, ready to learn about the value of character. They read a chapter authored by Dr. Matthews on character, what it is, how to assess it, and what it means in leading soldiers in combat. Cadets readily engage in discussion. They want to know more, and the questions fly. Does West Point help me develop character? How? What can I do to strengthen my character? How can I use this self-knowledge to improve my leadership skills? Will my positive character stand up to the adversity of combat and life? This lesson sets the table for a semester of probing character and leadership.

Cadets are challenged to think of the ways we use the word character:

- Lisa is quite a character!

- Wow, that is completely out of character for Jim.

- We want to encourage our children to be of good character.

- He shoplifted because he is a bad character.

What they learn is what we set out to do here in The Character Edge. To understand the idea of character more precisely, to know how to assess it, to learn how to nurture it in ourselves and others, and to develop the skill of using character to achieve desired goals, a formal definition of character is needed.

We define character as “a person acting on his or her world in ways that benefit it and, in turn, the world thereby providing benefits for the person.”4 This definition has three important parts: (1) character involves actual behavior; (2) this behavior has benefits to the world; and (3) these benefits to the world in turn provide benefits to the person. It is not enough to just think the right way about others and the world (although this is laudable)—thoughts and feelings must translate into actions, and these actions must have a positive impact beyond the individual. One might feel sorry for a panhandler one passes on the street, but that same sense of empathy might compel a person of strong character to organize a charity drive to raise funds for blankets and coats for homeless people. Cadets understand the distinction. Many give up spring break to help people in need around the nation and the world, whether helping the homeless in New York City or with hurricane relief in Puerto Rico.

The third part of this definition is often overlooked, but it is the critical piece to convince people—and you readers—that cultivating and maintaining core character is worth your time. It has empirically been proven that exercising positive character traits to do good for others and make the world a better place improves happiness and individual well-being. Scholars agree that character is an attribute of human nature that involves mutually beneficial exchanges between a person and his or her environment or context. Stanford psychologist Bill Damon has spent his career studying moral virtues. He consistently finds that these virtues are linked to life satisfaction. Damon reports, “People who pursue noble purposes are filled with joy, despite the constant sacrifices they feel called upon to make.”5 It is a case of “you scratch my back, and I will scratch yours.” But this “back-scratching” involves genuinely beneficial actions.

Another feature of character is consistency over place and time. At West Point, it is not good enough to be honest in the classroom if you then lie to others about your accomplishments or actions outside the classroom. A cadet can’t live honorably at West Point and abandon his or her values after leaving the academy grounds. And, importantly, character plays out over time. As you will discover in the pages ahead, research overwhelmingly shows that character is learned like other behaviors and attributes and, if mindfully attended to, may grow as we mature. We recognize this at West Point, where more discretion is given to plebes (who would be called freshman at other universities) who violate the honor code than is given to firsties (called seniors at other colleges), who have had more time to learn and internalize these values. Living honorably is to have these values become part of our essence, so that if we are faced with a compromising situation, we do not have to think about what is right or wrong—our natural reaction is the manifestation of these internalized principles.

Another way to consider this is to picture yourself holding a cup of coffee filled to the top when someone accidently bumps into your arm. What is in that cup is going to spill out whether you want it to or not. What spills out is the essence of what was inside. Say someone cuts you off while you are driving. Do you swear and blare your horn? Or do you take a deep breath and be grateful that neither of you were harmed? When a colleague gleefully gossips to you about another colleague’s home troubles, do you find yourself contributing to the gossip or do you step away, suggesting that the person’s home life is likely difficult and definitely none of your business? When you discover a mistake on an invoice and find a client has overpaid your company, do you look the other way and deposit the check, or do you email the client to rectify the problem? In the myriad of unexpected situations confronting us daily, we find ourselves instinctively reacting. Our actions are the true manifestation of the values we have internalized. If we actively and consistently develop our character over time, our actions in all situations will be consistent with the values of our character.

So, in part, strengthening one’s character involves doing good things that benefit others, which therefore brings benefits to oneself, and doing it consistently over time and place. This is a necessary condition for the establishment of trust. In our experience, trust is the most important aspect in being an effective leader. We as humans naturally and through socialization have a sense of what good character means. The scientific study of character shows that where you live, your culture, your ethnicity, your nationality, have little bearing on character. People throughout the world share a common view of what constitutes positive character and virtue. Different cultures may emphasize or value certain character attributes more than others, but there is consensus on what right character looks like.

A CLASSIFICATION OF CHARACTER STRENGTHS

We can all think of strengths of character. Who doesn’t know the apocryphal story of George Washington and the cherry tree? But what exactly are the traits that count? Are they the same for everyone, or do values depend on the culture in which one is raised? Modern psychology provides us with a more comprehensive way of classifying and understanding the full range of positive character strengths. The broadest and most useful classification of these strengths was first proposed in 2004 by two founders of positive psychology—Dr. Christopher Peterson of the University of Michigan and Dr. Martin Seligman of the University of Pennsylvania.6 Together, they studied everything that psychologists and other social scientists had learned about character over the past hundred years. They also studied the world’s major religions and the writings of philosophers from around the globe, beginning with Aristotle up to contemporary times. Seligman and Peterson identified twenty-four character strengths that are common in the human species. These twenty-four character strengths are universal and not dependent on specific cultures. Honesty, it turns out, is valued by all people in all cultures. Not all individuals are honest (far from it, unfortunately), but across the planet the trait is treasured and considered a hallmark of a virtuous life.

Seligman and Peterson’s ideas spawned thousands of studies of character. A study of more than twelve thousand adults in the United States and Germany revealed that the character strengths of love, hope, curiosity, zest, and (particularly) gratitude were linked to high life satisfaction.7 In parents of children with cancer, the parents who are higher in optimism do a better job of coping with the challenges of dealing with their child’s disease than do pessimistic parents.8 In another study, Dr. Matthews investigated the impact of character among US Army combat commanders. One commander had endured several of his soldiers killed in combat action. Another commander’s wife announced to him, halfway through his combat tour, that she was divorcing him. Yet another worked for an unethical commander who allowed graft and corruption in his battalion. Matthews found that, whatever the challenge, certain strengths of character were called upon to deal with the adversities. These officers most frequently turned to five specific strengths described by Peterson and Seligman to cope with such tough situations: teamwork, bravery, capacity to love, persistence, and integrity.9

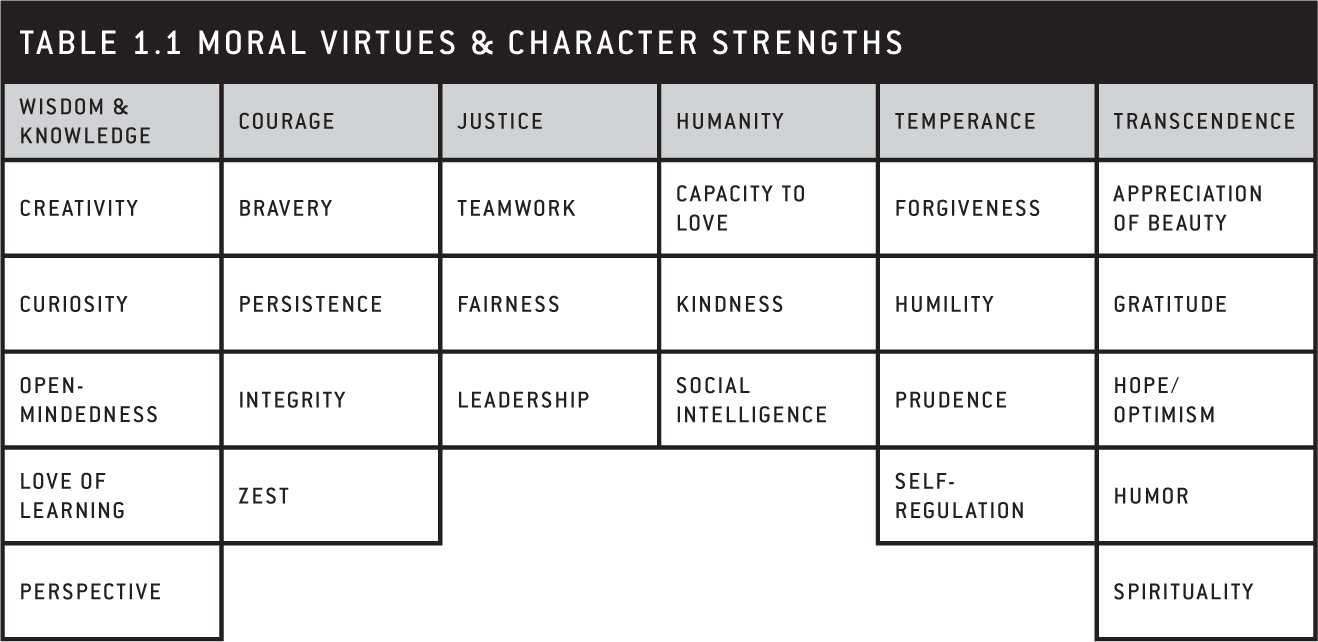

Seligman and Peterson classify these twenty-four character strengths into six overarching categories called moral virtues. These six moral virtues, with their associated character strengths, are:

• wisdom and knowledge (creativity, curiosity, open-mindedness, love of learning, perspective)

• courage (bravery, persistence, integrity, zest)

• justice (teamwork, fairness, leadership)

• humanity (capacity to love, kindness, social intelligence)

• temperance (forgiveness, humility, prudence, self-regulation)

• transcendence (appreciation of beauty, gratitude, hope/optimism, humor, and spirituality)

We each have a unique profile of character strengths. This helps define who we are as individuals. Artists may find that their top character strengths cluster in the moral virtue of transcendence. A soldier may be particularly strong in the moral virtue of courage. Frequently, our highest strengths are scattered across the six moral virtues. A professor needs to embrace and display love of learning and curiosity in her role as a teacher and scholar. But in her role as a family member and parent, strengths of humanity such as capacity to love and kindness are important. A full, well-lived life is enhanced by having strengths from across the moral virtues.

WHAT ARE MY CHARACTER STRENGTHS?

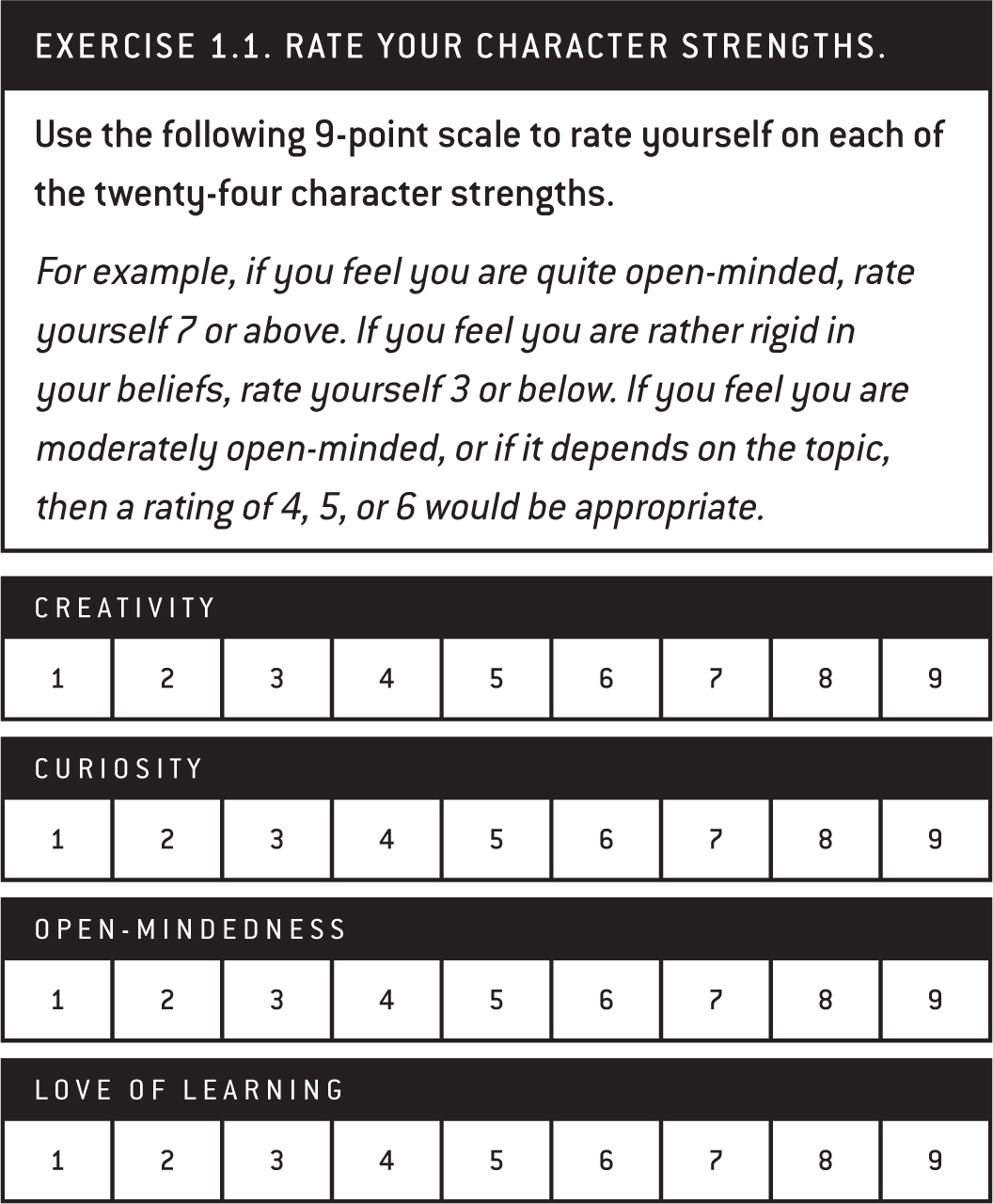

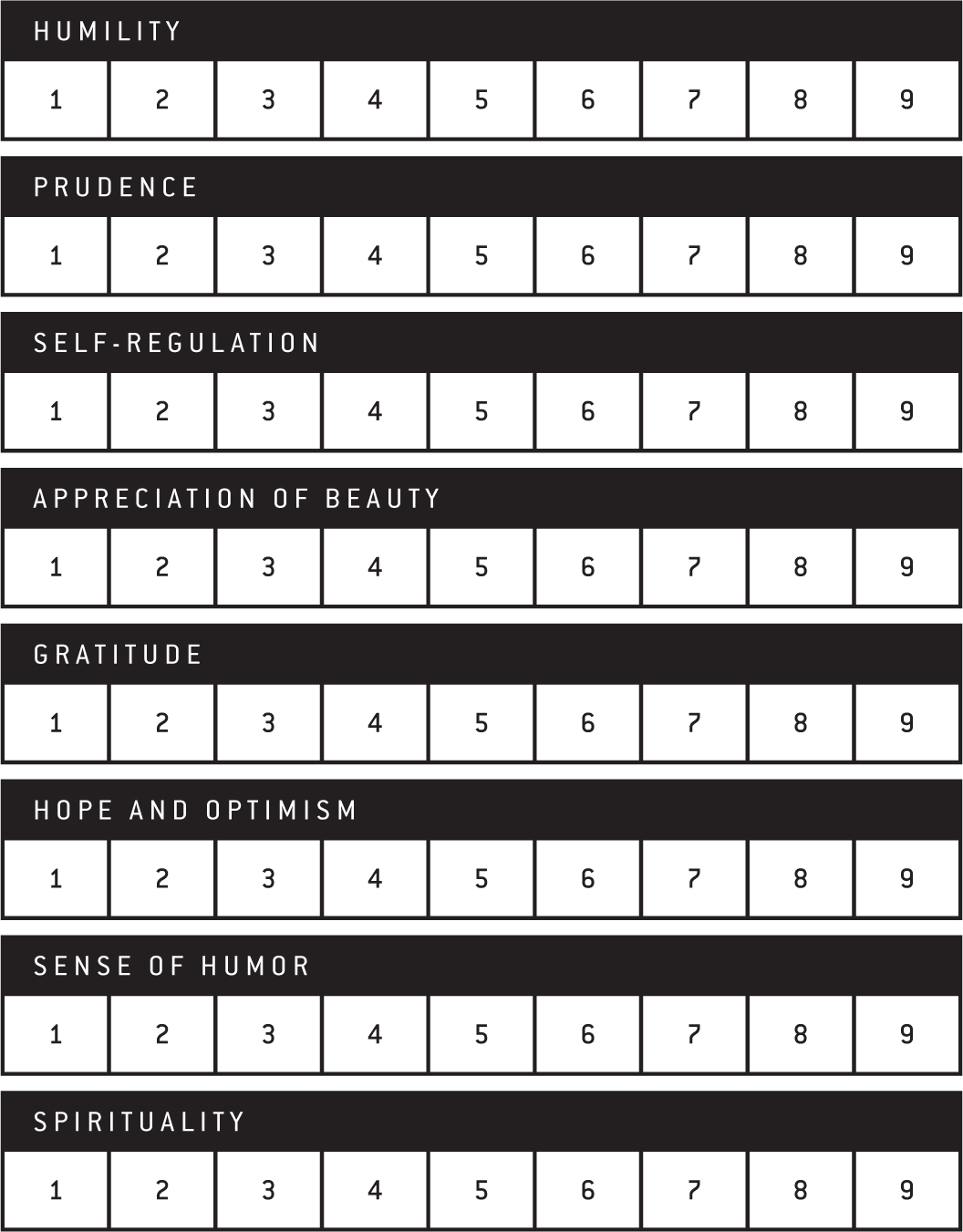

Now it is time to learn about your own character strengths. It turns out we are pretty good at recognizing our strengths of character, especially if given a set of questions to consider. For a quick assessment of your twenty-four character strengths, complete Exercise 1.1.

To determine your highest character strengths, simply note which of the twenty-four strengths have the highest numbers. Look for your six or seven highest strengths. There may be some ties; that is okay. Then, to see how your strengths are distributed across the six moral virtues, circle your highest character strengths in Table 1.1.

The nice thing about character strengths is that they are all good. Think about how you use your top strengths in the many roles you play in your daily life, both at home, work, or school, and with your family, friends, colleagues, and others.

Peterson and Seligman provide a more systematic way of assessing character strengths—the Values-in-Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS). The VIA-IS consists of multiple questions that tap into each character strength and provide insight into one’s personal, unique profile of strengths. The VIA-IS is available online at no charge. Go to www.authentichappiness.org, register, and then look at the menu for the VIA-IS. Complete the test. You can request different types of feedback. We suggest that you ask for a rank ordering, from highest to lowest, of your character strengths.

How did you come out? Again, keep in mind there are no bad character strengths. Peterson and Seligman believe it is particularly instructive to look at your top five or six strengths, which they refer to as signature strengths. By this, they mean the character strengths that are not only your highest, but are also the ones that you may find the easiest to use to achieve goals, respond to setbacks, excel at school or work, or enhance personal and social well-being. You may also find it insightful to see if your signature strengths tend to group within one or two of the moral virtues or are scattered across all six.

It may also be instructive to look at your lowest character strengths. Don’t be dismayed if a character trait you value falls relatively lower on your hierarchy of strengths. Remember, this is a rank ordering. Even if all of your strengths, compared to those of other people, are relatively high, your rank ordering of strengths will still produce some at the bottom. A strength you value, such as spirituality, could appear low on your hierarchy but still be strong overall when compared to that of other people.

When thinking about your profile of character strengths, also keep in mind that we intuitively turn to specific strengths of character depending on the situation in which we find ourselves. Perhaps spirituality is not one of your signature strengths, but at certain times and in certain situations in your life, spirituality may be of overarching importance. (An axiom of combat: “There are no atheists in foxholes.”) Being a successful and well-adjusted person not only requires knowing your character strengths, but also matching them to the different challenges we all face in life’s journey. Think of your strengths as being a toolbox. The goal is to learn to match the right strength to the right job.

GROWING CHARACTER

You now have a better idea of your character strengths. What use is this information? A major theme of this book is that character can be nurtured and grown. We are not stuck with whatever character we currently have. We see this at West Point, where the academic, military, and physical-fitness curriculum is explicitly designed to allow cadets to learn about their character, and to hone the attributes of character necessary to lead soldiers in combat. Parents know that they have a huge influence on the character development of their children. Schools from kindergarten through the twelfth grade recognize “citizenship” and character as vital parts of a complete education. Both science and practice agree that the actions of leaders, parents, and teachers are vital in character development. And character does not display itself in a vacuum. The culture of the organization you are in plays a significant role in whether you reliably display positive character. In later chapters we will take a close look at how a variety of organizations including West Point may impact both the development and display of positive character.

CHARACTER, CULTURE, AND LEADERSHIP

You can alter your character. But it is not just something inside you; it is influenced by the culture around you. The culture of a military unit, a school, a workplace, or any other organization is critical to its growth, values, morale, learning, development, and mission success. The person responsible for that culture is the commander, the principal, the CEO, or the leader.

Trusted Army leaders, such as Lieutenant Colonel Derby, described in the preface, are first and foremost competent at their jobs. They know strategy, tactics, and procedures and demonstrate general combat expertise. But that is not enough to lead effectively in combat. Effective leaders are also of high character. They are honest and courageous and of high integrity. But even this is not enough. They have to be perceived as having a true interest in their soldiers’ well-being. These leaders put the needs and welfare of their soldiers far above their own needs for personal glory or promotion. And putting soldiers first has to be genuine; if not, it is quickly discovered.

Sadly, some leaders fail in this regard. We learned the story of the battalion commander who, although technically competent, failed in character and therefore failed in trust and leadership. Most soldiers would prefer a leader with average competence who exemplified high character and cared for his or her troops over a highly competent commander who did not possess high character and caring. Character and caring may be less tangible than competence, but they are just as vital to effective trusted leadership.

Think about leaders in your personal experience, including workplace managers, coaches, or teachers. You don’t have to be a combat soldier to need a leader who is competent, of high character, and who cares about you. The coach who knows all of the X’s and Y’s but fails in integrity will fail both as a leader and in leading his or her team to consistent success. The police lieutenant who is competent and of high integrity, but puts his or her career ahead of those he or she leads, will never be fully trusted or respected. The boss who assumes credit for your idea in a meeting with the company head cannot ever hold your trust or respect.

ORGANIZATIONS CAN AND MUST SET THE STANDARD

In his book Black Hearts, Jim Frederick describes the actions of First Platoon, Bravo Company, First Battalion, 502nd Infantry Regiment. Deployed to Iraq in late 2005, without enough soldiers and equipment, the regiment was assigned to the so-called Triangle of Death south of Baghdad.10 Undermanned and stationed in outposts subject to near-daily enemy fire, with heavy casualties, the soldiers were poorly fed, sleep-deprived, and constantly dealing with the death or wounding of their comrades.

These soldiers rarely felt safe and secure from the enemy. Isolated from higher headquarters, First Platoon soon established unique norms and ways of doing things, and these did not reflect the standards of conduct and discipline expected of Army soldiers. On March 12, 2006, four First Platoon soldiers exacted revenge for their hardships on a local Iraqi family. Fueled by anger and frustration, and enabled by a questionable command climate, these soldiers brutally raped a fourteen-year-old girl, before murdering her and setting her body on fire. They also murdered her parents and her sixteen-year-old sister. Ultimately, five soldiers were charged and either found guilty or pleaded guilty to charges stemming from this incident. Charges against a sixth soldier were dropped in exchange for his testimony, and he accepted an administrative discharge from the Army.

The Black Hearts story illustrates an extreme example of what can go wrong when leaders fail to adequately monitor, embrace, and reinforce positive values and character among their members. Many other examples come from athletics, education, politics, and the corporate world. Positive character must be a focus for leaders in all organizations. Equally important, the organization itself must have a clear values statement and provide explicit structure and support that promotes and rewards positive character. The Army, for example, formally embraces seven values necessary to fight and win wars. Leaders and soldiers are constantly reminded of these seven values, through formal training and by artifacts such as key chains or posters listing these values. The seven Army values are loyalty, duty, respect, selfless service, honor, integrity, and personal courage. Had these values been emphasized and practiced by those involved in the Black Hearts incident, the legacy of First Platoon may have been far different.

High-character organizations inculcate their values into the fabric of their culture. This does not happen by chance. Leaders at every level must internalize and live these values and, in doing so, set an example for others within the organization—whether it’s the Army, the local Parent Teacher Association, the Transit Authority, an investment firm, or other institution. This topic is so important that we devote an entire chapter to it later in this book and explore and describe specific examples from a variety of organizations of how to achieve a consistent positive occupational climate and culture. Positive character comes not just from within individuals, but from outside by living and working in settings where positive character is modeled and valued. Learning to form a positive culture in an organization is the most important thing that a leader may do to promote individual positive character among its employees, students, or members.

WHAT YOU DO AND WHO YOU ARE OUTSIDE THE LINES MATTERS

Following each Major League Baseball season, a single player from the hundreds of players among the thirty teams is selected for a great honor, the Roberto Clemente Award. This award is not given to the player who hits the most home runs or the pitcher who leads the league in strikeouts. Rather, it is given to the one player who “best represents the game of Baseball through extraordinary character, community involvement, philanthropy and positive contributions, both on and off the field.”11

Baseball fans will know that this award is given in Roberto Clemente’s honor not just because he was a Hall of Fame player, but because he placed the good of his community above his own safety and personal needs. Roberto Clemente was killed in an air crash just weeks after the 1972 baseball season while delivering supplies and aid to victims of an earthquake in Nicaragua.

In 2018, the Roberto Clemente Award was given to St. Louis Cardinals catcher Yadier Molina. A great player indeed, Molina may perhaps find himself in baseball’s Hall of Fame in Cooperstown following his playing days, but he is much more than just an amazingly talented catcher. Growing up in Puerto Rico in a baseball-obsessed family, young Molina heard his father tell stories about the great Roberto Clemente, and a picture of Clemente was proudly displayed in the family home.12 Molina’s father told tales of how great a player Clemente was, but praised him for being “even better outside the lines.” Yadier Molina must have taken his father’s words to heart. His good deeds and actions outside the lines consistently demonstrate character strengths from the moral virtue of humanity. Several years ago, Molina established a charitable organization, called Foundation 4, to assist youths impacted by adversity, including poverty, abuse, and cancer. Foundation 4 has built a safe house for children and purchases state-of-the-art equipment to help hospitals in Puerto Rico treat children with cancer and other severe ailments. Molina led efforts to provide aid to Puerto Rico as it recovered from Hurricane Maria. He raised more than $800,000 to support relief efforts and personally labored from dawn to dusk in Puerto Rico for fourteen consecutive days immediately after the storm, offering aid and comfort to victims.

To be a leader, whether of a baseball team, a military unit, or other organization, it is not enough to just do your job. Molina’s actions are those of a trusted leader. He is competent between the lines and outside the lines, and he applies the character strengths of kindness and capacity to love to every aspect of his life. In sports, as in other walks of life, we depend on our teammates to support and nurture us, and to help us fulfill our potential. Molina is this kind of person—through his own positive character, he raises up his teammates. Fans of all teams know well the deep impact that both good and bad role models have on team morale and performance.

THE CHARACTER EDGE AHEAD

In the chapters that follow, we dig deep into what aspects of character are most important in leadership. We explore individual and organizational attributes that are vital to effective leadership. We break these down into character strengths of the head, heart, and gut—that is to say, character strengths pertaining to good thinking, compassion for others, and courage. These are followed by a chapter focusing entirely on trust, expanding the ideas presented here, and a chapter devoted to the role of the organization in promoting, influencing, and sustaining positive character.

After expanding on the character attributes that make you a better leader, The Character Edge then examines how to select people for your organization that are not just competent, but also of high character. We then focus on how to cultivate individual positive character, looking at state-of-the-art approaches to this goal, including West Point’s Leader Development System. Instrumental to character development is learning from adversity and challenge, and we look at how this is accomplished, examine why people fail to display positive character, and discuss ways to mitigate against such failures. Even the best people sometimes fall short of their goal of honorable living, and we identify tactics that each of us may employ to guard against these failures.

We conclude with a chapter called “Winning the Right Way.” Here, we articulate the critical importance of character in all aspects of our lives and provide an integrated approach to achieving this goal. Throughout The Character Edge, we emphasize and illustrate the relationship between character and leadership. We look forward to leading you through this exploration. Character is significant to your well-being and to those whom you lead, follow, or teach. By learning to build and sustain character, you will be gaining the edge to success in life.