8

NURTURING THE SEED OF GOOD CHARACTER

Good character is not formed in a week or a month. It is created little by little, day by day. Protracted and patient effort is needed to develop good character.

—HERACLEITUS1

Farmers understand the need to purchase the best seeds to produce the best crop. Seeds contain the genetic code for their growth. Selecting good-quality seed not only increases yield, but it also produces plants that are resistant to various diseases and disorders. But farmers also know that high-quality seed, while necessary, is not sufficient to ensure a bumper crop. The quality of the soil is also important. So, too, is the care and nurturing the farmer provides as the crops mature. Farming would be a lot easier if all that was necessary was to plant the seed and wait until the beans, tomatoes, corn, or other produce was ready to harvest. Spring and summer could be spent fishing or traveling instead of tending to the fields!

Character is akin to seeds in this respect. Selecting people of high character to be part of your organization is necessary to establish a high-character organization. This is analogous to the farmer’s care and consideration in seed selection. Creating and maintaining an environment that reinforces good character is also critical. We saw how high-performing organizations such as the Spurs do this year in and year out. This is similar to the farmer planting the seed in soil that is favorable to seed growth. But just as crops need tending, so character needs to be developed. You can begin with the best seeds but still fail to produce a quality crop. And you can begin with high-character individuals in your school or workplace and still end up with a character-challenged organization.

Character must continually be developed. It is not something you have or don’t have. Even people considered to be icons of character sometimes fail to behave morally or ethically. There are many examples. You may think of character failures in your own life or ones you have observed in others.

Retired general and former director of the Central Intelligence Agency David Petraeus is a case in point. A native of Cornwall-on-Hudson, New York, and the son of the commander of a World War II Liberty ship, it was almost inevitable that Petraeus would attend West Point, just a few miles down the Hudson River from his home. He excelled at West Point, graduating in the top 5 percent of his class. He had an outstanding career in the Army, commanding at every echelon. His strategy as a division commander in the Iraq War is regarded as one of the most highly effective strategies employed by US troops. He went on to several higher commands, including of the Army’s Combined Arms Center, the United States Central Command, and the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan.

Petraeus retired from the Army in August of 2011 at the rank of four-star general. Shortly thereafter, he was sworn in as the director of the Central Intelligence Agency. Here his problems began. He was discovered to have engaged in an extramarital affair with Paula Broadwell, herself a West Point graduate, and to have shared classified information with her. Petraeus was ultimately charged with and pleaded guilty to unauthorized removal and retention of classified material. Petraeus resigned as CIA director on November 9, 2012, after serving for just fourteen months in that position.

West Point carefully selected Petraeus into its class of 1974 and provided him with an optimal environment (soil) for continued growth. For the vast majority of his Army career, he served in exemplary fashion. Petraeus’s behavior when he shared classified information was clearly “out of character” for him given his decades of honorable service. While we will never know what led Petraeus to these acts, one way to inoculate ourselves and others against similar failures is to pay attention to the third piece of producing a good crop—nurturing and cultivation of character.

THE BIG THREE

Cultivating good character may at first seem like a daunting task. But high-functioning organizations use a variety of strategies to do this. When you think of high-character organizations, what comes to mind? Scouting, religious institutions, schools from K–12, and colleges and universities. What is the common denominator across these diverse institutions?

Psychologists have identified what are called the big three factors in shaping character: (1) positive and sustained mentoring, (2) skill-building curricula and training, and (3) leadership opportunities.2 Some institutions systemically integrate all three of these factors into their development efforts, while others do so intuitively, and some fail to do it at all.

POSITIVE AND SUSTAINED MENTORING

Positive and sustained mentoring is fundamental to cultivating character. You will see this in all high-performing organizations. The San Antonio Spurs director of basketball operations and innovation, Phil Cullen, provided us with a great example of the power of mentoring. Basketball fans are quite familiar with the legendary player Tim Duncan. For those not familiar with him, Duncan was the Spurs’ leader both on and off the court in a career that spanned nineteen seasons, beginning in 1997. Along the way, he led the Spurs to five NBA championships, was on the NBA All-Star team fifteen times, and was the most valuable player (MVP) in the 2000 All-Star game. He represented the United States in the 1994 Olympic Games, while still playing college basketball at Wake Forest University, where he earned his bachelor’s degree in psychology. He was twice selected as the NBA’s MVP. He has many other achievements, but you get the idea.

A player of this caliber could be excused for developing an inflated ego. Fans of the NBA and other sports see this frequently. An elite player demands special treatment, is easily offended by the press, and is more concerned with individual statistics and accomplishments than the team’s win/loss record. Duncan, however, consistently displayed the positive character traits of humility and teamwork throughout his great career.

Cullen told Matthews about an incident during summer practice in 2018. Summer practice gives the team’s management and coaching staff a chance to observe the skills and “makeup” of players, especially newly selected draft picks or players newly acquired via trade or free agency. The word makeup is used in sports to describe the psychological, social, and emotional traits of a player. From our perspective, makeup is a shorthand way of saying the player has the positive character traits—grit, teamwork, courage—to excel in the game.

In this particular practice, a rookie draft pick was doing his best to impress the team. He gave 100 percent effort to every drill. Nearly exhausted following a particularly tough session, this player vomited on the court. This is not especially unusual in sports, but what happened next is. None other than Tim Duncan appeared, towel in hand, and cleaned up the vomit. He then encouraged the young (and perhaps embarrassed) player to keep up the hard work. In mentoring, what message did this simple act communicate not just to the rookie but to all the other players who witnessed it? If we break it down by head, heart, and guts, Duncan mentored this player and his teammates on the character traits of perspective, bravery, kindness, leadership, and humility, just to name a few.

Many other Tim Duncan stories also illustrate the power of mentoring. He was always the first to arrive at practice and the last to leave. Even now, although retired from playing in 2016, he follows the same pattern. This sets a great example for other players, who look up to him as the legend he is. Although he was not formally on the coaching staff until 2019, Duncan has always worked with players during practices to build skills, frequently spending much of his time with the second- and third-string players.

Who are the mentors in your organization? They may or may not be managers or officially designated leaders. Positive mentoring occurs just as often, perhaps more so, among coworkers. Whom do you look up to, and why? What can you do to be more like them?

We caution that mentoring can have a dark side as well. In a dysfunctional organization, negative mentors may emerge. The boss who holds employees accountable to a strict schedule but takes two-hour lunches would be an example. The athlete (in any sport) who seeks special treatment and cares only about his or her own performance is another. Whether you are a student, an athlete, or an employee in a large corporation, people like this are always around. If they are charismatic, they can have a profoundly negative impact on you and the organization. Organizational leaders are advised to be on the lookout for such people, and to remove them from the organization if they do not respond to counseling. Phil Cullen explained that being on the lookout for positive character—and evidence of poor character—is an important consideration in deciding which players to draft, sign as free agents, trade for, or release or trade away. High character players are sought out, and those with questionable character are best either not recruited and signed, or removed from the team. Sometimes addition by subtraction works.

On being an effective mentor. Effective mentoring does not happen by chance. While peer mentors emerge within organizations and may be helpful in crafting and maintaining a positive culture, leaders and managers need to have a systematic plan to ensure that mentoring occurs, and that it is framed around the organization’s goals and values. We offer the following suggestions:

1. Leaders and managers must make mentoring a priority and follow through with it in a timely manner. While day-to-day, informal interactions between leaders and subordinates are important, time should be set aside in formal meetings for in-depth discussions.

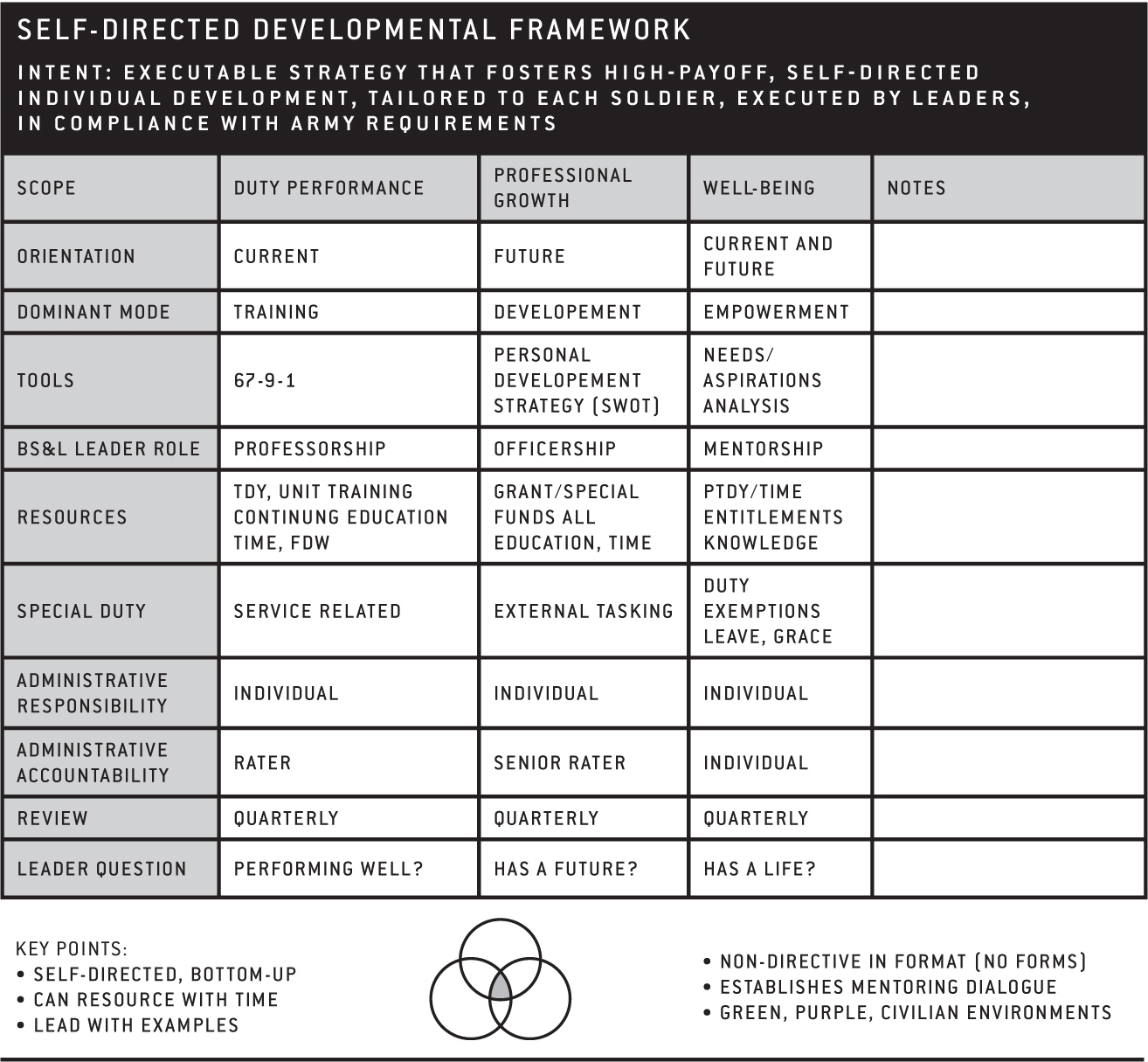

2. Formal mentoring sessions should be structured. It helps to ask employees to complete a self-development assessment plan prior to the meeting and to use that plan as the basis for discussion. The Behavioral Sciences & Leadership Department at West Point uses a simple, one-page form that provides such structure for evaluating junior officers assigned teaching duties within the department (shown in Figure 8.1). Note that the junior officer completes three columns of questions pertaining to duty performance (performing well?), professional growth (has a future?), and well-being (has a life?). This mentoring is completed quarterly, but it is not part of the officer’s formal annual evaluation (the Officer Effectiveness Report, or OER). We especially emphasize the last column because of the importance of family and nonwork goals and activities to overall well-being. Corporations and other organizations may easily adapt this form to fit their mission and values. The purpose of the form is to encourage self-reflection followed by meaningful dialogue with the mentor, who in this case would be a senior officer.

3. Mentoring must be genuine. Managers who go through the motions of mentoring simply because their own supervisor requires them to mentor their subordinates will fail. People can sense insincerity instantly. Leaders and managers throughout the organization’s hierarchy should be coached and trained in career-counseling skills, and their competence at this important aspect of leadership should be included in their own evaluations and feedback.

4. Do not confuse mentoring with performance evaluations. Mentoring is developmental in focus, not evaluative. Some aspects of performance may be discussed, but the focus is on what training and support the subordinate needs to improve, rather than on a performance rating that may impact pay or promotions.

5. Be honest. Most employees want to do well and will respond favorably when constructive feedback is included in mentoring sessions.

6. Identify the informal mentors in your organization. Encourage them and reward them for their efforts. These natural mentors often do the bulk of the mentoring in any organization, and effective leaders learn to leverage these contributions to complement formal mentoring strategies.

Figure 8.1

SKILL BUILDING

Character is not a fixed entity. Some aspects of temperament may be genetic, but character develops over time. Much of this occurs during childhood and adolescence. But character continues to evolve throughout adulthood. Moreover, this development—even among adults—is highly dependent on a person’s situation. Psychologist Richard Lerner describes character development as an interaction between the individual and the environment.3 According to this way of thinking, “good” character refers to behaviors, thoughts, and actions that are mutually beneficial to the individual and his or her social environment.

Psychologist Angela Duckworth agrees. She specifies three components to building character. These are mindset, expert practice, and a social and physical environment that provides opportunities to learn.4 Mindset, based on Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck’s research, is especially relevant.5 People with a fixed mindset believe that attributes such as intelligence or character cannot be changed. This discourages efforts to improve cognitive or character skills. In contrast, people with a growth mindset believe that these attributes can change, with effort and feedback. Moreover, Duckworth finds that a growth mindset increases grit, and higher grit strengthens the growth mindset, resulting in what she calls “a virtuous cycle.”

From an organizational perspective, this growth mindset view of character underscores the importance of a culture deeply steeped in positive values. When individuals enter a new organization—a school, team, or business—they come to that organization with character traits that are not set in stone. To attain mutually beneficial outcomes, the individual may adapt the behaviors, thoughts, and actions that make up their character to fit the organization’s stated values.

Looking at character as a malleable skill enables the organization to devise creative strategies for honing and developing character. Successful organizations think of a variety of ways to do this.

CHARACTER EDUCATION AND SELF-REFLECTION

Teaching people about character, giving them the opportunity to self-assess their own character, and leading discussions on how to use positive character to achieve personal and organizational goals are important. One example comes from the Military Child Education Coalition (MCEC), a nonprofit organization formed to advocate for the needs of military children. One of their programs is called Student 2 Student or S2S. In the S2S program, students, including children of both military and nonmilitary parents, can volunteer to form a S2S chapter in their school. Throughout the United States and in thirteen other countries, MCEC has trained more than a thousand elementary, middle, and high schools in S2S programs, helping thousands of children along the way. The S2S chapters offer social and emotional support to children who change schools frequently, often coping with one or sometimes both parents deployed in combat zones, and even dealing with the severe wounding or death of a parent from combat.

From these S2S chapters, about 120 teens ranging from high school freshmen to seniors are selected to attend MCEC’s National Training Seminar (NTS), held each summer in Washington, D.C. One of the programs available to them is a character-development workshop. Prior to attending, they complete the VIA-IS and bring their results to the NTS. The workshop begins with a general discussion of character and individual strengths, but quickly transitions into a hands-on education and reflection exercise. First, they are told to list their top six character strengths and to “reflect on how you have used one of your signature strengths to accomplish something difficult, to achieve a goal, or to overcome an obstacle.” Then they pair off and describe to their partner how they used the strength to address their personal challenge. The workshop facilitator then asks for volunteers to share their experiences with the group. In one session a sixteen-year-old high school student remarked, “My number one strength is humor, but it’s also my weakness because my sense of humor often gets me in trouble.” This is a terrific insight.

The students are then assigned to one of six groups corresponding to the character virtues of knowledge and wisdom, courage, humanity, justice, temperance, and transcendence. They are presented with a realistic scenario often faced by teens. For example:

You have just moved to a new school (your fourth such move). Your new school is in a town where most of the other students have grown up together and have formed close cliques and friendships, and you are finding it difficult to make real friends. You feel like an outsider and are now spending much of your spare time interacting with friends from your former school (which you liked very much and where you had many friends) on social media, and not enjoying fun times with new friends.

Think about the moral virtue your group has been assigned. Discuss among your group members how you could use individual strengths within your assigned virtue to begin making new friends and fitting in better in your new school. Be specific with recommendations and be prepared to share your ideas with the other groups.

The students discuss how they would do this. For instance, if assigned to the humanity virtue, they would talk about how to use the character strengths of kindness, capacity to love, and social intelligence to address the problem. The facilitator asks students at each table to lead a discussion on their chosen strategy. The students come up with highly innovative and inspiring ideas for leveraging character to address the problem. If time allows, they may be given a second but quite different scenario to consider, such as dealing with the death of a classmate.

The workshop concludes with a third exercise, in which the students are introduced to the ways of building character we are discussing here—positive and sustained mentoring, skill building, and opportunities to lead. They are asked to discuss how to better incorporate these principles in their own schools. Once again, their ideas are quite creative. In many cases, they take these ideas back to their schools and integrate them into existing S2S strategies.

These exercises are based on the notion that the twenty-four character strengths represent a toolbox, with individual strengths representing tools that are well matched to different sorts of jobs. The character strengths needed to excel academically differ from those needed to cope with the death of a loved one or the sadness and loneliness experienced when separated from a parent during his or her combat deployment.

CHARACTER-BUILDING TRAINING ACTIVITIES

The character traits of trust and leadership can be honed through field training exercises. The Thayer Leader Development Group, a private company located near West Point, provides leader- and character-development training for corporations. In addition to leadership education and reflection exercises on character similar to the ones used at the MCEC National Training Seminar, they have their clients complete a Leader Reaction Course (LRC). The LRC is a field exercise with a series of practical problems and obstacles that the group must overcome. Solutions require communication, mutual trust, and interdependence. A facilitator oversees the group’s efforts, then provides feedback to participants on what went well and what did not. This hands-on training provides a memorable way of learning about one’s character strengths and seeing how different team members may pool their strengths to complete a challenging task. Like the MCEC workshop, the goal is for participants to learn about their character and leadership styles, and to take those insights with them as they return to their parent organization. With a little research, you can probably locate a company that offers this kind of leader- and character-development training in or near your area.6

CHARACTER-BASED EXERCISES

Positive psychology provides a number of ways to build positive character strengths.7 One exercise involves completing the Values-in-Action Inventory of Strengths and listing your top five character strengths, called your signature strengths. Then you are instructed to intentionally and mindfully use one or more of your signature strengths over the next week in challenging situations. This exercise builds self-awareness of strengths and inculcates the idea that your character strengths are a tool, along with your intellectual ability, for you to respond effectively to problems. This is a vital skill for leaders as well as individuals.

Another positive psychology exercise is “hunting the good stuff.” In this exercise, you take a few moments at the end of each day to reflect on what went well. Then write down three or four things that went well, and include a short description of the event and why it went well. This reflective exercise builds the character strengths of perspective and gratitude, among others.

The gratitude visit is another powerful exercise. We described this earlier, in chapter 4. Reflecting on the beneficence of others and then overtly telling them about why their actions were so important is moving, with long-lasting positive effects on mood and outlook.

Besides building strengths, such exercises also pay a dividend of improved mood.8 In this sense they build resilience. Resilience training is common in many high-stress organizations, including the military and law enforcement. Corporations that include character-strength-building exercises in their employee-development training would reap the dual benefits of enhanced character and resilience. The US Army’s resilience program, Comprehensive Soldier Fitness (CSF), incorporates these and other training protocols to achieve this goal among hundreds of thousands of soldiers each year.9

YOUTH SPORTS

Participation in organized sports, especially among children and teens, provides an opportunity to develop and shape character traits. As General Douglas MacArthur famously said, “On the fields of friendly strife are sown the seeds that on other days, on other fields will bear the fruits of victory.”10 General MacArthur’s observation reflects the widely held belief that participation in sports not only strengthens the body but also strengthens character. At West Point this notion is so firmly entrenched that its football players prior to taking the field place their hands on a plaque reflecting the importance of sports in officer development. Attributed to General George C. Marshall, the quote on the plaque reads, “I want an officer for a secret and dangerous mission. I want a West Point football player.” Implicit in this demand is the notion that football prepares officers to be physically tough and to possess character strengths of grit, determination, and bravery.

While this may be true for West Point football players training to be Army officers, a fair question may be whether organized sports are linked to character development in children. Certainly, parents of the millions of children enrolled in youth sports believe this to be true. But what have psychologists learned about the nexus between youth sports and character development? More and more psychological research points to the value of participation in sports in positive youth development.

Dr. Andrea Ettekal, a professor at Texas A&M University, has addressed the issue of sports and positive youth development among military children. As we have discussed previously, military children face special challenges, including frequent moves. Ettekal’s research shows that participation in organized sports makes children feel that they matter, offers social support, presents opportunities to lead others, gives a feeling of belongingness, and builds self-efficacy.11 Her work shows that sports build both performance character (grit, self-regulation, etc.) and moral character (integrity, fairness, empathy, loyalty, etc.).

While Ettekal acknowledges that sports can result in negative outcomes such as stress or aggressive behavior, if done right, they promote positive youth development. Some elements of doing it right include positive competition versus a win-at-all-costs attitude, recruiting coaches who emphasize and explicitly teach character development through their sport, educating parents to help their children understand the character lessons that sports provide, and playing for the right reasons, including challenge and fun, and for physical and mental health.12

Engaging in sports for fun has been addressed by Dr. Amanda Visek of George Washington University. Visek and her colleagues brainstormed with children to learn what the components of fun were from the children’s perspective. The results are fascinating. On a cluster map, the researchers classified eighty-one determinates of fun into eleven more general fun factors. These eleven facets included positive coaching, team rituals, learning and improving, team friendships, and positive team dynamics.13 Fun as a transient positive emotion (elation or emotional high) was not a primary determinant of fun in sports. Rather, aspects of sports that addressed engagement or meaning and purpose (trying hard, learning and improving) were principal contributors to fun in sports. This is congruent with findings from positive psychology that show that engagement and a sense of meaning and purpose in life are more important determinants to life satisfaction than simple, hedonic pleasures.

Visek’s research also debunks several myths about sports participation in children. For example, winning was only ranked number forty out of the eighty-one determinants of fun. And smiling and goofing around are not reliable indicators of fun. Rather, children who appear focused and are developing their athletic skills are having more fun than those who joke around. Perhaps the most important debunked belief is the cultural notion that fun for girls lies in the social aspects of the game such as forming friendships, in contrast to boys, who are thought to derive fun from competition and skill development. Visek’s research shows that contrary to popular belief, what is most fun for young athletes does not vary much by their sex, age, or level at which they play. School administrators, coaches, and parents would benefit from learning more about Visek’s findings, and children would benefit if these findings were integrated into the design and management of youth sports.

Ettekal’s and Visek’s research is consistent with Duckworth’s view that mindset, expert practice, and a supporting environment are critical in building character. Sports can contribute to all three of these factors. It fosters a positive mindset by allowing children to learn firsthand that they can improve at difficult tasks. Sports allow children to build both physical and social skills through expert practice. Duckworth emphasizes that expert practice—sometimes called deliberate practice—is not “fun” in the usual sense of the word. Rather, it is fun in the ways that Visek finds in her research. Duckworth’s third component of character growth requires school administrators, coaches, and parents to craft a positive environment in which children may derive the positive benefits of sports.

Framing sports as an opportunity to build a growth mindset, to engage in challenging and difficult skill development, and to be part of a team with positive organizational values may begin to shape the type of character that General MacArthur and General Marshall had in mind when thinking about sports and character development in soldiers.14

FORMAL CURRICULA

The College Board recognizes the importance of character education as preparation for college and being a good citizen. Leaders of the College Board, known for administering the SAT, began considering which, of all the skills and knowledge they test, are most important for success in both college and life. Their answer, which may surprise you, is computer science and the US Constitution. So, the College Board updated and revamped their advanced placement courses that cover this material.15

Computer science may seem obvious, but why the US Constitution? According to Stefanie Sanford, chief of global policy and external relations for the College Board, appreciation for the role of character and citizenship in student success is increasing. With this in mind, the curriculum for the AP course in US Government and Politics must now include the study of passages from nine founding documents, including the Constitution, and of fifteen critical Supreme Court cases, each of which address one or more of the five freedoms included in the First Amendment—freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom of the press, freedom to assemble peaceably, and freedom to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

Sanford maintains that this in-depth study of the US Constitution builds character via direct knowledge of, and appreciation for, the moral virtue of justice. Specific strengths included in this moral virtue are citizenship, fairness, and leadership. By creating this AP curriculum, Sanford and her team at the College Board have created a systematic approach to enhancing the character strengths in young people that are needed for them to become productive students, leaders, and citizens.

LEADERSHIP OPPORTUNITIES

The third component of character building is providing leadership opportunities. In leading others, a person learns how his or her character influences others. In leading and influencing others, you must learn to use a variety of character strengths. Honesty, integrity, critical thinking, social intelligence, kindness, empathy, perspective, fairness, and a host of other character strengths are fundamental to effective leadership.

Early in life, in grades K–12, students are provided a variety of opportunities to lead and influence others. This may occur in the classroom, in school clubs, or in athletics. School-aged children may learn leadership through participating in extracurricular activities such as scouting. Many icons of leadership were involved in leadership activities at an early age.

West Point recognizes this through its admissions requirements. Prospective cadets are evaluated for academic potential through high school grades, class rank, and standardized test scores. Their physical potential is evaluated by their participation in sports and through a formal assessment of physical ability, called the Cadet Fitness Assessment. The third leg of the admissions triad is leadership potential. Applicants who have held leadership positions in clubs, have been the captain of a sports team, or have shown other evidence of leadership such as being an Eagle Scout are more likely to be admitted. West Point values these applicants because years of experience have demonstrated that such young people have not only honed leadership skills through practice, but they have also developed and sharpened their positive character traits.

Our advice for other organizations is to provide progressively more responsible leadership opportunities for their members. One S2S student pointed out that school leaders need to make sure that everyone is encouraged to pursue leadership opportunities, and not just the same kids over and over. We concur. Schools may develop a more focused approach to this, to ensure all students receive these opportunities. Corporations may find innovative ways to provide leadership opportunities to as many employees as possible. A promising nonmanagement-level employee may benefit from being assigned as team leader to tackle an important task. Systematically rotating short-term leader assignments will strengthen the workforce by sharpening leadership and attendant character strengths across more workers.

DEVELOPING LEADERS OF CHARACTER: THE WEST POINT LEADER DEVELOPMENT SYSTEM

In 1802 West Point began as a military training academy focused on basic engineering and soldier skills. In the twenty-first century it has become a comprehensive undergraduate institution with academic majors ranging from engineering, math, and science to the humanities and social sciences. As part of this evolution, West Point has come to emphasize aspects of character that go beyond the honor code and to reinforce its credo of Duty, Honor, Country.

Those who educate, train, and develop cadets understand the overriding importance of character in officer development. Over the past few years, West Point refined its leader development program to focus more directly on character. The desired character traits it seeks to cultivate in cadets span the breadth of the head, heart, and gut strengths discussed in this book.

Cadets coming to West Point are nominated by their congressional representative or senator, ensuring that future Army leaders represent all of America. The cadets come to West Point with a set of values developed from the communities they grew up in, values influenced by their home, their school, teams they played on, and other community institutions of which they were a part. West Point’s values are mentioned in its mission statement as duty, honor, and country, and its leader development program aims to internalize these values so that they are part of every graduate’s essence. Thus when graduates are faced with a potentially compromising situation, their natural response is based on these internalized values. The cup-of-coffee analogy mentioned earlier is what West Point expects its graduates to aspire to.

Cadets come to West Point from all walks of life, and while the academy hopes they enter with the values of duty, honor, and country, this is not always the case. To transform a cadet candidate into a graduate who is a leader of character, the West Point Leader Development System (WPLDS) was created so that cadets are immersed in it from the day they arrive until the day they graduate.

The WPLDS is designed to promote three important leader-of-character outcomes—to live honorably, lead honorably, and demonstrate excellence. To “live honorably,” a West Point graduate is expected to take morally and ethically appropriate actions regardless of personal consequences, exhibit empathy and respect toward all individuals, and act with the proper decorum in all environments. To “lead honorably,” a West Point graduate is expected to anticipate and solve complex problems, influence others to accomplish the mission in accordance with Army values, include and develop others, and enforce standards. To “demonstrate excellence,” a West Point graduate is expected to pursue intellectual, military, and physical expertise, make sound and timely decisions, communicate and interact with others effectively, and seek and reflect on feedback.16

To develop each cadet into a leader, four formal programs each focus on character growth. The first program focuses on the cadet’s intellectual development within the academic program. Each year, West Point enjoys top rankings among public colleges across the country. In 2017, Forbes ranked it the number one public college, and in 2016, US News & World Report ranked it number two. West Point’s academic program is guided by the Thayer method of instruction, where cadets are responsible for their own learning and lecturing is rare. In a classroom that is more like a seminar where faculty members are facilitators, the unique learning experience enables the development of intellectual agility, adaptability, and thought diversity. Each year, twenty-five to thirty cadets are awarded nationally competitive scholarships (Rhodes, Draper, Marshall, Fulbright, East-West, and Lincoln Labs, among others).

In their four years at West Point, cadets complete three academic courses that specifically address leadership theory and practice. All plebes complete a course titled General Psychology for Leaders. The course covers the same topics included in psychology courses at any university, but frames the concepts in relevance to leadership. The course is taken during the plebe year because cadets can build on this knowledge outside the classroom as they are given greater and more diverse leadership opportunities at West Point. In the junior (cow) year, all cadets enroll in a course called Military Leadership. This course covers theories and good practices of leadership. During summer training following the junior year, cadets serve as leaders during field training exercises, giving them the opportunity to apply what they learned in both the plebe- and junior-level courses. Finally, during the senior year, cadets complete a course entitled Officership. This course, taught by combat-seasoned Army officers, synthesizes what cadets have learned their first three years at West Point about leadership, both from the classroom and in the field. Altogether, these academic experiences prepare cadets to be effective Army leaders.

The second WPLDS program is in the cadet’s military development. Most of the military training occurs in the summer and includes everything from rifle marksmanship to land navigation, and practice leading a twenty-to-thirty-person platoon in the active Army for a month or more. The first summer is cadet basic training, a program designed to transition a civilian into a cadet. Its purpose is to teach basic cadet military skills, and to teach one of the most fundamental lessons of leadership: how to be a good follower and team member. The second summer expands the cadet’s individual and collective military training and offers the opportunity to attend a military school, such as Airborne training at Fort Benning, Georgia, or Mountain Training at Fort Greely, Alaska. The third summer places cadets in leadership positions over other cadets who are executing their freshman and sophomore military training. In these positions, cadets practice leadership, succeed and fail, receive feedback, and grow as a result. During the final summer, some cadets are placed in senior cadet leadership positions, and each cadet also travels to an active-duty Army post to assist with the leadership of an operational Army platoon. This enables cadets to experience firsthand what they’ll be doing as a newly commissioned officer in the Army, after graduation. Cadets also take military-science courses during the academic year. These are designed to augment the summer military training and to enable cadets to study and reflect on previous experiences and training. In these classes, they learn from the combat experiences of their instructors.

The third WPLDS component is the physical program, which includes academic courses (survival swimming, boxing, military movement), annual physical tests (both the Army’s Physical Fitness Test as well as West Point’s challenging Indoor Obstacle Course Test), and participation in a team sport at the intramural, club, or intercollegiate level. Many leadership lessons are to be learned in a tough physical program. After Douglas MacArthur’s World War I experience, he felt that physical acumen was essential to effective leadership. When he became the West Point superintendent in 1919, he coined the phrase “Every cadet an athlete.” The physical program is designed to instill cadets with the character strengths of grit, determination, and confidence.

Leading the nation’s sons and daughters in the most challenging circumstances requires officers who lead from the front and who share hardships. The physical program is designed to create those challenging circumstances so that cadets will develop the physical skills, confidence, and grit necessary to lead within this crucible experience. For example, boxing teaches a combat skill and also enables cadets to come face-to-face with fear and overcome it. The physical program nurtures the development of tenacity, resilience, grit, discipline, and perseverance.

The fourth component of WPLDS is the character-development program. Character development occurs within a culture that embraces a character ethic, which is a set of principles defined by its values and standards of behavior. Fundamental to this ethic is the Cadet Honor Code, which states, “A cadet will not lie, cheat, or steal or tolerate those who do.” The ethic goes much further than not lying, cheating, or stealing. It also includes “honorable living,” which is the internalization of both cadet and Army values, so that they become part of a soldier’s essence. Living honorably is not something that only cadets aspire to; it also defines the behavior of the entire community, including instructors, staff, faculty, and anyone who engages with cadets. “All members of the community are expected to model both character and leadership, and by living and working within this community of models, character and leadership are built, reinforced, and refined.”17

Going back to the Cadet Honor Code, it is important to highlight the “no tolerance clause” because that is what sets this code apart from other honor codes. Since trust is a function of character and competence, character defects among military leaders, especially senior military leaders, erode the trust between the nation and its military. To maintain the high standards that leaders of character require, the profession of arms must hold itself accountable. The profession must not forfeit this to someone else, and therefore each soldier must take full responsibility to hold him- or herself and others accountable. In this way, “nontoleration” becomes a critical component to the responsibilities leaders of character have within the profession of arms.

The “Cadet Creed” articulates these values. New cadets are required to memorize this creed during their first summer at West Point. Additional references to character and values are found in the “Cadet Alma Mater” and “The Corps,” a poem that emphasizes this same set of values.18

CADET CREED

As a future officer,

I am committed to the values of Duty, Honor, Country

I am an aspiring member of the Army profession, dedicated

To serve and earn the trust of the American People.

It is my duty to maintain the honor of the Corps.

I will live above the common level of life, and have the

Courage to choose the harder right over the easier wrong.

I will live with honor and integrity, scorn injustice,

And always confront substandard behavior.

I will persevere through adversity and recover from failure.

I will embrace the warrior Ethos, and pursue excellence

In everything I do.

I am a future officer and member of the Long Gray Line.

Self-reflectional feedback is critical to a cadet’s character development. What does my action (behavior or performance) say about me as a developing officer? What have I learned about officership and leadership? What have my experiences revealed about my strengths and weaknesses? And what do I need to do in the future to further my development? Every day at West Point provides opportunities for cadets to receive feedback. These lessons are reinforced by mentors who help the cadets understand their experiences.

Several programs are designed to encourage behavioral change so that cadet behavior becomes consistent with the values of duty, honor, and country. One program, called Leader Challenge, brings West Point graduates with combat experience back to the academy to meet with cadets in small groups, and to discuss in detail some of the ethical issues they faced on the battlefield.

The cadets also participate in small-group discussions on honor, respect, and sexual relations (designed to address sexual harassment and assault issues). The key to these dialogues is to create introspection and reflection. These sessions allow open and honest dialogue, with a peer facilitator. This becomes the engine that drives behavioral change.

Cadets sometimes make mistakes stemming from character failures. This must be addressed, both to hold cadets accountable, and to provide an opportunity for cadets to learn and grow. To facilitate growth in these situations, cadets may find themselves in a Special Leader Development Program. This intensive, reflective one-on-one program with a mentor includes projects, research, and instruction. Key to its success is the mentor-led reflection component, which drives an open, candid, and honest appreciation of the cadet’s motives and behavior, and how these relate to their performance within the profession. Most cadets who complete this program are stronger in character than most of their peers, including those who never had a character issue in the first place.

Not only is the West Point Leader Development System designed to develop a cadet’s intellectual, military, physical, and character skills, but it is also designed to develop the cadet’s leadership abilities, first as a follower and then as a leader. In everything cadets do, they find themselves living, engaging, leading, following, and studying within a military organization that includes both cadet leaders and followers. Cadets are assigned to numerous leadership positions within the organization, and by executing their duties, they learn the trials and rewards of both followership and leadership.

THE MAGIC OF THE WEST POINT LEADER DEVELOPMENT SYSTEM

The West Point Leader Development System works because it includes all three components of character development. From the day new cadets arrive at West Point to when they graduate and are commissioned as second lieutenants in the Army, they are given constant mentoring. A notable feature of WPLDS is that the responsibility to mentor and develop cadets belongs to every single person at West Point who has contact with them. Military trainers and professors are obvious examples. Each cadet also has a sponsor, often a staff or a faculty member, who opens his or her home to the cadet during the cadet’s entire West Point experience. Sponsors provide cadets a place to relax, get away from the daily grind, enjoy a meal at a family table rather than the mess hall, or to wash their clothes. Along the way, the sponsor models the values and character strengths needed to be an Army officer. Clubs and sports teams offer mentors as well.

West Point’s skill-building curricula are integrated with hands-on leadership opportunities in military training, sports, and other activities. Plebes study General Psychology for Leaders and are able to practice what they learn in their daily lives at West Point. Juniors take the leadership lessons learned in Military Leadership to the field the following summer, where they can discover what works or does not work for them. This coordination between classroom learning and hands-on learning is what makes WPLDS effective.

The third piece of character development—opportunity to lead—is emphasized throughout a cadet’s time at West Point. In their plebe year, cadets learn to be good followers. During their second year, every cadet serves as a team leader, responsible for the development of his or her own plebe. During the third and fourth years at West Point, cadets serve in a variety of leadership positions at progressively more responsible levels. Positions are rotated so that all cadets have the experience of being a leader. These positions include commanding a company, regiment, or the Corps, or serving as first sergeant during the regular academic year. Summer field training provides a myriad of other leadership opportunities. Throw in clubs and intercollegiate and intramural sports, and every cadet will have had multiple opportunities to develop leadership skills and character by the time the cadet receives an Army commission.

WHAT CAN YOU LEARN FROM THE WEST POINT LEADER DEVELOPMENT SYSTEM?

Your organization may not have the resources to fully implement a West Point Leader Development System type of approach to leader and character development. But leadership and character are critically important to all organizations, large or small, civilian or military, public service or for-profit. Corporations, schools, and other organizations may use WPLDS as a model for how to approach the three elements of character development. Although it may be done differently from West Point, a culture of mentorship can be nurtured in any organization. Similarly, organizations may adopt a variety of strategies for educating their members about character and its relationship with leadership. Finally, organizations may devise ways to increase leadership opportunities at all levels within the organization.

Taken as a whole, WPLDS and the other examples of leader and character development we have presented may serve as a blueprint for building high-character organizations. By taking the seeds you have so carefully selected (good people), planted in fertile ground (a value-driven culture), and carefully cultivated (nurtured in character), you will enjoy a bountiful harvest through increased organizational effectiveness that is sustainable.