6

IT IS NOT JUST ABOUT YOU

Culture does not change because we desire to change it. Culture changes when the organization is transformed; the culture reflects the realities of people working together every day.

—FRANCES HESSELBEIN, FORMER CEO OF THE GIRL SCOUTS OF THE USA1

Your parents may have told you, when you were growing up, how important it was for you to associate with the right kind of friends. They meant that you are judged by the company you keep, good or bad. But there is more to it than that. Who you are is more influenced by your social environment than by any other factor. When it comes to character, this is especially true. Our focus thus far has been on individual character. Strengths of the gut, head, and heart determine who we are as a person and to no small degree how successful we are in school, work, and family and social relationships. Here we explore the powerful role organizations have on these strengths of character. High-character organizations promote and sustain positive individual character. How do they do this? What can leaders do to ensure their organization has a culture that achieves this goal?

JOHNSON & JOHNSON: A CASE STUDY

A crisis can come your way as a result of a leader’s misjudgment, misconduct, or negligence, or for reasons beyond his or her control. It can be expected, or it can come totally without warning. A true measure of character is not that the crisis appeared, but how the leader and the organization react to it.

An example of a company that suddenly found itself in the middle of a crisis is Johnson & Johnson, the world’s largest diversified health-products company. In 1982, seven people died from cyanide poisoning while taking one of Johnson & Johnson’s most popular over-the-counter drugs—Tylenol. Tylenol had 35 percent of the over-the-counter analgesic market in the United States and contributed 15 percent of Johnson & Johnson’s profits. Although the crisis was caused by only one person, who deliberately and criminally tampered with on-the-shelf bottles, consumers associated Johnson & Johnson with this incident. The company’s market value fell by more than $1 billion, and fear rose about the safety and reliability of every other Johnson & Johnson over-the-counter product.2 Suddenly and with no warning, Johnson & Johnson was in a crisis they did not cause, one they were totally unprepared to deal with, and one that could cause irreparable damage to the company.

We interviewed the current chairman of the board and CEO of Johnson & Johnson, Alex Gorsky. Mr. Gorsky, a West Point graduate who served in the US Army, entered Johnson & Johnson at the bottom ranks, working his way up. We asked him what drove Johnson & Johnson’s response to the Tylenol crisis, especially knowing the company was at risk of losing significant profit and inventory, and also of losing customer trust in their entire product line. Today, Johnson & Johnson touches more than one billion people every day with their products. That is a lot of customer value that was at huge risk when this crisis occurred.

Gorsky’s answer was immediate, unequivocal, and laced with honor and character: “Nothing is more important than not compromising your integrity to the people who trust and depend on you.” He said the leadership in 1982 never asked about the financial impact. They knew that overcoming the crisis meant taking responsibility for the incident and restoring the trust of their customers and their employees. The public expected this answer, but it does not come easily if you are focused on the financial results. A company of high values and integrity will place its organizational values above the bottom line and not think twice about the cost of what it will take to maintain trust with its customers and workforce. Where did these values come from for Johnson & Johnson?

The answer is their Credo. Johnson & Johnson’s Credo was created by Robert Wood Johnson II, who joined the family business at the age of seventeen and worked his way up to become the company president and eventually became chairman of the board in 1938. When World War II broke out, he was commissioned as a brigadier general in the US Army Reserves, helping to ensure the Army was supplied with necessary military goods and provisions. In 1943, Johnson reassumed the chairmanship of Johnson & Johnson and wrote the Credo, a set of business principles that captured the company’s commitment to integrity and character. The Credo was so important to Johnson that he had it carved into the wall of the company headquarters.

The Credo has stood the test of time with few modifications since its inception. Gorsky feels the Credo is not just a “moral compass” but also a “recipe for business success.” In our interview, Gorsky reflected on the current business environment, in which managers and executives frequently move from one company to another. At Johnson & Johnson, he said, all of the senior leaders have been with the company for twenty-five years or more, and many employees at all levels expect to spend their entire career with the company. This loyalty to the company is taken as proof that Johnson & Johnson is one of only a few corporations that have flourished through a century of change and innovation. Gorsky declared, “Johnson and Johnson is a career, not just a job. It [the company] becomes like family.”3

THE JOHNSON & JOHNSON CREDO

We believe our first responsibility is to the patients, doctors and nurses, to mothers and fathers and all others who use our products and services. In meeting their needs everything we do must be of high quality. We must constantly strive to provide value, reduce our costs and maintain reasonable prices. Customers’ orders must be serviced promptly and accurately. Our business partners must have an opportunity to make a fair profit.

We are responsible to our employees who work with us throughout the world. We must provide an inclusive work environment where each person must be considered as an individual. We must respect their diversity and dignity and recognize their merit. They must have a sense of security, fulfillment and purpose in their jobs. Compensation must be fair and adequate and working conditions clean, orderly and safe. We must support the health and well-being of our employees and help them fulfill their family and other personal responsibilities. Employees must feel free to make suggestions and complaints. There must be equal opportunity for employment, development and advancement for those qualified. We must provide highly capable leaders and their actions must be just and ethical.

We are responsible to the communities in which we live and work and to the world community as well. We must help people be healthier by supporting better access and care in more places around the world. We must be good citizens—support good works and charities, better health and education, and bear our fair share of taxes. We must maintain in good order the property we are privileged to use, protecting the environment and natural resources.

Our final responsibility is to our stockholders. Business must make a sound profit. We must experiment with new ideas. Research must be carried on, innovative programs developed, investments made for the future and mistakes paid for. New equipment must be purchased, new facilities provided and new products launched. Reserves must be created to provide for adverse times. When we operate according to these principles, the stockholders should realize a fair return.4

When you read this, Johnson & Johnson’s values and principles are immediately apparent. Gorsky told us he goes back to the Credo quite often; it is important not only to him as the CEO, but also to the entire corporation because “it defines our purpose.” He feels the organization must lead the effort to develop personal traits defined by the values articulated within the Credo. He believes “the most important characteristic in Johnson and Johnson is espousing the values in the Credo.”

To drive this ethic throughout the entire organization and through all levels of management, Gorsky looks for opportunities to talk about the Credo, to demonstrate its principles, and to ensure that his management team is doing the same. “Senior leaders are the role models, and they must live the Credo every day.” According to Gorsky, the Credo is talked about at the beginning and end of every meeting.

During their performance assessments, employees are asked to sit down with their manager and read the Credo line by line and explain what it means to them. Then the employee signs it and is asked to display it in a prominent place at his or her workplace. The employee’s Credo assessment becomes one of the key factors management considers for developing their future leaders. “Character and values are part and parcel to our [leadership] development process. It is everything we do.”

Strengths of the head—curiosity, love of learning, creativity, open-mindedness, and perspective—are especially important to a company such as Johnson & Johnson. Innovation is essential to success. “With new ideas, we are pleased but never satisfied,” Gorsky commented. “Diplomas have a short half-life—your diploma is nothing more than a license to learn.” Emerging developments in cell-based therapies, genomics, and robotic surgery are topics the company must be smart about. “It is not just about biology and chemistry anymore. Just as new cars have advanced technologies, such technologies will be deployed in surgery within the next ten years.”

Does it make a difference when the leader of a corporation drives values-based character throughout the entire organization? In the 1982 Tylenol crisis, it certainly did. The company won praise for its quick and immediate actions, and within five months the company recovered 70 percent of its market share of this drug with continued improvement over the following years. They put solid measures in place to ensure no recurrence. Through their competence, character, and caring, they reestablished trust with their customers. Evidence even suggested that some consumers switched from other brands to Tylenol because of Johnson & Johnson’s transparent, authentic, and values-based response to this crisis.5

A GUIDE TO DEVELOPING HIGH-CHARACTER ORGANIZATIONS

Excellence does not happen by chance, and building and sustaining a high-character organization is no exception. It takes deliberate and systematic efforts and requires leaders to embrace the importance of character within an organization. Johnson & Johnson’s Credo and their focus on it at every level throughout the organization shows how, even in a large corporation, such a positive culture can be instilled. The result of the Credo is “360-degree trust”—confidence that all in the organization will do their best to do the right thing and in the right way to achieve the company’s goals.

Values-based trust is the foundation upon which high-character organizations rest. We have explored the three C’s of trust—competence, character, and caring. These are prerequisite traits and skills individuals must possess to be trusted by their peers, subordinates, and leaders. But what can an organization do to inculcate and encourage its members to excel in the three C’s?

Patrick Sweeney, retired from the Army and now the director of Wake Forest University’s Allegacy Center for Leadership & Character, created a conceptual model that captures how high-performing organizations maintain excellence in the face of personnel turbulence and character failures. The Individual-Relationship-Organization-Context (IROC) model describes the complex relationships among organizations, individuals, and the context in which they operate, and how these relationships influence trust and sustained high performance. The following chart summarizes the IROC model.

INDIVIDUAL CREDIBILITY

- Competence

- Character

- Caring

RELATIONSHIPS MATTER

- Respect and concern

- Open communications

- Cooperative interdependence

- Trust and empower others

ORGANIZATION SETS THE CLIMATE

- Shared values, beliefs, norms, and goals (culture)

- Structure, practices, policies, and procedures

CONTEXT INFLUENCES ALL

- Dependencies and needs

- Organization systems

INDIVIDUAL CREDIBILITY

Almost all organizations understand and value the importance of competence among individual employees. Universities evaluate the potential of prospective students using a variety of competence indicators, including standardized test scores such as the SAT or ACT and high school grades.6 The armed forces use the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) to screen and classify hundreds of thousands of recruits every year. The development of the first large-scale aptitude tests resulted from the need during World War I for the services to screen their recruits, allowing them to assign new members to jobs for which they possessed the aptitude and competence to succeed.7

Organizations differ on what defines competence. Most jobs require intelligence, but some may have additional requirements. Law enforcement agencies, for example, typically require applicants to pass both a medical examination and tests of physical strength and agility.

Smaller organizations may not be able to afford formal testing. So they often employ proxies for competence. Completion of a college degree is commonly held to be a reliable indicator of mental ability. Except for specialized jobs such as accounting or finance, employers typically do not select an applicant based on the subject of his or her college degree. Completing a two- or four-year degree in any subject is generally proof of sufficient intelligence to do the job.

Other organizations may focus primarily on physical skills. Professional sports teams carefully evaluate future players on this domain. To be a great player, the other two C’s are critical, but physical competence comes first. Basketball teams systematically evaluate past performance in high school or college and also look at a variety of specific skills and attributes. Speed, leaping ability, arm reach (many top professional basketball players have a “wingspan” longer than typical of others their same height), hand size, and aerobic capacity are evaluated. Baseball scouts seek the “five-tool player,” who possesses speed, can hit for power, hit for average, field well, and has a strong throwing arm. With the advent of advanced metrics, these five tools are supplemented by measurements such as exit velocity and launch angle for batted balls.

Once an employee is selected into an organization, efforts follow to take the basic aptitude and skills to a higher level. Universities hone the intellectual skills of students with four or more years of academic courses. Law enforcement agencies spend months training specific skills needed to be an effective officer. Once drafted by a major league team, most baseball players spend several years in the minor leagues further sharpening the skills needed to excel in “the show” (baseball slang for the major leagues). The military probably takes the prize in skill development. An officer who retires at the rank of colonel will likely have attended four or more specialized courses in his or her career, some of which last a full year.

The bottom line is this: organizations must carefully define the set of skills they need within their organization, select people into the organization who possesses these skills, assign them to jobs that match their talents, then continue to train and develop each employee throughout his or her tenure within the organization.

This leads to competence. But it is not enough.

Character is the second component of individual credibility. While many organizations understand and value the importance of character, they are less sure of how either to select high-character individuals or to further develop character once the individuals join the organization. Unlike for competence, no widely accepted standardized tests for character exist. The Values-in-Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS) is useful for personal feedback and reflection but was not designed for screening and selection. Potential employees could easily “game” the VIA-IS by providing what they think are the right answers. The same holds true for other questionnaire-based character assessments.

Consequently, organizations turn to indirect indicators of character. West Point selects high school students who were team captains or class presidents. Baseball teams look at a player’s “makeup,” by which they mean past actions and behavior consistent with team values. Law enforcement agencies do extensive background checks on potential officers, interview them, talk with neighbors and others that know the applicant well, and conduct a criminal-history check to screen out applicants with a prior history of violating the law.

The following case study underscores the importance of character among a group of the most competent basketball players in the world.

In the early summer of 2008, the leadership of the Twenty-Fifth Infantry Division participated in a program designed to prepare them to build an effective team for their upcoming Iraq deployment. Their deployment would occur toward the end of the now-infamous surge, and the division would have responsibility for some of the most contentious areas in all of Iraq—the northern Sunni provinces and the three Kurdish provinces. The mission included interdicting foreign fighter flow across the Syrian border, interrupting Iranian weapons and fighters across the Iranian border along Diyala province, countering the remnant Baathist nationalism in Saddam Hussein’s home province of Salah ad Din, integrating the former radical Sunni insurgents (now called the Sons of Iraq) into the Iraqi Army, defeating the remaining radical Sunni insurgents (who later evolved into the Islamic State fighters, or ISIS), and building a relationship between the Kurdish and the Iraqi central governments. It was a complex security environment to be sure.

In addition, the Twenty-Fifth Division would not deploy with all of its own subordinate commands. It was being assigned units from other US Army divisions, thus making the challenge of building a team even more problematic.

The assistant division commander, Brigadier General Bob Brown, a former West Point basketball player and team captain, was fortunate to have a strong relationship with Duke basketball coach Mike Krzyzewski, who had been Brown’s coach at West Point. To assist the Twenty-Fifth Infantry Division in team building, Brown reached out to Krzyzewski (commonly known as Coach K), asking him to talk with division leaders before the deployment. Coach K was busy preparing the USA Men’s Olympic basketball team for the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing, China. But he made time to spend an evening with the division. In that single evening, he taught the leaders of the division a lesson on leadership; one that he later used to completely turn around the fortunes of the USA basketball team (they won the 2008 gold medal after an embarrassing showing in the 2004 Olympics); one that taught the division leaders lifelong lessons on team building and leadership that played out significantly during combat operations in northern Iraq once the division deployed.

Coach K’s turnaround of the fortunes of the USA basketball team is nothing short of amazing. Contrary to the winning traditions of USA basketball over many years, and contrary to its tremendous talent compared to that of all the other teams, the 2004 team lost three games and ended up settling for an embarrassing bronze medal. An average person would think that an Olympic bronze medal is a great achievement, but looking at the talent, the circumstances, and the tradition of excellence over many years, fans in the United States and across the globe knew that the 2004 team had the potential to repeat a USA gold medal performance but failed to do so. Numerous articles and opinions have been written about why the team did not win, but clearly this group of All-Stars failed to become a cohesive unit; individual players were more concerned with their own performance than with what was good for the team, and the coaching style failed to optimize the talent on the court. The result: a lackluster performance and great disappointment for both the players and the American sports world.

To change this culture and prepare for the 2008 Olympics, the USA basketball director brought in Krzyzewski, who emphasized team unity. Coach K recognized the huge athleticism advantages of the NBA players and learned how to exploit these gifts without too much focus on a stricter set of offensive sets and defensive rules. His players were not only playing for the team, but were also allowed to showcase their athletic prowess.8

What was not discussed in any analysis or articles written about the transformation Coach K achieved is what he shared with the Twenty-Fifth Division leadership at their team-building session. He revealed the principal criteria he used to determine who would be a member of the USA basketball team.

Keeping in mind the lessons of the past teams, Coach K decided that character was the most important criterion for his 2008 team selection. To personally assess the character of each team member, he talked with each player in the player’s living room or kitchen with the player’s family present. While discussing the prospect of playing on Team USA, he also watched how the players interacted with their family. Coach K felt that how the players treated their own family was a crucial indicator to how they would treat the other members of the Olympic team, and how they would balance the importance of the team with their individual ego. The most important criterion to a team’s winning performance was the team’s character. Would they be out there playing only for themselves? Or would they play for the good of the team? What was most important? Me? Or team?

This incredible lesson is applicable not only to athletic sports teams at the highest level, but in all other aspects of leadership as well. The Twenty-Fifth Division hung on to that lesson throughout their entire deployment. All of America was proud to see how well that culture took hold within the 2008 USA Olympic men’s basketball team, as they were undefeated in the tournament, leading once again to a gold medal.

Krzyzewski was also asked to coach the USA basketball team from 2013 to 2016. Coach K asked Caslen if he could bring the team to West Point, engage with cadets both informally and in scrimmage basketball, and schedule a guided tour of the West Point cemetery. The West Point cemetery is hallowed ground—the final resting place of West Point graduates who have served their country and given their lives. It includes notables like General Norman Schwarzkopf, commander of coalition forces in the 1991 Gulf War; Lieutenant Laura Walker, the first female West Point graduate to die in combat, during Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan in 2005; Lieutenant Emily Perez, the first female graduate of West Point to die during Operation Iraqi Freedom, in 2006; General William Westmoreland, who served as US Army Chief of Staff, superintendent of the US Military Academy, and commanded US forces in Vietnam from 1964 to 1968; and Lieutenant Colonel Ed White, the first American to walk in space, who was killed in the Apollo 1 fire on January 27, 1967.

Caslen asked Coach K why he wanted the basketball players to visit the cemetery. His reply was that these well-known NBA players would be playing for their country, and he wanted them to know the meaning of sacrifice and duty to country. At the West Point cemetery, they would visit the graves of men and women of all ranks who gave their lives in defense of our country’s values. He wanted the players to reflect on that sacrifice and to know that playing for your country is nothing compared to giving your life for your country.

The attribute of caring is like character in that no simple tests exist to identify individuals with a genuine concern for others. Organizations can use strategies to identify potential employees who care about others, such as looking in interviews and background checks for evidence of behaviors that signal caring. Look for a pattern of volunteering to help others, for example. Interviews with previous employers and coworkers may be revealing.

Once an individual is accepted into the organization, this third C can be nurtured and developed, similar to character and competence. Community service is an expectation for West Point faculty (and for members of many other organizations). Most professional sports teams embrace community service and assist players and other personnel in doing good works in their communities. Doing so reinforces the attribute of caring and ingrains it into the organization’s culture.

Leaders should engage in deliberate strategies to demonstrate caring. For decades, the San Antonio Spurs have been a winning organization. In no small measure, this is because they embrace the three C’s model. They recruit and develop top-notch talent, make character a core focus for all team members, and through their leadership demonstrate and build caring among the players, coaches, and staff.

R. C. Buford, the long time Spurs general manager, now CEO for Spurs Sports & Entertainment, told Dr. Matthews a story that demonstrates how the Spurs create a caring culture. One of their players, Patty Mills, is an Australian with Aboriginal roots. Growing up, he heard many racist taunts, similar to what African Americans experience in the United States. One of Mills’s heroes is Eddie Mabo, who is often described as the Martin Luther King, Jr., of Australia. Australia celebrates Mabo Day on June 3. Little known outside Australia, this observance is of major significance especially to Australians with Aboriginal heritage.9

On June 3, 2014, the Spurs were preparing for an important playoff game. Legendary coach Gregg Popovich (“Pop” to his players and fans) gathered the players during the last practice before this critical game. Most coaches might have reviewed game strategy or offered a “win one for the Gipper” pep talk. But Popovich chose a different approach. He asked Mills to tell the rest of the team who Eddie Mabo was and why he was so important to Mills. The players listened with rapt attention, setting aside their thoughts about the upcoming game to hear Mills tell Mabo’s story. Hearing this story on Mabo Day was riveting.

What did Mills and the other Spurs players learn from this? More than anything else, they learned that Coach Popovich genuinely cares about his players. By asking Mills to share the story of Eddie Mabo, Pop put the game of basketball into proper perspective. The other players, many who had experienced racism themselves, forged an even stronger emotional bond with their Australian teammate. In this simple act, Popovich demonstrated decisively the caring that the Spurs organization has for its players.

Leaders in all types of organizations and at all levels can learn from this example. There is no simple method for establishing a climate of caring. Leaders must first realize how important caring is to organizational excellence and, second, think of ways to demonstrate caring. Like Popovich, take time to know each employee. Learn about what matters to him or her. Send a thank-you note when he or she does something well. Spend a little one-on-one time each day with your immediate subordinates and set the expectation that they will, in turn, do the same with their own subordinates. The key is to be consistent and genuine. Caring cannot be faked. Employees sense fakery immediately. Thus, a major responsibility for senior leaders is not just to be caring themselves, but to make caring a key attribute for those they promote to management and leadership positions.

RELATIONSHIPS MATTER

The late psychologist and pioneer of positive psychology Christopher Peterson summed up his life philosophy in three simple words: “Other people matter.”10 This is the crux of high character and of high-performing organizations as well. When leaders show respect and concern for their employees, communicate with them frequently and openly, and trust and empower workers at all levels, good things follow. These factors enable what Sweeney calls cooperative interdependence. It is more than a case of “I will scratch your back if you scratch mine.” Instead, cooperative interdependence refers to an organizational culture in which leaders and followers share a common vision and goals and recognize that success hinges on working together to achieve that mission and those goals.

Observe any high-performing organization and you will see these relationship principles playing out. We have already discussed the San Antonio Spurs, which is hands down the most successful National Basketball Association franchise for the past quarter of a century. The Spurs have built their success in no small measure around valuing positive relationships. Positive relationships build and sustain good character. And good character, coupled with competence and caring, allows the team to win year in and year out.

Dr. Matthews observed the Spurs practice the day before the first NBA playoff game in April 2017. R. C. Buford sat with him on courtside folding chairs and talked with some awe about how Coach Popovich nurtures positive relationships with and among players. Buford instructed Matthews to watch closely how Pop interacted with each of his players during the practice session. He said that Pop would, during the practice, approach every player on the team and literally place his hands on him, look him in the eye, and engage personally. Pop did just that. It didn’t matter if you were the top star on the team or the last player on the bench, Pop engaged with everyone.

This touching and engaging with players is just one ingredient in a veritable cocktail of positivity that Pop immerses his team in, day in and day out. His team dinners are legendary. A wine connoisseur and gourmet foodie, Coach Popovich frequently treats his team to dinner, especially while on the road. He sees meals as an opportunity to build relationships. He doesn’t do this in a haphazard way. Players come into the league with vastly different experiences and backgrounds, and team dinners help the team form and reinforce its own positive culture. Coach Popovich thinks of every detail. Buford says that Pop enlists the aid of experienced and more socially adept players to sit with and encourage new players to feel part of the team. These dinners address all components of Sweeney’s relationships factor. They set the occasion for open communication and show respect and concern; they also empower players, build trust, and establish conditions for cooperative interdependence.11

How does your organization rate on this relationship factor? Make a list of things your leaders have done to build relationships. Chart a plan for what you can do at your level in the organization, whether you are the CEO, a midlevel manager, or a team leader. When leaders and managers make relationships a priority, workers follow suit.

ORGANIZATIONS SET THE CLIMATE

Leaders make their greatest impact by establishing an organizational climate that embraces character and positive relationships. Johnson & Johnson’s Credo is a stellar example of how a large company makes its values, beliefs, norms, and goals public. High-character organizations support these values, beliefs, norms, and goals with structures, practices, policies, and procedures that ensure that they are met.

CONTEXT INFLUENCES ALL

Organizations differ in mission and structure. The organizational chart of a university is not the same as that of an infantry combat brigade. Even within a given organization, the context changes. The infantry brigade deployed in combat faces different contingencies than when in garrison. Specific goals and strategies must adjust to account for these contextual changes. But an organization’s core values remain the same. Johnson & Johnson did not change their Credo in response to the Tylenol crisis, nor was it changed in response to fluctuations in the economy. The focus of the San Antonio Spurs on IROC principles remains constant in the face of changing players and team success.

When we say that context influences all, we mean that specific tactics, techniques, and procedures must change as we adapt to different conditions. For example, Sweeney tells us that in a dangerous context, such as combat, followers naturally depend more on leaders to provide for their physical safety and emotional well-being. His study of soldiers showed that in combat they placed their highest reliance on their leader’s “competence, loyalty, integrity, and leadership by example.” From the leader’s perspective, the importance of empowering and trusting subordinate soldiers to accomplish the mission was highlighted. In these conditions, successful leaders “place great importance on follower characteristics of competence, honesty, and initiative, which help ensure mission completion.”12

CASE STUDIES OF ORGANIZATIONAL EXCELLENCE AND FAILURE

SAINT THOMAS HOSPITAL

A good example of the pivotal role that leaders play in setting a positive organizational climate comes from Dr. Deborah German at Saint Thomas Hospital. German is a second-generation Italian American who grew up aspiring to be a medical doctor. Because of her talent and potential, not only did she graduate from Harvard Medical School and become a fellow in rheumatic and genetic diseases at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, but she was also a brilliant hospital administrator and is currently serving as the founding dean of the University of Central Florida College of Medicine and vice president for health affairs. How did she catapult from being a medical doctor to a proven leader of large organizations? Simply because she is a compassionate and caring leader with incredible competence and character. And one with an amazing talent to create a character-laden organization.

In 1988, Dr. German joined Vanderbilt University in Nashville as associate dean for students and later senior associate dean of medical education. After thirteen years at Vanderbilt, Dr. German was selected to serve as president and CEO at Saint Thomas Hospital in Nashville. This hospital is part of a system that overspent its budget. At the time, the hospital budget needed to gain an additional $2 million a month but was losing $2 million instead. The crisis was so bad that the system CEO’s guidance to Dr. German was to immediately cut the workforce by 10 percent—or said another way, to fire 350 employees. How would you like to face a situation where you are told to fire 10 percent of the workforce? Who would want to work in an environment such as that?13

Dr. German knew the catastrophic outcome these actions would have on the morale of the remaining employees. She knew this because she was a hands-on CEO, and because she cared for each of them. She worked closely with the employees and knew the pressure and burdens they were already under. If anything, she felt she needed to increase the workforce by 10 percent, not fire 10 percent.

To deal with this dilemma, she brought the leadership together. She recognized that institutional expertise resided with the department heads. They were the hospital’s experts, dealing with the organization’s problems every day. She believed that if she could collectively unleash this body of intelligence, together they would fix this problem.

By bringing everyone together, she shared their thoughts on the problem and solicited feedback on how to address it. She brought in both administrators and doctors. At the first meeting, to demonstrate her trust in her leadership to solve this problem, she stated that the first person to be fired would be her own daughter (who worked in the hospital), then herself. After explaining the problem, she asked each of her leaders to present this briefing to their subordinates with the goal that every person in the hospital would not only share knowledge of the issue and concern, but each person would also have the opportunity to offer ideas on a solution.

For the next two weeks, the leadership team met every day from 6:00 A.M. to 8:00 A.M., to discuss the incoming ideas. The intent was to encourage everyone to get involved, and to think of ways to solve this problem, both innovative and traditional. During the meetings, the entire team would drill down on every proposed solution and see how it could be implemented.

Dr. German told her leadership that if you take one stick and bend it, it will easily break. But if you take a couple dozen sticks together and try to break them, it is nearly impossible. By ourselves, we will lose. But with all of us together, we will win. And win they did.

A great idea came from one of the assistants whose job was to push newly discharged patients in their wheelchairs out the front door to their waiting ride home. The hospital would put a pillow or two in the wheelchair for comfort, and naturally the patient would want the pillows in the car to provide comfort on the ride home. The hospital had been doing this for years, and when the administration examined its cost, they found it was nearly $1 million a year. The assistant suggested encouraging new in-patients and their families to bring to the hospital the patient’s pillow from home. It would not only provide the comfort and security of using one’s own pillow but also would comfort the patient on discharge and the ride home. This grassroots solution not only saved the hospital nearly a million dollars a year, but also provided more comfort and appeal to patients. It was a win-win!

Dr. German was brilliant in approaching her hospital’s financial problems, but her compassion, empathy, and caring for every person in her workforce steered her toward solutions. By involving every employee, she unleashed the potential of every doctor, administrator, and staff member. Dr. German demonstrated personal responsibility and a sense of urgency and priority.

Because of this initiative, within three to four months the hospital eliminated the $2 million monthly deficit and was saving more than $4 million a month without firing a single person. That was the tangible outcome, but intangible outcomes included long-term benefits such as an increase in morale, greater trust and cohesion within the team, and, probably most important, the trust and confidence the entire organization had in their president and CEO, Dr. Deb German.

Is caring an important criterion in a leader with strong character? You bet it is! Just spend an hour or so with Dr. German, and you will want to be on her team every day.

FRANCE TÉLÉCOM

We have seen how high-performing organizations strive for competence, character, and caring to optimize their organizational climate and promote excellence among their employees. We have also looked at examples of organizations that are lacking in one or more of the elements of competence, character, and caring and the adverse impact this has on the organization and its individual members. Implicit in our discussion is the assumption that such organizations are motivated to address these deficiencies to regain the trust of their employees and improve productivity and morale.

What happens when an organization intentionally violates the principles of competence, character, and caring so as to undermine the trust and confidence of its employees? France Télécom (formerly the national phone company, now a private company called Orange) provides such an example. In an article published in The New York Times, writer Adam Nossiter describes what happened when France Télécom engaged in “moral harassment” of its employees in an effort to drive them to quit the company. According to Nossiter, company executives believed they needed to reduce their workforce by 22,000 out of 130,000 to make the company more competitive. Because of French laws protecting the rights of workers, the company could not easily fire them, so the executives allegedly decided to create such poor work conditions that employees would voluntarily resign. But given the poor job market in France, most workers clung to their jobs and attempted to endure whatever tactics management inflicted upon them.14

Management had set about their task using a variety of means. Some workers were reportedly reassigned to jobs that they were ill prepared for or did not like. Some were given meaningless tasks or no tasks at all. In doing so, management made clear to the employees that money mattered more than the welfare of the workers. Management created a work environment that clearly communicated to the employees that the company did not care about them.

In his New York Times article, Nossiter describes the most horrendous impact of this strategy on workers. In a lawsuit filed on behalf of the workers, former executives of France Télécom were sued for moral harassment. Prosecutors claimed that at least eighteen suicides and thirteen attempted suicides occurred among France Télécom workers between April 2008 and June 2010. In December of 2019 Reuters reported that a Paris court found the telecom group (now known as Orange) and the former CEO guilty of moral harassment. Although Orange continued to deny that “there was any systemic plan or intention to harass employees,” the telecom group said it would not appeal the verdict.15

The outcome of these policies by France Télécom are entirely predictable based on psychologist Martin Seligman’s learned-helplessness theory. Seligman discovered that when animals and humans are presented with inescapable harm, many develop symptoms of depression. If, in this case, workers had other employment alternatives, they would likely have quit their jobs as management desired and pursued other options. But the poor job market forced most to remain at their jobs, and feelings of helplessness and depression built over time. Just like the dogs in Seligman’s original studies of learned helplessness, thousands of workers suffered significant emotional stress.16

We hope this represents a rare example of organizational abuse of employees. Whether intentional or not, the France Télécom case unequivocally demonstrates the profoundly adverse impact that an organization’s violations of character and caring have on its employees.

ASSESSING YOUR ORGANIZATION

We recommend evaluating your organization’s performance on the IROC principles. Give this questionnaire (Worksheet 6.1) to all or a sample of your employees. Carefully examine their responses. High responses (4s and 5s) indicate your organization is doing well on these factors. Lower responses (1s, 2s, and 3s) may indicate areas of concern. Feedback from this evaluation may be used to develop strategies for improving your organization’s climate.

WORKSHEET 6.1: IROC ORGANIZATIONAL RATING FORM

Use the following 5-point scale to rate your organization for each question below:

1 = VERY POOR

2 = POOR

3 = AVERAGE

4 = ABOVE AVERAGE

5 = EXCELLENT

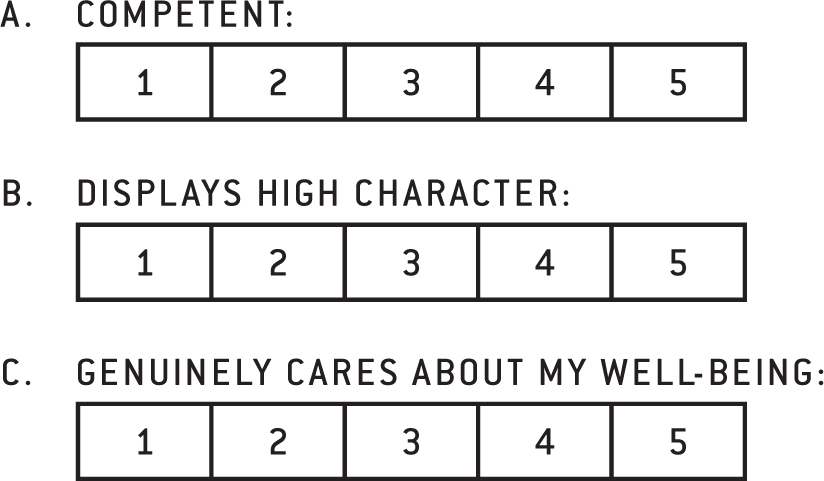

Individual credibility. In my organization my senior leader is

Relationships. In my organization my senior leader displays ________________________ toward others.

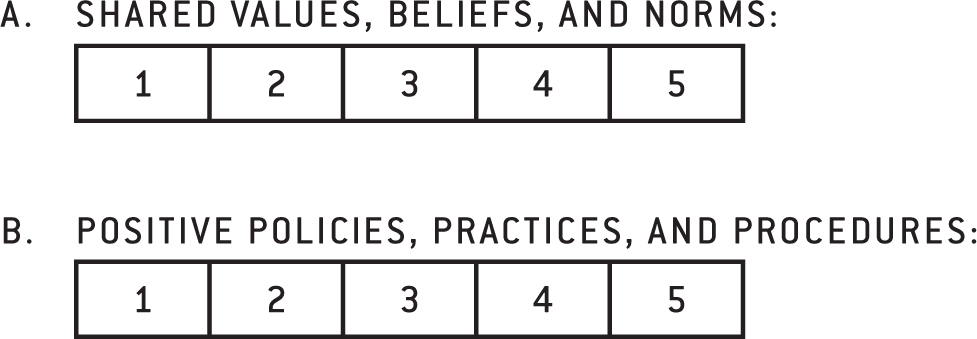

My organization includes

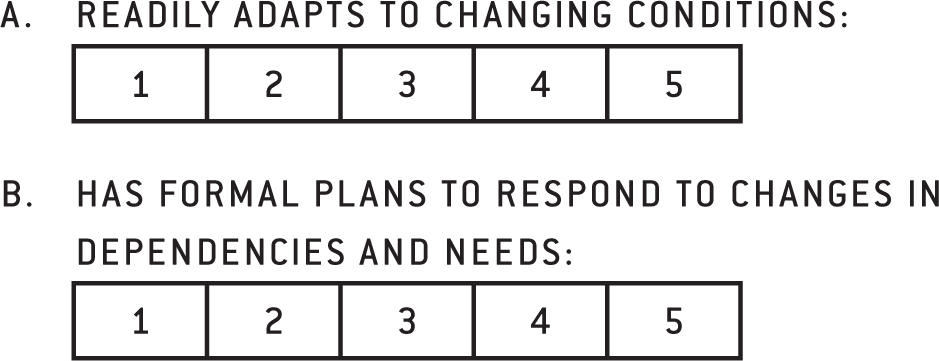

My organization

SUMMING UP

Character does not occur in a vacuum. Establishing a strong and positive organizational climate and culture that follows the IROC principles is necessary for lasting success. Organizations such as Johnson & Johnson and the San Antonio Spurs that do this win consistently. Organizations that fail to live up to the IROC principles suffer greatly. Begin with an IROC assessment, using our simple survey or by devising your own assessment. Use the results to develop a plan, if necessary, to improve your organizational climate. Winning, winning consistently, and winning the right way hinge on building a positive organizational climate.